Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a Germanic collective people who gradually settled and increasingly ruled Great Britain from the 5th century onwards. From the middle of the 6th century, the Anglo-Saxon culture was already dominant on the island, as the Roman - Celtic population had either been displaced or assimilated. The Anglo-Saxon period is considered to be the time in British history from around 450 to 1066, when the Normans finally conquered the country.

The gathering people of the Anglo-Saxons consisted mainly of Saxons and Angles . These tribes appear as an association with groups consisting of Jutes , Frisians and Lower Franconians from the 5th century onwards. The ethnic origin ( ethnogenesis ) of the Anglo-Saxons was the result of a long process of immigration and the admission of parts of the Celtic-Romanic pre-population of Britain .

An Anglo-Saxon culture initially developed from this association of peoples. Later, supplemented by Scandinavians , Danes and Francophone Normans in the 11th century , a cultural-ethnic constellation formed over the course of time and these developments in the High Middle Ages , which was later interpreted as the English nation and culture. Anglo-Saxon has its essential linguistic roots in the Old Saxon language. Even today, despite 1500 years of different development, there are many similarities between the English and Lower Saxony languages .

The term is often figuratively in terms of the inhabitants of the day British Isles and the English-speaking peoples in North America and Oceania applied (Americans, Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders).

Origin of the Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons are essentially the descendants of two continental Germanic tribes: the Angles were mentioned in writing as Anglii (Kaiserγγειλοι) by Tacitus AD in 98 AD and later by Claudius Ptolemy (2nd century) as Angeiloi (Ἄγγειλοι) and probably settled there North-east of what is now the state of Schleswig-Holstein , where the fishing landscape still exists today . The fishing rods are listed together with other tribes by Tacitus in his description of the historical-geographical conditions of Northern Germany. Tribes that can be localized on the Danish islands, on the Baltic Sea coast and on the lower Elbe and together formed a northern political-cultic group in the Suebi association , with Ptolemy as Suēboi Angeiloi (Συήβοι Ἄγγειλοι).

The ancient Saxons are not to be confused with the later Saxons of the High Middle Ages and the inhabitants of today's state of Saxony . Rather, it is about the forerunners of the later tribal duchy of Saxony (Old Saxony), which was settled in the area of today's Lower Saxony as well as in Holstein , Westphalia and Ostfalen . The old Saxons at the beginning of the migration period were linguistically and in their material culture much more closely related to the Frisians. Tacitus does not mention the Saxons in his Germania , but he lists the tribe of the Chauken , who settled on the Lower Elbe North Sea coast and which Pliny the Elder also knows, while Ptolemy the actual Saxons ( Saxones, Greek Σάξονες) “... in the neck of the Cimbrian Peninsula ”(probably today's Holstein). In the 3rd century the two peoples were united to form the now larger tribal union of the Saxons. The change accelerated with the unification to the large Saxon tribal and people's association with the assimilation of small tribes and remnants of former important tribes, such as the Cherusci in the 3rd / 4th. Century. The Saxon groups, which later formed part of the Anglo-Saxons, separated by moving to Britain even before the formation of the large people of the early medieval Saxons.

Angling and Saxons were probably closely related, as they belonged to or came from the same continental Germanic cult group of the Ingwäons , despite existing cultural differences such as among other things in the funeral rites. The exact course of Anglo-Saxon ethnogenesis is the subject of lively scientific discussion , as with all gentes of the late ancient migration period . This also applies to the question of how and whether material culture and ethnicity are related.

At that time the tribal groups of the Jutes belonged to the West Germanic tribes in terms of language and cult. Today's Jutes, in Danish Jyder , are, however, of North Germanic origin and should not be confused with these Jutes . The Frisians have been well involved in their ancestral homeland only with small groups in the formation of the Anglo-Saxons. Research on place names in particular has established the settlement areas of these Frisian settler groups. The late antique historian Prokop (6th century) mentions the Frisians in his work on Justinian's Gothic Wars and calls them Φρίσσονες ( Frissones ).

A Franconian share is only suspected, among other things on the basis of uncertain derivations of place names and the analysis of old English literature and the evidence attached to it - such as in the Beowulf epic. These Frankish settlers probably only came to the British island with the last wave of immigration towards the end of the 5th century.

The name

The origin and the development towards the formation of the name Anglo-Saxons is no longer traceable today; Nevertheless, the available sources allow conclusions to be drawn that make the assumptions derived from them plausible. Basically, among the colonists, especially among the Jutes and Angles, the ties to their continental relatives seem to have been loosened quite quickly - up to and including termination.

Beda Venerabilis (d. 735), an important Anglo-Saxon scholar, localized the Jutes after the migration in Kent and gave them back in the form of the name Iutae , which does not come from native Old English tradition. The old English form would be * Eotas (cf. Eotenas , attested in Beowulf , lines 1068-1159), but this has nowhere been passed down. So Beda no longer knew the correct name. Around 700, only faint memories of the name and the associated “original home” may have existed. Alfred the Great then gave Iutae with Gēatas , the name of the Gauts from Sweden , in his translation of Beda's church history .

The common Old English form Ongle for Angle represented Alfred with the name of the landscape, Angel, instead of the correct form Angli . He also no longer knew the names of the old tribes himself.

The Saxons in Britain, on the other hand, kept contacts with the mainland in connection with the dominant continental expansion of the tribal union. To distinguish the English branch, the Saxons of the island called them Eald-seaxan , Old Saxons.

It was no longer clear to Beda that Angles and Saxons were different tribes. He referred to them as Angli sive (vel) Saxones , as if they were one and the same under different names. Alfred corrected Beda with an ond or an "or". Beda's basis for his representations and assumptions may have been traditional sayings and symbols in the form of the allotted rhyme .

" Of Englum ond Eotum (Iutum) ond of Ealdseaxum "

"The Anglo-Saxons come from the Angles and the Jutes and the Old Saxons"

This type of triad fits the old pattern of Germanic ancestry legends such as the family tree of Mann in Tacitus Germania, Chapter 2.

The name of the Angles eventually dominated that of the Saxons as a unified name for all Germanic tribes on the British Isles, perhaps to better distinguish them from the continental Saxons (because those Angles that had not moved to Britain had been assimilated by other tribes, so none There was a risk of confusion). The Anglo-Saxon kings called themselves rex Anglorum , or rex Anglorum Saxonum . Pope Gregory I named the King Æthelberht of Kent - himself of Jut origin - in a letter from 601 rex Anglorum . Around 1000, the term for country and people, Englar and Englaland , which was introduced by the Norse and the Vikings , replaced the older indigenous names such as Āngelþeod (“fishing people”). This new form appears in both the Old Norse and Anglo-Saxon texts and ultimately led to the emergence of the short form England .

The Romanized Celts, on the other hand, named the invading Teutons after the Saxons, Kymrian Sais ("English") for the people and saesneg for the language. The Latin scribes of the continent also initially used the terms Saxones and lingua Saxonica .

A main reason for the establishment of the fishing name may have been a political and cultural preponderance of fishing rods in the first few centuries. In order to avoid misunderstandings, the term Anglo-Saxons was formed very early on by external perception - not yet directly and clearly with Beda, with Paulus Diaconus around 775 Angli Saxones in the meaning of "the English Saxons" in order to differentiate between the to represent mainland Saxony. Ultimately, the formation of the name Anglo-Saxons is a product of several confluent factors: On the one hand, it is a learned Latin form, then a result of the loss of the ancestral continental roots, and finally, the forgetting of the originally clear tribal identity and the external perception still play a part in it.

Beginnings up to the settlement of the British Isles

The first military invasions of Saxon groups into Roman Britain can be shown to have taken place in the second half of the 3rd century. Saxon followers (in addition to Franconian groups) on the raid and pirates landed on both sides of the Channel coast (see also Saxon coast ). Incursions by Iro-Scottish tribes forced the Roman military administration to reform the military infrastructure, defense and fortification systems. According to many researchers, this led, among other things, to the transfer of command and strategic responsibilities to Saxon leaders; They therefore served as federates under the comes litoris Saxonici (commander of the Saxon coast) . The conclusion is that Germanic defenders in Roman service and their families have settled in southern Great Britain at least since the late 4th century, i.e. before the actual mainstream of Germanic colonization, or conquest, from the middle of the 5th century. These settled south along the Thames in what is now greater London, in Essex, Kent and were stationed on the east coast. Other researchers, on the other hand, assume that the "Saxon coast" served to repel Saxon attacks and was therefore not occupied by Saxon foederati , but also assume that the first Saxon mercenaries served in Britain as early as the late 4th century.

Escalating civil wars in the Western Roman Empire and the temporary collapse of the Roman Rhine border in 406/407 AD due to the crossing of the Rhine by some Germanic warrior groups led to Emperor Honorius (ruled 395-423) and the usurper Constantine III. (ruled 407–411) to withdraw most of the regular Roman troops from Britain around the year 407. Although Honorius did not give up Britain, he was forced to leave the island largely to itself. The resulting power vacuum and the unregulated political conditions offered ideal space and opportunities for immigration from the mainland.

From the beginning of the 5th century, there was evidently an increasing number of people moving to the British Isles from the North German-Lower Rhine Plain, which increased over time and developed into the main stream of emigration to Britain from around 450 onwards, although the extent of immigration is controversial . However, there are also sources for the events in Britain for the period from the early 5th century to around 600. The most likely scenario (following the Gildas report ) is that the Roman-Celtic civilian population of the island recruited Anglo-Saxon foederati on their own after the withdrawal of the imperial troops to defend their country against Picts and Scots . Perhaps the "tyrant" Vortigern played a role in this; according to later tradition , he is said to have called two (probably not historical) Saxon leaders named Hengest and Horsa ('stallion' and 'horse') into the country. Around 440 there seems to have been a revolt of the Saxon mercenaries, who subsequently received further influx from the continent and slowly pushed the Romano-Celts back.

The British had lived under Roman cultural influence for a very long time and gradually became Christians in the 4th century. They were probably not Romanized to the same extent as the Gallic Celts, and there were also great social and geographical differences in the acceptance of the Latin language and civilization in Britain. Most of the Angles and Saxons came from areas that had hardly been touched by Roman civilization. The British were therefore Romanic foreign peoples for these landing warriors (Old English Wealh , nhd. Welsch - hence the name of Wales ). For many Christian Romano-British, the predominantly pagan Anglo-Saxons were barbarians . There was a partial displacement by the advancing Anglo-Saxons, but also a voluntary retreat of the Celtic population in the southeast.

Around 500 the Romano-British, led by Ambrosius Aurelianus, were able to stop the advance of the attackers for a few decades (perhaps an origin of the Arthurian legend ), but this was only a respite. Some of them moved to Brittany or withdrew to the heights and earth fortifications ( Wansdyke , Bokerly Dyke ). Parts of the British were enslaved (ags. Wealas ), a large number also seem to have defected and adopted the customs and language of the invaders. It is also said to have come to bloodbaths among the Roman-British urban population (among other things in Chester in the year 491), although according to more recent findings there was probably no mass expulsion of the Romano-British. There were also military setbacks for the Germanic conquerors, for example in the battle of Mons Badonicus (which cannot be precisely dated or localized) around 500; then, according to Gildas, the further Anglo-Saxon land grabbing stopped initially. After the decisive battle of Deorham in 577, the territories of the Cornish and Welsh Celts were split up by the invading Anglo-Saxons. In cities like London , York and Lincoln , part of the Romano-Celtic population remained settled, as the Anglo-Saxons apparently avoided these places at first. The places were later evacuated by the British, but the Roman villas were hardly used by the Germanic tribes who advanced.

In the 8th century Mercia made a name for itself as a supreme power, King Offa of Mercia is considered by some to be the first king of England. Mercian supremacy, however, was broken in the early 9th century by Wessex , which rose to become the most powerful Anglo-Saxon empire under Egbert von Wessex .

Settlement history in England

The Germanic tribes initially settled in a closed area, the nucleus of which was presumably assigned to them as foederati as part of their recruitment . According to linguistic (including place name research) and archaeological findings, after the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon revolt, only a small remainder of the Romano-Celtic population remained resident (other researchers explain the disappearance of Roman-Celtic graves with the fact that the previous population assimilated quickly). The Thames, the Humber , the Wash and along the old Roman road the Icknield-Way are considered gateways . At the beginning of the 6th century, the Germanic-controlled area of the southeast was bounded by the present-day counties of Hampshire , eastern Berkshire , southern Buckinghamshire , north-eastern Bedfordshire and Huntingdonshire . To the west of this line was Celtic-settled land, and the further expansion of the Anglo-Saxon sphere of power to those western and subsequently to other areas then included the Celtic population in the developing Germanic states or Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Basically, the extent of Anglo-Saxon immigration into Britain is unclear, especially since the interpretation of the archaeological findings, as mentioned, is controversial. In recent times it has even been doubted that the English language can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxons: Rather, it was only the Vikings (see below) who came to the island in such large numbers that Germanic dialects prevailed. What is certain is that Latin inscriptions were still being used in Britain in the 6th century .

Anglo-Saxon tribes

After Bede the gentes settled ethnically separated. The anglers settled primarily north of the Thames in East Anglia , the area of the middle fishing , Mercia and on the east coast to south of Edinburgh . The Saxons founded Essex , Wessex and Sussex in the Thames valley and south to the English Channel . The Jutes settled mainly in Kent and on the Isle of Wight . This strict ethnic division is, however, controversial, as one must rather assume an ethnically mixed settlement or conquest under the leadership of followers and this corresponds more to Germanic customs and procedures.

Settlement systems and forms

As on the Rhine, the newcomers apparently rarely adopted the Roman forms of settlement. Due to the circumstances described above, the Germanic tribes in their areas were dependent on a more mobile way of settling in settlements of the hamlet type. In these settlements, the type and number of mine houses and hall houses dominated . Most of the pit houses were probably used as storage rooms or weaving houses and less often as living space. The Mucking site in Essex was one of the largest settlements of the 4th to 5th centuries with 200 pit houses and 30 hall houses. The “mobile” layout of the buildings is particularly evident in the fact that the more representative hall houses erected as post structures are not comparable in size with the continental Saxon-Lower Germanic residential stable houses . These initial settlements, some of which later acquired an urban character, were often laid out next to old, destroyed and deserted Roman cities.

Agriculture was practiced in the same way as on the continent; archaeological evidence has shown the cultivation of barley , oats and flax as well as woad as a raw material for dyeing linen and other clothing materials. Livestock farming included pigs, sheep and cattle as well as horses, goats and domestic chickens. Cats and dogs were kept as additional pets. The field work was done with single-blade plows, harvesting was done with sickles, hips and scythes.

Numerous ceramics have been found from the 5th century that are rich in ornamental decorations, but were made without the use of a potter's wheel. The hump ceramic standing on a stand is important here . This form was particularly widespread in the Midlands and the Thames area and is usually assigned to the Saxons. Assigning the differing regionally restricted ceramic forms to the respective sub-peoples such as the Angles and Jutes and their settlement areas is only possible to a limited extent. However, there is evidence of a lively exchange and close relationships with the mainland on the basis of the vessel shapes in eastern England and from the Elbe-Weser area of the 5th century. Anglic forms, however, can be found in northeastern England.

The regional differences that can be seen in the ceramics are continued in clothing and handicraft jewelry, especially the distinct stylization of clothing as traditional costume through the different uses and numbers of brooches used . In the northern Anglic area a "three-fibula-costume" was worn, compared to a "two-fibula-costume" in the southern Saxon settlement area. The border derived from this, the so-called Anglo-Saxon-Line , which roughly divided between Angling and Saxony, is only to be set after the phases of the conquest of land. Only the later controlled capture of the lands led to a clearly recognizable separation between the predominantly Saxon or Anglic regions.

The dead were buried unburned in their costumes in the Saxon region and on the mainland. In the Anglic settlements and also in Wessex the cremation of the dead was partially carried out, and in Kent the dead were buried in barrows.

Social and state hierarchy

Nobility and clergy as well as free peasants with their own land belonged to the free ( Ceoris ), indigenous (Celtic-Romanic) British, lower peasants and servants to the unfree ( Theows ; cf. Old High German: thionōn , "serve"). High nobility and clergy formed the Council of Wise Men ( Witenagemot ). This elected the king, who was the political and military head. Usually the royal dignity was passed on to the firstborn son. The king passed laws, settled legal disputes and levied taxes. The members of the royal retinue ( Gesith from Old English sīþ , "journey") consisted of nobles ( Thegn / Thane ) who owned at least 240 hectares of land. In the event of war, they had to raise militias ( Fyrd ) for the king for one to two months a year . In addition, the king had his own army ( huscarls ).

The Anglo-Saxon state structure was administratively divided into Shires , headed by an Ealdorman from the high nobility, the highest administrative officer of a Shire was the sheriff .

Viking age

At the beginning of the 9th century the violent incursions and raids of the Vikings increased, the era of the Viking Age began in the Anglo-Saxon empires. First of all, the Anglo-Saxons achieved some defensive successes before the intensity of the attacks increased. The consequences of the great Viking invasion of 866 ( Great Pagan Army ) were particularly devastating . In the north of England the Danes established themselves in the Danelag . The Anglo-Saxon language was therefore also influenced by Danish.

Alfred the Great was able to repel the Vikings in 878 and unite large parts of Anglo-Saxon England, but the Viking threat persisted in the period that followed. Nevertheless, Alfred's reign represents a high point in Anglo-Saxon history, in which there was also a cultural redevelopment. The following Anglo-Saxon kings of England had to deal with external threats and internal conflicts again. In the early 11th century, Canute the Great ruled a North Sea empire to which England also belonged, although Knut's empire fell apart again with his death. In 1066 the Anglo-Saxon area was conquered by the Normans . Nonetheless, Anglo-Saxon culture and language persisted for a long time until they were mixed with the French language of the Normans. An example of the dispute between Anglo-Saxons and Normans is the mythical figure Robin Hood , who symbolized the resistance of the Anglo-Saxons against the Norman rule.

Anglo-Saxon culture

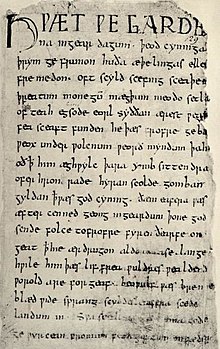

The cultural question of the Anglo-Saxons is inextricably linked with the emergence of early Christian England. Due to the primacy of Christianity, the state organization based on the Roman model was adopted by the nobility, as was previously the case with the Merovingian Franks; an important and not to be underestimated building block for the small Anglo-Saxon kingdoms . The flourishing clerical literature (the comprehensive works of the learned clergyman Beda Venerabilis are particularly noteworthy for the 8th century ), the mission, which also always had state-political touches and therefore sometimes had symbiotic features, marks the end of the pagan Anglo-Saxon period of settlement and consolidation accompanies and promotes the formation of what has been identified and understood as English.

If the culture of the first Germanic emigrants to the federates was indistinguishable from the continental tribal members, the consolidation of the 6th – 7th centuries was just beginning. Century, in harmony with the Iro-Celtic Christian mission, the steps of cultural alienation towards an independent Christian culture of Germanic character. At the same time, when the island fishing and Saxons broke new ground, the continental relatives remained in their traditional and accustomed cult. The resulting alienation was the natural consequence. The ceramic finds of the 6th century make it clear how people changed with the shape, especially the changing ornamentation up to the loss of all decorations in finds in Kent. The sacred architecture and design, the pictorial representations shaped and shaped the ideas and the sense of the people for the mastery of the new Christian form with the unmistakable Germanic heritage. In addition, there is the strong monastic influence from the monasteries on the everyday culture of the rural population, for example in the qualitative improvement of agricultural cultivation techniques.

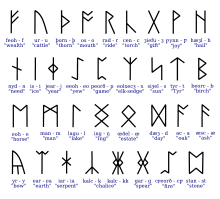

Language and writing

New English belongs to the Anglo-Frisian branch of the West Germanic language group . The three main ethnic parts of the Anglo-Saxons are linguistically closely related because they belonged to or came from the continental Germanic Ingvaeonian cult group.

Old English , which is similar to Old Saxon , therefore represents an essential root of the English language. Even today, despite 1500 years of different development, similarities can be seen between English and Low German , which developed from Old Saxon.

Religious Confessions

Pagan religion

The pagan period of the Teutons in Britain lasted about 150 years (considered from the middle of the 5th century). In essence, the first settlers continued their usual religious rite as in the old homeland. According to place-name research, the same main deities were worshiped as were enumerated for the continental Saxons (Lower Germanic tribes) in the Saxon baptismal vows of the Carolingian period; Tíw , Þunor and Wóden . The cult and worship of mother goddesses, comparable to the matrons of the Roman Lower Rhine region, was also practiced. Cultic-magical places such as springs, striking stones / rocks and trees were used for public and private sacrificial rites and places with former Celtic use were taken over. In connection with the religious-cultic rite are also the ideas of demons / belief in spirits, beings of lower mythology such as fairies, giants and others. Fragments or only sparse references from later Christian poetry allow conclusions to be drawn about local pagan ideas.

Mythical legends as such have not survived, apart from the epic Beowulf , and, if they existed, have been lost. Only the legend of ancestry (see Origo gentis ) of the Anglo-Saxons is preserved through Beda. He reports that the Saxons were called by the British King Vortigern and landed on the coast of Britain with three ships under the mythical brothers Hengest and Horsa . This type of legend of origin is also widespread among the Goths or Lombards , Tacitus reported in the Germania (Chapter 2) of the mythical descent of the Germanic peoples.

Christianization

Christianization began around 597 with the sending of 40 missionaries by Pope Gregory the Great and the expansion or reorganization of the English church by Archbishop Theodor of Canterbury , which - in contrast to the mainland - was largely completed at the end of the 7th century. It actually marks the end of the Anglo-Saxon phase in terms of continental and pagan origins in connection with the emergence of early English society or an incipient English identity. By far the most important source in this regard is Beda's extensive Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum . The Anglo-Saxons had previously formed several kingdoms ( heptarchy ). The turn to Christianity, like other places in the Germanic cultural area, was and always a question of the power-political opportunity of the ruling Anglo-Saxon aristocratic class. Popularly, the pagan customs and traditions were and were tolerated by clerical side and partly on the perceived compatibility in church worship adopted . As everywhere in the Germanic context, former pagan cult places were also converted into Christian ones through the establishment of chapels and the organizational establishment of parishes around these places.

See also

literature

- Michael Lapidge, John Blair, Simon Keynes, Donald Scragg (Eds.): The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester 2014.

- James Campbell (Ed.): The Anglo-Saxons . Penguin, London a. a. 1991 (orig. 1982).

- Peter Hunter Blair: An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-53777-3 .

- Nicholas Brooks : Anglo-Saxon myths. State and church, 400-1066 . Hambledon Press, London et al. 2000, ISBN 1-85285-154-6 .

- Sam Lucy: Anglo-Saxon Way of Death, Burial Rites in Early England . Stroud, Sutton 2000.

- Torsten Capelle : Archeology of the Anglo-Saxons - independence and continental ties from the 5th to the 9th century . WBG, Darmstadt 1990, ISBN 3-534-10049-2 .

- Cristian Capelli: A Y-Chromosome Census of the British Isles . In: Current Biology . No. 13 . Elsevier Science Ltd., 2003.

- Heinrich Härke: The origin of the Anglo-Saxons . In: Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer (Hrsg.): Classical Antiquities - Classical Studies - Cultural Studies: Income and perspectives after 40 years Real Lexicon of Germanic Classical Studies. De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-027360-1 , pp. 429–458 ( supplementary volumes to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde , vol. 77).

- Nicholas J. Higham, Martin J. Ryan: The Anglo-Saxon World. Yale University Press, New Haven 2013.

- Harald Kleinschmidt: The Anglo-Saxons . Beck, Munich 2011.

- Bruno Krüger (ed.): The Germanic peoples. History and culture of the Germanic tribes in Central Europe. Manual in 2 volumes . 4th edition. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1983. ( Publications of the Central Institute for Ancient History and Archeology of the Academy of Sciences of the GDR , Vol. 4).

- Henrietta Leyser: A Short History of the Anglo-Saxons. IB Tauris, London / New York 2017.

- Mark G. Thomas, Michael PH Stumpf, Heinrich Härke: Evidence for an Apartheid-like Social Structure in Early Anglo-Saxon England . In: Proceedings of the Royal Society B . 2006 ( online ).

- Rudolf Much, Herbert Jankuhn , Wolfgang Lange: The Germania of Tacitus . Carl Winter, Heidelberg 1967.

- Ernst Alfred Philippson: Germanic paganism among the Anglo-Saxons (Cologne Anglistic Works Vol. 4) . Publishing house Bernh. Tauchnitz, Leipzig 1929.

- Jürgen Udolph: The conquest of England by Germanic tribes in the light of place names . In: Edith Marold , Christiane Zimmermann (Ed.): Northwest Germanic. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1995, ISBN 3-11-014818-8 , pp. 223-270 (supplementary volumes to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 13).

Web links

- Comprehensive bibliography (PDF; 6.0 MB)

- Angling and Saxons as the elite ruling class - What the genes of today's English say about the structure of society in the early Middle Ages

Remarks

- ^ A b Nicholas J. Higham and Martin J. Ryan, The Anglo-Saxon World , Yale University Press, 2013.

- ^ Mark G. Thomas, Michael PH Stumpf and Heinrich Härke, "Evidence for an apartheid-like social structure in early Anglo-Saxon England." Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 273.1601 (2006): 2651-2657.

- ↑ Among other terms such as White Anglo-Saxon Protestant .

- ↑ Krüger: Vol. 2, pp. 449, 450 f.

- ^ Philippson: pp. 29, 30.

- ^ Philipsson: pp. 30, 31, 32, 34.

- ↑ Philipsson: pp. 35-37. Krüger: Vol. 2, p. 478.

- ↑ RGA: pp. 303-305.

- ↑ Eutrop , 9, 21: "Franks and Saxons who made the sea unsafe", around the year 285, 286.

- ^ Krüger: Vol. 2, p. 444.

- ^ Krüger: Vol. 2, pp. 476, 478. Archaeological excavation findings of the 1970s from Dorchester (Oxfordshire) and Croydon south of City of London, Mucking in Essex, Milton Right in Kent.

- ^ On the events of Henning Börm : Westrom. From Honorius to Justinian . Stuttgart 2013, p. 76 ff.

- ↑ Krüger: Vol. 2 p. 481; For the 5th and 6th centuries, Germanic settlement has only been proven for Dorchester and Canterbury.

- ^ Learning from the robbers ZEIT online, May 9, 2013.

- ↑ a b Beda, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum - The Church History of the English People 1.15.

- ↑ a b Krüger: Vol. 2 p. 477.

- ↑ Krüger: Vol. 2. P. 480, 481

- ↑ Among other places: Anderida ( Pevensey ), Calleva Atrebatum ( Silchester ), Deva ( Leicester ), Vriconium ( Wroxeter ), Durovernia ( Canterbury ).

- ↑ Krüger: Vol. 2 p. 481; Forms, locations and map index in Schleswig pp. 454, 455.

- ↑ Felix Liebermann: The laws of the Anglo-Saxons . ed. on behalf of the Savigny Foundation, Halle 1903. Reprint 2015.

- ^ John Blair: Building Anglo-Saxon England. Princeton University Press 2018.

- ↑ Clearly recognizable from the competitive situation of the later continental heathen mission between the Frankish and Anglo-Saxon missionaries of the 8th – 9th centuries. Century.

- ↑ Krüger: Vol. 2, p. 481

- ↑ Jan de Vries: The spiritual world of the Teutons . Darmstadt 1964, chap. 7th

- ^ Philipsson: p. 30.

- ↑ Arno Borst: Life forms in the Middle Ages . Ullstein, Berlin 1999. p. 386 ff.