Old English

| Old English Ænglisc | ||

|---|---|---|

| Period | approx. 450 to 1100 | |

|

Formerly spoken in |

Parts of what is now England and southern Scotland | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

nec |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

nec |

|

Old English , also Anglo-Saxon (own name: Ænglisc /'æŋ.glɪʃ/ , Englisc ), is the oldest written language level of the English language and was written and spoken until the middle of the 12th century. Old English originated when the Angles , Jutes , Frisians and Saxons settled in Britain from around 450 onwards . For speakers of New English, this language level can no longer be understood without specific learning. She is a closely related to the Old Frisian and Old Saxon related West Germanic language and belongs to the group of Germanic languages at, a main branch of the Indo-European family .

history

The Old English language split off from the continental West Germanic from the 5th century , when the Angles , Saxons , Frisians and Jutes , Germanic tribes from the north of today's Germany and Denmark, invaded Britain and settled there ( Battle of Mons Badonicus ). The language of the newcomers to Britain displaced the Celtic languages of the native population and is referred to as "Anglo-Saxon" (although the term "Old English" is used in today's literature). This language forms the basis for the English language. From the 8th century on, Old English was documented in writing and reached a certain degree of standardization around 1000 (the Old English dialect of late west Saxon of the "School of Winchester").

At the time of Old English, English formed a dialect continuum with the West Germanic languages on the mainland. The dialect speakers on the mainland and the island were able to communicate with each other, but since then the languages on both sides of the English Channel have developed so far apart that this former dialect continuum no longer exists.

From the Celtic languages previously spoken on the island, Old English adopted very few loan words. However, there is some opinion that the Celtic languages had some influence on the syntax of late Old English.

Another important event for the development of Old English is the Christianization of Britain from the 6th century. Through Christianization, many Latin loan words found their way into the Old English language, especially in the area of religious vocabulary.

In addition to Latin loanwords, there are also Scandinavian loanwords in English: This is related to the invasion of northwest England by Vikings from Norway. (Many invaders were referred to as "Danes", but they actually came from the Horthaland region in Norway.) Viking invasions began in the 8th century and continued through the 9th and 10th centuries. In 793 the northeast was raided on a large scale and the priory of Lindisfarne, an important center of learning in Old England, was devastated. In 866 East Anglia was sacked, and in 867 the city of York fell . The spread of the Vikings to the south and west was only stopped by King Alfred von Wessex after lengthy armed conflicts. In the Treaty of Wedmore 878 a border was drawn between the Kingdom of Wessex in the southwest and the domain of the Vikings (called " Danelag "). Due to the Danish and Norwegian immigration from the 8th century, Old English integrated numerous North Germanic elements in addition to Old Saxon , which, however, only appear in greater numbers in the Middle English texts.

The old English era ended with the conquest of England by the French Normans in 1066 . With the rule of the Normans over England, the influence of Norman French on the English language began and with it the period of the Middle English language .

Geographical distribution

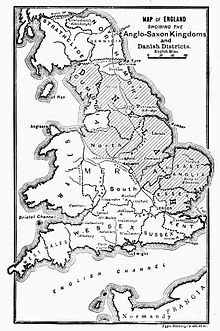

The four main dialects of the Old English language were North Humbrian , Merzisch (South Humbrian), Kentish and West Saxon , although there were a number of smaller dialects. Each of the main dialects can originally be assigned to an independent kingdom on the island. However, in the 9th century , Northumbria and most of Mercia were overrun by the Vikings, and the other parts of Mercia and all of Kent were incorporated into the Kingdom of Wessex .

After the unification of several Anglo-Saxon kingdoms by the West Saxon King Alfred the Great in 878, Alfred elevated the dialect of Wessex to the administrative language, so that the importance of West Saxon increased. For this reason, the written Old English texts are largely influenced by West Saxon, and the late West Saxon is regarded as a kind of standard that, due to its good tradition, is also used as a basis in many Old English textbooks.

Phonetics and Phonology

The following tables provide an overview of the vowels and consonants in Old English:

Vowels

| front | almost in front |

central | almost in the back |

back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ung. | ger. | ung. | ger. | ung. | ger. | ung. | ger. | ung. | ger. | |

| closed | i : | y : | u : | |||||||

| almost closed | ɪ | ʏ | ʊ | |||||||

| half closed | e : | ø : | o : | |||||||

| medium | ə | |||||||||

| half open | ɛ | œ | ɔ | |||||||

| almost open |

æ :

æ |

|||||||||

| open |

ɑ :

ɑ |

ɒ̃ | ||||||||

Each long vowel corresponded to a short vowel, e.g. B. / æ: / and / æ /. However, some short vowels were in a slightly lower or more central position than the corresponding long vowels, e.g. B. / u: / and / ʊ /.

The early West Saxon dialect of Old English has the following diphthongs:

| Diphthongs | Short | Long |

|---|---|---|

| First element is closed | ɪ ʏ | iy |

| Both elements are medium | ɛ ɔ | eo |

| Both elements are open | æ ɑ | æɑ |

Consonants

The consonants of Old English are:

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p b | t d | k g | |||||

| Affricates | tʃ (dʒ) | |||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | ||||

| Vibrants | r | |||||||

| Fricatives | f (v) | θ (ð) | s (z) | ʃ | (ç) | (x) (ɣ) | H | |

| Approximants | j | w | ||||||

| Lateral | l |

The sounds in brackets are allophones :

- [ dʒ ] is an allophone of / j / , which after / n / and Gemination occurs.

- [ ŋ ] is an allophone of / n / that before / k / and / g / occurs.

- [v, ð, z] are allophones of / f, θ, s / that appear betweenvowelsand / orvoiced consonants.

- [c, x] are allophones of/ h /occurring in Silbenauslaut,[ ç ]accordingfront voweland[ x ]toback vowel.

- [ ɣ ] is an allophone of / g / located between vowels and / or voiced consonant occurs.

The exact nature of Old English r is unknown. It could be a alveolar tap [ ɾ ] or alveolar Vibrant [ r ] have been.

grammar

Like other West Germanic languages of that time, Old English was an inflectional language with five cases ( nominative , genitive , dative , accusative and instrumental , which, however, mostly coincided with the dative), a dual still preserved in the personal pronouns of the 1st and 2nd person in addition to singular and plural . In addition, Old English, like German, had a grammatical gender for all nouns , e.g. B. sēo sunne (Eng. 'The sun') and se mōna (Eng. 'The moon').

vocabulary

The old English vocabulary consists mainly of words of Germanic origin. There are only a few loan words from other languages, according to estimates only about 3% of the Old English vocabulary. The loanwords come mainly from Latin, also from Old Norse and Celtic, which is due to the contact of the Anglo-Saxons with Romans and the Latin-speaking Christian Church, Scandinavians and Celts.

Despite the contact between the immigrant Anglo-Saxons and the Celtic indigenous people of Britain, Celtic loanwords are rare in Old English. Most of the loanwords that have come down to us are geographical names, especially river names, place names or parts of place names: The name of the Old English Kingdom of Kent goes back to the Celtic word Canti or Cantion , although its meaning is unknown. The names of the northern Humbrian kingdoms Deira and Bernicia go back to Celtic tribal names. Thames and Avon are Celtic river names. Celtic word components such as cumb (dt. 'Deep valley') can also be found as parts of place names such as Duncombe , Holcombe or Winchcombe . Apart from place names, there are only about a dozen examples of loanwords that can be traced back to a Celtic origin with some reliability: Probable candidates include binn (dt. 'Basket, crib'), bratt (dt. 'Coat'), brocc (dt. 'badger') and crag or luh (both dt. 'lake'). Other possible examples of Celtic loanwords such as carr (dt. 'Rock') or dunn (dt., Dark ') are controversial. The Celtic loanwords mostly come from Old British. There are also a few loan words from Old Irish, one of which is drȳ ( Eng . 'Magician').

Latin loanwords are far more common in Old English, and they mostly come from trade, military, and religion. The Anglo-Saxon tribes brought some Latin loanwords with them from the European continent before they immigrated to England, such as camp ( Eng . 'Field, fight', Latin. Campus ) or ċĕaster (Eng. 'Burg, Stadt', Latin. Castra ). A large proportion of Latin words came into the English language with the Christianization of England. Examples of Latin loanwords from the religious field that go back to the Old English period are abbot , hymn , organ , priest , psalm and temple . The Latin Church also exerted an influence on everyday life in the Old English period, so that loan words for household items such as cap , chest or map , and loan words for food such as caul (German for 'cabbage') or lent (German for 'lentils' ) were also used . ) finds. Words from the field of education and learning can also be found, e.g. B. school , master or verse . Through the Benedictine order in England, another set of Latin loanwords found their way into Old English, including Antichrist , apostle , demon and prophet . Overall, the number of Latin loanwords from the religious area is estimated at around 350–450 words.

In the middle to the end of the Old English Period, Scandinavian peoples invaded England; At times large parts of England were ruled by Scandinavian kings. Through the contact between Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavian invaders, Scandinavian loanwords also found their way into the English language. Examples are sky , skin , skill , reindeer or swain . Furthermore, many place names of Scandinavian origin have come down to us: In the east of England, where Danish invaders settled, you will find a large number of places that end in - by , the Danish word for place or yard : Grimsby , Whitby , Derby or Rugby are among them. In addition to nouns, verbs and adjectives, some pronouns have even been adopted from Scandinavian: The pronouns they / their / them replaced the original, old English forms hīe , hiera and him in the Middle English period at the latest .

Most of the Scandinavian loanwords, however, are not very well documented in Old English texts; the Scandinavian influence is only noticeable in the traditional texts from the Middle English period. Scandinavian loanwords, which are already used in old English texts, are e.g. B. cnīf (German 'knife', cf. Old Icelandic knífr ), hittan (German 'to meet', cf. Old Icelandic hitta ) and hūsbonda (German 'landlord', cf. Old Icelandic húsbóndi ).

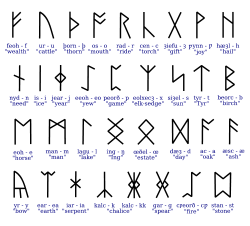

font

Old English was originally written with runes , but after conversion to Christianity it adopted the Latin alphabet , to which some characters were added. For example, the letter Yogh was taken from Irish , the letter ð ( eth ) was a modification of the Latin d , and the letters þ ( thorn ) and ƿ ( wynn ) come from Fuþorc (the Anglo-Frisian variant of the common Germanic rune series, the older Fuþark ).

The characters of the Old English alphabet correspond roughly to the following sounds:

Consonants

- b : / b /

- c (except in the digraphs sc and cg ): either / tʃ / or / k / . Pronunciation as / tʃ / is most often in today's text output by a diacritical mark indicated: mostly ċ, sometimes č or ç . Before a consonant, the letter is always considered / k / given; at the end of a word after i always considered / tʃ / . In other cases, one must know the etymological origins of a word in order to pronounce it correctly.

- cg : [ddʒ] ; occasionally also for / gg /

- d : / d /

- f : / f / and its allophone [ v ]

- g : / g / and its allophone [ ɣ ] ; / j / and its allophone [ dʒ ] (after n ). Pronunciation as / j / or [ dʒ ] is now often than ġ written. Before a consonant, it is always as [ g ] (letters) or [ ɣ ] pronounced (after a vowel). At the end of a word after i it is always / j / . In other cases, one must know the etymological origins of a word in order to pronounce it correctly.

- h : / h / and its allophones [ç, x] . In the combinations hl, hr, hn and hw , the second consonant was always voiceless.

- k : / k / (rarely used)

- l : / l / ; possibly velarized in the final syllable as in New English

- m : / m /

- n : / n / and its allophone [ ŋ ]

- p : / p /

- q : / k / - before the consonant / w / representing u used, but rarely. Old English preferred cƿ or, in modern notation, cw .

- r : / r / . The exact nature of Old English r is unknown. It could be a alveolar approximant [ ɹ ] have been, as in most modern English dialects, an alveolar tap [ ɾ ] or alveolar Vibrant [ r ] . In this article, we use the symbol / r / for this sound, without wishing to make a statement about its nature.

- s : / s / and its allophone [ for ]

- sc : / ʃ / or occasionally / sk /

- t : / t /

- ð / þ : / .theta / and its allophone [ ð ] . Both characters were more or less interchangeable (although there was a tendency not to use ð at the beginning of a word, which was not always the case). Many modern editions keep the characters as they were used in the old manuscripts, but some try to align it in some way according to certain rules, for example by using only þ .

- ƿ ( Wynn ): / w / , in modern notation by w replaced to confusion with p to avoid.

- x : / ks / (but according to some authors [xs ~ çs] )

- z : / ts / . Rarely used, ts were usually used instead , for example bezt vs betst “the best”, pronounced / betst / .

Double consonants are pronounced elongated ; the elongated fricatives ðð / þþ, ff and ss are always voiceless.

Vowels

- a : / ɑ / (spelling variations such as country / lond "land" suggest the presence of a rounded allophone [ ɒ ] before [ n ] in some cases close)

- ā : / ɑː /

- æ : / æ /

- ǣ : / æː /

- e : / e /

- ē : / eː /

- ea : / æɑ / ; after ċ and ġ sometimes / æ / or / ɑ /

- ēa : / æːɑ / ; after ċ and ġ sometimes / æː /

- eo : / eo / ; after ċ and ġ sometimes / o / or / u /

- ēo : / eːo /

- i : / i /

- ī : / iː /

- ie : / iy / ; after ċ and ġ sometimes / e /

- īe : / iːy / ; after ċ and ġ sometimes / eː /

- o : / o /

- ō : / oː /

- oe : / ø / (in some dialects)

- ōe : / øː / (only in some dialects)

- u : / u /

- ū : / uː /

- y : / y /

- ȳ : / yː /

Note: Modern editions of Old English texts use additional characters as reading aids to indicate long vowels and diphthongs. So z. B. short vowels like a , i or o are distinguished from long vowels like ā , ī or ō , ea , eo or ie are short diphthongs. The additional characters are not part of the original Old English script.

Text and audio samples

The Lord's Prayer in Old English (West Saxon):

|

Fæder ūre þū þe eart on heofonum |

Our father, you are in heaven, |

The following audio sample includes the Lord's Prayer in Old English:

Old English literature

The Beowulf - epic , written around 1000, but probably older, a Germanic heroic epic in rod rhyming long lines is one of the most famous pieces of Anglo-Saxon poetry. Furthermore, the Christian- religious poems of Cynewulf were written in the old English language.

The Caedmon manuscript with religious poems on Old Testament topics, the Exeter book ( see also: Exeter ) with poems on religious and secular topics, the Codex Vercellensis with sermons and smaller poems, as well as various legal texts in prose since the 7th century and Documents that have been written in Old English since the 8th century are further sources from which Anglo-Saxon is known as a literary language.

See also

literature

Introductions

- Albert C. Baugh, Thomas Cable: A History of the English Language . 6th edition. Routledge, London / New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-415-65596-5 .

- Richard Hogg, Rhona Alcorn: An Introduction to Old English . 2nd Edition. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2012, ISBN 978-0-7486-4238-0 .

- Keith Johnson: The History of Early English . Routledge, London / New York 2016, ISBN 978-1-138-79545-7 .

- Bruce Mitchell, Fred Robinson: A Guide to Old English. 7th edition. Blackwell, Oxford 2006, ISBN 1-4051-4690-7 .

- Wolfgang Obst, Florian Schleburg: Textbook of Old English. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-8253-1594-0 .

Grammars

- Karl Brunner: Old English grammar. Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1965.

- Alistair Campbell: Old English Grammar. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1959, ISBN 0-19-811943-7 .

Dictionaries

- Joseph Bosworth, Thomas Northcote Toller (Eds.): An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Based on the manuscript collections of the late Joseph Bosworth. Oxford University Press, 1954 (reprint). 2 volumes, of which the second is a supplement to the first.

- Clark JR Hall: A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. with supplement by Herbert D. Meritt. 4th edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1960.

Phonology

- Karl Brunner: Old English grammar (revised from the Anglo-Saxon grammar by Eduard Sievers). 3. Edition. Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1965.

- Alistair Campbell: Old English Grammar. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1959, ISBN 0-19-811943-7 .

- Fausto Cercignani : The Development of * / k / and * / sk / in Old English. In: Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 82/3 1983, pp. 313-323.

- Richard M. Hogg: A Grammar of Old English, I: Phonology . Basil Blackwell, Oxford 1992.

- Sherman M. Kuhn: On the consonantal phonemes of Old English. In: JL Rosier (Ed.): Philological Essays: studies in Old and Middle English language and literature in honor of Herbert Dean Merritt . Mouton, Den Haag 1970, pp. 16-49.

- Roger Lass, John M. Anderson: Old English Phonology . (= Cambridge studies in linguistics. No. 14). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1975.

- Karl Luick: Historical grammar of the English language . Bernhard Tauchnitz , Stuttgart 1914–1940.

- Eduard Sievers: Old Germanic metrics. Max Niemeyer, Halle 1893.

Old English literature

- Seamus Heaney (translator): Beowulf. Faber & Faber, London 1999. (Norten, New York 2002, ISBN 0-393-97580-0 )

- John RR Tolkien: Beowulf, the monsters and the critics. Sir Israel Gollancz memorial lecture 1936. Oxford University Press, London 1936. (Reprinted in Oxford 1971, Arden Library, Darby 1978)

Others

- Peter Bierbaumer: The botanical vocabulary of Old English. 3 volumes. Frankfurt am Main 1976.

Web links

- Michael DC Drout: Anglo Saxon Aloud - reading of old English texts

- Gerhard Köbler: Old English dictionary

- Gerhard Köbler: Online Dictionary Wikiling Old English (and other old languages)

Individual evidence

- ^ Theo Vennemann: English - German dialect? In: academia.edu . November 7, 2005, p. 16 ff. , Accessed on May 9, 2019 (English).

- ↑ Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, Heli Pitkänen (eds.): The Celtic Roots of English . University of Joensuu, Faculty of Humanities, Joensuu 2002 (English).

- ^ Keith Johnson: The History of Early English . Routledge, London / New York 2016, ISBN 978-1-138-79545-7 , pp. 27-32 (English).

- ^ Richard Hogg, Rhona Alcorn: An Introduction to Old English . 2nd Edition. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2012, ISBN 978-0-7486-4238-0 , pp. 125-128 (English).

- ↑ Wolfgang Obst, Florian Schleburg: Textbook of Old English . Winter, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-8253-1594-0 , p. 63 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Obst, Florian Schleburg: Textbook of Old English . Winter, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-8253-1594-0 , p. 65-66 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Obst, Florian Schleburg: Textbook of Old English . Winter, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-8253-1594-0 , p. 67 .

- ^ Richard Hogg, Rhona Alcorn: An Introduction to Old English . 2nd Edition. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2012, ISBN 978-0-7486-4238-0 , pp. 10 (English).

- ↑ Wolfgang Obst, Florian Schleburg: Textbook of Old English . Winter, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-8253-1594-0 , p. 107 .

- ^ Albert C. Baugh, Thomas Cable: A History of the English Language . 6th edition. Routledge, London / New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-415-65596-5 , pp. 71-72 (English).

- ^ Alistair Campbell: Old English Grammar . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1959, ISBN 0-19-811943-7 , pp. 219-220 (English).

- ↑ Wolfgang Obst, Florian Schleburg: Textbook of Old English . Winter, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-8253-1594-0 , p. 110-111 .

- ^ Albert C. Baugh, Thomas Cable: A History of the English Language . 6th edition. Routledge, London / New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-415-65596-5 , pp. 73-85 (English).

- ^ Albert C. Baugh, Thomas Cable: A History of the English Language . 6th edition. Routledge, London / New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-415-65596-5 , pp. 87-98 (English).

- ↑ Wolfgang Obst, Florian Schleburg: Textbook of Old English . Winter, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-8253-1594-0 , p. 113-114 .

- ^ Keith Johnson: The History of Early English . Routledge, London / New York 2016, ISBN 978-1-138-79545-7 , pp. 39-40 (English).

- ↑ Wolfgang Obst, Florian Schleburg: Textbook of Old English . Winter, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-8253-1594-0 , p. 69-71 .