North Sea Germanic languages

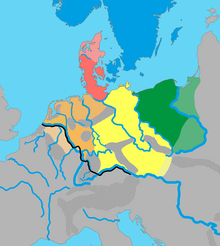

As North Sea Germanic languages (or Ingwaeonic languages ) different Germanic varieties are referred to in linguistics, which were widespread in the North Sea area around the middle of the first century and which had common characteristics. The descendants of these varieties are Frisian , Lower Saxony and Old English or English , which are accordingly often still classified as North Sea Germanic today. The Lower Franconian or Dutch is also sometimes included in this. Typical North Sea Germanic characteristics, so-called "Ingwaeonisms", can be found mainly in Frisian and English. Lower Saxon has lost many North Sea Germanic characteristics due to the early connection to Franconian or High German .

North Sea Germanic or Gingerian?

The adjectives North Sea Germanic and Gingwaean are now largely used synonymously. Further synonyms for this group of languages are Northwest Germanic , Coastal West German and Coastal German . The designation northwest Germanic is ambiguous, however, as it can also refer to the unity of North Germanic and West Germanic or to the unity of North Germanic and North Sea Germanic .

Ginger

This name can be found in the Roman writer Tacitus . In his work De origine et situ germanorum he reported on three Germanic cultures , of which the Ingaevones lived closest to the ocean. The Roman writer Pliny previously reported on the Inguaeones and Ingvaeones in his Naturalis historia .

The term is common in several spellings. In addition to the rare version ingaevonisch come ingävonisch , ingväonisch and the modern to the spelling adapted ingwäonisch and rarely ingäwonisch ago.

Based on the Ingaevones, who live on the North Sea according to this tribal classification, to which the Frisians , Saxons and Angles are counted among others , the term Ingwäonisch was chosen as a label for the linguistic features that the term Anglo-Frisian no longer did justice to . However, the term is often criticized because it can be understood as a direct reference to the unknown language of the Tacite Ingaevones.

North Sea Germanic

There is a tendency in linguistics to replace terms that refer to tribes with terms that do not. In the case of the term Ingwaeonian , the term North Sea Germanic is such a substitute. But this geographical name is also controversial, since North Sea Germanic features also occur deep in the Dutch and Low German inland areas. In addition, the term North Sea Germanic , unlike Gingwaean, is cumbersome and can only be used to a limited extent for other derived terms, e.g. B. "North Sea Germanisms".

North Sea Germanic languages

The discussion about North Sea Germanic / Ingwaeonic is still ongoing in science. The North Sea Germanic was and is judged differently.

The term Ingwaeon can still mean the same as the term Anglo-Frisian . In Ferdinand Wrede's ginger theory , the two terms have the same meaning.

However, in linguistics today, Ingwaeon is mostly equated with North Sea Germanic. The term North Sea Germanic comes from Friedrich Maurer's theory of the structure of the Germanic peoples and includes not only English and Frisian, but also Low German.

In addition to Old English and Old Frisian , Old Saxon is also one of the North Sea Germanic languages. However, Low German came under the influence of southern dialects: first Franconian after the subjugation of the Saxons by Charlemagne , then under High German influence. Low German has lost its North Sea Germanic character - apart from a few relics (Ingwaeonisms).

The Netherlands is assessed differently, it usually is not associated with the North Germanic, as it Frankish foot on dialects. However, Dutch has a North Sea Germanic substrate . These North Sea Germanic influences are sometimes viewed as a Frisian substrate, and sometimes not assigned to Frisian.

Viewpoints on the topic of "ginger"

The discussion about the North Sea Germanic languages is made more difficult by the fact that quite different theories are associated with the Ingwäons and their languages.

For example, the German linguist Ferdinand Wrede put forward a theory in 1924 according to which the Low German and Swabian-Alemannic regions formed a common Ingwaeon language area for a while, with common linguistic properties. According to Wrede's theory, “West Germanic” and “Anglo-Frisian” (Ingwäonisch) were originally the same. According to this theory, the Goths drove a wedge between the two areas on their migrations and separated them from one another. German is Gothicized "West Germanic" (Ingwäonisch). However, this theory has proven to be flawed.

Another exponent of radical ginger theories was the Dutch linguist Klaas Heeroma. Since 1935 he has repeatedly dealt with the Ingwaeon and often aroused contradictions with his theories.

The Dutch linguist Moritz Schönfeld, however, uses the term Ingväonisch very carefully. For him, this term is only a flexible dialectological term for mobile isogloss complexes, without reference to prehistoric tribes or unit languages. For him, the term is a label for linguistic phenomena on the coast, without any precise delimitation in space and time.

Features of the North Sea Germanic languages

Linguistic peculiarities of the North Sea Germanic languages are mostly called Ingwaeonisms . This term has become widely established, even if the term North Sea Germanic is often used. As is generally the case with North Sea Germanic, research opinions on Ingwaeonisms also differ. There is no agreement as to which characteristics belong to the gwaeonisms. Some examples are given below, without claiming to be complete or general:

- Nasal spiral law: failure of the nasal before fricative , with replacement stretching :

- Germanic * samftō, -ijaz 'gently' becomes westfries. sêft, engl. soft, lower German sacht, ndl. carefully

- germanic * goose 'goose' becomes westfries. goes, guos, engl. goose, Niederdt. Goos

- Omission of the t in the 3rd person singular of sein: Germanic * is (i) becomes oldgl. is, old Saxon is (next to is )

- Elimination of the r in the personal pronoun of the 1st person plural: Germanic * wīz 'we' becomes old Saxon. wī, wē, altndl. , old frieze. wī, oldgl. wē (opposite limb. veer, old north. vér, got. weis )

- Different stem of personal pronouns:

- German "he": Niederdt. he, ndl. hij, engl. hey, west frieze. hy, saterfrieze. hie, north frieze. Hi

- German "Ihr": Niederdt. ji, mndl. ghi, engl. you, westfries. jim, saterfrieze. jie, north frieze. jam

- 3- case system with no difference between dative and accusative

- Future tense formation with the auxiliary verb schallen (sallen), shall: fries. Ik schall (sall) - engl. I shall (German 'I will')

-

Assibilization of the plosive k in front of palatal vowels to a fricative :

- German "cheese": Engl. cheese, west frieze. tsiis, sater frieze . sies, north frieze . sees

- German "Church": Engl. church, west frieze. tsjerke, saterfrieze. seerke, north frieze . schörk, sark

- In Low German (especially Groningen - East Frisian ) almost disappeared except for relic words with Zetaism: Sever next to Kever 'Beetle'

- Palatalization of the Germanic a: Germanic * dagaz 'day' becomes old English. dæg, old frieze. dei; Latin (via) strata , street 'becomes old English. strǣt, old Frisian strēte

- Formation of the participle perfect without the prefix ge: Niederdt. daan, engl. done, west frieze. dien, saterfrieze. däin, north frieze . dänj (German 'done')

- r-metathesis : engl. burn, west frieze. baarne (next to brâne ), north frieze . baarn win 'burn' (next to braan 'burn') Niederdt. Barn steen 'amber' (next to burn 'burn')

- The verbal unit plural (Niederdt. Wi / ji / se maakt, Nordfries. We / jam / ja mååge - German “we do / you do / they do”) is often counted among the Ingwaeonisms.

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans Frede Nielsen: Frisian and the Grouping of the Older Germanic Languages. In: Horst Haider Munske (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Frisian. = Handbook of Frisian Studies. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2001, ISBN 3-484-73048-X , pp. 81-104.

- ^ Adolphe van Loey: Schönfeld's Historical Grammatica van het Nederlands. Kankleer, vormleer, woordvorming. 8. Pressure. Thieme, Zutphen, 1970, ISBN 90-03-21170-1 , chap. 4, p. XXV.

- ↑ Steffen Krogh: The position of Old Saxon in the context of the Germanic languages (= studies on Old High German. Vol. 29). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1996, ISBN 3-525-20344-6 , pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Celebrant carminibus antiquis, quod unum apud illos memoriae et annalium genus est, Tuistonem deum terra editum. Ei filium Mannum, originem gentis conditoremque, Manno tris filios adsignant, e quorum nominibus proximi Oceano Ingaevones, medii Herminones, ceteri Istaevones vocentur. - “With old chants they celebrate their common descent according to memory and tradition that the earth produced the god Tuisto . His son is Mannus , origin and founder of the family (the Teutons). They attribute three sons to Mannus, after whose names the Ingaevones closest to the ocean, the middle Hermions and the other Istaevones were named. "

- ↑ Pliny , Historia Naturalis , IV, 27, 28.

- ↑ a b Klaas Heeroma: On the problem of Ingwäonischen. In: Early Medieval Studies. Vol. 4, 1970, pp. 231-243, doi : 10.1515 / 9783110242041.231 (currently unavailable) .

- ^ Claus Jürgen Hutterer : The Germanic languages. Your story in outline. 2nd German edition. Drei-Lilien-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1987, ISBN 3-922383-52-1 , chap. IV.3.61, p. 243 and IV.4.52, p. 296.

- ↑ Coenraad B. van Haeringen: netherlandic Language Research. 2nd edition. Brill, Leiden 1960, p. 102.

- ^ Claus Jürgen Hutterer: The Germanic languages. Your story in outline. 2nd German edition. Drei-Lilien-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1987, ISBN 3-922383-52-1 , chap. IV.3.3; Adolf Bach : History of the German language. 9th, revised edition. Quelle & Meyer, Heidelberg 1970, p. 88, § 50.

- ↑ Coenraad B. van Haeringen: netherlandic Language Research. 2nd edition. Brill, Leiden, 1960, pp. 102-104.

- ^ Adolphe van Loey: Schönfeld's Historical Grammatica van het Nederlands. Kankleer, vormleer, woordvorming. 8. Pressure. Thieme, Zutphen, 1970, ISBN 90-03-21170-1 , chap. IX, p. XXXIII.

- ^ Adolphe van Loey: Schönfeld's Historical Grammatica van het Nederlands. Kankleer, vormleer, woordvorming. 8. Pressure. Thieme, Zutphen, 1970, ISBN 90-03-21170-1 , chap. 9, p. XXXIII.