Æthelberht (Kent)

Æthelberht I. (also Æþelbryht, Æþelbyrht, Aedilberct, Eðilberht, Eþelbriht or Ethelbert ) (* around 552/560; † February 24, 616/618) was the first Christian king of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom at the turn of the 6th to the 7th century Kent from the Oiscingas dynasty . He is venerated as a saint .

Life

The dates of the sources of Æthelberht are contradicting themselves and among themselves and are the subject of controversial discussion.

family

Æthelberht was a son of King Eormenric of Kent . His mother is unknown. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , he was born in the year 552. According to modern historians, however, the birth is more likely to be around 560. Through his sister Ricola , who was married to Sledda , he was associated with the Essex royal family.

Around 580 the pagan Æthelberht married Bertha , the Christian daughter of the Merovingian king Charibert I and Ingoberga . Gregory of Tours called Æthelberht in this context filius regis ("son of the king"), from which historians conclude that his father Eormenric was still alive at that time. While some assume an early date of 560 for Eormenric's death, others believe it to be around 585/590. It is therefore unclear whether the heathen Eormenric had the opportunity to influence his son's choice of bride. Æthelberht initially remained a heathen, but was religiously tolerant and did not prevent Bertha from practicing her faith. From this marriage Æthelberht's son Eadbald and probably his daughter Æthelburg emerged. According to Christian legend, Eadburh, Abbess of Liming, was also his daughter. After Bertha died around 610 Æthelberht married again. The name of this queen has not been passed down. After Æthelberht's death in 616/618, Eadbald married his stepmother.

Domination

Æthelberht ascended the throne between 580 and 593. Around 590 he tried unsuccessfully to wrest control of southern England from Ceawlin of Wessex . He marched into the region between Andredsweald and Thames (south of London), but was beaten by Ceawlin and his brother Cutha at Wibbandune ( Wimbledon ?) And pursued as far as Kent.

Augustine landed on the Isle of Thanet in 597 . The influence of Bertha, who brought her chaplain Liudhard (or Letard) with her to Kent, may have prompted Æthelberht to welcome the missionaries that Pope Gregory I sent from Rome . Æthelberht met him for the first time in the open air, in the belief that he could use it to drive away Christian magic. He soon allowed Augustine and the missionaries to settle in Canterbury and preach and missionize there. Legend has it that Augustine baptized him at Pentecost in 597 . 10,000 Anglo-Saxons are said to have followed his example within a few months. A letter from Gregory to Bertha, in which he reprimanded her for neglecting her husband's conversion, suggests that this could not have happened before 601. In another letter, however, Gregor emphasized Æthelberht's contribution to the spread of Christianity. Æthelberht and Augustinus had an old church in Canterbury rebuilt as a cathedral and founded a monastery, today's Abbey of St. Augustine . In Rochester , the Æthelberht founded St Andrew's Church and established a second bishopric , which he furnished with lands.

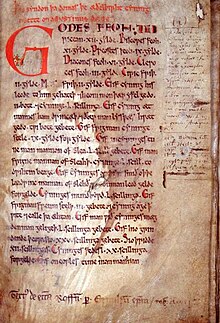

After Ceawlin's death around 593, Wessex's supremacy waned. Æthelberht, who had entered into an alliance with Europe's most powerful state at the time, gained influence and was recognized as the third Bretwalda around 600 south of the Humber . The associated abundance of power and the actual sphere of influence are unknown, but at least in Essex and East Anglia he was able to exert influence. Æthelberhts influence was strong enough around 602/603 that he could take over the patronage of a bishops' conference in the border area between Wessex and Hwicce , far outside the Kentish heartland. Also around 602/603, Æthelberht had a code of law written down in the vernacular, presumably with Augustine's assistance. The newly established church was also integrated into the Anglo-Saxon legal system. It was one of the earliest documents written in Old English . Detailed staggered fines were imposed for crimes. Beda Venerabilis reported that the laws were still in force around the year 730.

Æthelberht I. converted his nephew Sæberht to Christianity before 604 and was his godfather. Æthelberht installed him as King of Essex and had a bishopric for Essex set up in London , which was occupied by Bishop Mellitus . Also Rædwald , the king of East Anglia, was able to “persuade” Æthelbert to accept the Christian faith around 604.

Æthelberht died on February 24, 616 and was buried next to his wife Bertha in the Martinskapelle, the mausoleum of the abbey church "Peter and Paul" in Canterbury. Some historians also consider 618 as the likely year of death. His son Eadbald succeeded him as King of Kent while Rædwald was recognized as Bretwalda from that time.

Adoration

Æthelberht, also popularly called "Saint Albert", was probably venerated as a saint soon after his death because of his services to the spread of Christianity. The cult has been documented since the 13th century. His relics were reburied under the high altar of the original burial church. His feast day was originally February 24th, but today it is celebrated on February 25th so that it does not overlap with the feast day of the apostle Matthias . In iconography , he is represented in a vision of how he sees the man of pain or his instruments of suffering.

swell

- The Laws of Æthelberht in the Medieval Sourcebook (English)

- Beda Venerabilis : Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum , Online in the Medieval Sourcebook (English)

- anonymous: Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , online in Project Gutenberg (English)

- Nennius : Historia Brittonum , Online in the Medieval Sourcebook (English)

literature

- Michael Lapidge, John Blair, Simon Keynes, Donald Scragg (Eds.): The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford et al. a. 2001, ISBN 978-0-6312-2492-1 .

- Nicholas Brooks : Anglo-Saxon Myths: State and Church, 400-1066 , Hambledon & London, 1998, ISBN 978-1852851545 ; especially Æthelberht , pp. 47–51.

- Barbara Yorke : Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England . Routledge, London-New York 2002, ISBN 978-0-415-16639-3 . PDF (6.2 MB)

- Nicholas J. Higham: The convert kings: power and religious affiliation in early Anglo-Saxon England , Manchester University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0719048289 , esp. King Æthelberht: conversion in context , p. 53 ff.

- DP Kirby: The Earliest English Kings , Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0415242110 , esp. The Reign of Æthelberht , p. 24 ff.

- William Hunt : Ethelbert (552? -616) . In: Leslie Stephen (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 18: Esdaile - Finan. MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London, 1889, pp 16 - 17 (English).

- Ekkart Sauser : Ethelbert. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 18, Bautz, Herzberg 2001, ISBN 3-88309-086-7 , Sp. 391-392.

- Brooks NP: Æthelberth . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 1, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7608-8901-8 , Sp. 187.

Web links

- Æthelberht I in Foundation for Medieval Genealogy

- Saint Ethelbert of Kent at Saints.SQPN.com

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Nicholas Brooks: Anglo-Saxon Myths: State and Church, 400-1066 , Hambledon & London, 1998, ISBN 978-1852851545 , pp. 47-51.

- ↑ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 552

- ↑ a b c Simon Keynes: Kings of Kent . In: Lapidge et al. (Ed.): The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford et al. a. 2001, ISBN 978-0-6312-2492-1 , pp. 501-502.

- ↑ Nicholas J. Higham: The convert kings: power and religious affiliation in early Anglo-Saxon England , Manchester University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0719048289 , pp. 85-86.

- ^ Gregory of Tours : Historia Francorum ( History of the Franks ) 9.26

- ↑ a b c d e S. E. Kelly: Æthelberht ; In: Michael Lapidge et al. (Ed.): The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford et al. a. 2001, ISBN 978-0-6312-2492-1 , p. 13

- ↑ DP Kirby: The Earliest English Kings , Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0415242110 , pp. 25-26.

- ^ A b c d William Hunt : Ethelbert (552? –616) . In: Leslie Stephen (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 18: Esdaile - Finan. MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London, 1889, pp 16 - 17 (English).

- ↑ between 601 and 616: Berta in Foundation for Medieval Genealogy

- ^ DP Kirby: The Earliest English Kings , Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0415242110 , p. 46.

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 568

- ↑ Beda: HE 1.25

- ↑ a b Ekkart Sauser : Ethelbert. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 18, Bautz, Herzberg 2001, ISBN 3-88309-086-7 , Sp. 391-392.

- ↑ S1

- ↑ DP Kirby: The Earliest English Kings , Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0415242110 , pp. 29-30.

- ↑ DP Kirby: The Earliest English Kings , Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0415242110 , p. 30.

- ↑ The Laws of Æthelberht in the Medieval Sourcebook (English)

- ↑ Beda: HE 2.5

- ↑ Beda: HE 2,3

- ^ Ian Hodder: Interpreting Archeology: Finding Meaning in the Past , Routledge, 1997, ISBN 978-0-415-15744-5 (Paperback), p. 207.

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 604

- ↑ Beda: HE 5.24

- ^ A b Nicholas J. Higham, Rædwald , in: Lapidge et al. (Ed.): The Blackwell Enzyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England , p. 385.

- ↑ Ethelbert of Kent in saintpatrickdc.org

- ^ Saint Ethelbert of Kent at Saints.SQPN.com

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Eormenric |

King of Kent 560? / Around 585–616 / 618 |

Eadbald |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Æthelberht |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ethelbert; Æþelbryht; Æþelbyrht; Aedilberct; Eðilberht; Eþelbriht |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Kent |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 6th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 7th century |