Bretwalda

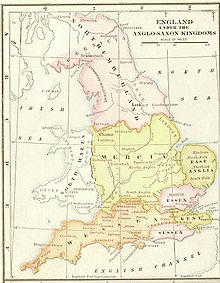

Bretwalda ("widely ruler") is a term from Anglo-Saxon England that was used in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle . The compilation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle began in the late 9th century , using annals and lists of kings from earlier times. In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, several rulers of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms from the 5th to the early 9th centuries are referred to with the term Bretwalda .

term

In Manuscript A of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the so-called Parker Chronicle , the word Bretwalda is used only once, namely in an entry that refers to the conquest of Mercia by the West Saxon King Egbert :

... he wæs se eahteþa cyning se þe bretwalda wæs.

In this context, Bretwalda is understood as the ruler of Britain, and it is implicitly assumed that Egbert had a special status as overlord.

In the same entry, the names of the seven other kings are given in chronological order:

- All of Sussex (circa 477-circa 514)

- Ceawlin of Wessex (560? -Circa 591)

- Æthelberht of Kent (591–616)

- Rædwald of East Anglia (616–627)

- Edwin of Northumbria (627-632)

- Oswald of Northumbria (633–641)

- Oswiu of Northumbria (641–670)

So there are more than 150 years between the death of Oswius and the mention of Egbert as Bretwalda in the chronicle.

In the other manuscripts of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, however, the same entry is reproduced with a different Old English word, namely a compound whose first element is based on a different root: the Abingdon Chronicle I (MS B) uses the word brytenwalda , the Abingdon Chronicle II (MS C) bretenwealda , the Worcester Chronicle (MS D) and the Peterborough Chronicle (MS E) brytenwealda , and the manuscript F brytenweald . This Old English compound denotes a powerful ruler or a ruler over a wide area. No reference is made to Britain, whereby the meaning of the first element is derived from the Old English verb breotan, which means “distribute”, “spread”, “spend” and is therefore interpreted as “prevailing”.

In the form of brytænwalda , the term appears later in an Old English interpolation in a spurious charter of King Æthelstan of England. However, he ruled from 925 to 939, and at that time the original meaning of the term may have been forgotten and, in the course of his claim to all areas of Britain, including Wales and Scotland, may have been interpreted and used as the “ruler of Britain”.

The author of the entry for the year 829 in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle took the term and enumeration of the church history of the English people from the Northumbrian monk Bede . However, in the Latin original Bede did not report about kings who were rulers of Britain, but used the noun imperium or the verb imperare to express the extent of the power that these rulers had. Empire could denote different forms of authority and government power. Bede also used imperium and imperare for stylistic reasons. On the one hand, he used it as a variant of regnum in order to avoid its repetition; on the other hand, Bede preferred the word imperium to denote worldly realms, while he rather referred to the heavenly kingdom as regnum . If the concept of a sovereign with quasi-imperial characteristics had existed in Anglo-Saxon England in Beda's time, he would have used the existing word imperator for it. However, there are only isolated cases in which parallels with the elevation to emperor on the battlefield based on the Roman model have been suggested. One such example is the endowment of the mercian king Cenwulf with imperial titles after the conquest of the kingdom of Kent , although this only seems to have been done to emphasize his abundance of power.

Bede tried to create the image of England made up of a closed entity. However, the Mercian kings were not represented in his list of rulers who had the empire , even though, for example, King Penda had destroyed an army of Northumbria with Welsh allies in 633 and was able to exercise supremacy over the previously dominant Northumbria. The fact that Penda had allied himself with the Welsh and was a pagan should not have affected the importance of Penda to Bede, since other pagan kings, Æll and Cealwin, are very well represented on his list. However, Ælle and Cealwin were named to reflect a certain geographical and temporal equilibrium within Anglo-Saxon England. Bede also mentions in his church history that in the year 731 all southern provinces, i.e. all areas south of the river Humber , were subject to the Mercian king Aethelbald , whereby he ascribed to him the same power as the other kings he had endowed with the empire . The fact that none of the Mercian kings as the imperium held wealthy or later than Bretwalda was referred to is, due to the fact that Bede wrote from Northumbrian view and that the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle at a time in Wessex edited was where Mercia, especially in the West Saxon Kingdom was incorporated, a development that began with Mercia's defeat by King Egbert in 829.

The term Bretwalda is thus a subjectively used term that was used towards the end of the 9th century to illustrate the power and claim to power of the dominant kingdom of Wessex. At no time was Bretwalda an institution or even a title in Anglo-Saxon England that would have been officially awarded to a ruler and which would have given him certain rights and sovereignty over other rulers.

reception

The use of the word Bretwalda in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to describe the status of King Egbert, as well as previous kings, whose names were taken from Beda's Church history of the English people , gave historians reason to believe that there would have been a title used by overlords in Anglo-Saxon Britain was carried. This concept was particularly tempting as it would have laid the foundation for the establishment of an "English" monarchy. Frank M. Stenton postulated in 1943 that the inaccuracy of the writer of the corresponding passage in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle would be more than made up for by the preservation of the English title, which was transferred to these outstanding rulers. The term Bretwalda fits in with other evidence that points to a Germanic origin of the earliest English institutions. However, this view has been increasingly called into question since the second half of the 20th century. It is therefore unlikely that the term was ever used as a title or was in common parlance in Anglo-Saxon England. The fact that Bede did not mention a specific title for the kings on his list suggests that there was no such title in his day. Both Beda's concept of an overlord south of the Humber and that of a Bretwaldas , which the writer of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle seeks to convey, are artificial concepts that have no justification outside the literary context in which they appear. According to these thoughts, one can say goodbye to assumptions and theories relating to political developments based on and connected with these concepts. It is more than questionable whether the kings of the 8th and 9th centuries were fixated on the establishment of an all-South Humbrian empire.

In more recent interpretations, the term Bretwalda is therefore seen as a complex concept. It is currently recognized as providing an important clue as to how a 9th-century chronicler interpreted history and tried to fit the West Saxon kings, who were rapidly expanding their power at the time, into that history.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ ASC MS A , s. a. 829

- ↑ Barbara Yorke, 'The Vocabulary of Anglo-Saxon Overlordship,' p. 171

- ↑ JM Kemble, The Saxons in England , II, p. 52

- ^ PH Sawyer, Anglo-Saxon Charters , no. 427

- ↑ Beda, HE , II, 5

- ^ W. Levison, England and the Continent in the Eight Century, p. 122

- ↑ Barbara Yorke, 'The Vocabulary of Anglo-Saxon Overlordship,' p. 176ff

- ↑ Beda, HE , V, 24

- ^ FM Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England , p. 34f.

- ^ S. Fanning, 'Bede, Imperium, and the Bretwalda,' p. 24

- ^ S. Fanning, 'Bede, Imperium, and the Bretwalda,' p. 23

- ^ S. Keynes, 'England, 700-900,' p. 39

literature

swell

- Anglo-Saxon Charters: An Annotated List and Bibliography, Peter Hayes Sawyer (Ed.), Royal Historical Society, London 1968, ISBN 0-9010-5018-0 .

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: MS A v. 3 , Janet Bately (Ed.), Brewer, Rochester (NY) 1986, ISBN 0-85991-103-9 .

- Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People , B. Colgrave & RAB Mynors (Eds.), Clarendon, Oxford 1969, ISBN 0-19-822202-5 .

Secondary literature

- Steven Basset (Ed.): The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Leicester University Press, Leicester 1989, ISBN 0-7185-1317-7 .

- James Campbell (Ed.): The Anglo-Saxons . Phaidon, London 1982, ISBN 0-7148-2149-7 .

- Steve Fanning: Bede, Imperium, and the Bretwaldas , in: Speculum 66.1 (1991) 1-26.

- Peter Hunter Blair: Roman Britain and Early England. 55 BC - AD 871. 2nd edition. Cardinal, London 1975, ISBN 0-351-15318-7 .

- John Mitchell Kemble : The Saxons in England. A History of the English Commonwealth till the Period of the Norman Conquest . B. Quartich, London 1876.

- Simon Keynes: England, 700-900. In: Rosamond McKitterick (Ed.): The New Cambridge Medieval History . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995, ISBN 0-521-36292-X .

- DP Kirby: The Earliest English Kings . Unwin Hyman, London et al. 1991, ISBN 0-04-445691-3 .

- Wilhelm Levison : England and the Continent in the Eight Century . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1946.

- Frank M. Stenton: Anglo-Saxon England . 3. Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1971, ISBN 0-19-280139-2 .

- Patrick Wormald: Bede, the Bretwaldas and the Origins of the Gens Anglorum. In: Patrick Wormald et al. (Ed.), Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society . Studies Presented to JM Wallace-Hadrill. Blackwell, Oxford 1983, ISBN 0-631-12661-9 , pp. 99-129.

- Barbara Yorke: The Vocabulary of Anglo-Saxon Overlordship . In: David Brown, James Campbell, Sonia Chadwick Hawkes: Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archeology and History . Volume 2. BAR, Oxford 1981, ISBN 0-86054-138-X , pp. 171-200 ( BAR British Series 92).

- Barbara Yorke : Kings and Kingdoms of early Anglo-Saxon England . Routledge, London-New York 2002, ISBN 978-0-415-16639-3 . PDF (6.2 MB)