Scots

| Scots (Scots, Lallans) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

|

|

| speaker | 1.5 million | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

sco |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

sco |

|

As (Lowland) Scots , also Lallans , a West Germanic language or number of English dialects referred to in Scotland in the central lowlands - but not in the (former) Scottish-Gaelic -speaking area of the Highlands and Hebrides - are spoken and in the mountainous southern Scotland , in Greater Glasgow-Edinburgh and in a strip of land along the east coast to Aberdeen . An investigation by the General Register Office in 1996 found a number of speakers of around 1.5 million people, or around 30% of the population of Scotland. Scots is also spoken in the parts of Northern Ireland and Donegal that were colonized by Scots in the 17th century; here it is spoken by both Protestants and Catholics , but promoted as a language of the Protestant population for ethnopolitical reasons.

Lowland Scots can be clearly distinguished from Scottish English - today's official and educational language of Scotland. Some now consider Scots to be a single language .

Dialects

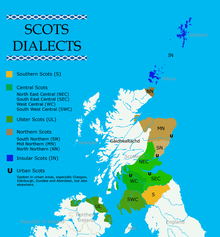

Scots is divided into at least five dialect groups:

- Island Scottish : the dialects of the Orkneys and Shetlands

- Northeast Scottish , also Northern Scots or Doric : the dialects of Northeast Scotland, essentially the Grampian region

- Central Scottish or Middle Scottish : the dialects of central and southwestern Scotland

- South Scottish : the dialects in the border area, ie the Borders

- Ulster Scots : dialects (Ullans) spoken in Northern Ireland and Donegal which, from a linguistic perspective, are considered to be a sub-dialect of Middle Scottish

The traditional dialects, i.e. a coherent, autonomous system of sounds and forms and an autonomous vocabulary showing dialects in the north-east and on the islands, have been preserved best, whereas the dialects of central and southern Scotland are heavily anglicized, albeit to different degrees. The city dialects of Aberdeen, Dundee , Edinburgh and Glasgow are indeed Scots-based, but strongly permeated by Scottish English and generally British city dialect characteristics. The traditional Scottish is often referred to as Braid / Broad Scots, the more anglicized as Urban Scots .

There has never been a standardized, over-dialectal form since the fall of the Scottish written language in the Middle Ages. There are some conventions for the spelling of the dialects, but they are adhered to in different ways; otherwise it can be largely phonetically depending on the writer. In other words: whoever writes Scots, writes according to their own language habits.

history

Scots goes back to the northern variant of the Anglo-Saxon language of the Kingdom of Northumbria ( North Humbrian ), to this day there are similarities to Northeast English dialects such as Geordie . After the destruction of this kingdom in the Viking Age in the 8th – 10th centuries. In the 19th century, when the Scandinavian settlers of the Danelag did not succeed in bringing northern Northumbria under their control, the Scottish King Constantine II was able to finally incorporate the region into Scotland with the battles of Corbridge in 912 and 918. As a result of these developments and settlements, the Scots, as well as the North English dialects, have a greater influence on the Old Norse language than in the South English dialects.

This Anglo-Saxon language of southern Scotland, which came under the influence of Middle English since the 12th century, was called Inglis by its speakers . In the southeast of the Lowlands , this language gradually supplanted Scottish Gaelic and the British language of the former Kingdom of Strathclyde , which was also conquered by Scotland in the 10th century , and Kumbrian , which became extinct in the 11th century.

The language border to Scottish Gaelic ran along the Firth of Forth until the 13th century . From the end of the 13th century, it spread further into the interior of Scotland, mainly through the burghs , proto-urban institutions that were first established under King David I (1124–1153). The majority of its inhabitants were English immigrants (especially from Northumbria and Huntingdonshire ), Flemings and French . While the country's military aristocracy spoke Gaelic and Norman French , by the end of the 13th century these small urban communities appear to have used Inglis as their lingua franca .

However, as a result of the Scottish Wars of Independence under William Wallace and Robert the Bruce , the Inglis- speaking population of Lothian had to accept Scottish rule and identity. At the same time, the English language gained in prestige in the 14th century compared to French, which also disappeared more and more at the Scottish royal court, and became the predominant language in most of southern and eastern Scotland and in the area around Aberdeen .

In addition to Old and Middle English, Old Norse and Gaelic, Dutch and Middle Low German also influenced the Scots through trade and immigration from these areas . Romance influence also came through Church Latin and Jurisprudence, Norman and Parisian French as a result of the Auld Alliance with the Kingdom of France . Overall, the Norman-French influence in the Scots, who came to the islands with the Norman conquest in the 11th century and only briefly reached the south of Scotland with the Norman-English suzerainty in the lowlands at the end of the 11th and beginning of the 12th century , is clear less than in the English language.

The Scottish royal court and the nobility were initially bilingual Gaelic and Inglis and then completely switched to the latter. By the end of the Middle Ages , Gaelic had been pushed almost entirely back into the Highlands and Islands, although some places in Galloway and Carrick were Gaelic until the 17th or 18th centuries. In the late 14th century, Inglis also replaced Latin as the language of administration and literature. It was not until the beginning of the 16th century that the language was referred to as Scots , while Gaelic, which had previously been named, was now increasingly referred to as Erse ("Irish"). In the Scottish Reformation , the use of Scots as the written and liturgical language of the Church of Scotland played an important role.

The process of spreading Scots continued after the union with England in 1603 into Northern Ireland's Ulster and the east of Scotland, with not only Gaelic being pushed back further into the Highlands, but also the former Nordic language of the Orkneys and Shetland Norn in the 18th century disappeared.

With the expansion of book printing from England in the 16th century, but especially with the personal union of Scotland and England in 1603, Scottish English , which was more oriented towards the written language of England but was interspersed with the influences of Scots, spread as a standard and written language .

In the course of the increased sovereignty of England since the Realunion for the formation of Great Britain in 1707 and with the urbanization in the course of industrialization since the end of the 18th century, a stronger linguistic Anglicisation set in in Scotland , especially in the southern industrial centers. Some poets continued to use and cultivate Scots and strove for a renaissance of the language around the 19th century. While practically the entire population of Scotland now speaks (Scottish) English at a native level, around 30% state that they can also speak Scots, and the proportion of Gaelic speakers is even lower. Today the same speakers often use the high-level Scottish English and the “popular” Scots side by side, depending on the social situation.

Text sample

The Christmas story ( Mt 1,18ff EU ) from the Lorimer Bible (20th century, East Central Scottish ):

- This is the storie o the birth o Jesus Christ. His mither Mary wis trystit til Joseph, but afore they war mairriet she wis fund tae be wi bairn bi the Halie Spírit. Her husband Joseph, honest man, hed nae mind tae affront her afore the warld an wis for brakkin aff their tryst hidlinweys; an sae he wis een ettlin tae dae, whan an angel o the Lord kythed til him in a draim an said til him, “Joseph, son o Dauvit, be nane feared tae tak Mary your trystit wife intil your hame; the bairn she is cairrein is o the Halie Spírit. She will beir a son, an the name ye ar tae gíe him is Jesus, for he will sauf his fowk frae their sins. ”

- Aa this happent at the wurd spokken bi the Lord throu the Prophet micht be fulfilled: Behaud, the virgin wil bouk an beir a son, an they will caa his name Immanuel - that is, “God wi us” .

- Whan he hed waukit frae his sleep, Joseph did as the angel hed bidden him, an tuik his trystit wife hame wi him. But he bedditna wi her or she buir a son; an he caa'd the bairn Jesus.

There is no lexeme in this excerpt that is completely foreign to the English language, but several forms correspond to outdated or rare English vocabulary or are used slightly differently than in the written language: tryst (agreement), ettle (try, intend), kithe (point ), bouk (belly), bairn (child). Hidlinweys is a formation that occurs only in dialect from English hidden and way (for example: hidden), with the meaning "secretly". O and wi are derived from of and with , and een from even , but frae is only indirectly related to the obvious from and corresponds more to English fro . The negation bedditna (English: bedded not ) looks ancient. Otherwise, one observes in this text the effects of the Tudor Vowel Shift , a vowel shift of the early modern period, which took place differently in Scotland and northern England than in the south. Where English has a mute <gh>, <ch> is written in Scots and spoken like in German: micht (English might , German would like ); where this does not occur, this dialect writer omits the consonants entirely: throu (spoken exactly like standard English through ).

Further examples

Jokingly, the Scots let English visitors try the following sentence, in which the for that difficult / ch / sound occurs several times: It's a braw, muin-licht does not break the (“Tonight the moonlight is beautifully bright!”, Literally: “ It is a beautiful bright moonlit night this night. ”). Another typically Scottish, “ui” written sound is / ø / (originated from old English long / oː /), which today only exists in island Scottish and is otherwise mostly rounded to / ɪ / and / e /; an example is the muin (moon) mentioned in the above quote, spoken / møn / or rounded central Scottish / men /, northeast Scottish / mɪn /, depending on the dialect.

The North Humbrian dialect of Old English, from which today's Scottish and North English dialects come, had an increased number of Danish loanwords due to cultural contacts . Therefore Scots example, has the original Nordic form kirk for "church" (English church ). Scots also has a few loanwords from Gaelic ; an example is braw (beautiful).

Other popular dialect words are wee (small), which is interestingly doubled as a trivializing toilet lexem in Scottish children's language : wee-wee (urine stream); bonnie (pretty), a loan word from French ( bonne ), which perhaps comes from the time of the " Auld Alliance " between Scotland and France against England; and the Gaelic loan word loch (lake), mostly a freshwater lake, but also in connection with sealoch as a name for the West Scottish " fjords ". French loanwords are less common than in English (see examples on the right).

The terms loon (boy) and quine (girl ) are typically Northeast Scottish ( Aberdeen and the surrounding area), the latter related to Old Norse kvinna (woman) and English queen (queen), but already a separate lexeme in Old English. The change from the breathy / wh / to a / f / is also north-east Scottish: fit = Centralbelt whit (English what ) (greeting in Aberdeen: fit like? About “how are you?”).

However, some examples are mostly bias preferences. One likes to draw the equation: English know = Scots ken . This is true, but hides the fact that ken also exists in standard English with a different meaning ( ken with the meaning "know" is found in the English dictionary with the name "Scottish"), while knaw is also in the Concise Scots Dictionary , of course in Scottish is just archaic. What is true is that the Scots use k often, the English less often. In northeast Scotland, the phrase Ken this? often used as a sentence introduction, such as English Know what? Other words that are commonly regarded as Scots, but also belong to the poetic language of Standard English, are aye (ja), lad (die) (boy), lass (ie) (girl).

literature

Scotland has made a relatively large contribution to English literature , but mainly in the standard English language. Scots is used comparatively rarely in the literature. In the Middle Ages , each region had only written its own language form, so the Renaissance poets Robert Henryson and William Dunbar wrote an early form of Scots (which they called inglis ). The period between the 15th and 17th centuries can be regarded as the marriage of the Scots, when a relatively standardized version was the language of prestige of the nobility and bourgeoisie and the language of the official administration of the kingdom. Since the introduction of the printing press , however, the transition to standard English forms began and Scots was only written when one wanted to conjure up a rural idyll for romantic reasons, or wanted to express nostalgia or a sense of home. Consequently, Scots is primarily a language for poetry, such as in the Jacobite mocking song Cam Ye O'er Frae France from the early 18th century; Dialect poetry first gained wider popularity when Robert Burns published folk songs in the peasant vernacular in the late 18th century and mimicked them in his own poems. Burns is considered to be the greatest dialect writer in Scotland. In other forms, Scots is very rarely used. In Scottish novels, Scots are typically found in the dialogue but not in the narrative - the classic example here is Sir Walter Scott . When Lorimer's translation of the Bible (see above) was published in 1983, it was very well received, but was mostly read in nostalgic, popular gatherings, rarely in churches.

In the early 20th century, the Lallans Society tried to bring together elements of the various dialects in order to produce a language that could also be used for formal purposes. A conscious attempt was made to bring outdated vocabulary back to life in order to make the differences between Scots and English more striking. Hugh MacDiarmid is the best-known example of a scribe who not only draws his Scots from his own environment, but also adorns it from dictionaries. However, it is significant that MacDiarmid is famous only for his poetry. Overall, the Lallans Society was not well received, as the majority of speakers rejected the language form as written language.

Since the Scottish Parliament was opened in 1999, there seem to have been renewed attempts to use Scots for formal purposes. For example, Parliament’s website is tentatively posting translations of some legal texts into Scots. It remains to be seen how these texts will be received by the population. By and large, they are ridiculed by the press.

Scots as a separate language

Scots is classified as a dialect (group) of English on the one hand or as a separate language on the other. Scots was used as the official language until the union with England in 1707.

The UK has recognized Scots as a regional language under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages .

In Northern Ireland, Ulster Scots has been gaining new status as part of the peace process since the 1990s. Since the Catholic-Republican population was granted an extended recognition of Irish, the Protestant-Unionist side insisted on equality of their special language, which suddenly assumed an explosive political status.

literature

Brief but well-founded overview:

- David Murison: The Guid Scots Tongue. 2nd Edition. William Blackwood, Edinburgh 1977, 1978 (reprinted).

Language history:

- Billy Kay: Scots, The Mither Tongue. London 1986 (reissued since).

Dictionaries:

- The Scottish National Dictionary. Designed partly on regional lines and partly on historical principles, and containing all the Scottish words known to be in use or to have been in use since c. 1700. ed. by William Grant and David D. Murison. Volumes I – X. Edinburgh 1929–1976 (the most comprehensive dictionary of Scottish dialects).

- The Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue from the Twelfth Century to the End of the Seventeenth. ed. by William A. Craigie et al. Volumes I – XII. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1931-2002.

- The Concise Scots Dictionary. Managing Editor: Marie Robinson. Aberdeen 1985 / Edinburgh 1996.

Whole Scottish Grammar:

- William Grant, James Main Dixon: Manual of Modern Scots. Cambridge 1921 (detailed, benchmarking overview).

Place grammars:

- Eugen Dieth : A Grammar of The Buchan Dialect (Aberdeenshire). Vol. 1: Phonology - Accidence. Diss. W. Heffer & Sons, Zurich / Cambridge 1932 (to this day the most detailed description of the grammar of a Scottish dialect).

- TA Robertson, John J. Graham: Grammar and Use of the Shetland Dialect. 2nd Edition. The Shetland Times, Lerwick 1952, 1991.

- Paul Wettstein: The Phonology of a Berwickshire Dialect. Student SA, Biel 1942.

- James Wilson: Lowland Scotch as Spoken in the Lower Strathearn District of Perthshire. Oxford University Press, London 1915.

- James Wilson: The Dialect of Robert Burns as Spoken in Central Ayrshire. Oxford University Press, London 1923.

- James Wilson: The Dialects of Central Scotland [Fife and Lothian]. Oxford University Press, London 1926.

- Rudolf Zai: The Phonology of the Morebattle Dialect, East Roxburghshire. Räber & Co., Lucerne 1942.

Textbooks:

- L. Colin Wilson: The Luath Scots Language Learner . Luath Press, Edinburgh 2002.

Web links

- Dialects using the numbers from 1 to 10

- Scots Online

- The Scots Language Dictionary

- The Scots Language Society

- Scots Language Center

- Peter Constantine: Scots: The Auld an Nobill Tung. In: Words Without Borders. 2010, accessed December 17, 2013 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Marc Bloch : The Feudal Society. Berlin 1982, p. 64.

- ^ Hugh Seton-Watson: Nations and States. An Inquiry into the Origin of Nations and the Politics of Nationalism. Boulder, Colorado 1977, p. 30.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, pp. 30-31.