Dictatorship of the proletariat

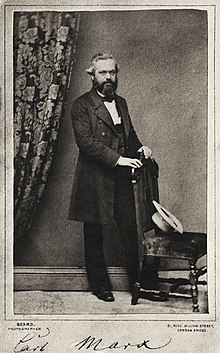

The dictatorship of the proletariat is a term that emerged in the middle of the 19th century to describe the political rule of social groups that were not yet represented in the state, especially the working class . The term was coined by the reception of the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels . It is undisputed that by the dictatorship of the proletariat they understood the rule of the working class as the majority over the minority of expropriated capitalists who were supposed to make the transition from a bourgeois class society to a classless society (according to the assumptions of Marx and Engels, the proletarian revolutions would come first occur in highly industrialized countries.) The question of how this should be done, on the other hand, was the subject of constant controversy, also in view of the historical usage, which did not necessarily presuppose the meaning of “tyranny”. The term “dictatorship of the proletariat” is not used often in Marx's writings. In the reception of the theories of Marx and Engels, however, the term has a prominent position.

Georgi Plekhanov included the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat in the program of the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party towards the end of the 19th century . In the resulting Communist Party of Russia , the term played an important role after the April Theses in 1917. In the period after the October Revolution and during the conditions of the civil war in the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic (see War Communism ), Vladimir Ilyich Lenin's idea of a dictatorship of the proletariat was attempted in principle. After 1925 reinterpreted increasing in its importance, the term was in the Stalinist- dominated Eastern Bloc countries after the Second World War, in addition to the well-pleasing name " socialist democracy rarely used."

In the 1970s, eurocommunist parties distanced themselves from the slogan of the dictatorship of the proletariat, also to differentiate themselves from the real socialist states. The Eurocommunist program rejected the revolutionary model in favor of the perspective of overcoming capitalism within parliamentary democracy.

The term was often wrongly attributed to Louis-Auguste Blanqui , but it is not mentioned in his writings. The concept of a dictatorship of the proletariat, however, was central to Blanquist currents.

On the term "dictatorship of the proletariat"

While the concept of the proletariat was used in a fairly uniform manner, the concept of dictatorship must be examined more closely in order to be able to understand the different understandings of a dictatorship of the proletariat.

proletariat

The proletariat (originally in non-Marxist from the Latin proletarius "belonging to the lowest class of the people") describes the new class of wage earners in the emerging manufactories and factories that emerged with the development of capitalism and industrialization . Marx defines the proletarian as a doubly free wage worker: free from serfdom , that is, in possession of himself and “free” of the means of production that could ensure his survival through work. Marx describes the emergence of this doubly free wage laborer in Das Kapital using the example of England, where on the one hand peasants ' land was taken away in order to create sheep pastures for the new wool manufactories and factories. On the other hand, craftsmen and weavers were no longer competitive due to the more effective machines and were forced to work in the factories through legislation against vagabondism. According to Karl Marx, the proletariat is that social class which, within a capitalist society, has to sell its labor in the form of wage labor in order to survive.

dictatorship

Brief conceptual history

The term "dictatorship" first appeared in connection with the Roman Republic (500-27 BC), in which there was the possibility that the consul appointed a dictator for a limited time, to whom all offices were subordinate. Accordingly, the term was used for a long time to describe a state of emergency of political violence. There is an analogy to martial law, as both represent forms of crisis government within the institutional system. From this origin of the term, today's understanding of the term dictatorship was formed. Today the term dictatorship denotes the rule by a single dictator, a political party, a minority or group of people who appropriates power over a people, monopolizes it and exercises it without restrictions, in contrast to democracy , in which rule of the People go out.

Use of the term around the 19th century

During the French Revolution from 1789 to 1799, the constitutional and legislative assembly - the National Convention - was called a dictatorship by opponents, as was the British Parliament or the Paris Commune of 1871. In the 19th century, the term dictatorship was used in reactionary circles for today's understanding rather democratic forms of government are quite common. The word dictatorship did not yet have its current meaning and cannot be equated with terms such as despotism , tyranny , absolutism or autocracy , nor was it an antithesis to democracy . Historically , a negative use of the term democracy as the tyranny of the many can be traced back to the state theories of Plato or Aristotle , whereby it should be emphasized that they used the term democracy differently than it is used today. The bourgeois revolutions of 1848 were a “tyranny of democracy” or “tyranny of the masses” in reactionary circles. The Spanish diplomat, politician and state philosopher Juan Donoso Cortés (1809–1853), who is now regarded as the political mastermind of modern dictatorships, stated about the English parliament at this time: “Who, gentlemen, has ever seen a more monstrous dictatorship? "

Connection to the early political left

The connection between the term dictatorship and the political left can be traced back to François Noël Babeuf (1760–1797) and his community of equals for the first time . At a time when the concept of the political left was emerging for the first time. Babeuf's companion Filippo Buonarroti (1761–1837) made the approaches of the community public again about 30 years after his death. The revolutionary government, in the form of a dictatorship of a small revolutionary group, should educate the masses to democracy . This concept became defining for the Blanquists of the 1830s and 1840s. For example, Blanqui (1805–1881) stated: “The fact that France is bursting with armed workers is the beginning of socialism.” Wilhelm Weitling (1808–1871) advocated a personal dictatorship, a “ messiah ” would lead the proletarian revolution. In contrast, the use of the term dictatorship is also to be found in the anarchist Bakunin (1814–1876) with his concept of a “secret” or “invisible dictatorship” exercised by secret societies within the anarchy.

Term at the time of the 1848 bourgeois revolutions

Even for the revolutionary bourgeois and moderate left forces like Louis Blanc (1811–1882), the implementation of democracy was associated with a dictatorial moment, as every fundamentally new system of rule must override the laws of the old system and create new ones. Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) stated in the same context: “The right to revolution is the only really 'historical right', the only one on which all modern states without exception are based.” This is what Karl Marx (1818–1883) said ) of a dictatorship, when in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung he advocated a tougher course for the bourgeois forces in Prussia against the old absolutist-feudalist conditions and for democracy: “Every provisional state after a revolution requires a dictatorship, and an energetic dictatorship. We have it Camphausen [note. Prussian Prime Minister in the revolutionary period from March to July 1848] accused from the start that he did not act dictatorially, that he did not immediately smash and remove the remains of the old institutions. ” Lorenz von Stein (1815–1890), the independent, anti-revolutionary Formulated standpoint, developed a theoretical approach that dealt with the class struggle and the concept of dictatorship.

Use of the catchphrase "dictatorship of the proletariat"

The use of the term dictatorship and the dictatorship of the proletariat by Marx and Engels, who understood the latter to mean the rule of the working class, is well documented. In the 1870s the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat was adopted as a political concept by the Blanquist movement of the International Workers 'Association (IAA), but this did not have an influential position within the workers' movement. After Friedrich Engels' death in 1895, the concept of a proletarian dictatorship was discussed for the first time in the Marxist-oriented German social democracy, for example by Kautsky (1854–1938), Bernstein (1850–1932) or Luxemburg (1871–1919). Plekhanov (1856–1918) and above all Lenin (1870–1924) coined the term dictatorship of the proletariat together with the social upheavals in imperial Russia at the beginning of the 20th century. It was included in the party program of the Russian communists and, beginning with the Russian revolutions in 1905 and 1917 until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, it was to be an important term, both for supporters and opponents of the political system, whereby it was used in very different ways .

Meaning in Marxism

Theory in Marx and Engels

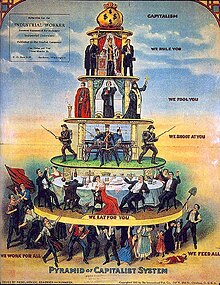

Even if there is no theory of a dictatorship of the proletariat in the original Marxism of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the term can be integrated into a theoretical context. All previous forms of society since the dissolution of the early communist polities are considered class rule by a minority, who controls the means of production of society, over an economically dependent and oppressed majority, so to speak as a dictatorship. The state apparatus is understood as an instrument of power of the economically ruling class, which maintains the exploitative relationship of domination between the classes through its state institutions (see base and superstructure ). Thus, in the Communist Manifesto of 1848, “political violence in the true sense” is understood as the “organized violence of one class to oppress another”, and the state, as Friedrich Engels stated in 1891, as nothing else “as a machine for the oppression of a class by another ”. The bourgeois society with its capitalist production is characterized in this sense, for example, in the text The class struggles in France 1848–1850 as the “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie” with - depending on its organizational forms - varying proportions of political and economic repression. According to Marx, the “dictatorship of the proletariat” or “rule of the working class” constitutes “only the transition to the abolition of all classes and a classless society ”, in which relations of domination become superfluous.

“This socialism is the permanent declaration of the revolution, the class dictatorship of the proletariat as a necessary transit point for the abolition of class differences in general, for the abolition of all relations of production on which they are based, for the abolition of all social relations that correspond to these relations of production, for the overturning of all ideas that arise from them social relationships arise. "

The state, according to Marx a “hideous machine of class rule”, “will not be abolished, it will wither”. Marx justifies this with the concrete social development of the countries of Western Europe. According to Marx, the bourgeoisie “in its barely one hundred years of class rule created more massive and colossal productive forces than all previous generations combined”. “The modern worker, on the other hand, instead of rising with the advancement of industry, sinks deeper and deeper under the conditions of his own class. The worker becomes a pauper, and pauperism develops even faster than population and wealth. ”According to Marx, the immanent laws of capitalist production lead to an expropriation of the direct producers (workers) from the means of production and to a centralization of them in the hands of comparatives few capitalists. "The centralization of the means of production and the socialization of labor [note: division of labor ] [however] reach a point where they become incompatible with their capitalist shell." "What is to be expropriated now is no longer the self-employed worker, but the many workers exploiting capitalist. ”While“ all the earlier classes who conquered power… tried to secure their already acquired position in life by subjecting the whole of society to the conditions of their acquisition ”, the proletarians“ can only conquer the social productive forces by Abolish their own previous mode of appropriation and thus the entire previous mode of appropriation. "Private property is abolished, individual (common) property" on the basis of the achievement of the capitalist era "," cooperation and common ownership of the earth and the means of production produced by labor itself ", Arises. "With the abolition of class differences, all social and political inequality that arises from them automatically disappears," hence the state as a means of class rule.

“In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaved subordination of individuals to the division of labor, so that the opposition between mental and physical labor has also disappeared; after work has become not only a means to life but itself the first necessity of life; After the all-round development of individuals, their productive forces have grown and all the springs of the cooperative wealth flow more fully - only then can the narrow bourgeois legal horizon be completely exceeded and society can write on its banner: everyone according to their abilities, everyone according to their needs! "

Concept development in Marx and Engels

From the beginnings to the 1848 revolutions

During their creative period, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels further developed their idea of the emancipation of man through the abolition of the ruling class society into a domination-free, classless society . Around 1844 Marx first came to the conviction that in order to transform society into a classless one, the proletariat had to take over political or state power. In 1875 he wrote in one of the most famous Marxian quotes about the term “dictatorship of the proletariat”: “Between the capitalist and communist society lies the period of revolutionary transformation of one into the other. This also corresponds to a political transition period whose state cannot be anything other than the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat. ”In contrast to all previous social movements that were“ movements of minorities ”or that took place in the“ interests of minorities ”, the“ proletarian movement ”is [...] the independent movement of the immense majority in the interests of the immense majority. ”For Marx and Engels, the“ rule of the proletariat ”was the goal of every genuine labor movement, as stated in the Communist Manifesto of 1848:“ The next purpose of the communists is the same like that of all other proletarian parties: formation of the proletariat into a class, overthrow of bourgeois rule, conquest of political power by the proletariat. "Engels took the same view 25 years later:" Since every political party aims to conquer rule in the state, so the German Social Democratic Workers' Party necessarily strives i listen to rule, the rule of the working class, that is, a "class rule". Incidentally, every real proletarian party, starting with the English Chartists , has always placed class politics, the organization of the proletariat as an independent political party, as the first condition, and the dictatorship of the proletariat as the next goal of the struggle. "

The Paris Commune and the split in the International Workers' Association

While concrete “revolutionary measures” are still proclaimed in the Communist Manifesto, 25 years later, in a foreword to the German republication of the Manifesto, Marx and Engels say that this section “would be different today in many respects”, also due to the changed social reality. They formulate that “the working class cannot simply take possession of the finished state machine and set it in motion for its own purposes”. In addition to the failed revolutions of 1848, the Paris Commune of 1871 played a decisive role in the re-evaluation . Friedrich Engels declared it to be the dictatorship of the proletariat twenty years later, in 1891: “The German Philistine has recently been terrified again at the word: dictatorship of the proletariat. Well, gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the dictatorship of the proletariat ”. In the process of revolutionary proletarian class rule, state power is not transferred to the class of the proletariat, but the state as an instrument of class rule is abolished. For Marx, the Paris Commune was “a revolution against the state itself”. “It was not a revolution to transfer state power from one faction of the ruling classes to the other, but a revolution to break this hideous machine of class rule itself.” “And what did the commune, the majority of them, do? Blanquists existed? In all of her proclamations to the French in the province, she called on them for a free federation of all French communes with Paris, for a national organization that for the first time should really be created by the nation itself. Precisely the suppressive power of the previous centralized government, army, political police, bureaucracy, which Napoleon created in 1798 and which every new government had since taken over as a welcome tool and used against its opponents, precisely this power should fall everywhere, as it has already fallen in Paris was. "

In the period after the failed Paris Commune in 1871, Marx and Engels analyzed the situation and drew their conclusions. As before, Marx and Engels advocated the attainment of political power by the working class, which for this purpose had to organize itself in workers' parties. Now they advocated it even more decisively, so at their instigation one was established within the International Workers' Association (IAA or later “First International”, London Conference from September 17 to 23, 1871 and The Hague Congress September 2–7, 1872) adopted a resolution formulated by them expressing solidarity with the Paris Commune and emphasizing that "the constitution of the working class as a political party is essential for the triumph of the social revolution and its ultimate goal - the abolition of classes". In addition, the statutes were later supplemented with this point, the constitution of workers' parties and the conquest of political power. Only selected sections were invited by the General Council to the meeting in London called by the General Council. The anarchists, such as Bakunin, were not present at the London conference; they had voted against Marx. This fundamental conflict between Marx and the anarchists ultimately led to the split in the IAA at the Hague Congress in 1872.

The role of violence

Marx and Engels also addressed the role of violence in revolutions, although for them revolutions need not necessarily be combined with violence, as they also found. In Capital , Marx names violence as the "midwife of every old society that gets pregnant with a new one", violence itself is an expression of an economic potency, based on the concept of historical materialism , according to which the development of the economic relations of a society is critical to their development as a whole. In the article “ From Authority ”, Friedrich Engels formulated his idea of social revolutions in contrast to the so-called anti-authoritarian currents within the workers' movement: “Have these gentlemen never seen a revolution? A revolution is certainly the most authoritarian thing there is; it is the act by which part of the population imposes its will on the other part by means of rifles, bayonets and cannons, that is, with the most authoritarian means possible; and the victorious party, if it does not want to have fought in vain, must give endurance to this rule by the horror which its weapons instill in the reactionaries. Would the Paris Commune have lasted for just a single day if it had not used the authority of the armed people against the bourgeoisie? Can't you, on the contrary, blame her for not having made sufficient use of her? "

Form of government of the dictatorship of the proletariat

Marx and Engels emphasized the political participation of the people in order to abolish class antagonisms. According to Marx, the Paris Commune “provided the republic with the basis of genuinely democratic institutions. But neither “cheap government” nor the “true republic” [were] their ultimate goal; both surrendered incidentally and by themselves. ”“ The great social measure of the commune was its own working existence. Their special measures could only indicate the direction in which a government of the people through the people is moving. ”“ Instead of deciding once every three or six years which member of the ruling class the people should represent and crush in parliament, that should General voting rights serve the [...] people, just as individual voting rights serve every other employer to select workers, supervisors and accountants in his business. ”Engels takes the same view in the historically most recent use of the term by Marx and Engels. He also mentions the conditions under which, in his opinion, the rule of the working class is enforceable in the capitalist social formations of Europe towards the end of the 19th century: “If something is certain, it is that our party and the working class can only come to power under the form of the democratic republic. This is even the specific form for the dictatorship of the proletariat, as was the case with the great French revolution. the Paris Commune] has shown. "

About the term "dictatorship"

Marx and Engels used the term in a variety of ways. The small states of Germany were under the "dictatorship of the Bundestag , i. H. Austria and Prussia ”. The Berlin government agreed to a "Franco-Russian dictatorship". The whole of Europe was under the “Moscow dictatorship” or Marx, editorial management in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, was described by Engels as dictatorial. The term “ military dictatorship ”, on the other hand, was most likely used only negatively. The term “dictator” was also used negatively in journalistic work against political opponents, even if they actually had no dictatorial powers, for example against Parnell , Bismarck , Lord Palmerston and others. In general, Marx saw dictatorships in any form of bourgeois rule, including in parliamentary democracies. In 1852, in his Eighteenth Brumaire, he called the Second French Republic, after the suppression of the June uprising in 1848, a “dictatorship of the pure bourgeois republicans”.

Within the labor movement, Marx and Engels dealt with Ferdinand Lassalle and Bakunin in particular, who in their opinion harbored secret aspirations for dictatorship . There was a break with Lassalle after it became known that he was conducting secret negotiations with Bismarck and advocating a “social dictatorship” under the leadership of the crown. With the anarchist Bakunin, there was a split within the International Workers' Association due to fundamental political differences. While Marx declared the conquest of political power to be a duty for the proletariat and advocated a tighter organizational leadership of the revolution (“party of the working class”) under the centralized leadership of the International, Bakunin, according to the ideas of anarchism, was in favor of strict non-domination: the abolition of any state Institution and any form of leadership by a party or class.

On the term "dictatorship of the proletariat"

A “class dictatorship of the proletariat” was first mentioned in writing in 1850 in Marx's work “ The class struggles in France 1848–1850 ” . The term dictatorship of the proletariat was first found in the statute of an organization to which Marx and Engels briefly belonged around 1850. In 1852, in a letter to Joseph Weydemeyer , Marx once again mentioned the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat. There he stated exclusively that "this dictatorship itself only forms the transition to the abolition of all classes and a classless society"; this letter was first published in 1907. During the years 1871–1875, other uses of the term are documented. There the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat was based strongly on the Paris Commune. In published writings, the term reappeared around 1890, powerfully in Marx's posthumously published work by Engels, the “ Critique of the Gotha Program ” from 1875, as well as Engels' introduction to “ The Civil War in France ” . Hal Draper differentiates the use and development of the term in three periods, and Lenin proceeds in a similar way in his work “ State and Revolution ” :

- Documented uses of the term "dictatorship of the proletariat" by Marx and Engels:

1. The post-revolutionary period 1850–1852 after the 48 revolutions

- Marx, "The Class Struggles in France 1848-1850" , three mentions, published January - March 1850 (read)

- Marx, discussion with Lüning, "Neue Deutsche Zeitung" of July 4, 1850, written June 1850 (read)

- Marx, "Letter to Joseph Weydemeyer" , dated March 5, 1852 (read)

- Marx & Engels, Statute of the "World Society of Revolutionary Communists" , April 1850 (read)

2. The post-revolutionary period 1871–1875 after the Paris Commune

- Marx, speech on the 7th anniversary of the IAA, first meeting after the Paris Commune, September 25, 1871 (quote from correspondents) (read)

- Marx, "The political indifferentism" dated January 1873 (read)

- Engels, "On the Housing Question" , Section 3, two mentions, 1872/73 (read)

- Engels, "The Program of the Blanquist Fugitives from the Paris Commune" , June 26, 1874 (read)

- Marx, "Critique of the Gotha Program" , written from April to the beginning of May 1875, published in a small group (read)

3. The reintroduction of the term from 1890 by Engels after Marx's death

- Engels, "Letter to Konrad Schmidt " , dated October 27, 1890 (read)

- "Critique of the Gothaer Program" published in "Die Neue Zeit", No. 18, 1st volume, 1890–1891 (read)

- Engels, Introduction to The Civil War in France by Karl Marx, two mentions, dated March 18, 1891 (read)

- Engels, "On the Critique of the Social Democratic Draft Program 1891" written from 18-29. June 1891 (read)

- Engels, conversation with AM Voden (unsure)

- Total : 13 | Marx: 7 | Engels: 7 | Multiple responses in scriptures calculated individually: 17 | Literal uses of the term in total: 9

- Sources : Journals: 7 ; private letters: 2 ; Reproduced from third: 2 ; Articles of Association: 1 ; Forewords: 1

Interpretations of terms and implementations

In addition to the work of Marx and Engels, Lenin's theoretical approaches and / or the development of the Russian Revolution up to the end of the Soviet Union are pivotal points in the reception and theoretical discussion of the term and the theoretical concept behind it.

Lenin characterized the dictatorship of the proletariat as the direct exercise of power by the masses “a million times more democratic than the most democratic bourgeois democracy” . It would be won in a proletarian revolution and serve as a pillar for the establishment of a socialist society. Immediately before the revolution of 1917, Lenin defined the dictatorship of the proletariat in State and Revolution as a short transition phase until the “state withered away” after the world revolution . In the Russian Revolution, the councils ( soviets ) of workers, peasants and soldiers were in such a situation even for a short time. However, due to the civil war and bad harvests, increasing centralization was carried out, which from 1923 finally served as a springboard for the growing bureaucratic caste under Josef Stalin . In 1918 Lenin wrote in the brochure The Next Tasks of the Soviet Power that the developments in Russia since 1917 strikingly confirm Marx's statements about the necessity of a dictatorship of the proletariat:

"It would be [...] the greatest stupidity and the most senseless utopianism to assume that the transition from capitalism to socialism would be possible without coercion and without dictatorship."

The only alternative to the dictatorship of the proletariat is the " Kornilov dictatorship ". On the one hand, the bourgeoisie would foreseeably continue to try for a long time to reverse the new relations of rule, on the other hand, the chaos caused by the world war is the condition for the success of the socialist revolution. To keep hooligans , speculators and other profiteers of such chaos under control, one needs "time and an iron hand".

Rosa Luxemburg criticized Lenin's understanding of the dictatorship of the proletariat as well as Karl Kautsky's . While Lenin is propagating a dictatorship based on the bourgeois model, Kautsky wants to implement the dictatorship in a bourgeois democracy. For them, both perspectives form poles that are equally distant from the dictatorship of the proletariat, after Luxembourg what is needed is a “socialist democracy ” ( democratic socialism ).

“Yes: dictatorship! But this dictatorship consists in the WAY OF USING DEMOCRACY, not in its ABOLITION, in energetic, determined interventions in the well-earned rights and economic conditions of bourgeois society, without which the socialist upheaval cannot be achieved. "

She understood the dictatorship of the proletariat, according to the origin of the word, as “the dictatorship of the CLASS , not of a party or clique, (...) d. H. in the broadest public, with the most active and unrestrained participation of the popular masses, in unlimited democracy. "

criticism

After Marx's expulsion from the International (1872), Mikhail Bakunin formulated, among other things, his fundamental criticism of the concept of the “dictatorship of the proletariat” and its Marxist representatives in his work “ Statehood and Anarchy ” and contrasted it with his concept of a post-revolutionary society. For him the "dictatorship of the proletariat" is just as much a dictatorship of privileged intellectuals, rule and thus lack of freedom:

“They affirm that only the dictatorship, of course yours, can create the freedom of the people; on the other hand we assert that a dictatorship can have no other aim than only one goal, to perpetuate itself, and that it can only create and nurture slavery in the people who endure it. "

According to Bakunin, the revolution should by no means be the work of a clique of leaders; he countered this idea with a spontaneous and federal concept of the revolution. Bakunin advocated the establishment of revolutionary, anti-state secret societies (“communal dictatorship of the secret organization”), which were supposed to abolish all state institutions and social coercion and prevent the emergence of any new power. After that, the communes would organize themselves on their own (see also anarchism ). Marx and Engels criticized Bakunin's idealistic view as well as his lack of understanding of the need for bureaucratic issues in industrial societies.

The social democratic theorist Karl Kautsky criticized the Soviet Russian practice of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the red terror in his 1921 work From Democracy to State Slavery . It wrongly invokes the Paris Commune of 1871, and above all it is not a class dictatorship, but rather it is “clear and simple, if you take the dictatorship in the traditional sense, as the dictatorship of a government” its transitory character, it was always "only intended as a temporary regime". The unrestricted government of Lenin and the Bolsheviks is permanent, which is why it should be called despotic . In 1922, in his brochure The Proletarian Revolution and Its Program , he analyzed Lenin's reinterpretation of the Marxian concept and its application to Russian pre-industrial society as a degeneration:

“The proletariat has the dictatorship. What does that mean? [...] An unorganized class cannot exercise a dictatorship. […] But the anarchy of this kind of dictatorship forms the basis from which a dictatorship of a different kind grew, that of the Communist Party, which in reality is nothing other than the dictatorship of its leaders. "

Significance in Soviet Marxism

In the Soviet Union (1922–1991) the term the dictatorship of the proletariat was initially used to describe the fact that the proletariat , led by the Communist Party , removed through the state apparatus the conditions that dictated the rule of the minority over the majority. For example, the relations to the production of goods (cf. production relations ). In this sense, this relationship of domination was understood as a democratic and a transition phase. The following is an exemplary formulation of the “dictatorship of the proletariat” by Josef Stalin (1878–1953):

“The party is the fundamental leading force in the system of the dictatorship of the proletariat. […]

1. The authority of the party and the iron discipline in the working class necessary for the dictatorship of the proletariat are not based on fear or the 'unrestricted' rights of the party, but on the trust of the working class in the party, on the support of the party by the working class;

2. The confidence of the working class in the party is not acquired all at once and not through the use of force against the working class, but through lengthy work by the party in the masses, through the correct policy of the party, through the ability of the party to convince the masses of the correctness of their own To convince politics through its own experience of the masses, through the party's ability to secure the support of the working class, to lead the masses of the working class;

3. Without the proper politics of the party, reinforced by the experience of the struggle of the masses, and without the confidence of the working class, there is no real leadership by the party and cannot be;

4. The party and its leadership - if the party enjoys the trust of the class and if its leadership is a real leadership - cannot be opposed to the dictatorship of the proletariat, because without leadership by the party enjoying the trust of the working class ("dictatorship" of the Party) a somewhat firm dictatorship of the proletariat is impossible. "

Since the 1930s, the Soviet Union has refrained from describing itself as the dictatorship of the proletariat in its public discourse. As part of the Comintern's popular front strategy against National Socialism, the term dictatorship was now used with negative connotations, for example in Georgi Dimitrov's well-known definition of fascism from 1935. In 1936, Stalin had a new constitution drawn up that was formally democratic and guaranteed human and civil rights. After this self-interpretation, the Soviet Union was no longer a dictatorship , regardless of the Great Terror that began shortly afterwards . In 1961 Nikita Khrushchev , First Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU , declared that the Soviet Union had changed from a dictatorship of the proletariat to a “general people's state”. The Soviet Constitution of 1977 named the dictatorship of the proletariat only in the past tense as a phase that had to be overcome: After its tasks had been fulfilled, “the Soviet state had become a state of the whole people”.

Meaning in real socialism

During the Cold War , the states of real socialism mostly renounced themselves as the dictatorship of the proletariat, but called themselves people 's democracies . Although the leading role of the socialist or communist party of the working class was constitutionally guaranteed in all of them and this thus held the monopoly of state power, there was formally a multi-party system. Nonetheless, these regimes were and still are described by critics as (party) dictatorships. The Yugoslav regime critic Milovan Djilas attested the people's democracies in 1957 "a constant tendency [...] to transform the oligarchic into a personal dictatorship". The dictatorship of the proletariat was rarely used, and even then only in internal communication. In 1975, for example, Erich Mielke , the GDR's Minister for State Security , described his ministry as a “special organ of the dictatorship of the proletariat”.

Meaning in Maoism

In Maoism , the Marxian idea of a dictatorship of the proletariat initially played no role, since in Mao Zedong's revolutionary theory the transition to socialism was brought about not by one, but by four classes: in addition to the workers, also by the peasants, the urban petty bourgeoisie and the “national Bourgeoisie". The government they formed works, as Mao explained in a speech in 1949, as "a democracy for the people and dictatorship over the reactionaries". Among the latter he counted "lackeys of imperialism [...], the landlord class and the bureaucratic bourgeoisie as well as their representatives, namely the Kuomintang reactionaries and their accomplices". As a result, they were excluded from the “people”; they were not subject to any rights of freedom, rather they had to be put in their place and, if necessary, punished for wrongdoing. After the great leap forward , Mao took over and tightened Lenin's dictatorship theory and emphasized that the dictatorship of the proletariat “had to be maintained for another ten generations.” In January 1975, Mao then led a “campaign to study the theory of the dictatorship of the proletariat” one designed to eliminate the moderates within the CCP who wanted to allow small-scale private production. Through a true dictatorship of the proletariat, Mao wanted to wipe out “the birthmarks” of the old, pre-revolutionary society, the goods and wages system. The campaign ended in September 1975.

Significance in Eurocommunism

In the 1970s, the eurocommunist parties of Italy , Spain and France removed the term of the dictatorship of the proletariat from their party programs. The Eurocommunists denied the international leadership claim of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union ( CPSU ) over the other communist parties and, renouncing the slogan of the “dictatorship of the proletariat”, proclaimed a democratic path to socialism within the pluralistic parliamentary systems of Western Europe. Étienne Balibar (* 1942) criticized the abandonment of the term dictatorship of the proletariat: It was too important within Marxist theory. Grahame Lock outlines the approach in a preface to Balibar's writing as follows:

"No-one and nothing, not even the Congress of a Communist Party, can abolish the dictatorship of the proletariat. That is the most important conclusion of Etienne Balibar's book. The reason is that the dictatorship of the proletariat is not a policy or a strategy involving the establishment of a particular form of government or institutions but, on the contrary, an historical reality. More exactly, it is a reality which has its roots in capitalism itself, and which covers the whole of the transition period to communism, 'the reality of a historical tendency', a tendency which begins to develop within capitalism itself, in struggle against it . It is not 'one possible path of transition to socialism', a path which can or must be 'chosen' under certain historical conditions ... but can be rejected for another, different 'choice', for the 'democratic' path, in politically and industrially 'advanced' Western Europe. It is not a matter of choice, a matter of policy: and it therefore cannot be 'abandoned', any more than the class struggle can be 'abandoned', except in words and at the cost of enormous confusion. "

Meaning in the KPD ban / German constitution protection

KPD ban 1956

The only ban on a communist party in a bourgeois democracy in Europe took place in the Federal Republic of Germany . Following efforts by the West German government under Konrad Adenauer , in 1951 an application was made to the Federal Constitutional Court to determine the unconstitutionality of the KPD , which ended after more than five years with a declaration of unconstitutionality. After a detailed analysis of the theories understood or interpreted as a unit for the process by Marx, Engels, Lenin , and Stalin , it was concluded whether these, as a political basis for action, come into conflict with the constitutional order. The dictatorship of the proletariat played a decisive role in the justification of the judgment, the court stated: “Summarized in one formula ... the social development to be inferred from the doctrine of Marxism-Leninism would be: establishment of a socialist-communist social order on the Paths through the proletarian revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat. ”“ If now… the overall goal of 'socialism-communism on the path through proletarian revolution and dictatorship of the proletariat' is clear and unambiguous as a political guideline, it cannot be derived from the fundamental theory recognize what ideas the KPD has in detail about how the partial goal to be achieved in this way, the achievement of political rule of the working class, is to be achieved in the given state, and how the situation that then initially occurs, the dictatorship of the proletariat, looks in detail. It is therefore a matter of making determinations as to which means, according to the Marxist-Leninist theory, are regarded as indispensable for the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat, which characteristics the state order corresponding to it necessarily exhibits and which functions it must necessarily fulfill. Only these ideas will allow sufficient conclusions to be drawn about the fundamental attitude of the KPD to the free democratic basic order . ”On the basis of the works of Marx, Engels, Lenin and later Stalin, which the KPD lent itself as ideological basis, it was concluded:“ The dictatorship of the proletariat is incompatible with the free democratic order of the Basic Law. Both states are mutually exclusive; it would be inconceivable to uphold the essence of the Basic Law if a state system were established that bore the characteristic features of the dictatorship of the proletariat. ”Although the prohibition is still legally effective, it no longer applies in the case law, which means that parties and Groups that would fall under the ban as a successor organization will be tolerated.

DKP

The German Communist Party waived since its inception, although understanding the tradition of the KPD, the (intermediate) target "dictatorship of the proletariat". Instead, it has developed a strategy to achieve an anti-monopoly democracy , in which, within the framework of existing laws, a transfer of the large corporations into public ownership is to be possible. Antimonopoly democracy is a “period of fundamental transformations” in which the working class and other “democratic forces” jointly have sufficient parliamentary power to assert their interests, also as a starting point for further socialist development. While this concept found approval within the left social democracy ( Stamokap wing), it was and is predominantly rejected by the New Left as “reformist”. Non-socialist political groups and the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, on the other hand, consider this approach to be a purely strategic positioning in order to reduce the risk of a party ban.

Use of the term in the German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution

The term “dictatorship of the proletariat” is currently (2007) still used by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and the state authorities for the protection of the constitution to denote certain anti-constitutional efforts. The protection of the Constitution defines the “commitment to the dictatorship of the proletariat” as left-wing extremist , as well as the “commitment to Marxism-Leninism as a 'scientific' guide to action”, the “commitment to socialist or communist transformation of society by means of a revolutionary overthrow or long-term revolutionary changes "And the" commitment to revolutionary violence as the preferred or, depending on the specific conditions, tactical form of struggle ". According to the definition of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution, left-wing extremist efforts are directed against the "state and social order of the Federal Republic of Germany"; elsewhere, "extremist efforts" are referred to as "activities aimed at eliminating the basic values of free democracy".

See also

Web links

- Literature by and about the dictatorship of the proletariat in the catalog of the German National Library

- Dictatorship of the proletariat - in the Marx lexicon of marx-forum.de

literature

- Étienne Balibar : On the dictatorship of the proletariat. With documents from the 22nd Party Congress of the PCF. VSA, Hamburg 1977, ISBN 3-87975-097-1 ( online ).

- Etienne Balibar: dictatorship of the proletariat. In: Wolfgang Fritz Haug (Ed.): Critical Dictionary of Marxism . Volume 2. Argument-Verlag, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-88619-062-5 , pp. 256-267 ( PDF; 7.0 MB ).

- Theodor Bergmann : dictatorship of the proletariat. In: Wolfgang Fritz Haug (Ed.): Historical-critical dictionary of Marxism . Volume 2. Argument-Verlag, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-88619-432-9 , Sp. 720-727 ( online ).

- Cajo Brendel : Critique of Lenin's theory of revolution. Adcom-Verlag, Braunschweig 1958 ( online ).

- Dictatorship of the proletariat. In: Gertrud Schütz u. a. (Ed.): Small political dictionary. 7th edition. Dietz, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-320-01177-4 , pp. 203-206.

- Karl Diehl : The dictatorship of the proletariat and the council system. 2nd Edition. Fischer, Jena 1924, DNB 572853076 ( online ).

- Hal Draper : The "Dictatorship of the Proletariat" from Marx to Lenin. Monthly Review Press, New York 1987, ISBN 0-85345-726-3 ( online ).

- John Ehrenberg: The Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Marxism's Theory of Socialist Democracy. Routledge, New York 1992, ISBN 0-415-90452-8 .

- Uwe-Jens Heuer : Democracy / dictatorship of the proletariat. In: Wolfgang Fritz Haug (Ed.): Historical-critical dictionary of Marxism . Volume 2. Argument-Verlag, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-88619-432-9 , Sp. 534-551 ( online ).

- Wolfgang Leonhard : dictatorship of the proletariat. In: Claus Dieter Kernig (Hrsg.): Soviet system and democratic society. A comparative encyclopedia. Volume 1. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1966, DNB 458176362 , Sp. 1260-1276.

- Mike Schmeitzner : dictatorship of the proletariat. In: Görres-Gesellschaft (Ed.): Staatslexikon. Law - Economy - Society . Volume 1. 8th edition. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2017, ISBN 3-451-37511-7 , pp. 1420-1424 ( online ).

- Klaus Ziemer : dictatorship of the proletariat. In: Dieter Nohlen , Rainer-Olaf Schultze (Hrsg.): Lexicon of political science. Theories, methods, terms. Volume 1. 3rd edition. Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-54116-X , p. 161.

- Contemporary

- Nikolai Bukharin , Evgeni Preobrazhensky : The ABC of Communism , § 23. The Dictatorship of the Proletariat , 1920 ( online ).

- Friedrich Engels : From Authority , 1873 ( online ).

- Friedrich Engels: Introduction to The Civil War in France by Karl Marx, 1891 ( online ).

- Friedrich Engels: On the criticism of the social democratic draft program 1891 , 1891 ( online ).

- Antonio Gramsci : The State and Socialism , Section 2, 1919 ( online ).

- Antonio Gramsci: The historical function of the city , 1920 ( online ).

- Karl Kautsky : The dictatorship of the proletariat , Vienna 1918 ( online ).

- Karl Korsch , Quintessence of Marxism , Section 5, 1922.

- Karl Korsch: The Paris Commune Uprising 1871 - The Russian Revolution 1926 , 1926 ( online ).

- Vladimir I. Lenin : What to do? , 1902 ( online ).

- Vladimir I. Lenin: State and Revolution . The doctrine of Marxism of the state and the tasks of the proletariat in the revolution. In: Lenin, Werke Vol. 25 ( online ).

- Vladimir I. Lenin: The proletarian revolution and the renegade Kautsky . Reprint, Dietz, Berlin 1980 ( online ).

- Georg Lukács : Lenin , Section I, 1924 ( online ).

- Rosa Luxemburg : Burning Time Issues , II. The Dictatorship of the Proletariat , 1917 ( online ).

- Rosa Luxemburg: On the Russian Revolution , 1918 ( online ).

- Julius Martow : Marx and the State , 1925 ( online ).

- Karl Marx , Friedrich Engels: The Communist Manifesto , 1848 ( online ).

- Karl Marx: The class struggles in France 1848–1850 , 1850 ( online ).

- Karl Marx: Letter to Weydemeyer 1852 ( online ).

- Karl Marx: The Civil War in France , 1871 ( online ).

- Karl Marx: Critique of the Gothaer Program 1875 (first published in 1891) ( online ).

- Anton Pannekoek : The New Blanquism , 1920 ( online ).

- David Rjazanov : The Relations of Marx with Blanqui , 1928 ( online ).

- Clara Zetkin , Memories of Lenin , 1925.

Remarks

-

↑ "incidentally, the ascription of the term 'dictatorship of the proletariat' to Blanqui is a myth industriously copied from book to book by marxologists eager to prove did Marx was a putschist 'Blanquist,' but in fact ALL Authorities on Blanqui's life and works have (sometimes regretfully) announced that the term is not to be found there. "

H. Draper, The 'Dictatorship of the Proletariat' from Marx to Lenin , Chapter 1, Section 1, 1987. ( Read ) - ^ Marx, Engels, The Communist Manifesto , February 1848, MEW4: p.472f.

- ↑ For a detailed account see H. Draper, The 'Dictatorship of the Proletariat' from Marx to Lenin , Chapter 1, Section 3, 1987. ( Read )

- ↑ Juan Donoso Cortés, Speech on the Dictatorship, January 4, 1849

- ^ Louis Auguste Blanqui, April 25, 1851

- ↑ For a more detailed presentation see H. Draper, The 'Dictatorship of the Proletariat' from Marx to Lenin , Chapter 1, Section 2, 1987. ( Read )

- ^ Friedrich Engels, Introduction to Karl Marx '"Class Struggles in France 1848 to 1850", 1895

- ^ Karl Marx, "Neue Rheinische Zeitung" No. 100 of September 12, 1848

- ^ Marx, Engels, The Communist Manifesto , February 1848

- ^ A b c Friedrich Engels, Introduction to The Civil War in France by Karl Marx, March 18, 1891

- ^ Class struggles in France

- ^ Karl Marx, Civil War in France

- ^ Friedrich Engels, The Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science , 1880, MEW 19: 224

- ↑ Karl Marx; Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto , MEW 4: 467

- ↑ Karl Marx; Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto, MEW 4: 473

- ^ A b c Karl Marx: Das Kapital , Vol. I, Seventh Section, MEW 23: 791

- ^ Karl Marx: Das Kapital , Vol. I, Seventh Section, MEW 23: 790

- ↑ a b Karl Marx; Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto, MEW 4: 473

- ^ Karl Marx, Critique of the Gotha Program , MEW 19: 26

- ^ German Historical Museum

- ↑ a b c Karl Marx, marginal glosses on the program of the German Workers' Party in the Critique of the Gotha Program 1875 (first published in 1891)

- ↑ a b c Marx, Engels, The Communist Manifesto , February 1848, MEW4: p.472

- ^ Marx, Engels, The Communist Manifesto , February 1848

- ^ Friedrich Engels, On the Housing Question , 1872/73

- ^ A b K. Marx, F. Engels, Foreword to the Communist Party's Manifesto , German edition 1872. MEW 18, 95f. ( Reading )

- ^ K. Marx, Civil War in France, MEW 17, 336 ( reading ); This text is quoted in the preface.

- ^ Karl Marx, Civil War in France , May 1871.

- ^ KARL MARX, General Statutes of the International Workers' Association, As decided by the London Congress in 1871 (Resolution IX); Art. 7a decided by the Hague Congress in 1872 : “In its struggle against the collective power of the possessing classes, the proletariat can only act as a class if it sees itself as a special political party in contrast to all the old parties formed by the possessing classes constituted. This constitution of the proletariat as a political party is indispensable in order to secure the triumph of the social revolution and its highest aim, the abolition of the classes. The unification of the forces of the working class already achieved through the economic struggle must also serve in the hands of this class as a lever in its struggle against the political power of its exploiters. Since the masters of the land and of capital always use their political privileges to defend and perpetuate their economic monopoly and to subjugate labor, the conquest of political power becomes the great duty of the proletariat. "(" London Conference of the International Workers' Association ", MEW 17, p.422)

- ↑ “We know that one has to take into account the institutions, the customs and the traditions of the different countries, and we do not deny that there are countries like America, England, and if I knew your institutions better I might still be Holland add where the workers can reach their goal in a peaceful way. If this is true, we must also recognize that in most countries on the continent the lever of our revolutions must be violence; it is violence that one must one day appeal to in order to establish the rule of labor. "Marx, speech on the Hague Congress, September 15, 1872 ( read )

- ^ Karl Marx, Das Kapital , 1867

- ^ Friedrich Engels, On Authority , 1872/73

- ^ Karl Marx, The Civil War in France 1871

- ^ Friedrich Engels, On the Critique of the Social Democratic Draft Program 1891 , June 1891

- ↑ Engels, “Revolution and Counterrevolution in Germany” , MEW 8:24

- ↑ “The constitution of the editorial staff was the simple dictatorship of Marx. A large daily paper that has to be ready at a certain hour cannot maintain a consistent position with any other constitution. Here, however, Marx's dictatorship was a matter of course, undisputed, and gladly recognized by all of us. It was primarily his clear vision and his confident demeanor that made the paper the most famous German newspaper of the revolutionary years. ”F. Engels, “ Marx and the 'Neue Rheinische Zeitung' 1848–1849 ” , 1884 ( online ).

- ^ Karl Marx: The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852). In MEW, vol. 8, p. 192, quoted from Ernst Nolte : dictatorship . In: Otto Brunner , Werner Conze and Reinhart Koselleck (eds.): Basic historical concepts . Historical lexicon on political and social language in Germany , Volume 1, Ernst Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1972, p. 917 f.

-

↑ “While the International allowed the working class of the various countries the fullest freedom in their movements and endeavors, it managed at the same time to unite the whole working class and for the first time tangibly to the ruling classes and their governments the cosmopolitan power of the proletariat do. […] Autonomy of the sections, free federation of autonomous groups, anti-authoritarianism, anarchy - these are phrases that are well suited to a “society of 'declassed' without a job and without a way out” (sans carrière, sans issue), a society that is The womb of the International conspired to subject it to a dictatorship kept secret and to impose the program of Mr. Bakunin on it! ”K. Marx, F. Engels, A plot against the International Workers' Association , 1873 ( online ).

“The same men who accuse the General Council of authoritarianism, without ever having been able to point out a single authoritarian act on its part, who speak on every occasion of the autonomy of the sections, of the free federation of groups that make up the General Council accuse the intention of imposing its official and orthodox doctrine on the International and transforming our association into a hierarchically constituted organization - the same men constitute themselves in practice as a secret society with a hierarchical organization and under a regime not only authoritarian but absolutely dictatorial; they trample on every trace of the autonomy of the sections and federations; they strive to impose the personal and orthodox doctrines of M. Bakunin on the International through this secret organization. While they demand that the International be organized from the bottom up, they submit themselves, as members of the Alliance, to the order given to them from the top down. [...] Our statutes recognize only one type of member of the International, with equal rights and duties for all; the alliance divides them into two classes, the initiate and the laity, the latter being destined to be led by the former through an organization the existence of which they are not even aware of. The International demands of its followers that they recognize truth, justice and morality as the basis of their conduct; the alliance imposes mendacity, hypocrisy and deceit on its adepts as its first duty by ordering them to deceive the lay international as to the existence of the secret organization and the motives and purpose of their own words and actions. ”F. Engels , The General Council to All Members of the International Workers' Association , 1872 ( online ). - ↑ “But from this miniature painting you will clearly be convinced how true it is that the working class instinctively feels inclined to dictatorship, when they can justifiably be convinced that it is being exercised in their interest, and how much it is therefore, as I told you recently, you would be inclined to see in the crown the natural bearer of social dictatorship, in contrast to the egoism of bourgeois society, in spite of all republican attitudes - or rather on the basis of them - if the crown on their part could ever decide to take the - admittedly very improbable - step of taking a truly revolutionary and national direction and transforming oneself from a kingship of privileged classes into a social and revolutionary people's kingship! ", F. Lassalle, letter from Lassalle to Bismarck , 8 June 1863 ( online ).

- ^ K. Marx, The Class Struggles in France 1848–1850. 1850, MEW7, 89. ( reading )

- ^ Marx to Weydemeyer March 5, 1852 ( Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe . Division III. Volume 5. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1987, p. 76); K. Marx to Weydemeyer (1852), first published in 1907 by Franz Mehring in Die Neue Zeit No. 31, 25th year, 2nd volume. 1906-107, p. 164. MEW 28, p. 507f. Source ( Read ( Memento from May 20, 2013 on the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ For a detailed description of the development of the term in Marx and Engels see H. Draper, The 'Dictatorship of the Proletariat' from Marx to Lenin, Chapter 1, 1987. ( Read )

- ↑ H. Draper, The 'Dictatorship of the Proletariat' from Marx to Lenin, Chapter 1, Section 8, 1987. ( Read )

- ^ N. Lenin [sic!]: The next tasks of the Soviet power. Frankes Verlag, Leipzig 1920, pp. 27 ff., Quoted in Carl Joachim Friedrich : Diktatur. In: Soviet system and democratic society. A comparative encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Image theory to the dictatorship of the proletariat . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau / Basel / Vienna, Sp. 1253.

- ↑ a b c R. Luxemburg, On the Russian Revolution, 1918, published posthumously in 1922, Chapter 4. ( Read )

- ↑ Theo Stammen , Gisela Riescher , Wilhelm Hofmann (ed.): Major works of political theory (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 379). Kröner, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-520-37901-5 , p. 47.

- ↑ trend-line newspaper, Wolfgang Eckhardt: Mikhail Bakunin Aleksandroviè - A biographical overview, Ausg.7 / 8 2000

-

^ Theo Stammen, Gisela Riescher, Wilhelm Hofmann (eds.): Major works of political theory. Kröner, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-520-37901-5 , p. 48.

see e.g. B. Marx, Konspekt von Bakunin's book “Statehood and Anarchy”, 1875. ( Read ) - ↑ Karl Kautsky: From Democracy to State Slavery, A Confrontation with Trotsky on marxists.org, accessed on August 6, 2017.

- ↑ Ernst Nolte: Dictatorship . In: Otto Brunner, Werner Conze and Reinhart Koselleck (eds.): Basic historical concepts. Historical encyclopedia on political-social language in Germany , Volume 1, Ernst Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1972, p. 919 f.

- ↑ Josef Stalin: On the Questions of Leninism, Chapter 5: Party and Working Class in the System of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat (1926) on mlwerke.de, accessed on August 6, 2017.

- ^ Jan C. Behrends : Dictatorship. Modern tyranny between Leviathan and Behemoth (Version 2.0) . In: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte , December 20, 2016 (accessed August 4, 2017).

- ^ Boris Meissner: Party, State and Nation in the Soviet Union. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, p. 243.

- ↑ Constitution (Basic Law) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics adopted at the 7th session of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR in the 9th legislative period on October 7, 1977 ( memento of June 10, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) on Verassungen.net, accessed on June 6 , 1977 August 2017.

- ↑ Milovan Djilas: The new class. An analysis of the communist system . Kindler, Munich 1957, p. 109; for a description of the GDR as a dictatorship, see, for example, Bernhard Marquardt: The role and importance of ideology, integrative factors and disciplining practices in the state and society of the GDR. Vol. 3. In: Materials of the Enquête Commission “Processing the history and consequences of the SED dictatorship in Germany”. Nomos Verlag, Baden-Baden 1995, pp. 379, 730 u. ö .; Günther Heydemann : The internal politics of the GDR . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2003, p. 57; Hermann Weber : The GDR 1945–1990. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2006, p. 136.

- ^ Jan C. Behrends: Dictatorship. Modern tyranny between Leviathan and Behemoth (Version 2.0) . In: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte , December 20, 2016.

- ↑ Mao Tse-tung: On the dictatorship of the people. On the 28th Anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party (June 30, 1949) on infopartisan.net, accessed August 7, 2017.

- ^ Carl Joachim Friedrich: Dictatorship. In: Soviet system and democratic society. A comparative encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Image theory to the dictatorship of the proletariat . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau / Basel / Vienna, Sp. 1255 f.

- ↑ Willy Kraus: Economic development and social change in the People's Republic of China. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 1979, p. 399 f.

- ^ The French Communist Party was only for a short time oriented towards the Euro-Communist regime.

- ↑ "Of particular importance in the program is the sentence that the KPD is guided in all its activities by the theory of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin." The KPD expresses that it regards the writings and other testimonies of these thinkers and politicians as components of a unified, self-contained teaching and as such makes them the basis of their political thought and action. ” Reasons for the judgment

- ^ Grounds for the judgment, BVerfGE 5, 85 <285>

- ↑ Justification of the judgment, BVerfGE 5, 85 <324>

- ↑ With the de-Stalinization there was a distancing from Stalin

- ↑ Justification of the judgment, BVerfGE 5, 85 <507>

- ↑ Contrary to the judgment of the ban: "It is forbidden to create replacement organizations for the Communist Party of Germany or to continue existing organizations as replacement organizations."

- ↑ The text goes on as follows: in addition, depending on the characteristics of the party or group, recourse to theories of other ideologues such as Stalin, Trotsky, Mao Zedong and others

- ↑ Internet presence of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution: Glossary, term left-wing extremism (2007) ( Memento from November 6, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Internet presence of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution: left-wing extremism work area (2007)

- ↑ Internet presence of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution: FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) (2007) ( Memento of April 25, 2007 in the Internet Archive )