Georgi Dimitrov

Georgi Dimitrov (international transcribed Georgi Dimitrov Mikhailov , Bulgarian Георги Димитров Михайлов * 18th June 1882 in Kowatschewzi in Radomir , † 2. July 1949 in the sanatorium Barvikha in Moscow ) was a Bulgarian politician of the Bulgarian Communist Party and founder of the Dimitrov thesis . From 1935 to 1943 he was Secretary General of the Comintern , from 1946 to 1949 Bulgarian Prime Minister.

Life

Political beginnings

In 1894 he began an apprenticeship in a typesetting shop in Sofia , shortly afterwards he became a member of Bulgaria's first trade union, the Book Printers Union . In 1902 he joined the Social Democratic Labor Party of Bulgaria. At their party congress in July 1903, the revolutionary-Marxist wing split off and gave itself the name Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers' Party - Narrower Socialists (Balgarska Rabotnitscheska Sozialdemokratitscheska Partija - Tesni Socialisti) . Dimitrov joined the narrow socialists in 1904 .

In 1909 he was elected to the Central Committee on the recommendation of party leader Dimitar Blagoew . In 1906 he organized the first mass strike in Bulgaria. During this labor dispute in the area of the state coal mines of Pernik, several thousand miners, railroad workers and workers from other industries went on strike for 35 days. In the same year Dimitrov became secretary of the Central Council of Revolutionary Trade Unions in Bulgaria. Despite repeated persecution, Dimitrov organized numerous labor disputes.

From 1913 to 1923 he was a member of the Bulgarian Parliament. In 1919, against the backdrop of the October Revolution, the narrow socialists changed their name to the Bulgarian Communist Party (BKP) and supported the founding of the Communist III. International .

Bulgarian September uprising and flight

From the elections of March 1920, the Peasant People's League led by Aleksandar Stambolijski emerged as the strongest party with just under 350,000 votes (39%), and the Bulgarian Communist Party as the second strongest party with almost 185,000 votes (20%). However, stable cooperation between the two parties did not materialize. There was increasing resistance to Stambolijski's government and its uncompromising course. Stambolijski was overthrown by his opponents on June 9, 1923 and murdered five days later. Aleksandar Zankow became his successor .

On behalf of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (B) , Dimitrov organized an uprising together with Vasil Kolarow in the autumn of 1923 , which was bloodily suppressed. Dimitrov had to flee abroad with his supporters and was sentenced to death in absentia. He emigrated to Austria and later to the German Empire .

In exile

After the suppression of the uprising, he looked for the reasons for the defeat. Following the point of view that was developing in the communist parties, he identified fascism as the opponent of the uprising , a term that arose from the conflict between the Italian communists and Italian fascism. On the basis of his experiences and Lenin's theory of imperialism, Dimitrov developed a theory of fascism that would become canonical for Marxism-Leninism for decades. So he declared in a speech at the 4th World Congress of the Red Trade Union International in 1928 :

“We have to be absolutely clear that fascism is not a place- or time-bound, temporary phenomenon. It is a whole system of class rule of the bourgeoisie and its dictatorship in the age of imperialism [...] Fascism is a constant and growing danger for the freedom of the proletariat and for the class-bound trade union movement. "

Work in Austria

Georgi Dimitroff was appointed political instructor of the Communist International for the Balkan states from the end of 1923 . To do this, he also stayed in Vienna for many months in the 1920s . Since the factional disputes escalated in the small Communist Party of Austria in 1924, he was unceremoniously appointed by the Executive Committee of the Comintern as its representative in the KPÖ after the 7th party congress in March of that year . Dimitrov acted temporarily under his code name "Oswald" as the de facto chairman of the KPÖ.

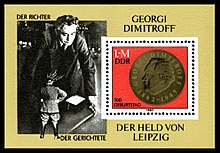

The Reichstag fire trial

On the evening of February 27, 1933, the Reichstag building in Berlin burned down . This gave the National Socialists the opportunity to suspend basic rights in Germany in the so-called Reichstag Fire Ordinance and to arrest numerous opponents, mainly Communists. Dimitrov, who was currently staying illegally in Germany, was arrested on March 9, 1933 in Berlin. He had been assigned a key role in the show trial before the Imperial Court in Leipzig . Besides him, the two Bulgarian communists Blagoi Popow and Wassil Tanew as well as the chairman of the KPD parliamentary group, Ernst Torgler , and the Dutchman Marinus van der Lubbe were also charged. While the prosecutors named 65 witnesses, the witnesses nominated by Dimitrov were rejected and a defense attorney denied. First, the Reichstag fire process in Leipzig was broadcast onto the streets with loudspeakers. However, when Dimitrov, a brilliant rhetorician, succeeded in repeatedly pushing the Prussian Prime Minister Hermann Göring into the role of the accused, the loudspeakers disappeared from the streets.

For the National Socialists, the trial turned into a debacle. No evidence could be produced for the allegations against Dimitrov and the other communist functionaries. Through questions to witnesses such as Goering and Joseph Goebbels , Dimitrov also succeeded in proving that no one in the ruling circles of Germany had really expected an uprising and therefore no measures had been taken to prevent it. The chairman of the court confirmed Dimitrov's sovereignty with the remark: "Abroad, people are of the opinion that you are not in charge of the proceedings, but I!"

In his closing remarks, Dimitrov stated:

“I admit my language is sharp and harsh. My struggle and my life have always been sharp and tough too. But this language is an open and sincere language. I use to call things by their right name. I am not a lawyer who dutifully defends his client here. I defend myself as an accused communist. I defend my own communist, revolutionary honor. I defend my ideas, my communist sentiments. I defend the meaning and content of my life ... "

Since the prosecution also failed to establish a connection between the confessed van der Lubbe and the KPD or Dimitrov, the court acquitted him.

During the trial, the Soviet authorities arrested many of the German airmen in training in the USSR . They were only released after all Bulgarian communists had been allowed to leave for Moscow. By decision of the Soviet government, Dimitrov was granted Soviet citizenship. After his release on February 27, 1934, he was deported to the Soviet Union, where he was given a triumphant reception in Moscow as the "Hero of Leipzig".

Role in the Communist International

As a member of the political secretariat of the Communist International, Dimitrov wrote a self-critical analysis of the Comintern's policy on Germany in 1934, which, with its thesis of social fascism , saw the social democratic parties as the main enemy in the class struggle and thus deepened the division of the working class. This initiated a change in their strategy, which was declared the official line at the VII World Congress of Communist Internationals in August 1935. Now the overwhelming danger of fascism was recognized, under which the National Socialism , which had ruled Germany since January 1933 , was subsumed. The communists should react with a popular front strategy and form alliances with the social democrats.

Dimitrov gave the main speech at the VII World Congress of the Comintern in Moscow, his most famous speech with the title: The Offensive of Fascism and the Tasks of the Communist International in the Struggle for the Unity of the Working Class against Fascism . Here, closely following a resolution of the 13th plenum of the ECCI in December 1933, he defined fascism in power as “the open terrorist dictatorship of the most reactionary, most chauvinist, most imperialist elements of finance capital.” Dimitrov was unanimous at the world congress elected as the new General Secretary of the Comintern.

As general secretary, Dimitrov became Joseph Stalin's loyal vassal . During the Stalinist purges , he responded to the first, still vague, accusations against the Comintern by the secret service chief Jezhov in advance obedience with a request for a "check" of all of its employees. The Comintern had to pay a particularly high blood toll during the Stalinist purges. Dimitrov also accepted the new U-turn in Soviet policy through the German-Soviet nonaggression pact of August 24, 1939, which, according to Dimitrov's diary, Stalin justified on September 7th as an opportunity to incite the capitalist powers against one another.

After the dissolution of the Comintern in June 1943, Dimitrov became deputy head of the International Information Department at the Central Committee of the CPSU . His deputy role was intended to mask the continuity between the Comintern and the new department from the Soviet Union's critical western allies. Internally, Dimitrov was the head of the department. He held this post until his return to Bulgaria in November 1945.

At the end of December 1944 and beginning of 1945, Dimitrov ordered the condemnation of Bulgaria's political, military and intellectual elite to death by the established communist “ people's courts ” from Moscow . They sentenced 2,730 people to death (including high-ranking politicians, the military, publishers and publicists) and 1,305 were sentenced to life sentences.

Prime Minister of Bulgaria

Under his leadership, the Bulgarian Communist Party began to prepare an armed uprising in 1941 during the Second World War . In 1946 Dimitrov became Bulgarian Prime Minister as successor to Kimon Georgiev and General Secretary of the Bulgarian Communist Party. The power of the Communist Party consolidated under his government: the opposition politician Nikola Petkow , chairman of the Agrarian Union, was convicted and executed on charges of planning an overthrow. The constitution of the People's Republic of Bulgaria from 1946, which still contained freedom of the press, assembly and speech, was replaced by a new one that was closely based on that of the USSR.

From 1947 he got closer to the Yugoslav head of state Tito and signed a friendship treaty between the two countries. The aim was a federation between the two countries , to which Dimitrov also publicly invited Romania in 1948 . These plans had been communicated to the Soviet government; she had made no objection. Nevertheless, Stalin ordered Tito and Dimitrov to Moscow on February 10, 1948 and sharply criticized the union plans. The course of the conference was reproduced by Milovan Djilas in his book Conversations with Stalin .

Georgi Dimitroff died on July 2, 1949 in the Barwicha sanatorium near Moscow. His body was embalmed and buried in the center of Sofia in the Georgi Dimitrov mausoleum built in his honor . After the democratization in Bulgaria in 1990, his body was buried in the Central Cemetery (Parcel 22, 42.716678 N, 23.338698 E) in Sofia. The mausoleum was blown up on August 21, 1999.

Honors and personality cult

After his death Dimitrov was venerated in Bulgaria and other socialist countries. In addition to numerous streets, squares and public facilities, the Bulgarian Youth Association was named after him ("Димитровски съюз на народната младеж", German: Dimitroff Association of People's Youth ). Three cities in Bulgaria ( Dimitrovgrad ), Yugoslavia ( Dimitrovgrad ) and the Soviet Union ( Dimitrovgrad ) were named after him. In 1950 the leadership of the BKP set up the order Georgi Dimitrov in his honor . The award was the highest order in the People's Republic.

In Leipzig there was the Georgi-Dimitroff-Museum in the building of the former Reichsgericht from 1952 to 1991 . Also in Leipzig, a thermal power station was named after Dimitrov. The Dimitroffstrasse in Leipzig still bears his name today. In East Berlin , Dimitroffstrasse (today Danziger Strasse) and an underground station were named after him. The historic Augustus Bridge in Dresden bore his name. The soccer and athletics stadium in Erfurt was also named after Dimitroff on November 6, 1948 and carried the name until 1991. Likewise, the Zwickau soccer stadium, which was named Westsachsenstadion after the fall of the Wall . The Untermhausen School in Gera , in which Otto Dix was a pupil from 1899 to 1905, was called Georgi-Dimitroff-Oberschule in GDR times .

The asteroid of the main inner belt (2371) Dimitrov was named after him.

Fonts

- Selected Writings 1933–1945. Rote Fahne publishing house, Cologne 1976, ISBN 3-8106-0014-8 .

- Selected works in two volumes . ("Sozialistische Klassiker" 33/34.) Verlag Marxistische Blätter, Frankfurt am Main 1972.

- About the unions. Verlag Tribüne, Berlin 1974.

- Selected works in three volumes. Verlag Marxistische Blätter, Frankfurt am Main 1976, ISBN 3-88012-266-0 .

- Reichstag fire trial: documents, letters and records. 6th, revised edition. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1978.

- (Ed. By Bernhard H. Bayerlein): Diaries 1933–1943. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-351-02510-6 .

- Against Nazi fascism. Verlag Olga Benario and Herbert Baum, Offenbach 2002, ISBN 3-932636-25-2 .

literature

- Veselin Chadzinikolov: Georgi Dimitroff: Biographical outline. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1972.

- Ernst Fischer : The fanal. The fight of Dimitrov against the arsonists . Verlag "Neues Österreich", newspaper and publishing company, Vienna 1946.

- Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED: History of the international labor movement in data . Globus Verlag, Vienna 1986, ISBN 3-85364-170-3 .

- Rolf Richter: Biographical Epilogue . In: Against fascism and war. Selected speeches and writings . Verlag Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1982.

- Horst Schumacher: The Communist International (1919-1943) . Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-320-01262-2 .

- Historical commission at the Central Committee of the KPÖ: The Communist Party of Austria: Contributions to its history and politics . 2nd Edition. Globus Verlag, Vienna 1989, ISBN 3-85364-189-X .

- Barbara Timmermann: The Fascism Discussion in the Communist International (1920-1935) . Dissertation. Cologne 1977.

- Marietta Stankova: Georgi Dimitrov: A Biography . IBTauris 2010, ISBN 978-1845117283 .

Movies

- 1972: Being an anvil or a hammer (Наковалня или чук, Bulgaria / GDR / Soviet Union, 2 parts, director: Christo Christow )

- 1982: The warning (Предупреждението, Bulgaria / GDR / Soviet Union, director: Juan Antonio Bardem )

Web links

- Literature by and about Georgi Dimitroff in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Georgi Dimitroff in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Georgi Dimitroff in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Texts by Georgi Dimitroff in the Marxists Internet Archive

- Alexander Bahar : The Reichstag Fire Trial, in: Groenewold / Ignor / Koch (Ed.), Lexicon of Political Criminal Trials , last accessed on March 20, 2020

- Works by Georgi Dimitroff in the Gutenberg-DE project

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. Walter Euchner , Helga Grebing , Franz J. Stegmann: History of social ideas in Germany. P. 346.

- ↑ Stella Blagojewa: Georgi Dimitroff - Brief biography. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1954, p. 79.

- ↑ Georgi Dimitroff - Selected works in 2 volumes. Verlag Marxistische Blätter, Frankfurt / Main 1972, Volume 1, p. 70.

- ^ Georgi Dimitroff: Report on the VII. World Congress of the Comintern, August 2, 1935. In: Georgi Dimitroff - Selected works. Foreign language publisher Sofia, 1960, p. 94. (online)

- ↑ В деня за почит към жертвите на комунизма: "И никакви съображения за хуманност".

- ^ Georgi Dimitrov Museum Leipzig . State Archives Leipzig. Retrieved on July 19, 2010 ( Memento from February 20, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Lutz D. Schmadel : Dictionary of Minor Planet Names . Fifth Revised and Enlarged Edition. Ed .: Lutz D. Schmadel. 5th edition. Springer Verlag , Berlin , Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7 , pp. 186 (English, 992 pp., Link.springer.com [ONLINE; accessed on August 5, 2019] Original title: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names . First edition: Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg 1992): “1975 VR 3 . Discovered 1975 Nov. 2 by TM Smirnova at Nauchnyj. "

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Kimon Georgiev |

Prime Minister of Bulgaria 1946 - 1949 |

Wassil Kolarov |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dimitrov, Georgi |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Dimitrov, Georgi Michajlov (full name); Димитров, Георги Михайлов (Bulgarian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Bulgarian politician, communist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 18, 1882 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | at Radomir |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 2, 1949 |

| Place of death | Moscow |