Reichstag fire

The Reichstag fire was the fire in the Reichstag building in Berlin on the night of February 27-28, 1933. The fire was based on arson . Marinus van der Lubbe was arrested at the scene . Until his execution, van der Lubbe insisted that he had set the Reichstag alone on fire. His sole perpetrator already seemed unlikely to many contemporaries and is still controversially discussed. Critics of the single perpetrator thesis suspect that the National Socialists were directly involved.

The political consequences are undisputed. On February 28, 1933, the presidential decree for the protection of the people and the state (Reichstag fire decree) was issued. Thus the basic rights of the Weimar Constitution were de facto suspended and the way was cleared for the legalized persecution of the political opponents of the NSDAP by the police and the SA . The Reichstag Fire Ordinance was a decisive stage in the establishment of the National Socialist dictatorship .

The prisons were soon overcrowded and new prisoners were being added every day. Political prisoners were now held in improvised detention centers. This is how the “wild” (also “early”) concentration camps came into being .

The fire and first political decisions

The social democratic newspaper Vorwärts reported on February 28, 1933 from the day before that in the evening hours a huge fire reddened the sky over the city center and that the dome of the Reichstag was in bright flames. The fire brigade and police unanimously cited arson as the cause, as nests of fire had been found in various places. Shortly after 9 p.m. a fire alarm was given in the Reichstag. First, a fire was reported in the restaurant. There the flames could be extinguished quickly. But shortly afterwards several other sources of fire were discovered. In a short time, the building's conference room burned abundantly. The fire brigade was now on site with 15 fire engines . They took up the fight against the fire with numerous syringes from different sides. However, it was initially impossible to get to the center of the fire because of the heat. Therefore, the fire brigade limited itself to preventing the flames from spreading. It was only around 12:25 a.m. that she extinguished most of the fire. Several thousand onlookers gathered in the course of the extinguishing work. Several hundred groups of the security police carried out barriers, as it was assumed that accomplices could be found among the spectators.

The newspaper also reported that a special commission had been formed in the police headquarters . This had carried out an interrogation of the arrested confessing perpetrator Marinus van der Lubbe. He is 24 years old, a bricklayer by trade and comes from Leiden in the Netherlands . Even when he was first questioned, he maintained that he had acted alone. However, the forward was of the opinion that the perpetrator must have had a good knowledge of the area and indirectly did not rule out complicity on the part of the Communists.

The head of the Prussian political police , Rudolf Diels , who had rushed to the scene immediately after the report, retrospectively reported on the circumstances of the arrest and van der Lubbe's confession. A little later, Adolf Hitler - who was on an election break scheduled from February 26 to 28 -, Joseph Goebbels , Hermann Göring , Wilhelm Frick and probably Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorff also arrived. The presence of Helldorff was witnessed by Hermann Göring in the Reichstag fire trial and, after the war, by Diels, while Helldorff himself testified during the trial that he had not been at the Reichstag. The historian Hans Mommsen notes that either Göring or Helldorff committed perjury . Goering said at the scene:

- “This is the beginning of the communist uprising, they will start now! Not a minute should be missed! "

After this report, Adolf Hitler found even sharper formulations:

- “There is no mercy now; whoever stands in our way will be cut down. The German people will have no understanding for mildness. Every communist functionary is shot wherever he is found. The communist MPs have to be hanged that night. Everything is to be determined what is in league with the communists. There is no longer any protection against social democrats and Reichsbanner either. "

Diels expressed the belief that, according to the police, it was a crazy individual perpetrator. He met with rejection from the leading National Socialists , who urged the declaration of a state of emergency and the arrest of social democratic and communist functionaries .

Political background

The Reichstag fire fell in the middle of the election campaign for the Reichstag election of March 5, 1933 . As the first statements at the scene of the crime showed, even high circles of the NSDAP were convinced that the KPD was attempting to insurrection . Other contemporary observers considered it an action by the new rulers to legitimize planned political reprisals.

The event came - regardless of the real perpetrator - extremely convenient for the National Socialists. The NSDAP's election campaign was already being conducted as a “fight against Marxism ”. The fire now gave the party the opportunity to use force more radically against the left-wing parties using state power.

Immediately afterwards, the NSDAP spoke of a "beacon of bloody riot and civil war". On the night of the fire, Hermann Göring, acting as acting Prussian interior minister, ordered the ban on the communist press. In addition, the party offices were closed and numerous party officials were placed in protective custody. 1,500 members of the KPD were arrested in Berlin alone. Almost the entire parliamentary group in the Reichstag was among them. However, the police did not succeed in arresting the actual party leadership because the Politburo had met for a secret meeting. The party leader of the KPD in the Reichstag, Ernst Torgler , volunteered a short time later in order to counter the allegation that he was involved in the arson .

Since Marinus van der Lubbe , who was arrested at the scene, had allegedly also admitted ties to the SPD , this party also came into the focus of the authorities. The social democratic press, but also the party's election posters, were banned for 14 days.

Formal legalization of political persecution

On February 28, 1933, the Reich Cabinet passed the emergency ordinance “For the protection of the people and the state” . This invalidated the fundamental rights . The police and their auxiliary organs (namely the SA ) were now able to make arrests without giving reasons and to deny those affected any legal protection . Neither the integrity of the apartment nor the property were guaranteed. The postal and telecommunications secrecy was abolished, as was freedom of expression, the press and freedom of association. At the same time, it included greater opportunities for the Reich to intervene in the affairs of the Länder. The death penalty was introduced retrospectively for various terrorist offenses as well as for arson. This regulation was synonymous with the end of the rule of law in its previous form. The ordinance remained in force until the end of the Third Reich and was the basis for a regime of permanent state of emergency .

For tactical reasons, the government refrained from formally banning the KPD. However, on February 28, Adolf Hitler made it unmistakably clear that now “a ruthless confrontation with the KPD is urgently required”. The declared aim was the complete annihilation of the communists. In addition, the emergency ordinance could also be applied to social democrats and ultimately to all opponents of the regime.

The emergency ordinance created the basis for the arrest not only of numerous other functionaries of the workers' parties, but also of numerous critical, mostly left-wing intellectuals. Among them on February 28th were Alfred Apfel , Fritz Ausländer , Rudolf Bernstein , Felix Halle , Max Hodann , Wilhelm Kasper , Egon Erwin Kisch , Hans Litten , Erich Mühsam , Carl von Ossietzky , Wilhelm Pieck , Ludwig Renn , Ernst Schneller , Werner Scholem , and Walter Stoecker . A few days later the police managed to arrest Ernst Thälmann , the chairman of the KPD.

After the fire, the ongoing Reichstag election campaign was steered into openly terrorist channels by the NSDAP. By mid-May 1933, in Prussia alone, over 100,000 political opponents - the majority of them communists - had been arrested and taken to temporary concentration camps and torture rooms . On election day, 69 dead and hundreds were injured, not only on the part of the opposition, but also among the SA and NSDAP.

The Reichstag fire trial

The National Socialist leadership would have liked to forego a proper trial. This was not possible, however, because the dictatorship was only just beginning and was under pressure from abroad, with the KPD in exile playing a strong role. However, one month after the fire in the Reichstag, the government increased the sentence with a Lex van der Lubbe , so that the death penalty could now also be imposed for arson .

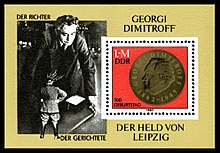

The police investigations and preliminary judicial investigations were directed not only against van der Lubbe but also against the alleged instigator, the German communist Ernst Torgler , and three Bulgarian communists, Georgi Dimitrov , Blagoi Popow and Wassil Tanew . As a state security matter, the case came to the Reichsgericht in Leipzig . A total of over 500 witnesses were heard during the preliminary investigation. The results from 32 volumes of files were summarized in an extensive indictment. The government influenced the process from the start. The judge in charge of the investigation was initially replaced by a man from the regime, who consistently rejected all the accused's requests for exoneration. Dimitrov was constantly handcuffed with iron for five months, causing pain. He even had to write letters to the court and his lawyer in these shackles. The court appointed a lawyer for Dimitrov. Several attempts by Dimitrov to get a lawyer he could trust failed. Dimitrov's first lawyer, Werner Wille, whom Kurt Rosenfeld had mediated before he fled, gave up his mandate; the court rejected other defense lawyers chosen by Dimitrov. This also included foreign lawyers such as human rights lawyer Vincent de Moro-Giafferi .

On September 21, 1933, the trial before the IV Criminal Senate of the Reich Court in Leipzig opened in the Great Hall. The presiding judge was Wilhelm Bünger , a former member of the DVP , state minister in Saxony and not a supporter of the new regime. The negotiations were largely shaped by political disputes. While in custody, Dimitrov had made himself thoroughly familiar with German criminal law and the code of criminal procedure and, as a good rhetorician, fought fierce speeches with representatives of the prosecution, tried to involve the witnesses in contradictions and made a large number of requests for evidence . Due to the numerous domestic and foreign press representatives, he could be sure of his media impact. The judges, critically observed by both the press and the government, turned out to be helpless towards Dimitrov. Her only weapon was his multiple expulsion from the process. It is noteworthy that some witnesses who testified under pressure against the defendants as prisoners in concentration camps recanted their testimony in court. In the course of the trial, an expert came to the conclusion that van der Lubbe could not possibly be the sole perpetrator, but the foreign public in particular remained skeptical. The turnaround was to be brought about by the performances of Goebbels and Göring. Goering sharply attacked the Communists, but let himself be upset by Dimitrov. Goebbels behaved more skilfully, but even he did not succeed in refuting the impression of a National Socialist show trial. From October 10th, 10 days of negotiations began in the room of the budget committee of the largely undamaged Reichstag building itself, which caused the greatest international sensation.

The judgment, against which no appeal was possible, was issued on December 23, 1933. Thereafter, the thesis of a communist conspiracy was upheld, but the accused Torgler, Dimitrov, Popov and Tanew were acquitted for lack of evidence . The defendant van der Lubbe was found guilty of high treason in the act of riotous arson and attempted simple arson and sentenced to death and loss of civil rights under a law passed on March 29, 1933 . The verdict was greeted with relief abroad and with indignation by the National Socialist press. Van der Lubbe was on 10 January 1934, the guillotine executed . The Bulgarians were soon expelled and the other defendants were taken into “protective custody” after the trial . Torgler was not released until 1936.

Although the independence of the court was already severely restricted, the judgment showed that the regime's control over the judiciary was not yet fully secured. The process therefore became a major driving force behind the creation of extraordinary criminal law. Last but not least, this included the establishment of the People's Court .

Before the trial began, an “International Commission of Inquiry into the Reichstag Fire” was set up in London . Denis Nowell Pritt acted as chairman of the board, which is made up of renowned lawyers . Also Willi Münzenberg played an important role, which had begun with the Brown Book a momentous anti-fascist campaign: The Nazis were no longer portrayed as agents of class interests of capital, but as morally depraved criminals. Van der Lubbe was falsely portrayed as the weak-willed “lust boy” of the homosexual SA chief Ernst Röhm . Witnesses for this had not seen him for years, counter-witnesses were not summoned. The commission conducted a counter-trial and announced its verdict immediately before the start of the Leipzig trial. In it, the National Socialists were found guilty and the Communists acquitted. Van der Lubbe was seen as a perpetrator, but it was believed that he had acted on behalf of or with the approval of the National Socialists. This counter-process influenced international public opinion and the Reichsgericht was implicitly forced to refute the results of the counter-process.

consequences

Immediately after the Reichstag fire, the National Socialists began to arrest their political opponents. That same night Goering had ordered, e.g. B. to lock communist members of the Reichstag and Landtag in prisons. The number of inmates increased daily. When the capacity of the prisons was no longer sufficient, regional police authorities and the SA began to keep their prisoners in improvised detention places. Today these improvised places of detention are known as “wild” (also “early”) concentration camps. However, they differ significantly from the later concentration camps, as the latter were systematically structured, based on the Dachau prototype . It was only after the Röhm putsch that Hitler succeeded in ousting the SA, and the SS took control of the regime's now systematically organized concentration camps, which were gradually established.

The Reichstag fire in the judiciary after the war

In 1967, in the retrial, the Berlin Regional Court overturned the judgment against van der Lubbe regarding high treason, but left it in place with regard to arson. In 1980, the process to operate was Robert Kempner , in the Nuremberg trials Deputy Chief Prosecutor Robert H. Jackson and convinced of the innocence van der Lubbe, resumed and van der Lubbe acquitted on all counts, after which the prosecution lodged an appeal. In the last decision of the Federal Court of Justice in 1983, the question of accomplices was expressly left open as irrelevant, as this in any case does not exclude van der Lubbe's involvement in a criminal offense. On the basis of a law from 1998 , the verdict against van der Lubbe was now completely overturned in January 2008 because the death penalty was based on "specifically National Socialist injustices".

The dispute over the perpetrator

There are three theories behind the fire:

- The National Socialists spoke of a “communist uprising”, for which the fire in the Reichstag should have been the beacon. Much of the historical research argues that the National Socialists - initially actually believing in the communist uprising - exploited the opportunity virtuously and presented the suspicion as fact.

- Even after the Reichstag fire, it was suspected that the National Socialists themselves had started the fire in order to have a pretext for the persecution of political opponents and the subsequent " conformity " of the German state. Members of the ruling NSDAP were most likely to have had the opportunity to do so - especially Reichstag President Göring, because a two-meter-high pipeline led from the boiler house in his official palace to the heating center in the basement of the Reichstag.

- Finally, there is the thesis of the sole perpetrator of Marinus van der Lubbe, who was found at the crime scene . According to her, a significant element of the National Socialist expansion of power can ultimately be traced back to a coincidental event that suited the National Socialists.

Evidence of communist insurrection planning was never provided during the Nazi regime and, according to current knowledge, never existed. The Reichstag fire did not take advantage of the communists; on the contrary, it brought about their legalized and state-directed persecution - a project that the National Socialists had always announced before they took office. Van der Lubbe was not in contact with the KPD at the time and - despite failed attempts to emigrate to the Soviet Union - had long since fallen out with the Dutch Communists.

Just two hours after the start of the fire, Willi Frischauer, reporter for the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung , had wired to his newspaper that it was beyond doubt that the fire had "been kindled by mercenaries of the Hitler government" and he mentioned the "apparently" of the arsonists used the underground passage. A brown book published in Paris under the direction of Willi Münzenberg was supposed to prove this thesis. In it, as the American historian Anson Rabinbach writes, communist anti-fascism put forward a counter- conspiracy theory : it was not the communists who conspired to trigger an uprising with the beacon of the Reichstag fire, as the official Nazi propaganda claimed, it was the National Socialists who had one Carried out a well-planned game to destroy democracy in Germany and get their opponents out of the way.

At the beginning of the 1960s, the Lower Saxony constitutional protection officer Fritz Tobias (with reference to Walter Zirpins ), supported by the professional historian Hans Mommsen , questioned this version, which was largely socially accepted at the time, initiated by a series in Spiegel 1959/1960. In the same magazine on January 16, 1957, Paul Karl Schmidt , who was press officer in the Foreign Office during the Nazi era , had already put forward the thesis that van der Lubbe was the sole perpetrator; at times he was in charge of the editing of Fritz Tobias' manuscript for the above-mentioned Reichstag fire series of the Spiegel .

In 1962, Hans Schneider checked Tobias' work on behalf of the Institute for Contemporary History (IfZ) . He assessed some of the evidence as incorrect, proved Tobias tampering with and came to other conclusions, namely that van der Lubbe could not have been the sole culprit. Schneider was unable to finish his work on time. Hans Mommsen, who also worked for the IfZ, suggested preventing publication “for general political reasons” and, if necessary, exerting pressure on Schneider through his superiors in the school service so that he would not publish his opinion elsewhere. The institute management commented on this in 2001 and found that these statements by Hans Mommsen were "completely unacceptable from a scientific point of view". At the same time she stated that Hans Schneider's rough manuscript “was and is not ready for publication”.

Editing would have been sufficient to make Schneider's documentation ready for publication, but the IfZ management wanted to prevent publication at all costs. Why the IfZ, contrary to previous conviction, sided with Tobias, remained open. It is on record that the head of the institute at the time, Krausnick, felt threatened by Tobias, because Tobias "blatantly misused his official possibilities for purely private purposes" to obtain material about the past of a number of people.

An International Committee for Scientific Research into the Causes and Consequences of the Second World War , which was set up in Luxembourg in 1968, also turned against the lone perpetrator thesis. In the 1970s, it submitted documents that were supposed to prove that the National Socialists were responsible. Proponents of the thesis of National Socialist perpetrators such as Walther Hofer , Edouard Calic and Golo Mann also used "popular educational" arguments: If it should turn out that the Reichstag was not set on fire by the National Socialists, the other crimes could also be questioned . However, according to Golo Mann and Walther Hofer, these “popular educational considerations” would not have prevented them from accepting new evidence. He told Fritz Tobias, Mann emphasized, that he would be the first to accept the single perpetrator thesis "if you can prove it".

In an anthology published in 1986, which again presented arguments against the perpetrators of the National Socialists, the Berlin historian Henning Köhler accused the Luxembourg committee of massive falsification of source material, which made the debate highly emotional. The committee's opponents saw their allegations confirmed when its representatives were unable to present original documents to the Federal Archives because they had been destroyed after inspection.

The accusation of forging sources discredited the thesis of the Nazi perpetrators for years. Heinrich August Winkler wrote, for example: "The publications of the International Committee Luxembourg [...] have shown so many forgeries that it is unnecessary to quote them." In large parts of historical scholarship, the thesis of van der Lubbe's sole perpetrator in all doubts has been confirmed in the last Considered the most likely for decades. Winkler said that the arson was almost certainly committed by van der Lubbe, who was arrested at the scene. A diary entry by Joseph Goebbels from April 9, 1941 about a conversation with Hitler, according to which both puzzled over who started the fire, suggests, in the opinion of Klaus Hildebrand , that the National Socialist leadership was surprised by the fire. Hans-Ulrich Wehler is of the opinion that research since 1962 has provided sufficient clarity in favor of van der Lubbe's sole responsibility.

In the last few years, however, doubts have been voiced again from various quarters. Historians, physicists and fire experts denied the possibility that the severely visually impaired van der Lubbe - in January 1933 he had 15 percent vision in the left eye and 20 percent in the right eye - could enter the plenary chamber of the Reichstag alone in twenty minutes and only with Coal lighters could have set fire. The behavior of Hermann Göring and his quick appearance in front of the Reichstag building also indicate a direct responsibility of the National Socialists. Immediately after the fire, both a fire fighter and the chief fire director assumed that no one could have started the fire. Those who doubt van der Lubbe's sole perpetration see their analysis confirmed by the findings of newly brought up sources. The proponents of the single perpetrator thesis, however, consider this line of evidence to be inconsistent and failed.

Hermann Graml admits that the more recent publications have shown “mistakes and erroneous interpretations of earlier work”. He notes that "old suspicions that suggested Nazi perpetrators were refreshed and additional suspicions discovered." However, the details of the course of the fire and the discrepancies shown are not significant enough to be able to provide sufficient evidence of Nazi perpetration. The journalist and historian Sven Felix Kellerhoff claims in his 2008 book on the Reichstag fire that all the details pointed to a smoke gas explosion (referred to by Kellerhoff as a "backdraft") that suddenly set fire to the plenary hall. Kellerhoff sees this as supporting van der Lubbe's thesis of sole perpetrator. This is contradicted by fire experts: “Assuming that this statement is correct,” says Karl Stephan , professor emeritus at the Institute for Technical Thermodynamics and Thermal Process Engineering at the University of Stuttgart, “however, it proves the opposite of what is supposed to be proven Backdraft would be particularly likely if liquid fuels had been introduced into the plenary chamber beforehand. ”This would mean that van der Lubbe would not be a single perpetrator.

The Goebbels biographer Peter Longerich stated in 2010 that the diary entries of the Propaganda Minister made it clear how much the Nazi leadership came in with arson in order to smash the political left, especially the KPD. However, they did not provide any evidence of Nazi perpetrators, nor could this be excluded based on the entries made by the Propaganda Minister. Longerich adds: “The question of the authorship of the Reichstag fire is the subject of a long-standing controversy that has by no means been clarified in favor of the single perpetrator thesis.” The American historian Benjamin Carter Hett poses in his relevant study The Reichstag fire. Retrial found that there was "a high degree of probability ... van der Lubbe was not a lone perpetrator". He had neither the necessary time nor the appropriate means for a successful arson. The circumstantial evidence suggests an incendiary initiated by the National Socialists and carried out by SA members around Hans Georg Gewehr , with the plenary chamber being prepared with self-igniting substances before van der Lubbe carried out his amateurish attempts to set it on fire. Ultimately, however, this hypothesis cannot be proven either. The debate and research are still ongoing.

In 2019, Fritz Tobias's estate contained a copy of an affidavit from SA man Hans-Martin Lennings from 1955, according to which he had gone to the Reichstag on the orders of his superior Karl Ernst Marinus van der Lubbe. Benjamin Carter Hett, for example, regards this statement as a suitable argument against the single perpetrator thesis, subject to closer examination, but Tobias had not mentioned its existence either in his own writings or to historians. Sven Felix Kellerhoff, on the other hand, believes Lennings' portrayal is untrustworthy, as it contradicts the investigation files.

literature

Contemporary publications

- Brown book (I): Brown book about the Reichstag fire and Hitler terror . Frankfurt am Main 1973, ISBN 9783876825007 (reprint of the original edition of the Universum Bücherei, Basel 1933).

- Alfons Sack : The Reichstag Fire Trial . Ullstein, Berlin 1934.

- Braunbuch (II): Dimitrov versus Göring . Cologne / Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-7609-0552-8 (reprint of the original edition of Editions du carrefour, Paris 1934).

- White paper on the shootings of June 30, 1934 , Paris 1934. (with the alleged "Ernst Testament" on responsibility for the Reichstag fire)

Monographs and edited volumes

- Fritz Tobias : The Reichstag Fire - Legend and Reality . Grote, Rastatt 1962.

- Walther Hofer , Edouard Calic , Karl Stephan, Friedrich Zipfel (eds.): The Reichstag fire. A scientific documentation . 2 volumes. Arani, Berlin 1972/1978.

- Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED (ed.): The Reichstag fire process and Georgi Dimitroff . Two volumes. Berlin, Dietz Verlag, 1982 and 1989.

- Uwe Backes / Karl-Heinz Janßen / Eckhard Jesse / Henning Köhler / Hans Mommsen / Fritz Tobias : Reichstag fire - clearing up a historical legend . Piper, Munich and Zurich 1986, ISBN 3-492-03027-0 .

- Walther Hofer, Edouard Calic, Christoph Graf , Friedrich Zipfel: The Reichstag fire - a scientific documentation . Ahriman-Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 1992, ISBN 3-922774-80-6 (revised new edition from 1972/1978).

- Georgi Dimitroff : Diaries . Structure, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-351-02510-6 .

- Alexander Bahar , Wilfried Kugel : The Reichstag fire. How history is made . edition q, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-86124-513-2 .

- Hans Schneider: News from the Reichstag fire - a documentation. A failure of German historiography . Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-8305-0915-4 (with a preface by Iring Fetscher and contributions by Dieter Deiseroth , Hersch Fischler, Wolf-Dieter Narr; published by the Association of German Scientists).

- Dieter Deiseroth (ed.): The Reichstag fire and the trial before the Reichsgericht . Verlagsgesellschaft Tischler, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-922654-65-7 (with contributions by Dieter Deiseroth, Hermann Graml, Ingo Müller, Hersch Fischler, Alexander Bahar, Reinhard Stachwitz).

- Sven Felix Kellerhoff : The Reichstag fire. The career of a criminal case . be.bra Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-89809-078-0 .

- Marcus Giebeler: The controversy over the Reichstag fire. Source problems and historiographical paradigms . Martin Meidenbauer, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-89975-731-6 .

- Alexander Bahar, Wilfried Kugel: The Reichstag fire. Story of a provocation. PapyRossa, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-89438-495-1 .

-

Benjamin Carter Hett : Burning the Reichstag. An investigation into the Third Reich's enduring mystery . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-932232-9 .

- extended German edition: The Reichstag fire. Retrial . Translation from English by Karin Hielscher. Rowohlt, Reinbek (near Hamburg), 2016, 640 pages. ISBN 978-3-498-03029-2 , (Review by Michael Wildt Fataler Reichstag fire - Did a single perpetrator actually give Hitler the dictatorship? In Süddeutsche, edition of September 3, 2016).

Articles in scientific journals

- Richard Wolff: The Reichstag fire in 1933. A research report , in: From Politics and Contemporary History (APUZ), Bonn: Federal Center for Political Education, ISSN 0479-611X , No. B 3/56, January 18, 1956, pp. 25–56.

- Hans Mommsen: The Reichstag fire and its political consequences (PDF; 2.9 MB) In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 12 (1964), issue 4, pp. 351-413.

- Alfred Berndt: On the origin of the Reichstag fire. An investigation into the passage of time (PDF; 724 kB), in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 23 (1975), issue 1, pp. 77–90.

- Ulrich von Hehl: The controversy surrounding the Reichstag fire (PDF; 1.1 MB). In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 36 (1988), issue 2, pp. 259–280.

- Uwe Backes: Striving for objectivity and popular education in Nazi research. The example of the Reichstag fire controversy . In: Uwe Backes / Eckhard Jesse / Rainer Zitelmann (eds.): The shadows of the past. Impulses for the historicization of National Socialism . 1992, ISBN 3-548-33161-0 , pp. 614ff.

- Uwe Gerrens: On the Karl Bonhoeffer report of March 30, 1933 in the Reichstag fire trial, in: Berlin in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Yearbook of the Berlin State Archives 1991, ed. v. Dagmar Unverhau, Berlin: Siedler 1992, pp. 45–116. Digitized

- Alexander Bahar and Wilfried Kugel: The Reichstag fire. New file finds expose Nazi perpetrators , in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft 43, 9, (1995), pp. 823-832. Online here. [1]

- Jürgen Schmädeke , Alexander Bahar and Wilfried Kugel: The Reichstag fire in a new light , here as an online text. , in: Historische Zeitschrift 269 (1999), pp. 603-651.

- Martin Moll: On the historians' controversy about the Reichstag fire, in: Yearbook for Research on the History of the Labor Movement , Issue I / 2003.

- Eckhard Jesse: Reichstag fire and Reichstag fire process . In: Bavarian State Center for Political Education (ed.): The beginnings of brown barbarism . Munich 2004.

- Hersch Fischler: The timing of the Reichstag arson foundation . Corrections to Alfred Berndt's study (PDF; 831 kB), in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 55 (2005), pp. 617–632.

- Wilfried Kugel: Reichstag fire foundation , in: Ossietzky , (1) Eine neue Campaign , 19/2008, pp. 719–722, (2) The Scapegoat , 20/2008, pp. 757–760, (3) Die Täter , 21 / 2008, pp. 802-804.

- Dieter Deiseroth: The Legality Legend. From the Reichstag fire to the Nazi regime , in: Blätter für deutsche und internationale Politik 2/2008, pp. 91-102.

- Dieter Deiseroth: The Reichstag Fire Trial - a constitutional process? , in: Kritische Justiz 42 (2009), pp. 303–316.

- Dieter Deiseroth: Reichstag arson foundation on February 27, 1933 - Who was it? Notes on the ongoing controversy . In: operations . No 201/202 (2013), pp 143-156 ( humanistische-union.de ).

Web links

- Judgment of the Reichsgericht of December 23, 1933 - XII H 42/33 , in: OpinioIuris - The free legal library .

- Kerstin Arnold: The Reichstag fire in 1933 . In: Shoa.de .

- Ansgar Klein, Birgit Böhme (editor): Reichstag fire forum of the Central and State Library Berlin

- Christiane Schulzki-Haddouti : The Reichstag fire . In: Telepolis , February 25, 2006.

- Inflamed. A new controversy about the Reichstag fire , 3sat / Kulturzeit , September 28, 2012. Interview with Lutz Hachmeister .

- Sven Felix Kellerhoff: Fire in the Berlin Reichstag was a welcome arson. With a map of the route of the crime described by van der Lubbe. In: morgenpost.de. Berliner Morgenpost , February 27, 2013, accessed on June 28, 2019.

- Christiane Schulzki-Haddouti: Unpleasant questions. Dispute over the single perpetrator thesis in the Reichstag fire - the Spiegel story viewed critically again . In: M - Menschenmachen Medien , 05/2015.

- Alexander Bahar : The Reichstag Fire Trial, in: Groenewold / Ignor / Koch (Ed.), Lexicon of Political Criminal Trials , last accessed on March 20, 2020.

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Thamer: Beginning of the National Socialist rule. State of emergency . Federal Agency for Civic Education

- ^ Stanislav Zámečník: That was Dachau . Ed. Comité International de Dachau, Luxemburg 2002, p. 18ff.

- ↑ Vorwärts , morning edition of February 28, 1933; For details on the course of the fire, see Sven Felix Kellerhoff: The Reichstag fire. The career of a criminal case . be.bra Verlag, Berlin 2008, pp. 22–37; Alexander Bahar, Wilfried Kugel: The Reichstag fire. Story of a provocation. PapyRossa, Cologne 2013, pp. 54–82.

- ↑ Benjamin Carter Hett: The Reichstag fire. Retrial. Translated from the English by Karin Hielscher. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2016, ISBN 978-3-498-03029-2 , p. 123.

- ↑ Hans Mommsen: The Reichstag fire and its political consequences . In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 12 (1964), issue 4, p. 386, footnote 146 ( ifz-muenchen.de (PDF; 6.9 MB), accessed July 7, 2013.)

- ↑ quoted from Ulrich Thamm, Der Nationalozialismus , Stuttgart, Reclam, 2002, ISBN 3-15-017037-0 , p. 119.

- ↑ quoted from Ulrich Thamm, Der Nationalozialismus , Stuttgart, Reclam, 2002, ISBN 3-15-017037-0 , p. 119.

- ^ Report of the chief of the Prussian political police, Rudolf Diels in retrospect from the year 1949 . On: germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society . Vol. 4: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949 . Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-32264-6 , p. 604.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : The way into the disaster. Workers and the labor movement in the Weimar Republic 1930 to 1933 . Bonn 1990, ISBN 3-8012-0095-7 , pp. 880-883.

- ^ Konrad Repgen, Karl-Heinz Minuth: The Hitler government . Part 1. 1933/34. In: files of the Reich Chancellery . tape 1 . January 30 to August 31, 1933, documents No. 1 to 206. Harald Boldt Verlag, Boppard am Rhein 1983, ISBN 3-7646-1839-6 , No. 32 - Ministerial meeting of February 28, 1933, 11 a.m., p. 128 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Johannes Tuchel : Concentration Camp . Boldt, Boppard am Rhein 1991, p. 97, fn. 209.

- ↑ Winkler: Way in the catastrophe , pp. 881-883. Ludolf Herbst: National Socialist Germany 1933–1945. Unleashing Violence: Racism and War . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1996, p. 64f.

- ^ Cabinet meeting on a necessary change in the law in connection with the fire in the Reichstag (March 7, 1933) . On: germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org.

- ^ G. Dimitroff: Reichstag fire trial: documents. Letters and Notes . Neuer Weg publishing house, Berlin-Ost 1946, p. 30.

- ^ "A reference to the hall in which Dimitrov Göring suffered a defeat, in which there is no doubt that significant history has taken place, is missing" in all historical representations in the Reichstag building. Michael S. Cullen : The Fire . In: Der Tagesspiegel , February 24, 2008, p. S7.

- ↑ Hans-Georg Breydy: The Reichstag Fire Trial in Leipzig 1933 . In: Reichstag Fire Forum of the Central and State Library Berlin

- ↑ Eberhard Kolb: The machinery of terror. On the functioning of the apparatus of repression and persecution in the Nazi regime . In: Karl Dietrich Bracher u. a. (Ed.): National Socialist Dictatorship 1933–1945. A balance sheet . Bonn 1986, ISBN 3-921352-95-9 . P. 280.

- ^ Anson Rabinbach : Staging Antifascism: The Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror . In: New German Critique 103 (2008), pp. 97–126, here pp. 118 ff.

- ↑ Gero Bergmann: The Reichstag Fire Trial , Section E. The trial before the trial . 18th event of the Humboldt Society on January 31, 1996. Marcus Giebeler: The controversy about the Reichstag fire. Source problems and historiographical paradigms . Martin Meidenbauer, Munich 2010, pp. 34–42.

- ^ Stanislav Zámečník: That was Dachau . Ed. Comité International de Dachau, Luxemburg 2002, p. 19.

- ↑ Landgericht Berlin, decision of April 21, 1967, 2 P Aufh 9/66 (126/66).

- ↑ Federal Court of Justice, decision of May 2, 1983, 3 ARs 4/83 - StB 15/83, BGHSt 31, 365.

- ↑ Legal conclusion. After 75 years, the verdict against Marinus van der Lubbe is overturned. Deutschlandfunk January 11, 2008.

- ↑ Peter Koblank: Reichstag Fire Trial 1933 - Legal aftermath , online edition Mythos Elser, 2007

- ↑ Based on a manuscript by Fritz Tobias: "Stand up, van der Lubbe!" The Reichstag fire in 1933 - the story of a legend . In: Der Spiegel . No. 45 , 1959 ( online ).

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: "Give me four years". Hitler and the beginnings of the Third Reich . 2nd revised edition 1999, p. 82.

- ^ Levke Harders: Marinus van der Lubbe. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- ^ Babette Gross : Willi Munzenberg. A political biography , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1967, p. 259 f.

- ^ Wehler, Gesellschaftgeschichte, p. 604.

- ^ Anson Rabinbach: Staging Antifascism: The Brown Book of the Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror . In: New German Critique 103 (2008), pp. 97–126, here p. 102.

- ↑ Hans Mommsen: The Reichstag fire and its political consequences . In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 12th year 1964, issue 4, pp. 351–413 ( PDF ); see also Marcus Giebeler: The controversy over the Reichstag fire. Source problems and historiographical paradigms . Munich 2010, pp. 74-77.

- ↑ Based on a manuscript by Fritz Tobias: "Stand up, van der Lubbe!" The Reichstag fire in 1933 - the story of a legend . In: Der Spiegel . No. 1 , 1960 ( online - issue 43/1959 to issue 1/1960).

- ^ Wigbert Benz: Paul Carell. Ribbentrop's press officer Paul Karl Schmidt before and after 1945 . Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, Berlin 2005, pp. 72-75, ISBN 3-86573-068-X . Wigbert Benz: Paul Karl Schmidt alias Paul Carell and the implementation of the sole perpetrator thesis at SPIEGEL . In: Reichstag Fire Forum of the ZLB, 2006.

- ↑ On the controversy surrounding the Reichstag fire. In: In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 49, 2001, p. 555.

- ↑ Hans Schneider: News from the Reichstag fire? A documentation . Berlin 2004, p. 51.

- ^ Walther Hofer , Edouard Calic, Karl Stephan, Friedrich Zipfel (eds.): The Reichstag fire. A scientific documentation , Vol. 1, Berlin 1972. Walther Hofer, Edouard Calic, Christoph Graf , Karl Stephan, Friedrich Zipfel (eds.): The Reichstag fire. A scientific documentation , Vol. 2, Munich 1978.

- ↑ after Jasper 1986, p. 132.

- ↑ Marcus Giebeler: The controversy over the Reichstag fire. Source problems and historiographical paradigms . Munich 2010, p. 275 f.

- ↑ Henning Köhler, The "documentary part" of the "documentation" - forgeries on the running belt . In: Uwe Backes, Karl-Heinz Janßen, Eckhard Jesse, Henning Köhler, Hans Mommsen, Fritz Tobias: Reichstag fire - clearing up a historical legend . Piper, 1986, pp. 167-216.

- ↑ On the controversy from the point of view of the critics of the Luxembourg Committee: Peter Haungs: What is wrong with the German historians? Or: is falsification of sources a trivial offense. On the controversy surrounding the Reichstag fire . In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft , issue 4/1986, pp. 535–541. Eckhard Jesse: The controversy about the Reichstag fire - a never-ending science scandal . In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft , issue 4/1988, pp. 513–533.

- ↑ Winkler: Way into the disaster . P. 880.

- ↑ Winkler: Weg in die Katastrophe , p. 880.

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand: The Third Reich . = Oldenbourg ground plan of history , Volume 17, 5th edition Munich 1995, p. 300. Joseph Goebbels: Diaries 1924–1945 , ed. v. Ralf Georg Reuth, Volume 4, Piper Verlag, Munich / Zurich 1992, p. 1559.

- ↑ Wehler: Social History , Vol. 4, p. 604.

- ↑ Benjamin Carter Hett: The Reichstag fire. Retrial. Translated from the English by Karin Hielscher. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2016, ISBN 978-3-498-03029-2 , p. 144.

- ↑ Alexander Bahar, Wilfried ball: The Reichstag fire. How history is made . edition q, Berlin 2001. Reichstag Fire Forum. Wigbert Benz: Book review Dieter Deiseroth (ed.): The Reichstag fire and the trial before the Reichsgericht . Berlin 2006. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , April 16, 2007

- ↑ Henning Köhler: Until the beams bend. A failed attempt to prove that the National Socialists were guilty of the Reichstag fire . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , February 22, 2001; Review by Hans Mommsen in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft 49, 2001, pp. 352–357.

- ^ Hermann Graml in: Dieter Deiseroth (Ed.): The Reichstag fire and the trial before the Reichsgericht . Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-922654-65-7 , pp. 28f.

- ^ Sven Felix Kellerhoff: The Reichstag fire. The career of a criminal case . be.bra Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 3-89809-078-7 , pp. 136-139.

- ↑ Quoted from Walther Hofer, Alexander Bahar: Zauberformeln und Nebelkerzen . In: Friday , No. 9 of February 29, 2008.

- ^ Peter Longerich: Goebbels. Biography . Siedler, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-88680-887-8 , p. 214 f.

- ^ Peter Longerich: Goebbels. Biography , p. 750, note 32.

- ↑ Benjamin Carter Hett: The Reichstag fire. Retrial. Translated from the English by Karin Hielscher. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2016, ISBN 978-3-498-03029-2 , p. 513.

- ^ Benjamin Carter Hett: Burning the Reichstag. An investigation into the Third Reich's enduring mystery . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, pp. 318ff.

- ↑ Wolfram Pyta : Did the SA act on its own? (Review of Benjamin Carter Hett: Der Reichstagbrand. Resumption of proceedings. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 2016). In: FAZ of August 8, 2016, accessed on the same day.

- ↑ Conrad von Meding: Who was the real arsonist? . In: HAZ , July 26, 2019, pp. 2–3. With the four-page affidavit from Lennings

- ↑ Interview with Benjamin Carter Hett, HAZ, July 26, 2019, p. 3.

- ↑ Sven Felix Kellerhoff: What the new affidavit of an SA man means . welt.de , July 26, 2019.