Willi Munzenberg

Willi Munzenberg , origin. Wilhelm Munzenberg, (born August 14, 1889 in Erfurt , † June 1940 in Saint-Marcellin , Isère Département , France ) was a German communist , publisher and film producer . With the New German Publishing House , its newspapers Welt am Abend , Berlin am Morgen and above all the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung (AIZ), Münzenberg was one of the most influential representatives of the KPD in the Weimar Republic . Above all, his work against the colonialism of the European powers is significant . He turned away from the official party line after 1937 and was expelled from the party.

Life

From the village school to the Communist Youth International

Munzenberg was the son of a village innkeeper and grandson of a Baron von Seckendorff . He attended the village schools in Friemar and Eberstädt irregularly and the elementary school in Gotha for a year until 1904 . After a broken apprenticeship as a barber , he worked unskilled in shoe factories in Erfurt from 1904 to 1910.

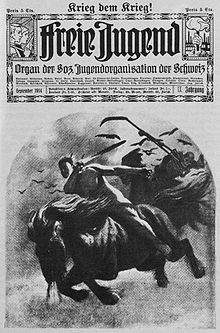

In 1906, Munzenberg joined a workers' education association called Propaganda , became chairman after just under a year and joined the North German Youth Association under the new name of Freie Jugend Erfurt . After he had become an agitator, no Erfurt company wanted to give him any more work; months as a journeyman followed . From August 1910 to the end of 1913 he worked as an assistant in a pharmacy in Zurich . There he joined a group of the socialist youth organization in Switzerland and dealt intensively with the literature common in anarchist circles, such as the mutual aid by Pjotr Kropotkin , The Only One and His Property by Max Stirner or the propaganda of the deed by Johann Most . At the end of July 1912 he became a member of the central board of the socialist youth organization in Switzerland and editor of the monthly magazine Die Freie Jugend . During the First World War he headed the international youth secretariat in Bern and met Lenin . After a stay in prison, Munzenberg was expelled from Switzerland on November 10, 1918 as an "unpopular foreigner" and "supporter of the October Revolution ". He joined the Spartakusbund in Berlin and was a founding member of the KPD. In 1919 he became chairman of the Communist Youth International (KJI).

In the service of Lenin and Stalin

In 1921, Munzenberg was deposed as secretary of the KJI by Grigori Zinoviev , but what happened now was what later gave him a special position in the Comintern and the KPD and which was the reason for his extensive independence: Lenin gave him the very private commission to organize International Workers Aid (IAH ) for the Soviet Union . For this purpose, Munzenberg founded the Illustrierte Sowjetrussland im Bild , which became the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung in 1926 . In 1924 he took over the Neue Deutsche Verlag from Felix Halle for the IAH. His partner Babette Gross became the director of this publishing house . From 1924 to 1933 Munzenberg belonged to the central committee of the KPD and as a member of the Reichstag . From 1925 on he brought about the League against Imperialism , the greatest success of which was an international congress in Brussels in 1927 .

From Stalin , whom he met three times in person, Munzenberg was required to deny himself when he asked the KPD in July 1931 to support a referendum initiated by the Stahlhelm to dissolve the Prussian state parliament . With the referendum, Stahlhelm, NSDAP and other right-wing parties wanted to bring down the SPD government in Prussia . Initially ignoring the referendum, the KPD suddenly had to adopt it as the “Red Referendum” by Moscow orders.

Stalin's intention to physically exterminate the old Bolsheviks was revealed to Munzenberg after reports of the " Great Terror " and the first show trial. His final, dangerous trip to Moscow, which he undertook anyway, was due to the responsibility he had assumed as a proven organizer after the outbreak of the Spanish civil war .

The "Münzenberg Group"

He was "Head of Propaganda for the Communist International for the Western World" and built up the second largest media company of the Weimar Republic after the German national Hugenberg Group , which included the high-circulation newspapers Welt am Abend , Berlin am Morgen and above all the Arbeiter Illustrated newspaper (AIZ) belonged. The Eulenspiegel also had its roots here. As head of production, he also shaped the programs of the two proletarian film companies Prometheus Film and Filmkartell Weltfilm GmbH . The lifestyle he developed was by no means “proletarian”. In 1927 he and Gross moved into a comfortable apartment in the Magnus Hirschfeld house In den Zelten 9a . Unlike most communist officials, he had a car bought for his office, most recently a huge Lincoln limousine . This earned him the title "red millionaire" without actually ever being a millionaire.

After Hitler von Hindenburg had been appointed Chancellor, Munzenberg and Social Democrats organized the conference Das Freie Wort on February 19, 1933 in the ballroom of the Berlin Kroll Opera , in which Ferdinand Tönnies also took part , along with many other great intellectuals . Erich Everth made a fiery plea for maintaining freedom of the press . Among the greetings addresses read out were statements by Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann . Munzenberg himself had to emigrate to Paris immediately after the Reichstag fire, as one of the most wanted communists . In August 1933, the law on the revocation of naturalizations and the deprivation of German citizenship revoked his German citizenship, and his name appeared on the first expatriation list of the German Reich published on August 25th . All newspapers, magazines and their publishers and a book club ( Universum Bücherei ) published by the IAH were banned as early as 1933. The AIZ and Our Time continued to appear abroad.

Activities in exile

A success in the Reichstag fire process , the “Battle for Dimitrov ”, was now urgent , with the most trusted employee, Otto Katz , coordinating the work and research .

The first Brown Book published in this context in 1933 was presented on August 1, 1933 at an internationally acclaimed press conference. The Reichstag fire trial , however only began on 21 September 1933. The book was titled Brown Book of Reichstag Fire and Hitler Terror in Paris with a foreword by the British Labor politician Lord Marley and first under the title Livre brun sur l'incendie du Reichstag et la terreur hitlérienne at Editions du Carrefour in Paris. The editor was Alexander Abusch together with Albert Norden . The publishing house was founded by the German Comintern member Munzenberg. Under this publisher z. B. 1934 also entry banned by Egon Erwin Kisch .

Entry into the office of the Braunbuch authors was permitted without restriction for those eager to work; Munzenberg “knew no fear of spies like the functionaries, who only let subordinates interrogate every newcomer”.

After the Nazi purges (massacre) mid-1934 for the alleged Rohm putsch Münzenberg was a Blue Book print that in a few pages a memorandum of opposition parties to Reich President von Hindenburg contained, was proposed in him, the Hitler government through a presidential board of directors to replace . The Blue Book also contained a white paper on the shootings of June 30th . To camouflage it, it was published under the title Englische Grammatik with the publisher's name “Leipzig”.

On the basis of an initiative of numerous intellectuals (in addition to Münzenberg, among others, Clara Zetkin , Henri Barbusse , John Dos Passos ), a German Aid Committee was founded at the Central Committee of the IAH. The task was the organization and implementation of meetings, rallies and demonstrations for the victims of fascism and the support of the revolutionary struggle of the German working class, charity as the basis of political action. This technique, which he has retained since the IAH was founded, soon allowed the “auxiliary committee” to grow into companies “that had little or nothing to do with the original philanthropic purpose.” A propaganda instrument that he perfected in this context was the so-called “signature stampiglie” “Intellectuals should make their point of view clear to the radical fighters with their signature. When it was imperative to win one of them, the trick used was almost always to

“To convince him that he was needed in the great and so difficult struggle: him as a guarantor for the good cause; for the action that was just necessary to save human lives, to counteract delusion in the face of the growing danger for peace and freedom, and finally to arouse the indifferent. If the appeal came from him, the generally esteemed, admired man, it would arouse the hesitant. "

Munzenberg then ranked the importance: A General Paul Emile Pouderoux's trip to the USA could easily be paid for three thousand dollars, but when asked for support for an event to mark the anniversary of the book burning, he replied: “300 Frcs. , that is out of the question. "The disappointed employee nevertheless stated:

“He's a great stimulator. No implementer. In his own way he is still the best man on the line that I have met so far - stop, no: with the exception of Kurt [Funk- Wehner ]. "

Coinsberg had started to agitate for an alliance in the resistance against National Socialism relatively soon . In September 1935 he succeeded for the first time in bringing together 51 communist, social democratic and bourgeois opponents of Hitler. After its meeting place, this core of a German popular front became known as the Lutetia district . Munzenberg's activity was so uncomfortable that the Nazis sentenced him to death in absentia that same year.

Munzenberg founded the magazine Die Zukunft in 1938 together with Arthur Koestler . Heinrich Mann , a friend, wrote for the first issue in late 1938. In the 10th issue of the future from March 1939, Willi Munzenberg continued to advocate the united front against fascism in the article “Everything for Unity”. On this magazine worked u. a. Lion Feuchtwanger , Oskar Maria Graf , Alfred Döblin and Thomas Mann. Instead of Editions du Carrefour, he used the Sebastian Brant publishing house to publish the magazine and anti-fascist literature.

Development to apostate

Since the Comintern no longer tolerated cooperation with the social democracy from 1928 and not only separated itself from it, but fought it as an enemy, the social-fascism thesis with the slogan of the struggle "class against class" had been propagated by Munzenberg. Accordingly, in the Doriot - Thorez crisis in the spring of 1934, he still took sides for Thorez and against popular front ideas. He documented his commitment in a letter to Moscow with the headline: "How the magazine Our Time fought against Social Democracy and the Second International." It was only when the Comintern's VII World Congress in the summer of 1935 that the tactical realignment came about Munzenberg too, but now immediately as a negotiator with SOPADE . Although he had visible success with the Lutetia circle, he was unable to give its publications a communist character, and criticism was voiced by the KPD. Conversely, in a conversation with the Prague SOPADE board in February 1936, Munzenberg announced his reservations about the Popular Front tactics at KPD headquarters, unfortunately in the presence of the journalist Georg Bernhard , who passed the information on Heinrich Mann on to Moscow, a serious event at the Way to Munzenberg's expulsion from the party.

In 1936, Munzenberg cautiously criticized the Moscow trial against Zinoviev, Kamenev and others. a., which was held in the course of Stalin's policy of purges. After being summoned to the International Control Commission (IKK), which Stalin had founded shortly before to clean up the Comintern apparatus, he avoided any further trip to Moscow, while Walter Ulbricht urged him to do so several times. Munzenberg had been an active member of the Popular Front Committee until the spring of 1937. Walter Ulbricht and Paul Merker had replaced him in the committee in May 1937. In the autumn of 1937 "investigative proceedings" were initiated against him. The burgeoning rumors about Munzenberg's conflict with the Comintern caused great media excitement. For the first time on August 2, 1937, Wilhelm Pieck formulated to Georgi Dimitrov that “Pieck, Dengel , Florin , Kunert and Müller” decided to “ propose to the EKKI secretariat that Willi Münzenberg be excluded from the KPD ... if he did not upon repeated request until August 15 in Moscow. ” Accused of Trotskyism by Walter Ulbricht in 1937 and observed by the secret service for a long time, he was expelled from the Central Committee of the KPD in 1938 - but this never happened in the context of a regular Central Committee meeting and by no Central Committee majority , thus contrary to the statutes. The reason was u. a. Munzenberg's lack of party discipline was used. As a result, and in order to forestall his expulsion from the KPD, Munzenberg himself declared his resignation from the KPD in March 1939, which was announced on March 10, 1939 in his weekly newspaper Die Zukunft / Ein neue Deutschland: Ein neue Deutschland: Ein neue Europe! was reprinted. Munzenberg founded a new party called Friends of Socialist Unity in 1939 .

Mysterious ending

After the Wehrmacht invaded the Benelux countries on May 10, 1940, Munzenberg was interned in the Stade de Colombes camp in the hope of being transported to southern France. In fact, he and other German emigrants were transferred to the Chambaran camp south-east of Lyon. After the internees had convinced the French camp commandant to leave the area threatened by the German advance on the Plateau de Chambaran, Munzenberg left the column on June 21, 1940 near Charmes . According to information from companions, including Leopold Schwarzschild , Kurt Wolff , Paul Westheim and Clement Korthum , he hoped to be able to make his way to Marseille more quickly on his own , where he could easily go underground and perhaps find a ship to North Africa. The traceable route, however, suggests the destination Switzerland, where he and Gross had good friends and money in the bank. His body was found on October 17, 1940, with a string tied around his neck. He probably died around June 21 or 22, 1940 in the “Le Caugnet” forest near the village of Montagne (Isère) near Saint-Marcellin .

Since the 1950s and 1960s, various authors have speculated that Willi Munzenberg was the victim of a Stalinist-motivated murder. This was contradicted in other treatises, some of which cite newly found documents of the (investigation protocol of the national gendarmerie , which suggested suicide as a result). The historian Reinhard Müller (sociologist, 1944) came in 1997 in his contribution about Munzenberg in the book Democratic Ways. German résumés from five centuries came to the conclusion that the mystery of Munzenberg's death (suicide, murder by Gestapo or NKVD agents) has still not been solved.

The role of Munzenberg

Munzenberg played an outstanding role in the success of the KPD in the Weimar Republic. Thanks to his privately held press products, he was able to reach a wider audience than the press directly linked to the KPD. Politically, they had the same line as the latter, but were closer to the thoughts and interests of the workers, which was also expressed in the article profile. They were not as theoretical and doctrinal as the press directly linked to the KPD. He came up with this during his time as the organizer of the IAH. Margarete Buber-Neumann , Munzenberg's sister-in-law, wrote:

“In this activity, Munzenberg was the first communist to understand the power represented by the intellectuals sympathizing with the communist parties. From then on he turned his most essential propaganda activity to them. He threw the doctrinal workings of the Communist Party leadership, its inedible, wooden dogma language overboard and found the right expression and the appropriate methods to rally sympathetic intellectuals in a broad periphery around the Communist Party. "

Munzenberg's work was characterized by an openness in which there was also room for the discussion with the sympathetic intellectuals, which contributed to the fact that the KPD was integrated into the discourse framework of the Weimar Republic. This can be seen in the diverse employees of the AIZ . A frequently mentioned addressee of Munzenberg's media, the proletariat, could not be won "spiritually". When asked whether “the campaigns were idle” in Paris, since they could neither prevent the war nor disempower Hitler, the answer remains that they contributed “to the awareness of the moral foundation of the anti-Hitler coalition in good time many people could penetrate ”.

research

The Willi-Munzenberg-Forum deals with research into the life and work of Munzenberg; This was also done by a European workshop on this topic in autumn 2012 and the 1st International Willi Munzenberg Congress in Berlin from September 17 to 20, 2015. The contributions are documented in the volume Global Spaces for Radical Transnational Solidarity, which was published online in 2018 . Contributions to the First International Willi Munzenberg Congress 2015 in Berlin .

Trivia

The large event hall in the Neues Deutschland publishing house in Berlin-Friedrichshain is named after him as the "Münzenbergsaal".

Fonts

- The struggle and victory of the Bolsheviks. Social Democratic Youth Organization in Switzerland, Zurich 1918 ( digitized version of the 3rd edition, Stuttgart 1919)

- The Socialist Youth International . Foreword by Clara Zetkin , Verlag Junge Garde, Berlin 1919.

- Conquer the movie! Waving from practice for the practice of proletarian film propaganda. New German publishing house, Berlin 1925.

- Five years of international workers' aid. New German publishing house, Berlin 1926.

- The third front. Records from 15 years of the proletarian youth movement . Foreword by Fritz Brupbacher , Neuer Deutscher Verlag, Berlin 1930. (Reprints: Berlin 1978, Winterthur 2015)

- Solidarity. Ten years of international workers' aid 1921–1931. New German publishing house, Berlin 1931.

- White book on the shootings of June 30, 1934. Paris 1934. (published anonymously)

- Propaganda as a weapon. Carrefour, Paris 1937.

- CV [1918]. Publishing house Detlef Aufermann, Glashütten im Taunus 1972.

- Propaganda as a weapon. Selected Writings 1919–1940. Edited by Til Schulz, March publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1972. Schröder. March publishing house, Frankfurt a. M. 1972.

literature

Literature overviews and bibliographies

- Bernhard H. Bayerlein, Kasper Braskén, Uwe Sonnenberg, Gleb J. Albert: Research on Willi Münzenberg (1889-1940). Life, Activities, and Solidarity Networks. A Bibliography. In: International Newsletter of Communist Studies Online. Vol. 18 (2012), No. 25, pp. 104-122. (PDF; 2.7 MB).

Biographies and Biographical Articles

- Kurt Kersten : The end of Willi Münzenberg. A victim of Stalin and Ulbricht. In: Deutsche Rundschau . Volume 5, 1957, pp. 484-499.

- Babette Gross : Willi Munzenberg. A political biography. (= Series of the quarterly books for contemporary history. No. 14/15). German publishing house, Stuttgart 1967.

- K. Haferkorn: Munzenberg, Wilhelm. In: Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED : History of the German Workers' Movement . Biographical Lexicon. Dietz Verlag , Berlin 1970, p. 340 ff.

- Siegfried Bahne: Willi Münzenberg (1889–1940). In: Heinz-Dietrich Fischer (Ed.): German press publishers from the 18th to the 20th century. Verlag Documentation, Pullach near Munich 1975, ISBN 3-7940-3604-4 , pp. 336–347.

- Gerhard Paul: The betrayed socialist. How difficult it is for a communist to part with his party . In: Die Zeit , No. 27/1990.

- Gerhard Paul : [sic] learning process with a fatal outcome. Willi Munzenberg's turning away from Stalinism. In: Exile Research. An international yearbook. Volume 8, 1990, pp. 9-28.

- Harald Wessel : Munzenberg's End. A German communist in the resistance against Hitler and Stalin. The years 1933 to 1940 . Dietz, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-320-01743-8 . (Critical review by Gerhard Paul in Die Zeit 1991 under the title: Tödlicher Lernprozess. About the background of Willi Munzenberg's suicide? A turning history. )

- Tania Schlie, Simone Roche: Willi Münzenberg (1889-1940). A German communist caught between Stalinism and anti-fascism. Frankfurt am Main, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-631-48043-1 . (Table of contents here [1] )

- Karlheinz Pech : A new witness in the death of Willi Münzenberg. In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement. 37th year, issue 1/1995, pp. 65–71.

- Reinhard Müller (sociologist, 1944) : Willy Münzenberg. In: Manfred Asendorf, Rolf von Bockel (eds.): Democratic ways. German résumés from five centuries. Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01244-1 , pp. 439-441.

- Tilman Schulz: Munzenberg, Willi. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-428-00199-0 , pp. 553 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Sean McMeekin : The Red Millionaire. A Political Biography of Willi Munzenberg, Moscow's Secret Propaganda Tsar in the West . Yale University Press, New Haven 2003, ISBN 0-300-09847-2 .

- Stephen Koch: Double Lives: Stalin, Willi Munzenberg and the Seduction of the Intellectuals. revised Edition. Enigma Books, 2004, ISBN 1-929631-20-0 .

- Munzenberg, Willi . In: Hermann Weber , Andreas Herbst : German Communists. Biographisches Handbuch 1918 to 1945. 2nd, revised and greatly expanded edition. Dietz, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-320-02130-6 .

- Reinhard Müller : That will destroy the strongest horse. Willi Munzenberg's settlement with the machine. In: Yearbook for Historical Research on Communism . Aufbau Verlag , 2010, pp. 243–265.

- Ralf Hoffrogge: Conference report of a scientific conference on u. a. The life of Munzenberg in 2012 : internationalism, transnational solidarity networks, anti-fascism and anti-Stalinism in the 1920s and 1930s - European Willi Munzenberg workshop.

- Kasper Braskén: Willi Münzenberg and the International Workers Aid (IAH) 1921–1933: a new story. In: Year Book for Research on the History of the Labor Movement . Issue III / 2012.

- Dieter Schiller: Willi Münzenberg and the intellectuals. The years in the Weimar Republic. In: Yearbook for research on the history of the labor movement . Issue III / 2013.

- John Green: Willi Munzenberg. Fighter against Fascism and Stalinism , Routledge, London 2020, ISBN 978-0-367-34472-6 .

- History of literature, media studies and media history

- Peter de Mendelssohn : Berlin newspaper city. People and Powers in the History of the German Press. Ullstein Verlag , Berlin 1959. * Heinz Willmann : History of the Arbeiter-Illustrierte Zeitung 1921–1938. Dietz, East Berlin 1974.

- Rolf Surmann: The Munzenberg Legend. On the journalism of the revolutionary German labor movement 1921–1933. Prometh Verlag, Cologne 1982, ISBN 3-922009-53-0 .

- Martin Mauthner: German Writers in French Exile, 1933–1940. Vallentine Mitchell Publishers, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-85303-540-4 .

Films about Willi Munzenberg

- Willi Munzenberg or The Art of Propaganda. Documentation, 62 minutes, Germany 1995, director: Alexander Bohr, production ZDF / ARTE; Broadcast on September 26, 1995 on ARTE

- Munzenberg - The last course. Documentary, 45 minutes, Germany 1992, director: Hans-Dieter Rutsch, on behalf of WDR

- Propaganda as a weapon. Documentation, 45 minutes, Germany 1982, directors: Thomas Ammann, Jörg Gremmler, Matthias Lehnhardt, Gerd Roscher, Ulrike Schaz, Walter Uka, production: WDR 1982, editing: Ludwig Metzger

- Escape - the Munzenberg case. Drama, 90 minutes, Germany 1971, TV production, director: Dieter Lemmel, actors: Kurt Jaggberg, Günter Mack, Willi Semmelrogge

Exhibition on Willi Münzenberg

- The Red Thread. Munzenberg as a bridge to the 21st century. Kunsthaus Erfurt, June 16 to July 17, 2015

Podcast

- Portrait of Willi Münzenberg as a podcast on Bayern 2 radioZeitreisen ( memento from July 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), length 24:39 minutes

Web links

- Literature by and about Willi Münzenberg in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Willi Münzenberg in the German Digital Library

- Newspaper article about Willi Münzenberg in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- International Willi Munzenberg Forum

- Willi Munzenberg in the database of members of the Reichstag

- Willi Munzenberg. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Short biography of the German Resistance Memorial Center

- Willi Münzenberg in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Steffen Raßloff : Willi Munzenberg: The red propaganda tsar. In: Erfurt-Web.de , February 18, 2012.

- Jochen Stöckmann: The voice of the workers. In: Deutschlandfunk . August 14, 2014.

- Ralf Hoffrogge: International Willi Munzenberg Congress 2015. Report from the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation .

Remarks

- ↑ The first edition of the AIZ after Hitler came to power was available in April 1933 from the magazine distributor Joseph Wildner, Reichenberg (CSR) Hafnergasse 7. It contained z. Eg a report by Egon Erwin Kisch “In the Casemates of Spandau”. The magazine Our Time was published from April 1, 1933 with no. 7/1933 (in the sixth year) first in Basel and then in Paris (e.g. no. 15/1933). Another magazine appeared in Prague from September 15, 1933, the counter attack (announcement in issue 12 Our Time ).

- ↑ The contact was via the address Amsterdam, Elandstraat 33. (Source: Our time 7/1933).

- ↑ Also in 1935, Christopher Isherwood published the novel Mr Norris Changes Trains , in which Münzenberg played a role as a minor character, "Ludwig Bayer".

- ^ David Pike : German writers in Soviet exile 1933–1945 . For example, Ruth Rewald appeared: Janko, the boy from Mexico and Kurt Kersten: Under freedom flags. Sebastian Brant, Strasbourg 1938.

- ↑ The exact date of the exclusion is questionable, Wilhelm Pieck's Münzenberg hand file allows both March 21 and May 14, 1938, because with these dates two differently worded “decision texts” exist. The decision of the Central Committee of the KPD on Willi Munzenberg's exclusion appeared in the Deutsche Volkszeitung No. 21 on May 22, 1938 , but does not correspond to the text of May 14, 1938 approved by the German Commission of the EKKI, but to the one with “Draft / 4 Expl “Subtitled, much more brutally worded text from March.

- ↑ “Those who do not forget, Babette Gross, Arthur Koestler, the writer Kurt Kersten, whisper that Munzenberg was eliminated by Stalinist killers, just like Leon Trotsky , two months later, on August 20, 1940 in Mexico. “(“ Ceux qui n'oublient pas, Babette Gross, Arthur Koestler, l'écrivan Kurt Kersten, soufflent que Münzenberg a été éliminé par des tueurs Staliniens, tout comme Léon Trotsky, assassiné deux mois plus tard, jour pour jour, le 20 août 1940, à Mexico. ») Alain Dugrand and Frédéric Laurent: Willi Münzenberg. Artiste en révolution (1889–1940). Librairie Arthème Fayard, Paris 2008, p. 548. In the book: A God Who Wasn't, Zurich 1950, p. 70, Arthur Koestler wrote: Munzenberg "was murdered in the summer of 1940 under the usual mysterious circumstances; as almost always in such Cases, the murderers are unknown, but the evidence all points in the same direction as the magnetic needle pointing to the pole ".

Individual evidence

- ^ Babette Gross : Willi Munzenberg. A political biography. Stuttgart 1967, p. 37.

- ^ K. Haferkorn: Munzenberg, Wilhelm. 1970, p. 340.

- ^ Babette Gross: Willi Munzenberg. A political biography. Stuttgart 1967, p. 228.

- ↑ For the KPD's decision on the course, see Heinrich August Winkler : Der Weg in die Katastrophe. Workers and the labor movement in the Weimar Republic 1930 to 1933 . Dietz, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-8012-0095-7 , pp. 385-391.

- ↑ Jonathan Miles: The Nine Lives of Otto Katz. The Remarkable Story of a Communist Super-Spy. Bantam Books, London a. a. 2010, ISBN 978-0-553-82018-8 , p. 81.

- ^ Babette Gross: Willi Munzenberg. A political biography. Stuttgart 1967, p. 160. After Munzenberg escaped in 1933, the car was loaded onto a Soviet ship in Antwerp and sent to the Moscow IAH agency. (ibid., p. 279).

- ^ Siegfried Grundmann: Einstein's file. Science and politics - Einstein's time in Berlin. 2nd Edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin a. a. 2004, p. 425.

- ↑ Michael Hepp (Ed.): The expatriation of German citizens 1933-45 according to the lists published in the Reichsanzeiger . tape 1 : Lists in chronological order. De Gruyter Saur, Munich 1985, ISBN 978-3-11-095062-5 , pp. 3 (reprinted 2010).

- ↑ Bruno Frei : The paper saber. Autobiography. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1972, p. 183.

- ^ Willi Munzenberg. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- ↑ Gustav Regulator : The ear of Malchus. A life story. Stroemfeld Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Basel 2007, p. 263.

- ↑ Hans Magnus Enzensberger: Hammerstein or the obstinacy. A German story. Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp 2008, ISBN 978-3-518-41960-1 , p. 169.

- ↑ Arthur Koestler: The Secret Script. Report of a life. 1932 to 1940. Vienna a. a. 1955, p. 214.

- ↑ Manès Sperber : The futile warning. All the past ... 2nd edition. dtv, Munich 1979, 1980, p. 190.

- ↑ Manès Sperber: Until they put broken pieces on my eyes. All the past ... Europaverlag, Vienna 1977, p. 133.

- ^ Alfred Kantorowicz : Night Books. Records in French exile. 1935 to 1939. edited by Ursula Büttner and Angelika Voss. Christians Verlag, Hamburg 1995, p. 151. 300 Francs corresponded to about 12 dollars.

- ^ Margarete Buber-Neumann: From Potsdam to Moscow. Stations on a wrong path. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1957 (2nd edition 1958), p. 451.

- ↑ Sean McMeekin: The red millionaire. A political biography of Willi Münzenberg, Moscow's secret propaganda tsar in the West. Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2003, p. 274.

- ↑ Sean McMeekin: The red millionaire. New Haven / London 2003, p. 282.

- ^ "Circular letter to the communist faction of the committee", Babette Gross: Willi Munzenberg. A political biography. Stuttgart 1967, p. 314.

- ^ Large: Willi Munzenberg . 1967, p. 13f .; Otto R. Romberg: Resistance and Exile, 1933–1945 . Frankfurt am Main 1986, p. 249.

- ^ Harald Wessel: Munzenberg's end. A German communist in the resistance against Hitler and Stalin. The years 1933 to 1940 . Berlin 1991, p. 233.

- ↑ Harald Wessel: "... apparently killed himself". Investigation protocol for finding the body of Willi Munzenberg on October 17, 1940. In: Contributions to the history of the workers' movement. 33rd year, issue 1/1991, pp. 73–79.

- ^ Karlheinz Pech: A new witness in the death of Willi Munzenberg. In: Contributions to the history of the labor movement. 37th year, issue 1/1995, pp. 65–71. Report from a member of CALPO

- ^ Manfred Asendorf, Rolf von Bockel Ed .: Democratic Ways. German résumés from five centuries. Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01244-1 , p. 441.

- ↑ From Potsdam to Moscow. Stations on a wrong path. Stuttgart 1957, p. 198.

- ↑ Helmut Trothow: The legend of the red press czar . In: Die Zeit , No. 23/1984.

- ↑ Bruno Frei: The paper saber. Autobiography. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1972, p. 192.

- ↑ Karlen Vesper: He's back. There is now a Munzenberg forum on the Internet. In: Neues Deutschland from 29./30. March 2014, p. 25.

- ^ Website of the Munzenberg Forum .

- ^ Willi Munzenberg Congress on the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation website

- ↑ Global spaces for radical transnational solidarity. Contributions to the First International Willi Munzenberg Congress 2015 in Berlin , ed. by Bernhard H. Bayerlein, Kasper Braskén and Uwe Sonnenberg, Internationales Willi Münzenberg Forum, Berlin 2018, as a PDF file, accessed on July 12, 2018.

- ↑ kunsthaus-erfurt.de

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Munzenberg, Willi |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Munzenberg, Wilhelm |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politician (KPD), MdR and publisher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 14, 1889 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Erfurt |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 1940 |

| Place of death | Saint-Marcellin , Isere department , France |