Christopher Isherwood

Christopher William Bradshaw-Isherwood (born August 26, 1904 in High Lane , Cheshire , England , † January 4, 1986 in Santa Monica , California ) was a British - American writer . He became known for his Berlin Stories , which became the basis of the film musical Cabaret . As a senior citizen, Isherwood was one of the first literary exponents of the lesbian and gay movement .

Life

England

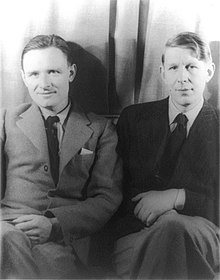

Christopher Isherwood was born to officer Frank Bradshaw-Isherwood and his wife Kathleen Machell-Smith. He had a brother seven years his junior. The father was killed in 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres the First World War . From 1914 he attended St. Edmund's School, where he made friends with WH Auden , and later the Repton School in Derbyshire , where he met Edward Upward in 1921 . He studied history in Cambridge , but failed the Tripos exam in 1925 . He lived temporarily with the violinist André Mangeot and worked as a secretary for his string quartet. In 1928 he began studying medicine at King's College London , but dropped out in 1929.

Berlin

In the same year he followed the writer WH Auden to Berlin . Both were fascinated by the inhospitableness, the pace and the gay scene of the city. "Berlin is every gay's dream", Auden wrote at the time, "There are 170 bars and restaurants monitored by the police". "For Christopher, Berlin was synonymous with 'boys'", Isherwood later summarized his fascination briefly. Almost every evening he and Auden visited prostitutes in the Hallescher Tor area in the Kreuzberg district . Her favorite place was Cozy Corner on Zossener Strasse, a dingy café where "half a dozen guys were hanging around and drinking beer".

Isherwood soon spoke fluent German. He financed his life as a language teacher and from quarterly donations from his wealthy uncle Henry Isherwood. At first he lived as a subtenant of Magnus Hirschfeld's eldest sister at the Institute for Sexology directly at the Großer Tiergarten , roughly where the congress hall now stands. In October 1930 he moved to the working-class district of Kreuzberg , first on Simeonstrasse, near the Prinzenstrasse underground station , and a month later on Admiralstrasse, right next to Kottbusser Tor . From December 1930 he lived for two and a half years in the middle of Berlin's gay and lesbian quarter, at Nollendorfstrasse 17, in the Schöneberg district , where a plaque commemorates him today. Two corners away was the dance cabaret Eldorado, famous for its transvestite shows, in which Marlene Dietrich also frequented. In March 1932 he met his first long-term partner in Berlin , the then 17-year-old Zugehmann Heinz Neddermeyer, with whom he lived for five years.

Europe and Asia

After the seizure of power of Hitler Isherwood left in May 1933 with his partner Germany. Until 1937 he lived successively on an island in the Gulf of Euboea , in London , on the Canary Islands , in Spanish Morocco , in Copenhagen , Brussels , Amsterdam and the small Portuguese town of Sintra . From October 1933 to February 1934 he worked in London for the Gaumont-British film studio on the film Little Friend , first as a screenwriter , then as a dialogue advisor to director Berthold Viertel . In 1938 he went on a report trip to China with WH Auden .

United States

In 1939 Isherwood emigrated with Auden from London to the United States . The US had long attracted him. At first he lived in New York City for about three months , but did not feel at home there. At the invitation of Gerald Heard , he traveled with the Greyhound Lines via New Orleans and Houston to California . Although he considered Los Angeles “perhaps the ugliest city in the world”, he decided to stay: “Los Angeles is a great place to feel at home because everyone comes from somewhere else.” Because he wasn't ready to speak German to shoot, he registered himself as a conscientious objector after the USA entered World War II . In 1941 and 1942 he lived in Haverford, Pennsylvania , where he taught English to German refugees at Haverford College on behalf of the Quaker organization Society of Friends . Two of his students there were Hermann and Gretel Ebeling .

The writer Henry F. Heard had introduced it to the Hindu monk Swami Prabhavananda , who was head of the Vedanta Society of Southern California, in 1939 . For him, Prabhavananda became a kind of father figure and creator of meaning. After returning to California in 1943, he helped him translate the Bhagavad Gita into English. In 1944 he lived briefly as a monk in the Vedanta Center Los Angeles, but left because he did not want to be sexually abstinent.

Isherwood became a US citizen in 1946. In the late 1940s he moved to Santa Monica , traveled with his partner Bill Caskey through South America and published a book on it. He worked as a screenwriter for the film studios in Hollywood and met writers and actors there. He was friends with the writers Tennessee Williams , Aldous Huxley and Kenneth Anger , the actors Charles Laughton , Jennifer Jones and Leslie Caron , the director John Boorman and the composer Igor Stravinsky and his wife Vera. In 1959, he bought a house over Santa Monica Canyon, a neighborhood popular with artists and writers. From 1959 to 1962 he was visiting professor for modern English literature at the Los Angeles State College of Applied Arts and Sciences .

From 1953 until his death, Isherwood was in a relationship with Don Bachardy, 30 years his junior . The writer encouraged the young man, who was initially studying languages, to develop his artistic talents and establish himself as a portrait painter. The couple edited dramatizations of the Isherwood novella Meeting By The River and the book October, as well as the script for the television film Frankenstein: The True Story . In old age, Isherwood became involved in the US gay rights movement . The Isherwood and Bachardy connection became a role model for the gay and lesbian community in the US. David Hockney painted a double portrait of the couple in 1968. Isherwood died of prostate cancer in his Santa Monica home in 1986 .

In 1949, Christopher Isherwood was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters .

Create

His first novels All the Conspirators (1928) and The Memorial (1932) are settlements with the then England. The novels Mr. Norris Rises (1935) and Lebwohl, Berlin (1939), also known as the Berlin Stories , established his reputation as a literary prodigy in England and shaped the image of Berlin in the Anglo-Saxon-speaking area in the early 1930s. They take up Isherwood's experiences in Berlin between 1929 and 1933. The most famous characters in the two novels were his roommates at the Thurau private pension on Nollendorfstrasse. In 1931 he met Jean Ross there, who became the model of the character of the capricious nightclub singer and aspiring actress Sally Bowles. Gerald Hamilton, who inspired Isherwood to become Mr. Norris, a journalist, communist and criminal, also lived in the Pension Thurau. In his novels, the landlady Meta Thurau became Lina Schröder, a typical Berliner for Isherwood, who, despite her initial rejection of National Socialism, finally came to terms with him.

In the United States, Isherwood got into a protracted crisis of creativity and meaning. Even in New York he had the impression that his talent as a writer had been used up. In Los Angeles his feeling of insecurity grew. Literary productivity dropped dramatically over two decades. He found his life in Santa Monica "empty, vain, trivial, tragic". He numbed himself with a lot of alcohol and sex. An autobiography from 1945 to 1951 was entitled Lost Years . Isherwood couldn't get away from Berlin. “There was always Berlin in the background”, he wrote in 1962 about his early years in the USA: “It called me every night and his voice was the rough, provocative voice of the gramophone record.” In 1949 Kondor und Kühe appeared: A South American travel diary with photos of his Co-partner Bill Caskey. The motifs of his Berlin Stories were first adapted for the Broadway play I Am a Camera (1951) and the film of the same name (1955), then for the musical Cabaret (1966) and the film Cabaret (1972).

The novel Praterveilchen plays in Vienna , published in 1945, and the book Down there on a Visit published in 1962 again thematizes Berlin at the end of the Weimar Republic . The 1964 published novel The Loner was his first thoroughly American work; it formed the basis for the 2009 film drama A Single Man . Isherwood wrote several works on the Indian philosophy of Vedanta in the 1950s and 1960s . In the 1970s, his works addressed his own homosexuality, sometimes in very drastic descriptions. The two Berlin novels from the 1930s were accompanied by the autobiography Christopher und die Seinen (1976), in which he wanted to correct things that had been hidden about himself.

Works (selection)

- 1928: All the Conspirators.

- German: ((All good intentions)). ISBN 978-3-455-40583-5 .

- 1932: The Memorial. Portrait of a Family.

- German: The monument. Portrait of a family. Translated by Georg Deggerich. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-455-40584-2 .

- 1935: Mr Norris Changes Trains. (US title: The Last of Mr. Norris.)

- German: Mr. Norris changes . ISBN 3-596-25453-1 .

- 1935: The dog beneath the skin; or, where is Francis? (together with WH Auden)

- 1937: Sally Bowles.

- 1936: The Ascent Of F6. (together with WH Auden)

- 1938: Lions and Shadows. ISBN 0-8112-0649-1

- German: lions and shadows. ISBN 978-3-937834-36-8 .

- 1938: On The Frontier. (together with WH Auden)

- 1939: Goodbye to Berlin. ISBN 978-0-8112-2024-8

- German: Farewell, Berlin . ISBN 3-548-24535-8 .

- 1939: Journey To A War. (together with WH Auden) ISBN 1-55778-328-4

- 1945: Prater Violet.

- German: Praterveilchen. ISBN 3-518-22287-2 .

- 1945: The Condor And The Cows. ISBN 978-0-09-956118-7

- German: Condor and cows: A South American travel diary. ISBN 978-3-95438-007-7 .

- 1951: What Vedanta Means To Me.

- 1954: The World In The Evening.

- German: The world in the evening. ISBN 978-3-455-40582-8 .

- 1962: Down There On A Visit.

- 1963: An Approach to Vedanta.

- 1964: A Single Man.

- German: The loner. ISBN 3-423-19005-1 .

- 1965: Ramakrishna And His Disciples.

- 1966: Exhumations.

- 1967: A Meeting By The River. ISBN 0-374-52076-3

- German: meeting on the river. ISBN 3-7610-8074-3 .

- 1969: Essentials Of Vedanta.

- 1971: Kathleen And Frank.

- 1973: Frankenstein: The True Story. (with Don Bachardy)

- 1976: Christopher And His Kind.

- German: Christopher and his family. ISBN 3-924163-78-2 .

- German: Welcome to Berlin. ISBN 978-3-86187-918-3 .

- 1980: My Guru And His Disciple.

- 1980: October / O . (with Don Bachardy)

- 1982: People one ought to know in New York. ill. by Silvain Mangeot. ISBN 0-385-17536-1

- German: familiar faces. ISBN 3-88803-010-2 .

- 1994: The Mortmere Stories. ISBN 1-870612-84-1 (with Edward Upward)

- 1998: Jacob's hands . (with Aldous Huxley) ISBN 0-312-19467-6

- 2007: Isherwood on writing. ISBN 0-8166-4693-7 . (Ed. James J. Berg)

literature

- Carolyn G. Heilbrun: Christopher Isherwood . Columbia University Press, New York 1970, ISBN 0-231-03257-9

- Sigurds Dzenitis: The Reception of German Literature in England by Wystan Hugh Auden, Stephen Spender and Christopher Isherwood . H. Lüdke, Hamburg 1972

- Jonathan Fryer: Isherwood. A biography . Doubleday & Company, Garden City 1977, ISBN 0-385-12608-5 .

- Brian Finney: Christopher Isherwood. A Critical Biography . Oxford University Press, 1979, ISBN 0-19-520134-5 .

- Stephen Spender: Letters to Christopher. Stephen Spender's letters to Christopher Isherwood, 1929–1939 . Black Sparrow Press, Santa Barbara 1980, ISBN 0-87685-470-6 .

- John Lehmann: Christopher Isherwood. A personal memoir . Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1987, ISBN 0-8050-1029-7 .

- Lisa M. Schwerdt: Isherwood's fiction. The self and technique . Macmillan, Basingstoke 1989, ISBN 0-333-45288-7

- Don Bachardy: Christopher Isherwood. Last drawings . Faber, London 1990, ISBN 0-571-14075-0

- Linda Mizejewski: Divine decadence. fascism, female spectacle, and the makings of Sally Bowles . Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1992, ISBN 0-691-07896-3

- Edward Upward: Christopher Isherwood. Notes in remembrance of a friendship . Enitharmon, London 1996, ISBN 1-900564-00-9

- Norman Page: Auden and Isherwood. The Berlin Years . Macmillan Press, Basingstoke 2000, ISBN 0-333-80399-X ; St. Martin's Press, New York 2000.

- James J. Berg, Chris Freeman (Eds.): The Isherwood Century. Essays on the Life and Work of Christopher Isherwood . The University of Wisconsin Press, Chicago 2000, ISBN 0-299-16704-6 .

- James J. Berg, Chris Freeman (Eds.): Conversations with Christopher Isherwood . University of Mississippi Press, Jackson 2001, ISBN 1-57806-407-4 .

- David Garrett Izzo: Christopher Isherwood. His era, his gang, and the legacy of the truly strong man . University of South Carolina Press, Columbia 2001, ISBN 1-57003-403-6

- Claude J. Summers: Christopher Isherwood . Frederick Ungar, New York 1981, ISBN 0-8044-6885-0

- Lee Prosser: Isherwood, Bowles, Vedanta, Wicca, and Me . iUniverse, 2001, ISBN 0-595-20284-5 .

- Catrin Kuhlmann: The connection between social criticism, Vedanta and sexual identity. Christopher Isherwood's narrative as a literary coming out . Braunschweig, Techn. Univ., Diss., 2001.

- Julius H. Schoeps : A portion of cowardice. In: Die Welt , May 10, 2003.

- Julius H. Schoeps: "Where love is mostly hugger mugger." Christopher Isherwood, Magnus Hirschfeld and Berlin on the eve of the disaster. In: Elke-Vera Kotowski , Julius H. Schoeps (Ed.): Magnus Hirschfeld. sifria, Berlin 2004, pp. 342–356.

- Peter Parker: Isherwood . Picador, London 2005, ISBN 978-0-330-32826-5

- David Garrett Izzo: Christopher Isherwood Encyclopedia . McFarland & Co., Jefferson, NC 2005, ISBN 0-7864-1519-3

- Jamie M. Carr: Queer times. Christopher Isherwood's modernity . Routledge, London 2006, ISBN 978-0-415-97841-5

- Richard E. Zeikowitz (Ed.): Letters between Forster and Isherwood on homosexuality and literature . Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-60675-3

- Victor Marsh: Mr Isherwood changes trains. Christopher Isherwood and the search for the home self . Clouds of Magellan, Melbourne 2010, ISBN 978-0-9807120-5-6

- Keith Garebian: The making of Cabaret . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-973249-4

- Jaime Harker: Middlebrow queer. Christopher Isherwood in America . University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2013, ISBN 978-0-8166-7913-3

Film adaptations

script

- 1934: Little Friend

- 1939: The Mad Dog of Europe

- 1941: Dangerous Love (Rage in Heaven)

- 1943: For ever and a day (Forever and a Day)

- 1949: The player (The Great Sinner)

- 1955: Diane - Courtesan of France (Diane)

- 1965: Death in Hollywood (The Loved One)

- 1966: Only one woman on board (The Sailor from Gibraltar)

- 1973: Frankenstein as he really was (Frankenstein: The True Story)

Literary template

- 1972: Cabaret

- 2009: A Single Man

- 2010: Christopher and Heinz - A Love in Berlin (TV movie)

Web links

- Literature by and about Christopher Isherwood in the catalog of the German National Library

- Christopher Isherwood in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Christopher Isherwood in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (English)

- Christopher Isherwood in the nndb (English)

- The Christopher Isherwood Foundation

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center: Christopher Isherwood: Biographical Sketch (English).

- ↑ Julia Reuter: The Question of Authenticity in Christopher Isherwood's Autobiographical Writings , Master Thesis, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, February 28, 2011, p. 5

- ^ Adam Mars-Jones : All about darling Me , The Observer, May 23, 2004. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ Julius H. Schoeps: “Where love is mostly hugger mugger”. Christopher Isherwood, Magnus Hirschfeld and Berlin on the eve of the disaster ( memento of October 20, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 115 kB). In: Elke-Vera Kotowski, Julius H. Schoeps (Ed.): Magnus Hirschfeld . sifria, Berlin 2004, pp. 342–356

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood: Welcome to Berlin. Christopher and his family. Bruno Gmünder Verlag, Berlin 2008, p. 2

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood 2008, pp. 33ff.

- ^ Richard Davenport-Hines: Auden . William Heinemann, London 1995, pp. 87ff.

- ^ Norman Page: Auden and Isherwood. The Berlin Years . Macmillan Press, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, London 2000, pp. 129ff.

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood 2008, p. 19

- ↑ Raimund Wolfert: Stumbling block for Recha Tobias , Federal Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation, March 27, 2013. Accessed on August 22, 2018.

- ^ A b c Rachel B. Doyle: Looking for Isherwood's Berlin. In: The New York Times , April 12, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood 2008, p. 51.

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood 2008, p. 55.

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood 2008, pp. 89ff.

- ^ Gay History Wiki: Heinz Neddermeyer

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood 2008, pp. 128f.

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood 2008, pp. 132ff.

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood 2008, pp. 142ff.

- ↑ WI Scobie: Christopher Isherwood, The Art of Fiction No. 49. In. theparisreview.org , 1974. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ a b c Ulf Lippitz: Christopher Isherwood: The long breath. In: Der Tagesspiegel , April 4, 2010. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- ↑ James J. Berg: Conversations with Christopher Isherwood , University Press of Mississippi (English)

- ↑ Bundesarchiv Koblenz: Holdings BArch N 1374/49: Personal memories of Grete Ebeling, p. 21-22

- ↑ a b Christopher Isherwood: Lost Years. A Memoir 1945–1951. HarperCollins, New York 2000 (English)

- ↑ Marko Martin: Evita cult and fearful erection deification In: Die Welt. March 14, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ Edmund White: A Love Tormented but Triumphant. In: The New York Times. December 9, 2010.

- ^ Peter Conrad: Christopher Isherwood remembered. In: The Guardian. 17th October 2010.

- ^ The Christopher Isherwood Foundation: Biography

- ^ Members: Christopher Isherwood. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed April 5, 2019 .

- ↑ Peter Conrad: Tom, Dick and Christopher , The Guardian, July 2, 2000.

- ↑ a b Christopher Isherwood 2008, p. 61ff.

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood 2008, pp. 59ff.

- ↑ Christopher Isherwood 2008, pp. 7ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Isherwood, Christopher |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Bradshaw-Isherwood, Christopher William (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British-American writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 26, 1904 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | High Lane , Cheshire , United Kingdom |

| DATE OF DEATH | 4th January 1986 |

| Place of death | Santa Monica , California , United States |