Canary Islands

|

Canarias ( Spanish ) Canaries |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Basic data | |||||

| Country : |

|

||||

| Capital : |

Santa Cruz de Tenerife and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria |

||||

| Area : | 7,492.49 km² | ||||

| Residents : | 2,153,389 (January 1, 2019) | ||||

| Population density : | 287.4 inhabitants / km² | ||||

| Expansion: | North – South: approx. 212 km West – East: approx. 340 km |

||||

| Time zone : |

UTC UTC + 1 (March to October) |

||||

| ISO 3166-2 : | ES-CN | ||||

| Website : | www.gobiernodecanarias.org | ||||

| Anthem : | Himno de Canarias | ||||

| Politics and administration | |||||

| Autonomy since: | August 16, 1982 | ||||

| President : | Ángel Víctor Torres Pérez ( PSOE ) | ||||

| Representation in the Cortes Generales : |

Congress : 14 seats Senate : 3 indirectly, 11 directly elected seats |

||||

| Structure : | 2 provinces | ||||

The Canary Islands ( Spanish Islas Canarias ) or Canaries are a geological group of islands belonging to Africa , politically to Spain (and thus to the EU ) and biogeographically to Macaronesia , consisting of eight inhabited and a number of uninhabited islands in the eastern central Atlantic , about 100 to 500 kilometers west of the coast of Morocco . The Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands ( Spanish Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias ) is one of the 17 autonomous communities in Spain .

The Canary Islands belong to the Schengen area and the customs area of the European Union, but not to the tax area for excise duties and VAT . While border controls on persons within the Schengen area no longer take place, customs controls with destination or origin in the Canary Islands are still possible.

geography

The Canary Islands are located in the Atlantic in a geographic region known as Macaronesia. These also include Cape Verde , the Azores , the Madeira Archipelago and the uninhabited islands of Selvagens . Between around 27 ° 38 'and 29 ° 30' north latitude and 13 ° 22 'and 18 ° 11' west longitude , the Canary Islands are located between 1028 and 1483 kilometers from motherland Spain (with Cape Trafalgar as the outermost point) Latitude with the Sahara , Kuwait and Florida . In contrast to mainland Spain, Western European Time applies .

The Canaries consist of seven islands with their own island administration ( Cabildo Insular ) , another inhabited island ( La Graciosa ) and five uninhabited islands. In addition, there are many small uninhabited rock islands directly on the coast such as the Roques de Salmor (0.035 km²) in front of El Hierro, the Roques de Anaga (0.01 km²) and the Roque de Garachico (0.05 km²) in front of Tenerife . The highest mountain in the Canary Islands and also in Spain is the 3715 meter high Pico del Teide on Tenerife.

| Islands with their own administration | Islands without their own administration | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tenerife | 2034 km² | - | |

| Fuerteventura | 1660 km² | Lobos | 4.58 km² |

| Gran Canaria | 1560 km² | - | |

| Lanzarote | 846 km² | La Graciosa | 29 km² |

| Alegranza | 10.30 km² | ||

| Montaña Clara | 1.48 km² | ||

| Roque del Este | 0.06 km² | ||

| Roque del Oeste | 0.015 km² | ||

| La Palma | 708 km² | - | |

| La Gomera | 370 km² | - | |

| El Hierro | 269 km² | - | |

geology

The canary threshold

The archipelago of the Canaries belongs geologically to Africa. It is located on the African Plate , on the eastern edge of the Canary Basin, which drops to a depth of 6501 meters. This lake basin in the Atlantic consists of the smaller north basin and the larger south basin, which are separated by the Canaries threshold , at the eastern end of which the Canaries rise. The borders of the entire basin are formed by the Azorean Sill in the north, the Cape Verde Sill in the south and the North Atlantic Ridge in the west .

Volcanism and erosion

The Canary Islands are an archipelago that owes its formation to intraplate volcanism and a hotspot below it . Both seismic tomography and geochemical analyzes indicate an anomaly deep in the earth's mantle as the source of the magmas. The unsteady development of the islands over time can best be explained with what is known as edge-driven convection , which swirls up a rising plume .

Geologically, the islands have been active until recently, and some of them are still volcanically active. The eastern islands of Fuerteventura and Lanzarote are the oldest with 22 million years and 15.5 million years, respectively. Gran Canaria arose around 14.5 million years ago, La Gomera around 11 million years ago and Tenerife around 12 million years ago. La Palma and El Hierro are the youngest islands of the archipelago with 2 and 1.2 million years respectively.

The hotspot migration is seen as the most conclusive explanation for the formation of the Canary Island chain: Above the fixed hotspot, the African plate migrates northeastward at a drift speed of 1.2 cm / year. The value is derived from the period between the Canary Islands and the youngest island of El Hierro and the distance between the islands. The drift speed determined in the GPS at the La Palma location in the period from 2008 to 2012 is 1.7 cm / year and 1.6 cm / year (measured via the shift on the latitude and longitude).

Each island has an individual history, except for Lanzarote and Fuerteventura, which have had a similar geological history. The two islands and the neighboring island of Lobos were connected to a single island for millennia during the low water level in the cold periods . Even today, it is only separated by a strait about 40 meters deep and about 10 kilometers wide.

In general, geologists assume a three-phase evolutionary history, which is proven with the help of argon isotope dating of volcanic rocks: It began at least 142 million years ago with submarine eruptions , with cushion lavas , hyaloclastites and intrusions initially forming submarine mountains. After several million years these rose above the sea surface and shield volcanoes built up in continuous eruption series (cf. Hawaii or Surtsey ). After that, there was an eruptive pause lasting several million years on the oldest volcanic islands of Fuerteventura, Lanzarote, Gran Canaria and La Gomera, which can be demonstrated by strong erosion above sea level. Later renewed volcanism in the Pliocene and Quaternary periods formed the islands. Here, too, periods of rest with layers of erosion can be detected.

As a result, there were repeated flank collapses and debris avalanches on all islands, the rubbish fans of which are still detectable far into the sea. Along with large explosive eruptions, the large calderas also formed on Gran Canaria, Tenerife and La Palma.

The volcanic activity continues with major eruptions in the 18th century on Lanzarote and the last eruption on land on La Palma in 2021 to the present day: From October 10th, 2011, about 270 meters below sea level and a few kilometers south of the coast in front of the island of El Hierro, a new volcano whose ejection products also reached the surface of the sea; the submarine eruptions ended in early March 2012.

climate

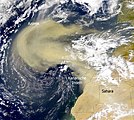

The subtropical climate of the Canary Islands is pleasant all year round due to its proximity to the northern tropic between the 27th and 29th parallel, which has earned the archipelago the nickname Islands of Eternal Spring . The consistently cool Canary Current , part of the Gulf Stream , balances out the temperatures, and the northeast trade wind mostly keeps the hot air masses away from the nearby Sahara and occasionally brings precipitation, especially on the northern coasts of the islands. An exception is the weather situation called Calima , which brings dry, hot air with fine Sahara sand to the islands with a southeast wind. Basically, a distinction can be made between a dry season in summer and a rainy season in winter; the southern regions of the islands are drier than the northern ones. In the coastal regions, the average temperatures are barely higher than 25 ° C in summer and around 18 ° C in winter.

Weather situation at Calima

In addition, there is a significant dependence of the climate on the topography of the islands. The north-east trade wind has a significant influence on the high western islands, the north-east of which is significantly more humid and cooler than the south due to heavy cloud formation on the mountains. Since the height differences on these islands are very large compared to the area, there are clearly differentiated vertical climatic zones. These range from the dry and hot coastal regions to the cool and humid and therefore often forested zones to cool and dry zones with a partially high mountain climate. The trade winds have little influence on the flat eastern islands of Lanzarote and Fuerteventura , which have an arid (dry) climate throughout . In addition, microclimates with a large variety of plants exist on all islands in areas of deep gorges and high rock walls.

flora

The flora of the Canary Islands is characterized by both a high level of biodiversity and a high proportion of site-specific plant species. According to current estimates, there are around 2000 plant species in the Canary Islands, 514 of which are Canarian endemics , of which 57 percent occur exclusively on one of the islands. The flora in the archipelago is heavily dependent on the altitude, the amount of rain and the nature of the soil. It is therefore extremely different from island to island. Studies of plants on the Canary Islands by Manuel Steinbauer show clear differences in the occurrence of endemic plants. While worldwide unique species make up around 25 percent of the vegetation in the lowlands, it is more than 50 percent at the 2400 meter high Roque de los Muchachos of La Palma . On Tenerife , around 30 percent of the plant species are endemic in the lowlands, at 3,000 meters on the Teide , this proportion increases to up to 65 percent.

The endemic Canary Pine is a specialty . Since its existence on the Canary Islands, it has been subject to high evolutionary pressure as a result of the recurring volcanic eruptions and the devastating fires associated with them (according to Anke Jentsch, Research Area Disturbed Ecosystems, in). The pine withstands the fires by protecting its tribal buds from the flames under its very thick bark. A short time after the end of the fire, the buds sprout again from the charred trunk.

In vegetation studies , the Canaries and Madeira are part of the Macaronesian region. Generally speaking, today there are close family ties to the North African and Mediterranean flora.

The largest Canarian dragon tree grows in Tenerife.

A Canary Island pine shortly after a forest fire - new shoots indicate how it has adapted to the volcanic fire hazard.

fauna

The fauna in the Canaries is mainly determined by reptiles and birds.

The Gallotia lizard genus is endemic to the archipelago . It comprises a total of eight species ( Eastern Canary Lizard ( G. atlantica ), La Palma Giant Lizard ( G. auaritae ), La Gomera Giant Lizard ( G. bravoana ), Small Canary Lizard ( G. caesaris ), Canary Lizard ( G. galloti ), Tenerife giant lizard ( G. intermedia ), El Hierro giant lizard ( G. simonyi ), Gran Canaria giant lizard ( G.stehlini )). These include some very large forms up to 80 centimeters in total length, which is why the animals are also known as giant lizards.

Other genera of reptiles that occur there are:

- the chalcides ( Chalcides ) with four species: Southern Kanarenskink ( C. coeruleopunctatus ), West Canary Skink ( C. viridanus ), Gran Canaria skink ( C. sexlineatus ) and Chalcides Simonyi ( C. simonyi )

- the gecko genus Tarentola with five species: Canarian wall gecko ( T. angustimentalis ), canary gecko ( T. delalandii ), striped canary gecko ( Tarentola boettgeri ) Gomera gecko ( T. gomerensis ) and wall gecko ( T. mauritanica )

- the European half finger ( Hemidactylus turcicus ).

Snakes did not originally live on the islands. At the end of the 20th century, however, Californian chain snakes (Lampropeltis getula californiae) were introduced by humans to Gran Canaria. Although they are non-toxic, they multiply particularly in the northeast of the island and threaten endemic species. From 2007, measures were taken to control the population and to prevent the further spread of the snakes.

The largest reptiles in the Canary Islands are the sea turtles (Cheloniidae) that live near the coast . In general, the marine fauna is rich in species with almost 550 species of fish. Worth mentioning include some ray species , many shark species, such as angel sharks , several hammerhead , mako sharks , great white sharks , as well as swordfish and barracuda as well as large tuna , sea bream , parrot fish , serration and brick perch , wings Butte and Pollack . In addition, 28 whale and dolphin species have so far been detected in the archipelago, including the largest living predator - the sperm whale .

In the constantly damp cloud forests also have amphibious settled ( Mediterranean Tree Frog ( Hyla meridionalis ), Perez's Frog ( Pelophylax perezi )).

Small Canary Lizard ( Gallotia caesaris gomerae )

Serinus canaria - the Canary Girlitz , ancestor of the yellow-bred canaries

Canary Whites in Tenerife

The Canary Shrew was only discovered on Fuerteventura in 1985.

The bird world of the Canaries is made up of endemics from the Canaries and Madeira, typical species from the Mediterranean and North Africa and Palearctic cosmopolitans . Of the latter, endemic subspecies have emerged here in numerous species .

The endemic species that are also native to Madeira include the single-color swift , the Canary Pipit and the Canary Girlitz , the wild stem form of the canary . The Canary Chiffchaff ( Phylloscopus canariensis ) breeds on all Canary Islands, the Canary Islands only on the western ones. The laurel pigeon and Bolles laurel pigeon only occur on La Palma, Tenerife and Gomera, the latter species also on El Hierro. The Teydefink is only to be found on Tenerife and Gran Canaria, the Canarian slacker ( Saxicola dacotiae ) breeds with around 1000 pairs only on Fuerteventura.

Examples of typical species from the Mediterranean are the Eleonora's Falcon , which Mittelmeermöwe (ssp. Atlantis ), Sardinian Warbler (ssp. Leucogastra ) and Spectacled Warbler (ssp. Orbital ), the Sparrow and the Southern Gray Shrike (ssp. Koeningi ). Examples of representatives of the North African avifauna are the rock grouse , the desert falcon , the collar bustard , the sand grouse , the racing bird and the desert bullfinch . Among the subspecies of birds that are endemic here in Europe, those of the chaffinch ( F. c. Canariensis and palmae ) should be mentioned, which differ significantly from the nominate forms . There are other endemic subspecies of kestrel , barnacles and long-eared owls , great spotted woodpeckers , gray wagtails , blackbirds , bloodlines , blackcaps and robins . The tits are represented in the Canary Islands by the Canary Islands tit , which was originally considered a subspecies of the blue tit .

The insect world is represented with several thousand species. These include numerous butterflies with endemic species such as the Canary Whites ( Pieris cheiranthi ), the Canary Admiral ( Vanessa vulcania ) and the Canary forest board game ( Pararge xiphioides ). Dragonflies are common . Also locusts are common. The voracious swarms of locusts coming from Africa could become a nuisance until the middle of the twentieth century. Today they are already being treated with insecticides out at sea in such a way that this threat is practically no longer there.

For economic reasons, the cochineal scale insect and its host plant, the opuntia , were imported from Central America . A carmine-red dye was obtained from the lice, which is now manufactured synthetically.

The few mammals living in the wild , with the exception of most bats (such as the Madeira bat , the alpine bat or the white-edged bat ), were only released after the conquest or immigrated as fellow travelers. It was not until the 1980s that an endemic shrew species was discovered on Fuerteventura and subsequently also on Lanzarote and recorded as a separate species. In particular, the wild goat , the European mouflon , the barbary sheep and the wild rabbit cause severe damage to the endemic flora of the Canary Islands. Feral domestic cats are held responsible for the fact that the large lizards of the western islands are now threatened with extinction.

| Invasive mammals | Lanzarote | Fuerteventura | Gran Canaria | Tenerife | La Gomera | La Palma | El Hierro |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algerian hedgehog ( Atelerix algirus ) | x | x | x | x | |||

| House shrew ( Crocidura russula ) | x | ||||||

| Etruscan shrew ( Suncus etruscus ) | x | ||||||

| Egyptian bat ( Rousettus aegyptiacus ) | x | ||||||

| Domestic cat ( Felis catus ) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Wild goat ( Capra hircus ) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| European mouflon ( Ovis gmelini ) | x | ||||||

| Barbary sheep ( Ammotragus lervia ) | x | ||||||

| Atlas squirrel ( Atlantoxerus getulus ) | x | ||||||

| Black rat ( Rattus rattus ) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Brown Rat ( Rattus norvegicus ) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Western house mouse ( Mus domesticus ) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Wild rabbit ( Oryctolagus cuniculus ) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

The following are kept as pets: goats , sheep , horses , donkeys , mules , pigs , cows , dogs , cats , dromedaries (kept as pack animals on Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Gran Canaria), chickens and turkeys .

Nature reserves

There are a total of 146 nature reserves on the archipelago , which extend to 301,335 hectares. These include eleven nature parks with a total area of 111,022 hectares as well as 131 different nature reserves, natural monuments, landscape protection areas, places of scientific interest and rural parks. Also belonging to it, the Canaries in their autonomous community have the most national parks in Spain , four of a total of 13, with a total area of 32,681 hectares:

- Caldera de Taburiente National Park (La Palma)

- Garajonay National Park (La Gomera)

- Teide National Park (Tenerife)

- Timanfaya National Park (Lanzarote)

Since December 2006, the Canary Islands have belonged to the group of particularly vulnerable marine areas of the International Maritime Organization IMO . This means that a radius of twelve nautical miles (around 22.2 kilometers) is completely blocked for the transit of ships with dangerous cargo.

population

Until the 15th century, the archipelago was inhabited by the old Canaries , individual island populations who had no contact with one another. Although they differ in language and culture, the name of the largest group Guanches , the indigenous people of the island of Tenerife, is often used in popular scientific literature for all islanders . The Spanish conquest almost destroyed their culture, but many of these natives mixed with the new settlers. About a third of the current population of the islands descends in the female line from the old Canaries. The new settlers who came to the islands in the 16th century immigrated from the south of the Spanish peninsula and from what is now Portugal.

The inhabitants of the individual islands are called Tinerfeños (Tenerife), Grancanarios (Gran Canaria), Palmeros (La Palma), Majoreros (Fuerteventura), Gomeros (La Gomera), Lanzaroteños (Lanzarote) and Herreños (El Hierro).

Population development

The population of the Canary Islands has increased steadily over the past century. The trend continues to intensify, so that, according to the Spanish statistical office , the two million inhabitant mark was exceeded in May 2006. The development of the population according to the population register (Padrón Municipal de habitantes) from 2003 onwards is as follows:

| resident | 1976 | 2003 | 2005 | 2008 | 2015 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain as a whole | 35,701,000 | 42,717,064 | 44.108.530 | 45.828.172 | 46,624,382 | 47,450,795 |

| Canaries as a whole | 1,342,810 | 1,894,868 | 1,968,280 | 2,075,968 | 2.100.306 | 2,175,952 |

| Tenerife | 567,404 | 799.889 | 838,877 | 886.033 | 888.184 | 928604 |

| Gran Canaria | 591,445 | 789.908 | 802.247 | 829.597 | 847.830 | 855.521 |

| Lanzarote | 47,521 | 114.715 | 123.039 | 139.506 | 143.209 | 155.812 |

| Fuerteventura | 24,663 | 74,983 | 86,642 | 100,929 | 107,367 | 119.732 |

| La Palma | 80.219 | 85,631 | 85.252 | 86,528 | 82,346 | 83,458 |

| La Gomera | 24,270 | 19,580 | 21,746 | 22,622 | 20,783 | 21,678 |

| El Hierro | 7,278 | 10.162 | 10,477 | 10,753 | 10,587 | 11,147 |

The strong population growth in the first decade of the millennium resulted mainly from immigration , led by citizens from the European Union (excluding Spain: 129,039) and the countries of Latin America (77,502).

A total of 276,680 officially registered citizens without Spanish citizenship live in the Canary Islands in 2019 (as of January 1), which corresponds to a share of 12.9%, the majority of which come from Italy (49,170), followed by Germans (25,619) and British (25,521). In addition, there are 333,621 citizens from other autonomous communities in Spain (15.5% of the population; as of 2019).

The largest communities

The following list contains the 25 largest municipalities in the Canary Islands (as of January 1, 2019). The largest municipality on an island is in bold. For comparison, the two largest municipalities of La Gomera and El Hierro were added to the list.

| rank | City / municipality | Island | resident |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | Gran Canaria | 379.925 |

| 2 | Santa Cruz de Tenerife | Tenerife | 207.312 |

| 3 | San Cristobal de La Laguna | Tenerife | 157.503 |

| 4th | Telde | Gran Canaria | 102,647 |

| 5 | Arona | Tenerife | 81,216 |

| 6th | Santa Lucía de Tirajana | Gran Canaria | 73,328 |

| 7th | Arrecife | Lanzarote | 62,988 |

| 8th | San Bartolomé de Tirajana | Gran Canaria | 53,443 |

| 9 | Granadilla de Abona | Tenerife | 50,146 |

| 10 | Adeje | Tenerife | 47,869 |

| 11 | La Orotava | Tenerife | 42,029 |

| 12th | Puerto del Rosario | Fuerteventura | 40,753 |

| 13 | Arucas | Gran Canaria | 38,138 |

| 14th | Los Realejos | Tenerife | 36,402 |

| 15th | Agüimes | Gran Canaria | 31,619 |

| 16 | Ingenio | Gran Canaria | 31,321 |

| 17th | Puerto de la Cruz | Tenerife | 30,468 |

| 18th | Candelaria | Tenerife | 27,985 |

| 19th | Gáldar | Gran Canaria | 24,242 |

| 20th | La Oliva | Fuerteventura | 26,580 |

| 21 | Tacoronte | Tenerife | 24.134 |

| 22nd | Icod de los Vinos | Tenerife | 23,254 |

| 23 | Teguise | Lanzarote | 22,342 |

| 24 | Los Llanos de Aridane | La Palma | 20,467 |

| 25th | Mogan | Gran Canaria | 20,072 |

| 26 | San Sebastian de La Gomera | La Gomera | 9.093 |

| 27 | Valverde | El Hierro | 5,005 |

religion

Most of the Canarian population is baptized Roman Catholic. According to a survey conducted on the occasion of the regional and local elections in 2019, 77% of the population profess the Roman Catholic faith, with a majority of Catholics reporting that they rarely or never attend church services (apart from social events such as weddings). The number of places of worship was determined in a 2012 study. Evangelical Churches 155, Jehovah's Witnesses 45, Muslims 29, Buddhists 14, Adventists 10, Mormons 9, Bahá'ís 8, Anglicans 5, Jews 5.

- Roman Catholic Church

The Roman Catholic Church in the Canary Islands has existed since the division of a previously common diocese in 1819 from two dioceses subordinate to the Archdiocese of Seville as suffragan dioceses :

The Diocese of the Canary Islands ( Diócesis de Canarias ) extends over the province of Las Palmas and is therefore responsible for the eastern islands of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and Gran Canaria. Episcopal Church is the Santa Ana Cathedral . The seat of the bishop is the Episcopal Palace ( Palacio Episcopal ) on Plaza de Santa Ana opposite the cathedral.

The diocese of San Cristóbal de La Laguna ( Diócesis Nivariense or Diócesis de Tenerife ) was established on February 1, 1819 by Pope Pius VII and is congruent with the area of the province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife . It is based in San Cristóbal de La Laguna on Tenerife and is responsible for the western islands of Tenerife, La Palma, La Gomera and El Hierro. The Cathedral of Santa María de los Remedios was a parish church before the archipelago was divided into two dioceses. The residence of the bishop and seat of the ordinariate is the Palacio Salazar .

The Virgin of Candelaria is the patron saint of the Canary Islands. In her honor the Basilica of Candelaria was built as a pilgrimage church in the municipality of Candelaria .

The two missionaries canonized by the Catholic Church in Brazil and Guatemala José de Anchieta (1534–1597) and Peter von Betancurt (1626–1667) were born in Tenerife and are venerated in their places of birth.

language

The official language of the Canary Islands today is Spanish . The type of Spanish language spoken on the Canary Islands, together with Spanish spoken in Andalusia and Central and South America, form a language group known as Atlantic Spanish (español atlántico) or Southern Spanish (español meridional). Typical peculiarities are the frequent lack of the letter s in pronunciation, especially at the end of the word, and the replacement of the 2nd person plural by the 3rd person plural. There are also some words that are not in use on the mainland . (Example: guagua instead of autobús ).

Before the Spanish conquest, a different variety of the Guanche language was spoken on each Canary Island . Due to the systematic destruction of the ancient Canarian culture by the conquerors in the 15th and 16th centuries, only a few pieces of language have survived. These are primarily place names and names of plants that are endemic to the islands . Signs carved into stone have also been found that bear great resemblance to Libyan Berber . However, these are not related texts. On the island of La Gomera, a form of communication of the indigenous people has been preserved in which the acoustic characteristics of a spoken language are represented by whistles. The basic language of Silbo Gomero is no longer Guanche, but Spanish.

story

Antiquity

The Strait of Gibraltar formed the frontier of the inhabited world in Greco-Roman antiquity . Behind it, in the extreme west, the area where the sun went down, according to Greek mythology, was the world of darkness. According to the myth, Heracles had to go beyond the pillars of Heracles in the course of his work . There he procures the immortality-bringing apples of the Hesperides for the goddess Athena with the help of the titan Atlas , from whom Heracles takes away the vault of heaven. Likewise, the home was in the Atlantic Gorgon Medusa locates, the Perseus in Myth tees off his head, which he arms himself with a magic hat against her petrifying gaze. Furthermore, the Greek poets suspected the Elysian realms in the Atlantic , to which those heroes were raptured who were loved by the gods or to whom they gave immortality. These islands were the Happy Islands . A large part of the terms of Greek mythology were later related to the Canary Islands, but also to Madeira or the Cape Verde Islands , which are also located in the west outside the pillars of Heracles.

The first historically credible reports of journeys through the Strait of Gibraltar into the Atlantic date from the 5th century BC. From the Carthaginian sailors Hanno and Himilkon (both reports are lost today), from the description of the coast ( Periplus ) of the Pseudo-Skylax and from the Greek Pytheas , mentioned by Herodotus as well as Hannos Reise. Herodotus also reports in his histories that Phoenicians were already around 600 BC. On behalf of the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II. Sailed from east to west around Africa. Since Herodotus writes that the Phoenicians reported afterwards that they temporarily saw the sun on the other side of the sky, the seafarers must have actually at least crossed the equator.

Roman sources mentioned the Canary Islands for the first time expressly in the imperial period, namely in Pomponius Mela and Pliny Major ; they identified them as the "Islands of the Blessed" (Fortunatae insulae) . Pliny Major refers to descriptions of the Mauritanian king Juba II , who after the year 25 BC. The Fortunatae insulae was researched. Pliny Major clearly distinguishes the relatively well known Fortunatae insula of the Gorgonen Islands (Gorgaden, d. H. Kapverden , as compared to the Hesperu Ceras designated Cap Vert in Senegal) and of the Hesperiden . North of the Canaries, according to Pliny Major, are the islands of Atlantis ( Madeira ) and the Purple Islands.

First settlement

There are many speculations and assumptions about the origins of the native inhabitants of the Canary Islands, the old Canarians , but also about the way in which they came to the islands. Archaeological finds in Lanzarote that date back to the 10th century BC. BC, lead to the fact that today the hypothesis is put forward that the first contacts of the Phoenicians , presumably with the establishment of a base on this island, around the same time as the establishment of Lixus and Gades (around the 10th century BC) . Chr.) Took place. In the beginning, these were not settlements that could support themselves, but were dependent on regular contact with the Mediterranean region.

Due to archaeological finds, permanent settlement on most of the islands can be identified from the 3rd century BC at the latest. Prove. It is very likely that the settlers came from the regions of North Africa and southern Spain, which were then under Roman sovereignty. The settlement was not a one-off event. In a continuous process, different groups of settlers were brought to the islands with the necessary equipment. Archaeological finds show that at least between the 1st century BC BC and the 3rd century AD, there were close economic ties between the Canary Islands and parts of the Roman cultural area. From the Roman Empire crisis of the 3rd century , these relationships became less and less until they were completely discontinued by the 4th century at the latest. Since the inhabitants of the islands had no skills in shipbuilding and no knowledge of navigation, relations between the islands also broke off at this time.

Time of isolated development

In the period from the 4th century until the rediscovery of the Canary Islands by the Europeans in the 14th century, different cultures developed independently of one another on the individual islands. Although these were based on the same principles, they had so many special features that one cannot speak of a “Guanche culture of the Canary Islands”. There was the culture of the Majos on Lanzarote, that of the Majoreros on Fuerteventura, that of the Bimbaches on El Hierro, that of the Gomeros on La Gomera, that of the Canarios on Gran Canaria, that of the Benahoaritas on La Palma and that of the Guanches on Tenerife. The naming of the indigenous people of all islands with the name of the indigenous people of the island of Tenerife, as Guanches, which was common for a long time, ignores the differentiated cultural developments on the different islands. These resulted from the diversity of the topography, the fertility of the soil, the climate, the area of the islands and the size of the total population.

- Appearance

The appearance of the native inhabitants of the islands has been described differently by visitors since the beginning of the 14th century. In some reports, the light skin is mentioned in particular, which seemed so astonishing to the Europeans because they expected dark-skinned Africans so far south off the African coast. From anthropological studies of human remains that have been found on the islands, it follows that the Natives had dark hair and blond were only a few cases, especially as children. Blue eyes were common, but not the norm. With a height of about 1.70 m, the old Canary Islands were taller than the average Castilians of the 15th century. The written records give contradicting information about the clothing of the native inhabitants of the islands. While older information mostly mentions complete nudity, clothing made of fur and tanned leather is reported later.

- language

The languages of the indigenous people, collectively known as the Guanche , were so different that the Europeans who subjugated the islands in the 15th century found that their interpreters, who made contact with the indigenous people on one island, were the inhabitants of the other islands not understood. After the conquest and the forced assimilation of the indigenous population in the 15th century, the languages had disappeared by the end of the 16th century at the latest. By examining old place names, names of objects and personal names, a relationship between the languages and the Berber languages could be established.

- Social order

Each island had its own system of social and political organization, which was not repeated in all of its elements in the neighboring community. The social system of the heavily populated islands of Tenerife and Gran Canaria was significantly more marked by hierarchical differences than that of the sparsely populated islands such as El Hierro. The importance of women in these social systems is not proven by contemporary reports. At least on some islands, social status and property were passed on in a matrilineal manner. In Gran Canaria, Tenerife and Fuerteventura there are indications that women also exercised functions in the field of religion.

- nourishment

Goats, sheep and pigs were the basis of life on all islands. In addition, the gathering and, on some islands, the cultivation of grain, especially a special type of barley, was an important source of food. The grains were roasted, ground with hand mills and eaten as a gofio . For the cultivation of the grain there were irrigation systems on some islands . The warehousing and storage of grain reserves and seeds were regulated differently, depending on the importance of agriculture. Fishing took place only in the near shore area. In addition to the time in Lanzarote and Fuerteventura and the intervening island lying Lobos occurring monk seals were hunting season only lizards and birds. In addition, the fruits of the Canary Island date palm , which, like figs , grew wild on the islands, were part of the diet.

- religion

The first statements about the faith of the indigenous people of the Canary Islands can be found in the papal bull Ad hoc semper by Urban V (1369). This document stated that the inhabitants of these islands were worshipers of the sun and moon. Different names for the supreme deity have been passed down from the various groups of indigenous people on the islands. Research assumes that these were not just different names for one and the same deity, but that the indigenous people associated the names with very different ideas.

- funeral

Most of the old Canarian burials probably took place in caves. Earth graves and tumuli have also been found on various islands. There is archaeological evidence of cremations on the islands of El Hierro, Tenerife, La Palma, Fuerteventura and Lanzarote. Conservation of corpses by drying or additional mummification are known from some islands. The deceased were apparently dried or mummified according to their social status and sewn into a large number of goat skins. The importance that a person had during his lifetime is also shown in the richness of the grave goods. In archeology, grave goods are seen as obvious evidence of belief in the afterlife.

- Dwellings

The Canary Islands have a large number of bladder caves and lava tubes due to their volcanic origin . Most of the ancient Canaries lived in natural caves. A large number of artificial caves have been found in Gran Canaria. On the islands, where there are less suitable caves due to the geological conditions, or in areas that offered favorable living conditions without the presence of caves, the indigenous people also built houses out of stone. The type, size and layout of the buildings are different on each island. The only thing they have in common is that the walls are made of dry masonry .

- Everyday objects

Since there are no usable metal deposits in the Canary Islands, the indigenous people did not own any objects made of metal. The cutting tools were made of flint and, on some islands, of obsidian . Spears, skewers, and shepherds' sticks were made of wood. The tips were hardened in the fire. Ceramic vessels made without a potter's wheel are known from all islands. They were used for the transport of liquids, the storage of supplies, but also for roasting the grain for the production of gofio. In terms of shapes and decorations, there are hardly any similarities between the products of the indigenous people of the various islands. From animal bones found were in large quantities Ahlen made. They were used to pierce holes to join the leather for clothing or to open clams and other molluscs and to get edible parts out of the shells. Fish hooks made from bones have also been found.

- Rock paintings and rock inscriptions

Wall paintings , d. H. Colorants applied to the wall have so far only been found in Gran Canaria. Some petroglyphs were already known in the 18th century. But they were judged by the historians of the time to be “pure doodles, games of chance or the fantasy of the ancient barbarians”. At the beginning of the 20th century, further sites of petroglyphs were found on all islands . The research was largely limited to frequently incorrect reproductions, which were then compared with petroglyphs in North Africa, Europe and America. From 2008, projects were carried out to inventory the several hundred known rock inscriptions of the Canary Islands in order to collect and update all information about the sites. Some of the petroglyphs show large-scale geometric patterns or figurative representations. The indigenous people left rock inscriptions on all the islands . The characters belong to the group of Libyan-Berber scripts and are very similar to the characters found on old inscriptions in Northern Tunisia and Northeastern Germany.

Rediscovery of the Canary Islands in the 14th century

In the 14th century, seafarers from the Italian trade centers developed initiatives to make trade with India independent of the Arab countries in the Middle East through the sea route around Africa . The advances in shipping made it possible not only to reach the Canary Islands, but also to find a way back to Europe. The Genoese Lancelotto Malocello is believed to have established a trading post on the island of Lanzarote. An entry in a nautical chart by the Mallorcan cartographer Angelino Dulcert from 1339 describes this island as the island of the Genoese Lancelotto Malocello. It has been called Lanzarote ever since. As a result, there were various trips with the aim of exploring and conquering the islands on behalf of various rulers. In addition, there were also undertakings with the aim of catching the inhabitants of the islands and selling them as slaves in the markets of Spain and the Mediterranean.

The navigator of the research trip to the Canary Islands equipped by the Portuguese King Alfonso IV in 1341 , the Genoese Niccoloso da Recco, wrote a detailed report about the islands, in which he also gave information about the population.

In 1344 Pope Clement VI founded the Principality of the Happy Islands as a fiefdom of the Holy See . He appointed Luis de la Cerda , a nobleman who came from the royal families of Castile and France, as prince and gave him a golden crown and a scepter. Luis de la Cerda undertook to convert his subjects to the true faith. After he died in 1346 or 1348 without having seen his principality, it was no longer mentioned in any papal document.

When Majorcan believers planned a new beginning of Christianization of the Canary Islands by peaceful means, Pope Clement VI. in addition his blessing and in 1351 founded the diocese of the Happy Islands (Fortunatae Insulae), which was later named Diocese Telde . The peaceful missionary work by Mallorcans and Catalans probably ended in 1393 when locals killed the missionaries in response to predatory attacks by Western European pirates .

Castile takes possession of the islands

In 1402, the French nobles Jean de Béthencourt and Gadifer de La Salle brought the island of Lanzarote under their rule by concluding treaties with the indigenous people. Since their funds were insufficient for the subjugation of other islands, Jean de Béthencourt submitted in 1403 as a vassal of King Henry III. of Castile . In the course of the next few years he succeeded, mostly almost without a fight, to enforce the suzerainty of the Crown of Castile on the islands of Fuerteventura and El Hierro . The occupation of the islands of La Gomera , Gran Canaria , Tenerife and La Palma failed because of the resistance of the inhabitants. There is a report on the process of taking possession with the title Le Canarien , which has come down to us in two versions.

On July 7, 1404, Pope Benedict XIII founded a new diocese for the Canary Islands on the island of Lanzarote , the diocese of San Marcial del Rubicón , without making any reference to the lost diocese of Telde.

In 1418 Maciot de Béthencourt, a relative of Jean de Béthencourt, transferred the claims to rule over the islands to Enrique de Guzmán, Count of Niebla. Over the course of the next few years, the rights passed several times to other people. In 1445 Hernán Peraza (the Elder, 1390-1452) received power over the conquered islands and the claim to the islands still to be conquered. His attempts to conquer the islands of Gran Canaria, Tenerife and La Palma were unsuccessful. At the end of his life, Hernán Peraza had to realize that the company to conquer the densely populated Canary Islands was beyond its economic possibilities. His daughter Inés Peraza de las Casas inherited the rule in 1454. In 1477 the Catholic Kings took over the right to conquer the three large islands Gran Canaria, La Palma and Tenerife again for the Crown of Castile. They compensated the Peraza-Herrera family with five million maravedíes and the right to call themselves Counts of Gomera and El Hierro.

In the course of the War of the Castilian Succession , the Catholic kings tried to reaffirm their claims to a right to trade with Africa. They sent merchant fleets, which consisted of ships from traders from the countries of the Crown of Castile, on voyages that went via the Canary Islands to the coast of Africa in order to exchange goods for gold and slaves. All attempts to establish trade relations between Africa and Castile were prevented by Portugal with military force. The Catholic kings had to realize that they could not break the Portuguese monopoly on the African trade. Therefore, in the Treaties of Alcáçovas , Castile renounced the seafaring south of Cape Bojador and was awarded the guarantee of rule over the Canary Islands and a strip of the African coast between Cape Nun and Cape Bojador. Castilian ships were forbidden to enter South of Cape Bojador. The first voyage of Christopher Columbus therefore took place exactly on this border to the west.

While the Canary Islands were seen mainly as a starting point for trade with Africa in the 14th to 16th centuries, after 1492 they gained importance as a starting point for the development of America. The main reason for this was that the wind and currents from the islands made crossing to America easier than from Europe. Even at the time of steam shipping, the traffic routes ran across the Canary Islands, on which water and coal imported from England could be bunkered before the crossing to America .

Integration of the islands into the kingdoms of the Crown of Castile

In 1478 the Catholic Kings began to enforce their rule over the islands of Gran Canaria, La Palma and Tenerife. Through Capitulaciones , the costs for the conquest were not raised by the crown, but by the conquistadors or by private donors. These should be compensated from the future profits of the conquered territories. After some difficulties, the island of Gran Canaria was subjugated by 1483. In 1493 troops under the command of Alonso Fernández de Lugo conquered the island of La Palma. During the submission of the inhabitants of the island of Tenerife, the troops were defeated by the Guanches in 1494 in the First Battle of Acentejo near today's town of La Matanza de Acentejo . In a new attack in 1495, the invaders' troops won the Battle of Aguere near today's city of La Laguna and the second Battle of Acentejo near today's city of La Victoria. The Guanches surrendered in 1496. During both campaigns of conquest, old Canarians from other Canary Islands and members of the Guanche tribes from the south of the island of Tenerife also fought on the side of the Castilians.

In the following time the Canary Islands developed into part of the Kingdom of Castile or a separate kingdom of the Crown of Castile. In 1494, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria received city rights, as they were common for cities in Castile. The municipal administrations were organized on the Seville model . Castilian law applied. The Old Canarians did not appear as an ethnic minority to be taken into account, as did the Native Americans later. Legal provisions that differed from those applicable on the mainland, such as the temporary right to trade directly with America, were justified by the geographical location.

Canary Islands as an integral part of Spain

During the War of the Spanish Succession , the inhabitants were not dissuaded from their support of King Philip V even by the attack by the English admiral John Jennings on Santa Cruz de Tenerife . Due to their location, the archipelago was hardly affected by the Napoleonic Wars on the Iberian Peninsula against a French takeover in Spain. The “Junta Suprema de Canarias” was formed in La Laguna and was also represented in the Junta Suprema Central on the Spanish peninsula. The Canary Islands, like other parts of mainland Spain, were represented in the Constituent Cortes of Cadiz . When the Kingdom of Spain was redistributed into 49 provinces in 1833, the province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife , which at that time still comprised all of the Canary Islands, was in a row with the provinces of the peninsula . The province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife was, in the elections in the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, apart from the geographically different election date, an electoral district like all other provinces.

During the time of the Second Republic, various statutes of autonomy for the Canary Islands were drafted, but none of them came into force until 1937. During the Spanish Civil War , there was no armed conflict in the Canary Islands. Many supporters of the elected government and opponents of the Francoist coups were interned in camps specially set up for this purpose. Many were murdered or disappeared. During the Second World War, the islands were cut off from almost all economic relations. Both the German Wehrmacht and the Allies had plans to occupy the islands as a base. After Francisco Franco's death , the Spanish Parliament passed a first statute of autonomy (similar to a German state constitution) for the Canary Islands in 1982, as it did for the other Comunidades Autónomas. The "Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias" is today one of the 17 autonomous communities in Spain . On May 30, 1983, the first parliament of the Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias met. May 30th, the Día de Canarias , has been the holiday of the Canary Islands since then.

Migrants from Africa

The islands were and still are approached by migrants from Africa with boats; in doing so they cross the Canary Islands . In 2005 there were 4,751 people, according to the Spanish Ministry of the Interior. In 2006 there were almost 32,000 migrants ( Cayuco crisis); Asian migrants were also apprehended for the first time in September. In 2007 there were around 10,000 illegal migrants. Various measures (such as patrol boats and deportation agreements) reduced the number of refugees to 663 people in 2016.

From January to November 2020, more than 18,000 migrants landed in the Canary Islands; Hundreds of new ones arrive every day. They started in Morocco, Mauritania or Senegal; some set sail in the Gambia, 2,400 km away . The COVID-19 pandemic is seen as a push factor for migration .

Coat of arms and symbols

coat of arms

The coat of arms shows in blue coat of arms two three pole as Asked silver triangles and a triangle in the sign foot , symbolizing the seven main islands. A golden crown rests on the shield, above it in a floating silver band the motto 'Océano' in capitals .

Shield holders are two brown dogs with a blue collar. The pedestal is missing from the coat of arms .

flag

The flag of the Canary Islands was established in 1982 in Article 6 of the Autonomy Statute of the Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias : “The flag of the Canary Islands consists of three equal, vertical stripes. The colors, seen from the flagpole, are white, blue and yellow. "

anthem

A piece entitled Arrorró from Teobaldo Power's orchestral work Cantos Canarios has been the melody of the official anthem of the autonomous community of the Canary Islands since 2003. The text is from Benito Cabrera .

Official symbols

In 1991 the government of the Canary Islands declared the Canary Island Girlitz ( Serinus canaria ) and the Canary Island Date Palm ( Phoenix canariensis ) to be symbols of the Canary Islands.

Government and Administration

Representation of the Canary Islands in Parliament in Madrid (Cortes Generales)

The Spanish Parliament in Madrid ( Cortes Generales ) consists of two chambers: the House of Representatives (350 seats) and the Senate (266 seats).

- House of Representatives: The population of the Canary Islands is represented in the House of Representatives (Congreso de los Diputados) in Madrid by 15 MPs. In the constituency that includes the province of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, eight MPs are elected, in the constituency that includes the province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, seven MPs are elected on a list using proportional representation.

- Senate: In the elections to the Senate, the residents of the islands of Gran Canaria and Tenerife each elect three senators, while those from Fuerteventura, La Gomera, El Hierro, Lanzarote and La Palma each choose one senator in a direct proportional representation. Three other senators are appointed by the Parliament of the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands .

Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands

houses of Parliament

In Article 39 of the Canary Islands Statute of Autonomy from November 2018, the electoral system for electing parliament was reorganized. The first additional article of the statute determines the electoral procedure until a new electoral law comes into force.

- Electoral procedure under the 1982 Statute of Autonomy

The Canary Islands have a unicameral parliament . All Spaniards who are of legal age and who have their primary residence in the Canary Islands are entitled to vote. Parliament is elected in general, direct, equal, free and secret elections. Constituencies are the individual islands. Within these constituencies, the representatives are determined by proportional representation . According to the Statute of Autonomy, Parliament must have 50 to 70 members.

Depending on the number of inhabitants, the islands send different numbers of members to parliament:

- Tenerife and Gran Canaria each 15

- La Palma and Lanzarote each 8

- Fuerteventura 7

- La Gomera 4

- El Hierro 3

In the allocation of seats, only those parties will be considered that have received at least 30% of the votes on the respective island or at least 6% of the votes in the Canaries.

The seat of parliament is in Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

- Parliament since 2015

In the election on May 24, 2015, 931,876 voters out of 1,661,272 eligible voters cast their votes, which corresponds to a voter turnout of 56.1%. A government coalition was formed from Coalición Canaria - Partido Nacionalista Canario (CC-PNC) and PSOE, which results from the following distribution of seats:

| Political party | Seats | proportion of |

|---|---|---|

| PSOE (socialist party) | 15th | 19.53% |

| Partido Popular (PP) (Christian Conservative Party) | 12th | 18.26% |

| Coalición Canaria (CC) (nationalist and liberal regional party) | 16 | 17.65% |

| Podemos | 7th | 14.28% |

| Nueva Canarias (NCa) | 5 | 10.5% |

| Agrupación Socialista Gomera | 3 | 0.55% |

| Coalición Canaria - Agrupación Herreña Independente (AHI-CC) | 2 | 0.27% |

government

The government of the Canary Islands consists of the President (Presidente del Gobierno), the Vice-President and the Ministers (Consejeros).

The President is elected by Parliament. He must be a member of parliament and is appointed by the king after the election. The President appoints and dismisses the Vice-President and the other members of the government. The vice-president must be a member of parliament. The number of government members is limited to eleven.

The seat of the President changes with each legislative period of the parliament. From 2015 to 2019, the seat of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, that of the Vice President Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

- Government since 2015

Fernando Clavijo Batlle of the regional party Coalición Canaria (CC) has been president of the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands since 2015 . After the elections on May 24, 2015, the Coalición Canaria - Partido Nacionalista Canario formed a coalition government with the PSOE:

| Official title (German / Spanish ) | Name (party) |

|---|---|

| Prime Minister Presidente |

Fernando Clavijo Batlle (CC) |

| Vice-President and Minister of Labor, Social Affairs and Housing Vicepresidenta y Consejera de Empleo, Políticas Sociales y Viviendas |

Patricia Hernández Gutiérrez (PSOE) |

| Minister of Economy, Industry, Trade and Economic Relations Consejero de Economía, Industria, Comercio y Conocimiento |

Pedro Ortega Rodríguez (CC) |

| Minister of the Presidential Office, Justice and Equality Consejero de Presidencia, Justicia e Igualdad |

Aarón Afonso González (PSOE) |

| Minister of Finance Consejera de Hacienda |

Rosa Dávila Mamely (CC) |

| Minister of Health Consejero de Sanidad |

Jesús Morera Molina (PSC-PSOE) |

| Minister for Regional Policy, Sustainability and Security Consejera de Política Territorial, Sostenibilidad y Seguridad |

Nieves Lady Barreto Hernández (CC) |

| Minister for Public Works and Transport Consejera de Obras Públicas y Transportes |

Ornella Chacón Martel (PSOE) |

| Minister of Education and Universities Consejera de Educación y Universidades |

Soledad Monzón Cabrera (CC) |

| Minister for Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Water Management Consejero de Agricultura, Ganadería, Pesca y Aguas |

Narvay Quintero Castañeda (AHI-CC) |

| Minister for Tourism, Culture and Sport Consejera de Turismo, Cultura y Deportes |

María Teresa Lorenzo Rodríguez (CC) |

province

In 1927, the province of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, which had existed since 1833 (provinces were usually named after the provincial capital), were divided up, creating a new province of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. There was no higher-level administrative unit in the Canary Islands over these two provinces. The government in Madrid was represented in both provinces by a civil governor .

The Constitution of the Kingdom of Spain from 1978 provides in Article 141 provinces principle as administrative units with a provincial council and its own provincial administration before. In paragraph 4 of the article, however , the formation of island governments (“Consejos” or “Cabildos”) is determined for the “archipiélagos”, ie for the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands. It follows that the division of the Canary Islands into provinces is almost meaningless, as there are no provincial administrations. The provinces continue to be constituencies in elections to the Spanish Parliament ( Cortes Generales ).

The autonomous community of the Canaries consists of two provinces:

| province | Provincial capital | location | map | Islands | coat of arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Las Palmas Province | Las Palmas |

|

|

eastern islands: Gran Canaria Fuerteventura Lanzarote |

|

| Santa Cruz de Tenerife Province | Santa Cruz de Tenerife |

|

|

western islands: Tenerife La Palma La Gomera El Hierro |

|

Cabildo Insular

The 1978 constitution provides for Cabildos Insulares for the Canary Islands as a government, administrative and representative body limited to the individual islands. The Cabildos are elected in general elections.

city

The 1978 constitution guarantees the independence of cities. The town hall (Ayuntamiento) consists of the council assembly (Pleno) and the city government (Junta de Gobierno Local).

The council meeting is sent by general, equal, free, direct and secret ballot. Citizens of the European Union are also entitled to vote in this election if they are registered with their first place of residence in the municipality (so-called residents). The mayor is the chairman of the council assembly (Presidente del Ayuntamiento).

The city government consists of the mayor and his deputies, who must be council members, and other members. The city government (Junta de Gobierno) runs the city administration.

The cities of the Canary Islands are very different in size: from 8.73 km² ( Puerto de la Cruz ) to 383.52 km² ( Pájara ) and from 770 inhabitants ( Betancuria ) to 381,271 inhabitants ( Las Palmas de Gran Canaria ). This results in a very different meaning of the activities of the Ayuntamientos.

Foreign Relations

All major countries in the world are represented by consulates , some of which also have an economic and trade office.

business

The gross domestic product (GDP) of the Canarian economy was around 42.4 billion euros in 2007. Around 71% of this was generated in the service sector (including tourism), followed by construction (4.7 billion), industry and trade (1.7 billion), energy (1.1 billion), and agriculture, livestock and fisheries ( 0.5 billion). In comparison with the GDP per capita in the EU , expressed in purchasing power standards, the Canary Islands achieve an index of 74 (EU-28: 100, as of 2015).

Overall, the Canarian GDP grew by 7.17% from 2006 to 2007.

The islands have branches of the main Spanish and some foreign banks.

People, including non-EU nationals who are registered with their primary residence in the Canary Islands, receive discounts with their registration certificate, such as discounts on inter- island flights and ferries as well as for flights to the Spanish mainland and the Balearic Islands .

Agriculture

Before the advent of mass tourism in the 1960s, the Canaries lived mainly from agriculture, livestock and fishing. Measured in terms of GDP, this branch of the economy plays a comparatively minor role today.

The majority of agricultural production is obtained from the cultivation of bananas; Other noteworthy products are tomatoes, cucumbers, cut flowers, potatoes and wine. But other tropical fruits such as clementines, lemons, papaya and mango are also grown. The total agricultural area in 2006 was 51,867 hectares.

tourism

By far the most important branch of the economy is tourism . The main tourist centers are in Tenerife, Gran Canaria, Fuerteventura and Lanzarote. In 2007, around 14.2 billion euros, or 31.09% of GDP, were turned over in the tourism industry (2006: 13.5 billion). The number of guests fell from 2006 to 2007 by 6.6% to around 9.33 million. The vast majority of tourists come from Great Britain, followed by Germany, the Netherlands and Ireland; Of these, 3,410,165 traveled to Tenerife, 2,713,728 to Gran Canaria, 1,471,979 to Fuerteventura and 1,618,335 to Lanzarote.

In 2012, the number of visitors from mainland Spain fell by around 2.1% due to the economic crisis. Overall, however, with 10,101,493 tourists, there were only 0.4% fewer guests. In 2014 this situation eased again. But the Canary Islands are still visited by 0.7% fewer mainland Spaniards than before the crisis. The trend for cruisers is much more positive: Tenerife alone posted another record in 2014 with 301 ships and 545,000 cruisers. In total, the Canary Islands were visited by 11.4 million foreign visitors in 2014. This corresponds to an increase of 8% compared to the previous year.

Number of tourists by destination

| Island | Tourists |

|---|---|

| Tenerife | 5,729,900 |

| Gran Canaria | 4,189,000 |

| Lanzarote | 2,913,000 |

| Fuerteventura | 1,895,000 |

| La Palma | 258,000 |

| La Gomera and El Hierro | 127,000 |

| total | 15,111,300 |

Industry, construction and energy

The industry focuses mainly on energy and water management, but also on food, tobacco and other light industries . Overall, industrial production fell by 0.3% in 2007 (2006: −1.48%). With a share of 11.2% of GDP, construction ranks second after the service sector. The number of building permits decreased from 2006 to 2007 from 5,053 to 4,012.

Foreign trade

The main trading partner of the Canary Islands is the European Union, and particularly Spain. The Canary Islands' foreign trade deficit was around 14 billion euros in 2007; the largest part of this, around 10 billion, is due to imports from Spain.

Labor market and employment

The unemployment rate was 33.36% in October 2014, tripling it since 2007, but falling by four percent compared to the previous year. At the end of 2013, the number of employees rose by 3.81% and 10,862 people compared to the previous year, which reduced the unemployment rate for the first time since 1997. By 2017 the unemployment rate fell to 23.5%.

Youth unemployment in the Canary Islands is the highest in Europe. In 2013, it was around 70 percent among 16 to 24-year-olds. Around 44,000 young people were no longer registered in the employment offices of the two provinces due to the lack of prospects. Many are trying to gain a foothold abroad, mainly in Germany and South America.

According to the National Statistics Office (INE) , the gross monthly salary of a worker in the Canary Islands in 2006 averaged 1,300 euros, making it the second lowest in Spain. In addition, a Canarian employee has the third longest working hours in the country with an average of 146.1 hours per month. In 2005, the autonomous region of Canary Islands had the second highest increase in the unemployment rate in Spain.

Special tax regulations

The special zone ZEC ( Zona Especial Canaria ) has existed since January 2000 , which was initially approved by the European Union until December 31, 2008, and was extended by the EU into 2019 in January 2007. This organization, founded by the Spanish central government and the regional government and affiliated to the Spanish Ministry of Economy, has the task of promoting and expanding the economic and social development of the archipelago so that it does not only depend on the predominant economic sectors of tourism and construction. This is why there are so-called ZEC companies that commit to certain investments and job creation, and can thus benefit, for example, from a reduced rate of Spanish corporate tax of only four percent (normal in Spain 30%). On the islands of Gran Canaria and Tenerife a minimum investment of 100,000 euros and the creation of five jobs are required, on the other islands with a lower economy it is 50,000 euros and three new employees. One of the main tasks of the ZEC is to attract foreign capital to the Canary Islands. More than 78% of the investments in the low-tax area come from abroad, including over 13% from Germany, making it the largest investor among the approved ZEC companies after Spain.

In the law on the economic and tax regulations of the Canary Islands of July 22, 1972, a value added tax different from the mainland was introduced. This different tax was retained even after Spain joined the EU. After the change in 2019, there are seven different tax rates:

- Tipo cero = 0% This rate applies, among other things, to all types of bread and unprocessed foods (fruit, vegetables, meat, fish, milk and cheese, eggs), cooking oil, pasta, electrical energy, water supply, medicines used in human medicine, books, Newspapers, magazines.

- Tipo de gravamen reducido del 2.75 por ciento = 2.75% This rate applies to renovation work on certain houses.

- Tipo de gravamen reducido del 3 por ciento = 3% This rate applies, among other things, to the manufacture, transport and distribution of electrical energy and gas, textiles and shoes, paper and paper products, and veterinary medicines.

- Tipo general del 6.5 por ciento = 6.5% This rate applies to all income that is not covered by separate regulations of the law. It is the normal tax rate.

- Tipo incrementado del 9.5 por ciento = 9.5% This rate applies, among other things, to work when loading ships and aircraft.

- Tipo de gravamen incrementado del 13.5 por ciento = 13.5% This rate applies, among other things, to cigars that cost more than € 1.80 per piece and for various alcoholic beverages, rifles and hunting ammunition, pearls and precious stones.

- Tipo de gravamen incrementado del 20 por ciento = 20% This rate applies to tobacco products except cigars.

Small businesses with a turnover of less than € 30,000 per year are exempt from tax. In addition, other tax rates apply in the Canary Islands, including mineral oil tax, tobacco tax and spirits tax. Inheritance tax is regulated differently in all autonomous communities.

Infrastructure

The archipelago is around two hours by plane from the Iberian Peninsula and around four hours by plane from Central Europe. There are direct flights to the main cities in Spain, Europe and Latin America. Each island now has its own airport :

- Tenerife North Airport

- Tenerife South Airport

- Gran Canaria Airport

- La Palma airport

- Lanzarote Airport

- El Hierro Airport

- La Gomera Airport

- Fuerteventura airport

While the airports of La Gomera and El Hierro only handle inter-island flights, the other islands have international airports. The airports in Tenerife South and Gran Canaria are among the busiest in Spain. The islands are connected to one another by numerous airlines . These are mainly taken over by the Canarian airline Binter Canarias based in Telde on Gran Canaria . Another Canarian airline founded in 2001 was Islas Airways , which ceased operations in 2012.

Ferries operate between the islands , including those operated by the Fred shipping company . Olsen Express , Compañía Trasmediterránea and Naviera Armas .

There was already a tram in Tenerife from 1904 to 1959. Since March 2007, the only rail-based means of transport in the Canary Islands has been running again a tram, the Tranvia Tenerife, between the capital Santa Cruz and the university town of La Laguna . A railway line between Santa Cruz and Adeje is also being planned.

Power supply

Electricity generation on the individual Canary Islands is self-sufficient. A grid or power connections between the islands do not exist. Preparatory work is underway between Tenerife and La Gomera for the installation of an undersea cable to improve the efficiency and reliability of the electricity supply on both islands. The water depth of the submarine cable is 1200 meters in some sections.

The largest share of the power supply on the islands is provided by fossil power plants , each of which consists of a large number of diesel generators, steam and gas turbines. In line with the increase in population and tourism on the islands, the demand for electricity increased, which had to be gradually compensated for by additional electricity generators. There are 23 power generators at two power plant locations on Tenerife with a total installed output of 1,018 MW. The installed power plant capacity on La Palma consists of 11 fossil-fueled electricity generators with a total of 105 MW as well as wind power and photovoltaic systems with 7 MW and 5 MW respectively. In contrast, the peak consumption value on La Palma in 2015 was 43.4 MW.

The total share of renewable energy generation from wind and solar systems in the Canary Islands was 7.8% in 2016, which was increased to 20% in the following three years with 280 MW of additional installed capacity. The highest share of renewable energy in the electricity supply is achieved on El Hierro, which was 56.7% in 2018 with 25.0 GWh, compared to fossil energy with 19.2 GWh (43.3%). The proportions of energy fluctuate greatly depending on the weather. The monthly maximum value of renewable energy was 95.4% in July 2018 and the minimum value was 24.7% in October.

Power supply systems in the Canary Islands:

| Name / place | Type of generators | Installed capacity (MW) | Annual output (GWh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tenerife | |||

| Central térmica de Granadilla | 14 diesel, steam and gas turbines | 797 | 2,811 (2015) |

| Central térmica de Caletillas | 3 diesel, 6 steam and 2 gas turbines | 431 | |

| Parque Eólico de Arico | 8 wind turbines | 18.8 | 30.7 (2018) |

| Parque Eólico Punta de Teno | Wind turbines | 1.8 | 7.5 (2018) |

| Parque Eólico PE Granadilla I | Wind turbines | ||

| Parque Eólico PE Granadilla II | 7 Siemens wind turbines | 18.3 | |

| Parque Eólico PE Granadilla III | Wind turbines | 9.9 (2018) | |

| All wind farms on Tenerife | 186.7 (2019) | ||

| La Palma | |||

| Los Guinchos | 10 diesel / 1 gas turbine | 108 | |

| Garafía | 2 wind turbines | 1.6 | |

| Faro Fuencaliente | 3 wind turbines | 2.7 | 10.8 (2018) |

| Manchas Blancas, Mazo | 3 wind turbines | 1.8 | 5.6 (2018) |

| Aeropuerto La Palma | 2 wind turbines | 1.32 | |

| 4 photovoltaic fields | 2.8 | ||

| El Hierro | |||

| Central de Llanos Blancos | 9 diesel | 15th | 19.2 (2018) |

| Gorona del Viento | 5 wind turbines | 11.5 | 25.0 (2018) |

| pumped storage power plant | 4 water turbines | 10 | |

| La Gomera | |||

| El Palmar, San Sebastian | 10 diesel generators | 23 | 74.1 (2017) |

| Vallehermoso | Wind turbines | 0.4 | |

| Gran Canaria | |||

| Barranco de Tirajana | Diesel / 2 gas turbines | 697 | |

| Jinamar , Las Palmas | 5 diesel / 3 gas turbines | 415.6 | |

| Piletas 1, Agüimes | Wind turbines | 12.8 | |

| Balcon de Balos, Agüimes | Wind turbines | 9.2 | |

| La Vaquería, Agüimes | Wind turbines | 2.35 | |

| Montaña Perros, Agüimes | Wind turbines | 2.3 | |

| Triquivijate, Agüimes, Agüimes | Wind turbines | 4.7 | |

| Vientos del Roque, Agüimes | Wind turbines | 4.7 | |

| Doramas, Agüimes | Wind turbines | 2.3 | |

| La Sal, Telde | Wind turbines | 2 | |

| La Sal III, Telde | Wind turbines | 2 | |

| Haría, Agüimes, Santa Lucía and San | Wind turbines | 2.35 | |

| Bartolome de Tirajana | Wind turbines | ||

| All wind farms in Gran Canaria | 45 | ||

| Fuerteventura | |||

| Las Salinas, Puerto del Rosario | 9 diesel / 3 gas turbines | 187 | |

| Renovable II, La Oliva | 2 wind turbines | 4.7 | 14th |

| Tablada, Tuineje | Wind turbines | 6.4 | |

| Moralito, Tuineje | Wind turbines | 9.2 | |

| All wind farms on Fuerteventura | 20th | ||

| Lanzarote | |||

| Central térmica de Punta Grande | 10 diesel and gas turbines | 231 | |

| Parque Eólico Teno, Los Valles | Wind turbines | 7.6 | 24.5 (2018) |

| All wind farms on Lanzarote | 23.43 | ||

| All wind farms in the Canary Islands | |||

| 2007 | 59.9 | ||

| 2008 | 158.3 | ||

| 2016 (7.8% wind and solar share) | |||

| 2019 (20% wind and solar share) | 417.6 |

Culture

Through centuries of cultural exchange , the archipelago is characterized by a mixture of the cultures of the Guanches , Berber groups , European colonial rulers and the customs that were brought to the islands by merchant shipping, mainly from the American continent. There are numerous archaeological sites, the finds of which can be seen in ethnographic and anthropological museums. The whistling language El Silbo , which the indigenous people of the Canary Islands developed and which is now being taught again in schools on La Gomera, is unique .

Historical and artistic monuments express the Canarian identity through their architecture, sculpture and painting. The works of the artist and conservationist César Manrique from the island of Lanzarote should be mentioned here in particular . The traditions include festivals with typical costumes and Canarian folklore in the individual villages, where the typical string instrument of the Canaries, the timple , is important. Religion and pagan rites of the indigenous people intermingle. This includes the Latin American-inspired carnival with samba rhythms and many colors as well as cockfighting and the Lucha Canaria wrestling match .

kitchen

Canarian cuisine is strongly based on Spanish , with various influences. Potatoes and legumes serve as the basis of the often simple dishes.

media

It has its own public radio and television company , TV Canaria , based in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, as well as the radio station Radio ECCA and the daily newspapers Canarias7 , Diario de Avisos , El Día , La Opinión de Tenerife and La Provincia .

The Canary Islands are an important communication hub between Europe, Africa and America - this is where the highest density of overseas cables can be found in the world.

education

The Canary Islands have two state universities, the University of La Laguna and the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria , to which various distance learning centers are connected. The University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria was formed in 1989 from parts of the Universidad Politécnica de Canarias, which existed from 1979 to 1989, and some locations of the University of La Laguna; it is mainly oriented towards technology, economics and administration, while the natural sciences are concentrated in La Laguna.

There are also two private universities: the Universidad Europea de Canarias (UEC) in La Orotava on Tenerife is the oldest private university in the archipelago. The Universidad Fernando Pessoa-Canarias on Gran Canaria primarily offers courses for media and health professions.

literature

General

- Richard Pott , Joachim Hüppe, Wolfredo Wildpret de la Torre: The Canary Islands. Natural and cultural landscapes. Ulmer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-8001-3284-2 (illustrated representation of geobotany ).

story

- Martial Staub: The 'rediscovery' of the Canary Islands. In: Andreas Speer , David Wirmer: 1308. A topography of historical simultaneity (= Miscellanea Mediaevalia. Volume 35). De Gruyter, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-021874-9 , pp. 27-38.

- Wolfgang Reinhard: The submission of the world . Global history of European expansion 1415–2015 (= historical library of the Gerda Henkel Foundation ). CH Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-68718-1 , p. 1648 .

- José Manuel Castellano Gil, Francisco J. Macías Martín: The history of the Canary Islands . Ed .: C. Otero Alonso. 7th edition. Centro de la Cultura Popular Canaria, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 2012, ISBN 978-84-7926-115-3 (translator Ernesto J. Zinsel).

- Antonio de Béthencourt Massieu (ed.): Historia de Canarias . Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 1995, ISBN 84-8103-056-2 (Spanish).

- José Juan Suárez Acosta; Félix Rodrígez Lorenzo: Carmelo L. Quintero Padrón: Conquista y colonisación . Centro de la Cultura Popular Canaria, La Laguna 1988 (Spanish, Conquista y colonisación [accessed June 20, 2016]).

- Luis Suárez Fernández: La conquista del trono (= Forjadores de história ). Ediciones Rialp, SA, Madrid 1989, ISBN 84-321-2476-1 (Spanish).

Flora and fauna

- Peter Schönfelder , Ingrid Schönfelder: The Kosmos-Canary Islands flora. Over 850 species of the Canary Islands flora and 48 tropical ornamental trees. Franckh-Kosmos, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-440-06037-3 .

- Martin Wiemers: The Butterflies of the Canary Islands. - A Survey on their Distribution, Biology and Ecology (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea and Hesperioidea). In: Linneana Belgica. Vol. 15, 1995, pp. 63-84, 87-118 ( online ).

geology

- Peter Rothe: Canary Islands (= collection of geological guides. Volume 81). Gebr. Bornträger, Berlin / Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-443-15081-5 .

- Kaj Hoernle, Juan-Carlos Carracedo: Canary Islands Geology. In: Rosemary D. Gillespie, David A. Clague: Encyclopedia of Islands. University of California Press, Berkeley CA 2009, pp. 133-143, ISBN 978-0-520-25649-1 (PDF; 8 MB) .

- Juan Carlos Carracedo, Simon Day: Canary Islands (= Classic Geology in Europe. Volume 4). Terra, Harpenden 2002, ISBN 978-1-903544-07-5 .

- Vicente Arana, Juan C. Carracedo: Los Volcanes de las Islas Canarias. Editorial Rueda, Madrid 1978–1979, ISBN 84-7207-011-5 (for the complete works).

- Volume I: Tenerife.

- Volume II: Lanzarote y Fuerteventura.

- Volume III: Gran Canaria.

- Volume IV: Gomera, La Palma, Hierro.

Culture

- José Carlos Delgado Díaz: The Folk Music of the Canaries. Publicaciones Turquesa, Santa Cruz de Tenerife 2004, ISBN 84-95412-29-2 .

Web links

- Gobierno de Canarias. Website of the regional government (Government of the Autonomous Community of Canarias).

- Maps of the Canary Islands based on satellite images (interactive)