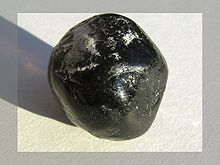

Obsidian

Obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic rock glass .

etymology

The name is derived from the Roman Obsius, who is said to have brought the first obsidian from Ethiopia to Rome in ancient times .

Emergence

Obsidian is formed when lava cools rapidly with a mass fraction of water of a maximum of 3–4%. With higher contents of volatile substances (in addition to water mainly CO 2 ), the rock would otherwise expand into pumice , even if it cooled down quickly . Pechstein is formed when it cools down slowly . The formation of volcanic glasses depends to a large extent on the viscosity and therefore on the silica content (the higher, the more viscous) of the lava.

Due to the rapid cooling, regular crystal structures do not form . The glass from which the obsidian is made thus has a chaotic, amorphous structure.

Like all glasses, obsidian is metastable and shows a tendency to devitrify and crystallize within geological time . In this way, too, the formation of spherulites is possible, these are mineral aggregates made of crystals arranged in rays (ocular obsidian). With the exception of pitchstone, volcanic glasses are unknown from the Paleozoic and Precambrian because they are completely devitrified today .

Most obsidians have a silica content of 70% and more and belong to the rhyolite family ( rhyolites are the volcanic equivalents of granites ). Trachitic , andesitic and phonolithic (lower silicic acid content ) obsidians are rarer .

nature

The color varies greatly depending on the presence of various impurities and their oxidation states. Despite the mostly high content of silica (for comparison: granites are usually light-colored rocks), obsidian is mostly dark green to black in color, occasionally also brown and reddish. This is due to the finely distributed hematite or magnetite minerals in the rock .

Depending on the occurrence, however, more or less large quantities of crystals can be embedded in the glassy ( hyaline ) structure. The flowing texture that is often developed is expressed in a streaky image (eutaxitic structure).

The hardness is 5.0 to 5.5 on the Mohs scale.

Varieties

Snowflake obsidians contain inclusions of radially grown structures up to 1 cm in size, so-called spherulites. These minerals , mostly feldspars or cristobalite (a high-temperature modification of quartz), grew spherically from a crystallization nucleus into the surrounding melt, until the cooling stopped this process.

Small clumps of obsidian rounded by erosion are called Apache tears (also known as smoky obsidian ). Popular belief has it that an Indian died where an Apache tear was found.

Occurrence

So far, around 40 obsidian sites are known worldwide (as of 2019), among others

in Africa :

- Canary Islands : at Pico del Teide on Tenerife as well as on the edge of the Caldera de Taburiente and in the mountains on La Palma

in the Middle East :

- Armenia : Aragazotn , Kotayk and Sevan (near the city of the same name )

- Turkey : Kars (including near Sarıkamış )

in East Asia :

- China : Huangnishan Clay Deposit in Xuyi County, Jiangsu Province and Fuxin, Liaoning Province

- Indonesia : Bali

in Europe :

- Germany : various quarries near Baden-Baden , (Baden-Württemberg)

- Greece : the islands of Nisyros and Milos in the southern Aegean

- Iceland : the obsidian cliff on Hrafntinnuhryggur mountain and the Hrafntinnusker –Reykjadalir nature reserve in the Rangárvallasýsla district

- Italy : Marrubiu and Skala Antruxioni, Pau in the province of Oristano (Sardinia); Lipari and Pantelleria islands (Sicily region; Cava Val di Serra quarry ( Ala municipality , Trentino province))

- Portugal : Lake Furnas , Azores

- Slovakia : Merník, Okres Vranov nad Topľou

- Hungary : Tolcsva in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén County

in North America :

- Canada : Mount Edziza in northern British Columbia , obsidian trade since 8000 BC Chr.

- USA : Yellowstone National Park area , Wyoming ; Newberry Caldera and Glass Buttes , Oregon ; Big Glass Mountain , California; Hualālai volcano , Hawaii

- Mexico : Alamos in the state of Sonora

in South America and Polynesia :

- Peru : Macusani uranium deposit, Carabaya province

- Chile : Maunga Orito on Easter Island

- New Zealand : Mount Tarawera and Mayor Island / Tuhua , North Island

use

As a raw material

In the Stone Age , especially from the Neolithic , obsidian was valued as a material for tools, just like flint because of its sharp-edged, shell-like break and its glassy structure . Its Mediterranean occurrence is known and the distribution of the obsidian can be proven over long distances (more than a hundred kilometers).

Europe

There are few obsidian deposits in Europe. The main deposits used during the Stone Age of Southern Europe are the Aeolian Islands , but also Monte Arci , Palmarola and Pantelleria . They were already discovered before the 5th millennium BC. Permanently settled. Ten other small deposits used in the Stone Age were in Eastern Europe.

Asia

In the Hittite Empire, vessels were made from obsidian. In ancient Rome , cut and polished obsidian was used as a mirror. The Assyrians obtained obsidian ( NA 4 ZÚ, ṣurru) from the Nairi countries in northeastern Turkey, among others . It is documented as a tribute under Tiglat-pileser I.

America

In the prehistoric Mexican city of Teotihuacán , obsidian was processed into figures of gods and other sculptures. The stone is used both in the black form and as "silver obsidian" or "gold obsidian". This particular form of obsidian appears black in the shade, while it shines bright gold or silver in the light. When processed, the stone is matt and light gray. It only develops its shine through polishing. The Aztecs, as well as other Mesoamerican peoples, used obsidian to make spear and arrowheads and complete swords called maquahuitl .

Modern times

With the increasing spread of bronze , the use of obsidian declined in Europe and Asia. Today obsidian is mainly used for the production of art objects and as a gem , sometimes also for knife blades. Proposals to make medical scalpels from them have not caught on; there are no products approved for this purpose.

Dating and origin

The thickness of the hydration layer on prehistoric artifacts is used for dating. Since the origin of the obsidian can be determined on the basis of the admixture of trace elements or the isotope composition ( neutron activation analysis ) and the age (fissure trace analysis ), obsidian artifacts can also provide important information about prehistoric exchange or trade .

Forgeries and mix-ups

Since obsidian occurs in relatively large quantities as a gemstone, and its price is therefore comparatively low, it is rarely counterfeited. It is also easy to identify by its typical glass luster. Black obsidian can be confused with black Schörl (tourmaline group) and onyx (or colored agate ) if it is not transparent. All other obsidian variants are unmistakable due to their characteristic patterns and play of colors.

Obsidian can easily be confused with impact melt rocks . These are caused by the melting and rapid cooling of rocks as a result of a meteorite impact . Pechstein is very similar to obsidian in appearance and formation.

literature

- Walter Maresch, Olaf Medenbach: Rocks. (= Steinbach's nature guide ). New, edited special edition. Mosaik-Verlag, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-576-10699-5 , p. 90.

- Albrecht German, Ralf Kownatzki, Günther Mehling (eds.): Natural stone dictionary. 5. Completely revised and updated new edition. Callwey, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-7667-1555-0 , p. 262.

- Hans-Otto Pollmann: Obsidian Bibliography. Artifact and provenance (= publications from the German Mining Museum. 78 = The cut. Supplement 10). Publishing house of the German Mining Museum, Bochum 1999, ISBN 3-921533-67-8 .

See also

Web links

- Mineral Atlas: Obsidian

- Explanation of the Zemplén obsidian, with good pictures

- Worldwide obsidian distribution, not quite complete

- Maya and Olmec Obsidian (en)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Robert Howard Tykot: Prehistoric trade in the Western Mediterranean: The sources and distribution of Sardinian obsidian . (PDF) Thesis to the department of Anthropology, Harvard University, Cambridge October 1995, p. 53, accessed February 17, 2016.

- ^ Mineral Atlas : Obsidian

- ↑ Benno Plöchinger: The Transcaucasian Armenia, part of the Alpine Mediterranean Orogen . In: Verh. Geol. B.-A. Year 1979, Issue 2, 1979, p. 195–203 ( PDF on ZOBODAT [accessed August 5, 2019]).

- ↑ Mucip Demir: Sarıkamış Obsidian Sources and Evaluation . In: Kafkas Universitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi . tape 19 , 2017, p. 119–139 , doi : 10.9775 / kausbed.2017.008 (Turkish).

- ↑ Olwen Williams Thorpe, Stanley E. Warren, John G. Nandris: The distribution and provenance of archaeological obsidian in Central and Eastern Europe. In: Journal of Archaeological Science 11, No. 3, 1984, pp. 183-212.

- ↑ Olwen Williams Thorpe: A study of obsidian in prehistoric central and Eastern Europe, and it's trace element characterization - An analytically-based study of archaeological obsidian in Central and Eastern Europe, an investigation of obsidian sources in this area, and the characterization of these obsidians using neutron activation analysis. .

- ↑ Corinne N. Rosania, Matthew T. Boulanger, Katalin T. Biro, Sergey Ryzhov, Gerhard Trnka, Michael D. Glascock: Revisiting Carpathian obsidian. In: Antiquity 82, No. 318, December 2008.

- ↑ Betina Faist : The long-distance trade of the Assyrian Empire between the 14th and 11th centuries BC Chr. (= Old Orient and Old Testament. Vol. 265). Ugarit-Verlag, Münster 2001, ISBN 3-927120-79-0 , p. 43 (also: Tübingen, Universität, Dissertation, 1998).

- ↑ Andreas Kalweit, Christof Paul, Sascha Peters, Reiner Wallbaum: Handbook for Technical Product Design. Material and production, decision-making bases for designers and engineers. 2nd, edited edition. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-02641-6 in Google Book Search.

- ^ BA Buck: Ancient technology in contemporary surgery. In: The Western journal of medicine. Volume 136, Number 3, March 1982, pp. 265-269, PMID 7046256 , PMC 1273673 (free full text).

- ↑ JJ Disa, J. Vossoughi, NH Goldberg: A comparison of obsidian and surgical steel scalpel wound healing in rats. In: Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Volume 92, Number 5, October 1993, pp. 884-887, PMID 8415970 .