Polynesia

Polynesia (from ancient Greek πολύς polýs "much" and νῆσοι nēsoi "islands") is both a large Pacific island region and the easternmost of the cultural areas of Oceania . With an area of almost 50 million km², it is the largest island region in Oceania. Around six million people live on the land area of around 294,000 km², of which New Zealand has the largest share with around 91%.

Concept history

The name Polynesia was first used in 1756 by the French scholar Charles de Brosses , who used this name to refer to all the islands in the Pacific Ocean. In 1831, the French Rear Admiral Jules Dumont d'Urville , at a lecture to the Geographic Society of Paris, proposed a restriction of the term and introduced the terms Micronesia (Greek small islands ) and Melanesia (Greek black islands ) for parts of the Pacific island kingdom. He justified this with the ethnic conditions, which allowed the name Polynesia only for parts of the Pacific settlement area. This division of Oceania into three different regions has remained anchored in common parlance to this day. The Polynesian languages play an important role in this classification.

geography

Polynesia with its many islands and archipelagos stretches from the Hawai'i Islands ( USA ) in the north to New Zealand in the southwest and Easter Island ( Chile ) in the southeast. In the west runs the border between the ( Micronesian ) Gilbert Islands and Tuvalu . This sea area is also called the " Polynesian Triangle ". It covers a sea area of around 50 million km². The Polynesian Islands have a total land area of around 294,000 km², with New Zealand alone being 270,534 km². The distances between the various islands and archipelagos are often several thousand kilometers. The vastness of the ocean is the defining element of Polynesian geography.

With the exception of New Zealand, which was part of the Antarctic many millions of years ago (see also: Geology of New Zealand ), the islands of Polynesia are of volcanic origin, with some volcanoes still active. At the places where the volcanoes have reached close to the sea surface since the last ice age , when the sea level was about 100 m lower, coral reefs formed and with rising sea level hundreds of small and tiny coral islands, varying in size, formed in usually arranged in the form of atolls . Such coral islands often rise only a few meters above sea level.

The habitability of some of these atolls is now endangered by the rapid rise in sea levels caused by the warming of the global climate. Particularly during storm surges, not inconsiderable amounts of salty seawater penetrate the interior of the country and contaminate the drinking water required for the cultivation of crops. It is to be expected that some of these atolls will have to be abandoned in the foreseeable future, as they are no longer suitable for human habitation.

The medium-sized islands and the few large islands are also located on volcanic elevations in the approximately 4000 m deep Pacific Ocean . Some volcanic craters have been raised by geological processes, so that the limestone that was once formed in the shallow sea is now above the surface of the sea , creating a limestone island. There is currently no discernible threat to such islands from rising sea levels.

The equatorial Pacific current , which flows through Polynesia from west to east, is the equatorial countercurrent . To the north, at the height of Hawaii, the North Equatorial Current flows from east to west and to the south, also from east to west, the South Equatorial Current . This is fed by the cold Humboldt Current on the west coast of South America and partially merges into the East Australian Current , which flows along the east coast of Australia and meets New Zealand. From there an eastward current runs to South America, which is composed of warm equatorial water and cold water of the Antarctic circumpolar current , which runs south of Australia and New Zealand . As a result, New Zealand is surrounded by both a warm and a cold ocean current.

A tabular listing of the Polynesian islands and island groups can be found at the end of this article (see table of Polynesian islands ).

population

The total population of Polynesia is estimated to be around six million people today, including approximately one million Polynesians. Except in New Zealand and Hawaii, it is largely homogeneous Polynesian, but numerically very unevenly distributed.

Outwardly, these differ from the rest of the Oceanians in that they are lighter in skin color, have smoother hair and are taller. In the course of the extensive colonization of the Polynesian sea area by the European powers and the United States of America in the 19th and early 20th centuries, there was massive immigration of foreign settlers , migrant workers and slaves from many countries. This leads to a mixed picture of the ethnic composition of the Polynesian population today.

On some islands the proportion of inhabitants of originally Polynesian descent is only extremely small - for example on Hawaii: Here the Polynesian population is just 6.5% - while on other island groups the Polynesians are still in the absolute majority such as Tonga , where 98% of the population are of Polynesian descent. Most of the foreign population has its roots in Asia ( China , Japan , India , the Philippines , etc.), followed by residents of European and American ancestry.

Socio-cultural development of the population

Since the Polynesian triangle extends over a very large sea area, in which many of the different archipelagos are thousands of kilometers apart, there has never been a uniform social or political development in the Polynesian islands. After the arrival of the Europeans in the late 18th and 19th centuries and the subsequent colonization of the region, these differences in the political and economic development of the region became even more differentiated.

Today, in addition to economically and politically highly developed regions, in which Western standards apply to both education and culture, there are also archipelagos whose inhabitants continue to practice economic and social practices that were essentially used in the region thousands of years ago. There are still dependent areas of former European and American colonies, which are now accorded an upgraded status as overseas territories or federal states, alongside independent small kingdoms , small, democratically governed independent states and often dependent areas in which the old traditions are still maintained .

A picture of the cultural, economic and political state of the region that is even remotely uniform cannot therefore be drawn. The differences are too great, there is no common development. The only exception to this is that in the entire Polynesian cultural area among the indigenous population strata a return to former common cultural values and ways of thinking has begun in recent years. This movement is becoming increasingly important throughout Polynesia, demanding recognition and, in many cases, returning old rights and lost property titles. But here, too, there are different local orientations and objectives, which depend on the respective local conditions. In order to gain a more comprehensive picture of the social and political development in modern Polynesia, the individual regions and archipelagos must be considered separately. The list of the states and archipelagos of Polynesia at the end of the article contains links that lead to their descriptions with local peculiarities.

history

First settlement

The Polynesian triangle represents one of the largest contiguous settlement areas on earth. The way and the time frame of the settlement of Polynesia by its original inhabitants has not yet been conclusively clarified. An unequivocal clarification will probably no longer be possible, since many testimonies of the old Polynesian culture have been irretrievably lost.

- According to a theory by the archaeologist Peter Bellwood , around 1500 BC they invaded Seafarers from Taiwan via the Philippines into the area of the island triangle Tonga / Fiji / Samoa and spread relatively quickly over the islands. This theory is based on the development of plant cultivation in the area and the emergence of a certain type of ceramics (so-called Lapita ware ) and is called "express train to Polynesia".

- Other historians suspect a settlement from Melanesia ("Slow Boat to Polynesia"), after which around 1300 BC. The Fiji Islands were reached. From there it spread further east via Samoa and Tonga to the Chilean Easter Island . Recent radiocarbon dates on the island of Rapa Iti have shown that the settlement from Fiji via Tonga and Samoa to the Easter Island region lasted about 1500 years. Accordingly, the first settlers came here around 1200 AD and initially found excellent living conditions so that they could multiply.

- The ethnologist Thor Heyerdahl has shown that a settlement of Polynesia would theoretically also have been possible from the east. In 1947 Heyerdahl advanced from South America to the Polynesian Tuamotu Archipelago with the Kon-Tiki , a raft made of balsa wood , as built by the indigenous people of Peru on the west coast of South America . According to the researcher, the Humboldt Current and the prevailing winds favored sea traffic from east to west. Therefore a settlement from the east is likely. Heyerdahl, however, did not provide sufficient anthropological evidence for his theses. In 2012, genetic studies for Easter Island indicate a (very little) early influence from South America. Genetic analyzes published in 2020 show contact between South Americans and residents of the southern Marquesas Islands between 1150 and 1230. An initial colonization of Polynesia from the American continent is still considered extremely unlikely.

- A view shared by many scientists in recent years is that as early as 4000 BC Seafaring peoples from Southeast Asia, the so-called Austronesians , began to spread steadily towards the east over the archipelagos of the western Pacific. About the Solomon Islands they would have around 1100 BC. BC Tonga and Samoa reached. Due to a steadily growing population and the resulting conflicts over settlement land, groups of them would have moved further and further east and would have by 300 BC. Reached the Marquesas Islands. It is postulated that the further settlement of the Polynesian triangle from then on had its starting point on the Marquesas: It is assumed that the Polynesians reached Easter Island from there around AD 300, reached Hawaii around AD 400 and around Gained a foothold in New Zealand in 1000 AD .

- In a more recent research approach , the genetic drift in pigs is examined for its spread. Researchers led by Keith Dobney from Oxford University concluded from studies on living pigs as well as the excavated remains of dead pigs that the domestic pigs of the settlers came from what is now Vietnam . From there they moved with the residents via Flores and Timor and then spread out in two different routes. A northern one ran across the Philippines and the southern one in the direction of Polynesia. Only there was there a mixture with the Lapita culture.

Until recently, no further scientific evidence could be provided for any of these assumptions that could adequately support or refute one or the other theory. Neither the comparison of languages and dialects, the investigation of ethnic peculiarities of the population groups, the classification of the few archaeological finds, nor the attempt to infer the exact paths of settlement based on the occurrence of the useful plants and animal populations introduced by humans into this habitat were unambiguous There is evidence for either theory or the other.

It was not until 2008 that a team led by Jonathan Friedlaender published a study based on human genetic analyzes that provided evidence that colonization over Melanesia appeared unlikely. The study examined genetic samples from a thousand people from 41 Pacific populations for the existence of 800 markers . It was determined that there are hardly any signs of intermingling with Melanesians among the Polynesians, as would be likely on a migration through Melanesia.

In October 2008, the Lapita expedition set out from the Philippines with the aim of following the Polynesian settlement route with catamarans based on historical models and using the navigation methods of the Polynesians . The route led from the Philippines over the Indonesian Moluccas Islands, along the north coast of New Guinea , through the Solomon Islands archipelago to the islands of Tikopia and Anuta , where the two catamarans were given as gifts to the local population. The trip of 4,000 nautical miles was completed in six months despite difficult weather conditions. The theory that Polynesia could have been settled from the Asian region was thus somewhat supported.

Outside influences

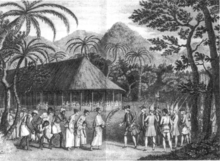

The first Europeans who explored the Polynesian archipelago more closely were the English explorer Samuel Wallis in 1767, the Frenchman Louis Antoine de Bougainville in 1768 and James Cook in 1769. Especially the reports of James Cook and the explorers who wrote him on his three Accompanied trips to the South Seas (including Johann Reinhold Forster and Georg Forster ), drew Europe's attention to the region. Soon afterwards, the first European explorers were followed by a large number of traders, adventurers and the so-called beach walkers , with disastrous consequences for the Polynesian natives: the invading Europeans and Americans were looking for new trade routes, for skins, valuable woods, etc. a. Raw materials. They showed little respect or interest in getting to know and preserving the thousands of years old Polynesian culture. They also brought in infectious diseases that were previously unknown in the region and against which the Polynesians had no immune defense. A large part of the population fell victim to these diseases within a short time. Another part was systematically decimated when slave traders haunted the islands in the wake of European merchants.

Soon the first Christian missionaries came to Polynesia. On many islands they waged a bitter struggle against inherited cultural and religious beliefs. In many places they allied themselves with the ruling families, destroyed the temples and pushed back the practice of indigenous rituals, dances and chants.

The first political upheavals occurred shortly thereafter: the leading seafaring nations in Europe and later also the United States of America recognized the military weakness of the peoples of the region and began to annex island by island and incorporate their colonial empires. In the end, Tonga was the only Polynesian nation that was never a colony.

However, expeditions were also carried out in these regions to discover both sea routes and land and to study the way of life of the inhabitants. There were scientists on the ships who studied both the customs and the language of the Polynesians with seriousness and curiosity. The German poet Adelbert von Chamisso (1781–1838) was one of the first to describe parts of Polynesia (including Hawai'i) and the peoples living there in German. He was a participant in the Russian Rurik expedition under Captain Otto von Kotzebue , which visited and mapped several hundred islands. We owe a large part of our knowledge of the original life of a culture to researchers like Cook or Chamisso, whose roots have now largely been lost.

Influence on nature

The colonization by the Polynesians led to a first wave of extinction for the flora and fauna of the affected islands. The moas and many other New Zealand species were extinct before the arrival of European explorers and are only known to us through bone finds. The same happened to the Moa Nalos in Hawaii . The European settlers then caused a second wave of extinction.

Culture

Although many of the Polynesian islands are separated from each other by thousands of kilometers of open sea and the mutual contact between the inhabitants of distant archipelagos was often interrupted for centuries, the archipelago is regarded as a cultural area that is essentially common . This begins with the languages that have considerable similarities, leads through the similar religious ideas and the similarity of the social structures to closely related methods in agriculture , handicrafts , house building and shipping, which can be proven everywhere in the island world. However, thanks to the spatial separation, many of the island groups have developed their own cultural ramifications within this cultural area.

These are divided into two main currents: The West Polynesian cultural area with Tonga , Niue , Samoa and the Polynesian exclaves as well as the East Polynesian cultural area, which extends over the Cook Islands , Tahiti , the Tuamotus , Marquesas , Hawaii to Easter Island . The cultures of Western Polynesia were particularly adapted to higher populations. They had a sophisticated legal system and an advanced trading tradition. The social structures were rigid and were cemented by a rigid marriage law.

The East Polynesian cultures, on the other hand, had mainly adapted to the difficult conditions on smaller islands and archipelagos. Although conservative by nature, they had a great deal of flexibility when it came to compensating for the victims of possible natural disasters. The social institutions and hierarchies were in principle more permeable, but their fundamental preservation was enforced with great severity.

The Māori culture in New Zealand plays a special role in this context . This comes from the East Polynesian culture, because the islands were populated by East Polynesians. Confronted with the requirements and peculiarities of life on large islands, the Māori culture has since gone its own way in many areas.

Polynesian societies were decidedly warlike, and frequent campaigns between rival kingdoms were common. These wars were not infrequently fought with extreme cruelty, and in many ethnic groups human sacrifice was part of everyday life in such conflicts.

All Polynesian cultures have in common that they have never developed a written language . All knowledge and the history of each island were passed down in oral tradition by means of often thousands of lines of long chants and texts. The Rongorongo script from Easter Island is an exception, the exact origin of which is still unclear. The Polynesians were also unfamiliar with the processing and use of metals . The first Europeans who came into contact with Polynesians described themselves as “discoverers” and came to the erroneous assessment that they were dealing with a primitive form of culture. It was not recognized until late that the Polynesian culture was highly developed and capable of adapting to its difficult maritime environment.

religion

Traditional Polynesian Religions

In the Polynesian languages there is no independent word for religion, because in the Polynesians' worldview there was no difference between a world on this side and a world on the other. As with all ethnic religions , different ideas are also found in closely related groups. It is all the more astonishing that one can speak of an essentially uniform Polynesian religion (and, moreover, of a homogeneous cultural area ) in the vast Pacific Ocean with its isolated groups of islands, which inevitably led to a great isolation of its inhabitants . This fact was discovered early on by ethnology, but for a long time it concealed the existing differences and led to incorrect theories (such as Wilhelm Schmidt's "primordial monothism thesis" ).

The first colonizers of Polynesia are called Manahune (for example: the experts of Mana) according to tradition . They had an animistic worldview of the (divine) ensouled nature and human life. Demons, ancestral spirits , other spirit beings and protective gods ("Aitu") were a living part of their daily life. The ancestor cult was of great importance, because the human ancestors were considered a real and extremely important authority, whose consent was asked for every important decision. The myths of the cultural heroes "Maui" (the rogue) and "Tiki" (among the Maori "the first man" ), who played an important role in the development of life, fertility and human culture (especially fishing), date from this period ) were involved. Due to the ubiquitous island-sea and earth-sky contrast in the Pacific, such contrasts dominated the oldest mythology of the Polynesian ethnic groups.

The contrast between life and death has also led to a dichotomous conception of man in Polynesia : On the one hand there is the body, which is usually called tino, and the "soul", which during man's lifetime is called agāga (Samoa), iho ( Tahiti), wailua (Hawai'i), wairua (Maori) or kuhane and 'uhane (Marquesas, Hawai'i, Mangareva, Tuamotus, Easter Island).

The Polynesian religion (s) inseparably reflect the socio-political structures of the pre-state chieftainship : While the common people are traced back to the Manahune, the legend places the nobility in the ancestral line of the Ariki : later immigrant families who came from the mythical original home " Hawaiki ”, who often saw themselves as direct descendants of famous creator deities and who had much more“ mana tapu ”. This legitimized their power.

Apart from various differentiations in the individual Polynesian societies, variants of the name Ariki are known almost everywhere. In the Marquesas chiefs are called hakā'iki and in Mangareva tupua and 'akao. Dealing with all these rulers was more or less strong, always or temporarily restricted for the common people. In the case of the sacred ruler of Tonga, the Tu'i Tonga, and the 'Ariki Mau or' Ariki Henua of Easter Island, this went so far that they became incapable of government and a secular ruler, the Tu'i Ha'atakalaua or Tu'i Kanokupolu (Tonga) or the Tagata Manu (ie Vogelmann Easter Island ) was used.

The polytheistic world of gods and the strong stratification of Polynesian society in nobility, common people and slaves began with the Ariki . This had a significant impact in all areas of Polynesian society. Whether the social hierarchy (nobility, common people, slaves) or the daily life of the individual, every detail of Polynesian culture was subject to the conclusions from this worldview: every handicraft, every art, every fishing trip and every armed conflict was directly related to this equally secular as it was spiritual view of reality coupled. An understanding of the Polynesian culture and society without fundamentally incorporating this transcendent attitude is therefore not possible.

(see also: Hawaiian religion and mythology of the Māori )

The Polynesian heaven of gods

Starting from Maui and Tiki, the Polynesians developed a strongly hierarchical world of gods in which each noble family had "its" own god. They were the chief deities in some parts of Polynesia.

Although the fundamental religious ideas in all Polynesian societies were very similar in the manner described above and were based on the same fundamental fundamental ideas - for example the human-shaped gods with fixed places of worship - different forms and beliefs have developed in the various regions. The gods of the Māori are therefore not to be equated with those of the peoples of Tahiti or Hawaiʻi. This is based on the fact that the Polynesian world of gods is very strongly tied to the respective region and genealogy of the local peoples. Although there is a common root of this world of gods for all Polynesian peoples, its further development is dependent on these same regional conditions:

They all have in common the idea of a creation myth that deals with the creation of the world. The first gods appear in the context of this myth. From these different genealogies then develop, which on the one hand have the development of the sexes of the world of gods as their content, but soon also include the history of human sexes in this framework. As I said: the otherworldly and thisworldly world were inseparably interwoven in the eyes of the Polynesians. It could well happen that within the framework of such genealogies the ancestors of a human race are closely related to the god or goddess who chose the local volcano as their home. In many cases, kings or people from noble families were therefore elevated to the status of gods during their lifetime.

Well-known gods of the Polynesian religion are Hina, the moon goddess, or Pele , the Hawaiian goddess of the volcanoes. The middle deities ("Atua") had three main gods: Tane, Tu and Rongo (Hawaii: Kane, Ku and Lono). Tu (or Ku) was the god of war who also claimed human lives. Rongo (Lono) was the god of peace and agriculture, Tane (Kane) the bringer of sunlight and life. Another (male) god was Tangaroa (Tangaloa, Ta'aroa), the ruler of the sea, who was worshiped on some islands of Polynesia as the supreme creator god and ancestor of the noble families. The tradition of the World Egg is related to it : Tangaroa once slipped away from an egg-shaped structure, with the upper edge of the broken egg shell today forming the sky, the lower edge the earth. On the lowest rung of the Polynesian hierarchy of gods are the ancestral spirits and protective deities already known to the Manahune.

The myths, gods and genealogies have been passed down for thousands of years in the songs and texts of the various Polynesian peoples, often in the form of very vivid and drastic representations. The divine heaven of Polynesia was therefore extremely diverse and, thanks to its regional forms, hardly manageable. The myths that arose from him - provided they have not been irrevocably lost in the course of Christianization and colonization - will therefore keep research busy for many years.

Mana

Another central element of Polynesian religious beliefs can be found under the term " mana ": In its fundamental meaning, mana means nothing more than " power ". However, this term is much wider in the Polynesian worldview than it is usual in our culture, since - as indicated above - the Polynesians did not separate the world beyond and this world in a way that we are familiar with. Mana has a strong spiritual component in Polynesian culture and is therefore also and to a significant extent understood as a spiritual power. It denotes a spiritual force that pervades the otherworldly world of gods and ancestors as well as the thisworldly world of daily life. In the eyes of the Polynesians, everything is permeated with this power: every stone, every plant, every animal and every human being has the appropriate mana. However, this applies not only to individual entities, but also to higher-level relationships. A forest has its specific mana just like a fringing reef, a mountain or an entire island. This relationship extends deep into the hereafter, connects every single stone, person or brook with the world of the ancestors and gods and beyond them with the entire creation of this world and the other.

The assumption that such a force existed had very tangible effects on the everyday life of the ancient Polynesians. On the one hand, they were convinced that the flow of Manas was stronger the closer it was to the otherworldly, “divine” realm. Consequently, they assumed that a person whose genealogy could be traced back in a direct line to one or more gods or important ancestors must also be the bearer of a particularly strong mana. Many Polynesian aristocratic families attributed their claim to a special position in Polynesian society to this. But it also worked the other way round: A person who distinguished himself through special deeds proved his spiritual power and thus his closeness to the ancestors and gods. If these deeds were big enough, he might even be the founder of his own genealogy, which is now also reflected in the songs and texts through which the Polynesians transferred their cultural heritage. It often happened that the explorers as well as the first settlers of a hitherto unknown island became the point of reference for such a newly created genealogy and in this way helped new noble families to be born. Their adventures in discovery and settlement as well as their proximity to the special gods of this newly discovered island then became the subject of the original myths of this island society.

This way of thinking is the root of the richness of Polynesian mythology. The basic conception of the nature of the world within this framework remains the same throughout the Polynesian cultural area. However, the special mythology of an island society could lead to clear differences in religious and social practices. Due to the local peculiarities of the various island groups, these often took on different forms, and since religion and daily life could not easily be separated in the context of Polynesian thinking, this also led to pronounced differences in the social structures.

taboo

An important means of shaping social structures in Polynesian society was the different treatment of so-called "taboos":

The term tapu (hallowed; Hawaiian: kapu ) was used in traditional Polynesian society to describe the absolute prohibition of entering certain places, of touching or addressing objects, animals and people who were identified as the seat or bearer of a special type of mana. The pronouncement of certain words or concepts could also be subject to a prohibition in this way. The term taboo, which is also common in European-Western society today, goes back to this Polynesian root. First and foremost, these taboos served to consolidate socio-religious structures. For example, certain places were only allowed to be entered by designated people at set times, who usually belonged to the higher classes. Other places were used for purification and sacrificial rituals. During this time, men who underwent such rites were forbidden by taboo from getting close to or even touching a woman. There were a variety of such rules and failure to comply with them could result in severe penalties. The execution of the death penalty for breaking taboos was not uncommon.

Some of the imposed taboos can also be interpreted functionally from a Western perspective: For example, certain planting areas or fishing grounds were often given a taboo for certain times, which gave them sufficient time to regenerate. Others had population control over the content or consumption and consumption of resources and food. Here, however, there are also many taboos that seem less acceptable from a modern point of view: In many Polynesian societies, for example, women were strictly forbidden from consuming meat and certain valuable fruits.

There were also taboos that forbade members of the community who are lower in the social hierarchy to step over the shadow of a superior or to meet him on an equal footing. There is a mixture of rules here, which in the various Polynesian societies led to the development of sometimes fundamentally different social and economic structures. What they all had in common, however, was the unconditional derivation from mostly metaphysically based causes.

Magic and religious practice

The Polynesians' mixed worldly-spiritual view of reality had a fundamentally pragmatic aspect: They were convinced that they could have a concrete influence on this reality in all its levels. Although they saw themselves to a large extent as victims and playthings of otherworldly powers, they assumed with deep conviction that they could be a factor themselves in this area. To exert magical influence on the course of fate was therefore a natural basic condition of human activity. This was true for the common man as well as for the specialized caste of priests. Whether sowing, building a hut or fishing, it was always a concern of everyone involved to draw the blessings of gods and ancestors on the respective project and to guide the flow of mana into its success.

The practice of the old Polynesian religion was therefore a fundamental part of the normal everyday life of every member of this culture. The constant work of gods and ancestors in shaping daily reality was taken for granted. Mana was seen as an influenceable and malleable force, with the help of which the success of all actions was supported. The common man was allowed a certain freedom in shaping his personal beliefs. He was largely free to choose the god or gods to whom he wished to pay homage. Nobles and members of respected families had this possibility to a lesser extent, as they had to orientate themselves on the specifications of their descent, which were handed down within the families by means of genealogies, often several thousand lines. The connections made by the ancestors to certain gods and events in the otherworldly world were binding for them if they wanted to receive the blessings of the ancestors and to remain carriers of the resulting strong mana.

There were four types of religious offices and vocations on most of the islands:

- Ritual priest. They were close to the chiefs and performed ritual acts such as sacrifices,

- Inspired priests ,

- of spirits possessed ,

- wizard

Religion in Modern Polynesia

Shortly after the British research trips in the 18th century, intensive Christian missionary work began in Polynesia. The main cause was the evangelical revival movement in England and the officers on board the ships were mostly members of the Church of England and advocated the Christianization of the "savages" . In 1795 the London Missionary Society was established and 18 years later the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society , both of which made considerable efforts to Christianize the Polynesian population. They were characterized by the strictness with which they prevented any syncretistic attempts to “link” traditional faith and Christianity. Missionary activities also arose early in the French sphere of influence. Hardly anywhere else was the missionary work in the colonial era as successful as in Polynesia. In spite of everything, there were syncretistic-religious movements on some islands in the 19th century who tried to create “new Polynesian religions” from elements of the traditional and Christian religion. For example the Kaoni movement in Hawaii (from 1868), the Iviatua religion on Easter Island (from 1914) or Pai Mārire in New Zealand (from 1864).

Today most of the residents of the Pacific Islands belong to a Christian church or denomination . Church service, community work and church festivals are part of everyday life. Nevertheless, original elements of belief that are very important for the preservation of cultures have been preserved on many islands. This includes the worship of (mythical) ancestors, the traditions of creators and spirits as well as of powerful cultural heroes. The old gods (or the elements they stand for), the religious myths as well as mana and tapu are still trapped in people's thinking despite Christianization.

The social order of Polynesian society

The structure of Polynesian society is naturally closely related to the beliefs outlined above. Basically, Polynesian societies were subject to a strict hierarchical order, compliance with which was enforced with great severity. This hierarchy followed the aforementioned genealogies and placed the families at the top of the community, whose ancestral lines were deeply rooted in the mythology of the respective people.

The nobility

At the head of every social formation were the families of the nobles. They provided the heads and kings. They drew their claim from their position in the genealogy of the national community. Usually, these ancestral lines can be traced back to the guides and crews of those canoes who were the first to reach and colonize the respective island or group of islands. The degree and importance of the members of a family in all their ramifications depends on the proximity to which they could trace their ancestry to the more important representatives of this ancestral line. Having a precise knowledge of these lineages was (and still is) of the utmost importance for a Polynesian.

Normally the line of inheritance was passed on through the firstborn sons, but it could also happen that she followed the maternal line if this was advantageous in terms of social and ritual classification. It was also a common practice to bring promising young people closer to their original lineage through adoptions . As previously described, a man could also increase his social status by performing great deeds, be it as a warrior, sailor, or in some other area. In this way, a system of social order, which was essentially rigid and tied to tradition and ancestral cult, was given the necessary flexibility to adapt to the adverse living conditions of a difficult and dangerous oceanic environment, which all too often affect the existence of a people as a result of storms, Famine and armed conflict threatened.

The type and degree of sovereign powers vary in the individual Polynesian societies, but in principle it was the nobility who made the final decisions about war and peace and organized the work on all communal tasks. The strongest social differentiation and a partly sacralized chief power applied to Tonga , Tahiti and Hawaii . No single person or family owned land on any of the islands. Nevertheless, it was the duty and privilege of the nobility to decide how the land was used, how food was grown, and how other resources and skills of society were used. The chief complained to the members subordinate to him for a share of the harvested food, the fishing, the results of handicrafts or priestly services, in order to then distribute these according to his ideas to other members of society. A part of this he passed on to his superior leader or king, the rest he distributed to his subjects in order to reward them for general-benefit work or simply to achieve a fair compensation in the provision of all members of his national community. All of this happened within the framework of its religious and ritual significance as a bearer of strong manas and mediator to the gods and otherworldly powers.

Fundamental decisions about the cultivation of certain foods or the construction of houses, temples or canoes were made on the basis of both secular and religious principles and necessities. The role of the Polynesian nobility was split: on the one hand, they largely determined the course of Polynesian bartering and social life, and on the other, they placed it in strict relation to religious requirements.

The experts

Experts (called "kāhuna" ( singular : "kahuna") in Hawai'i and "Tohunga" among the Māori) played an important role in all Polynesian societies . They stood by the aristocrats as advisors and formed the elite of Polynesian culture in all questions of religious, medical, technological and artistic nature: Whether priests, navigators, wood carvers, boat builders, healers or house builders, there were specialists for all areas of Polynesian knowledge were well instructed in the art of their respective subject.

However, the Polynesians did not have a general school system for training these experts. The knowledge of their respective profession was passed on by word of mouth, similar to that of the nobles within the framework of family traditions. Here, too, genealogies played an essential role, but experts made use of the possibilities of adoption much more frequently to give young talents an opportunity to develop. The various social classes and professions in Polynesian society were usually identified by the type of their tattoos , which were also carried out by experts .

Although a "Stone Age culture", Polynesian society was highly specialized and highly productive in a variety of skills. The natural resources available on many islands were often very limited, but the Polynesian experts knew how to make optimal use of what was available. However, all of these areas were always and unconditionally included in the religious context. A craft or an art without a religious and magical background was unthinkable to the Polynesians. For this reason the priests played a special role in the ranks of the experts: no action, whether it was the sowing of a taro field, the building of a house in a certain place, or a sea voyage, was carried out without questioning and the blessing of a priest carried out.

All medical treatment was as much a magical as a worldly operation. The role of the priests was not limited to the direction of ritual ceremonies, but consisted to a large extent in supporting the respective endeavor with magical means.

The social weight of the priests was essentially reflected in the importance of the temple or ceremonial place assigned to them in the eyes of the Polynesians. There were also different specializations within the priestly caste. While some were more concerned about healing, there were others who were concerned with martial affairs and interpersonal conflicts. In the beginning of the 20th century, priests were found in Hawai'i who specialized in conjuring evil curses down on their fellow men.

The common people

At the bottom of the Polynesian social hierarchy was the ordinary member of society. His rights and duties were different in the different Polynesian cultures. While the people were naturally allowed to claim inalienable rights on some archipelagos, their will was very little in the Hawaiian society, for example. There the command of the nobility was an iron law and violations were severely punished. The common people, often under the guidance of experts, did the simple work, tilled the fields, built houses and temples, or formed the crew of the canoes for fishing. Nevertheless it was a proud people, because all men from this class were at the same time the warriors of the national community.

In some Polynesian societies there was another group below the level of simple members of society whose rights did not significantly exceed those of slaves. Usually these were the descendants of formerly conquered and subjugated tribes whose genealogy had lost all value as a result of this defeat.

The role of women

Polynesian society was clearly male dominated and strictly patriarchal. Women were only given a subordinate role. Many Polynesian tribes were forbidden from eating certain foods that men alone were entitled to consume. Likewise, they were often forbidden to go to holy places with a corresponding taboo, to be present at the men's meals or to go on board of boats. Violations of such taboos were usually punished with death in women, while men were often allowed in such cases to wash themselves clean of the guilt committed by means of special rituals.

Within the framework assigned to them, however, women were highly respected in Polynesian society and performed important work in many areas: They mastered a number of handicrafts, such as the production, dyeing and decorating of clothing or of wickerwork, jewelry and household items. In addition, they had a variety of tasks to do in the household, tilling the fields and gathering food on the reefs.

Usually they lived in the state of marriage, whereby the men were allowed, depending on their social position, to marry several women. Even before marriage, it was common in Polynesian society for both young men and women to enter into a variety of sexual relationships with changing partners. As a rule, illegitimate children were also well suffered. A woman or a man without such experience was considered unattractive.

Types of settlement

The way in which Polynesian ethnic communities colonize various islands and archipelagos is, on the one hand, adapted to the respective local conditions and needs and, on the other hand, it is a consequence of the cultural tradition of the specific society. On small atolls, for example, one often finds the shape of the village that is located on one of the islands, while the remaining islands are left uninhabited as an agricultural kitchen garden and are only visited for the purpose of foraging and growing useful plants. In a village like this, all the houses are nestled so close together on one or more central paths that their roofs touch each other. These villages offered their residents the greatest possible security and security appropriate to the circumstances.

But there were also atolls covered by small hamlets consisting of four to five houses. Here, individual families lived and managed a small islet and settled on the spot. But even on atolls populated in this way there were usually one or two larger villages in which temples, ceremonial grounds and the large boat huts were concentrated. As a rule, these were archipelagos that were not so easily exposed to enemy attacks due to their location. This form of settlement by means of small hamlets is also often found on smaller islands of volcanic origin, whose narrow gorges and valleys, at least inland, did not allow the construction of larger villages.

On the other hand, on large islands - especially if these were populated by rival kingdoms - there are often large village communities equipped with fortifications. The largest and most well-fortified village complexes of this type were maintained in New Zealand by the Māori living there. In many places they built villages, the Pā , lushly protected with palisade walls on the crests of hills , in the center of which there was a mighty fort, which in the event of an attack offered the residents of the village an additional shelter.

food

In the course of the colonization of the individual island groups by the Polynesians, they introduced various crops into the newly won territories. In this way, for example, plants such as taro , breadfruit , sweet potatoes , bananas and sugar came to Hawaii for the first time. So far, a total of 72 plant species have been identified that were introduced into the Polynesian settlement area by humans. 41 to 45 of them reached the Cook Islands, the Society Islands and Hiva. At least 29 of them can also be found in Hawaii. The import of these economic crops was of vital importance for the settlers, especially on small islands and atolls, because these usually did not provide the newcomers with an adequate food source.

Although the Polynesians kept farm animals - in particular chickens, in some areas of western Polynesia also pigs - this was only possible to a very limited extent, as they competed with humans for basic food and therefore rarely kept on islands with limited resources could become. During the Lapita culture period, the Pacific rat became a native of many Polynesian islands, as shown by large amounts of rat bones in old garbage pits. This may have been done on purpose, for example as an additional source of food for humans or animals. One consequence was that many smaller animal species disappeared as a result of the rats.

In the course of history, the Polynesian settlers also fell victim to countless animal species, including flightless birds, but also various large reptiles such as the New Caledonian terrestrial crocodile Mekosuchus inexpectatus . However, the basis for the production of animal protein was the sea. The Polynesians were masters of fishing and knew every possible way of wresting its treasures from the ocean. They were excellent divers who looked for mussels in the lagoons, knew about the hiding places of lobsters in the reefs as well as fishing grounds hundreds of kilometers away. The ocean was and usually remained the basis of their existence.

seafaring

Although they had neither a compass nor a sextant , the Polynesians were excellent seafarers who could cover even the greatest distances in the Pacific Ocean with confidence. This ability was of paramount importance in a culture that knew how to colonize this widely ramified island world. The boat builders and navigators were correspondingly highly regarded in Polynesian society. The survival of the community depended on their skills. Each island had large boathouses in which the canoes were made and housed. The exploits of the navigators were sung in songs and dances.

Boat building

Depending on the intended use, the Polynesians used outrigger canoes or double hull canoes of different sizes and designs. For coastal traffic and fishing, they were usually limited to the smaller outrigger canoes. For long-distance journeys and the transport of warriors, they resorted to the much larger ocean-going double-hulled boats , the forerunners of today's catamarans . The basic design of these boats can be found in the entire Polynesian settlement area as well as in large parts of Micronesia and Melanesia . Regional differences are mainly evident in the design and decoration of individual components such as B. the bow and stern of the canoes.

The hulls of the canoes had a bow and a stern of the same shape. They could move in both directions without having to turn. This was a great advantage when landing and casting off on flat sandy beaches. Both outrigger canoes and double-hulled boats had a platform between the hull and the outrigger or the two hulls on which the crew stayed. Both could be propelled by paddles as well as provided with sails.

Fixings for the masts were on the platform between the hulls or between the hull and the boom. In the case of cruising through the wind, the crew could take the sail and mast and attach it to the other end of the ship. In this way it was achieved that the crew and boom were always on the windward side of the boat.

The double-hulled boats in particular can also be assessed as suitable for the oceans by today's standards. Compared to modern catamarans, however, they were built quite narrow. This is due to the physical limits of the building materials used: high shear forces act on boats with two hulls. The wood of the platforms, which are fixed with coconut fiber and which connect the two hulls, therefore had to be designed to be very compact. The sailing characteristics of the canoes were good, but not uncritical.

The Polynesian sail, which resembles a triangle pointing downwards, allows cruising against the wind. However, with this sail cut, the pressure point of the wind is relatively high, which affects the lateral stability of the boats. The way in which the twin-hulled boats were steered was also unusual: instead of using a tiller handle, you steered with the help of paddles on both sides of the hulls, by dipping a paddle to slow the speed of the respective hull and thus forcing a change of direction.

Large double-hulled boats reached a length of twenty to thirty meters. They could carry up to two hundred people (war canoes). In the case of a long-distance journey to colonize a newly discovered island, they were occupied by twenty to twenty-five settlers who carried travel supplies, tools, seeds, plants, and farm animals with them. Such trips were usually carried out in larger groups. Foreign islands were usually discovered by fishermen who had ventured far out into the high seas in search of new fishing grounds or in pursuit of schools of fish.

The materials and construction methods used were based on the resources available on the respective home island. Islands of volcanic origin often had a population of larger tree species. In this case, the builders of the canoes like to use a hollowed-out tree trunk for the base of the hulls, the freeboard of which they raised with attached planks. These were neatly grouted and fixed with coconut fiber.

On islands without a stock of suitable trees and for building very large canoes, planks were used from the outset. All the woods used on the hull and platform were tied together with strings made from the fibers of the coconut's outer shell , and the joints in the planks were sealed with tree resins . In areas where coconut palms did not grow, fibers from other plants were used.

The art of canoe-making has been passed on from generation to generation in boat builders' families. Orally transmitted chants and texts, in which the required knowledge was integrated, played a major role here.

Accurate navigation in an extensive sea area such as the Pacific Ocean with its thousands of small and tiny islands is one of the most difficult nautical tasks of all, all the more the performance of the Polynesian navigators , who had mastered this challenge well over a thousand years ago without being more nautical Use aids such as compass or sextant . Large parts of this cultural treasure were irretrievably lost with the loss of the underlying chants and lyrics.

The course determination of the Polynesian navigators was based on the exact observation of both astronomical and terrestrial components. During a sea voyage, they had to put these together and keep them in mind in order to be able to derive a valid location and course from them. For this purpose, courses to known destinations were divided into sectors, each of which was assigned certain astronomical or terrestrial properties. If the journey took you to an unknown location, the route leading there was memorized sector by sector to enable a return.

The constant observation of the movement of the sun , moon , planets and stars was of central importance. The Polynesians knew almost 300 stars and constellations and knew how to assign them to the various course sectors. The memory required for this was enormous, because no maps existed for any of these dates in the Polynesian culture , only orally transmitted chants and texts.

The same applies to the observation and assessment of the sea, the airspace and the weather . They knew the locations of innumerable fishing grounds , shoals and currents and were able to draw their conclusions from the swell underlying a swell . They were also able to gain information for their location and course determination from observing the flight of seabirds , the type and quality of floating debris , the formation of clouds or the behavior of fish and dolphins .

The Polynesian navigator had to internalize all of this from childhood, because the art of bringing together such complex information is not a precise science, but rather requires the development of a deeply rooted feeling for the sea. Here too - as in all areas of knowledge transfer in Polynesian culture - the art of navigation has been passed on from generation to generation within families . The budding navigator was taken with him on trips, gradually learned to interpret the associated chants and texts and, with increasing skills, was more and more involved in responsibility. The staff map technology was available to him for exercise purposes and for preparation on land . With the help of these self-made memory aids, he was able to memorize and practice the various sectors. However, he was not allowed to carry such a staff card at sea.

In 1976 a unique attempt was made to revive the old Polynesian seafaring tradition. This year the Hokule'a (= star of happiness ) set sail and covered the 4000 kilometer stretch from Hawaii to Tahiti without any help from sea charts or nautical instruments. The Hokule'a is a faithful replica of an old Hawaiian double-hulled boat and the navigation methods used on it were, as far as possible, based on the traditional approaches of the old Polynesian navigators. This trip provided scientific proof for the first time that such a type of navigation is actually possible in principle over long distances. The old legends of the navigators who were able to “read the sea” have since gained new weight. Such achievements are attributed, for example, to the legendary figure Ui-te-Rangiora .

Medicine / naturopathy

The skills of the Polynesian culture in medicine and naturopathy were well developed in some areas. They had a basic knowledge of obstetrics and the treatment of childhood diseases, were able to treat both broken bones and accidental injuries, and were familiar with the effects of a large number of medicinal herbs that grew on their islands. Polynesian medicine was practiced by trained specialists. These were usually limited to sub-areas of medicine, the knowledge and procedures of which were passed on from generation to generation in the family tradition.

In Polynesian society there was therefore not a “ medicine man ” who was responsible for every type of illness, but a decision was made on a case-by-case basis as to which specialist to turn to. Spiritual and worldly aspects stood side by side and complemented each other. A traditional Polynesian healer used magical as well as secular practices and methods to alleviate illness or injury. Usually, these healing treatments therefore took place in the context of a religious-ritual ceremony in the circle of family members and members of the national community to which the patient belonged. Often they were accompanied by religious dances and chants by the community members present.

Nowadays attempts are being made to revive such methods, for example by breathing new life into traditional Hawai'i massage techniques . However , Polynesian medicine was unable to counter the effects of the infectious diseases introduced by European visitors and immigrants from the middle of the 18th century .

art

Much evidence of Polynesian art was irretrievably destroyed in the encounter with the European "discoverers" and soon afterwards conquerors. This is particularly evident in the field of architecture and sculpture. Here it was above all Christian missionaries who were particularly concerned about tearing down the old “pagan” temples, who were responsible for the systematic destruction of Polynesian works of art. Almost everything in Polynesian art had a religious reference and therefore fell victim to this religiously based “iconoclasm”.

music and dance

This also applied to music and dance. On many Polynesian islands, the performance of traditional dances and songs was forbidden in times of proselytizing and colonization. As in the music of Tuvalu , many of the ancient texts and songs that were passed on exclusively by oral tradition have been lost elsewhere. Throughout Polynesia, dance and music played an important role in daily life, as part of rituals or religious celebrations, and in the support of oral traditions.

Due to the large extent of the "Polynesian triangle" (Hawai'i, Easter Island, New Zealand), a large number of related traditions had developed. B. the dances of Tahiti, Hawai'i ( Hula ), and Samoa belonged. In some old Polynesian societies, dancers were highly respected specialists who made a living from the practice of their art. Nowadays many places in Polynesia are trying to revive these ancient traditions. In Hawaii, the traditional hula dance has again attracted a large number of people, and the same applies to French Polynesia or New Zealand and the local dances there.

The importance of music and dance for Polynesian culture can be guessed at when one looks at how the inhabitants of Takuu , a small Polynesian exclave, still think about it today. For some time now they have been trying to live according to old traditions and traditions: twenty to thirty hours a week they devote themselves exclusively to dance and music.

Jewelry and textiles

Inseparable from dance and rituals are the beautiful wreaths (rei, lei ), which are made into true works of art from flowers, herbs and shells. Wickerwork (e.g. mats, fans, baskets) from the leaves (Hawaiʻi: lauhala ) of the hala tree ( Pandanus , in Hawaiʻi: hala ) or other vegetable materials were often made with great skill, even for daily use. The Polynesians were also masters in multi-colored textile printing ( Tapa , Kapa) and today they are returning to this old art.

Carving and sculpture

The Polynesians were excellent wood carvers and sculptors. Both the residents' houses and the boats and canoes were richly decorated. The majority of the motifs used here had a religious reference. In front of the temples there were numerous columns and statues made of wood and stone, some of them several meters high. In this regard, the monumental stone figures on Easter Island , which still convey a vivid impression of the artistic achievement of the Polynesians, have become famous .

Oral transmission

Since the Polynesians had never developed a written language, apart from the Rongorongo woods on Easter Island, oral texts and chants play a prominent role in this culture.

However, passing on the collective knowledge of a culture orally is a difficult undertaking. Every member of this society therefore had to learn a large number of texts in order to receive knowledge of the culture. In order to make this task easier and more beautiful for people, all these texts were related to songs and dances. From an early age, the Polynesians were involved in the performance of these dances and songs.

The structure of the Polynesian languages also made it easier to pass on profound knowledge in this way. All Polynesian languages have in common that texts written in them can be interpreted in a variety of ways, since both words and grammar make it possible to give the same text different levels of meaning. For example, the text of a song about the discovery of an island can be understood as a dramatic travel description and heroic epic, at the same time providing a navigator with precise information about the travel route covered and at the same time used for the religious and genealogical classification of a family clan.

under Polynesian languages

Sports

The Polynesians did not know any sports in the European sense. But they often fought in wrestling matches or conducted mock fights with their weapons. The sport of paddling was also a cultural event in Polynesian society, as there were times reserved for festivals and competitions when acts of war had to rest. Then the men of different tribes measured their strength in races in their canoes. During these festivals, the men of the various clans and followers were able to prove their skills in mock fights and compete in wrestling matches. The surfing was mainly in Hawai'i become a popular sport.

regional customs

Table of Polynesian Islands

The following islands and archipelagos are part of Polynesia Independent states  Cook Islands

Cook Islands

in association with New Zealand  New Zealand

New Zealand

independently  Niue

Niue

in association with New Zealand  Samoa

Samoa

independently  Tonga

Tonga

independently  Tuvalu

Tuvalu

independent (Ellice Islands) Subdivisions of Independent States or Dependent Territories  American Samoa

American Samoa

Overseas territory of the USA  French Polynesia

French Polynesia

Overseas (POM = Pays d'outre-mer) of France ( Society Islands , Tuamotu Archipelago , Marquesas Islands , Gambier Islands , Austral Islands )

Hawaii Islands

Hawaii Islands

State of the USA  Phoenix Islands

Phoenix Islands

Kiribati archipelago  Easter island

Easter island

Province of Chile  Line Islands

Line Islands

Kiribati archipelago  Pitcairn Islands

Pitcairn Islands

British overseas territory  Tokelau

Tokelau

Overseas Territory of New Zealand  Wallis and Futuna

Wallis and Futuna

Overseas territory of France Uninhabited Territories in the Polynesian Triangle

(with no known Polynesian tradition) Baker Island

Baker Island

Overseas territory of the USA  Howland Island

Howland Island

Overseas territory of the USA  Jarvis Island

Jarvis Island

Overseas territory of the USA  Johnston

Johnston

Overseas territory of the USA  King attack

King attack

Overseas territory of the USA  Midway

Midway

Overseas territory of the USA  Palmyra

Palmyra

incorporated overseas territory of the USA Exclaves outside the Polynesian triangle  Anuta

Anuta

Part of the Solomon Islands  Emae

Emae

Part of Vanuatu  Futuna

Futuna

Part of Vanuatu  Kapingamarangi

Kapingamarangi

Part of the Federated States of Micronesia  Mele

MelePart of Vanuatu  Nuguria Islands

Nuguria Islands

Part of Papua New Guinea  Nukumanu Islands

Nukumanu Islands

Part of Papua New Guinea  Nukuoro

Nukuoro

Part of the Federated States of Micronesia  Ontong Java

Ontong Java

Part of the Solomon Islands  Ouvéa

Ouvéa

Part of New Caledonia  Pileni

Pileni

Part of the Solomon Islands  Rennell

Rennell

Part of the Solomon Islands  Rotuma Islands

Rotuma Islands

Special Territory of Fiji  Sikaiana

Sikaiana

Part of the Solomon Islands  Takuu

Takuu

Part of Papua New Guinea  Tikopia

Tikopia

Part of the Solomon Islands

See also

literature

- Roland Burrage Dixon: Oceanic. (= The Mythology of all races. Volume 9). Archaeological Institute of America, Boston 1916. (Cooper Square Publishers, New York 1964, OCLC 715319128. )

- Martha Warren Beckwith : Hawaiian mythology. With a new introduction by Katharine Luomala . Yale university press, New Haven 1940. (University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1970, ISBN 0-87022-062-4 )

- Adelbert von Chamisso: Journey around the world. Structure, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-7466-6093-9 .

- Kerry R. Howe: The Quest for Origins. Who first discovered and settled the Pacific islands? University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 2003, ISBN 0-8248-2750-3 . (Penguin Books, Auckland 2003, ISBN 0-14-301857-4 )

- Patrick Vinton Kirch: The Evolution of the Polynesian Chiefdoms . (= New studies in archeology ). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1990, ISBN 0-521-27316-1 .

- Antony Hooper, Judith Huntsman (Eds.): Transformations of Polynesian Culture. (= Memoirs of the Polynesian Society. Volume 45). The Polynesian Society, Auckland 1985, ISBN 0-317-39232-8 .

- Gundolf Krüger: Earliest cultural documents from Polynesia: The Göttingen Cook / Forster Collection. In: Gundolf Krüger, Ulrich Menter, Jutta Steffen-Schrade (eds.): TABU ?! Hidden Powers - Secret Knowledge. Imhof Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-86568-864-4 , pp. 128–131 and numerous illustrations from the museum's holdings.

- Sources for the section "Influence on nature"

- JM Diamond : The present, past and future of human-caused extinctions. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. Vol. 325, No. 1228, Evolution and Extinction. (November 6, 1989), pp. 469-477.

- David A. Burney, Guy S. Robinson, Lida Pigott Burney: Sporomiella and the late Holocene extinctions in Madagascar. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . Vol. 100, 2003, pp. 10800-10805.

- RN Holdaway : New Zealand's Pre-Human Avifauna and Its Vulnerability. In: New Zealand Journal of Ecology. Vol. 12, 1989, Supplement Moas, mammals and climate in the ecological history of New Zealand. Pp. 11–25. ( PDF full text ).

- Patrick V. Kirch: Late Holocene human-induced modifications to a central Polynesian island ecosystem. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . Vol. 93, May 1996, pp. 5296-5300.

Web links

- Literature from and about Polynesia in the catalog of the German National Library

- Database of indexed literature on the social, political and economic situation in Polynesia

- Polynesian Navigation (Academic Study, English; PDF; 3.51 MiB)

- The journey of the Hokule'a (description; PDF; 260 KiB)

- Various books on Polynesian mythology (full text, English)

- Banks Papers on the Cook Expedition (full text, English)

- Cooks Journal (full text, English)

- Cook + Banks + official report (full text, English)

- Te Rangi Hiroa (Sir Peter Buck): Vikings of the Sunrise , Whitcombe and Tombs, 1964 (full text, English, digitized version, New Zealand Electronic Text Archive)

- Lots of general information about Polynesian peoples (article, English)

- Louis Choris' "Voyage pittoresque autour du monde"; Text excerpts regarding the Rurik's visit to Hawaii in 1816 (excerpt from book, French)

- Diversitivität of Polynesian islands (English)

- Classification of Polynesian Island Shapes (1985, English)

- Ethnological films by Karl Rudolf Wernhart (1973) from the collection of the Federal Institute for Scientific Film (ÖWF) in the online archive of the Austrian Media Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Annette Bierbach, Horst Cain: Polynesien. In: Horst Balz et al. (Ed.): Theologische Realenzyklopädie . Volume 27: Politics / Political Science - Journalism / Press. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1997, ISBN 3-11-019098-2 .

- ^ Atholl John Anderson Research Group , Australian National University Canberra : The Rise and Fall of Rapa. In: Adventure archeology. Cultures, people, monuments. Spectrum of Science , September 18, 2006, p. 8. ISSN 1612-9954 (readable here: Spektrum.de , or here in English and in more detail: Prehistoric Human Impacts on Rapa, French Polynesia )

- ↑ Erik Thorsby: The Polynesian gene pool: An early contribution by Amerindians to Easter Island In: Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B Vol. 367 BC 2012, pp. 812-819.

- ↑ Alexander G. Ioannidis, Javier Blanco-Portillo, Karla Sandoval, Erika Hagelberg, Juan Francisco Miquel-Poblete: Native American gene flow into Polynesia predating Easter Island settlement . In: Nature . July 8, 2020, ISSN 1476-4687 , p. 1-6 , doi : 10.1038 / s41586-020-2487-2 ( nature.com [accessed July 13, 2020]).

- ↑ Adventure archeology . Spectrum, Heidelberg 2007,3, 8th ISSN 1612-9954

- ↑ nytimes.com

- ↑ Lapita-Voyage - The first expedition on the Polynesian migration path ( Memento of December 16, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e f Corinna Erckenbrecht: Traditional religions of Oceania . Introduction to the religions of Oceania, in the '' Harenberg Lexicon of Religions '', pp. 938–951. Harenberg-Verlagsgruppe, Dortmund 2002, accessed on October 14, 2015.

- ↑ SA Tokarev : Religion in the History of Nations. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1968, p. 114.

- ^ Hermann Mückler: Mission in Oceania. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-447-10268-1 , pp. 44-46.

- ↑ Mihály Hoppál : The Book of Shamans. Europe and Asia. Econ Ullstein List, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-550-07557-X , pp. 103, 109 f.

- ↑ See article Ancient Hawaiʻi (English)