Rurik expedition

The Russian Rurik Expedition (outdated Rurick Expedition ) was a circumnavigation of the world that took place from July 30, 1815 to August 3, 1818 under the command of Otto von Kotzebue and was intended to be used to discover and explore the Northwest Passage . The expedition of the warship Rurik ( Russian Рюрик) was equipped and financed by the Russian Count Nikolai Petrovich Rumjanzew (Russian Никола́й Румянцев). She found with benevolent support of Czar Alexander I held. However, due to adverse weather conditions, she did not reach her destination and returned earlier than planned. The historical significance of the expedition lies in the numerous new discoveries along the entire route as well as the human and cultural experiences that the crew brought with them from this three-year journey.

Expedition destination

The Russian desire to find the Northwest Passage was primarily for economic reasons. The supply of the trade bases on the east coast of Russia and in the colony of Russian America , which stretched on the American west coast from Alaska to San Francisco , was difficult to maintain by land across the Asian continent and cost a lot of money. The search for a sea route in the north of the European and Asian continents ( Northeast Passage ) had not yet brought the desired success. The sea routes around the southern tip of Africa ( Cape of Good Hope ) or America ( Cape Horn ), on the other hand, proved to be time-consuming and not without risk due to a variety of threats, including adverse weather and piracy . Therefore, Russia hoped to discover a passage in the north of the American continent, which would have been much shorter and possibly easier to drive.

Since all attempts to discover this sea route from the east had failed so far, this time the passage was to be found from the west and explored and passed through in the opposite direction. It was promised that the starting position of the expedition could be improved by the fact that Russia had numerous trade bases on the west coast of the North American continent, which could serve as contact points for supplying the crew and other logistical support for the campaign.

The trip envisaged two summer campaigns (1816 and 1817): The first was to explore suitable anchorages north of the Bering Strait . With the second one hoped to be able to advance further north and east from there the following summer.

The expedition, like many before and after it, did not achieve its goal. However, Otto von Kotzebue was able to prove a coherent ocean current, which was the first scientific evidence for the existence of the Northwest Passage. In addition, von Kotzebue mapped over 400 islands in Polynesia and large parts of the west coast of Alaska. The naturalists documented a large number of unknown animal and plant species.

Expedition participant

In addition to the three subordinates Khramtschenko, Petrow and Koniew, two NCOs, a cook and 20 sailors, the following people took part in the expedition:

- Otto Evstafjewitsch von Kotzebue (1787–1846), lieutenant in the Imperial Russian Navy, captain of the Rurik and leader of the expedition.

- Johann Friedrich Eschscholtz (1793–1831), ship's doctor and naturalist

- Adelbert von Chamisso (1781–1838), naturalist (titular scholar)

- Ludwig Choris (1795–1828), draftsman (was also available to naturalists for documentation)

- Morten Wormskjold (1783–1845), volunteer naturalist (disembarked in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky)

- Gleb Simonowitsch Schischmarew, first lieutenant

- Ivan Yakovlevich Sacharin, Second Lieutenant

During the voyage, the following people went on board at times:

- August 17, 1815: Pilot for the canal and Plymouth.

- October 1, 1816: Two Russian sailors and a passenger: Elliot de Castro, personal physician to the King of Hawaii (from San Francisco to Hawaii)

- February 23, 1817: The South Sea islander Kadu (during the entire summer campaign of 1817)

- May 27, 1817: Two interpreters for the dialects of the northern coastal peoples.

- August 1817: Four Aleutians to strengthen the crew

The ship

The Rurik , named after the Warsaw prince and founder of Russia Rurik (approx. 830 to approx. 879), was a small brig of 180 tons. For the course of the expedition, she was allowed to fly the Imperial Russian flag of war. She was therefore considered a warship . Since the primary goal of the voyage was the discovery of the Northwest Passage, it was only secondarily equipped as a research ship . The accompanying researchers therefore had to submit to the military customs on board. Significant for this are the words of Kotzebues to Adelbert von Chamisso, "that [he] as a passenger on board a warship, where one is not used to having one, has no claims to make." The researchers had little room for plants - and artifact collections available. Much of the collections were immediately stowed in sealed boxes below deck. As Adelbert von Chamisso describes, open collections were often thrown overboard (also at the command of the captain) because they hindered the sailors in their everyday tasks on board.

The ship was only lightly armed, the eight cannons were used almost exclusively for firing gun salutes while entering and leaving foreign ports. Towards the end of the voyage, the Rurik met supposed pirate ships near the Sunda Strait , which were kept at a distance with the help of warning shots.

Before the second summer campaign in 1817, the Rurik off Kamchatka got caught in a storm and was badly damaged. The hastily carried out repair work in Unalaska represented more damage limitation than complete restoration. The condition of the Rurik was officially one of the reasons why von Kotzebue did not want to go further north and gave up the expedition's goal. During the return voyage, the Rurik was overhauled in the Cavite shipyard in the Philippines.

Expedition course

From St. Petersburg to Kamchatka

The Rurik was supposed to reach the Pacific via Cape Horn . This first major stage of the journey, starting from Saint Petersburg and Kronstadt , was already characterized by a number of shore excursions from which the naturalists of the expedition in particular benefited. After an initial short stay in Copenhagen , we went on to Plymouth on the south coast of England to prepare for the long Atlantic crossing. A stay of several days on Tenerife in the Canary Islands enabled the naturalists to explore a world that was new to them. The Rurik finally reached the island of Ilha de Santa Catarina off Brazil on December 12, 1815 and docks at Florianópolis .

The further course of the journey to the Russian peninsula Kamchatka - around Cape Horn - was mainly characterized by a long stay in Talcahuano , Chile , during which extravagant festivities were celebrated with the governor, the commander and the nobles of the city and the surrounding area. The subsequent voyage across the Pacific was made in a hurry to get to Avacha Bay early enough to prepare for the 1816 summer campaign. It was necessary to use the few warm days of the year to be able to penetrate far enough north before the winter icing set in again.

For the route to Awatscha, Otto von Kotzebue chose a route that is far from the usual trade routes. In doing so, he mapped numerous islands of the Polynesian archipelago, which had not yet been explored. The names given to those islands at that time, however, have changed frequently to the present day due to later colonization by various other nations. On June 19, 1816, the Rurik docked in the Avacha Bay off Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky .

Summer campaign 1816

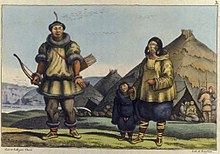

The summer campaign of 1816 began on July 14th with the departure from the Bay of Avacha on the Kamchatka Peninsula and ended with the entry into the port of Unalaska , an island of the Aleutian Islands , on September 7th. It was used to explore the sea and coasts north of the Bering Strait and to find suitable anchorages in preparation for another advance during the summer campaign of 1817. During this trip, the Kotzebuesund with the Eschscholtz Bay and the Chamisso Island and other landmarks were discovered (see map on the right). In addition, contact with the local people living there was established and maintained. After the first cautious approach, it was often possible to trade: for needles, scissors, knives and, above all, tobacco, the expedition participants were able to exchange provisions, clothing and handicraft cultural products in the form of objects of daily use, works of art or cult objects.

The Rurik continued to sail from Avacha Bay on a north-east course until it encountered St. Lawrence Island and then crossed the Bering Strait along the Alaskan coast. Here the captain first followed a sandbank-like chain of islands, which lay directly in front of the coast, until the Schischmarew Bay was reached. After a short exploration of the bay, the journey was continued to Cape Espenberg in the north, at the entrance to Kotzebuesund. Hoping to have found access to the Northwest Passage there, the course changed to the east on August 2nd. However, the Rurik soon met the Baldwin Peninsula and followed the coastline to the south until the entrance to Eschscholtz Bay opened, into which the ship sailed between the Baldwin Peninsula and Chamisso Island. In the days that followed, the captain had the bay explored by rowing boats, but had to realize that there was no further progress. On August 7, Eschscholtz discovered icebergs in the south of the bay.

On August 11, the expedition resumed the journey and followed the southern coast of the Kotzebuesund to the mouth of the Kiwalik River. There von Kotzebue asked an Eskimo about the further course of the river. He suspected a direct connection to southern Nortonsund across the Seward Peninsula. Because this assumption could not be confirmed, the expedition was resumed in a northerly direction until it reached Cape Krusenstern in the north of the entrance to the sound. Because of the meanwhile advanced summer, the captain decided to cross the Chukchi Sea in a westerly direction and along the Russian coast to pass the Bering Strait to the south.

South of the strait, the Rurik sailed into the St. Lawrence Bay (Russian zaliv Lavrentija ) and anchored there. The captain exchanged fresh reindeer meat with the Chukchi who lived there. During the stay, numerous Chukchi from the southern Metschigmensk Bay (Russian: Mečigmeskij zaliv ) came to St. Lawrence Bay to marvel at the newcomers. Due to bad weather, the captain did not set course for the eastern tip of St. Lawrence Island until August 29. Due to the persistent thick fog, the Rurik ran at a respectful distance along the island to the east, did not dare to anchor and finally set course to the south. On September 3, the island of Saint Paul in the Pribilof Islands came into view. Here, too, the Rurik continued to sail and entered the port of Unalaska on September 7th.

In Unalaska, the agent of the "Russian-American Company" (a Russian trading company) was tasked with preparing the summer campaign for next year, while the Rurik was supposed to spend the winter in southern latitudes. In addition, 16 Alëuts (including a translator) should be ready to go north the following year.

From Unalaska through the Eastern Pacific

In order to avoid the harsh winter in the north and to allow the team some rest before the planned summer campaign of 1817, the Rurik moved south to warmer regions. This trip took them from Unalaska to San Francisco in California, Spain, and on to Hawaii and the Marshall Islands .

In San Francisco and Hawaii, the crew had to take on diplomatic tasks that went far beyond the scope of their scientific mission. First of all, in negotiations between the Spanish governor of the region Don Paolo Vicente de Sola and the Russian Empire - represented by Otto von Kotzebue in his function as lieutenant in the Imperial Russian Navy - a dispute was provisionally settled in the Presidio of San Francisco, which the proceedings of the Russian-American trading company on the Californian coast concerned: There had been disputes under international law with Russian colonists who, without the permission of the Spaniards, had built a fur-trading settlement and a fort a little further north on Bodega Bay. Von Kotzebue succeeded in postponing a possible armed conflict by persuading both parties to make further action dependent on the attitude of their respective governments. However, there was no official reaction from the governments concerned and so the status quo remained for some time.

Hawaii, too, had recently fallen victim to a political confrontation with forces of the Russian-American trade company. Two of their merchant ships had hoisted the Russian flag on one of the islands and tried to take possession of it for the tsar. A bloodshed could be averted in time thanks to the mediation of some Europeans and Americans living there, but in response to their expulsion the Russian seafarers threatened to invade the islands with war. In this situation the Rurik reached Hawaii and found itself confronted with a large number of armed and combat-ready islanders. Fortunately, the Rurik in San Francisco had taken on board Elliot de Castro, the personal physician of the King of Hawaii. This was able to mediate before armed conflicts broke out. As a guest of King Kamehameha I, Otto von Kotzebue was able to convince him of the peaceful convictions of his and the Russian Empire.

In the archipelago of the Marshall Islands, the expedition then visited numerous island kingdoms. Mainly the Ratak chain was mapped and attempts were made to bring new sources of food to the locals, who had to live on the rather meager resources of the islands, by growing fruit and vegetables. However, these attempts failed almost completely, because rats devastated the allotment gardens to a large extent and the islanders took farm animals with difficulty. Nonetheless, the relations between the representatives of the two cultures were as open as they were amicable and allowed for lively barter and the handing over of gifts. On departure, a Rataker named Kadu joined the expedition and both naturalists and the captain used the resulting opportunity to learn more about the language, culture and geography of this island world.

On the way back north, the Rurik got into a severe storm that severely damaged the ship. The expedition made it to the safe harbor of Unalaska with difficulty. Three sailors were seriously injured in the storm and the captain's health also suffered. There was not much time to make the ship ready for sea again, because summer was already beginning and so the Rurik was only poorly repaired and equipped for the second summer campaign as quickly as possible.

Summer campaign 1817

The expectations that were placed on the expedition could not be met. The expedition was supposed to find the Northwest Passage based on the coasts and anchorages explored in the summer of 1816. Fifteen Aleutians and a number of small boats were taken on board for this purpose. Should it prove impossible to continue the voyage on board the Rurik , they wanted to leave them at a safe anchorage and continue the voyage with the help of the Aleutians on the small boats. But after the crew on Unalaska and the Pribilof Islands had stocked up on food and equipment, the omens were bad: the winter had lasted a long time this year, the ice melted late and the captain's health began to deteriorate due to the low Temperatures and wet weather increasingly deteriorate.

When the eastern tip of St. Lawrence Island was reached on July 10, the captain of Chukchi learned that the ice in the north had only broken up a few days ago and was slowly drifting north with the current. On the same day the captain lifted anchor and sailed around the island. But ice was spotted in the evening. The master suffered from severe chest pain and was bedridden. The ship's doctor assured the captain that he would be risking his life if he went further north. The condition of the ship was also not ideal to withstand the harsh conditions of the north.

Under these circumstances, the captain decided on July 12th to abandon the expedition's destination and sail home via Unalaska, Hawaii, the Marshall Islands and Manila. This decision was later heavily criticized. At that time, it was unusual, especially on a warship, to make the course of a voyage dependent on the health of the captain if there were other officers (such as Lieutenant Schischmarew) on board who could have taken command. It has also been speculated that the north-drifting pack ice would have opened up after the Rurik dodged to Kamchatka or St. Lawrence Bay. The captain's written order, however, was established and the return journey to Unalaska began.

The Rurik turned around and crossed the Bering Sea, heading for Unalaska, without seeing St. Matthew Island and the Pribilof Islands because of foggy weather. On July 22nd, the Rurik entered the port of Unalaska again.

Return via Manila

During a short stay on Unalaska, the expedition equipment for the north and a large part of the additional Alëuts were disembarked. The Rurik then sailed to Hawaii, where the researchers met the king again. From there the journey went to the Marshall Islands. The reception there was not exuberant, however, as the majority of the men had gone to war against a neighboring island kingdom. Here the Rataker Kadu disembarked again. In view of the unstable situation, the Rurik was only a short distance from these islands. In the rush, attempts were made to lay out a few more gardens and accommodate livestock. Kadu should oversee the maintenance of these new food sources.

The Rurik then sailed to Manila , where the ship, which had been damaged during the north voyage, was repaired in the Cavite shipyard. After a long stay, we went on through the Sunda Strait into the Indian Ocean , which was crossed to the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa. There the Rurik anchored for a short time in Cape Town . The expedition then continued its voyage along the islands of the South Atlantic and returned via the Canary Islands to Portsmouth in England. The last part of the trip was on a direct route to the Kronstadt Fortress and on to Saint Petersburg.

Research work

Already at the beginning of the voyage, Adelbert von Chamisso had to realize with regret that his role as titular scholar on board the Rurik was only of secondary importance. But it was not until the beginning of the summer campaign in 1816 that he began to guess the reasons for this, when he learned that the main, almost exclusive goal of the expedition was to explore the Northwest Passage and that all of his research should only be a decorative accessory to reflect the zeitgeist of the time satisfy who has just demanded that such expeditions be accompanied by scholars. Ultimately, however, it was about “high politics”, namely that Russia was already aware at the time that it would only be able to hold the colonies on the American mainland in the long term if there was a viable sea route was able to tap into the North Sea in order to supply them and to enter into stable trade relationships with them. Since the tsar estimated the likelihood of success to be low, it was left to Count Rumyantsev to finance the campaign.

Chamisso's curiosity, however, did not detract from this situation. From the beginning he collected everything he thought might be relevant to any branch of the science of the day: plants, animals, minerals, bones and handicrafts of the peoples visited. His passion for collecting did not even shrink from human skulls. Wherever he could, he tried to catalog and describe what he found and, last but not least, studied the languages, customs and traditions of the people he met. Here his great love was for the peoples of Polynesia and Micronesia . More than once he had to experience that parts of his collection were destroyed or mutilated by the sailors of his own ship, sometimes willfully, sometimes out of ignorance. But he continued undaunted, and so in the end he managed to bring home a not inconsiderable collection of evidence from a world that was still foreign to Europe at the time.

Since the initiator of the trip, Count Rumyantsev, did not insist on any title to the artefacts he had brought with him, von Chamisso was able to ship them to Berlin at the end of the trip. He donated most of the natural and cultural artefacts that he had collected to the Botanical Garden in Berlin , where he found a job as the second curator . In addition to a volume of the official expedition report, he published his travel diary Trip around the world in 1815-1818 and in 1837 his language study on the Hawaiian language .

After the expedition

The Rurik was sold upon arrival in Saint Petersburg. Otto von Kotzebue wrote a detailed expedition report, which was supplemented by the reports of the individual expedition participants.

After his appointment as captain, von Kotzebue undertook another trip around the world on the Predprijatije from 1823 to 1826 , on which he was accompanied by Johann Friedrich Eschscholtz. They also visited the island chains that they discovered with the Rurik . They found that attempts to introduce new foods and livestock to the islands had largely failed.

The Northwest Passage became less important for Russia. After the various search expeditions for the missing British explorer John Franklin around the middle of the 19th century had proven the insignificance of the north-western passage for shipping, the fur trade on the American west coast began to decline at the same time. The abandonment of the settlements in North America ultimately led to the sale of Alaska in 1867. As a result, the Northeast Passage, newly developed by Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld in 1879 and the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway (1891-1916) served to supply the Russian settlements on the Pacific Ocean directly .

literature

- swell

- Adelbert von Chamisso : Journey around the world , Leipzig 1836, 1st volume: Diary , 2nd volume: Appendix. Comments and views

- Adelbert von Chamisso : Journey around the world. With 150 lithographs by Ludwig Choris and an essayistic afterword by Matthias Glaubrecht. The Other Library, Berlin 2012. ISBN 978-3-8477-0010-4 .

- Voyage of discovery to the South Sea and to the Berings Strait to explore a north-eastern passage: undertaken in the years 1815, 1816, 1817 and 1818, at the expense of Sr. Erlaucht of the Reich Chancellor Count Rumanzoff on the ship Rurick under the Orders of Otto von Kotzebue , Weimar 1821, Volume 1 , Volume 2 , Volume 3 , panels for Volume 1

- Representations

- Louis Choris : Voyage pittoresque autour du monde , Paris 1822.

- Dietmar Henze: Kotzebue, Otto von. In: Enzyklopädie der Entdecker und Erforscher der Erde , Volume 3, 63–69. 5 volumes. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2001. Original edition Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz 1978.

- Otto von Kotzebue: On icebergs and palm beaches 1815-1818. Around the world with the Rurik , Ed. Erdmann, 2004, ISBN 3-86503-005-X .

- Beatrix Langner : The wild European - Adelbert von Chamisso. [Part III: The Journey Around the World], Matthes and Seitz, Berlin 2008.

- August Karl Mahr: The Visit of the 'Rurik' to San Francisco in 1816 ; Stanford, California 1932.

- Edward Mornin: Through alien eyes: the visit of the Russian ship Rurik to San Francisco in 1816 and the men behind the visit ; Bern 2002, ISBN 3-906769-59-3 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Adelbert von Chamisso, Reise um die Welt , p. 34