Moai

Moai (singular: Moai , actually rapanui Moai Maea , 'stone figure') are the colossal stone statues on Easter Island . They are part of larger ceremonial complexes, as they are similarly known from other areas of Polynesian culture. The exact age of the figures is controversial, but it has now been established that they are by no means older than 1500 years. Father Sebastian Englert numbered and cataloged 638 statues, the Archaeological Survey and Statue Project from 1969 to 1976 found 887, but it was probably originally over 1000.

Ceremonial platform

The Moai are not isolated, but are part of a ceremonial complex similar to those found in other areas of the South Pacific - for example Marquesas , New Zealand , Tuamotu Archipelago , Bora Bora , Tahiti , Pitcairn and the like. a. - known as marae . Nevertheless, the facilities on Easter Island are unique in that they are far larger than all other structures in the South Pacific. The typical ceremonial complex of Easter Island in classical times was usually between a village and the coast. Today it is assumed that every village that was inhabited by a clan or extended family had its own complex. It consisted of a leveled area and an ascending ramp paved with gravel (poro) , which led to a rectangular platform (ahu), which was so carefully worked out in megalithic stone setting that in the case of plants of the cultural bloom (for example at the Ahu Tahira in Vinapu ) even today no knife blade fits between the stones. This prompted Thor Heyerdahl to compare him with the Inca walls in Peru . The huge stone sculptures were on the platform with a view of the settlement in front of it - i. H. with a few exceptions with the back to the sea - set up. The figures were erected on flat, cylindrical foundation stones embedded in the ahu and only wedged with small stones. Mortar was unknown on Easter Island.

Purpose of the figures

Despite extensive research, the actual purpose of the statues and the exact time of their erection is still debatable. Today it is assumed that the Moai represent famous chiefs (ariki) or universally revered ancestors who functioned as a link between this world and the beyond. In Hawaii there is the similar sounding word mōʻī , which is applied to particularly high-ranking people at the top of the social and religious pyramid of Hawaiian society. The busts represent specific people from the chief's genealogies, who could once be named. Reports of early visitors to Easter Island and the fact that some Ahu burial chambers were found in some of the Ahu burial chambers suggest a cult of the dead associated with the complex. In the classic times of Easter Island culture, the deceased was wrapped in tapa or totora reed mats and left to decay. Usually this happened on the leveled area in front of the clan's ceremonial complex. When only the skeleton was left, the bones were placed in a recessed chamber of the ahu. However, this form of burial was probably only given to privileged people. The tombs were "guarded" by the stone figures.

Description of the moai

The appearance of the exclusively male statues is uniform at first glance. The oversized head, a third of the entire figure, is delicately designed. A large, carefully formed nose dominates the face under deep-set eye sockets. A broad, protruding chin complements the closed overall impression. The ears with their elongated earlobes are remarkable. The ear plug is also shown here and there. The figures end immediately below the navel, with some statues the maro , the loincloth covering the penis , is indicated. The lower body is not shaped. If you look closely you can see the changing posture of the carefully chiseled hands with unnaturally elongated fingers, which cover the lower abdomen. The figures also differ in the individually shaped loincloth knot (a tattoo according to a different interpretation ) on the lower back. However, these subtleties have not been retained in all figures.

There is evidence that some of the gray-brown statues were originally provided with a pukao , a cylindrical head attachment made of red rock slag. The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich houses a painting by William Hodges , a participant in the Cook Expedition , from 1775/76, depicting moai standing upright and covered with a pukao. The essays probably represent a (ceremonial?) Headdress or a bun. Between 55 and 75 statues were once provided with a pukao. Even if the unfinished moai at Rano Raraku are disregarded, this is a clear disproportion to the total number of statues. A statistical analysis shows that pukao are mostly absent from smaller (less significant) ceremonial platforms. It can therefore be assumed that only moai with a special meaning were put on a pukao. The rock of the Pukao does not come from the Rano Raraku, but from the Puna Pau in the southwest of the island, a side crater of the Rano Kao . The cylindrically shaped head pieces could probably be easily rolled to their destination.

In 1978, during excavations at Ahu Naunau in Anakena, an eye made of white coral limestone with an iris made of red rock slag was found that was originally inserted into the eye socket of a figure. The find is now kept in the Hangaroa Museum. From this find and from the processing of the eye sockets with a "contact surface" on the lower lid, one can conclude that only moai on the ceremonial platforms had eyes that were apparently only added after they were raised to make them "see". The eye sockets of the statues on the Rano Raraku are more simply shaped, so that one suspects that these figures were not (yet) finished.

There is evidence that some of the statues may have been painted in color. Alfred Métraux found traces of red and black paint in a protected place on a figure on the Ahu Vinapu. The specimen in the British Museum also shows slight traces of paint in white and red.

Despite apparently uniform appearance, each figure was individualized. Wilhelm Geiseler reports that a village chief was able to name every single Moai, even the unfinished statues on the Rano-Raraku.

A few moai are additionally decorated, for example an unfinished statue of Rano Raraku has an engraved representation of a ship. The Moai with the name Hoa Hakananai'a ( Rapa Nui for "stolen friend" or "hidden friend") is unique . The figure was found in a house of the Orongo cult site on the rim of the Rano Kao crater and is now in the British Museum in London. The appearance of the basalt sculpture, which is only 2.40 meters tall, corresponds to the usual type, but the back is covered with depictions of bird men, dance paddles ( Ao and Rapa ) and vulvae . The ethnologist Heide-Margaret Esen-Baur considers it the main sanctuary of the Vogelmann cult on Easter Island. Thor Heyerdahl took the view that the figure served as the prototype of all statues of the classical period.

Age of the statues

The exact age of the statues is still unknown today due to the lack of written records. There are indications that the art of stonemasonry developed as early as the first phase of settlement on Easter Island (the time of which is set differently depending on the doctrinal opinion, between 400 and 1200 AD). Smaller (older?) Stone statues of a different type have been found in isolated cases. The synthesis of the original with the culture of the second wave of colonization may have contributed to the essential perfection of the techniques from around 1400 AD, so that it can be assumed that today's colossal figures were created from this point in time. This theory is not without controversy; after Thor Heyerdahl u. a. The formation of the large Moai begins at the time of the first settlement, i.e. at a much earlier point in time. In addition, recent genetic studies raise doubts as to whether there was a second settlement on Easter Island at all.

With the radiocarbon dating examined findings related to the Zeremonialanlagen (human bone fragment earliest dating at Ahu Vinapu 1) dating from 931 to 1812 (latest dating, charcoal at Ahu Huri a Hurenga). The focus of the dating is between 1400 and 1600 AD.

Manufacturing

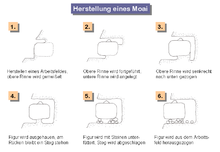

With the exception of 53 smaller moai, which are made of basalt, red tuff and trachyte , almost all of the statues on Easter Island come from the slopes of the Rano Raraku volcano . The mountain consists of a soft tuff stone interspersed with lapilli . With basalt hammers (toki) , some of which can be seen in the Hangaroa Museum, professional stone sculptors - a highly respected class in Easter Island society - carved the statues out of the stone. Thor Heyerdahl has proven experimentally that this could be done in a relatively short time using simple tools and realistic personnel deployment. On the slope and in the crater of the Rano-Raraku there are still 396 statues in various stages of completion, so that the manufacturing process is easy to reconstruct.

The size of the figures probably increased more and more over time. At the Rano Raraku there is a 21-meter-long, but unfinished moai. The largest erect figure with the name Paro on Ahu Te Pito Kura is 9.8 meters high. The statistical mean size of the statues is 4.05 meters, the average weight 12.5 tons.

Transport and erection

After the processing, the (semi) finished statues were lowered down the slope of the Rano-Raraku on ropes. Even today, holes can be found on the crater rim that were used to anchor the ropes to wooden pegs. Halfway up the slope, the stone figures were "temporarily stored" in pits, where they were finished, finely worked and the bridge on the back was completely removed. Numerous more or less finished statues still stand there today.

It was then transported to the final destination. Katherine Routledge discovered real transport routes, carefully leveled, partly heaped or in places even paved roads that led from the Rano-Raraku in all directions. The way of transport is controversial. Tradition reports that the Moai went to the Ahu on their own at night at the instigation of magical persons .

In the meantime, various methods have been experimentally reproduced, both the lying transport with rollers, with wooden rails or with a sledge as well as the upright transport in a beam corset or by rocking movements made with ropes, in which the Moai "walk". In principle, all methods have proven to be feasible. So far, no one has been able to provide definitive proof of the correctness of one or the other method. At the destination, the moai were pulled up the Ahu and erected there with the help of a temporary ramp made of stones . As Thor Heyerdahl has already demonstrated, this is only possible with archaic means.

The moai at Rano Raraku

Around the extinct volcanic crater Rano Raraku there are 396 moai, which today are mostly buried in the ground up to the chest or neck area. The large number of these statues cannot be explained solely by the "interim storage" for later completion. The German ethnologist Hans Schmidt therefore made a distinction between the “Ahu type” and the “Raraku type” as early as 1927 and assumed that it was not at all intended to transport the latter to another location. This is supported by the fact that around 30 statues are placed inside the caldera , a place that would have been extremely unsuitable for further transport to the Ahu on the coast. Katherine Routledge unearthed one of these statues and found that its base was carved in a wedge shape, in contrast to the flat and wider base of the statues on the Ahu.

The American archaeologists John Flenley and Paul Bahn developed the theory from the findings that there were different classes of stone sculptures, depending on the amount of work that the clan was able to pay the professional stone sculptors. The “cheap version” of ancestor worship would have been to set up the Moai on the Rano-Raku, while the much more complex and expensive, but also more prestigious variant would have been to set up an ahu near the village and set up the Moai on a platform.

Destruction of the ceremonial complex

The production of the statues suddenly stopped from one day to the next. At the Rano Raraku, stone tools that were left behind could still be found until recently. The ethnologist Thomas Barthel from the Eberhard Karls University in Tübingen provides a conclusive explanation for this: the construction of large-scale buildings requires a supply and surplus economy, i.e. In other words, the workforce for the production of the moai and the construction of the cult platforms had to be largely freed from the daily procurement of food. A violation of the distribution rules between the artisans and the food suppliers - possibly due to the outbreak of civil war or a change of authorities - resulted in the agreement being terminated and statue production coming to a standstill. This theory also explains a traditional legend of Easter Island. According to this, an old woman, a sorceress, had caught a giant lobster and brought it to the stonemasons at Rano Raraku for consumption, but asked to leave a small piece for her. However, the workers ate all of the lobster and then continued their work. When the woman returned, she was extremely angry and shouted a spell at the stone figures that made them fall over with one blow.

Today most of the ceremonial complexes have been largely destroyed and the Moai have overturned. This is not or not exclusively due to environmental influences. The few systems that are intact today have been restored in recent years.

Jakob Roggeveen describes in 1722 still undamaged and ceremonial ahu. Quote from the report of Carl Friedrich Behrens from Mecklenburg , a marine soldier at Roggeveen's circumnavigation:

“As I found out, they completely relied on their idols, which were erected in great numbers on the beach. They fell down in front of it and worshiped her. These idols were all carved out of stone, in the shape of a human, with long ears. The head was adorned with a crown [meaning the pukao]. The whole thing was done artfully, which we were very surprised about. Around these idols were placed white stones twenty to thirty paces wide. I took some of these people to be priests; for they worshiped idols more than others. They were also much more submissive when worshiping. "

During the Cook Expedition in 1774, the facilities were already neglected and many Moai overturned. Georg Forster , Cook's scientifically educated companion, wrote:

“Fifty paces further we found a lofty place, the surface of which was paved with stones of the same kind. In the center of this square was a one-piece stone pillar designed to represent a human figure, depicted to the waist, twenty feet high and five feet thick. This figure was poorly made and proved that the art of sculpture was still in its infancy here. The eyes, nose and mouth were hardly indicated on the clumsy head, the ears, according to local custom, were incredibly long and worked better than the rest. We found the neck misshapen and short, the shoulders and arms only slightly indicated. On the head was erected a very tall cylindrical stone, over five feet in width and height. This attachment, which resembled the headdress of some Egyptian deities, was made of a different, reddish type of stone. The head and top made up half of the entire column as far as it was visible above the ground. By the way, we didn't notice that the islanders paid homage to these statues ... On the east side of the island we came to a row of seven statues, four of which were still upright, but one of them had already lost its cap. They stood on a pedestal, and the stones in the pedestal were hewn and fitted together well. "

Captain Wilhelm Geiseler from the German hyena expedition to the South Pacific found no more intact facilities in 1882. There are numerous more or less serious speculations about the events in the meantime that led to the destruction of the cult complexes. A turning away from traditional religion is assumed as well as a civil war , a famine , climate and weather disasters, the ecological destruction as a result of the establishment of the Moai or the cultural decline triggered by the Europeans . So far, no one has been able to provide conclusive evidence for one or the other theory, so the cause of the destruction of the ceremonial platforms remains unexplained for the time being.

One of the possible and not entirely absurd interpretations of the events, which Kevin Costner also takes up in his film " Rapa Nui - Rebellion in Paradise ", is based on the fact that the construction of the ceremonial complexes resulted in a competition between the clans and the statues therefore constantly increased in size . The transport and installation consumed more and more wood, until finally all the larger trees on the island were cut down and the production of the moai stopped. The subsequent turning away from ancestor worship and turning to another religion, the Vogelmannkult, triggered the overthrow of the Moai.

Today we tend to see a social upheaval with a change of power between priestly and secular authorities or fluctuations in an unbalanced distribution of power between the clans as the cause of the development of the Vogelmann cult. The extent to which environmental influences played a role is controversial. The moai, symbols of the ancient religion, had lost their meaning.

State today

The majority of the ceremonial complexes are still “ in situ ” today . H. with more or less destroyed platforms and overturned moai. It is noticeable that the Ahu stills are all on the face.

Several ceremonial platforms have been rebuilt from the 1950s, especially in the area of the southeast coast of Easter Island, which is better developed for tourism. Particularly worth seeing is the Ahu Tongariki not far from the Rano-Raraku crater with fifteen upright moai of impressive size, the largest ceremonial complex in the Pacific. The single statue on the Ahu Ko Te Riku in Tahai, near the harbor, is one of the few with a pukao and eyes, which are only replicas from recent times. The well-preserved Ahu Vinapu with its carefully fitted stones is, although not yet reconstructed, a particularly fine example of the architecture of the classical period.

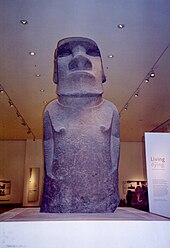

A few, usually smaller, specimens were taken away from Easter Island and set up in other locations in museums or parks on the mainland. Most of the figures exhibited outside the islands or abroad are replicas.

Wooden figures

Moai is also the name given to small, on average forty centimeters high, carved figures from the Easter Island culture, mainly made of Toromiro wood. The most common form, Moai kavakava , shows a starved-looking man with clearly protruding ribs, an oversized, skull-like head , long earlobes, a pronounced nose and a goatee. The purpose of the figures is unknown. Today they are interpreted as ancestral portraits with the function of a protective spirit, possibly they represent Aku Aku .

Most of the surviving wooden figures have an eyelet or hole in the neck area. Captain Geiseler reports that dignitaries wore ten to twenty such figures around their necks during processions. During the rest of the time the portraits were wrapped in tapas bags and hung in the huts.

In addition, other types of moai wooden figures are known:

- Moai papa (paapaa, pa'a pa'a)

- A predominantly female, occasionally also hermaphroditic figure with a less “skeletal” build. Although the vulva is usually clearly defined, the overall appearance of the figure is rather masculine, and some figures even have a goatee.

- Moai tangata

- A more realistic carved male figure, with a slim, boyish build and also a clearly developed goatee.

- Moai tangata manu

- The bird man, a zoomorphic mixture of man and frigate bird . The few statues that have survived are very different, they vary in size, posture, shape of the beak and body structure. A figure in the American Museum of Natural History in New York is covered in Rongorongo characters . The bird man is a frequent motif of the petroglyphs of the Orongo cult site on Easter Island.

The wooden figures are now scattered across museums around the world. In Germany there are moai of various types u. a. in the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Cologne , in the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin-Dahlem , in the Museum für Völkerkunde Dresden and in the Überseemuseum Bremen .

literature

- Heide-Margaret Esen-Baur: Investigations into the Vogelmann cult on Easter Island. Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-515-04062-5 .

- Thor Heyerdahl: Aku-Aku . The secret of Easter Island. Frankfurt am Main / Berlin / Vienna 1974, ISBN 3-550-06863-8 .

- Thor Heyerdahl: The Art of Easter Island. Secrets and riddles. Munich / Gütersloh / Vienna 1975, ISBN 3-570-00038-9 .

- Alfred Métraux: Easter Island. Stuttgart 1958.

- Katherine Routledge: The Mystery of Easter Island. London 1919, ISBN 0-932813-48-8 .

- Thomas Barthel: The eighth country. The discovery and settlement of Easter Island. Munich 1974, ISBN 3-87673-035-X .

Web links

- Data collection of all moai on Easter Island by Britton L. Shepardson, Ph.D.

- Karin Schlott: Colossi should ensure colossal harvests , December 20, 2019 on Spektrum.de

Remarks

- ↑ The exact number can no longer be determined, as some pukao were broken in order to be used again in later graves or in the walls of the ahu.

- ↑ However, this is not the original name of the figure, but refers to the removal by the crew of the British ship HMS Topaze in 1868

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Jo Anne van Tilburg: Easter Island: Archeology, Ecology and Culture. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington 1994.

- ↑ mō'ī in Hawaiian Dictionaries

- ↑ a b c Kapitänleutnant Geiseler, Die Osterinsel - A place of prehistoric culture in the South Seas. Ernst Siegfried Mittler & Son, Berlin 1883

- ^ A b Helene Martinsson-Wallin: Ahu: The ceremonial stone structures of Easter Island , Societas Archaeologica Uppsala 1994

- ^ Alfred Metraux, Die Osterinsel , Kohlhammer Verlag Stuttgart, 1957, p. 132

- ↑ SPON from April 14, 2013: Double life of an Easter Island statue

- ^ Heide-Margaret Esen-Baur, Investigations into the Vogelmannkult on Easter Island , Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden, 1983, ISBN 3-515-04062-5 , p. 151

- ↑ a b Thor Heyerdahl, The Art of Easter Island . Bertelsmann Verlag Munich-Gütersloh-Vienna, 1975

- ^ Patrick V. Kirch, On the Road of the Winds. An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact , University of California Press, 2000

- ↑ a b Patricia Vargas Casanova (Ed.): Easter Island and East Polynesian Prehistory , Istituto de Estudios Isla de Pascua, Santiago de Chile 1999, ISBN 956-190287-7

- ^ A b Katherine Routledge: The Mystery of Easter Island . Cosmo Classics, New York 2005, ISBN 1-59605-588-X (reprint)

- ↑ Angelika Franz: Unearthed - News from archeology: statue walks across Easter Island. In: Spiegel Online . October 28, 2012, accessed June 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Hans Schmidt: The stone picture types of Easter Island and their chronology , Leipzig 1927, pp. 20-21

- ↑ a b John Flenley, Paul Bahn: The Enigmas of Easter Iceland. Oxford University Press 2002, ISBN 0-19-280340-9

- ↑ Thomas Barthel: Das echte Land , Klaus Renner Verlag Munich 1974, ISBN 3-87673-035-X , pp. 301-302