vulva

Vulva (plural: vulvae , Latin vulvae ; also pudendum feminine "female pubic ") denotes the entirety of the external primary sexual organs of female mammals and consists of the pubic mound , the labia and the clitoris . In contrast to animal anatomy , the vaginal vestibule is also counted as part of the vulva in women . From this the vagina leads ( vagina ) inside the uterus (womb) and the short urethra (urethra feminina) to the bladder (Vesica urinaria) . In general, large areas of the vulva are covered by pubic hair (pubes, crinis vulvae) , which develops as part of the body hair and thus as a secondary sex characteristic at the onset of puberty .

Outside of medical terminology, the vulva is also incorrectly referred to as the “sheath” or “vagina”, sometimes also the “outer sheath”. A foreign word also introduced medically and used in literary or sophisticated everyday language is Cunnus (plural Cunni ), which in classical Latin literature was mainly used as an obscene expression or with erotic connotations .

The term “pussy” is often used colloquially . The nickname for cats is also used in other languages for this female sexual organ: English pussy , French chatte , while the Latin cunnus is probably derived from cuniculus "rabbit", similar to the Spanish word conejo for rabbit, which is similar to the vulgarism coño for vulva . The Latin word vulva contains the Indo-European root vélu- , vel ("round, wrap, turn").

The female genital organs of other animal groups - such as the roundworms - can also be called vulva in a biological analogy , but they are completely different from the vulva of mammals.

Anatomy in women

Macroscopic anatomy

Appearance and anatomy of the vulva

The vulva comprises the external, primary sexual organs of women . These are the enclosing parts such as the pubic mound , the large outer labia , the small inner labia, the clitoris and the vaginal vestibule with the outlets of the vagina , the urethra and the vestibular glands . The vagina opens this with the vaginal opening, ostium vaginae or introitus vaginae , more or less pronounced ring-shaped to corona-shaped in the vaginal vestibule , vestibulum vaginae , the vulva. The large labia, labia majora pudendi , run from the mons pubis to the perineum , where they run out into the raphe perinei . They largely cover the clitoris, urethral opening and vaginal entrance and thus protect them. The large labia, labia majora , contain subcutaneous fat tissue to varying degrees and are covered by a pigmented field skin. The skin on the outer surface of the large labia, interspersed with hair , sebum and sweat glands , is pigmented. The skin appendages described gradually disappear towards the inner surface . The skin becomes redder, softer and more like a mucous membrane. Inside, the labia majora contain a lot of fat and connective tissue , smooth muscles , nerves and vessels. Both large labia form the pubic cleft , rima pudendi , their upper junction is called the commissura labiorum anterior , the posterior one is called the commissura labiorum posterior . Due to the different thickness of the subcutaneous fat tissue, among other factors, the inner labia minora protrude to different degrees in a standing woman.

In the formation phase of the organs in the embryo ( organogenesis ), the vulva arises from the genital hump and the sexual bulges lying to the side .

A ) Commissura labiorum anterior of the great labia; B ) clitoral hood, praeputium clitoridis ; the retraction of the clitoral hood , praeputium clitoridis, reveals the clitoral ligament, frenula clitoridis , which continues into the small labia, labia minora ; C ) labia minora , labia minora ; D ) Greater labia, labia majora ; E ) Commissura labiorum posterior of the great labia as well as the perineal suture ( raphe perinei ) and the anus ; F ) glans of the clitoris , glans clitoridis and clitoris shaft, corpus clitoridis ; G ) Inner surface of the great labia, labia majora (see also Fordyce gland ); H ) vaginal vestibule , vestibulum vaginae ; I ) mouth of the female urethra, urethra feminina, the meatus urethrae externus with the carina urethralis vaginae ; J ) Vaginal entrance, introitus vaginae K ) Fourchette, Commissura labiorum posterior

The mons pubis , mons pubis or mons Veneris , and the labia majora , labia majora pudendi , represent the outer boundary of the vulva is Until. Puberty (more precisely pubarche ) they are hairless, in adult women they are with pubic hair covered. The labia majora contain sebum , sweat and odor glands and form the pubic cleft , rima pudendi . The atrial erectile tissue (Bulbus vestibuli) , which is homologous to the male urethral erectile tissue, is covered by the outer labia .

The two small labia minora pudendi , also called nymphae , are located between the outer large labia . In some women in a standing posture, the inner labia minora are completely covered by the outer labia, but often protrude visibly beyond them. Between the large and small labia, a non-fatty layer forms, which is richly equipped with elastic, loose connective tissue and sebum glands. There is no hair at all. Inward to the vestibulum vaginae there is a multi-layered, uncornified squamous epithelium, and outwardly a weakly cornified squamous epithelium. In the connective tissue with its high proportion of elastic fibers , abundant, strong vein networks branch out, which swell when sexually aroused. The clitoris , the "clitoris" , is located on the anterior fold of the inner labia, the anterior commissura labiorum , also known in animal anatomy as the ventral commissura labiorum . The clitoris is an erectile organ formed by cavernous tissue , which is permeated with nerve endings , more precisely mechanoreceptors of the skin , and is particularly able to react to touch . In terms of embryonic development, the clitoris and penis take their common starting point from the genital hump. The clitoris has an externally visible part, the clitoral glans (glans clitoridis) , which is covered by the clitoral hood (Praeputium clitoridis) , as well as two internal corpora cavernosa.

From the lower end of the vulva, the fourchette, commissura labiorum posterior , the adhesions or raphe perinei visibly close in the anteroposterior direction in the median plane to the anus.

The variable appearance of the vulva

Each vulva is individual in its appearance and therefore unique. The size of the clitoris, the labia, the color and surface structure, the distance from the clitoris to the urethral orifice and the distance from the posterior fold of the inner labia, commissura labiorum posterior , to the anus, differ within wide limits. These variations also explain the differences to often post-processed images of external genitalia, which correspond to an idealized ideal of beauty.

The most obvious anatomical difference between different women lies in the shape of the clitoral hood and inner labia and the degree of visibility when the body is in an upright position. Only in a few women are these structures completely enclosed by the outer labia; mostly they protrude more or less strongly.

Due to the rapidly increasing demand for aesthetic intimate surgery and the associated uncertainty of many women, several scientific studies were carried out to determine the normal variation of the vulva. Between August 2015 and April 2017, doctors at the gynecological outpatient clinic at the Lucerne Cantonal Hospital measured the external genital structures of 657 outpatient female patients (15–84 years). The results of the large-scale study were published in 2018. The doctors and scientists found a wide range of variation, particularly in the labia minora, the clitoris and the clitoral hood. Although it was possible to establish statistical parameters, they concluded that there was no such thing as a “normal” appearance, that there was no typical vulva, that the physiological range within a healthy female population was too large. Another study at the University of Colorado School of Medicine , also published in 2018, looked at the same question specifically in adolescents (girls 10–19 years) and came to the same conclusion.

| measured property | Span (in mm) | Mean ( standard deviation ) |

|---|---|---|

| visible length of the clitoris | 5-35 | 19.1 (8.7) |

| Width of the glans clitoridis (glans) | 3-10 | 5.5 (1.7) |

| Distance between the clitoris and the urethral opening | 16-45 | 28.5 (7.1) |

| Length of the outer labia

(front to back ) |

70-120 | 90.3 (10.3) |

| Length of the inner labia

(front to back) |

20-100 | 60.6 (17.2) |

| Width of the inner labia

(from the beginning to the free end) |

7-50 | 21.8 (9.4) |

| Length of the dam | 15-55 | 31.3 (8.5) |

| Color of the vulva compared to the surrounding skin | Number of women |

|---|---|

| equal | 9 |

| darker | 41 |

| Folding of the inner labia | |

| smooth | 14th |

| moderate | 34 |

| pronounced | 2 |

The vaginal entrance and its structures

The inner, small labia include the vaginal vestibule , into which the urethra , urethra femina , opens. In the lower third of the labia minora, the two large atrial glands or Bartholin's glands , glandulae vestibulares majores and several small atrial glands are embedded. They ensure that the vaginal vestibule is moistened. It is in the immediate vicinity of the mouth opening, Meatus urethrae externus of the urethra, into which the paraurethral glands (also called Skene glands) open: These release a thin fluid secretion as part of the so-called female ejaculation . Also in the vestibulum vaginae are the openings of the Bartholin gland, glandula vestibularis major of the great vaginal vestibule, which appear as paired accessory sex glands . They too, but at a different point in time, release a secretion during sexual arousal .

Below this is the entrance to the vagina , introitus vaginae in the animal anatomy Ostium vaginae . It is functionally a vaginal sphincter. With contraction of the surrounding skeletal muscles ( musculus ischiourethralis , musculus ischiocavernosus , musculus bulbospongiosus ) and also through swelling (tumescence), the annular anatomical structure is narrowed. Tears and micro- injuries can lead to dyspareunia . At the transition zone near the vagina between the labia minor , labia minor pudendi up to the vaginal entrance, introitus vaginae , the carunculae hymenales can be found in different forms . Because the vaginal entrance is enclosed in some women by a skin fold, which is called the hymen (also outdated hymen ). After extensive stretching, usually after childbirth, the hymen to the carunculae hymenales can scar . The vulva is supplied with blood via branches of the internal pudendal artery , the nerves of the vulva come from branches of the pudendal nerve (Nervi labiales, Nervus dorsalis clitoridis) . The vaginal entrance and the adjoining vulva represent the end of the birth canal .

Nerve supply to the vulva and the vaginal entrance

The somatic innervation via the voluntary nervous system enables these nerves to act largely voluntarily. The most important nerve for this is the pudendal nerve , also known as "pubic nerve " in German, it arises from the sacral plexus from the spinal cord segments S 1 –S 4 (1st – 4th cross segment) and supplies mostly the female genital organs with general somatosensitive and somatomotor fibers. The nerve runs caudoventrally in the pelvic cavity , that is, downwards and towards the abdomen, in the direction of the pelvic floor (pelvic outlet), together with the internal pudendal artery and vein via the infrapiriform foramen in the pudendal canal ("Alcock's canal"). The pudendal nerve has several branches:

- Nervi rectales inferiores (caudales) , they innervate the area around the anus and the muscle sphincter ani externus (external anal sphincter ).

- Nervi perineales , also called “dam nerves”, supply the perineum with sensitivity and the muscles ( musculus ischiourethralis , musculus ischiocavernosus , musculus bulbospongiosus ) . The bulbospongiosus muscle is a sphincter muscle that surrounds the vulva and the vaginal vestibule , introitus vaginae . It is therefore also subdivided into the constricor vulvae and the constricor vestibuli muscle . The ischiocavernosus muscle , through its work of compression or contraction, inhibits venous blood outflow from the corpus cavernosum clitoridis through the deep clitoral vein , thereby improving congestion in the entire clitoral organ. They also supply the striated muscle around the urethra , the urethral muscle . The Nervi perineal care also has the Nervi labial the labia minora , labia minora pudenda .

- The dorsal clitoral nerve , known as the "back of the clitoris", is the direct terminal branch of the pudendal nerve and the most important sensory nerve of the glans of the clitoris , the glans clitoridis .

Another important nerve is the ilioinguinal nerve , which arises from the lumbar part, lumbar plexus of the lumbar and cruciform plexus ( plexus lumbosacralis ) at the level of the segments Th 12 to L 1 ; it also carries general somatosensitive and somatomotor fibers. He innervated parts of the abdominal muscles and the skin of the labia majora , labia majora pudenda . Its two branches are:

- Rami musculares , they supply the lower sections of the abdominal muscles, the musculus transversus abdominis and the musculus obliquus internus abdominis .

- Nervi labiales anteriores , they supply the large labia , labia majora pudendi . Its sensitive branches also nourish the skin on the lower abdomen.

In summary, the general somatosensitivity can be described as follows: The pubic mound , mons pubis , and the upper part of the labia majora pudendi , located in the direction of the clitoral hood , are supplied by the ilioinguinal nerve . It comes from the spinal cord segment at level L 1 . In contrast, the lower, in the direction of the perineum, and the posterior part of the great labia, labia majora pudendi , the clitoris and the small labia minora pudendi , are innervated by the nervi labiales posteriores from the nervus pudendus . They arise from the spinal cord segments at the level S 2 -S 3

The vegetative innervation by the vegetative nervous system occurs primarily through the uterovaginal plexus , it is a nerve network ( plexus ) for the innervation of u. a. Uterus and vagina . This term refers to a vegetative nerve plexus in the female pelvis. The so-called Frankenhauser ganglia are also located here . In terms of space and anatomy, it borders closely on the inferior hypogastric plexus . The inferior hypogastric plexus contains not only sympathetic but also parasympathetic fibers and is connected to the abdominal aortic plexus and the superior hypogastric plexus . From the latter the sympathetic fibers pass over both sides of the hypogastric nerves to the inferior hypogastric plexus . Switching to the second neuron of the sympathetic fibers takes place not only in the inferior hypogastric plexus , but also partially in the inferior mesenteric ganglion . The parasympathetic nerve fibers originate from the second to fourth sacral nerves and pass via the splanchnic nerves pelvici to inferior hypogastric plexus .

The vegetative nervous system regulates the vital functions (vital functions) such as heartbeat, breathing, digestion and metabolism and thus also the functions of organs and organ systems, including sexual organs, the endocrine glands (hormones), the exocrine glands , in order to maintain the internal balance ( homeostasis ) (such as sweat glands ), the blood vessel system (fullness or congestion, blood pressure) and the like. Sexual stimulation is transmitted via the pudendal nerve , or more precisely the nerve dorsalis clitoridis and nerves labiales led to the parasympathetic core areas in the sacral spinal cord, from here are reflex over the parasympathetic nerve fibers, the splanchnic nerves Pelvi pulses to the clitoral cavernosa and the introitus performed, the erect or at least enlarge due to an increase in blood volume. At the same time, the parasympathetic nerve fibers activate the mucous secretion of mucus in the accessory sex glands . But also the enlargement of the posterior vaginal vault, fornix vaginae , and the straightening of the uterus, uterus , are among the reflex responses of sexual stimulation.

The starting points of this sexual excitement are the corpuscular receptors at the introitus vaginae, the inward, medial surfaces of the labia minora, the carina urethralis vaginae and clitoris, such as the Ruffini corpuscles , Merkel corpuscles and the Vater-Pacini corpuscles and free nerve endings ( Mechanoreceptors of the skin ). Such structures are absent or very few in the interior of the vagina.

Microscopic anatomy

In terms of tissue , the uppermost layers of most parts of the vulva consist of multi-layered, non- keratinized squamous epithelium , which, however, tends to become keratinized and atrophy in old age . The inner sides of the inner labia have a non-keratinized squamous epithelium, the outer sides a weakly keratinized. A multilayered, mostly keratinized squamous epithelium is found covering the inside, a keratinized one on the outside of the outer labia. In the lamina propria of the vaginal vestibule, there are sebum glands that form a protective film against the effects of urine . Such sebum glands are also found in the inner and outer labia. The latter also have hair root cells , sweat glands and smooth muscle cells . A particularly large number of sensitive nerve fibers and endings , such as the Meissner body , can be found in the labia and clitoris.

Structure of the female skin (vulva) with its appendages ; the appendages are distributed differently over the respective anatomical structures

The upper layers of the skin (cornified squamous epithelium ) as a microscopic ( histological ) preparation

A Meissner corpuscle (tip of the black pointer) in the light microscope. Its localization in the stratum papillare of the corium is easy to recognize.

The vestibulum vaginae is delimited inwardly, i.e. medially, by the outer part of the hymenal ring. Downwards, i.e. towards the anus , and laterally, laterally, from the so-called Hart line or Hart's line . It is not visible macroscopically . It represents the lateral edge of the vestibulum vaginae and describes ( histologically ) the transition from non-keratinized squamous epithelium to the slightly keratinized epithelium. It is the boundary between the “inside” and the “outside world” ( endoderm and ectoderm ).

Comparative anatomy

As a rule, only the external genital organs of higher mammals are named as vulva , although the term is also used in scientific literature for functionally comparable ( analogous ) structures in other animal groups such as roundworms (Nematoda) .

In mammals, with the exception of monotons , the exit of the urinary and genital orifice is separated from the intestinal anus by the perineum . Monotremes do not have a vulva or vagina, the two wombs (uteri) and the urethra open together with the intestines into a cloaca . Cloaks are created during embryonic development in all mammals, including humans. In the pouch and placenta animals , it is later separated by a layer of tissue, the urogenital septum, into a front area with the genital organs and the urinary bladder and a rear area with the anus.

Anus, perineum and vulva of a horse (Haflinger mare)

Normal swelling in a female baboon

Vulva of an Asian elephant cow (Elephas maximus)

The basic structure of the vulva differs only slightly within mammals. A significant peculiarity of the human vulva consists in the presence of the outer, large labia majora : Most mammals have only one pair of labia, which comparatively anatomically corresponds to the small labia, labia minora of women, as homology . In animals , the pubic bone does not bulge out as a mons pubis . In most animals, the vaginal vestibule is significantly longer than the space delimited by the labia, so that the vaginal vestibule is not counted as part of the vulva in the Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria . The hymen, which is only a delicate ring fold in many mammals, is therefore not part of the vulva either. In numerous mammals, the clitoris foreskin is firmly attached to the glans, so that no clit pit is formed.

A special feature of the genital area, which is individually quite variable (comparable to humans), is the so-called flashing or blinking of the vulva, a rhythmic opening and closing of the vulva, in female odd- toed ungulates such as equids ( horses , donkeys and zebras) and tapirs Labia with the clitoris becoming visible during the willingness to mate and mostly after urination (see also pheromones ).

For comparison, vertebrates such as birds , reptiles ( Sauropsida ) or even basal mammals ( Protheria ), such as the monotremes , have a cloaca and its corresponding external shape. An organ like a vulva does not exist. While in the higher mammals the cloaca is only created embryonically and in the further course of the ontogenetic development differentiates into separate body openings for the intestine and for the urogenital tract , this embryonic development phase continues in the vertebrate groups mentioned above until a permanent organ system has developed.

Visible cloaca of the red-tailed buzzard

Cessus of a fox cloak (Trichosurus vulpecula)

Occasionally, however, atavisms occur in humans, for example in the form of a persistent cloaca.

Ontogenetic development

The development of the external genitalia in women starts with a sexually indifferent phase. Then from the 12th week of pregnancy (SSW) the differentiation for the two sexes ends. In the indifferent phase, the following anatomical structures are first created:

- Genital cusps, they lie ventral to the cloacal membrane

- Genital or urethral folds, they are on both sides of the cloaca membrane ( cloaca )

- Genital ridges or labioscrotal ridges, they unfold laterally to the genital folds

The urogenital membrane is formed between the genital folds, which initially closes the urogenital ostium . After the urorectal septum has grown together with the cloacal membrane, the membrane tears and releases the ostium. The genital hump initially grows in length in both sexes and becomes a cylindrical organ, essentially formed from maturing erectile tissue.

This cylindrical structure does not grow any further in the female sex and remains as a clitoris; in the male it differentiates into the later penis. The genital tubercle , tuberculum genitale , is the original and common attachment of the clitoris and penis. It arises from an overgrowth of the mesenchyme cranioventral (head-belly side) of the cloacal membrane. Under the influence of androgens, the phallus elongates in male individuals and the urogenital groove closes to the pars spongiosa of the urethra and forms the erectile tissue of the urethra. In the later woman, the “protophallus” remains short and differentiates itself into the clitoris. The urogenital folds remain separate in the female and form the inner, small labia. The urogenital groove, sulcus urogenitalis , arises on the underside of this "protophallus" and is bounded by the two urogenital folds, plicae urogenitales . On the side of the genital protuberance, the aforementioned sex bulges develop - the joint attachment of the outer, large labia, labia majora , but also the scrotum , the scrotum. The genital folds now merge in the rear section to form the frenulum labiorum pudendi , from which the labia minora emerge later .

The tissues of the genital bulges thus unite front and rear, where they create the commissura labiorum anterior and posterior and thus also the later pubic mound, mons pubis . The labia majora also have their origin here.

Prenatal

During the first eight weeks of embryonic development, male and female embryos have the same rudimentary sex organs. This period is therefore also referred to as the indifferent stage . In the sixth week, the genital hump and the urinary tract develop . After the eighth week, the embryo's hormone production starts and the genital organs begin to develop in different directions. Nevertheless, the differences are almost invisible until the twelfth week. When testosterone is formed and the receptors ( steroid receptors ) in the tissue are intact, a male external genitalia develops under its influence. If there is a lack of testosterone, a female genital will develop. During the third month, the clitoris develops from the genital hump. The urogenital folds form to the inner labia, the labioscrotal bulge to the outer labia.

Neo- and postnatal

Immediately after birth, the external visible structures of the genitals are often swollen and disproportionately large. This is due to high levels of maternal hormone exposure. The swelling usually subsides a few days after the birth and the vulva returns to its normal size. Subsequently, the vulva will hardly change structurally throughout childhood up to the beginning of puberty, except that it will grow proportionally to the entire body.

Development in puberty

During puberty , the vulva undergoes a significant change, as the external genitals also react to sex hormones . The skin color (pigmentation) changes, and the structures of the vulva become larger and more pronounced. This development affects the clitoris and the inner and outer labia, but especially the hormone-sensitive skin of the vagina and its atrium. In the area of the vulva, that is on the mons pubis and the vulva, begins at puberty, the growth of pubic hair .

The shape of the vulva varies from person to person. The clitoris can be partially visible or completely hidden, or the inner labia can be larger than the outer ones. This difference is not a pathological phenomenon, but normal.

Changes after menopause

After menopause , dystrophic changes of the vulva of varying degrees can occur, in particular a decrease in fat tissue with a decrease in skin thickness. There is a regression of the labia, a shrinking of the clitoris, a narrowing of the vaginal entrance and dry skin of the vulva. These changes are caused by the decrease in the body's own production of estrogen , even though the vulvar tissue is much less responsive to estrogens than that of other organs.

physiology

Physiological changes in the vulva as a whole occur primarily before and during sexual intercourse and during the birth of the offspring. Because they are equipped with sebum , apocrine sweat and scent glands , the areas between the labia, the clitoris and the vaginal vestibule lead to constant formation of sebum and sweat , which moisturize the mucous membranes of the genitals. Sebum and impurities can settle in the folds of the mucous membrane of the vulva and form what is known as smegma . The smegma of the vulva is a mixture of sebum glands that comes from the Tyson glands , a form of free (ectoptic) sebum that does not open into hair follicles or a hair follicle, and that is found in the folds of skin between the outer and inner labia and around the clitoral hood (preputium clitoridis) are around. It is precisely these skin folds, which lie close together, that the release of heat, evaporation of fluid and the removal of the abraded epithelium are hindered, so that a warm, moist, predominantly anaerobic environment with a neutral to slightly alkaline pH value can arise. This is also where a wide variety of pheromones are believed to be released. The copulins are among the most intensively studied pheromone candidates in primates . These are mixtures of volatile, short-chain fatty acids ( aliphatic monocarboxylic acids ) that occur in female vaginal secretions depending on the cycle . Copulins were first described in rhesus monkeys by Richard Michael and colleagues in the late 1960s and early 1970s, respectively .

Change in the vulva during the sexual cycle

In many mammals, changes in the vulva also occur during the sexual cycle , the extent of which varies depending on the species and the individual. The rutting phase occurs either once a year (monostrically) or several times (polyostrically). The concentration of the hormone estrogen is then highest in comparison to the progesterone in the blood in this phase. At the beginning of oestrus (oestrus), in most mammals , in addition to other physiological changes, such as increased production of cervical mucus and the like. a. m., to swelling and reddening of the vulva due to increased blood flow, as can be observed, for example, in the normal swelling of various primates.

Changes in the vulva in the sexual response cycle and during intercourse

With the onset of sexual arousal , there are numerous physiological changes in the vulva that, taken together, prepare the female genital tract for sexual intercourse. The reactions are divided into different, chronologically consecutive phases: the excitation phase, plateau phase, orgasm phase and regression phase.

The arousal phase can last for several hours and is triggered by mechanical stimulation or sexually arousing stimuli (including psychological such as sexual ideas or dreams). The phase is characterized by increased blood flow to the structures of the vulva. This is caused by a vasoconstriction of the draining, venous blood vessels, it leads to a swelling of the clitoris and the atrial erectile tissue ( erection ), the skin turns darker.

The onset of lubrication , i.e. an increasing secretion of secretion from the accessory sex glands , which intensifies in the plateau phase. The lubrication is used to moisten the vagina and labia and facilitates penetration and sliding of the penis into the vagina. The mechanical irritation of the vaginal skin by the inserted penis increases the erection of the vulva and leads to swelling of the lower vaginal wall.

The orgasm phase is accompanied by muscle contractions of the pelvic floor muscles . Immediately before orgasm, the glans of the clitoris retracts under the clitoral hood. The clitoris is often very sensitive immediately after orgasm, and additional stimulation can be uncomfortable.

In the regression phase following the orgasm, there is again an outflow of blood from the region caused by vasodilation . The structures swell again, the moisture goes down and the normal state is restored.

Estrogens promote the development and growth of the labia minora , labia minora pudendi , further increasing the vascularization and generally the tumescence of the vulva with a proliferation of the covering them epithelium . In addition, the estrogens stimulate the accessory sex glands , such as the Bartholin's gland , glandula vestibularis major , but inhibit the sebum glands . In contrast, the large labia , the clitoris, and the mons pubis are more under the additional influence of androgens . The estrogens promote the keratinization of the keratinocytes in the vulva epidermis , while androgens and progesterone inhibit them.

Changes in the vulva during pregnancy

Especially in the last trimester of pregnancy, many women have increased pigmentation of the linea alba (then, depending on the severity of the discoloration, called linea nigra (black line) or linea fusca (brown line)), the areolas ( Areolae) and the vulva. This is probably caused by an increased secretion of the melanocyte-stimulating hormone . These are some of the likely signs of pregnancy . In addition, congestion of the veins in the pelvis can lead to swelling and the formation of varicose veins in the area of the vulva ( varicosis vulvae gravidarum or varicosis vulva in graviditate ).

Changes in the vulva during childbirth

During childbirth , contractions and the associated opening of the cervix and the birth canal (opening phase of childbirth) mainly lead to a softening of the vaginal muscles, which allow them to stretch during the later birth process (expulsion phase of birth). This strain also concerns the Vorhofschwellkörper and the tissue of the labia and the dam, which may crack under the strain ( laceration ) and is cut at birth may ( episiotomy ).

Physiological microbiome of the vulva

Every human body surface as well as every externally connected internal body surface has its own individual bacteriome. That is the part of the bacterial genetic information in the microbiome.

The natural microbiome denotes - here in the vagina-vulva system - in a broader sense the entirety of all microorganisms that colonize humans. In a narrower sense, this denotes the entirety of all microbial genes or genomes (DNA) in the human organism and differentiates it from the term microbiota, which denotes all microorganisms. The skin of the vulva is thinner than on other parts of the body, so the epidermis has only a narrow zone of keratinization . While the labia majora are interspersed with hair or hair follicles , which are accompanied by sebum and apocrine glands , only sebum glands are found on the labia minora, but no hair or follicles. These anatomical characteristics influence the composition of the corresponding microbiome.

The vulva following the vagina, like the rest of the body, is also populated by a bacterial flora or a microbiome, the composition of which varies little from one individual to the other, but depends on the female hormonal cycle. They form the physiological or normal flora . A “healthy” or physiological microbiome often determines the health or disease of the vulva.

The vagina opens with the vaginal opening, ostium vaginae or introitus vaginae , into the vaginal vestibule , vestibulum vaginae , which represents the "connecting zone" between vagina and vulva. Changes in the pH value occur here. The vaginal epithelium builds up cyclically under the influence of estrogens , which leads to the intracellular storage of glycogen in the epithelium, which serves as food for the predominant lactobacillus flora ( Döderlein bacteria ), the dominant germs in the vagina. The normal flora of the vagina includes the facultative organisms such as lactobacilli , corynebacteria , propionibacteria , streptococci group B, E. coli , Staphylococcus epidermidis and Gardnerella vaginalis , Veillonella , as well as anaerobes such as Peptococcus , Peptostreptococcus and Bacteroides . However, isolated yeasts, such as the Candida group, can also be found. If this complex equilibrium is disrupted, potentially pathogenic organisms are able to multiply in excess and can then lead to symptoms of the disease, the vagina, vaginitis ( bacterial vaginosis ) or vulvovaginitis . The normal vaginal flora influences the bacterial colonization of the vulva ( skin flora ).

The smegma of the vulva is a mixture of sebum secretions with abraded epithelium, which is located in the superficial folds of skin between the outer and inner labia and around the clitoral hood , preputium clitoridis . In these interlabial niches, a warm, humid, predominantly anaerobic environment with a neutral to slightly alkaline pH value is created. The degree of heat release and evaporation of transudates and sweat ultimately depends on the size (surface) of the closely spaced skin folds . These physical factors affect the microbiome of the vulvar surface.

The smegma is made up of cell debris from the dead and abraded surface epithelium , fatty acids , steroid derivatives (such as cholesterol esters ), proteins and microorganisms . As everywhere in and around the human body there is a specific and typical microbial resident flora , such as yeasts of the Malassezia or the mycobacteria scoring Mycobacterium smegmatis , also called "Smegmabakterium" (see also microbiome of man ).

Medical aspects

Malformations

Vulvar malformations belong to the genital dysplasias . They mainly show up in the area of the vaginal vestibule. Here, in particular, there are forms of the hymen that close the vaginal entrance over a large area or, in the case of hymenal atresia , completely. In the area of the urethral orifice , abnormalities such as stenoses , hypo- and epispadias occur. A clitoral hypertrophy may also be present as a malformation or a sign of a hormonal disorder in the context of other diseases. Adhesion of the labia majora, so-called labia synechiae , is caused by the hormonal calm in childhood or by inflammation. They therefore represent more of an inflammatory disease.

Diseases

A number of different diseases can occur in the vulva, some of which can also involve the internal genitals.

Inflammation, infection and infestation

The skin regions, which are different in their structure, with horny and hair-bearing skin in the area of the outer labia and the mound, the finer skin of the small labia and the moist mucous membrane in the vaginal vestibule , vestibulum vaginae or introitus vaginae , lead together with the anal region due to their microclimate and the high Dampness to diseases more common than other parts of the body. Acute and chronic inflammation are among the most common diseases of the vulva. If this inflammation only affects the external genitals, it is called vulvitis ; more common is a joint inflammation of the vulva and vagina ( vaginitis ) called vulvovaginitis . Vulvitis can be triggered by external influences such as toxins, incompatible underwear or tight pants, allergic reactions , increased discharge ( genital fluorine ), metabolic disorders and toxic substances.

Another cause of inflammation is infections with viruses , bacteria or fungi . Among the viruses, the human papilloma viruses (HPV), the herpes simplex viruses (HSV-1 and -2) and the molluscum contagiosum virus play a role. The most common bacterial infections are caused by Streptococcus pyogenes , Staphylococcus aureus ( folliculitis , pseudofolliculitis ), Corynebacterium minutissimum ( Erythrasma ), gonococci and Chlamydia trachomatis . Among the fungi, Candida albicans ( candidiasis ) and Trichophyton rubrum ( tinea of the vulva) are of particular importance. Some of these infections can also cause more serious illnesses. Gonococci are the causative agents of gonorrhea , while human papillomaviruses are the main cause of warts , genital warts , erythroplasia and cervical cancer , a cancer of the cervix . An infection with Treponema pallidum leads to syphilis (syphilis), the primary effect of which is found in vaginal intercourse on the labia or in the vagina.

Parasite infestation, for example with pubic lice ( Phthirus pubis ) or scabies mites ( Sarcoptes scabiei ), is also known.

Forms of elephantiasis , more precisely elephantiasis of the vulva, occur in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world . These are infestations with the roundworm , Wuchereria bancrofti (Cobbold, 1877), which lives parasitically in the lymphatic vessels of humans.

A closure of the duct of the Bartholin's gland leads to a pseudocyst due to the accumulation of secretion. Bacterial infection often leads to bartholinitis .

In animals, a number of can cover diseases such as the cold sore horses that dourine of horses Infectious pustular vulvovaginitis in cattle (IPV), which Trichomonadenseuche of cattle, the canine transmissible venereal tumor of dogs and the rabbit syphilis manifested on the vulva. Taylorella equigenitalis , the causative agent of contagious uterine inflammation in horses , can persist for years in the indentations of the clitoris.

Genital warts of the vulva

Vaginal discharge from gonorrhea

Louse infection of the pubic hair

Chronic diseases

Different influences can lead to different forms of vulvar dystrophy , changes in the transitional epithelium with cornification or shrinking of the skin with largely unexplained causes. Most forms of vulvar dystrophy, for example kraurosis , also called lichen sclerosus , occur after the onset of menopause (climacteric).

Some vulvar dysplasias are associated with atypical cells and represent precancerous lesions that can lead to malignant (malignant) vulvar tumors . These precancerous stages are also known as vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). They usually develop between the ages of 60 and 80 and are located in the labia majora. A "vulvar cancer" can form metastases . More than 90% of the tumors are squamous cell carcinomas ( vulvar carcinomas ); the remaining 10% are basal cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, melanomas or carcinomas of the Bartholin's glands. But sarcomas can also be found. Therapy is performed surgically by removing areas of the vulva ( vulvectomy ). More often, however, it is lipomas and fibromas that form as benign tumors in different areas of the vulva.

Vulvodynia , which is characterized by long-lasting painful conditions in the labia majora and other parts of the vulva, is a disease of as yet unexplained cause . It is similar to vaginodynia (pain in the vagina) and is classified together with it as a chronic genital pain syndrome . Hormonal changes, for example during menopause, and psychological causes are discussed as triggers.

By chronic venous insufficiency of the pelvic veins, especially the vena ovarica can varicose veins , similar to the male varicocele develop.

Advanced neurofibromatosis of the vulva

Histology of atrophic lichen sclerosus

Histology of hypertrophic lichen sclerosus

Medically indicated operative changes

The complete or partial surgical removal of the large and small labia and other parts of the vulva and the underlying tissue is called a vulvectomy . It may be necessary in cancer of the vulva , rarely in advanced vulvar dystrophy in older women. In a radical removal of treating a cancerous condition also can lymph nodes of the groin (inguinal lymph nodes) and the basin are removed (pelvic lymph nodes). A partial vulvectomy can also be performed in the case of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia .

The surgical removal of the clitoris is known as a clitoridectomy , although a medical indication due to specific cancer diseases is rare.

Linguistic aspects

etymology

The word vulva goes back to the Latin volva , vulva ("uterus", botanically also "shell" of fruit), which in turn is uncertain in its etymology . It is either traced back to an Indo-European root * vélu-, vel, "encircle", "envelop", "rotate", "turn" together with Latin volvere "roll", " wälzen ", "turn" and then an Indo-European word * vlvo "shell", " egg skin ", "womb" added, which also resulted in Sanskrit úlva-m, -s (also ulba-m, -s ) "egg skin", "womb". Or you can take from the However, late in Edictum Diocletiani occupied word form lat. Volba a common root with the word clan Greek δελφύς "uterus" ἀδελφός "brother", δέλφαξ "piglets" at.

In classical Latin, volva, in contrast to today's medical meaning, initially referred to the uterus , in culinary contexts specifically the uterus of the pig, which was considered a special delicacy. Even Pliny the Elder distinguished between uterus as the name for the human uterus and volva as that for the uterus of animals. As the uterus increasingly displaced vulva as a name for the uterus, the meaning of vulva in the sense of cunnus was shifted or narrowed to the external genital area, with os vulvae ("mouth of the vulva") since Cornelius Celsus as the name for the external opening.

The late antique etymology started with this changed meaning; Thus, in the 6th century AD , Isidorus derived vulva from valvae , "wing doors", since they let the semen in as if through a door and through it the fetus emerges.

Other names

On the one hand there are a large number of expressions for "vulva" on the other hand, the genitals of women are subject to a lot of shame, so much so that women often have no name for it and shamefully describe it as "secret place" or "around the bottom". This is expressed directly in the terms "the pubic" (for vulva) or " labia " (instead of lust or Venus lips ). More distant slang words are: "sheath" or Latin " vagina ", more precisely referred to as "outer sheath" (because sheath correctly describes the internal organ behind the vulva).

"Pussy" is used more lovingly. The nickname for cats is also used in other languages : English pussy , French chatte .

" Cunt " is used hard to disparagingly . The Swiss couple therapist and non-fiction author Klaus Heer has collected a large number of other derogatory terms, often derived from a mechanical way of thinking and language , for example "Dose, Büchse, Bohrloch, Klemme, Bumskerbe".

Cultural aspects

The vulva in a cultural context

Symbolized vulvae from different epochs and cultures.

- Above left: pubic triangle in Sumerian cuneiform munus (means "woman");

- Above right: Hindu symbol for yoni .

- Bottom left: Pointed oval appeared in many contexts as a representation or symbol of the vulva.

- Middle: oval within oval (as a variation of 3).

- Bottom center: Egyptian hieroglyph used for "woman" and "vulva".

- Bottom right: Czech and Slovak “Píča” symbol ( piːtʃa ).

In general and across cultures, the vulva is associated with the biological functions of sexuality and childbirth. However, social attitudes towards the vulva differ in some cases considerably between different cultures and historical epochs.

Public interaction and taboos

In different cultures there are taboos with regard to the vulva, which for example limit public visibility, the representation in art or even the conversation about the vulva. The attitudes vary from being completely taboo through association with sin or disgust on the one hand, to an objective and relaxed attitude as a “completely normal part of the body” to adoration and deification as a symbol of fertility and the place of origin of life.

Until the late Middle Ages, public interaction and the depiction of the vulva was comparatively open and the attitude was positive in the Christian-Occidental culture. This changed with the beginning of the modern era and reached its climax in the so-called Victorian era of the 19th century: a generally strong prudery and physical hostility went hand in hand with a negative, hostile position towards the vulva. This development was reversed in the 20th century, initially with the life reform movement and intensified with the sexual revolution of the 1960s. In the course of increasing liberalization of society, female emancipation and a more relaxed attitude towards sexuality, taboos on the vulva were removed.

Social norms and ideals of beauty

In addition to morally justified taboos with regard to public presentation, there are great differences with regard to aesthetic ideas: which anatomical characteristics and cosmetic changes are perceived as beautiful is strongly influenced by culture.

The attitude towards pubic hair is very different. Pubic hair is perceived as beautiful in some regions of the world, while in other cultures pubic hair is rated as unhygienic and repulsive. Pubic hair removal has been established in western culture since the 1990s and has since become an established part of personal hygiene.

Various anatomical structures such as the inner and outer labia, clitoral hood and mons pubic are subject to ideals of beauty. There are different ideals around the world with regard to the characteristics of the inner labia:

“Most women in Europe consider it beautiful when the outer labia just cover the inner labia minora . In Japan, on the other hand, a butterfly-winged appearance of the labia is considered ideal, in some African countries a particularly long protrusion of the inner labia is considered. "

In numerous cultures, the labia are adapted to the respective ideal of beauty by stretching or surgically removing tissue. In the last few decades there has also been a steadily growing demand for cosmetic surgeries in the intimate area in Europe .

In Western European culture, the vulva has increasingly been the subject of aesthetic standards since the end of the 20th century: while this body region was previously considered private and hidden, today it is increasingly subject to public scrutiny and "should look beautiful".

Attitudes of men and women towards the vulva

In 2018, Erich Kasten , psychologist and professor of neuroscience at the Medical School Hamburg , investigated the question of what attitudes and aesthetic preferences exist with regard to the vulva and whether these differ between women and men. Study participants were asked to state their subjective assessments and evaluations. In addition, the reactions to photographic images of the female genitals were recorded in various forms. The background to the study was the widespread dissatisfaction and insecurity among women with regard to the appearance of their vulva and, as a result, the rapidly increasing demand for cosmetic surgeries in the genital area, in particular labia reduction .

The result showed a clear preference for a complete removal of pubic hair. There was no gender difference: men and women found the vulva to be the most aesthetic with a complete intimate shave. Trimmed and partial depilation was found to be acceptable, whereas complete, natural pubic hair was rated as neglected and unattractive. There were clear gender differences with regard to the size of the inner labia. Women showed a strong preference for weak inner labia that do not protrude above the outer labia. In contrast, the preferences of men were less clear: men rated both large and small inner labia as similarly “erotic” and “aesthetic”.

“In the data presented here, large labia minora were rated significantly better by men than by women. What is striking is the high negative mean value for the women surveyed in contrast to the positive mean value for men. This means that vulva with large inner labia were rated significantly more negatively by the participants than by men [...] These results show that men rate differently than women. "

The attitude towards the outer labia as well as the clitoris and clitoral hood showed the same difference in preferences, although less clearly.

There was no connection between the assessments with previous sexual experience in men or with personality traits (the open-mindedness dimension of the five-factor model ) in men or women.

Traditional circumcision of the vulva

Today, the clitoridectomy is mainly performed in connection with the circumcision of female genitals. In some cultures, mainly in Africa , the circumcision of female genitals is used as a cultural practice. This mutilation is carried out for social and cultural reasons . The extent of the operation varies from removing the clitoral hood to completely removing the external genitals and suturing the vagina.

Because of the far-reaching consequences for the life and limb of the girls and women concerned, this practice has long been criticized by human and women's rights organizations around the world. Numerous organizations, including the United Nations , UNICEF , UNIFEM , the World Health Organization (WHO) and Amnesty International , oppose circumcision and classify it as a violation of the human right to physical integrity . To emphasize these aspects, the term female genital mutilation has been established internationally .

Aesthetic-cosmetic changes in the vulva

Modifications to the vulva can be made for a variety of cultural and aesthetic reasons. As a rule, it is about adapting to a personal or culturally shaped ideal of beauty or a body norm. They range from the removal of pubic hair to procedures in which parts of the vulva are removed through invasive procedures.

Pubic hair removal

The most widespread modification in western culture is partial or complete pubic hair removal. The practice is documented in other cultures or for earlier epochs of Western culture. The Islam expects the removal of pubic hair. Around the turn of the millennium, 1999/2000, the practice became more widespread in the West. According to a survey from 2009 in Germany, shaving the genital area was quite common among the 18 to 25 year olds (69.7% of women). The intimate shave is not without its problems. Women who shave without following the natural direction of growth are more prone to hair root inflammation .

Cosmetic genital surgery

As an operative measure, some women have a labia reduction (labiaplasty) make, the inner labia, and sometimes also the prepuce ( clitoral hood reduction ) reduced, or removed, increasing the labia majora, the introitus narrowed a hymen reconstructed or the position of the clitoris to be changed. This happens mainly from subjective aesthetic, occasionally from socio-cultural, rarely also from medical motives. Therefore, the majority of these interventions are summarized under the name of cosmetic genital surgery (Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery (FGCS)). Surgical measures in the context of gender reassignment, gender reassignment in the case of intersex people or the circumcision of female genitals are not counted as part of the FGCS.

Piercing

Piercings also represent a form of body modification , whereby various structures of the vulva can be provided with jewelry. Just like genital shaving , the trend towards genital piercings can be seen as a result of the increased establishment of social and aesthetic norms for the pubic area, "a body region that was previously primarily private - the pubic region - is now subject to a design imperative." While some piercings of the vulva are positive Have an impact on the stimulability of women during sexual intercourse, most piercings have a purely aesthetic function. As with other parts of the body, piercings can cause complications. The most common problems of piercings in the female genital area are inflammation , tears and bleeding. Allergies , excessive scarring ( keloids ) and foreign body granulomas are also not uncommon.

The vulva in art

The vulva has regularly found its way into art and culture, particularly because of its sexual relationship and its function as part of the birth path. She is considered a symbol of fertility (“great mother”) and at the same time a symbol of desire. In addition to the Paleolithic depictions of women ( Venus figurines ), whose vulva is emphasized, there are also more recent rock carvings , particularly in the caves around Fontainebleau in France , which often depict vulvae.

In some cultures the presentation of the vulva was understood apotropaically as a magic defense against evil forces.

The same or similar symbols that represent a vulva appear again and again in different cultures . Numerous representations from the Paleolithic Age testify to similar cultic-worshiping attitudes in Europe. However, the cultural attitude towards the female genital differs between different cultures. While in some cultures the vulva is taboo and covered in public, other cultures showed a cult around the vulva. So this was worshiped in festivals and considered sacred.

During excavations between September 5 and 15, 2008 in the Hohle Fels cave on the Swabian Alb, a woman's statuette carved from mammoth ivory from the Aurignacia period, the so-called Venus vom Hohlen Fels, was discovered . It was found that the vulva was emphasized between the open legs, which was interpreted as a “deliberate exaggeration of the sexual characteristics”.

In the Middle Ages , especially in Ireland, so-called Sheela-na-Gig , stone sculptures , which depict the vulva, mostly oversized and spread out, were created above the entrances to monasteries and castles . Vulva ornaments can also be found on church facades from the High Middle Ages, while pilgrim insignia and utensils from the Late Middle Ages depict vulvae and penises in different variations, such as a cloak needle with a vulva equipped as a pilgrim with arms, legs and a hat. The purpose of such utensils is no longer known, they are interpreted both as parodies of conventional pilgrim badges and as good luck charms.

The yoni cult developed in Hinduism , which together with the male lingam symbolizes the bisexuality of the god Shiva , belongs to the vulva cults. Together with the lingam, the yoni represents the symbol of spontaneous generation .

Stylized Stone Age illustration of the vulva in Saint-Germain-en-Laye , Stone Age

Sheela-na-Gig at the Church of St Mary and St David in Kilpeck, Herefordshire

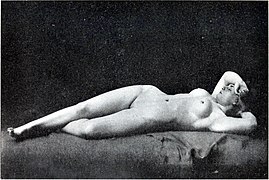

European art history up to the 19th century

In European art history, starting from ancient Greece and earlier cultures, the concrete depiction of the vulva was largely avoided in both painting and sculpture until the late 19th century. This mainly affected the ancient statues of the Greeks and Romans , exceptions were rare pornographic depictions of heterosexuals, for example in Greek vase painting and murals (see prostitution in antiquity ).

The representation of naked bodies in Italian and Italian-influenced art in the 14th to 17th centuries, which flourished again with the Renaissance, and the further development in Europe up to the end of the 19th century, continued this practice. All the well-known painters and sculptors of the period who depicted nudes, including Antonio Pisanello , Raffael , Tizian and Giambologna , Peter Paul Rubens , and painters of French salon art such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Jean-Léon Gérôme, as well as Impressionism such as Edgar Degas or Auguste Renoir showed the mons pubis, but no further anatomical details.

Exceptions were the painters of the German and Dutch-speaking areas such as Jan van Eyck , Lucas Cranach the Younger , Hans Baldung Grien , Jan Gossaert and Albrecht Dürer , who usually used their nudes in painting, graphics and sculpture (especially in the form of miniatures made of wood and ivory ) with natural pubic hair and pubic cleft. Here the depiction was primarily due to the desire for a more realistic and complete depiction and took place primarily in the depiction of biblical motifs such as the depiction of Adam and Eve or portraits of Mary without sexual reference. In his proportional schemes for the ideal female body, Dürer also devoted himself to the weybs gap and represented it accordingly. This form of representation disappeared in the 16th century when the idealized and gender-concealing state was adopted in northern Europe as well.

There are a number of theories about the reasons for the lack of hair and detail in the representation of the female sex, which were first developed by Denis Diderot and later in the 20th century; Diderot and a few other authors mainly use aesthetics in form and color as a reason, while others, following Sigmund Freud's theory, used the fear of the threatening female gender.

In the 18th century, primarily pornographic depictions with artistic aspirations were created by lesser-known artists such as Eugene Poitevin and Jean-Jacques Lequeu , who as an architect also adorned buildings with detailed drawings of female genitals. Nudes with pubic hair were only occasionally accepted in an artistic context, for example in Francisco de Goya's painting The Naked Maja (around 1800–1803). The painting L'Origine du monde ( The Origin of the World , see below) by Gustave Courbet has been exhibited at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris since 1995 , a commissioned work from 1866 that was only shown privately for a long time. The oil painting shows a slightly open vulva with dark pubic hair. Although this image is one of the oldest known works with a detailed depiction of the vulva, its late publication had no impact on contemporary art at the time of its creation. Courbet himself, like other artists of his time, did not depict the vulva in detail in other nudes.

In the 19th century, painting and sculpture based on the female nude model increasingly came into fashion and into art academies, so that the real representation of gender became more present for artists. At first it was mainly shown in preliminary studies and sketches, but disappeared when it was implemented in painting. In particular, the studies by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres , who became famous for depicting smooth, marble-like female bodies, show the armpit and pubic hair that is no longer visible in the later paintings. Photographs were also used as a template, such as by Jean-Léon Gérôme , whose Phryne before the judges in 1861 was probably painted from a photograph by Felix Nadar . At the end of the 19th century, these realistic elements appeared in individual artists - such as Gustave Caillebotte and the American Thomas Eakins - in the pictures.

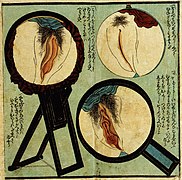

Japanese art

In Japan , clay figures of fertility goddesses with enlarged genitals were made in the early days more than 4000 years ago. In Shintoism , the phallus was the focus of creation mythology and it was also the main motif of the erotic depictions of the Heian period from the 8th to the 12th century.

In the 17th to 19th centuries during the Edo and Meiji periods , the very revealing Shunga pictures, or literally spring pictures, established themselves as a variant of the colored woodblock prints ( Ukiyo-e ) , whereby the term spring is a metaphor for sex . There are paintings, prints and pictures of every kind that explicitly depict sexual acts and also show the details of the sexual organs. At the same time, the term shumbon ( Japanese 春 本 "spring books") came into use for books of sexual content. A central motif in it were the courtesans , who were educated not only in prostitution , but also in poetry, writing and tea. With the opening of Japan to the Europeans and the importation of Western moral concepts, bathing men and women in public baths and the trade in erotica were banned in 1868. At the end of the Meiji period in 1910, both the production and distribution of the shunga, which had meanwhile been perceived as obscene, were made a criminal offense. Until 1986 it was forbidden in Japan to show even the beginnings of pubic hair in public. Uncensored Shunga exhibitions have only been back since 1994.

Katsushika Hokusai : Fukujusō ( Amur Adonis Flower ), 1815

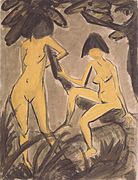

20th century art

While photography and film prevailed at the end of the 19th and increasingly at the beginning of the 20th century and numerous nudes were also circulated, these were not regarded as art, but were generally considered pornography. Detailed depictions of the pubic region or pubic hair in painting, however, were frowned upon; violations led to scandals at the beginning of the 20th century. In March 1901 the Viennese Secession's Ver Sacrum magazine was confiscated and destroyed by the public prosecutor's office because it contained some drawings by Gustav Klimt that “exceeded the limits of what was socially sanctioned”. His designs for ceiling friezes at the University of Vienna were rejected because of anatomical details, and Klimt was referred to as a scandal painter in contemporary literature. Other artists were also sanctioned; In 1917 an exhibition by Amedeo Modigliani , the only one during his lifetime, was closed by the police because the files were considered pornographic due to the pubic hair depicted.

Pubic hair in particular became a symbol of the avant-garde of nude painters and later became the center of attention, the representation of female bodies without pubic hair or pubic cleft completely disappeared from modern art of the 20th century. In particular, Pablo Picasso , Egon Schiele and George Grosz place the female and male genitals prominently in the foreground of their nude art and make them socially acceptable. Based on this, representations of the vulva as well as the penis and the sexual act in the erotic art of painters such as Balthus , Marcel Duchamp and André Masson , photographers such as Robert Mapplethorpe , Man Ray and Helmut Newton to Jeff Koons , Gerhard Richter , Gottfried Helnwein and Pierre Klossowski were made as well as the Japanese Nobuyoshi Araki and many others.

Otto Mueller : Two female nudes on a tree , 1923

Egon Schiele : Woman with Black Stockings , 1913

Gustav Klimt : Woman masturbating , 1913

present

Images of the female genitals can be found in contemporary art in many genres, especially in nude photography and erotic photography , along with a taboo on representation. This freedom of movement has also found its way into portrait photography , with the women depicted presenting both their face and their vulva, in serial full-body portraits or double portraits of face and vulva.

The vulva also plays a prominent role as a symbol of liberated female sexuality in feminist art, where its depiction in conjunction with floral or butterfly motifs has shaped the style of Georgia O'Keeffe and Judy Chicago, among others . In particular, Judy Chicago's dinner party , the confrontation of the representation of female genitals with baroque portraiture by Zoe Leonard at Documenta IX , the gigantic figure Hon - en katedral (Swedish: "She - a cathedral") by Niki de Saint Phalle in front of the Stockholm Moderna Museet that could be entered through the vulva, the assemblies of prostheses and sex toys by Cindy Sherman and the provocative performances by the Austrian artist Valie Export such as the Aktionhose Genitalpanik (1969), in which she walks through the rows of spectators with pants cut out in the area of the genitals Sex cinema went, as well as other works by Carolee Schneemann , Hannah Wilke , Marina Abramović , Chloe Piene and Annie Sprinkle belong in this context.

In web-based media art, u. a. the project Vagina Museum from Vienna is worth mentioning.

Megumi Igarashi, 43, was on trial in Tokyo in April 2015 for profanity after she 3D printed a kayak in the shape of her vulva and sent the file to investors in her project. In 2016, she was acquitted of her design for a kayak because, in the words of the BBC report, her depiction does not immediately suggest female anatomy because of the bright colors. However, because of the 3D data of her vulva, she was fined 400,000 yen (several thousand euros), since they had the shape of her vagina, probably vulva, reconstructed.

|

|

||

|

|

||

Mithu Sanyal did her doctorate on the cultural history of the female genitals. The book “Vulva. The unveiling of the invisible gender ”.

literature

Medicine and physiology

- Günter Strauss: Vulva. In: Willibald Pschyrembel , Günter Strauss, Eckhard Petri : Practical gynecology for studies, clinics and practice. 5th, revised edition, De Gruyter, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-11-003735-1 , pp. 1–31.

- Miranda A. Farage, Howard I. Maibach: The vulva: anatomy, physiology, and pathology . CRC Press, London 2006, ISBN 0-8493-3608-2 ( full text in Google Book Search).

- V. Küppers, Hans Georg Bender : Blickdiagnostik Vulva . Elsevier, Urban & Fischer, Munich a. a. 2003, ISBN 3-437-23270-3 ( full text in the Google book search).

- Eiko E. Petersen: Color Atlas of Vulvar Diseases. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis . Kaymogyn, Freiburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-00-043086-2 .

- Abdel Fattah Youssef: Youssef's Atlas of Gynecological Diagnoses . Fischer, Stuttgart / New York 1985, ISBN 3-437-10976-6 .

- Constance Marjorie Ridley, Sarah M. Neill, Fiona M. Lewis: Ridley's The Vulva . Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester UK / Hoboken NJ 2009, ISBN 978-1-4051-6813-7 .

Cultural history

- Hans Peter Duerr : Intimacy . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-518-38835-5 . Pp. 200-255.

- Hans Peter Duerr: Obscenity and Violence . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-518-38951-3 . Pp. 82-119.

- Agnès Giard: L'imaginaire érotique au Japon . Albin Michel, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-226-16676-0 .

- Mithu M. Sanyal: Vulva. The unveiling of the invisible gender . Wagenbach, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-3629-9 .

- Lih Mei Liao, Sarah M Creighton: Requests for cosmetic genitoplasty: how should healthcare providers respond? In: BMJ. May 26, 2007, Volume 334, pp. 1090-1092, doi: 10.1136 / bmj.39206.422269.BE .

- Cheryl B. Iglesia, Sheryl Kingsberg: The Quest for the "Perfect" Vagina. In: The Female Patient. Volume 34, February 2009, pp. 12-15, obgynnews.com (PDF).

psychology

- Claudia Haarmann: "Downstairs ..." The shame is not over . Inner World, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-936360-15-4 .

Colloquial language

- Klaus Heer: delightful words. Lustful kidnapping from sexual speechlessness. Revised new edition. Salis, Zurich 2007, ISBN 978-3-905801-02-6 (with dictionary for female and male genitals and sexual activities), klausheer.ch ( memento from August 31, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF).

Web links

- Video on 3sat : Vulva and vagina - New insights into female pleasure. ZDF 2020 (43:43 minutes; available until May 14, 2025).

- Video by scobel : Vulva: lust and taboo. ZDF, May 2020 (57:49 minutes; discussion with Ann-Marlene Henning , Mithu Sanyal and Sheila de Liz; available until May 14, 2025).

- Kerstin Rajnar: Vaginamuseum.at.

Individual evidence

-

^ Professional Association of Gynecologists : Outer Genitalia of Women. In: Frauenaerzte-im-netz.de. March 26, 2018, accessed May 15, 2020;

Harriet Lerner: “V” is for vulva, not just vagina. In: LJ World.com. May 2003 (English);

Stephan Maus: Vulva: The secret sex organ. In: Stern.de. April 22, 2009;

Florian Borchmeyer: "That down there" - "Vulva": The cultural history of the female sex. ZDF broadcast aspects . February 13, 2009. - ↑ Vagina & Vulva: The Center of Lust! ( Memento from May 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) In: Bravo.de .

- ↑ Rauber , Kopsch : Textbook and Atlas of Human Anatomy. Department 4: Guts. 13th edition. Thieme, Leipzig 1929, pp. ??.

- ↑ Wilfried Stroh: Sexuality and obscenity in Roman "poetry". In: Theo Stemmler, Stephan Horlacher (eds.): Sexuality in Poems: 11th Colloquium of the Research Center for European Poetry. University of Mannheim 2000, ISBN 3-8233-4156-1 , pp. 11-49.

- ↑ Real Academia Española: Diccionario de la lengua española de la Real Academia Española. digital version of the 22nd edition, Madrid 2011, input keyword coño On: buscon.rae.es ; accessed on September 20, 2015.

- ↑ Richard Riegler: The animal in the mirror of language. Books on Demand , Norderstedt 2014, p. 87.

- ↑ Vulva. In: Pschyrembel Dictionary Sexuality. De Gruyter, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-11-016965-7 , p. 581.

- ^ A b Arne Schäffler, Nicole Menche: Human - Body - Illness. Biology, anatomy, physiology. Textbook and atlas for healthcare professions. 3rd revised and expanded edition, Urban & Fischer, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-437-55091-8 , pp. 396-397.

- ↑ GH Schuhmacher, G. Aumüller: Topographische Anatomie des Menschen. Urban & Fischer, Munich / Jena 2004, ISBN 3-437-41366-X .

- ↑ Gerhard Aumüller et al .: Duale Series Anatomie , 2nd edition. Thieme, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-152862-9 , p. 728.

- ^ Theodor Heinrich Schiebler: Textbook of the entire human anatomy: cytology, histology, history of development, macroscopic and microscopic anatomy. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg / Berlin / New York 2013, ISBN 978-3-662-12240-2 , p. 524.

- ↑ Gerhard Aumüller et al .: Duale Series Anatomie , 2nd edition. Thieme, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-13-152862-9 , p. 728.

- ↑ a b J. Lloyd, NS Crouch, CL Minto, Liao LM, SM Creighton: genital appearance Female: "normality" unfolds. In: BJOG. No. 112, 2005. PMID 15842291 , doi: 10.1111 / j.1471-0528.2004.00517.x , pp. 643-646.

- ↑ a b Ada Borkenhagen, Heribert Kentenich: Labia reduction - the latest trend in cosmetic genital correction - review article. In: Obstetrics and gynecology. No. 69, 2009, pp. 19-23, doi: 10.1055 / s-2008-1039241 .

- ↑ There are five different types of vaginas, and they are all wonderful . On: mtv.de/news (Viva) from October 29, 2018; accessed on May 20, 2020.

- ^ The standardized gender - Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

- ↑ More and more teenagers want a labia surgery - Bunte

- ↑ Michala, L., Koliantzaki, S., & Antsaklis, A. (2011). Protruding labia minora: abnormal or just uncool ?. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 32 (3), pp. 154-156 doi: 10.3109 / 0167482X.2011.585726

- ↑ What does a "normal vulva" actually look like?

- ↑ A. Kreklau, I. Vaz, F. Oehme, F. Strub, R. Brechbühl, C. Christmann, A. Günthert: Measurements of a 'normal vulva' in women aged 15–84: a cross ‐ sectional prospective single‐ center study. In: BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology , 2018, doi: 10.1111 / 1471-0528.15387

- ↑ KE Brodie, VI Alaniz, EM Buyers, BT Caldwell, EC Grantham, J. Sheeder,… PS Huguelet: A Study of Adolescent Female Genitalia : What is Normal ?. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology , 2018, doi: 10.1016 / j.jpag.2018.09.007

- ↑ Representation of the individual accessory glands in women. ( Memento from December 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (drawing) urologie3400.at

- ↑ Tara R. Franke: A bubbling source of pleasure: The glands of the female urogenital tract. In: German Midwives Newspaper. Elwin-Staude-Verlag, October 2007 ( PDF: 18 MB, 15 pages on hebammenhandwerk.de ( memento of November 29, 2014 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Anna Knöfel Magnusson: Vaginal corona: Myths surrounding virginity: your questions answered. Brommatryck & Brolins AB, Stockholm 2009, ISBN 978-91-85188-43-7 , pp. ?? (English; PDF: 544 kB, 22 pages on rfsu.se ( Memento from May 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Pschyrembel , 256th edition. Berlin 1990: “ Carunculae hymenales myrtiformes: myrtle leaf-shaped remains of the destroyed hymen; generally after births. "

- ^ Roche Lexicon Medicine. 4th edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich 1999.

- ↑ a b Theodor H. Schiebler, Horst-W. Korf: Anatomy: histology, history of development, macroscopic and microscopic anatomy, topography . Springer, 2007, ISBN 3-7985-1770-3 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Hymen. In: Pschyrembel Dictionary Sexuality. De Gruyter, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-11-016965-7 , pp. 225-226.

- ↑ a b c d Uwe Gille: Female sexual organs. In: F.-V. Salomon et al. a. (Ed.): Anatomy for veterinary medicine. 2., ext. Edition. Enke, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8304-1075-1 , pp. 379-389.

- ^ Van AT Ginger, Christopher J. Cold, Claire C. Yang: Structure and Innervation of the Labia Minora: More Than Minor Skin Folds. In: Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery. Volume 17, number 4, July – August 2011, pp. 180–183 ( PDF: 1.2 MB, 4 pages on iscgmedia.com ( memento of December 22, 2015 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ The nerve innervation. (Photo) From: Georgine Lamvu u. a .: Vulvodynia: An Under-recognized Pain Disorder Affecting 1 in 4 Women and Adolescent Girls - Integrating Current Knowledge Into Clinical Practice. In: CME / CE. 4th January 2013.

- ↑ Roland Schiffter: Neurology of the vegetative system. Springer, Heidelberg / Berlin / New York 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-93269-4 , pp. 112–118.

- ↑ Per Olov Lundberg: The peripheral innervation of the female genital organs. In: Sexology. Volume 9, No. 3, 2002, pp. 98-106, sexuologie-info.de (PDF).

- ^ Van Anh T. Ginger, Claire C. Yang: Functional Anatomy of the Female Sex Organs. In: J. P. Mulhall et al. a. (Ed.): Cancer and Sexual Health. (= Springer Science, Current Clinical Urology. Volume 13). doi: 10.1007 / 978-1-60761-916-1 2 pp. 13-23, beck-shop.de/fachbuch/leseprobe (PDF).

- ↑ Roland Schiffter: Neurology of the vegetative system. Springer, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-93269-4 , p. 104.

- ↑ D. Müller: On the problem of corpuscular receptors in the area of the internal female genitals. In: Gynaecologia. Volume 159, No. 3, 1965, pp. 143-152, doi: 10.1159 / 000303507 .

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Ahrendt, Cornelia Friedrich (ed.): Sexualmedizin in der Gynäkologie. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 2015, ISBN 978-3-642-42060-3 , p. 19.

- ↑ Daniel Baumhoer, Ingo Steinbrück, Werner Goetz: Histology . Elsevier, Urban & Fischer, 2003, ISBN 3-437-42231-6 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Renate Lüllmann-Rauch: Pocket textbook histology . Thieme, 2006, ISBN 3-13-129242-3 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ D. Berry Hart, AH Barbour: Hart's line. In: Manual of Gynecology. Edinburgh 1882; “The hymen separates the external genitals from the internal genitals” on: hymen-virgin-membrane.com ; accessed on March 14, 2016.

- ↑ Manfred Dietel: Pathology: Mamma, Female Genitalia, Pregnancy and Children's Diseases. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg / New York 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-04564-6 , p. 254.

- ↑ Michael K. Hohl , Gudrun Mehring: Painful Vulva: Vulvodynia, Vestibulitis. In: Frauenheilkunde aktuell. (FHA), January 21, 2012, ISSN 1663-6988 , pp. 4-16. kantonsspitalbaden.ch ( Memento of March 13, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF).

- ↑ E. Szabó, B. Hargitai, A. Regos and a .: TRA-1 / GLI controls the expression of the Hox gene lin-39 during C. elegans vulval development. In: Developmental Biology. Volume 330, No. 2, 2009, pp. 339-348. PMID 19361495 .

- ↑ Nadja Møbjerg: Organs of osmoregulation and excretion. In: W. Westheide and R. Rieger: Special Zoology. Part 2: vertebrates or skulls. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-8274-0307-3 , p. 151.

- ↑ Hartmut Greven: Reproduction and Development. In: W. Westheide, R. Rieger: Special Zoology. Part 2: vertebrates or skulls. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-8274-0307-3 , p. 151.

- ^ Robert Pies-Schulz-Hofen: The zoo keeper training. Parey, Singhofen 2004, p. 474.

- ↑ C. Aurich: reproductive medicine in horses: gynecology - andrology - obstetrics. Parey, Sindhofen 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Compare the evolution of mammals

- ↑ Milton Hildebrand, George Goslow: Comparative and functional anatomy of the vertebrates. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-18951-7 , pp. 328-335.

- ↑ Altaf Begum, Afzal Sheikh, Bilal Mirza: Reconstructive Surgery in a Patient with Persistent Cloaca. Casereport. In: APSP J Case Rep. , 2, 2011, p. 23, PMC 3418031 (free full text)

- ↑ U. Drews: Gender Development. In: Karl-Heinrich Wulf , Heinrich Schmidt-Matthiesen (Hrsg.): Clinic for gynecology and obstetrics. Volume 1: Gynecological Endocrinology. 2nd Edition. Urban & Schwarzenberg, Munich a. a. 1987, ISBN 3-541-15010-6 , pp. 3-24.

- ↑ Miranda A. Farage, Howard I. Maibach: The vulva: anatomy, physiology, and pathology . CRC Press, 2006, ISBN 0-8493-3608-2 ( full text in Google book search).

- ^ A b V. Küppers, HG Bender: Blickdiagnostik Vulva . Elsevier, Urban & Fischer, Munich a. a. 2003, ISBN 3-437-23270-3 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ A. Mewitz, E. Knaute, S. Hennig, N. Berger: What influences the sexual behavior of older and older people and what influence does this have on care? GRIN, 2008, ISBN 3-640-13688-8 ( full text in the Google book search).