Vertebrate pheromones

Pheromones in vertebrates are secretions of substances which, as olfactory signals, cause specific changes in behavior or physiological responses in an animal of the same species. Territory markings or readiness to mate are examples of effects that are also attributed to pheromones in vertebrates. Because of the unexplained chemical nature of the cocktails of substances used by vertebrates, the statements in this area are speculative. For some substances that are considered pheromones, the chemical composition has been clarified as well as the physiological path that these messenger substances take to the corresponding sensory cells (to Jacobson's or vomeronasal organ ), for others the results of research are still open. It is difficult to distinguish it from other forms of chemical communication.

etymology

The chemist Peter Karlson and the zoologist Martin Lüscher coined the term pheromone in 1959 and defined it as follows:

"Substances that are released from an individual to the outside and trigger specific reactions in another individual of the same species"

After almost 20 years of work, in 1959 Adolf Butenandt succeeded in the final extraction and purification of the first known and proven insect pheromone , bombykol, from the glands of more than 500,000 female silk moths . For insects, the effects of pheromones are largely well understood.

The transfer of the definition by Karlson and Lüscher to the mode of action of messenger substances in vertebrates, however, led to an ongoing scientific discussion due to the difficult differentiation from other behavior-determining processes. Based on the classic definition with regard to the application to humans or vertebrates, Beauchamp suggested various criteria that a substance should meet in order to be considered a vertebrate pheromone. According to this, vertebrate pheromones should be species-specific in their effect, be genetically determined, be composed of only one or a few components, produce a reproducible, observable behavior or cause endocrine reactions and be tested against control substances.

Other authors, however, defined the term pheromone for chemical substances that are released by an individual and transport information to one or more other individuals of the same species.

Control of mating behavior in hamsters

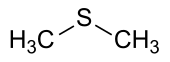

In the golden hamster ( Mesocricetus auratus ), pheromones have been identified that control mating behavior. Dimethyl sulfide is from the female during estrus apart and attracts a male. When the two hamsters meet, the male stereotypically first smells the female's cheek gland, then the flanks and finally the genital area, while the female signals readiness for mating by rigid posture (lordosis). Lordosis can be triggered in sows by androgenic steroids.

Hamsters' vaginal secretions also contain the protein aphrodisin , which contains a previously unknown, low-molecular, hydrophobic substance. When aphrodisin is detected by the male's vomeronasal organ , copulation is initiated.

Control of the reproductive cycle of mice

The presence of other mice affects the reproductive cycle of the female mice. Substances from the urine of male or female mice regulate, among other things, the formation of gonadotropic hormones.

- Pheromones from female family members delay puberty in young females.

- Pheromones from female family members slow down the cycle.

- Pheromones from foreign males induce puberty. (Vandenburg Effect)

- Pheromones from unrelated males speed up the cycle.

- Pheromones from competing males trigger miscarriages.

- Pheromones from males have a regulating effect on the menstrual cycle in females, as 20 percent more luteinizing hormone is produced (Whitten effect)

- Female pheromones synchronize the female menstrual cycle (Lee-Boot effect)

Territory marking and the scents of musk deer and the civet cat

Muscon is formed by the musk deer ( Moschi moschiferus ) in a gland on the belly in front of the genital organs together with at least 9 other substances of the musk . It is used to mark the territory. Because of its characteristic smell, it is used in the cosmetics industry (now synthetically produced). It was used by the deer to mark their territories.

Diluted civetone from the civet of the civet ( Viverra civetta ), which in its natural state has a very unpleasant smell, is also used in the manufacture of cosmetics. Along with civetone, civet contains indole and skatole . Civet also serves to mark the territory of the civet cat.

The MUP ( major urinary protein ) darcin as a male pheromone in wild mice

In wild mice, the females are attracted by a protein in the male's urine: darcin . This binds to ( S ) -2- sec -Butyl-4,5-dihydrothiazole (SBT), a volatile molecule that also has pheromone properties. Because darcin, like aphrodisin, is a lipocalin , it can bind a low molecular weight ligand like SBT. Together with SBT, darcin can act as a fragrance. Without SBT, darcin is still a pheromone, but no longer volatile.

Darcin signals to female mice the presence of a dominant (and therefore attractive) male. At the same time, Darcin induces a learning process in the female animals, which learn the individual odor nuances of the urine of precisely this male. Receptors for darcin are found in the vomeronasal organ .

Farnesol and Nutrias

In 2007, Attygalle and others were able to analyze the substance ( E , E ) - Farnesol from the anal scent glands of Nutrias and prove, through its use in bait , that Farnesol has an attractive effect on the animals. The work grew out of the problem of controlling the spread of nutrias in the wild and resulted in an effective solution.

Further examples

An example of an alarm pheromone in rats is 2-heptanone . In dogs, pheromones are present in the urine, which are used to mark the territory.

Pheromones in humans

Possible participation of the olfactory receptor hOR 17-4 in the targeting of the sperm

Studies have shown that the receptor hOR 17-4, which is expressed in the middle part of the sperm , responds to bourgeonal , a fragrance of the lily of the valley , and enables the sperm to orientate itself in a concentration gradient of this substance. The receptor is also expressed in the nose. It is still unknown which substance is the natural ligand of the receptor.

Possible synchronization of the menstrual cycle in women

There are few well-controlled studies on pheromones in humans. The synchronization of the female menstrual cycle , which is supposed to be caused by unconsciously perceived odorous signal substances, the Lee-Boot effect , has long been considered the best studied . In women who lived together for long periods of time, the menstrual cycle seemed to coincide. Two types of (still unknown) pheromones should be involved: one that is produced before ovulation and shortens the menstrual cycle, and another, produced precisely at ovulation, that extends it. Recent studies could not confirm a synchronization of the menstrual cycle.

Different reception of body odors in the hypothalamic region depending on sexual orientation

Using the activity of the hypothalamus , Swedish researchers have shown that the brains of homosexual and heterosexual men react differently to two body scents that may be associated with sexual arousal, and that homosexual men respond to them like heterosexual women. Pheromones could therefore play a role in the biological basis of sexual orientation .

Possible role of the histocompatibility complex in partner choice

Humans use olfactory signaling substances that work together with the immune system to look for partners who are not closely related to them ( assortative pairing ). Human women, like female fish and mice, prefer partners with a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) that is as different as possible from their own, which means that their children generally have a more varied and thus stronger immune system.

After becoming pregnant or taking hormonal contraceptives , the effect is reversed: women then prefer men with similar (closely related) MHC. The pill makes the woman's hormonal system think she is pregnant and in this state women are apparently looking for family-like partners who can help them raise their offspring.

No pheromone peptides are known to date.

Volatile steroids and short chain fatty acids as possible pheromones

In mammals, the origin of the pheromones lies mostly in the so-called apocrine sweat glands ( Glandulae sudoriferae apocrinae ). These scent glands are mainly found in certain areas of the skin - such as the armpits or the armpit hair , the nipples ( glandulae areolares ), the perianal - and the genital region . Men emit androstenone , a remodeling product of the sex hormone testosterone , which reaches the surface of the body via the apocrine sweat glands ("scent glands"). Test series have shown that androstenone dosed in moderation slightly improves the rating of the attractiveness of men. Men are more attracted to women when they ingest certain female sex pheromones, especially around ovulation .

Female primates and women produce what are known as copulins . Copulins are mixtures of volatile, short-chain fatty acids ( aliphatic monocarboxylic acids ) that occur in female vaginal secretions depending on the cycle . Copulins were first described in rhesus monkeys by Richard Michael and colleagues in the late 1960s and early 1970s, respectively . Human vaginal secretions are those of other primates very similar and contain - in different compositions - the same volatile ( C 2 - to C 6 - ) fatty acids. The proportion of such fatty acids in vaginal secretions varies over the course of a sexual cycle ; overall, the content increases in the first half of the menstrual cycle , then decreases again.

In addition, the production rate varies from person to person. For example, some women only produce a small amount of these copulins, and hormonal contraceptives also seem to have a reducing effect on the secretion of copulins. The highest concentration is reached shortly after ovulation .

In men, olfactory exposure to copulins leads to a change in the testosterone concentration in saliva and to a change in the assessment of the sexual attractiveness of women.

Technical recovery and agricultural industry

There are perfumes with synthetically produced pheromones. According to the manufacturer, they increase the erotic attraction to the opposite sex. The effects are controversial. The use of pheromone-like musk or musk- like substitutes as a fragrance in cosmetics and detergents is widespread .

In the industrial agriculture is about the androstenone, it is - together with skatole responsible for boar taint of - Ebers used in animal production. In the intoxicated sow it induces the rigor of tolerance . Boar smell in meat products occurs only in about every tenth animal and only in cooked meat products, but not in raw meat and sausage products. The boar fattening , with the androstenone test following the slaughter, is therefore an alternative to piglet castration (see also pig production ).

Pheromones in popular culture

The largely unexplained facts about the effect of pheromones in vertebrates have been exploited in various ways in popular culture to explain extraordinary effects with their help.

- Star Wars : The Trap Species uses their pheromones to psychologically influence other humanoid species.

- Star Trek : female orions can secrete a sex pheromone

- The Jitterbug Perfume by Tom Robbins

- Snakes on a Plane : Snakes become aggressive with pheromones and attack the passengers of an airplane

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

- Batman & Robin : Poison Ivy , played by Uma Thurman , uses a pheromone extract to manipulate men

- Predator 2 : the alien can be tracked down through a pheromone signature

- Dietmar Dath : The abolition of species

- The swarm : Protozoa use pheromones to command them to merge

- Ocean's 13 : Linus alias Pepperidge seduces Banks assistant Abigail Sponder with pheromones

- After Earth: Blind extraterrestrial beings "see" their human victims using their fear pheromones.

See also

literature

- Richard P. Michael, RW Bonsall, M. Kutner: Volatile fatty acids, "copulins", in human vaginal secretions. In: Psychoneuroendocrinoloy. Volume 1, No. 2, 1975, pp. 153-163, doi: 10.1016 / 0306-4530 (75) 90007-4 .

- Warren ST Hays: Human pheromones: have they been demonstrated? In: Behavioral Ecological Sociobiology. Volume 54, No. 2, 2003, pp. 98-97, doi: 10.1007 / s00265-003-0613-4 .

- Mostafa Taymour, Ghada El Khouly, Ashraf Hassan: Pheromones in sex and reproduction: Do they have a role in humans? In: Journal of Advanced Research. Volume 3, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-9, doi: 10.1016 / j.jare.2011.03.003 .

- Tristram D. Wyatt: Pheromones and Animal Behavior: Communication by Smell and Taste. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-521-48526-6 .

- B. Thysen, WH Elliott, PA Katzman: Identification of estra-1,3,5 (10), 16-tetraen-3-ol (estratetraenol) from the urine of pregnant women (1). In: Steroids. 1968, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 73-87, doi: 10.1016 / S0039-128X (68) 80052-2 , PMID 4295975 .

- Karl Grammer, Bernhard Fink, Nick Neave: Human pheromones and sexual attraction. In: European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. Volume 118, No. 2, February 1, 2005, pp. 135-142.

- S. Jacob, DJ Hayreh, MK McClintock: Context-dependent effects of steroid chemosignals on human physiology and mood. In: Physiology & Behavior. 2001, Vol. 74, No. 1-2, pp. 15-27, doi: 10.1016 / S0031-9384 (01) 00537-6 , PMID 1156444.7

- J. Verhaeghe, R. Gheysen, P. Enzlin: Pheromones and their effect on women's mood and sexuality. In: Facts, views & vision in ObGyn. Volume 5, number 3, 2013, pp. 189-195, PMID 24753944 , PMC 3987372 (free full text) (review).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Karl Grammer, Bernhard Fink, Nick Heave: Human pheromones and sexual attraction . (English), In: European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. Volume 118, No. 2, 2005, pp. 135-142.

- ^ Peter Karlson, Martin Lüscher: Pheromones: a New Term for a Class of Biologically Active Substances. In: Nature . No. 183, 1959, pp. 55-56, doi: 10.1038 / 183055a0 .

- ^ GK Beauchamp, RL Doty, DG Moulton, RA Mugford: Response by Beauchamp et al., Letters to the editors, In defense of the term “pheromones”. In: Journal of Chemical Ecology. Volume 5, No. 2, March 1979, pp. 301-305.

- ↑ Roger A. Katz, HH Shorey, Gary K. Beauchamp and others. a .: In Defense of the term pheromones. In: Journal of Chemical Ecology. Volume 5, No. 2, March 1979, pp. 299-305, doi: 10.1007 / BF00988244 .

- ^ Department of Molecular Physiology, University of Heidelberg: Behavior of Hamsters. ( Memento of July 16, 2012 on the Internet Archive ) (authentication required).

- ^ Department of Sensory Physiology, University of Heidelberg: Pheromones in mice. ( Memento of November 2, 2005 on the Internet Archive ) (Authentication required).

- ↑ Bernd Schäfer: Natural substances in the chemical industry. 1st edition. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8274-1614-8 , pp. 118-119.

- ^ A b Sarah Roberts, Deborah Simpson, Stuart Armstrong a. a .: Darcin: a male pheromone that stimulates female memory and sexual attraction to an individual male's odor . In: BMC Biology . tape 8 , no. 1 , 2010, ISSN 1741-7007 , p. 75 , doi : 10.1186 / 1741-7007-8-75 ( biomedcentral.com [accessed June 4, 2010]).

- ↑ H. Lee, S. Finckbeiner, JS Yu et al. a .: Characterization of (E, E) -farnesol and its fatty acid esters from anal scent glands of nutria (Myocastor coypus) by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-infrared spectrometry . In: J Chromatogr A . tape 1165 , no. 1-2 , September 2007, pp. 136-43 , doi : 10.1016 / j.chroma.2007.06.041 , PMID 17709112 .

- ↑ M. Spehr, G. Gisselmann, A. Poplawski a. a .: Identification of a testicular odorant receptor mediating human sperm chemotaxis. In: Science. Volume 299, No. 5615, 2003, pp. 2054-2058. PMID 12663925 , doi: 10.1126 / science.1080376 .

- ↑ LB Voss Hall: Olfaction: attracting Both sperm and the nose. In: Curr. Biol. Vol. 14, No. 21, November 2004, pp. R918-R920. PMID 15530382 , doi: 10.1016 / j.cub.2004.10.013 (PDF)

- ↑ Vivienne Baillie Gerritsen: Love at first smell. In: Protein Spotlight. 2010 (PDF)

- ^ Martha McClintock: Menstrual synchrony and suppression. In: Nature. No. 229, 1971, pp. 244-245. PMID 4994256 .

- ↑ Martha McClintock, K. Stern: Regulation of ovulation by human pheromones. In: Nature. No. 392, 1998, pp. 177-179. PMID 9515961 .

- ↑ Do women's periods synchronize when they spend time together? A study carried out by a fertility app and Oxford University says not, but still the myth endures.

- ^ I. Savic: Brain response to putative pheromones in lesbian women. In: PNAS . Volume 103, No. 21, 2006, pp. 8269-8274. PMID 16705035 , doi: 10.1073 / pnas.0600331103 .

- ↑ T. Boehm, F. Zufall: MHC peptides and the sensory evaluation of genotype. In: Trends Neurosci. Volume 29, No. 2, 2006, pp. 100-107. PMID 16337283 (PDF)

- ↑ PS Santos, J.A. Schinemann, J. Gabardo, G. Bicalho: New evidence that the MHC influences odor perception in humans: a study with 58 Southern Brazilian students. In: Horm. Behav. Volume 47, No. 4, 2005, pp. 384-388.

- ↑ MF Bhutta: Sex and the nose: human pheromonal responses. In: Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Volume 100, No. 6, 2007, pp. 268-274, PMC 1885393 (free full text).

- ^ Warren ST Hays: Human pheromones: have they been demonstrated? In: Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. Volume 54, Number 2, July 2003, pp. 89-97, doi: 10.1007 / s00265-003-0613-4 .

- ↑ Claire Wyart et al. a .: Smelling a single component of male sweat alters levels of cortisol in women. In: J. Neurosci. Volume 27, No. 6, 2007, pp. 1261-1265. PMID 17287500 , doi: 10.1523 / JNEUROSCI.4430-06.2007 .

- ↑ a b c Richard P. Michael, RW Bonsall, M. Kutner: Volatile fatty acids, “copulins”, in human vaginal secretions. In: Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1975, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 153-163. PMID 1234654 .

- ↑ Hans-Rudolf Tinneberg, Michael Kirschbaum, F. Oehmke (eds.): Gießener Gynäkologische Furtherbildung 2003: 23rd further training course for doctors in gynecology and obstetrics. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 2013, ISBN 978-3-662-07492-3 , p. 151.

- ^ RP Michael, EB Keverne: Pheromones in the communication of sexual status in primates. In: Nature. No. 218, 1968, pp. 746-749.

- ^ A b R. P. Michael, EB Keverne, RW Bonsall: Pheromones: isolation of male sex attractants from a female primate. In: Science. No. 172, 1971, pp. 964-966. PMID 4995585 .

- ^ RF Curtis, JA Ballantine, EB Keverne u. a .: Identification of primate sexual pheromones and the properties of synthetic attractants. In: Nature. No. 232, 1971, pp. 396-398.

- ↑ AL Cerda-Molina, L. Hernández-López, CE de la O, R. Chavira-Ramírez, R. Mondragón-Ceballos: Changes in Men's Salivary Testosterone and Cortisol Levels, and in Sexual Desire after Smelling Female Axillary and Vulvar Scents. In: Frontiers in endocrinology. Volume 4, 2013, p. 159, doi: 10.3389 / fendo.2013.00159 . PMID 24194730 , PMC 3809382 (free full text).

- ↑ K. Grammer, A. Jütte: The war of fragrances: Importance of pheromones for human reproduction. In: Gynecological obstetric review. Volume 37, No. 3, 1997, pp. 150-153.

- ^ V. Prelog, L. Ruzicka: Studies on organ extracts. (5th part). About two musky smelling steroids made from pig test extracts. In: Helvetica Chimica Acta. Volume 27, 1944, p. 61.

- ^ V. Prelog, L. Ruzicka: Studies on organ extracts. (5th part). About two musky smelling steroids made from pig test extracts. In: Helvetica Chimica Acta. Volume 27, 1944, p. 66.

- ↑ Manhood does not have to harm the flesh . In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . March 3, 2010.

- ↑ Judith Amberg-Müller: Pheromones in Cosmetic Products - Influencing the opposite sex with the body's own human fragrances An overview of physiology and toxicology ( Memento of the original from August 22, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked . Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Volume 5, Federal Office of Public Health - CH, 2000, pp. 597–609.