musk

Musk (German since the 17th century; like Latin muscus from Greek μόσχος moschos and according to Walde and Hofmann via Old Persian musk from old Indian muskah , `` testicles '') is the dried, powdery and strongly smelling secretion from the hairy musk sac ( preputial gland between the navel and penis) from the male musk deer .

To obtain secretions, the musk deer had to be killed until the end of the 1950s; Today, musk farms are operated in China, where about 10 grams of secretion per musk deer are obtained annually by scraping the gland. However, the quality is much worse here and the amount is significantly lower. In addition, the deer are traumatized and can then also die. The reddish-brown, oily mass (the musk) becomes crumbly and dark brown after drying. The pouches, which weigh up to 50 grams, contain around half of the musk in wild animals. Today, industrially manufactured substitutes are used in the manufacture of perfumes and soaps . Musk contains components that are structurally similar to pheromones and are said to have an aphrodisiac effect.

Musky scent

As a component of perfumes, the scent of musk is said to combine an "animal" and a "radiantly sweet" scent note. The "animal element" gives people warmth and thus feelings of security and sexual stimulus. The fragrance should be used sparingly and below the limit of conscious perception. Musk notes are not only used as fragrances, but are also occasionally found as aromas in foods . So z. B. in Australia sold sweets with musk flavor.

Natural musk

The German chemist Heinrich Walbaum (1864–1946) was able to isolate the main component of musk in the form of white crystals in 1906. He named the connection Muscon , the structure was clarified by Lavoslav Ružicka in 1926 .

Natural muscon is made from musk that has been used as a perfume for centuries. It is an oily liquid that is found in nature as the enantiomer ( R ) - (-) - 3-methylcyclopentadecanone. Originally, only the secretion from a gland on the belly of the musk deer in front of the sexual organs was called "musk". Musk was already known in ancient times through the mediation of the Persians ; Musk deer lived on the eastern borders of their empire.

The term “musk” is also applied to glandular secretions from other animals and to vegetable juices that have a similar odor. Among the animals , musk ox , musk ram , muskrats , desmans and musk ducks secrete such "false musk"; in plants, these are for example the Gauklerblume , the Abelmoschus , Olearia argophylla (Australian Bisamholz) which amberboa moschata , the musk mallow , the Rosa moschata ( double varieties ) or the moschatel . Hypoestes moschata from Australia gives off a strong musk scent .

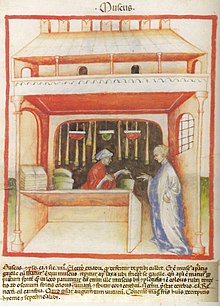

history

The European medical writers of antiquity, including Dioscurides , Pliny and Galen , did not mention musk. It was not until the Arab doctors reported about this extremely valuable drug, which came from a gazelle-like animal living in "India", ie in the Himalayas, which had "two long white teeth like two horns". In the 4th century, the Middle Persian name muschk also found its way into the West as muscus (as in Hieronymus and later in Circa instans ). According to the juice theory , the musk was classified as "warm and dry in the second degree". Up until the beginning of the 20th century, it was ascribed to have a generally invigorating and invigorating effect as well as strengthening nerves and relieving cramps.

Sources (selection)

Arab Middle Ages

- Avicenna , 10.-11. Century

- Constantine the African , 11th century

- Circa instans , 12th century

- Pseudo-Serapion , 13th century

- Abu Muhammad ibn al-Baitar , 13th century

Latin Middle Ages

- Konrad von Megenberg , 14th century

- Gart der Gesundheit , Mainz 1485

- Hortus sanitatis , Mainz 1491

- Hieronymus Brunschwig , Strasbourg 1512

17.-18. century

- Nicolas Lémery , 1699

- Johann Baptista du Halde , 1749

- William Cullen , 1781

19. – 20. century

- Theodor Husemann , 1883

- Hager's Handbook of Pharmaceutical Practice , 1920

Use in sports

Oral use of musk is part of Chinese folk medicine, it increases testosterone levels and is therefore considered doping. Researchers at the Cologne Anti-Doping Laboratory found this out rather by chance, who asked people about the source of elevated testosterone levels and then tested original musk with the help of the Cologne Zoo and checked the statements.

Artificial Musk Substitutes and Artificial Musk

Artificial substitutes

The artificial substitutes have a scent similar to musk. But they belong to other substance classes, i. H. these substances have a different molecular structure and usually do not occur naturally.

Nitro aromatics

In 1888, the chemist Albert Baur was the first to succeed in producing a musk fragrance substitute. The first substance he synthesized and sold, "Musc Baur", also known as "Tonquinol", was the starting point for a whole class of musk substitutes that belong to the nitro aromatics . Albert Baur brought three more nitro aromatics , also known as “ nitro musks ”, onto the market: the musk ketone , which is still used today, the musk xylene , which has been banned since 2014, and the musk ambrette. However, these artificial substitutes are not entirely harmless. The nitroaromatics musk ambrette, musk mosques and musk Tibetans were therefore banned in EU regulations in 1995 and 2000, respectively.

Polycyclic substitutes and their environmental compatibility

For cosmetics and the perfuming of detergents, instead of natural musk and instead of nitroaromatics, polycyclic musk substitutes are mainly used today. These are mostly mixtures of substances with the trade names Galaxolid ( HHCB ) and Tonalid, more rarely Celestolid and Pantolid.

Polycyclic musk substitutes (cf. Cashmeran ) are hardly soluble in water and have a low polarity. Due to these lipophilic properties, they accumulate in adipose tissue (bioaccumulation). Their use in cosmetic products is therefore controversial. Due to their difficult degradability, they are only partially removed from the wastewater by the wastewater treatment processes in municipal sewage treatment plants. Therefore, Galaxolid and Tonalid, subordinate also Celestolid and Pantolid, are detectable in water, sediments and suspended matter of all German rivers.

Artificial Muscon and Artificial Musk

Nowadays, muscon , the main fragrance of musk, and mixtures corresponding to musk are also produced synthetically for reasons of environmental and species protection. Similar to the nature-identical flavors in food, the disadvantages of foreign substances (such as nitroaromatics) can be avoided by using fragrance mixtures that are as nature-identical as possible. However, this does little to detract from the popularity of the original animal musk, especially since it is also important in traditional Chinese medicine and no synthetic substitute is used there. Synthetically produced muscon is a racemate , i.e. it consists of a 1: 1 mixture of ( R ) - (-) - 3-methylcyclopentadecanone and ( S ) - (+) - 3-methylcyclopentadecanone.

composition

Components of musk are:

- Muscon , C 16 H 30 O, main fragrance of musk, content 0.5 to 2%

- Muscopyridine , C 15 H 25 N

- 2,6-nonamethylene pyridine , C 14 H 21 N

- 2,6-Decamethylenpyridin , C 15 H 23 N

- 3-methylcyclotridecanone , C 14 H 26 O

- Cyclotetradecanone , C 14 H 26 O

- 5- cis -cyclotetradecenone , C 14 H 24 O

- 5- cis -cyclopentadecenone , C 15 H 26 O

- 14-methyl-5- cis -cyclopentadecenone , C 16 H 28 O

- Muscol , C 16 H 32 O

Literature and media

- Lukas Schröck : Historia moschi. Ad normam academiæ naturæ curiosorum conscripta . Göbel, Augsburg 1682.

- E. Th. Guericke: De moscho. Erfurt 1776.

- Tilman Achtnich: The Smell of Death. Musk - from the most expensive fragrance in the world . Südwestrundfunk , 2001 (documentary film).

- DJ Rowe: Chemistry and technology of flavors and fragrances . Blackwell, Oxford et al. 2005, pp. 143–165 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Bernd Schäfer: Natural substances in the chemical industry. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8274-1614-8 , pp. 118-119.

- ↑ Alois Walde : Latin etymological dictionary. 3rd edition, obtained from Johann Baptist Hofmann , I – III, Heidelberg 1938–1965, II, p. 134.

- ↑ Ruth Spranger: On the use of musk (musk) and its substitutes in medieval medicine, in particular in the 'Breslau Pharmacopoeia'. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 17, 1998, pp. 181-186, here: pp. 181 f.

- ↑ Musk Deere on Tibet Nature Environmental Conservation Network, accessed June 7, 2018.

- ↑ Anya H. King: Scent from the Garden of Paradise. Brill, 2017, ISBN 978-90-04-33624-7 , p. 21.

- ↑ Fred Winter: Handbook of the entire perfume and cosmetics. Springer, 1927, ISBN 978-3-662-37394-1 (reprint), p. 88.

- ↑ Johannes Friedrich Diehl: Chemistry in food residues, impurities, ingredients and additives . John Wiley & Sons, 2012, ISBN 978-3-527-66084-1 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Musk - King of Fragrances. In: Gesundheit.de. July 4, 2017, accessed March 5, 2018 .

- ↑ Lifesaver Musk - Candy Blog. Retrieved March 5, 2018 .

- ↑ The Lone Baker - Journal - Musk Sticks. Accessed March 5, 2018 .

- ^ H. Walbaum: The natural musk aroma. In: Journal for Practical Chemistry. 73, 1906, p. 488, doi: 10.1002 / prac.19060730132 .

- ↑ L. Ruzicka: To the knowledge of the carbon ring VII. About the constitution of the Muscon. In: Helvetica Chimica Acta. 9, 1926, p. 715, doi: 10.1002 / hlca.19260090197 .

- ↑ Georg Schwedt: Beguiling fragrances, sensual aromas . John Wiley & Sons, 2012, ISBN 978-3-527-64118-5 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ Goutam Brahmachari: Chemistry and Pharmacology of Naturally Occurring Bioactive Compounds . CRC Press, 2013, ISBN 978-1-4398-9167-4 , pp. 16 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Ruth Spranger: On the use of musk (musk) and its substitutes in medieval medicine, in particular in the 'Breslau Pharmacopoeia'. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 17, 1998, pp. 181-186.

- ^ Eduard Martiny : Natural history of animals important for medicine ... Leske, 1847, p. 75, restricted preview in the Google book search.

- ↑ The Victorian Naturalist. Volume 8, Walker, May, 1892, p. 66.

- ↑ = Ibn Butlan . 11th century Taqwim es-sihha . Tacuinum sanitatis in medicina. Print in Latin translation. Johann Schott. Strasbourg 1531, p. 111, (digitized version) .

- ↑ Martin-Dietrich Glessgen: The falcon medicine of the Moamin in the mirror of their volgarizzamenti. Studies on Romania Arabica. Volume I: Edition of the Neapolitan and the Tuscan version with philological commentary. Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 1996 (= Journal for Romance Philology; Supplements. Volume 269), ISBN 3-484-52269-0 , pp. 882–884.

- ↑ Konrad Goehl : Observations and additions to the 'Circa instans'. In: Medical historical messages. Journal for the history of science and specialist prose research. Volume 34, 2015 (2016), pp. 69-77, here: p. 70.

- ↑ Avicenna , November 10-11. Century canon of medicine . Revision by Andrea Alpago (1450–1521). Basel 1556. Book II. Simple Medicines, Chapter 460: De Muscho (digitized version ) .

- ↑ Constantine the African . 11th century Liber des gradibus simplicium = translation of Liber des gradibus simplicium of Ibn al-Jazzar . 10th century printing. Opera . Basel 1536, p. 354, (digitized version) .

- ↑ Circa instans , 12th century print. Venice 1497, sheet 203v (digitized version ) .

- ^ Pseudo-Serapion , 13th century print. Venice 1497, sheet 123r (digitized version )

- ↑ Abu Muhammad ibn al-Baitar , 13th century. Kitāb al-jāmiʿ li-mufradāt al-adwiya wa al-aghdhiya - Large compilation of the powers of the known simple healing foods and foods. Translation. Joseph Sontheimer under the title Large compilation on the powers of the well-known simple healing and food. Hallberger, Stuttgart Volume II 1842, pp. 513-516, (digitized version ) .

- ↑ Konrad von Megenberg , 14th century. Main source: Thomas von Cantimpré , Liber de natura rerum . Output. Franz Pfeiffer . Konrad von Megenberg. Book of nature. Aue, Stuttgart 1861, p. 151, (digitized version) .

- ↑ Gart der Gesundheit . Peter Schöffer , Mainz 1485, Chapter 272, (digitized version) .

- ^ Hortus sanitatis . Jacobus Meydenbach, Mainz 1491, De animalibus, Chapter 100 (digitized version) .

- ↑ Hieronymus Brunschwig . Liber de arte distillandi de compositis. Johann Grüninger, Strasbourg 1512, p. 80r (digitized version ) .

- ↑ Nicolas Lémery : Dictionnaire universel des drogues simples, contenant leurs noms, origines, choix, principes, vertus, étymologies, et ce qu'il ya de particulier dans les animaux, dans les végétaux et dans les minéraux. Laurent d'Houry, Paris, 1699 German translation: Complete Lexicon of Materials. Complete material lexicon. Initially designed in French, but now after the third edition, enlarged by a large one [...] translated into High German / by Christoph Friedrich Richtern, [...]. Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Braun, 1721, pp. 744–746 (digitized version ) .

- ^ Johann Baptista du Halde . Detailed description of the Chinese Empire and the great tartarey. 3rd part. Johann Christian Koppe, Rostock 1749, pp. 517-519: From the Musc or Bisam (digitized version )

- ↑ William Cullen . Lectures on the materia medica. German. JP Ebeling, Weygand, Leipzig 1781, p. 429, (digitized version) .

- ^ Theodor Husemann .: Handbook of the entire drug theory. Springer, Berlin 1873-1875, Springer, 2nd edition, Berlin 1883, Volume II, pp. 930-933 (digitized version ) 3rd edition, Springer, Berlin 1892, pp. 490-492 (digitized version ) .

- ^ Hager's Handbook of Pharmaceutical Practice . 9. Unchanged print, Julius Springer, Berlin 1920, pp. 406–409, (digitized version ) .

- ↑ M. Thevis, W. Schänzer, H. Geyer u. a .: Traditional Chinese medicine and sports drug testing: identification of natural steroid administration in doping control urine samples resulting from musk (pod) extracts. In: Br. J. Sports Med. 47 (2), 2013, pp. 109-114, cf. Arnd Krüger : Natural Medicine. In: competitive sport (magazine) . 42, 5, 2012, p. 31. (PDF) .

- ↑ a b c Wolfgang Legrum: Fragrances, between stench and fragrance: Occurrence, properties and use of fragrances and their mixtures . 2., revised. and exp. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-658-07309-1 , p. 166–167 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-658-07310-7 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Artificial musk fragrances (PDF), from Greenpeace, accessed on June 7, 2018.

- ↑ Peter Brandt: Reports on Food Safety 2007 Food Monitoring . Springer-Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-7643-8913-0 , pp. 76 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Günter Fred Fuhrmann: Toxicology for Natural Scientists Introduction to Theoretical and Special Toxicology . Springer Science & Business Media, 2006, ISBN 3-8351-0024-6 , p. 331 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ a b Umweltbundesamt: Fact Sheet Polymoschusverbindungen ( Memento from November 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 35 kB).