Ideal of beauty

An ideal of beauty is a contemporary conception of beauty within a culture . Usually the term refers to the appearance of the body and face. Ideas of beauty related to clothing, jewelry or hairstyle are called fashion .

Ideals of beauty exist for both sexes, but played and still play a greater role for women as well as for their perception of the outside world than for men. Male and female ideals of beauty change over time, refer to each other and at least partially align with each other. However, the opposite is also the case: the strong emphasis on gender differences. The ideal was (and is) often precisely what is considered particularly and typically male or female.

Universal ideal of beauty

At first glance it looks as if ideals of beauty are limitlessly changeable. For example, the body's fullness (or weight), which is regarded as ideal in each case, fluctuates considerably in a comparison of cultures and eras. There were epochs in Europe - and in other cultures - where " baroque " and fuller forms were (or are) modern, while at other times there is a rather slender ideal. Even ideal measurements fluctuate: if a waist circumference of 60 is considered ideal for models today, in the times of the wasp waist it could not be more than 54 cm. For centuries, even millennia, and not only in Europe , but z. For example, in Japan , China and other Asian countries, flawless, soft white skin was considered one of the most important characteristics of a beautiful woman - but this changed relatively suddenly in the 20th century, at least in the West, when, starting with America, among others. a. a sporty way of life became modern, the sun-tanned skin - despite the increased risk of premature skin aging and skin cancer - declared a sign of "health", and of course a much sought-after 'proof' that one can enjoy the luxury of sunbathing and / or a vacation in the south can afford. From the examples given, one could theoretically conclude that ideals of beauty develop in any way whatsoever.

On the other hand, the research on attractiveness points out that the respective ideals of beauty, despite all cultural variability, also have commonalities. According to their findings, human beauty is based at least in part on definable factors that are subject to a relative consensus between individuals and cultures and are biologically anchored - such as the flawlessness of the skin. Ideals of beauty therefore contain a supra-individual and supra-cultural “hard core” - which could explain the fact that some beauty icons of past centuries and millennia, such as the Venus of Milo or Raphael's Madonnas, are also perceived as beautiful by today's people. Recent research suggests that there is a distinct genetic component to being beautiful. The evolutionary biological explanation for ideals of beauty is that perceived beauty correlates with evolutionarily advantageous properties. In experiments and surveys, it was found that in all cultures women with a culture-specific ideal waist-to-hip ratio are viewed by the test subjects as beautiful, for example in African regions with insufficient food, obesity with a markedly large hip and buttock circumference. Symmetry is perceived as beautiful and at the same time is a medical indicator of health. There is also evidence that the golden ratio plays a role in the aesthetic evaluation of a face. A vertical distance between the eyes and mouth of 36% of the face length and a horizontal distance between the eyes of 46% of the face width are ideal. These proportions correspond to the average face, which, like symmetry, also signals health. Some scientists therefore consider the concept of beauty as a cultural construct to be a myth.

Ideals of beauty, power and abuse

"Who wants to be beautiful must suffer."

People have always used a wide variety of means to meet the prevailing ideas of beauty, be it with the help of clothing and jewelry or through direct changes to the body.

Many peoples are known to have drastic, drastic body modification practices such as filing teeth, the apparent lengthening of the neck with brass rings (the padaung ), with which the shoulder blades are de facto lowered, the insertion of discs in the ears or lips - so-called " plate lips " - or the application of tattoos or so-called 'jewelry' scars on the skin.

In the European context, this also includes the traditionally customary piercing of ears for earrings for girls and women, or the centuries-old wearing of tightly laced corsets from childhood, which can lead to deformities of the ribs and the chest and stress the function of the internal organs (especially liver , kidneys , stomach , lungs ).

However, these changes not only serve to increase the attractiveness in an aesthetic or sexual sense. They often convey a much broader social message, such as belonging to a class, a clan or a certain initiation year .

In the Chinese custom of tying the feet ( lotus foot ), the feet of young girls in ancient China were crippled by extreme binding and bone breaking in favor of the ideal of beauty of a tiny foot - an ideal that basically and in a less extreme form also exists in Europe (e). The Chinese custom is said to go back to a mistress of Emperor Li Houzhu , the last emperor of the southern Tang dynasty (around 975). This dancer bandaged her feet in order to be able to perform special performances on the golden stage in the shape of a lotus blossom , which the emperor had built for her. Women with lotus feet could only walk short distances with difficulty and pain. They were handcuffed to the house. The lotus foot and the typical streaking, actually helpless gait were considered to be an important beauty feature in China for centuries, and there were men to whom the tiny crippled feet of the woman were more important than the face.

A clear separation between “ social ” and “aesthetic” changes in the body is usually not possible. Ideals of beauty always reflect the power relationships that prevail in the respective society. For example, tanned skin, which has always been a sign of underprivileged, became a beauty attribute in the 1960s when the better-off discovered the Mediterranean as a holiday destination.

Also the artificial straightening of the hair widespread among many modern African-Americans , the spread of surgically "westernized" eyelids in many Asian countries, the sunbathing of people from Europe and North America, the increasing frequency of cosmetic surgeries or other measures since the end of the 20th century Injecting Botox or silicone into the face show the important role socio-economic factors play in the perception of attractiveness.

People who do not conform to the prevailing ideal of beauty can suffer disadvantages in the form of discrimination, which also depends on other factors such as gender. The term lookism has recently been used for discrimination based on external appearance .

Ideals of beauty and body weight

For comparison: today the ideal is waist 60 cm & chest 90 cm. The ideal difference used to be greater because of the commonly used corset .

The ideal of slimness that emerged from the western fashion industry in the second half of the 20th century, as it is propagated with the help of large, over-slim mannequins and models, who are often underweight and often artificially starve themselves down to size 34 or 36, has in historical and intercultural comparison rarity. Feminine attractiveness has been and is associated with a well-rounded body and full hips in most societies. For Europe, however, it must be noted that laced waists were fashionable as early as the 15th and 16th centuries, which increased from around 1640 to around 1915 to the ideal of the wasp waist and the so-called 'hourglass shape', which only with help of corsets and with a not inconsiderable health risk.

A modern ethnographic study showed that in almost half of the 62 cultures examined, fat women are considered attractive, a third prefer medium weight classes and only 20% prefer thin figures. With the advance of globalization , the western ideal of slimness is spreading more and more worldwide. On the other hand, there have never been so many overweight people in the US and Europe as in the early 21st century.

The great differences in body fullness, which is considered ideal, are sometimes explained by the different food supply: where the supply situation is uncertain, fat becomes a status symbol . Conversely, in times of abundance, a slim body is a coveted luxury good. According to ethnological studies, however, other factors also play a role, including the position of women: the more power women have, the more likely their men will prefer slim partners. In modern western societies, obesity is also often associated with negative attributes such as a lack of discipline, effeminacy or illness. The climate also seems to influence the ideal of the body: the warmer the area, the more likely a slim physique is considered attractive. However, over half of the intercultural differences in the body ideal cannot be explained by definable environmental influences and are apparently simply a question of fashion .

In historical retrospect, the fashion ideals of the respective epochs seem to fluctuate back and forth between the two poles of female attractiveness - "femininity" and "youthfulness". While certain epochs, such as the Middle Ages , preferred slim, youthful forms, in others the "full woman" was attractive. Even the ideas of beauty related to the male body seem to be subject to the polarity of maturity and youthfulness - man and youth, Hercules and Adonis . Compared with the high fluctuations in the female figure ideals, the image of the ideal male figure is much more stable.

Change in occidental ideas of beauty

Early history

The so-called Venus von Willendorf is often used as evidence that obesity was part of the ideal of beauty in early European history. The Paleolithic female figure, however, is not likely to be an idol of beauty, but rather an idol of fertility.

Egypt

The ancient Egyptian culture was already highly refined, and personal hygiene played a major role. Fragrant ointments , oils and cosmetics were used. There was artfully crafted jewelry and the finest transparent fabrics, some of which were placed in pleated folds and let the body shapes shine through, as well as precious wigs and other headgear. The fashions hardly changed. The objects from the dynasty of Pharaoh Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti , whose name means: "The beautiful has come", have a particularly aesthetic effect . Her famous bust looks amazingly lifelike and almost modern and allows insights into the make-up with eyelid lines and 'red lips' that was common at the time. The facial features are harmonious, the neck noticeably long and graceful. A likewise preserved (ideal?) Statuette of Nefertiti shows very pronounced feminine curves with rather moderate breasts.

Alabaster statuette of Chephren , 4th Dynasty, ca.2558-2532 before. BC ( Cairo ). The builder of the second pyramid of Giza is depicted with a well-formed body and wearing the classic Egyptian loincloth and an artificial royal beard .

Examples of ancient Egyptian long hair styles (probably wigs), funerary figures of the Maya and their husband Merit, 18th Dynasty, between 1325 and 1310 BC (RMO Leiden )

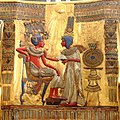

Tutankhamun and his wife Ankhesenamun , 18th Dynasty, ca.1330 BC

Greek and Roman antiquity

In the Greek classical period , the ideal body had harmonious proportions and should not be too fat or too thin. Representations of the Greek goddess of beauty and love Aphrodite can be considered the embodiment of a classical ideal. Statues such as the Venus de Milo (the Roman equivalent of Aphrodite) show that ideal female figures had rather small but firm breasts and a well-shaped pelvis. There were different types of ideal male figures: on the one hand the young athlete, as embodied in the extreme by Hercules or by the god of war Ares / Mars ; but also somewhat ethereal, fine types, as depicted in portraits of Apollo or the youthful Ganymede . As evidenced by its statues and frescoes, the ideal of beauty in Roman antiquity was very similar to that of its Greek predecessor. Obesity, however, had no negative connotation; on the contrary, it was seen as a sign of wealth.

Hair and beard costumes changed depending on the fashion, but wavy and curly hair were popular in both Greece and Roman antiquity. With the Greeks it was often artistically styled, women mostly pinned their hair up. Unkempt, straight hair was a sign of grief in Greece. For the Romans, hairdos were initially a little simpler during the republic , later in the imperial era , sometimes very complicated hairdos and also golden-blonde or red-colored hair (for women) became modern.

The Aphrodite of Knidos , between 350 and 340 BC Chr.

The Venus de Milo , late 2nd century BC Chr.

Complicated pomp hairstyle of a beautiful Roman woman, Flavian era , end of the 1st century. AD ( Capitoline Museums , Rome)

Ideal portrait of Alexander the Great , 3rd cent. v. Chr., NY Carlsberg Glyptothek, Copenhagen

middle Ages

The early and high Middle Ages were strongly influenced by the spiritual ideals of Christianity , and depictions of naked people are rarely found. Both Romanesque and Gothic art were relatively stylized and human figures were not yet shown anatomically completely correct - this makes more precise assessments of physical ideals difficult. For centuries, the fashion for both sexes consisted of long robes that were relatively comfortable and loose, and largely obscured the body shapes. But as far as it can be seen, the medieval ideal of beauty was a natural slenderness for both sexes. It was not until the late Middle Ages (14th – 15th centuries) that relatively realistic representations and the first natural portraits emerged, which enable a more precise assessment, although the art of the late Gothic period also reached a high point of stylization. The invention of buttons now made tight-fitting clothing possible. The ideal female beauty of the late Middle Ages was girlishly slim with slightly rounded shoulders and small, firm breasts. If the Madonnas and other figures of the highly stylized Gothic art are to be believed, an S-line seems to have been fashionable for women, especially in the 14th and 15th centuries: despite a very narrow, high waist and narrow hips, the belly should have been be conspicuously rounded to the front, the back tends to be arched. This is sometimes interpreted as a sign of pregnancy by today's viewers, but had nothing to do with it. Rather, a bulging belly was in some cases a center of erotic attention until the early 17th century. Medieval female beauty had white skin - simply because women were usually at home, and the color white symbolized purity , chastity and virginity - with pink cheeks and a rather small, red mouth. One can only speculate about a preference for hair colors, especially since only young unmarried girls wore their hair in an openly visible manner. After the marriage (which often took place before the age of 20) the hair was covered with veils , scarves and / or hoods . Young unmarried women wore their hair wavy, braided or pinned up. Also in men was z. Sometimes chin- or shoulder-length hair is modern.

In the 15th century, the ideal became extremely slim and elegant for women and men, which was also emphasized by fashion through narrow waists, tightly knotted robes and for men through long, tight trousers, which required well-shaped legs especially from the young man (the abdomen the woman couldn't be seen under the wide skirt). One of the most striking ideals of feminine beauty in both Burgundian fashion and early Renaissance Italy was the high forehead: one shaved or plucked one's hair at the hairline. The hair was artfully pinned up and hidden in the Burgundian sphere of influence under often high and pointed hoods ( hennin ), which emphasized the overall high, slim line. The elegant Burgundian (or French) man wore his hair very short in a kind of 'pot cut', shaved on the sides over the ears and partly on the neck.

In the late Gothic and early Renaissance (15th century), long, curly hair was an attribute of the handsome, young man, just like fair skin - but less as a sign of a noble, idle way of life than in reference to the angelic figures in the religious Art. The ideal male figure had broad, very upright shoulders (which were often stuffed and visually broadened); a swollen chest; a very narrow waist that was laced (!) and accentuated the wider shoulders even more clearly; narrow hips, long, slender legs and large feet (which are optically lengthened by the footwear).

Engagement scene with festively dressed aristocrats and women in typically stylized Gothic posture, around 1400, detail from the “April” picture in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (f.4)

Rogier van der Weyden : Lady with a Winged Hood , ca.1440

Fashion of the shaved high forehead in the 15th century:

Portrait of a young girl by Peter Christ , around 1470The high forehead is also modern in the early Italian Renaissance, along with 'golden' hair.

Piero di Cosimo : Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci , ca.1480Rogier van der Weyden: Portrait of Charles the Bold , 1460

Two ephepic youths with long hair in Pinturicchios : Enea Silvio Piccolomini's coronation as a poet by Friedrich III. , Libreria Piccolomini , Siena, approx. 1502–1507

Renaissance

As early as the early Renaissance (15th century), a change in taste was heralded in Italy, which was strongly influenced by antiquity and by an interest in ancient Greek and Roman works of art and statues that began at this time. The now emerging ideal of beauty for both women and men is anatomically more coherent than in Gothic and above all corresponds to ancient ideals - at least in art , apart from individual modifications and ideals, this remains so well into the 19th century.

Also in the fashion world of the High Renaissance (approx. 1500 / 1510–1560) the relatively ethereal-slim ideal of the late Gothic and early Renaissance disappears for both sexes, people now love somewhat stronger figures. The ideal female figure of the High Renaissance tends to be a bit fuller (but not fat), but only has small to moderate, high-seated breasts. Small signs of well-being on the face, such as a very slight double chin, are definitely appreciated.

Never before was blonde , golden or reddish blonde hair so fashionable as it was during the Italian Renaissance (15th - 16th centuries), and never (since ancient times) was hair coloring so common. In order to meet the ideal, the (Italian) woman from Stand uses all sorts of tinctures, exposes her hair to the sun for days and also braids white and yellow silk into her hair. Since the skin should be snow-white at the same time, the hair was spread over a wide-brimmed hat during such sunbathing in order to carefully protect the face and décolleté from burns and tanning. The cheeks should be slightly red, the mouth neither too small nor too big and cherry red. One prefers to have dark brown eyes. The high Renaissance man (first half of the 16th century) is strong and muscular - wide shoulder pads and puffed sleeves optically support this tendency. He also wears a (full) beard and generally short hair (with exceptions mostly in young men). The male renaissance fashion with tight-fitting trousers also makes certain demands on beautiful legs.

Titian : Venus de Urbino , ca.1538

Leonardo da Vinci : La Belle Ferronière , approx. 1495–1499

In the middle of the century, Diane de Poitiers , the famous mistress of Henry II of France, is celebrated for her fabled beauty. The blonde Diane was twenty years older than her lover, but looked much younger, and tried her dazzling looks and 'eternal youth' through rigorous measures such as early morning horseback rides, daily baths, diets, and even the regular intake of gold (! ) in liquid form ( aurum potabile ). In the long run, however, the latter led to poisoning, which has now been scientifically proven: In a scientific analysis of one of her hairs in 2008–2009, gold levels were found to be 500 times higher than normal, as well as increased levels of mercury. She also became a muse of French art at the Fontainebleau school . This belongs to the so-called mannerism , which represented an ideal of slender bodies with overlong limbs (neck, arms and legs) (see also: Bartholomäus Spranger , Hans von Aachen ).

During the time of the Counter-Reformation and Spanish fashion (approx. 1550–1610 / 20), however, both sexes actually relied more on tall, slim silhouettes - despite padded and stuffed sleeves, trousers and bellies. Women even wear high chopins (a kind of Kothurn ) under their long skirts to look taller and slimmer. A tightly laced bodice ensures a straight posture, with the bosom flattened. The elegant gentleman in the late 16th century has short hair and often a gracefully trimmed beard (so-called Henri IV beard, or a combination of mustache and chin beard ) - because of the modern high-necked ruff , an overly long beard would be counterproductive. Beautiful men's legs are more in demand than ever and are put on display.

Anonymous or Juan Pantoja de la Cruz (?): Don Juan d'Austria , around 1570.

El Greco : Lady with a Lily in Her Hair , approx. 1590–1600. The beautiful Spanish woman has something Madonna-like about it , and the white lily also symbolizes purity.

Baroque and Rococo

According to the general opinion, lush forms were very popular with women in the early baroque period; fashion at the time of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) was very much in favor of a fuller build for both sexes, as large, softly draped amounts of fabric and high waists were now fashionable (even with armor!) that could hide or even simulate a tendency to obesity. The name “ Rubens figure ” goes back to the Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens , who is famous for his depictions of strongly built women with lush, exuberant curves ; in later times the so-called " baroque forms" also became proverbial.

But there is much to suggest that such expansive and powerful female figures were more of an individual ideal - or one that applied above all to Flanders and the Netherlands - and in no way could be considered a generally accepted ideal of beauty, since other painters of the time, such as Guido Reni , Domenichino , Poussin , van Dyck , Peter Lely and others a., painted significantly slimmer, if not 'skinny' women. The fashion stitches by Wenzel Hollar also show rather 'normally' slim women, and not Rubens figures. From at least 1660 - that is, from the high baroque period - the elegant French fashion under Louis XIV also began to prefer very narrow waists, which in reality could not be reconciled with excessively large body; the silhouette was now actually quite slim and tall, and the skirt was a bit puffy at the hips, but not particularly wide overall. However, at the same time the breasts should be well-formed (but not too big) and the shoulders and arms should be round and soft - visible shoulder bones were classified as 'lean' and were not desired. In general, great importance was attached to the beauty of the neck, décolleté, arms and hands, as these were largely uncovered and constantly seen in fashion between approx. 1630 and 1790.

From the middle of the 17th century, for almost three centuries - with the exception of a few decades after the French Revolution and at the beginning of the 19th century (so-called Directoire fashion ) - the 'hourglass shape' became the symbol of the ideal femininity in this Extreme form was only possible with the help of tightly laced corsets. In contrast to women and other epochs (Gothic / early Renaissance, 19th century), the baroque gentleman was allowed to have a little stomach, but beautiful legs and especially calves were still a trump card due to the knee breeches with silk stockings, and were helped dainty shoes with buckles or bows and high heels are also particularly advantageous.

In the 17th century there were several collections of portraits of beautiful women, in which the ideals of the time were presented, such as the gallery of beautiful ladies-in-waiting of Louis XIV in Versailles , which also included portraits of his mistress Madame de Montespan . The so-called "Windsor Beauties" is a similar series of portraits of English court ladies, which the painter Peter Lely carried out in the 1660s for the Duchess of York Anne Hyde . Cardinal Flavio Chigi had a gallery of Roman beauties ( Stanza delle Belle ) set up in his family seat in Ariccia - among those portrayed were Maria Mancini and her sister Ortensia , two former mistresses of Louis XIV; Maria was meanwhile also the beautiful cardinal's own lover. Even the well-known bon vivant and aesthetic spirit Roger de Bussy-Rabutin surrounded himself in his exile at Bussy-Rabutin Castle with a whole gallery of portraits of beautiful women from his aristocratic acquaintance. In all examples, however, it was always and exclusively about pictures of noble ladies from a courtly circle, it was not only about ideal beauty, but also about the social status and refinement of those concerned. It is also noticeable that no galleries of 'beautiful' men are known. B. the aforementioned Bussy-Rabutin in his castle long galleries of statesmen, generals and kings of France. So men were valued for other qualities such as strength, power, intelligence, they didn't necessarily have to be beautiful. Intelligence and esprit have been part of the beautiful woman's repertoire since the Renaissance at the latest.

Rubens: George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham , 1625. The English duke and favorite Charles I was recognized as one of the most beautiful men of his time.

Wenzel Hollar : Nobleman who bows ( The bowing gentleman ), ca.1630

Wenzel Hollar: English lady in winter habit with muff and mask, around 1630. The mask was supposed to protect the skin against the cold and sun.

Barbara Villiers was the most famous mistress of Charles II of England. Portrait by Peter Lely, 1660s.

Jane Needham, married Mrs. Myddleton, was described by John Evelyn as "famous and indeed incomparable beauty" but refused to be the mistress of Charles II. This portrait belongs to the series of "Windsor Beauties" by Peter Lely, approx. 1663-1665.

As in the centuries (or millennia) before, white skin was fashionable throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, and was sometimes emphasized with the help of make-up - especially the long-known and not harmless white lead - and powder . In the middle of the 17th century, women not only protected their skin against the sun with wide-brimmed hats, but also with masks, which were also supposed to help against other weather influences, such as winter cold; there were also parasols, which were introduced to the French court by Maria de Medici around 1600, and which were occasionally carried by pages. In the early baroque era, dark hair was considered beautiful for women, even blondes colored their hair darker with a black powder. In the early baroque era, men often wore twisted mustaches and goatees, which gradually became smaller until around 1650/1660 only a small, thin mustache remained, which also disappeared around 1680. From then on, the clean-shaven face was a must for the man for over 100 years.

In the baroque era, people loved long, curly hair, both for women and men. Since this fashion became more and more extreme with men and was by no means unproblematic (because of the tendency to baldness ), the allong wig appeared under Louis XIV around 1670 , which simulated an exuberant and long curls. From the early 18th century, wigs were powdered white, but after the death of Louis XIV (1715) they gradually became smaller until only the typical small rococo hairstyle with curls pinned to the side and hair gathered at the back remained. Women too powdered their hair white from the 18th century onwards, and in the late baroque era powdered wigs appeared, which were initially small and grew in size from around 1765 - up to enormous dimensions around 1780.

The beauty effort was immense for men and women in the late 17th and 18th centuries, but it took on extreme features for women in the Rococo, when hoop skirts ( panier ) also became modern, which made the laced waist look tiny. In addition, it was common, especially in the French aristocracy of the 18th century, to put on heavy make-up and put on cosmetic pads ( mouches ): it is said that women put on so much make-up, powder and rouge for a ball that their own husband did not recognized. Overall, the ideal of the late baroque and rococo (approx. 1720–1790) can be described with a certain right as doll-like and compared with the figures of Meissen porcelain .

Hyacinthe Rigaud : Portrait of Gaspard Rigaud , approx. 1691. The elegant gentleman in the era of Louis XIV wears a large Allonge wig .

Maurice Quentin de La Tour : Self-portrait , around 1750. More than 50 years later, the painter wears a typical powdered rococo wig with a bow.

Joshua Reynolds: Augustus Keppel , 1749. But even in the Rococo it is sometimes possible without a wig.

Philippe Vignon: Mademoiselle de Blois and Mademoiselle de Nantes (daughters of Louis XIV and Madame de Montespan ), around 1691

François Boucher : Madame de Pompadour , 1756. The maitresse and friend of Louis XV. was considered one of the most beautiful and adorable women in the world.

Thomas Gainsborough : Lady in Blue , around 1780.

19th century

After 1790, i.e. from the French Revolution, and in the early 19th century, people orientated themselves strongly towards Greek and Roman antiquity, which, however, had already been followed in the world of art. But now women's fashion itself has become Greek, and the appearance of women in particular has become more natural than it has been for centuries. Wigs and even the corset went out of style, the waist slipped up, the clothes became narrow. However, precisely because of its naturalness (!), The ideal of beauty was still a slender and well-formed body, which should not, however, be lean, with 'well-formed' shoulders and breasts, and still white skin. In historically documented times (and in Europe), women had a (relative) short hairstyle for the first time ever, with curls if possible. In addition, however, long hair was still modern, which was pinned up into Greek-looking hairstyles and buns. The wig also disappeared from men and around 1790 the so-called "Titus head" appeared, based on the ancient model and also with curly hair.

Much time was still devoted to hairstyles in the 19th century, especially among women. At the time of the Restoration and Biedermeier period around 1820 to 1850, extremely complicated hairstyles with side curls and pinned up hair were modern, which tended to be based on the Baroque of the 17th century, as well as corsets and hoop skirts (this time as crinoline ) - i.e. the exaggerated female hourglass- Figure - came back into fashion in a slightly different shape. Until well into the 20th century, white skin was protected from sun damage by broad hats and delicate parasols . In contrast to the Rococo, make-up was considered morally questionable, which was only to change again in the 1920s. Light and pastel colors, and especially white, underlined the " pure " femininity in the truest sense of the word .

From the 19th century there are known some alarming cases of extreme slimness: for example, the case of a 23-year-old woman in Parisian society, who was admired for her narrow waist when it became known that she was only two, caused horror She died days later because her liver was pierced by three ribs (!) Through the tight lacing of the corset . The Austrian Empress "Sissi" also practiced a true cult of beauty that took many hours a day and included both rigid diets (some with ox blood) and excessive exercise, which was completely unusual, especially for a woman of her time. Just styling and braiding her knee-length hair into a very individual, elaborate hairstyle took 2 hours. She was considered one of the most beautiful women of her time and was very much admired, but her extreme - in truth anorexic - 'slimness' and sportiness also met with alienation and incomprehension.

However, Empress Sissi also admired the beauty of other women and created a whole collection of pictures of beautiful women, including her sister "Néné". Her uncle Ludwig I of Bavaria was such a great admirer of female beauty that he created a now famous gallery of beauties for which he had the 36 most beautiful women he could find painted - although he didn't care whether it was was a simple peasant girl, a citizen or a woman of the high nobility. The selection also did not follow a completely one-sided ideal, but comprised very different types of women, both blue-eyed blondes and dark-eyed brunettes , and even the red-haired Wilhelmine Sulzer; and there were also foreign women from England, Italy, Greece and Ireland among them, and also a lady of Jewish descent ( Nanette Kaulla ). It was important to the king, however, that the women depicted lived an “impeccable way of life”. For him, beauty was inseparable from virtue, and he named the first Auguste Strobl, for example, “the most beautiful, the most virtuous, who was ever born”.

In the 19th century, the difference between the sexes was particularly emphasized by the fact that it was increasingly considered unmanly for men to dress up too much. In contrast to women, men’s fashion became more practical, simpler and darker after the revolution - an influence of the bourgeoisie that was less colorful than the nobility even before the revolution: “Men seemed to have renounced the right to beauty and, above all, to seek expediency. ”In Romanticism and Biedermeier, until around 1830, at least bright splashes of color such as embroidered vests were common and also refined wavy or curly hair. From around 1820 onwards, men wore almost only inconspicuous dark colors. The military flourished in the 19th century, and gentlemen from aristocratic circles (such as Emperor Franz Joseph I ) very often wore uniforms that were also slightly laced at the waist. Men mainly had short hair, but from the 1830s, after a break of several centuries, full beards appeared again - sometimes of considerable size and length.

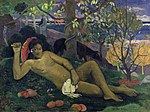

In the 19th century there was a certain interest in the Orient and in foreign cultures. This partly led to an interest in exotic beauty, which, however, was mostly represented in the form of pure fantasies, such as the Great Harem Odalisque by Ingres , and show a European ideal of beauty. Only towards the end of the century do women from completely different cultures with dark skin appear in the work of Paul Gauguin, who lived for years in Peru, Martinique and Polynesia, who are also portrayed as beautiful. However, it was very unusual around 1900 for a European painter to practically depict a dark-skinned Polynesian woman as in Gauguin's Te arii vahine as Venus.

François Gérard : Portrait of Madame Récamier , 1805. The sitter was a famous salon lady and recognized beauty in the Paris of the Empire .

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres : Charles-Joseph-Laurent Cordier, 1811

Joseph Karl Stieler : Auguste Strobl , 1827. This is the first lady that Ludwig I of Bavaria had painted for his beauty gallery (today: Nymphenburg Palace ). It is also an example of what is known as a 'gooseneck'.

Joseph Karl Stieler: Nanette Kaulla , 1829. Another portrait from the beauty gallery of Ludwig I.

Franz Xaver Winterhalter : Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha , 1842. The husband of Queen Victoria of England corresponded perfectly to the image of male beauty. Perfect growth and posture were also underlined in men by a slightly laced waist.

20th century

As early as the end of the 19th century, a sporting movement imported from America began, which gradually led to a fundamental change in the perception of the body. In addition, there are health considerations and emancipatory and revolutionary endeavors that were to determine the entire 20th century. It also includes a same ever-increasing public bathing culture with leisure travel to the sea - and with an increasingly liberal expectant swimwear that in the invention and dissemination (after 1950) of the first as shamelessly applicable bikini and nudism culminates (FKK). In the 20th century, the human body suddenly became publicly visible to a greater extent, yes, there was an emphasis on the body that inevitably also had an impact on the world of beauty ideals.

But after the turn of the century (but basically only after 1910), the corset slowly went out of use, after doctors had long been advised of consequential health damage. Instead, the so-called reform dress appeared, which propagated more natural body shapes and freer movements (among other things by the fashion designer Paul Poiret ).

Another revolution was the gradual sliding up of women's clothes hems, which in the “ Golden Twenties ” only reached below the knee - for the first time women showed their ankles and calves with it. This potentially erotic effect was initially counteracted by an otherwise rather unfeminine (or unfavorable) baggy, wide silhouette without a waist and with a breast flattened by a waist belt, although round, womanly shapes were still in demand in the interwar period . As a sign of their emancipated liberation, the completely new type of Garçonne also had short-cut hair, a red pout and black-rimmed eyes, as they were previously only known and cared for in the Orient. Pale complexions were still in fashion , and they were still protected by umbrellas. In more southern countries such as Spain or Portugal, parasols were still in use until at least 1960.

As early as the 1910s and even more so in the 1920s and 1930s, the stars of the new medium of film rose to become true idols, who also had a noticeable global influence on the world of beauty ideals . Celebrated worldwide as an almost mythical beauty and correspondingly influential as a role model was above all the “divine” Greta Garbo . At the beginning of her career in Sweden, she was rather plump and somewhat overweight, but before her first American film (1926) she was forced to lose weight by the Hollywood studio and transformed into a new and modern type of slim, ethereally elegant , slightly androgynous woman . In addition to her acting skills, the Garbo was admired for the flawless perfection of her facial features, and she was style-forming u. a. for actresses like Joan Crawford , Marlene Dietrich and Katharine Hepburn , and “over time” “even the mannequins in the department stores looked like her”.

Already at the beginning of the century - at first almost subliminally - the youth movement began to spread the ideal of a slim, youthful body shaped by sport . In addition to the “blond and blue-eyed” ideology, this was also widely propagated by the National Socialists between 1933 and 1945 and was to prevail, especially in the second half of the century, and to become a defining ideal. The complexion should now also correspond to a 'healthy' and 'natural' suntan, which, however, was not really established for women until around 1950 - not least because of the custom of going on vacation, which is also completely new for larger sections of the population, and in to indulge in a (luxurious) idleness in the sun. The tan was (and is) not only considered beautiful, but very often also as visible proof that you can afford a vacation.

After the Second World War , there was a certain renaissance of the lush female forms, which were emphasized even more by tight corsets that constrict the waist - that is, the traditional 'hourglass' type. Large breasts were also expressly ideal and emphasized by appropriate bras. This was ideally embodied by famous film stars such as Rita Hayworth , Marilyn Monroe , Gina Lollobrigida , Sophia Loren and Brigitte Bardot (among others) - who were also known colloquially as ' sex bombs ' (English: bombshell ). The ideal of extreme curves with simultaneous 'super slimness' of these male idols, however, was not achievable for the normal woman - who mostly could not or would not identify with the slightly vulgar image of the sex bomb, which is almost exclusively aimed at sexuality and the seduction of men.

At the same time, however, there was also a kind of counter-image in the films of the 1950s and 1960s of a young, slim, elegant and noble type who was less oriented towards sex and was also more accepted by women as a model of identification and beauty. Famous representatives were later to Princess of Monaco ascended Grace Kelly , Deborah Kerr , and in Europe, which is open until the early 1980s working Romy Schneider and Catherine Deneuve . The Belgian-English actress Audrey Hepburn belonged to this type of beauty , but at the same time she was a special case because she was naturally slim, almost 'skinny', had only small breasts and had bony shoulders. But she became an icon of beauty and elegance thanks to her romantic, spirited and delightful nature in her films, and because of her grace and grace (she was originally a ballet dancer ) , also by the fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy .

After the end of Hollywood's heyday in 1970 at the latest, the world of beauty also sought and found its role models in the world of the aristocracy and the international jet set with women such as Soraya , the ex-empress of Iran , or the Monegasque Princess Caroline , both of whom at least came from northern Europe -The German perspective depicted semi-exotic models that helped promote the ideal of a southern Mediterranean beauty with a tan - together with the Italian actresses Gina Lollobrigida, Sophia Loren, Claudia Cardinale and Ornella Muti . This tendency was continued in the early 2000s by the immense popularity of the ' Latino ' beauties Jennifer Lopez - who also influenced fashion with belly and (partly) hip-free outfits - as well as Salma Hayek and the Spaniard Penélope Cruz .

In addition to these female icons of beauty, male beauty and / or attractiveness also played an important role in (Hollywood) film and shaped the taste of the time, which, however, turned out to be much more constant or one-sided overall. From the heartthrob of the 1920s, Rudolph Valentino , about men like Nils Asther , Cary Grant , Gregory Peck , Laurence Olivier , Errol Flynn , Robert Taylor , Rock Hudson , Omar Sharif , Marcello Mastroianni , Pierce Brosnan , Richard Chamberlain , to George Clooney dominated for all individual differences and despite the most diverse origins, the 'classic' dark-haired elegant . There were also some blond men like Brad Pitt , but they were more of an exception.

In the fashion world of the 1960s, women's skirts become so short that the knees become visible, until finally the mini-skirt exposes the entire legs. Since the bikini is gaining ground in swimwear and holiday culture at the same time, for the first time ever in historically documented times the abdomen of women was publicly visible, and at least by young women it was almost constantly on display. The same applies to women's trousers, which became increasingly popular in the 1970s. The fashion developments described almost inevitably required a slim figure, and in fact the English model (and later actress) Twiggy became very well known in the mid-1960s and became a style icon who, like Audrey Hepburn, was slender, even thin. These exceptional women - who themselves were by no means enthusiastic about their great slimness - and the described fashion trends gradually initiated a development that continues to this day: in the fashion world, the ideal of the slim mannequin emerged, which was also developed for a woman reached the unusual 'ideal' height of about six feet. However, it was not until the 1980s and 1990s that only a few isolated 'supermodels', such as Cindy Crawford , Linda Evangelista , Naomi Campbell or Claudia Schiffer , achieved media fame that made them icons. Since the fashion industry also works with body measurements for chest, waist and hip measurements in centimeters, an 'ideal' arose for women, which is sometimes described with the formula 90-60-90 (calculated on approx. 80 m height!). Unfortunately, a regrettable consequence of this is that even today (as of 2018) many models, who by nature do not have such an unusually slim disposition, starve themselves to a weight that is far below their healthy ideal weight. This can lead to tragic eating disorders like anorexia or bulimia . Anorexia is said to have already existed in ancient China and the case of Empress Sissi described above is also known from the 19th century (see above).

As a high point in the modern physical exercise wave, bodybuilding was at times very popular in the 1980s ; The aftereffects of this can still be felt today, so the idea of a “ washboard abs ” is a modern ideal of beauty for men .

Hair color has never been so much the object of apparently interchangeable fashionable ideals of beauty as in the 20th and 21st centuries. Since the 1950s, ' hydrogen-blonde ' screen idols such as Marilyn Monroe, Brigitte Bardot, Grace Kelly and others have been used. a. blonde colored hair modern. To a lesser extent, some fake redheads such as Maureen O'Hara, Deborah Kerr, etc. a. contributes to the trend of colored hair. In any case, blonde in particular has been as modern and widespread since then as (presumably) not even in Roman antiquity and the Renaissance. In the second half of the 20th century, hair coloring was gradually perfected by the chemical industry, and such a wide range of different natural-looking color nuances came onto the market that it can be called a boom. Gray hair has been less noticeable since the late 20th century than ever before. After 1990, hair coloring became more normal even for men.

Jean Bérau : Blanche Ulman, around 1913

Joan Crawford in the typical flapper look, 1927

National Socialism: BDM girls at a gymnastics demonstration, 1941

Marilyn Monroe , ca.1957

21st century

Since the last quarter of the 20th century and even more so at the beginning of the 21st century, the ideal of beauty began to diversify, like many other social ideals. Cultural globalization is also responsible for this . While there was already contact with exotic cultures and foreign ideals of beauty through the world exhibitions or through individual artists such as Gauguin at the end of the 19th century , the world of film and television and the media has offered and continues to offer the possibility of large masses of individuals since the 20th century Personalities from other countries and cultures and from completely different and different origins suddenly become loved and revered confidants in their own living room. At the beginning of the 21st century there was a wave of enthusiasm for Indian Bollywood films in which a previously known enthusiasm for exotic beauty is evident. Such developments were and are at the same time promoted by the modern travel options, which enable a relatively large number of people to come into even more direct contact with foreign countries and cultures and the beauty of the people who live there. In addition, there is a mix of European countries with emigrants of various origins.

Since the 20th century there has been a tendency for fashion to set less strict limits than was the case in previous centuries. Your own appearance is to a certain extent a matter of choice, especially today. So is z. For example, the fashionable color palette for men has become much more colorful again since around 1990 than between around 1850 and 1980. Although the fashion industry is still trying to create fashion waves for hair colors, it is now (as of 2018) a question of choice Whether you dye your hair and which color is chosen, including tattoos on the skin - which became particularly fashionable after 2000 and which also represent an adoption of exotic ideals of beauty - are a question of choice. There has also been a special fashion for “overweight people” since the 20th century.

Triggered by film actresses such as Joan Collins or Jane Fonda , there has also been a trend in the western world since the 1980s that women who are over 40 or 50 are no longer necessarily classified as old (as before), but are still attractive and beautiful could be; that this sometimes requires a certain discipline ( dieting , sport) and tricks (hair coloring, make-up), and that there are natural limits, is obvious.

literature

- Nathalie Chahine, Catherine Jazdzewski, Marie-Pierre Lannelongue: Beauty. A cultural history of the 20th century . Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-88814-946-0 (In this illustrated book, the development of the ideal of beauty in the 20th century is traced from decade to decade.)

- Michèle Didou-Manent, Tran Ky, Hervé Robert: fat or thin? Body cult through the ages . Knesebeck, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-89660-031-1 ; Paperback edition: Bastei Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 2000, ISBN 3-404-60484-9 (In this book, a historian and two doctors follow the eternal change of the body shape that is considered desirable from prehistory to the media age.)

- Umberto Eco : The Story of Beauty. Hanser, Munich and Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-446-20478-4 ; Paperback edition: dtv, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-423-34369-9 (Opulent illustrated book on the cultural and intellectual history of beauty. The work documents the change in occidental aesthetic perception over the centuries, which is also reflected in the artistic representation of the human body as in architecture and philosophy.)

- George L. Hersey : Tailor-made seduction. Ideal and tyranny of the perfect body (Original title: The Evolution of Allure ). Siedler, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-88680-622-7 (representation of the ideals of beauty and their deviations from prehistoric times to the present; takes into account not only artistic but also political-sociological aspects.)

- Anne Hollander: Seeing Through Clothes. University of California Press, Berkeley 1993, ISBN 0-520-08231-1 (This book examines the changes in the representation of the body and clothing in Western art from the Greeks to contemporary films and fashion photography.)

- Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Berlin: Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 (3rd edition). (Not just about fashion, with a huge wealth of images.)

- Otto Penz: Metamorphoses of Beauty. A cultural history of modern corporeality . Turia & Kant, Vienna 2001, ISBN 3-85132-314-9 (The book by the sociologist Otto Penz traces the change in Western ideas about beauty in the 20th century. The prevailing body images are set in relation to the respective zeitgeist.)

- Ulrich Renz : Beauty - a science in itself . Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-8270-0624-4 . (This book reflects the state of modern research on attractiveness and investigates the regularities on which ideals of beauty and their eternal change are based.)

- Theo Stemmler (Ed.): Beautiful women - beautiful men. Literary descriptions of beauty . Lectures at an interdisciplinary colloquium, research center for European poetry of the Middle Ages. Narr, Tübingen 1988, ISBN 3-87808-532-X

- CH Stratz: The beauty of the female body. Dedicated to mothers, doctors and artists . 2nd Edition. Enke, Stuttgart 1899 ( digitized as PDF )

- Wilhelm Trapp: The handsome man. On the aesthetics of an impossible body . Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-503-06167-3 (In his dissertation, the literary scholar Wilhelm Trapp uses examples from literature to investigate the “feminization of beauty”, which began with the Renaissance and with the seizure of power by the bourgeoisie The woman has since been the “fair sex” - the beautiful man, on the other hand, is an “impossible figure” with something suspicious and unmanly attached.)

- Elizabeth Cashdan: Waist-to-Hip Ratio across Cultures: Trade-Offs between Androgen- and Estrogen-Dependent Traits. In: Current Anthropology Volume 49, 2008 (more lush shapes like the Venus von Willendorf or the Rubens figure are possibly due to the shortage of food in the Great (before 35,000 years) and Little Ice Age (in the 15th – 17th centuries) : [1] )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Researchers discover new 'golden ratios' for female facial beauty. Physorg, December 16, 2009.

- ↑ Nancy Etcoff: Survival of the prettiest: the science of beauty. Anchor Books, 2000.

- ^ W. Lassek, S. Gaulin: Waist-hip ratio and cognitive ability: is gluteofemoral fat a privileged store of neurodevelopmental resources? In: Evolution and Human Behavior. Volume 29, H. 1, 2008. pp. 26-34.

- ^ JL Anderson, CB Crawford, J. Nadeau, J. Lindberg: Was the Duchess of Windsor right? A cross-cultural review of the socioecology of ideals of female body shape. In: Ethology and Sociobiology. Volume 13, 1992, pp. 197-227

- ↑ CR Ember, M. Ember, A. Korotayev , V. de Munck: Valuing thinness or fatness in women: reevaluating the effect of resource scarcity. In: Evolution and Human Behavior. Volume 26 (3), 2005, pp. 257-270.

- ↑ Eric Colman: Obesity in the Palaeolithic Era? The Venus of Willendorf. In: Endocrine Practice. Volume 4, 1998, pp. 58-59.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Berlin: Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 (3rd edition), p. 40.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion - from antiquity to the present , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Berlin: Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 (3rd edition), p. 323.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 75-77, pp. 322-325.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 77.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 117.

- ↑ Fabienne Rousso: Beauty and its history. In: Nathalie Chahine, Catherine Jazdzewski, Marie-Pierre Lannelongue: Beauty. A cultural history of the 20th century. Schirmer / Mosel, Munich 2000.

- ^ Anne Hollander: Seeing Through Clothes . University of California Press, 1993, p. 97.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 102, p. 117.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 102, p. 117.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 127–136 (late Gothic Burgundian fashion), p. 139 (Italian early Renaissance).

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 127–136 (late Gothic Burgundian fashion), pp. 139–143, p. 343 (Fig. 551) (Italian early Renaissance).

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 362.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 129, 132, 136.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 526.

- ^ Anne Hollander: Seeing Through Clothes. University of California Press, 1993, p. 100.

- ^ Agnolo Firenzuola: On The Beauty of Women. Original: Discorsi delle bellezze delle donne. Approx. 1538. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia 1994, pp. 59f.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion, translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977, p. 144.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977, pp. 144 + 146.

- ^ Henry Samuel: "French king's mistress poisoned by gold elixir - The mistress of France's 16th century King Henry II was poisoned by a gold elixir she drank to keep herself looking young, scientists have discovered.", In: The Telegraph , December 22nd Online 2009 , viewed June 12, 2018.

- ↑ This and other information about the Diane de Poitiers beauty recipes in the French program: "Visites privées - Éternelle jeunesse", "Diane de Poitiers - Visites privées" (French) (published on Youtube: February 8, 2017; section on gold at : 6:15 min - 9:10 min), as seen on June 12, 2018.

- ↑ The French broadcast reported on the excavation and investigation of the remains (bones) of Diane de Poitiers in 2008: "Secret d'histoire: Catherine de Médicis et les châteaux de la Loire", "(French) (published on Youtube: February 8, 2017; excavations in Anet and intended investigations of the bones (for gold) by Philippe Charlier, Joel Poupon et al., At: 27:45 min - 31:40 min), seen on June 12, 2018.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977, p. 154, p. 163–164.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 154, p. 163–164, p. 172 (Fig. 239), p. 574.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 177–187.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 186–187.

- ↑ A well-known example is Mademoiselle de la Valliére, the first maitress of Louis XIV, who was generally found likeable and lovable, but too thin and lean. Gilette Ziegler: The court of Louis XIV. In eyewitness reports . Rauch, Düsseldorf 1964, p. 38f.

- ↑ Maitressen of Louis XIV were z. B. meticulously 'inspected' for their respective merits and described by the famous letter writers and biographers of the time, u. a. by Liselotte of the Palatinate. Gilette Ziegler: The court of Louis XIV. In eyewitness reports . Rauch, Düsseldorf 1964, p. 122.

- ^ Gerhard Hoyer: The beauty gallery of King Ludwig I, Schnell and Steiner, 7th edition 2011, p. 30.

- ↑ Francesco Petrucci: Il Palazzo Chigi di Ariccia (official guide, Italian), p. 14.

- ↑ Gerhard Hoyer: The beauty gallery of King Ludwig I, Schnell and Steiner, 7th edition 2011, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Gerhard Hoyer: The beauty gallery of King Ludwig I, Schnell and Steiner, 7th edition 2011, p. 31.

- ↑ 'that famous and indeed incomparable beauty'

- ↑ L. Kybalová, O. Herbenová, M. Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 , pp. 177 + 187.

- ↑ L. Kybalová, O. Herbenová, M. Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 , p. 474.

- ↑ L. Kybalová, O. Herbenová, M. Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion , translated by Bertelsmann, 1967/1977, p. 177.

- ↑ L. Kybalová, O. Herbenová, M. Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion , translated by Bertelsmann, 1967/1977, p. 207.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 222-259, p. 263.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 346.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 265–266.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 470, 473, 474, 476 f.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 271.

- ↑ Gerhard Hoyer: The beauty gallery of King Ludwig I, Schnell and Steiner, 7th edition 2011, pp. 29–30

- ^ Gerhard Hoyer: The Beauty Gallery of King Ludwig I, Schnell and Steiner, 7th edition 2011, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Gerhard Hoyer: The Beauty Gallery of King Ludwig I, Schnell and Steiner, 7th edition 2011, pp. 62f, 70–73, 80f, 86f, 96f, 110f, 116f.

- ↑ Gerhard Hoyer: The beauty gallery of King Ludwig I, Schnell and Steiner, 7th edition 2011, pp. 29–30

- ^ Gerhard Hoyer: The beauty gallery of King Ludwig I, Schnell and Steiner, 7th edition 2011, p. 34.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : p. 228.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion ,…, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: pp. 262–265.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion ,…, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : pp. 272–274.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The large image lexicon of fashion , ..., Bertelsmann, 1967/1977 : p. 265.

- ↑ Ludmila Kybalová, Olga Herbenová, Milena Lamarová: The great image lexicon of fashion , translated by Joachim Wachtel, Bertelsmann, 1967/1977: p. 474, p. 477 (Fig. 785: Various parasols in Vogue from 1928).

- ↑ This is not only easy to verify in photos and films, but has also been emphasized again and again by various people, e.g. a. by Stella Adler , Louise Brooks , and by their film directors and cameraman William H. Daniels . Barry Paris: Garbo , Berlin: Ullstein, 1997, p. 330.

- ↑ This was already noticed in 1932 by the magazine Vanity Fair , which made a comparison and published photos of various actresses “before Garbo” and “after Garbo”. Barry Paris: Garbo , Berlin: Ullstein, 1997, pp. 331-332.

- ↑ Mercedes de Acosta: Here lies the heart , New York 1960, p. 315 (here after Barry Paris: Garbo , Berlin: Ullstein, 1997, p. 331.)

- ^ Norbert Stresau: Audrey Hepburn , Munich: Wilhelm Heyne ("Heyne Filmbibliothek"), 1985, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Norbert Stresau: Audrey Hepburn , Munich: Wilhelm Heyne ("Heyne Filmbibliothek"), 1985, pp. 50–52.