Akhenaten

| Name / title before renaming (1st section of government, year 1 to 5) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Model bust of Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten), replica

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

K3-nḫt-q3j-šwtj Strong bull with a high pair of feathers |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Wr-nsyt-m-Jpt-swt Great to royalty in Karnak |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Wṯs-ḫˁw-m-Jwnw-šmˁj Who rises the crowns in southern Heliopolis ( Hermonthis ) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Nfr-ḫpr.w-Rˁ-wˁ-n-Rˁ With perfect forms, only one of the Re |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

Jmn ḥtp Amun is satisfied

(Amen hotep netscher heqa Waset) Jmn ḥtp nṯr hq3 W3st Amun is satisfied, God and ruler of Thebes |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Greek for Manetho |

Flavius Josephus : Ἀκεγχερής Akencherēs Achencherses, Acherres, Kenkeres |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Akkadian | Na-ap-ḫu-ru-ri-ia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Name / title after renaming (2nd government section, from year 6) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

3ḫ n Jtn The Aton serves / is useful; Ray / shine of the Aton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

Nfr-ḫpr.w-Rˁ-wˁ-n-Rˁ With perfect forms, only one of the Re |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

Mrj-Jtn Loved by Aton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

Wr-nsyt-m-3ḫt-Jtn Great to kingship in Achet-Aton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Wṯs-rn-n-Jtn Who lifts up the name of the Aton |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Akhenaten ( birth name Amenhotep IV .; Egyptian Amenhotep IV .; Later Achenaton ) was an ancient Egyptian king ( pharaoh ) of the 18th Dynasty ( New Kingdom ) and son of Amenhotep III. and Queen Teje . He raised the god Aton in the form of the solar disk to be god above all the gods of Egypt and consecrated his new capital Achet-Aton to him . This ruler pursued a strictly inward policy and reformed the arts.

Akhenaten's reign is dated differently: approx. 1351–1334 BC. BC, 1340-1324 BC BC ( Helck ) or 1353–1336 BC Chr. ( Krauss ).

To his name

- Amenhotep (IV.) ( Hieroglyphic transcription : Jmn ḥtp ): original Egyptian birth name

- Ach-en-Aton (direct and complete hieroglyphic transliteration [gods in hieroglyphic writing preceded]: Aton-ach-en, transcription: Jtn-3ḫ-n , shortened: Aton-ach, Jtn-3ḫ ; transcription according to sentence statement: 3ḫ-n- Jtn = The Aton serves or The Aton is useful ); the probably Egyptologically correct pronunciation of his new name (i.e. the transliteration of the hieroglyphs) in German: Akhenaten.

There is no verifiably correct pronunciation of New Egyptian due to the lack of an exact tradition of the vowels . According to the (traditional) Coptic , the most recent form of Egyptian, passed on in the liturgy of the Coptic Church , and other ancillary traditions , only the pronunciation " Amanchatpa " or Achan-jati (n) can be reconstructed .

family

- Father: Amenophis III.

- Mother: Teje

- Siblings: Thutmose , Sitamun , Iset , Henuttaunebu , Nebet-tah , Baketaton , " Younger Lady "

- Wives: Nefertiti , Kija , “Younger Lady” (according to the DNA tests a sister of Akhenaten and mother of Tutankhamun, controversial), Taduchepa

- Sons: Tutankhamun (controversial)

- Daughters: Meritaton , Maketaton , Anchesenpaaton , Neferneferuaton tascherit , Neferneferure , Setepenre .

Life and religion

Adolescence

Little is known about the youth of Amenhotep IV. From the royal palace of Malkatta only one jar stopper has survived, which tells of a "domain of the real king's son Amenhotep". Amenophis only took over the role of heir to the throne after the early death of his older brother Thutmose. He is estimated to be between 18 and 22 years old at the time of the accession to the throne. Whether he married Nefertiti before or after can only be guessed, but his eldest daughter Meritaton is born in the first year of reign.

Accession to the throne

Amenophis IV was named under the throne name Nefer-cheperu-Re, Wa-en-Re (means "beautiful are the figures of Re, the only one of Re", nickname Anch em Maat ("who lives from the Maat") and thus with Reference to the god Re and the goddess Maat ). Whether he was initially co-regent in the last years of his father's reign is highly controversial in Egyptological science , but has been rejected in recent years. Evidence for this were titles that refer either to Upper or Lower Egypt (el-Mahdy), which, however , are invalidated by Hornung's thesis : There is supposed to have been a rivalry between Upper and Lower Egyptians , which is also reflected in the different accentuation of the main god should have expressed. In this context, the work of Rolf Krauss on the chronology of the Amarna period is particularly important , which makes co-regency, which should also be rejected for reasons of content, as good as impossible.

Change of political course

Even his father Amenophis III. had worshiped the sun god Aton more, especially since there were internal contacts to the kingdom of Mitanni (and the Hittite empire ), where the sun was also the main deity. His son and successor, however, went one step further: in his sixth year of reign he built a new city as the main cult center of Aton, which he also made his seat of government. In the same year of reign Akhenaten also had an Aton shrine built in the area of the Karnak Temple east of the Amun district.

The colossal statues found here give an indication of Akhenaten's religious and political development. Commissioned in his youth, they make a reference to the triad of the original creator gods Atum , Schu and Tefnut and thus symbolize a return he intended to the foundations of the Egyptian gods. The cult of these gods of origin had been supplanted by the worship of their descendants; however, Akhenaten's return to the first three gods made the cults of other gods less important. Later, in the Amarna period , Aton became the most important, though not the only, imperial god.

Aton, originally the figure of the sun god in the evening, in the form of the sun disk became the symbolic personification of the imperial god and the source of all life.

Until the time of Akhenaten, the sun god was traditionally represented as Re-Harachte with a human body, a falcon's head and the sun disk above, always in a side view. This type of representation meant that only one person could face God at a time. In the tradition of the ancient Egyptians, this was always the pharaoh. Under Akhenaten in the Amarna period, the human body was generally completely dispensed with when depicting the sun god Aton and this god was depicted as a forward-facing sun disk with hands at the ends of the sun's rays. As a result, the king and queen could now benefit equally from the signs of life of the sun god.

Amun-Re was transcended to a hidden god during the 18th Dynasty, who was the source of all being and the source of all life. In educated circles all other gods were only considered to be his manifestations. His priesthood, too, had become arbitrary and rich, although according to the old tradition the Pharaoh was supposed to be the real Supreme Priest and mediator.

For the time being, the pharaoh managed, on his own orders, to reject and suppress the forms of the imperial god, which were felt to be superfluous, and at the same time to disempower the powerful priesthoods. The Pharaoh and his wife became the representatives of this God on earth, as in the old days, who did not need a caste of priests. The Pharaoh alone could impart the blessings of the Most High God to the people, the Aton cult evidently had henotheistic traits. A special depiction of Nefertiti on three stone blocks is seen by researchers as evidence that Nefertiti Akhenaten served as high priestess. The people themselves were not allowed to pray to God directly, but had to take Pharaoh and his wife as intercessors.

In the rock grave of former officials and later Pharaoh Ay and in other tombs of the era of Akhenaten was Atonhymnus found. Amenhotep IV called himself Akhenaten after his religious reforms and only changed his birth name. In all official representations only the name of the throne is mentioned. Akhenaten's name change was therefore not a revolution, but his personal affair.

Since he did not deny their existence, he did not forbid the cult of the other gods. Nevertheless, there were riots against the priests and the old names of gods on the monuments (even if it was locally limited to Thebes ). An arrangement by Akhenaten could not be proven. In his own city (but only in the domestic area) a multitude of other gods continued to exist and with the knowledge of the Pharaoh.

Religious implications

There are several theories in science regarding the scope of these political-religious decisions:

- Akhenaten wanted to introduce monotheism - but the people, the priests and others resisted it; therefore there are archaeological evidence for other gods.

- Akhenaten only wanted a preference for the god Aton ( monolatry ).

- Akhenaten wanted monotheism, withdrew to his city Akhet-Aton and left the country to itself; Akhet-Aton was therefore a religious enclave, Akhenaten was indifferent to the rest of the country.

- Akhenaten wanted to introduce a henotheism - but the rest of the people and their officials found it difficult. The other gods continued to be tolerated in a kind of transition phase. Religion never got beyond this transition phase, and after Akhenaten's death the representatives of the old order prevailed.

Most Egyptologists rate Akhenaten's religion as a short epoch of henotheism, which, however, represented a decisive turning point in polytheism . Jan Assmann therefore compares this incision as implied monotheism, which, however, does not yet meet the full definition of later monotheism.

Achetaton is founded

| Achetaton in hieroglyphics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Achetaton (Achet Aton) 3ḫ.t Jtn horizon of the Aton |

|||||

During the reign of his father, Amenhotep III. (A co-regency is now ruled out), he founded a temporary residence in Sisala , where he stayed to hold a jubilee celebration in honor of his father and led the celebrations. In this he followed the example of his father, who had also founded a new residence in Malkata. In the end, however, he chose another location, 400 km north of the former capital Thebes, downstream on a larger sandy area in Middle Egypt on the east bank of the Nile surrounded by rock formations . Almost exactly between Memphis in the north and Thebes in the south Akhenaten believed he recognized the hieroglyphic sign for "horizon" (= Achet) with the mythological meaning of "beginning and end" when he was with a chariot made of gold and silver had dragged downstream for some time.

Akhenaten therefore decided in his 5th year of reign on 13 Peret IV (March 5th July / February 21st greg. ) To found his new capital Akhetaton ( horizon of Aton ) near today's Amarna:

“I am building Achetaton for Aton, my father, in this place ... I am not crossing the southern stele of Achetaton to the south, I will not cross the northern stele of Achetaton to the north in order to build Achetaton there. Also I am not building it for him (Aton) on the west side of Akhetaten, but I am building Akhetaten on the side of the sunrise , in a place that he has prepared for himself and that is framed for him by a mountain range ... Build me a grave in the mountain of Achetaton, where the sun rises, in which my burial is to take place after millions of government anniversaries ... After millions of years the great royal wife Nefertiti is buried in it ... and after millions of years the royal wife is buried in it Daughter Meritaton. "

|

|

|

|

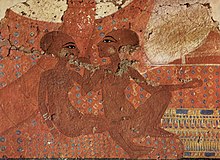

Fragments of Akhenaten's statues from Karnak (exhibited in the Louvre (left) and in the Luxor Museum ) |

||

Achetaton is - besides Alexandria - the only planned city from ancient Egypt and contains some foreign elements. The road from the residence to the temple is particularly wide, so that the king can ride in a chariot, reminiscent of the journey through the sun .

Move to Achetaton

The construction work was advanced in record time by involving the population and especially the military in the work. In the 8th year of the reign, Achetaton was officially handed over on 30 Achet IV (November 21st July / November 9th greg. ). Winfried Barta suspects this date to be Akhenaten's original coronation day in 1353 BC. Chr.

The theory that Akhenaten was expelled from Thebes is therefore untenable. Akhenaten was just as great a builder as Ramses. The entire Egyptian court and administration moved with the royal couple to the new capital, the archive with the foreign policy correspondence was also taken away. The temples were built with an open roof - in remembrance of the sun temples of the 6th Dynasty - so that its beneficial rays could penetrate.

Domination

The reign of Akhenaten and his great royal wife Nefertiti ("the beautiful one has come") was often said to have a love for art and spirituality . It is controversial whether Akhenaten was not interested in foreign policy issues and whether his mother Teje took care of them instead; as an argument for this one can cite letters which are expressly addressed to Teje and not to Akhenaten. But these letters are rather the exception and come from the beginning of his reign, when Teje was already a well-known figure for the neighboring states and the new ruler could not yet be classified abroad. Akhenaten and Nefertiti saw themselves like all other pharaohs as gods on earth, but now as representatives of the main god in the form of Aton, and they were the sole high priests of this cult. The mediation between God and believer took place exclusively through the ruling couple as the sole reference to Aton. They allowed themselves to be worshiped like gods and, according to statements by Egyptologists, formed a kind of trinity together with the god Aton, which comes closer to the oriental religions of the Mesopotamia.

Nefertiti co-reign

The strong position of women in ancient Egypt was increased under Akhenaten. Nefertiti, as the Pharaoh's main wife, was made into a kind of co-regent and at least equipped with the pharaonic symbols of power. Later she was even depicted in the rock tombs of Amarna together with Akhenaten several times in a way that researchers even assume a dominant co-reign of Nefertiti in the later reign of Akhenaten.

Foreign policy situation

By a happy coincidence in 1885 (AD) around 300 tablets written in Babylonian cuneiform were found in the ruins of the city of Amarna: Akhenaten's foreign policy correspondence and his successors. These so-called Amarna letters reflect the political situation in Egypt, influenced by the strong empire of the Hittites , which was still in existence at the time of Amenhotep III. north of the Asian zone of influence of Egypt.

So here Schuppiluliuma I , the king of the Hittites, welcomes Akhenaten to his accession to the throne. For the inauguration of the new capital Akhet-Aton, a Hittite delegation appeared with presents. But a short time later the Hittite king asks why his letters are not being answered.

The reason for the tensions that arose was the fall of some Syrian vassals from Egypt and their turn to the Hittite sphere of influence. Abdi-Ashirta and his son and successor Aziru ruled over the kingdom of the Amurites on the upper Orontes for a long time . She and the Syrian prince Itakama von Kadesch later switched sides. Except for the cities of Simyra and Byblos , Aziru conquered all northern Syrian and Phoenician coastal cities. The background was the appointment of the previously equal Abi Milki as governor for the entire region. After his appointment, Aziru and Zimrida of Sidon terminated the alliance. Together with the Hittites he conquered Nija and advanced against the city of Tunip .

The call for help from the city elders to the Pharaoh has been preserved: “Who could have plundered Tunip in the past without Manachpirija ( Men-cheperu-Re ) plundering him as a punishment? ... and if Aziru penetrates Simyra, he will do for us what he pleases in the domain of our lord the king, and in spite of all that our lord holds back from us. And now your city Tunip is crying and its tears are flowing, and there is no help for us. ... we have sent messengers to our Lord, the King of Egypt, but we have received no answer, not a single word. "

RibAddi from Byblos repeatedly asked Akhenaten for help against Azirus' troops in their attack on Simyra, but in vain. Simyra was destroyed, the Egyptian envoy slain. More than 60 letters from the Rib-Addi asking for help have been found in Amarna.

Resistance rose in Palestine among the Apiru , who threatened Megiddo , Askalon and Gezer and ultimately brought them under their control. The calls for help from this region only led to half-hearted and unsuccessful measures by the ruler in Achet-Aton. So the territories were lost to the empire. This is the background against which the Haremhab officer rose to later become pharaoh.

Death and succession

Akhenaten's death remains unexplained. He died in the 17th year of his reign and was probably first buried in the new royal tomb of Amarna . An examination of the tomb revealed fragments of the sarcophagus and some evidence of the burial equipment. Reeves sees an unfinished grave for Akhenaten in WV25 in the Valley of the Kings (western valley). There are suspicions that Akhenaten was the victim of an attack because his policies were interpreted as a violation of the Maat . For this reason he was apparently a victim of the damnatio memoriae ("eradication of remembrance") customary in Egyptian culture , so that he was forgotten until his grave was discovered. After his reign, the rulers quickly replaced each other, which was interpreted as succession disputes and does not make violent attacks unlikely, especially since Akhenaten's only son, the heir to the throne Tutankhamun, was still a toddler when his father died or Akhenaten even died without a male successor (see grave and Mummy).

At first it seems between the queen widow Kija, who was of foreign descent and is presumably identical to the Mitanni princess Taduchepa , who Akhenaten from the harem of his father Amenophis III. took over, and his eldest daughter Meritaton came to the battle for the throne. Kija is likely to be the person responsible for the Dahamunzu affair by asking the Hittite king for one of his sons as husband and future king for Egypt in order to consolidate her precarious position at the Egyptian court. Even before this happened, Kija was ousted by her rival and the potential Hittite husband was murdered on the way to Egypt.

After her accession to the throne , Meritaton married Semenchkare , whose identity is unknown, but who probably came from a side line of the royal family. A theory, which was controversial from the start and has since become outdated, states that, contrary to all previous assumptions, Nefertiti survived Akhenaten and ascended the throne after him under the name of Semenchkare. The depiction of Nefertiti as the patron goddess of her deceased husband on the corners of the stone sarcophagus of Akhenaten (in the garden of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo) and a small relief depicting Nefertiti slaying enemies was interpreted as meaning that after Akhenaten's death she even ruled Egypt alone for a short time. It is still partly claimed that Semenchkare was actually female (cf. Cyril Aldred). In addition, both the throne name assigned to Semenchkare (Ankh-cheperu-Re) and his proper name contained the addition “meri-wa-en-Re” ( Beloved by the only one of Re ), with “wa-en-Re” being part of Akhenaten's throne name . In the meantime, however, serious research no longer questions the fact that Nefertiti died a few years before Akhenaten. Some sources give the 12th year of reign as the date, other sources the 14th year of Akhenaten's reign. In December 2012 it became known that an inscription was found in a quarry near Dair al-Berscha , north of Amarna, in which Nefertiti is named as the ruling queen. It was written on the 15th day of the third month of the flood season of the 16th year of Akhenaten's reign. The third line begins with the words “Great Royal Wife, His Beloved, Mistress of the Two Lands, Neferneferuaton Nefertiti”.

Grave and mummy

Akhenaten originally had a grave built at Amarna for himself and his family (Amarna grave 26). His second daughter Meketaton was probably buried here after her untimely death; a child-sized sarcophagus could be reconstructed from fragments. Whether Akhenaten himself was buried in Amarna 26 is unknown, as no clear traces of other burials could be found.

In January 1907, Edward Russell Ayrton's grave, now known as KV55 , was found in the Valley of the Kings . It contained grave goods with the names of various people and a mummy from the late 18th dynasty, which was already in very poor condition and disintegrated into a skeleton during the first investigations. Probably because of the coffin originally made for a woman, the arm posture typical of female burials and the already disintegrated male genitals, the mummy was first mistaken for a woman. Grafton Elliot Smith examined the mummy a few months later and identified a young man around 25 with unusually wide hips and an unusual head shape, possibly due to hydrocephalus . However, Smith later suggested the possibility that the man might have suffered from Fröhlich's syndrome . This slows down the normal development of bones, among other things, and would have made a higher age possible. So the mummy was u. a. Smith, Gaston Maspero and Arthur Weigall as Akhenaten. After the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun ( KV62 ), the similarity of the mummies was noticed and the same blood group was found for both, so that a relationship is considered likely.

However, later investigations found no evidence of slowed bone development, denied hydrocephalus and even reduced the age of death to only 20 years. Such an age rules out identification with Akhenaten, as Akhenaten became a father in the first year of his 17-year reign and can therefore only have died in his early 30s at the earliest. Since the identity of the mummy is closely related to the time of death, the remains have been examined several times over the years with very different results: Besides Smith, Douglas Derry and Ronald Harrison also came to an age of 25-26 years. Two studies put the mummy at around 35, Joyce Filler at her early twenties and Eugen Strouhal at only 19-22. In 1831 Rex Engelbach was the first to propose that the mummy be identified with Semenchkare , a successor of Akhenaten about whom little is known and who in this case could have been an older brother of Tutankhamun.

In 2010, genetic tests were carried out on a number of mummies from the expiring 18th dynasty. Through this the mummy of Queen Teje could be identified. It was found that the mummy from KV55 and the so-called Younger Lady were children of Amenhotep III with high certainty . and Teje, as well as Tutankhamun's parents. To explain the young age of the mummy from KV55, a computed tomography scan was carried out and the age of death of the mummy was set at 35-45 years.

The latter result quickly led to disagreement on the part of several experts. They criticized the fact that only a single indication of older age was given (a degenerative change in the spine), as well as the lack of explanation for the frequently cited indications of a young age. Eugen Strouhal even denied that a degenerative change in the spine could be detected at all.

Another problem is that the KV55 mummy cannot be the father of the KV21A mummy. She was identified as the possible mother of the stillborn fetuses from Tutankhamun's grave. In this case it would have to be Akhenaten's daughter Ankhesenamun , since no other Queen Tutankhamun is known. Kate Phizackerley pointed out that the DNA of the fetuses excludes the mummy from KV55 as a mutual grandfather, since in this case the mother of the fetuses would not have all of the alleles present.

While many believe that the mummy from KV55 is indeed Tutankhamun's father (Strouhal believes an older brother is more likely), the identification with Akhenaten continues to be very controversial. The opponents of this theory consider him a Semenchkare, about whom little is known that he can neither be excluded as a father nor as a brother of Tutankhamun. There is only a certain consensus that the ancient Egyptians, who destroyed the grave and desecrated the coffin, were convinced that the mummy was Akhenaten.

Effects of Akhenaten's rule

As a counter-image of an idyllic community, Akhenaten's rule is also referred to as "the black period in the history of ancient Egypt". Accordingly, under Akhenaten there were negative effects on the priesthood of temple closure, persecution, confiscation of goods, neglect of the images of the old gods. This earned him the nickname " Heretic Pharaoh " in research . The brief phase of upheaval did not, however, shake the foundations of the Egyptian religion . Even if the people turned to Aton for a short time, they had never ceased to worship the old gods. Likewise, the old priesthood in Thebes apparently continued to exist at the same time to a certain extent. In addition, it appears that Egypt suffered an economic decline at that time due to the central government's withdrawal into the desert.

In terms of foreign policy, Akhenaten is said to have caused the loss of several Egyptian protectorates in the north by refusing military aid for the Egyptian allies threatened by the Hittites . In recent times, however, there has been a shift towards seeing these nations asking for help not as part of Egypt, but as completely autonomous states that turned to Egypt as the strongest country. It seems as if the pharaohs specifically promoted and supported certain countries in order to keep the power structure in balance. Failure to provide assistance does not have to be a mistake, it can also have been a political calculation .

As the pharaoh of a religious reformation, whose model u. a. in the world of shepherds in the east, such as the Midianites , and a cultural revolution , Akhenaten has taken the last logical steps of a tendency that was already underway during the reign of his father Amenhotep III. was created. The so-called New Solar Theology was under Amenophis III. has become more and more important, the last commemorative scarab (the so-called Lustsee-Scarab ) from the 11th year of the king mentions a barque with the name Shining Aton

art

During the reign of Akhenaten, the art of the Amarna flourished, which is characterized by the development of nature-imaging art , which is teeming with plants, flowers and birds. The Amarna floors are famous to this day with their abundance of floral and animal decorations.

Another feature is the extremely realistic portrayal of the personalities, which sometimes even exaggerates to the point of caricature ; traditional art was rather idealizing. Likewise, the previous art rules of lack of perspective and statics have largely been repealed.

On a relief in which Akhenaten holds out an olive branch to Aton, his hand is worked out flat, almost unique in the Amarna period and unique in the overall context of Egyptian art history. The sculptors boast that they were instructed in the execution of the new style by the Pharaoh himself; the plans for the city of Achet-Aton are said to go back to him. Akhenaten is also said to have poetic talent (see Aton hymn ).

The subsequent pharaohs from Haremhab did everything to erase the traces of the heretical pharaoh, so that very little is known about this period. Even if after Akhenaten there was a return to the old conditions, much has been preserved. The sun disk played a prominent role in the 19th and 20th dynasties. Future royal tombs were laid out without a bend axis and straight so that the sun's rays could fall directly. In art, elements of the Amarna style were able to assert themselves for a short time.

Theories and speculations

It is believed that Akhenaten suffered from a hormonal disorder known in medicine as acromegaly .

There are theories that place the biblical Moses (who according to biblical tradition Ex 2.1ff EU grew up in Egypt ) and his image of God in direct relation to Akhenaten and which depict the Egyptian Aton belief in the Jewish Adon belief of the Pentateuch with great attention to detail see. Sigmund Freud, for example, in his age study " The Man Moses and the Monotheistic Religion " regards Jewish monotheism as the legacy of Akhenaten's religion that was conveyed through Moses.

The thesis that Akhenaten forms a personal unit with Moses due to multiple correspondences is rejected by most researchers. Chronologically, the time of the Israelite conquest following Moses is usually not connected with the time of Akhenaten, but is dated one or two centuries later to the time of the Ramessids .

There is also no historical evidence of Akhenaten's encounter with the biblical Joseph , as portrayed in Thomas Mann 's Joseph novels . The Egyptologist Jan Assmann often draws parallels between the two, but rules out direct acquaintance.

In 1907 an alleged toe of the Pharaoh came to Europe. Where it was then stored is unknown. With the mediation of the Swiss mummy scientist Frank Rühli , the body part could be brought back to Egypt in April 2010 and, according to the antiquities administration, will in future be on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Research Chronology

Akhenaten is one of the most controversial figures in Egyptian history. Especially shortly after his rediscovery, the wildest theories circulated among Egyptologists : he is said to have been a woman, to have been castrated on a Nubian campaign or to have been an outcast priest of Re .

- 1714: Claude Sicard , a traveling Jesuit , notices one of the border steles of the city of Amarna (stele A).

- 1798–1799: Napoleon's Egyptian expedition discovered the associated city, published in Description de l'Egypte .

- 1826: John Gardner Wilkinson and James Burton return to Amarna, complete the work and publish the results in the multi-volume work Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians , with sketches, impressions of the reliefs and plans.

- 1828: Champollion visits Amarna, but devotes only one day to the city. His impressions of Akhenaten ( grotesque ) are often quoted.

- 1845: The authoritative work Aegyptensstelle in the world history by Christian KJ Bunsen appears in three volumes. Here Akhenaten still appears as a woman, and “Amentuanch” as the Nubian antagonist. In the fourth volume, Bunsen corrects Akhenaten's gender.

- 1851: Karl Richard Lepsius publishes his research results, including not only Akhenaten's true gender, but also the knowledge that there have been monotheistic endeavors and counter-movements. He suspects influences from Ethiopia or the Middle East . He considers Teje to be a bourgeois woman and Akhenaten to be a priest of Re. A reprint of the work was published in 1981 ( on the first Egyptian group of gods and their historical-mythological origin ). The popular belief that Akhenaten was a woman is corrected by the publication.

- 1859: Heinrich Brugsch publishes the first history of Egypt under the pharaohs and covers Akhenaten on five pages. He draws a comparison between Aton and Adonis , which later u. a. is taken up by Sigmund Freud .

- 1887: A Fellachin discovered the clay tablet archive with 380 tablets. She sells them to a neighbor, who breaks them up and sells them to various antique dealers who, however, reject it as a fake due to the written language used.

- 1891/1892: The grave is cleared under the “theoretical supervision” of Alessandro Barsanti , the “man for all occasions” of the Egyptian Antiquities Administration.

- 1891/92: Flinders Petrie carries out excavations in Amarna. He is dedicated to u. a. the workshops and the utensils and decorative items.

- 1892: Howard Carter uses his service at Petrie to visit the royal tomb. He makes copies of the most important scenes, which he sells to the English magazine The daily Graphic . They appeared on March 23, 1892.

- 1907: Theodore M. Davis discovers grave KV55 . A connection to Akhenaten has been established, but it is unclear. Many opinions exist, including that Akhenaten was buried there.

- 1911–1914: The German Orient Society (DOG) digs under the direction of Ludwig Borchardt . In 1912 the bust of Nefertiti was found, on January 20, 1915 the later controversial division of the find took place.

- 1925/26: The Akhenaten Colossi are discovered in Karnak .

literature

Biographies

- Bernhard Albers: Akhenaten. The fall of a family. an essay (= Rimbaud-Taschenbuch. No. 83). Rimbaud , Aachen 2013, ISBN 978-3-89086-453-2 (contains: Chapter 1: Akhenaten as an artist ; 2: The sun song of Akhenaten .; 3: Akhenaten in the opera. )

- Cyril Aldred: Akhenaten. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1968.

- Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Volume I: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, London 2008, ISBN 978-1-905299-37-9 , pp. 13-18.

- Johannes Bertram: Akhenaten, the great one in looking. A study of the philosophy of religion. Hamburger Kulturverlag, Hamburg 1953.

- Michael E. Habicht : Nefertiti and Akhenaten. The secret of the Amarna mummies. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 2011, ISBN 978-3-7338-0381-0 .

- Erik Hornung : Akhenaten. The religion of light. Artemis, Zurich 1995; Patmos, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-7608-1111-6 , ISBN 3-491-69076-5 .

- Franz Maciejewski : Akhenaten or the invention of monotheism. To correct a myth. Osburg, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-940731-50-0 .

- Susanne Martinssen-von Falck: The great pharaohs. From the New Kingdom to the Late Period. Marix, Wiesbaden 2018, ISBN 978-3-7374-1057-1 , pp. 99–113.

- Peter Priskil : Akhenaten - dreamer, fanatic or revolutionary? Ahriman, Freiburg 2001, ISBN 3-89484-704-2 .

- Nicholas Reeves : Akhenaten. Egypt's false prophet (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 91). von Zabern, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-8053-2828-1 .

- Hermann A. Schlögl : Amenophis IV. Akhenaten. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986, ISBN 3-499-50350-6 .

- Hermann A. Schlögl: Akhenaten. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56241-9 .

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 66-71.

To the Aton religion

- Jan Assmann : Moses the Egyptian. Hanser, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-446-19302-2 .

- Hazim Attiatallah: Monotheism Before Akhenaten's Time. In: Göttinger Miscellen . (GM) No. 121, Göttingen 1991, pp. 19-24.

- Mubabinge Bilolo : Le Créateur et la Création dans la pensée memphite et amarnienne. Approche synoptique du "Document Philosophique de Memphis" et du "Grand Hymne Théologique" d'Echnaton . Munich 1988, 2nd edition, Paris 2005, ISBN 978-2-911372-34-6 .

- Sayed Tawfik: Aton Studies / 1: Aton Before the Reign of Akhenaton. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK) No. 29, von Zabern, Mainz 1972, pp. 77-86.

- Sayed Tawfik: Aton Studies: 3. Back again to Nefer-neferu-Aton. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 31, von Zabern, Mainz 1975, pp. 159-168.

- Sayed Tawfik: Aton Studies: 4. Was Aton - The God of Akhenaten - Only a Manifestation of the God Re '? In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 32, von Zabern, Mainz 1976, pp. 217-226.

- Sayed Tawfik: Aton Studies: 5. Cult Objects on Blocks from the Aton Temple (s) at Thebes. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 35, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, pp. 335-344.

- Sayed Tawfik: Aton Studies. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 37, von Zabern, Mainz 1981, pp. 469-473.

- Sayed Tawfik: Aton Studies. : 7. Did any daily cult ritual exist in Aton Temples at Thebes? An attempt to trace it. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 44, von Zabern, Mainz 1988, ISBN 3-8053-1039-0 , pp. 275-281.

Questions of detail

- James P. Allen: Further Evidence for the Coregency of Amenhotep III and IV? In: Göttinger Miscellen No. 140, Göttingen 1994, pp. 7–8.

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Some remarks on the presumed coregence of Amenophis III. and IV. In: Göttinger Miszellen No. 83, Göttingen 1984, pp. 11-12.

- Christian Cannuyer: Akhet-Aton: Anti-Thèbes ou sanctuaire de globe? A propos d'une particularité amarnienne méconnue. In: Göttinger Miszellen No. 86, Göttingen 1985, pp. 7-12.

- Marianna Doresse: Observations on the publication des blocs des temples atoniens de Karnak: The Akhenaten Temple Project. In: Göttinger Miscellen No. 46, Göttingen 1981, pp. 45–79.

- Andreas Finger, Christian Huyeng: The object Berlin 14145. In: Isched. Journal of the Egypt Forum Berlin eV No. 02, 2010, Berlin 2010, pp. 5–15, ( PDF file; 136 kB ).

- Michael E. Habicht: Some reflections on the proposed 8-year co-regency of Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV Akhenaton. In: Göttinger Miscellen No. 241, Göttingen 2014, pp. 25–36.

- Erik Hornung : The New Kingdom. In: Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, David A. Warburton (eds.): Ancient Egyptian Chronology (= Handbook of Oriental studies. Section One. The Near and Middle East. Vol. 83). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2006, ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5 , pp. 197-217 ( online ).

- Friedrich Junge : A fragment of the head of an Achenaten statue from Elephantine. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 47, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, pp. 191-194

- Rolf Krauss : Kija - the original owner of the canopic jars from KV 55. In: Messages from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 42, von Zabern, Mainz 1986, pp. 67-80.

- Rolf Krauss: End of Nefertitis. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 53, von Zabern, Mainz 1997, pp. 209-219.

- Heinz Kreutz : Akhenaten as an artist or the triptych . Attempt to approach. Rimbaud, Aachen 2011 ISBN 978-3-89086-508-9

- Christian E. Loeben : A burial of the great royal wife Nefertiti in Amarna? : The dead figure of Nefertiti. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 42, von Zabern, Mainz 1986, pp. 99-107.

- Yahia el-Masry: New Evidence for Building Activity of Akhenaten in Akhmim. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 58, von Zabern, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-8053-2979-2 , pp. 391-398.

- Irmtraut Munro : Compilation of dating criteria for inscriptions from the Amarna period according to JJ Perepelkin “The Amenophis IV Revolution”, Part 1 (Russian), 1967. In: Göttinger Miszellen No. 94, Göttingen 1986, pp. 81–88.

- Peter Munro : Notes on two king sculptures from the Amarna period. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. No. 47, von Zabern, Mainz 1991, pp. 255-262.

- Jürgen Osing : On the Koregenz Amenhotep III - Amenhotep IV. In: Göttinger Miscellen No. 26, Göttingen 1977, pp. 53–54.

- Nicholas Reeves: Akhenaten after all? In: Göttinger Miscellen No. 54, Göttingen 1982, pp. 61–72.

- Nicholas Reeves: Tuthmosis IV as "Great-Grandfather" of Tutankhamun. In: Göttinger Miscellen No. 56, Göttingen 1982, pp. 65–70.

- Julia E. Samson: Akhenaten's coregent Ankhkheperure-Nefernefruaten. In: Göttinger Miscellen No. 53, Göttingen 1982, pp. 51–54.

- Julia E. Samson: Akhenaten's Successor. In: Göttinger Miscellen No. 32, Göttingen 1979, pp. 53-58.

Web links

- Stefanie Hardekopf: Amenophis IV. / Akhenaten. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (eds.): The scientific biblical lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff., Accessed on May 26, 2012.

- Information about Akhenaten in the catalog of the German National Library

- Information about Akhenaten in the German Digital Library

- Information about Akhenaten in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Jan Dönges: paternity test for a mummy. DNA examination on Tutankhamun provides new findings. Wissenschaft-online.de, February 16, 2010, accessed on March 27, 2011 .

- Akhenaten and Nefertiti

- Ancient Egypt

- amarna royal tombs project (English)

References and comments

- ↑ Sometimes referred to as the female king "daughter of ...".

- ↑ see 14th century BC Chr. , And Late Bronze time corresponds to the New Kingdom (about 1550 to 1070 v. Chr.)

- ^ Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , p. 66 .

- ^ Ludwig Morenz : The time of the regions in the mirror of the Gebelein region: cultural-historical reconstructions. Brill, Leiden 2010, ISBN 90-04-16766-8 , p. 27.

- ↑ a b A DNA analysis in 2010 confirmed the previous assumptions that Akhenaten was the father. In addition, Zahi Hawass found a matching counterpart in relief in 2008 . The inscription on the overall relief shows that Tutankhamun was Akhenaten's son as Tutanchaton and Ankhesenpaaton as daughter ( memorial from November 24, 2009 in the Internet Archive ); see. also Günther Roeder: King's son Tut-anchu-Aton. In: Rainer Hanke: Amarna reliefs from Hermopolis (excavations of the German Hermopolis expedition in Hermopolis 1929–1939), Vol. 2 . Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1969, p. 40.

- ↑ Gabriele Höber-Kamel: Under the rays of Aton - On the history of the Armana time. In: Kemet issue 1/2002 , p. 6.

- ↑ Michael E. Habicht: Nefertiti and Akhenaten. The secret of the Amarna mummies. P. 34.

- ^ Dieter Arnold : Lexicon of Egyptian architecture. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2000. ISBN 3-491-96001-0 .

- ^ Robert B. Partridge: Photo Feature, Colossal Statues of Akhenaten from the Temple of Karnak. In: Ancient Egypt. 43 Vol. 8, No. 1, August / September 2007, (www.ancientegyptmagazine.com)

- ↑ Explanation by Christian E. Loeben , Humboldt University Berlin, in: ZDF Expedition: Akhenaten and Nefertiti - The Heretic's Mummy. (Wednesday, August 23, 2006, 2:15 p.m.)

- ↑ Christine El Mahdy : Tutankhamun - Life and Death of the Young Pharaoh. Blessing, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-89667-072-7 .

- ^ Gerhard Krause: Theological Real Encyclopedia . Volume 27. 1997, ISBN 3-11-015435-8 , pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Built for the only god. In: Petra Vomberg, Spektrum der Wissenschaft Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. November 26, 2012, accessed July 25, 2019 .

- ↑ The Palaces of Achet-Aton. In: Frank Müller-Römer, University of Heidelberg, Grabengasse 1, 69117 Heidelberg. August 18, 2012, accessed July 25, 2019 .

- ↑ a b The year 12 of Akhenaten, transmission of events between media staging and sepulcral self-thematicization. In: Fitzenreiter, Martin, Humboldt University Berlin. 2009, accessed July 25, 2019 .

- ^ Hermann A. Schlögl: Akhenaten. Munich 2008, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Winfried Barta justifies his assumption with the heavenly coronation day on the second lunar day of the month . The coronation of the new king was automatically linked to this day in mythological terms. Based on Barta's information, Akhenaten could possibly rule from 1353 to 1336 BC. Chr .; according to Winfried Barta: accession to the throne and coronation ceremony as different testimonies to royal takeover. In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture (SAK) 8 . Buske, Hamburg 1980, p. 43.

- ↑ Stefanie Hardekopf: Amenophis IV. / Akhenaten (Section 7.2. The Restoration) . ( online [accessed October 19, 2018]).

- ↑ Athena Van der Perre: Nefertiti (for the time being) last documented mention. In: In the light of Amarna - 100 years of the discovery of Nefertiti . (Catalog for the Berlin exhibition, December 7, 2012 to April 13, 2013). Imhof, Petersberg 2012, pp. 195–197.

- ↑ Marc Gabolde : The end of the Amarna period. In: Alfred Grimm , Sylvia Schoske : The secret of the golden coffin. Akhenaten and the end of the Amarna period. (= Writings from the Egyptian Collection. [SAS] Vol. 10). Munich 2001, ISBN 3-87490-722-8 , p. 24.

- ^ CN Reeves: The Valley of the Kings , Kegan Paul, 1990, pp. 44-49

- ↑ Bell, 1990, p. 133

- ^ TM Davis: The Tomb of Queen Tiyi , KMT Communications. 1990, pv

- ^ A b c T. M. Davis: The Tomb of Queen Tiyi , KMT Communications, 1990, p.ix.

- ^ Cyril Aldred: Akhenaten, King of Egypt , Thames and Hudson, 1988, p. 201

- ↑ a b Cyril Aldred: Akhenaten, King of Egypt , Thames and Hudson, 1988, pp. 201-202

- ^ A b Zahi Hawass, Sahar Saleem: Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies . Ed .: Sue D'Auria. The American University at Cairo Press , Cairo; New York 2016, ISBN 978-977-416-673-0 , pp. 84, 86 .

- ↑ CN Reeves: Akhenaten, Egypt's False Prophet , Thames and Hudson, 2001, p. 84

- ^ Joann Fletcher: The Search for Nefertiti , William Morrow, 2004, p. 180

- ^ A b c d E. Strouhal: "Biological age of skeletonized mummy from Tomb KV 55 at Thebes" in Anthropology: International Journal of the Science of Man , Volume 48, Number 2, 2010, pp. 97-112

- ^ A b Zahi Hawass et al .: "Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family", The Journal of the American Medical Association, 2010, p. 644

- ↑ a b News from the Valley of the Kings: DNA Shows that KV55 Mummy Probably Not Akhenaten. Kv64.info, March 2, 2010, archived from the original on March 7, 2010 ; Retrieved August 25, 2012 .

- ↑ Nature 472, 404-406, 2011; On-line

- ↑ NewScientist.com; January 2011; Royal Rumpus over King Tutankhamun's Ancestry

- ↑ NewScientist.com; January 2011; Royal Rumpus over King Tutankhamun's Ancestry

- ↑ JAMA 2010; 303 (24): 2471-2475. "King Tutankhamun's Family and Demise"

- ↑ D. Bickerstaffe: The King is dead. How Long Lived the King? in Kmt vol 22, n 2, Summer 2010.

- ↑ Corinne Duhig: "The remains of Pharaoh Akhenaten are not yet identified: comments on 'Biological age of the skeletonized mummy from Tomb KV55 at Thebes (Egypt)' by Eugen Strouhal" in Anthropologie: International Journal of the Science of Man , Vol 48 Issue 2 (2010) pp. 113-115. (subscription) "It is essential that, whether the KV55 skeleton is that of Smenkhkare or some previously-unknown prince ... the assumption that the KV55 bones are those of Akhenaten be rejected before it becomes" received wisdom ".

- ↑ Who's the Real Tut? retrieved Nov 2012

- ^ N. Reeves: Akhenaten. Egypt's false prophet. Pp. 176-177.

- ^ Franz Maciejewski: Akhenaten. To correct a myth. Osborn, Berlin 2010, p. 24.

- ↑ Michael E. Habicht: Nefertiti and Akhenaten. The secret of the Amarna mummies. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 2011, pp. 18–24.

- ↑ Adolf Metzner: Hormonal disorders made the Pharaoh so ugly. In: The time. February 10, 1978, accessed July 18, 2020 .

- ↑ J. Assmann has dealt in detail with the Joseph novels and Thomas Mann's image of Egypt in: Thomas Mann and Egypt. Myth and monotheism in the Joseph novels. Beck, Munich 2006. See also Jan Assmann's theory of “cultural memory”

- ↑ Toe of Akhenaten back in Egypt ( Memento from July 27, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ). In: DLR Kultur , news from April 15, 2010.

- ↑ a b Erik Hornung: Akhenaten. The religion of light. Patmos 2003.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Amenhotep III |

Pharaoh of Egypt 18th Dynasty |

Semenchkare |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Akhenaten |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Amenhotep (IV.); Amenophis; Nefer-cheperu-re; Ah-an-Jati; Akenaten |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Pharaoh of ancient Egypt during the New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1351 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 1334 BC Chr. |