Kija (Egypt)

| Kija in hieroglyphics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kija Kjj3 |

|||||

|

Portrait of Kija made of quartzite (height 11 cm), Egyptian Museum Berlin (Altes Museum), inv. 21245 |

|||||

Kija was a concubine of the ancient Egyptian king ( pharaoh ) Akhenaten in the 18th Dynasty ( New Kingdom ). Her origin is unknown and it is mostly believed that she was a princess of foreign descent from the Mitanni Empire.

Name and origin

The short form of the name probably suggests a foreign name that was Egyptized. Based on this assumption, it is mostly assumed that she is identical with the Mitannian princess Taduchepa , who Akhenaten from the harem of his father Amenophis III. had taken over. Thomas Schneider speaks out against such an interpretation of the name. Kija does not necessarily have to have been this Mitanni princess, the daughter of King Tušratta , who was accompanied to the Egyptian court by around 317 other Mitanni women. Another possibility is that she came to Egypt in the wake of Princess Taduchepa.

The complete title of the Kija has been handed down:

| Full title of the kija in hieroglyphics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ḥm.t mrr.ty ˁ3.tn Nswt bjtj ˁnḫ m m3ˁ .t (Nfr-ḫpr.w-Rˁ-wˁ-n-Rˁ) p3 šrj nfr n p3 Jtn ˁnḫ ntj jw.f ˁnḫ r nḥḥ ḏ.t Kyj3 Beloved wife of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, who lives in Maat , With perfect forms of the Re, the only one of the Re , the good child of the living Aton, who lives forever and ever, Kija |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The titles of the kija seem a bit unusual overall. There are terms such as "wife", but also "great lover of the king of both countries" and "noble from Naharina ". The term ta schepset ("high woman"), which is found on inscriptions on vessels , is also associated with Kija . The assignment to Kija is not clear here, as the personal name is only partially preserved and cannot be reconstructed. According to Hermann A. Schlögl, it is questionable that Kija is this "high woman", as she is otherwise not handed down with this title.

supporting documents

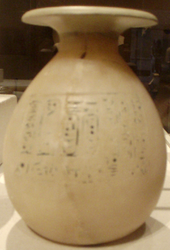

Erik Hornung states that Kija was briefly mentioned in scientific literature for the first time in 1959 and 1961 and that it became better known through further research by Jurij Perepelkin, Rainer Hanke, Wolfgang Helck and Rolf Krauss . Kija is documented by various finds from Akhenaten's newly founded capital Akhet-Aton , which bear her name or whose inscriptions can be added to the name of Kijas: make-up tubes, ointment vessels made of calcite and palimpsests with text fragments . The objects are now in museums in London ( British Museum ), New York ( Metropolitan Museum of Art ) and Berlin ( Egyptian Museum Berlin ).

In the course of the past few years, other representations were assigned to her that had previously been ascribed to other people from the Amarna period . Characteristic for representations of the Kija are the so-called Nubian wig (stepped curly wig) and large disc-shaped earrings.

Your life in Achet-Aton

Most of the documents clearly assigned to her come from Akhet-Aton, so that conclusions can be drawn about her life in Akhenaten's newly founded capital. However, the evidence is interpreted differently by Egyptology . The finds do not provide any information about the time at which Kijah came to Egypt and Akhet-aton.

Kija and Akhenaten

The fact that Kija came to the fore for some time at the royal court of Achet-Aton is undisputed. However, there are different views in Egyptology as to when this happened. The reasons why Akhenaten favored another woman besides Nefertiti are also unknown. Her prominent position and her simultaneous appearance to Nefertiti is evidenced by a fragmentary representation: Here she stands behind Akhenaten under the sun god Aton , Nefertiti and two of her daughters are lying on the floor in Proskynesis . Another assumption is that Kija only came to the fore after Nefertiti's death and is said to have tried to gain Nefertiti's position of power. Pictures of princesses had been reworked so that they now showed Kija. Her special position is confirmed not only by the fact that Kija Akhenaten was the “great beloved wife of the king”, but also by the fact that she had a palace in the south of the city and her own chapel (often referred to as a kiosk ) in the temple of Aton . Since Kija is always shown with only one daughter, she had at least one daughter with Akhenaten. It is not known in which year Akhenaten's Kija gave birth to her child or children.

Kija and Nefertiti

The common interpretation of the finds about Kija is that she and Akhenaten's great royal wife Nefertiti spent several years at the same time in Akhet-Aton. However, these findings say nothing about the relationship between the two women. Nevertheless, the two ladies can be clearly distinguished in their rank and importance at Akhenaten's court. Not only through their title, but also through their position and role. Nefertiti was Akhenaten's “ Great Royal Wife ”, whereas Kija had the unusual title “Great Beloved Wife of the King”, but is also referred to as “the Lady” or “High Lady”. Akhenaten thereby raised her above all other harem ladies, but, unlike Nefertiti, she received no religious duties. Another difference can be found in the spelling of the names of both queens. In contrast to Nefertiti's name, the kija is never written in a cartouche . According to Erik Hornung, Kija is never depicted with a crown and a royal uraeus snake . On the other hand, Kija is assigned a relief pad in the Brooklyn Museum in New York City on which she kisses her daughter. In this scene she wears a diadem with a royal uraeus.

Kija and Merit-Aton

According to Wolfgang Helck , Kija apparently initially led the government after Akhenaten's death. As a result, she would come into question as the unknown king widow Dahamunzu , who is said to have asked the Hittite king for a prince as king for Egypt. She was then ousted by the eldest princess Meritaton , who married Semenchkare . It is speculation that there were disputes between her and Meritaton over the throne .

Death or displacement?

Like Nefertiti, Kija disappeared from the Amarna records in Akhenaten's 12th year of reign, although there is also a date with her name from a later reign. What is certain is that her name was deleted from various text fragments and replaced by the names of two daughters of Akhenaten. In Maru-Aton there were palimpsests on which their name had been replaced by the Meritatons. On blocks from Amarna and built in Heliopolis , the so-called talatat , her name was replaced by that of Princess Meritaton as well as that of Princess Anchesenpaaton . The discovery that these are mentions of the Kija was of particular importance, as this name cancellation was previously seen as evidence that Nefertiti had fallen out of favor and had been cast out by Akhenaten.

Recent research

In 2007 the mummy of the younger lady (KV35YL) was removed from the grave of Amenhotep II ( KV35 ) by means of computer tomography by the radiologist Dr. Ashraf examined and found a highly likely identification as Kija. The type of mummification corresponds to that of a member of the royal house of the 18th dynasty. The mummy shows, among other things, a very large gaping wound in the cheek. Further examination of the head revealed evidence of a bruise in the area, which led to the conclusion that the injury was inflicted while she was still alive. In addition, there are remains of the shattered upper jaw and pieces of teeth deep in the paranasal sinuses . This finding suggests a violent death from a blow with a hard object. During the embalming that followed, the wound was cleaned and the hole was hidden under resin and filler material.

Otherwise the skull has several peculiarities. The posterior part of the skull is asymmetrical , underdeveloped on the left side and has an unusual process that looks like a small spur. A comparable anomaly is known only in Tutankhamun so far . The age of the woman at the time of death was estimated to be between 22 and 45 years. In addition, the birth of at least one child could be proven.

DNA analyzes from 2010 have now identified the mummy as Tutankhamun's mother and Amenhotep III's parents . and Queen Teje could be determined. As a result, it is unlikely that the mummy will be assigned to Kija, since its origin is unknown and it is not mentioned in any previously found inscription with the titles of a “king's daughter” or “king's sister”. According to the investigation, the mummy was both a sister and a wife of the mummy found in grave KV55 , which in all likelihood is Akhenaten's.

Connection to KV55

The following grave objects from the ominous grave KV55 in the Valley of the Kings could be assigned to Kija after detailed investigations: Canopic jars and the splendid gold-plated coffin, in which a male skeleton was located. Both the canopic jar and the coffin were reworked for the burial of this male person in KV55. During the last examination of the coffin in 2001 and the grave goods related to KV55, Alfred Grimm came to the following conclusion by comparing the inscriptions on Kija's titulature: “This long titulature of the Kija contains Akhenaten's coffin formula The perfect child of the living aten , of which applies : He will live now and forever until all eternity , which was then wrongly interpreted as a reference to Kija as the first owner of the coffin from KV55. "

literature

- Dorothea Arnold , James P. Allen, Lyn Green: The Royal Women of Amarna. Images of Beauty in Ancient Egypt. Metropolitan Museum of Art / Distribution: Harry N. Abrams, New York 1996, ISBN 0-87099-818-8 , pp. 14-15.

- Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3 , p. 155.

- Michael E. Habicht: Nefertiti and Akhenaten. The secret of the Amarna mummies. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 2011. ISBN 978-3-7338-0381-0 , pp. 159-166.

- Christian Jacq : Nefertiti and Akhenaten. A ruling couple in the shine of the sun. Rowohlt, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-499-60758-1 .

- Erik Hornung : Akhenaten. The religion of light. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2003, ISBN 3-491-69076-5 , pp. 116-118.

- Hermann A. Schlögl : Akhenaten - Tutankhamun. Harrasowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 3-447-03359-2 .

- Hermann A. Schlögl: Akhenaten. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56241-9 , pp. 86-89.

- Joyce Tyldesley : The Queens of Ancient Egypt. From the early dynasties to the death of Cleopatra. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 2008, ISBN 978-3-7338-0358-2 , pp. 135-136.

Web links

- ZDF June 3, 2007 The ladies from grave 35 ( Memento from July 3, 2007 in the web archive archive.today )

- Kija announcement dpa

- Information on the history of ancient Egypt

- Press release Dr. Zahi Hawass on the CT examinations of the mummies from KV35

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael E. Habicht: Nefertiti and Akhenaten. The secret of the Amarna mummies. P. 162.

- ↑ Hieroglyphic rendering and transcription correspond to the inscription on the vessel Metropolitan Museum of Arts, no. 20.2.11 . Drawing and transcription are included in: Herbert W. Fairman, Once Again the So-Called Coffin of Akhenaten , in: The Journal of Egyptian Archeology Vol 47 , 1961, pp. 28-30. Deviating spellings and shorter variants are discussed in, among others, C. Nicholas Reeves: New Light on Kiya from Texts in the British Museum , in: The Journal of Egyptian Archeology Vol. 74 , 1988, 91-101.

-

^ German translation: Wolfgang Helck, LÄ III , 422-424.

English translation: William J. Murnane: Texts from the Amarna Period in Egypt , p. 90 No. 45 (A). - ↑ Michael E. Habicht: Nefertiti and Akhenaten. The secret of the Amarna mummies. P. 162.

- ^ Hermann A. Schlögl: Akhenaten. P. 87.

- ↑ Erik Hornung: Akhenaten. The religion of light. P. 118.

- ↑ a b Hermann A. Schlögl: The ancient Egypt (= Beck'sche series. Bd. 2305, CH Beck knowledge). Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-48005-5 , p. 239.

- ↑ Erik Hornung: Akhenaten. The religion of light. P. 117.

- ^ Hermann A. Schlögl: Akhenaten. P. 89.

- ^ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Pharaoh of the Sun. Akhenaten - Nefertiti - Tutankhamen. Bulfinch Press / Little, Brown and Company, Boston 1999, ISBN 0-87846-470-0 , p. 92

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck, Eberhard Otto: Small Lexicon of Egyptology. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1956, p. 30.

- ↑ Nicholas Reeves: Akhenaten. Egypt's false prophet (= cultural history of the ancient world . Vol. 91). von Zabern, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-8053-2828-1 . P. 182.

- ↑ See also ZDF broadcast of June 3, 2007 Die Damen aus KV35

- ^ Z. Hawass et al .: Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family . In: the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) . 303, No. 7, February 2010, pp. 638-47. doi : 10.1001 / jama.2010.121 . PMID 20159872 .

- ^ Alfred Grimm, Sylvia Schoske: The secret of the golden coffin. Akhenaten and the end of the Amarna period. Munich 2001, p. 118.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kija |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Concubine of Pharaoh Akhenaten |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 14th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 14th century BC Chr. |