Dahamunzu affair

The Dahamunzu Affair was a political affair between the Ancient Egyptians and the Hittites at the end of the Egyptian 18th Dynasty or the Amarna Period (approx. 1330 BC). It is one of the most remarkable and controversial events in ancient oriental history.

When the Hittite great king Šuppiluliuma I invaded the Egyptian border area of Amka, the Egyptians got into a difficult situation because the Pharaoh had just died. In this situation, the childless king widow of Egypt wrote a letter to Šuppiluliuma I with the request for a son as husband, who should rule over Egypt. This incredible offer astonished Šuppiluliuma and he suspected an intrigue , but in the end he accepted the offer anyway. He sent his son Zannanza to Egypt. This died, however, with Šuppiluliuma suspected the murder by the Egyptians. In response, he launched a retaliatory strike. Prisoners from this campaign brought an epidemic - probably the plague - to Anatolia , which Šuppiluliuma also succumbed to.

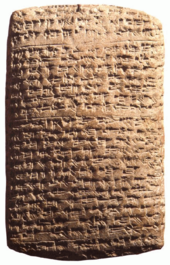

The matter has been handed down from the Hittite clay tablet archives of the Hittite capital Hattuša , especially in the “ Mannestaten Šuppiluliuma ”. These texts are written in cuneiform in the Hittite language . In addition, fragments of an original letter from the Egyptian queen in Akkadian language and the fragmentary draft of a reply from the Suppiluliuma to the news of Zannanza's death have been preserved.

The Egyptian queen is called Dahamunzu in cuneiform, a Hittite attempt to reproduce the Egyptian title t3-ḥm.t-nsw (ta-hemet-nesu - "the king's wife"). The late Egyptian king is portrayed as Nibhururia. The throne names of Tutankhamun ( Nb-ḫprw-Rˁ - Neb-cheperu-Ra) and Akhenaten ( Nfr-ḫprw-Rˁ - Nefer-cheperu-Ra) come into question. From a philological point of view, the identification with Tutankhamun is less problematic, but this results in chronological problems, which is why some researchers advocate Akhenaten. If one assumes the deceased Pharaoh Akhenaten, theoretically the widows Nefertiti , Kija and Meritaton are available for Dahamunzu , with Tutankhamun it is his widow Ankhesenamun .

Lore

Written sources

In the Central Anatolian highlands lie the ruins of Hattuša (near today's village of Boğazkale , formerly Boğazköy), the former capital of the Hittite Empire. There archaeologists discovered the clay tablet archives of the Hittite kings. Among them were the so-called " Mannestaten Šuppiluliumas " (often also called "Annals Šuppiluliumas"), which Mursili II. , A son and successor of the Hittite great king Šuppiluliuma I , wrote. Mursili described this in lively language and repeatedly added quotations from oral speeches, letters and messenger reports. Of interest here is the seventh panel of the work, a high-quality literary example of these annals, which passed down the so-called Dahamunzu affair. In addition, fragments of the original letter from the Dahamunzu have been preserved, as well as the fragmentary draft of a reply letter from Šuppiluliuma to the news of Zannanza's death. The original letter from the Dahamunzu is written in Akkadian , the language of diplomacy at the time. Two letters from the Dahamunzu and the Egyptian ambassador Hani are quoted in the Mannestatssuppiluliuma. On the one hand, these passages are certainly second-hand and, on the other hand, they could be translations into Hittite, since the original versions would be expected in Akkadian.

The historical starting point

At the end of the Amarna period , the Hittites, Mitanni and Egyptians fought for supremacy in what is now Syria . Aziru , the prince of the Amurru province , which had previously belonged to the Egyptian sphere of influence, went over to the Hittites and concluded a treaty with them.

Karkemiš was able to withstand a first campaign of Šuppiluliuma and remained an important base of the Mitanni. At the same time, the Egyptians tried to regain control of abandoned territories in the Middle East. Thus Egyptian troops moved to Kadesh , which had conquered Šuppiluliuma: The troops and chariots of Egypt came to Kinza (Kadesh), which my father (Šuppiluliuma I) had conquered. And Kinza attacked them.

A reaction was demanded from Šuppiluliuma, and at the same time he got into a two-front war. He sent troops to Kadesh and at the same time went to Karkemiš himself. During the siege of Karkemiš he sent the two generals Lupakki and Tarhunta-zalma to the land of Amka, an Egyptian border region. When the Egyptians found out about the conquest of Amka, they were terrified and in a difficult position because the Pharaoh had just died. In this situation the Hittite king received a letter from the childless king widow of Egypt with the request for a son as a future husband.

Letter from the Egyptian king's widow with a request for a son

In the annals of Šuppiluliuma it is described how he received a letter from the Egyptian king widow before the conquest of Karkemiš with the request for a son as husband, who was to rule over Egypt:

“And while my father (Šuppiluliuma I.) was down in Kargamiš, he sent the Lupakki and the Tarḫunta-zalma to the land of Amka. And they attacked the land of Amka and brought prisoners, cattle (and) sheep back to my father. When the people of Egypt heard of Amka's conquest, they were afraid. And because their master, the Pipurija, had just died for them, the queen of Egypt, who was the Daḫamunzu, sent a messenger to my father. And she wrote to him as follows: “My husband has died. But I don't have a son of my own. But you are said to have many sons. If you give me a son of yours, he shall become my husband. But I will never take one of my servants and make him my husband. I fear such a defilement ! ""

Fragments of the original of the letter quoted have also survived:

“[...] See, I am in the [state of] familylessness! [Send me a son of yours, and the two great countries will become] one country, and you will have me [brought your gifts and I will be glad about them]; and I will have my presents brought to you as well, and you will be happy about them [!] "

This unbelievable offer astonished Šuppiluliuma: “Such a thing has never happened to me!” He suspected a deception and carefully sent the eunuch Hattusa-zidi to Egypt to check the offer with the message: “To have a son of her master Maybe you. But they may be deceiving me, and they don't even want my son for the reign. ”Šuppiluliuma also had the archives researched for earlier Egyptian-Hittite relations. They brought him a contract in which the residents of Kurustama play an important role, which is why it is known as the Kurustama contract .

Another letter from the Queen and an interview with an Egyptian messenger

In the meantime, Šuppiluliuma was able to conquer Karkemiš, and after he had arranged the situation, he moved back to the land of Hatti. The following spring, Hattusa-zidi returned from Egypt, along with an Egyptian messenger named Hani, who presented another letter from the Egyptian queen:

“Why do you say,“ I could be deceived. ”If I had a son, I would have written to another country about my own and my country's shame. Who was my husband died. I don't have a son. I will never take a servant of mine and make him my husband. I have not written to any other country, (but) I have written to you. Your sons are numerous, they say. Give me a son of yours and he will become my husband, but in Egypt he will become king! "

After a gap in the tradition follows the description of a conversation with the messenger Hani:

““ [I (Šuppiluliuma) ...] have been kind, but you have done evil to [me]. You came and attacked the prince of Kinza (Kadesch) whom I took from the king of the Hurriterland. When I heard about it, I became angry, and I sent my troops, my chariots, gentlemen, and they attacked your [border], the land of Amka. And when they attacked your [land of Amk], you were afraid [of many things] and therefore asked me for a son as a gift. [This] but he will possibly become a hostage, [and you will not make him king. "[The following] Ḫani said to my father:" My lord! This [...] shame on our country. If we really had any [a prince], would we have come to another country and keep asking for a lord for us? Who was our Lord, Nipḫurija, died. Our Lord's wife is childless. We ask a son (of you), our Lord, for the kingdom of Egypt. For the wife, our mistress, as her husband, we ask him! Otherwise we did not go to any other country, (we only) came here! Our Lord, give us your son. ""

Zannanza's death and Suppiluliuma's reaction

Suppiluliuma finally gave in to the wishes of the Egyptian king's widow and chose a son. He drew up a treaty that was supposed to regulate the friendly relations between Egypt and Hatti. The poorly preserved panel KUB 19.4 shows that he sent his son Zannanza to Egypt, but that he was possibly murdered. At least in the Šuppiluliuma annals it is reported that some people said "They killed [Zannanza]" and brought the news "Zannanza [died]".

At least the fragmentary draft of a letter from Šuppiluliuma, which is to be regarded as a reaction to the official report from the Egyptian side, is reproduced here in extracts:

"[...] [As for the fact that you wrote [to me]:" Your son died, [but I by no means treated him] [badly] ", [...] [to the Seated on the throne] you could have sent my son home! [...] you may have murdered my son! [...] For me the weather god is my lord, [king of the countries, [and] the sun goddess of Ar] inna, my lady, the queen of the countries: they will come (and) this [case will be the weather god, mine Lord] and the sun goddess of Arinna , my mistress, decide. [What] s [that you call your troops] so numerous over and over again, so much [...] [so big] ss will not be for you [your army.] What [is] it (what) we do ? [...] Because a hawk will not drive away a single chick [...] the [hawk by itself! [...] "

A retaliatory strike from Šuppiluliuma was the expected reaction, since Egyptian-Hittite relations had deteriorated significantly with the attack on Amka even before the Dahamunzu affair. The Crown Prince Arnuwanda crossed the Egyptian border and made thousands of prisoners of war. Unfortunately, they brought the plague into Anatolia, from which Šuppiluliuma also died.

Philological remarks

Dahamunzu

The name of the Egyptian queen is not known. The expression "Dahamunzu", which has long been understood as an Egyptian proper name, is nothing more than a Hittite attempt to reproduce the Egyptian t3-ḥm.t-nsw (ta-hemet-nesu - "the king's wife"). Obviously the Hittites had misunderstood a title as a name.

Nibhururia and Bibhururia

The interpretation of the king's name also causes certain difficulties. The king is known as Bibhururia (KBo V, 6, III, 7) and Nibhururia (KBo XIV, 12, IV, 18). From the historical context, the following kings come into question:

- Amenophis IV./ Akhenaten , approx. 1351-1334 BC Chr., Throne name: Nfr-ḫprw-Rˁ (Nefer-cheperu-Ra), "With perfect figures, a Re"

- Semenchkare , approx. 1337-1333 BC Chr., Throne name: ˁnḫ-ḫprw-Rˁ (Anch-cheperu-Ra), "With living figures, a Re"

- Tutankhamun , approx. 1333-1323 BC Chr., Throne name: Nb-ḫprw-Rˁ (Neb-cheperu-Ra), "Lord of shapes, a Re"

- Eje , approx. 1323-1319 BC Chr., Throne name: Ḫpr-ḫprw-Rˁ (Cheper-cheperu-Ra), "The one shaped in form, a Re"

Bibhururia is definitely flawed because of the Bib- element, so any name can be mutilated here. In addition, the two variants are to be assessed paleographically differently. The second variant is younger and offers the correct transcription. This means that Bibhururia does not gain any weight. The Bibhururia Hittite scribe made a mistake when copying from an older version by confusing two similar looking characters. From a philological point of view, Akhenaten and Tutankhamun are shortlisted, since the cuneiform element Nib- can only be equated with Egyptian Nfr - or Nb -, as can be found in the throne names of these two kings.

Does Nib stand for Nfr or Nb in Egyptian?

It is easy to equate Nib-huru-ria with Tutankhamun's throne name Nb-ḫprw-R : The throne name of Amenhotep III. is Nb-m3ˁt-Rˁ (Neb-Maat-Re) and corresponds to the cuneiform Nib-mua-ria. This gives the equation Egyptian nb (neb) = cuneiform nip. Akhenaten's throne name Nfr-ḫprw-Rˁ is well documented in cuneiform as Nap-hurur-ria, so in Egyptian nfr (nefer) at the time of Akhenaten is usually rendered with cuneiform nap. The question is whether Nibhururia could also be a cuneiform variant of Naphururia, or, in other words, whether cuneiform Nib can also stand for Egyptian Nfr. Rolf Krauss answered this question in the affirmative, with the following considerations:

- the r of nfr had fallen silent, leaving the consonants nf and the word spoken as naf.

- nfr / naf was usually written in cuneiform nap because cuneiform script p writes for f. (Compare Nap-huru-ria = Nfr-ḫprw-Rˁ )

- The question arises as to whether nfr could be represented by nef as well as naf- as early as the Amarna period. Krauss relies here on an unpublished statement by Gerhard Fecht , according to which “under certain conditions that are given for the Šuppiluliuma annals, the toning down from naf to nef is to be set for the Amarna period”.

- As a transcription of nef- ni-ip is to be expected. (p for f; for the syllable characters containing * i, the corresponding e-containing symbols are also used.)

- Practically only one syllable character is used for ib / ip. This means that the cuneiform transcriptions cannot be distinguished from detoned nfr (= nef) and nb .

- From a philological point of view, it is therefore open whether Niphururia is to be equated with Nfr-ḫprw-Rˁ or Nb-ḫprw-Rˁ .

Winfried Barta , on the other hand, maintains that even if a detoning from naf- to nef- (for nfr ) could have already taken place in the Amarna period , the cuneiform Nibhururia corresponds better and more easily with Nfr-ḫprw-Rˁ . Most recently, Trevor R. Bryce said that Nibhururia was a precise cuneiform rendering of Tutankhamun's throne name, since the cuneiform nib / p could only be a transcription of Egyptian nb , but not of nf (r) . The name of the Nefertari from the 19th dynasty also speaks against a detoning in the Amarna period . Her name Nfr.t-jr.j (Neferet-iri) was rendered in cuneiform Naptera (Na-ap-te-ra) (and was pronounced Naftera accordingly). The equation nfr = nap also applies here .

In addition to the well-documented reproduction of Akhenaten's throne name as Naphuria, another variant is discussed in the Amarna letter EA 9. In this a king name Nibhuruia is handed down. According to William Moran, it is either the throne name of Tutankhamun or a variant of Naphururia. Hess and Krauss now wanted to strike all spellings under the argument of toning down nfr Akhenaten. However, the view that all graphs similar to Nibhuruia should be ascribed to Akhenaten has met with fierce opposition. In addition, a standardized pronunciation of the Egyptian king names in the Amarna letters can be assumed, which was necessary to avoid confusion.

Historical and chronological notes

The attacks on Amka and Kadesh

The chronological classification of the Hittite campaign in the land of Amka is difficult, especially in connection with the Amarna letters from the province of Amurru. Probably in the late reign of Akhenaten, a brother of Azirus sent the letter EA 170 to him. Aziru was in Egypt at this time. The letter describes similar events as in the Šuppiluliuma annals:

“In addition, Hatti's troops under Lupakku have captured cities of Amqu, and with the cities they captured Aaddumi. May our Lord know this. "

It makes sense to equate the actions of the Hittites known from various sources. Although chronological classification in the time of Akhenaten or shortly thereafter is obvious, equating the two actions is not mandatory and the chronological classification is ultimately questionable, because the relative and absolute chronology of the Amarna letters still causes great difficulties for research. Almost all letters were undated and only a few were addressed by name.

Marc Gabolde also tried to reconstruct the various reports of the vassals in the Amarna letters that they followed the king's instructions regarding the formation of troops in such a way that they show the troop movements of Akhenaten's campaign against Kadesh. Accordingly, the historical situation of the Dahamunzu affair corresponds to the situation at the end of Akhenaten's reign.

However, there are objections to this reconstruction: It is not clear whether the preparations or the campaign can really be attributed to Akhenaten. None of the vassals names the king. The preparations mentioned do not have to relate to a single event. This is evident in the mobilization of archers mentioned in EA 367, which must refer to an earlier incident.

EA 162 provides a further reference to the campaign, in which Aziru is rebuked for making common cause with the prince of Kadesh, although the Pharaoh is fighting against him. This remark (without mentioning a victory) and the lack of mentions of the other princes suggest that the campaign was a defeat. The mention of an unsuccessful campaign in Tutankhamun's restoration stele could also be in this context.

The role of the Egyptian queen

Closely related to the question of the identity of the deceased king is that of the Dahamunzu and their historical and political role. Assuming the deceased Pharaoh Akhenaten, theoretically the widows Nefertiti , Kija and Meritaton come into question, with Tutankhamun it is the widow Ankhesenamun.

For Kenneth A. Kitchen, Nefertiti was not in the position to write to Šuppiluliuma: In Semenchkare there was already an heir to the throne and there is no evidence that Nefertiti was in opposition to Semenchkare or that she would still be in opposition to Semenchkare after her husband's death was alive. In addition, she had no reason to marry a "servant" as long as Tutankhamun was the pretender to the throne. With the elevated position of Meritaton and later Ankhesenamun, Nefertiti was no longer in a position to elevate someone to king by marriage.

At the end of the Amarna period, after Akhenaten's death, the reign of a woman with the feminine throne name ˁnḫ.t-ḫpr.w-Rˁ is epigraphically and archaeologically secured. In addition, the Manethon tradition at the end of the 18th dynasty knows the government of a king's daughter with the throne name Akencheres a. which can be derived from ˁnḫ.t-ḫpr.w-Rˁ . Thus, according to Rolf Krauss, after Akhenaten, there must have been a single ruling princess with this throne name, who is to be equated with Meritaton, Akhenaten's eldest daughter-wife and later wife of Semenchkare. Semenchkare came to government by marrying the ruling Queen Meritaton and took his wife's throne name in grammatically masculine form (ˁnḫ-ḫpr.w-Rˁ) . To make such a demand, the queen must have played a high political role, the status of regent. Nibhururia's widow also conducted the intergovernmental negotiations under sole responsibility: "Neither beside her, nor above her, is a man to be recognized who exercised government control."

In a modification of Rolf Krauss, Marc Gabolde interprets the events as follows: The interim regent Meritaton asks Šuppiluliuma for a son. He sends Zannanza, who then also ascends the Egyptian throne as Semenchkare. After his assassination, his previous royal consort Meritaton takes over the government and the throne name Semenchkares and calls herself by birth name Nefer-neferu-Re.

Marc Gabolde's view met with strong resistance in research. In fact, there is no document confirming that Zannanza died on his journey to Egypt, although it is true that Suppiluliuma was informed of the death of his son by the Egyptian court. Nibhuruia died in autumn, while Šuppiluliuma did not send Zannanza until after winter, after which the latter came to Egypt around the following summer or autumn. Accordingly, Meritaton would have ruled as sole regent for a year. This contradicts a graffito in the grave of Pere with a year 3 of the Anchcheperure Neferneferuaton. If this king were identified with Meritaton, she would have ruled for three years, not one. If Zannanza / Semenchkare was murdered by anti-Hittite parties, it makes no sense that Meritaton did not lose her position. In addition, in the Hittite annals the fact that a Hittite ruled Egypt would have been discussed.

The fact that Tutankhamun died without a successor fits with Ankhesenamun as Tutankhamun's widow, with the statement by the Dahamunzu that they have no successor son. The statement that she would not marry a servant also fits into the picture of this time, since the real power was exercised by Eje and / or Haremhab, who were not directly related to the royal family.

The end of the Amarna correspondence

If one identifies Nibhuruia of the Amarna letter EA 9 with Tutankhamun, the question arises as to the end of the Amarna correspondence. The decisive question is whether Tutankhamun still received letters in Amarna or whether the text corpus ends earlier. This question is generally related to the chronological difficulties at the end of the Amarna period.

Already under Semenchkare the restoration of the old, pre-Amarna period conditions and a compromise restoration of the Amun cult began. Tutankhamun also initially continued this “gentle” return to the old faith. At some point he introduced a more uncompromising restoration by changing his name from Tutankhaton to Tutankhamun and giving up the residence in Amarna in favor of Memphis. This begs the question of when Tutankhamun left Amarna. According to Erik Hornung, "Aton and his high priest still play an important role in the vessel inscriptions of the 2nd year of reign". Rolf Krauss, on the other hand, assumes that Amarna was probably left in Tutankhamun's first year:

“In any case, the city was given up between the grape harvests of Tutankhamun's 1st and 2nd year, as there are wine jar seals from the 1st year, but no seals from the 2nd year from Amarna. The date year [1], which is probably to be added to the restoration stele of Tutankhamun, speaks in favor of leaving the city after the 1st grape harvest [...]. "

Edward Fay Campbell thinks it is possible that Tutankhamun still received letters EA 9, 210 and 170 in Amarna, but that they were sent there rather “by mistake”. The assumption that Tutankhamun is the addressee of EA 9 leads, according to Hornung, to conclusions that are so improbable that the equation of Nibhuruia with Akhenaten cannot be rashly ruled out. He also assumes that only those letters were left in Amarna that were no longer up-to-date when the residence was moved. According to Hornung, this all indicates that the Amarna archive will end soon after Akhenaten's 12th year of reign, before or at the beginning of Semenchkare's co-government.

Transitional period of the succession of Tutankhamun

According to Gabolde, the transition period of Tutankhamun's succession by Eje does not allow any correspondence with Tutankhamun's widow. Eje immediately succeeded Tutankhamun on the throne, as evidenced by the fact that Tutankhamun carried out his funeral, which should have taken place 70 days after Tutankhamun's death.

The time problem with the accession to the throne was solved in different ways: Eje could have agreed to negotiations between the Ankhesenamun and the Hittites. Accordingly, he saw his government as limited in time, "because Hattusa-ziti had officially traveled to Egypt, but then did not report in Hatti about the kingship of Eje". Erik Hornung concludes from the course of events (based on the equation of Nibhururias with Tutankhamun) "that the Egyptian royal throne remained vacant for a few months after the probably surprising death of the young Tutankhamun." Eje the throne.

Against this one can object: If Eje had been a “placeholder” for Zannanza, he would certainly have had his say in the negotiations. The fact that Šuppiluliuma agreed to the offer seems incompatible with the existence of an Egyptian king. Tutankhamun's funeral must have taken place between mid-March and the end of April. This follows from the plants blooming at this time, the flowers and fruits of which were found in the grave as gifts. Within this interval they are to be dated as late as possible because of their seasonal cohesion. If, in addition to the 70-day mourning period, one calculates the transfer time of the mummy from Memphis to Thebes (if Tutankhamun actually died in Memphis), one obtains "a difference of about three months between Tutankhamun's death and burial". Accordingly, Tutankhamun would have died in January. The arrival of the king's widow's letter is to be dated in early autumn. The siege of the city of Karkemiš lasted about a week. Then Šuppiluliuma moved into his winter quarters: "That had to happen early, if possible before the mountain rivers flooded due to the rain that started in October, making them difficult for an army to pass, or even snowfalls made it impossible to cross the Taurus passes." Messenger is to be set at three weeks. Thus Tutankhamun's funeral would have taken place with a delay of six months. However, according to a new calculation of the travel times, the negotiations can hardly have taken place after Tutankhamun's death, since a new ruler was certainly enthroned due to the length of the distance to be covered and the number of days required for this.

Equating Hittite Arma'a with Haremhab

Jared L. Miller succeeded in re-tapping a source by amalgamating seven fragments (KUB 19.15 + KBo 50.24). It is a historical-narrative text that refers to events in the reign of Muršilis II and names an Arma'a as his Egyptian opponent. According to Miller, the event dates back to Mursili's seventh and ninth year of government. Ruggerio Stefanini already identified Arma'a on the well-known fragment KUB 19.15 with haremhab and Miller's arrangement seems to support this thesis.

The reconstructed text speaks of Tette von Nuḫašše , who defected from the Hittites to the Egyptians. Muršili II protested at Arma'a and demanded that Tette be extradited. In a second part an attack by Arma'a on Amurru is reported, which was repulsed by the Hittites.

Taking into account the traditions of Haremhab's name by Manetho as Armais (Eusebius), Harmais (Josephus), Armesis (Africanus) and Armaios (Josephus), the equation with Arma'a is possible, due to the context even very likely, but not completely certain.

Of decisive importance for the chronological classification and the question of Nibhururia's identity is the question of whether Arma'a (haremhab) was already Pharaoh at the time of these events.

Miller denies this. He assumes that Arma'as (haremhabs) status in the text was not that of Pharaoh, but that of Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Army, with the following considerations:

- Muršili never describes Arma'a as a king (LUGAL or even LUGAL.GAL = great king), as the Hittite kings normally do in correspondence with other kings during this period.

- Arma'a represents the birth name Ḥr-m-ḥb (Hor-em-heb - Haremhab) and not the later throne name Ḏsr-ḫprw-Rˁ (Djeser-cheperu-Re).

- Haremhab's military activity took place mainly under the rule of his predecessors, especially Tutankhamun.

Under this condition, Haremhab would not have ascended the Egyptian throne until after Mursili's ninth year of reign. Tutankhamun's death would thus also fall during the reign of Muršili and Tutankhamun would not be identical with the pharaoh, who died in the late reign of Šuppiluliuma, but only Akhenaten would be eligible.

The assumption that it is General Haremhab and not Pharaoh Haremhab is not uncontested:

- The Hittite great king apparently calls the man of Egypt , which is possibly a derogatory term. So it is not surprising that the title of king is not mentioned.

- As this is an abbreviated quotation, no titles are to be expected.

- Since Haremhab in Hattuša was already known by his maiden name from his time as Commander in Chief of the Egyptian Army, it does not mean much that his throne name is not mentioned.

- In the cuneiform versions of the Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty , the birth name is always given, while the Egyptian texts mention the name of the throne.

- When it comes to important issues, as in the case of Nuhašše and Amurru, it is difficult to imagine that the Hittite great king would correspond with a general. Even if Haremhab was de facto the military ruler in Tutankhamun's time , one would certainly have turned to the ruling ruler.

Further individual questions

Why did Šuppiluliuma distrust the offer of the Dahamunzu?

Suppiluliuma reacted with great suspicion to the offer of the Dahamunzu and even went so far as to severely snub the Egyptian queen. According to Francis Breyer, caution is insufficient as an explanation. After all, Šuppiluliuma could have secured rule over the richest country of the time without military intervention. Breyer sees the family relationships at the Egyptian court as a possible reason, where sibling marriage was widespread. The Hittites, on the other hand, regarded incest as a reprehensible crime that even carried the death penalty . Incest was therefore seen as one of the most terrible crimes at the time of Šuppiluliuma: “Against this background, it is surprising to me. E. not if Suppiluliuma met an Egyptian queen, about whom he probably didn't know much more than that she was married to her brother, with extreme suspicion, even with disgust. "

Zannanza's death

Šuppiluliuma chose his son Zannanza as the future pharaoh. Vandersleyen doubted whether the prince who was sent to Egypt was really identical to the chosen Zannanza. However, there is little doubt about that. The prince's departure and possibly his passage through Amurru is described in the letter KUB III, 60 (CTH 216). The details of his death are not known. The “Mannestaten Šuppiluliuma” only describe the news of Zannanza's death (CTH 40, fragment 31). The plague prayers add up the events (CTH 378f.). Here the passage was understood quite differently. Goetze translated them with “They killed him as they led him there” ( i.e. they killed him when they brought him there ) Lebrun, on the other hand, in a completely different sense with “ils l'emmenèrent et le tuèrent” (i.e. they took him and killed him ). In the draft of a Hittite reaction to the official report of the Egyptians, Šuppiluliuma believes in a murder by the Egyptians, although they deny any guilt (CTH 154 = KUB XIX, 20 + CTH 832). Klengel thought it was possible that Zannanza had died of the plague . Against this is the fact that this fact would certainly have been mentioned in the plague prayers and that the Hittite reaction would not have been so violent. There is still no evidence of the attack on Zannanza's travel group, which is often alleged in the literature, and his death on the way to Egypt. It is possible that Zannanza was imprisoned in Egypt for a time, as suggested by Suppiluliuma I in his letters.

At the time of Tutankhamun, Haremhab was the commander-in-chief of the Egyptian army and, together with Eje, actually led the fate of the country for the growing king. Francis Breyer therefore believes it is possible that Haremhab and / or Eje were behind the murder of Zannanza. Whether they ruled by mutual agreement or Eje was a usurper remains to be seen. There is evidence of a connection between Eje and the widow Ankhesenamun. The two names stand together on a ring, which would suggest a common government. For Breyer, it was also Eje who justified himself to Šuppiluliuma. He sees a possible indirect assignment of guilt in the picture of the falcon tearing a chick: “Now the Hittites should have known what the name Haremhabs means or at least that its first component is the god's name Horus , and he is known to be a falcon god! "

The portrayal of the Hittites as "hungry" and "living like game in the desert" in General Haremhab's grave is also exemplary of the increasing hostility in Egyptian-Hittite relations. Francis Breyer says: "Even if the exact circumstances of the Zannanza affair are not known, it is not absurd to seek the starting point of the forces that probably actively thwarted Hittite interference in Egypt in Haremhab's environment."

The plague in Asia

The outbreak of a devastating epidemic in the Middle East and Asia Minor prevented “a huge expansion of the Hittites in the direction of Palestine.” In any case, the Hittite expansion efforts initially came to an end. It is not clear what disease it was, perhaps the "Syrian plague ". Šuppiluliuma I also fell victim to this disease. Muršili II asks the gods in the so-called “ plague prayers ” to put an end to the misery. As the cause he saw the wrath of the gods, especially the revenge for a fratricide that Šuppiluliuma committed before his accession to the throne of the designated successor Tudhalija II . Another cause is the breach of the Kurustama Treaty , which the Hittites committed when they invaded the Egyptian Amka plain.

This plague is likely to have plagued the entire Middle East and Asia Minor. Rib-Hadda of Byblos already reported the outbreak of an epidemic in the Amarna letters; the outbreak in Alašija ( Cyprus ) and Babylon has been handed down from other letters . How this disease, which lasted at least 20 years, is not entirely clear. The Hittites claimed that the Egyptian prisoners brought them in. There are no reports from Egypt itself. Perhaps the prisoners in Syria became infected, perhaps the late outbreak of the disease in Hatti suggests that it was carried off by the trade caravans.

literature

Translations and editions of the texts from Bogazköy

- Cuneiform texts from Boghazköi. (KBo) Leipzig et al., 1916 ff., ZDB -ID 130809-9 .

- Cuneiform documents from Boghazköi. (KUB) Berlin, 1921 ff., ZDB -ID 1307957-8 .

- Emil Forrer (Ed.): The Boghazköi texts in transcription. Volume 2: Historical texts from Boghazköi (= scientific publications of the German Orient Society. Vol. 42, ISSN 0342-4464 ). Hinrichs, Leipzig 1926.

- Eugène Cavaignac : Les Annales de Subbiluliuma. Heitz, Strasbourg 1931.

- Hans Gustav Güterbock : The Deeds of Suppiluliuma as Told by his Son, Mursili II. In: Journal of Cuneiform Studies . Vol. 10, No. 2, 1956, pp. 41-68; Vol. 10, No. 3, 1956, pp. 75-98, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1956, pp. 107-130.

- Elmar Edel (ed.): The Egyptian-Hittite correspondence from Boghazköi in Babylonian and Hittite language (= treatises of the Rhenish-Westphalian Academy of Sciences. Vol. 77, 1-2). 2 volumes (Vol. 1: Transcriptions and translations. Vol. 2: Commentary. ). Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1994, ISBN 3-531-05091-5 .

- Jörg Klinger : Inscriptions on the rulers and other documents on the political history of the Hittite Empire. Chapter 3: The report of the facts of Suppiluliuma I. - Excerpt. In: Texts from the environment of the Old Testament . New series, volume 2: State treaties, rulers' inscriptions and other documents on political history. Gütersloher Verlags-Haus, Gütersloh 2005, ISBN 3-579-05288-8 , pp. 147–150.

- Theo PJ van den Hout: The falcon and the chick: the new pharaoh and the Hittite prince? In: Journal for Assyriology and Near Eastern Archeology . Vol. 84, 1994, pp. 60-88, doi : 10.1515 / zava.1994.84.1.60 .

Individual questions

- Elmar Edel: New cuneiform transcriptions of Egyptian names from the Boǧazköy texts. In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies Vol. 7, 1948, pp. 11-24.

- Nicholas Reeves : Akhenaten after all? In: Göttinger Miscellen. Vol. 54, 1982, pp. 61-71.

- Winfried Barta : Akencheres and the widow of Nibḫuria. In: Göttinger Miscellen . Vol. 62, 1983, pp. 15-21.

- Trevor R. Bryce : The Death of Niphururiya and its Aftermath. In: The Journal of Egyptian Archeology. Vol. 76, 1990, ISSN 0075-4234 , pp. 97-105.

- Monika Sadowska: Semenkhkare and Zananza. In: Göttinger Miscellen. Vol. 175, 2000, pp. 73-77.

- Jared L. Miller: Amarna Age Chronology and the Identity of Nibḫururiya In the Light of a Newly Reconstructed Hittite Text. In: Altorientalische Forschungen 34, 2007/2, pp. 252–293. ( Online )

- Gernot Wilhelm: Muršilis II. Conflict with Egypt and Haremhabs accession to the throne. In: Die Welt des Orients Vol. 39, 2009, pp. 108–116.

- Christoffer Theis: The letter from Queen Daḫamunzu to the Hittite King Šuppiluliuma I in the light of travel speeds and the passage of time, in: Thomas R. Kämmerer (Ed.): Identities and Societies in the Ancient East-Mediterranean Regions. Comparative approaches. Henning Graf Reventlow Memorial Volume (= AAMO 1, AOAT 390/1). Münster 2011, pp. 301–331.

Relations between Egypt and the Middle East and Asia Minor

- Wolfgang Helck : The relations of Egypt to the Middle East in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC BC (= Egyptological treatises. Vol. 5). 2nd, improved edition. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1971, ISBN 3-447-01298-6 .

- Horst Klengel : Hattuschili and Ramses. Hittites and Egyptians - their long way to peace (= cultural history of the ancient world . Vol. 95). von Zabern, Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-8053-2917-2 .

- Francis Breyer : Egypt and Anatolia. Political, cultural and linguistic contacts between the Nile Valley and Asia Minor in the 2nd millennium BC Chr. (= Austrian Academy of Sciences. Memoranda of the overall academy. Vol. 63 = Contributions to the Chronology of the Eastern Mediterranean. Vol. 25). Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-7001-6593-4 .

Amarna letters and Amarna time

- Jørgen Alexander Knudtzon (Ed.): The El-Amarna-Tafeln. With introduction and explanations. Volume 1: The texts (= Vorderasiatische Bibliothek. Vol. 2, 1, ZDB -ID 536309-3 ). Hinrichs, Leipzig 1915.

- Rolf Krauss : The end of the Amarna era. Contributions to the history and chronology of the New Kingdom (= Hildesheim Egyptological contributions. Vol. 7). Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1978, ISBN 3-8067-8036-6 .

- William L. Moran (Ed.): The Amarna letters. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD et al. 1992, ISBN 0-8018-4251-4 .

- Marc Gabolde: D'Akhenaton à Toutânkhamon. (= Collection de l'Institut d'Archéologie et d'Histoire de l'Antiquité, Université Lumière-Lyon 2nd vol. 3). De Boccard et al., Paris et al. 1998, ISBN 2-911971-02-7 .

Chronology of the Egyptian New Kingdom

- Erik Hornung : Studies on the chronology and history of the New Kingdom (= Egyptological treatises. Vol. 11, ISSN 1614-6379 ). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1964.

- Kenneth A. Kitchen : Further Notes on New Kingdom Chronology and History. In: Chronique d'Égypte. (CdE). Vol. 43, 1968, ISSN 0009-6067 , pp. 313-324.

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Chronology of the pharaonic Egypt. The timing of Egyptian history from prehistoric times to 332 BC BC (= Munich Egyptological Studies. Vol. 46). von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 .

Web links

- Silvin Košak: Concordance of the Hittite cuneiform tablets. In: Hittitologie Portal Mainz, University of Würzburg with an online database of cuneiform texts

- reshafim.org: The "Zannanza affair".

Individual evidence

- ^ Francis Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. Political, cultural and linguistic contacts between the Nile Valley and Asia Minor in the 2nd millennium BC Chr. Vienna 2010, p. 171.

- ↑ Uniform edition, transcription and translation: Hans Gustav Güterbock: The Deeds of Suppiluliuma as Told by his Son, Mursili II. In: Journal of Cuneiform Studies . No. 10, 1956, pp. 41-130.

- ^ Related German translation: Jörg Klinger: Rulers' inscriptions and other documents on the political history of the Hittite Empire. Chapter 3: The report of the Šuppiluliuma I. - Excerpt. In: Texts from the environment of the Old Testament. New episode. Volume 2. State treaties, rulers' inscriptions and other documents on political history. Gütersloh 2005, pp. 147–150.

- ^ Elmar Edel: The Egyptian-Hittite correspondence from Boghazköy. Volume I, Opladen, 1994, No. 1, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Theo PJ van den Hout: The falcon and the chicken: the new pharaoh and the Hittite prince? In: Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 84, 1994, pp. 64-70.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. Pp. 402-403.

- ↑ Klinger: rulers' inscriptions. In: TUAT NF Vol. 2, p. 148.

- ↑ Klinger: rulers' inscriptions. In: TUAT NF Vol. 2, pp. 148-149.

- ^ Noble: The Egyptian-Hittite Correspondence IS 15.

- ↑ a b Klinger: rulers' inscriptions. In: TUAT NF Vol. 2, p. 149.

- ↑ a b Klinger: rulers' inscriptions. In: TUAT NF Vol. 2, p. 150.

- ↑ van den Hout: The falcon and the chicken. In: Zeitschrift für Assyriologie 84, 1994, p. 82.

- ↑ van den Hout: The falcon and the chicken. In: Journal of Assyriology. 84, 1994, pp. 68ff.

- ↑ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia p. 196.

- ↑ Walter Federn: Dahamunzu (= KBo V 6 III 8 ). In: Journal of Cuneiform Studies No. 14, 1960, p. 33.

- ^ Government data according to Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronology of Pharaonic Egypt. The calendar of Egyptian history from prehistoric times to 332 BC Chr. Mainz 1997. Transcription of the throne names : Rainer Hannig: Grosses Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German (2800-950 BC). The language of the pharaohs. Mainz 2000. Translation of the throne names: Thomas Schneider: Lexikon der Pharaonen. Düsseldorf 2002.

- ↑ Elmar Edel: New cuneiform transcriptions of Egyptian names from the Boghazköi texts. In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies 7, 1948, p. 15.

- ↑ Christoffer Theis: The letter of Queen Daḫamunzu to the Hittite King Šuppiluliuma I in the light of travel speeds and the passage of time, in: Thomas R. Kämmerer (Ed.): Identities and Societies in the Ancient East-Mediterranean Regions. Comparative approaches. Henning Graf Reventlow Memorial Volume (= AAMO 1, AOAT 390/1). Münster 2011, p. 305 and Breyer: Egypt and Anatolien. P. 175.

- ↑ This can also be derived from the title ni-ib ta-a-ua = nb-t3.wj (nebet-taui - "Lord of the two countries").

- ^ Noble: New cuneiform descriptions. P. 15.

- ↑ Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. P. 11.

- ↑ Winfried Barta: Akencheres and the widow of Nibḫururia. In: Göttinger Miszellen 62, 1983, pp. 19-20.

- ^ Trevor R. Bryce, The Death of Nibhururiya and its Aftermath. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology 76, 1990, pp. 97-105.

- ↑ For an extensive discussion of the vocalization of nfr , nb and other elements of the Egyptian king names see Breyer: Egypt and Anatolien. P. 187ff.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. quoted William L. Moran: Les Lettres d'el Amarna. Correspondence Diplomatique du Pharaon. Paris 1987, p. 383.

- ↑ Rolf Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. Hildesheim 1978, p. 11; 36ff; 72ff; 133 note 3; RS Hess: Amarna Personal Names. Winona Lake 1993, p. 116.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 187 with reference to Kenneth A. Kitchen: Review by R. Krauss, Das Ende der Amarnazeit, Hildesheim 1978. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology 71, 1985, p. 43f .; Hannes Buchberger: Transformation and Transformat. Coffin text studies I. Wiesbaden 1993, p. 249f., Note 326.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 190.

- ^ William L. Moran: The Amarna Letters. Baltimore / London 1992, p. 257. Own translation from English: "Moreover, troops of Ḫatti under Lupakku have captured cities of Amqu, and with the cities they captured Aaddumi. May our lord know this." See also Knudtzon: The El-Amarna-Tafeln. Volume 2, pp. 1272f.

- ↑ Rolf Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. Hildesheim 1978, p. 9f.

- ↑ Krauss, The End of the Amarna Period, p. 19.

- ↑ Kenneth A. Kitchen: Further Notes on New Kingdom Chronology and History. In: Chronique d'Égypte. 43, 1968, p. 328f.

- ↑ Moran: The Amarna Letters. S. XXXV.

- ^ Marc Gabolde: D'Akhenaton à Toutânkhamon. Paris 1998, p. 195.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 198f.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 199.

- ↑ Kenneth A. Kitchen: Further Notes on New Kingdom Chronology and History. In: Chronique d'Égypte. (CdE) No. 43, 1968, p. 319.

- ^ Julia Samson: Royal Inscriptions from Amarna (Petrie Collection University College, London). In: Chronique d'Égypte (CdE) 48, 1973, p. 243ff .; Julia Samson: Royal Names in Amarna History. The Historical Development of Nefertiti's Names and Titles. In: Chronique d'Égypte (CdE) 51, 1976, p. 36ff.

- ↑ Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. P. 18f.

- ↑ Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. P. 15 with reference to E. Meyer: Geschichte des Altertums. 2nd volume, 2nd edition, 1st section, 1928, pp. 399f.

- ^ Krauss: End of the Amarna period. P. 12.

- ^ Gabolde: D'Akhenaton à Toutânkhamon. P. 187ff.

- ↑ Monika Sadowska: Semenkhkare and Zananza. In: Göttinger Miszellen 175, 2000, p. 75.

- ↑ a b Monika Sadowska: Semenkhkare and Zananza. In: Göttinger Miszellen 175, 2000, p. 76.

- ^ Trevor R. Bryce, The Death of Nibhururiya and its Aftermath. In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology No. 76, 1990, p. 97.

- ↑ a b c d e Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 195f.

- ↑ See v. a. Rolf Krauss: The end of the Amarna era.

- ↑ Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. P. 50f.

- ↑ Erik Hornung: Studies on the chronology and history of the New Kingdom. Wiesbaden 1964, p. 92.

- ↑ Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. P. 52f.

- ^ Edward Fay Campbell (Jr.): The Chronology of the Amarna Letters. With Special Reference to the Hypothetical Coregency of Amenophis III and Akhenaten. Baltimore 1964, p. 138.

- ↑ Hornung: Investigations. P. 65.

- ↑ Hornung: Investigations. P. 66.

- ↑ Gabolde: The end of the Amarna period. P. 38.

- ↑ a b Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. P. 12.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Helck: Relations between Egypt and the Middle East in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC Chr. 2nd edition, Wiesbaden 1971, p. 182.

- ↑ Erik Hornung: The tomb of the Haremhab in the Valley of the Kings. 1971, p. 16.

- ^ P. Newberry, in: Howard Carter: Tut-ench-Amun. Volume 2, p. 227.

- ↑ Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. P. 13, note 3.

- ↑ Erik Hornung: Aja as Crown Prince. In: Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (ZÄS) 92, 1966, p. 101.

- ↑ Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. P. 176.

- ↑ Krauss: The end of the Amarna period. P. 13.

- ↑ Christoffer Theis: The letter of Queen Daḫamunzu to the Hittite King Šuppiluliuma I in the light of travel speeds and the passage of time, in: Thomas R. Kämmerer (Ed.): Identities and Societies in the Ancient East-Mediterranean Regions. Comparative approaches. Henning Graf Reventlow Memorial Volume (= AAMO 1, AOAT 390/1). Münster 2011, pp. 306-310.

- ↑ Jared L. Miller: Amarna Age Chronology and the Identity of Nibḫururiya In the Light of a Newly Reconstructed Hittite Text. In: Altorientalische Forschungen 34, 2007/2, pp. 252ff.

- ^ Miller: Amarna Age Chronology. P. 252.

- ^ Ruggerio Stefanini: Haremhab in KUB XIX 15? In: Atti e memorie dell'Accademia Toscana di Scienze e Lettere "La Colombaria" 29 , 1964, pp. 70-71.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 205f .; Miller: Amarna Age Chronology. P. 253f.

- ^ Gernot Wilhelm: Muršilis II. Conflict with Egypt and Haremhab's accession to the throne. In: The World of the Orient. Vol. 39, 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Miller: Amarna Age Chronology. P. 254f.

- ^ Miller: Amarna Age Chronology. P. 255.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 206; Wilhelm: Muršilis II. Conflict with Egypt and Haremhab's accession to the throne. P. 111ff.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 193.

- ^ C. Vanderleyen: L'Égypte et la vallée du Nil. Tome 2: De la fin de l'Ancien Empire à la fin du Nouvel Empire. Paris 1995, p. 458.

- ↑ A. Hagenbuchner: The correspondence of the Hittites (= texts of the Hittites. Vol. 16). Kammerhuber, Heidelberg 1989, No. 344 (KUB III, 60).

- ^ A. Goetze: Plague Prayers of Mursilis. In: JB Pritchard (Ed.): Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. 1950, p. 395 .; R. Lebrun: Hymnes et Prières Hittites. Louvain-la-Neuve 1980, 211-212.

- ↑ Horst Klengel: Hattuschili and Ramses. Hittites and Egyptians - their long way to peace. Mainz 2002, p. 48.

- ↑ Christoffer Theis: The letter of Queen Daḫamunzu to the Hittite King Šuppiluliuma I in the light of travel speeds and the passage of time, in: Thomas R. Kämmerer (Ed.): Identities and Societies in the Ancient East-Mediterranean Regions. Comparative approaches. Henning Graf Reventlow Memorial Volume (= AAMO 1, AOAT 390/1). Münster 2011, p. 324f.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 196.

- ↑ Artur and Annelies Brack: The grave of the Haremhab. Mainz 1980, pl. 49a-b; Wolfgang Helck: Documents of the 18th Dynasty. Translations for issues 17-22. Berlin 1961, 391-392.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 203.

- ^ Breyer: Egypt and Anatolia. P. 201.

- ↑ a b So Volkert Haas: The threatened cosmos. Epidemics in the Hittite Empire. Online article from Freie Universität Berlin from June 4, 2011; See also Horst Klengel: Epidemics in Late Bronze Age Syria-Palestine. In: Y. Avishur, R. Deutsch (Ed.): Epigraphical and Biblical Studies in Honor of Prof. Michael Heltzer. Tel Aviv / Jaffa, 1999, pp. 187–193.

- ↑ Helck: Relationships. P. 183.