KV62

|

KV62 |

|

|---|---|

| place | Valley of the Kings |

| Discovery date | November 4, 1922 |

| excavation | Howard Carter |

| Previous KV61 |

The following KV63 |

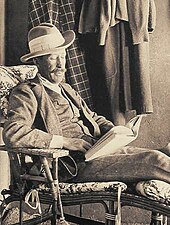

KV62 (KV as an acronym for Kings' Valley) refers to the tomb of Tutankhamun in Egyptology in the Valley of the Kings in West Thebes . In the order in which the tombs in the valley were discovered, it is the 62nd ancient Egyptian tomb and is located in the eastern area of the royal necropolis. KV62 was discovered on November 4, 1922 on behalf of his financier George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon , usually referred to only as Lord Carnarvon, by the British archaeologist Howard Carter .

The discovery turned out to be a royal tomb , because due to the cartouche (name ring) with the throne name Neb-cheperu-Re of Tutankhamun , which was next to prints of the royal necropolis at the walled grave entrance, the burial place could clearly be this king of the late 18th dynasty ( Neues Empire : 1550 to 1070 BC, 18th to 20th Dynasty). KV62 was only partially robbed and already closed twice in ancient times.

The tomb of Tutankhamun, who lived from around 1332 to 1323 BC. Ruled, remains a popular burial site in Egypt thanks to its discovery that was effective in public and in the media, with a partially preserved grave treasure and the intact burial of an ancient Egyptian king . KV62 attracted thousands of visitors during the entire excavation period. The evacuation, registration and conservation of the found objects as well as the cleaning of the grave took around ten years to complete. The excavation period was not only overshadowed by the death of Lord Carnarvons in 1923, but was repeatedly accompanied by disputes with the antiquities administration (also antiquities administration - at the time Service d'Antiquités ). A total of 5398 objects were recovered, some of which are now exhibited in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo or have been stored in the museum's magazines since the grave was discovered. Few pieces can be seen in the Luxor Museum . In the course of the construction of the Grand Egyptian Museum, it is planned to present the entire grave treasure there to the public after appropriate restoration. Tutankhamun's mummy is the only one of an ancient Egyptian king that has remained in the Valley of the Kings since it was buried and also after its discovery. From 1926 it rested in the closed, outer gilded wooden coffin in the sarcophagus in the burial chamber, which had been covered with a glass plate. Today the mummy can be seen, covered up to the head and feet, in the antechamber of the tomb in an air-conditioned glass case.

Howard Carter's notes, drawings and diary entries were handed over to the Griffith Institute in Oxford by his niece, Phyllis Walker, after his death in 1939 and have been kept there since then, like some of the negative films by photographer Harry Burton . The remaining negatives are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, for which Burton worked. For archiving and preparation for the Internet was Egyptologist Jaromir Málek responsible. 95% of the documentation on the excavation is freely accessible to everyone on Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation . Carter's excavation diary is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

discovery

prehistory

The collaboration between Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon , whom Carter had met through Gaston Maspero , began in 1907. Howard Carter was firmly convinced that Tutankhamun's tomb was to be found in the Valley of the Kings. In his opinion, there were several indications for this. Among other things, he was able to identify artifacts with the cartouches of Tutankhamun during his excavation campaign from 1905 to 1906 . As further evidence for a burial of the Pharaoh in the Valley of the Kings, Carter also used a small faience beaker with the name Tutankhamuns found in 1905 by the American lawyer Theodore M. Davis , as well as embalming material from the grave KV54 ("embalming depot"), also discovered by Davis in 1907 . Davis himself held this deposit for the tomb of Tutankhamun and had this conclusion published as a result in The Tomb of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou in 1912 . In addition , gold foils could be assigned to the king and his court official Eje from grave KV58 ("chariot grave "), also discovered under Davis in 1909 . The name of Ankhesenamun , Tutankhamun's great royal wife , can also be read on one of these gold foils.

Theodore M. Davis finally declared the Valley of the Kings after many successful years and a less productive excavation in his publication The Tomb of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou as archaeologically exhausted: I fear that the Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted. During the excavation season from 1913 to 1914, he returned his license for the area after working in the Valley of the Kings for more than twelve years. Thereafter, Lord Carnarvon had received permission from the Service des Antiquités de l'Egypte , now the Supreme Council of Antiquities , to carry out excavations in the Valley of the Kings. The excavation license was signed on April 18, 1915 by Georges Daressy and Howard Carter. Work in the Valley of the Kings could not start until 1917 because of the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. By then, Carter had followed all known leads to Tutankhamun and began his systematic search for the grave from 1917. The results of the excavations from 1917 to 1921 were, however, sparse. Between the graves of Ramses II ( KV7 ) and Ramses VI. ( KV9 ) Howard Carter cleared a workers' settlement for Carnarvon and then focused on the surrounding areas when Lord Carnarvon decided in 1921 to terminate the financing agreement. Carter offered to self-finance the dig and ascribe a possible discovery to Lord Carnarvon . This consented at the end of a last excavation season from the following year.

The year in which Carter continued his work for Lord Carnarvon for a final dig in the Valley of the Kings was also a turning point in the history and politics of Egypt . The country gained independence from Great Britain as a kingdom in 1922 and was no longer under British rule . From its founding in 1859 to 1952, the Egyptian antiquities administration was under French and from 1953 ( Republic of Egypt ) exclusively under Egyptian leadership.

Grave of the bird

The local workers gave grave KV62 the name " Tomb of the Bird" or "Tomb of the golden bird". This name goes back to the canary that Howard Carter brought to his house from Cairo to el-Qurna (Gurna) during this excavation season. Carter was so taken with the bird's song in a cafe in Cairo that he bought it from its owner. When asked why he had bought a bird of all things, he answered: “As a friend in the loneliness of the desert.” Carter writes that when he reached Thebes , the bird sang most beautifully and at that moment he thought: “The grave of a bird! ”His employees were also fascinated by the animal and its song, and the workers called it a good luck charm after discovering the first stages of KV62.

After the arrival of Lord Carnarvon and evacuation of all levels, the "lucky bird" is said to have been eaten by a cobra . That was a bad omen for the workers involved in the grave , as this snake ( Wadjet ) was the country goddess for Lower Egypt , alongside the vulture ( Nechbet ), the country goddess for Upper Egypt , a protective symbol of an ancient Egyptian king. Later the death of the canary became part of the Pharaoh's curse . It was important for Howard Carter to reassure his employees and workers and to reassure them that this event was not due to a curse . He told them the bird would be back. After a telegram, Lady Evelyn, Lord Carnarvon's daughter, finally brought another canary with her to Thebes on November 24, 1922.

The discovery

Howard Carter wrote about the search for Tutankhamun's tomb: “At the risk of being accused of post factum prediction, I would like to say that we definitely had the hope of finding the tomb of a particular king, namely that of Tut-ankh-Amen. "

Carter arrived in Luxor on October 28, 1922 , with the excavation season scheduled to begin on November 1. On November 4, 1922, a worker came across a step in the excavation area. After the top step was discovered, rubble was removed from the site. Carter found several intact seals at the top of a bricked-up wall. These "stamp impressions", usually referred to as seal impressions , have the shape of a cartridge . It depicts the god Anubis as a jackal lying over nine prisoners, the so-called nine arches (enemies of Egypt). This seal of the necropolis was a sign of the intactness of a grave, which the responsible overseers of the “city of the dead” had attached after the burial. It was also used after a grave was looted or restored when the grave was closed again. Carter then sent a telegram to Lord Carnarvon:

At last have made wonderful discovery in Valley a magnificent tomb with seals intact recovered same for your arrival congratulations.

“I finally made a wonderful discovery in the valley. Magnificent grave with intact seals. Covered up again until you arrive. Congratulations. "

Until the arrival of Lord Carnarvon, the exposed access was backfilled with rubble. The Lord and his daughter, Lady Evelyn Herbert, arrived in Luxor on November 23rd and 24th .

Legend of the boy who found the grave

The "worker" who found the grave was a child who brought water to the excavation site for the workers and the excavation team. So that a clay water jug had a firm footing in the ground, a hollow had to be made to put it in. The "water boy" came across stone and discovered the first step. In 1925, Harry Burton photographed the young Hussein Abd el-Rassul with a wide necklace with scarabs and sun discs (JE 61896) that had been found in the treasury. According to Zahi Hawass, this was a privilege that could only be bestowed on Howard Carter, who did so to pay tribute to the boy for the discovery.

Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun was not an unknown king due to various finds prior to the discovery of KV62. The archaeological evidence so far, however, did not allow any conclusions to be drawn about his life and work as a ruler. A king named Amentuanch was first mentioned in 1845 by Christian Karl Josias von Bunsen in Egypt's place in world history . Henri Gauthier placed Tutankhamun in the line of kings after Semenchkare and before Eje at the end of the 18th dynasty in 1912 . He ruled from about 1332 to 1323 BC. BC and was born in Achet-Aton ("Horizon of Aton"), the capital newly founded by Akhenaten. Because of his childhood age when he ascended the throne (8-10 years old) and the young age at death (17-19 years), he is usually referred to as the "child king" ( Boy King ).

Tutankhamun's predecessor

Tutankhamun's predecessors after Akhenaten were rulers with the proper names Se-mench-ka-Re-djeser-cheperu ("Consolidated with Ka-forces of Re (and) holy apparitions") and Nefer-neferu-Aton ("The beauties of Aton are beautiful "/" The perfection of the aten is perfect "). Both kings had the same throne name Anch-cheperu-Re ("Living are the appearances of Re"), which either stand alone next to the proper name or are accompanied by epithets (adjectives) that clearly belong to Akhenaten:

- Anch-cheperu-Re meri-wa-en-Re : Anch-cheperu-Re, loved by the only one of the Re ( wa-en-Re is part of the name of the throne name of Akhenaten)

- Anch-cheperu-Re meri-nefer-cheperu-Re : Anch-cheperu-Re, loved by Nefer-cheperu-Re ( Nefer-cheperu-Re is Akhenaten's throne name)

In the case of identical throne names of kings, the determination of an ancient Egyptian king is difficult if the proper name is missing and there are no other indications for a clear identification. The same throne name also exists for a female ruler ( Anchet-cheperu-Re ), characterized by the female T-ending, with epithets identical to Akhenaten. Rolf Krauss sees Akhenaten and Nefertiti's first-born daughter Meritaton in this person . The order of the kings before Tutankhamun is indicated differently in the chronologies . The Krauss dating takes into account Meritaton before Semenchkare without Neferneferuaton, others do not name Meritaton in the position of a king and either list Semenchkare before Neferneferuaton or both together, or Semenchkare after Neferneferuaton.

If Semenchkare is spoken of in relation to Tutankhamun's grave treasure, the throne name Ankh-cheperu-Re is usually meant. Like the proper name Neferneferuaton, this can be found on objects from KV62. According to Christian E. Loeben , Semenchkare's personal name is difficult to read on a vase made of calcite (Egyptian Museum Cairo, JE62172, Carter no. 405). According to him, the names (throne and proper names) of Semenchkare and Akhenaten can be read here, while previous name reconstructions, including those of Howard Carter, of a common mention of Akhenaten and his father Amenophis III. went out and raised the question of a co-regency of father and son.

The name of Tutankhamun

The original proper name of Tutankhamun, "Living Image of Amun" ( Tut-anch-Amun - Twt-ˁnḫ-Jmn ), was Tutanchaton, "Living Image of Aton" ( Tut-anch-Aton - Twt-ˁnḫ-Jtn ). At what time the name change took place is unknown, but probably before the change of residence from Achet-Aton to Memphis . As with Akhenaten, only the proper name was changed, the throne name ( Neb-cheperu-Re - Nb-ḫprw-Rˁ ) remained.

An ancient Egyptian king had a so-called " royal statute ". This consisted of five names, which together represented a kind of "government program" of the ruler. He received the proper name at birth, the Horus , Nebti , Gold , and throne names at the accession to the throne . The name (ancient Egyptian ren ) of a person or of things was of particular importance in ancient Egypt because it was what made existence possible. Only what could be mentioned by a name actually existed and would last. The name was an essential part of a person's being and as important as Ka , Ba and Ach . “To give someone a name means to put their energy into words.” The name was therefore also significant for the afterlife in the hereafter . The goal of name cancellations, such as What happened, for example, with Hatshepsut or Akhenaten , was to wipe out the memory of the people and thus prevent their immortality and eternal continuity. Such a process is called Damnatio memoriae ("damnation of memory"). Also the erasure of the name of the god Amun , partially executed by Akhenaten , even in the name of his father Amenophis III., Or in his later reign also the erasure of the plural spelling “gods” ( njerr.w - netjeru ), which according to his definition of only God (namely Aton ) contradicted, pursued this intention.

Hieroglyphs go to the proper name of a king

|

Name of the king with the addition:

|

- ( S3 Rˁ Twt ˁnḫ Jmn ḥq3 Jwnw šmˁj - Sa Ra Tutankhamun heqa Iunu schemai ), "Son of Re, living image of Amun, ruler of the southern Junu ( Heliopolis )"

King's throne name:

|

- ( Njswt-bjtj Nb-ḫprw-Rˁ - Nisut-biti, Neb-cheperu-Re ) "King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of Figures, a Re"

On the walls in the burial chamber, the proper name Tutankhamun is only on the north wall, otherwise his throne name Neb-cheperu-Re and, also on the north wall above his ka, the hieroglyphs that introduce the Horus name "Strong bull, with perfect births", this himself but do not mention there. The representation of the king is defined at this point as his ka. The cartouches found on the walled-up passages as a sign of sealing, like the intact clay seals of shrines or boxes, only bore the throne name Neb-cheperu-Re ("Lord of figures, a Re") of the deceased ruler and not the proper name Tutankhamun. The latter can be read together with the throne name on various objects from the tomb.

excavation

On November 24th the stairs were completely cleared. 16 steps ended in front of a walled blockage, in the upper area of which Carter had already seen the seal of the necropolis ("city of the dead"). After the entire wall could be viewed, the throne name of Tutankhamun, written in a cartouche, was found in the lower part of this wall : Neb-cheperu-Re and not his personal name Tutankhamun. The identification of an ancient Egyptian ruler is easier and clearer via the throne name, as there was often duplication of names for ancient Egyptian kings, such as Thutmosis , Amenophis or Ramses . However, this was not a guarantee that it was the tomb of the "child king", because on the walled entrance to tomb KV55 there was also the throne name of Tutankhamun, during whose reign this burial is classified. Two days later, the wall to the corridor was removed and the corridor behind it was also cleared of rubble. In the late afternoon of November 26th, Carter and his excavation team reached a second door block, which was also walled up and sealed several times, in which he punched a hole and held a candle to check for any leaking fouling gases. Howard Carter described this moment as one of the most beautiful he was able to experience. His frequently quoted words were:

At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold - everywhere the glint of gold.

“At first I saw nothing, the warm air escaping from the chamber made the candle flame flicker, but then, as my eyes got used to the light, I saw details of the room appear out of the dust, strange animals, statues and gold, shining everywhere the shine of gold. "

- Situation at the beginning of the excavation

Excavation license and division of finds

The excavation license (also excavation concession) comprised a total of thirteen points that were decisive for the work of Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings. The concession for excavations in the Valley of the Kings at that time corresponded to the one that had been valid for the excavations of the German Orient Society in Tell el-Amarna under the direction of Ludwig Borchardt . Among other things, the license holder had to pay for all costs and was responsible for any risk of the excavation. Howard Carter, who acted as an archaeologist for Carnarvons, had to be present during the entire excavation period. The excavation work was under the control and supervision of the antiquities administration (Service d'Antiquités) . This not only had the right to supervise the work, but also to change the method of excavation if it seemed more promising than that of the excavator. The license also stipulated that in the event of a discovery the Inspector of Upper Egypt in Luxor - a position that Howard Carter himself held from 1899 to 1904 - was to be notified. At the time of the excavation of KV62, this was Reginald Engelbach . The excavator was given the privilege of being the first to enter an open grave or monument.

Points 8 to 10 determined the distribution of the finds. For example, it was stipulated that the mummies of kings, princes or high priests, along with their coffins and sarcophagi, are the property of the Antiquities Administration. Items from intact, pristine graves should go to the museum without sharing with the excavator. If it was a grave that had already been searched for, the Antiquities Administration claimed, apart from mummies, objects of particular value and of historical and archaeological importance. The rest should be shared with the excavator. He should also be compensated for his expenses and efforts in such a case.

The point of contention after the discovery was whether grave KV62 was an intact or already robbed grave. Carter stated that the grave had been robbed at least twice in antiquity and that it should not be considered intact because there was evidence that objects from the grave equipment were missing. The antiquities administration did not share this view. For them the grave with the seals of the necropolis and the king was an intact grave, the entire contents of which was the property of the antiquities administration, which is why there would be no division of the finds.

After Lord Carnarvon's death on April 5, 1923, the excavation license passed to his widow Lady Carnarvon, who continued to support Howard Carter. He applied for an extension of the license on her behalf, which was granted. In 1929 Lady Almina gave up the excavation license. It was not until 1930 that the Lord Carnarvons family received a sum of £ 35,971 in compensation , which roughly corresponded to the total funds expended for the entire excavation period. Howard Carter had been promised about a quarter of the amount by Lady Carnarvon, and he eventually received the amount of £ 8,012. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which had been involved throughout the excavation period, received no compensation from Egypt for the resulting work Out-of-pocket expenses that came to about £ 8,000 for the museum.

Pierre Lacau, director general of the antiquities administration since 1914 and successor to Gaston Maspero , imposed stricter requirements for excavators in Egypt in 1923. The previous practice of dividing finds was also affected by this. The original division “in equal parts” (à moitié exacte) for the excavator and Egypt was no longer applicable . Although there had been a vague promise to possibly share duplicate items between the excavator and Egypt, in the end all finds, regardless of the find situation, were from then on property of the country of Egypt and the export of antiquities was completely prohibited. For Joyce Tyldesley , this explains, for example, that Flinders Petrie gave up his work in Egypt and began excavations in Palestine. He was dependent on private donors and could no longer export objects for museums from Egypt.

In 1983, the regulation for the division of finds during excavations was relaxed and provided 10% of the objects as a share for the excavator. In 2010, Zahi Hawass obtained an amendment to the law so that no excavator should receive a single find, unless it was already present in multiple forms in the collection of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and thus only a "duplicate" of some of the exhibits.

Grave designation and subsequent graves

The numbering system of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings goes back to John Gardner Wilkinson , who first traveled to Egypt in 1821 and, while recording inscriptions, also numbered the royal tombs known up to that point in time. Previously there was already numbering by, for example, Richard Pococke , Jean-François Champollion , Carl Richard Lepsius or Giovanni Battista Belzoni . Wilkinson's system has been maintained to this day. All grave numbers in the Valley of the Kings are preceded by the abbreviation KV (for King's Valley ), followed by the number of the grave, with the graves in the western valley being referred to as both KV and WV (for West Valley ). Similarly, the private graves of civil servants or nobles in Thebes are predominantly marked with TT ( Theban Tomb - "Theban grave") or in Amarna with AT ( Amarna Tomb - "Amarna grave") and also a consecutive number. In 1922, grave KV62 was the 62nd grave to be discovered in the Valley of the Kings. Howard Carter himself gave it the number 433, in the order of his discoveries since 1915. KV62 is not an alternative name, but in addition to the commonly used term "Tutankhamun's tomb", the one used internationally in Egyptology for this royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

Since Tutankhamun's grave was discovered in 1922, only two other graves have been found in the Valley of the Kings: KV63 (2005) under the direction of Otto Schaden, formerly from the University of Memphis , and KV64 (2011) as part of the University of Basel Kings' started in 2009 Valley Project by Egyptologists from the University of Basel under the direction of Susanne Bickel. KV63 could not be assigned to any person, but was due to the finds in the period of the governments of Amenhotep III. assigned to Tutankhamun. KV64 is therefore considered to be originally laid out in the 18th dynasty, in which there was a second burial of Nehemes-Bastet, daughter of a priest and "singer of Amun ", in the 22nd dynasty ( Third Intermediate Period ) .

Organization and excavation team

Overall, the find posed a major organizational and logistical challenge for Howard Carter. There had previously been no comparable find in Egypt and it was up to Howard Carter to develop a system to document and recover the grave treasure. George Andrew Reisner made a similar discovery in 1925 . Three years after the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb, he found the only partially robbed tomb of Hetepheres I in Gizeh , the mother of King Cheops (4th Dynasty, Old Kingdom ). In addition to an empty sarcophagus, it contained various pieces of furniture made of wood, a canopic chest, jewelry and other objects. A find comparable to that of KV62 was the discovery of the grave of Psusennes I by Pierre Montet , who had also found this grave untouched.

Howard Carter described the finds in KV62 as "a matter that could not be handled by a man." The number of objects found exceeded any previous "ordinary" find in Egypt. Not only did workers have to be hired, but plans for general work, the power supply, cataloging and recovery of objects found in the grave, their preservation and their transport to Cairo had to be drawn up. Other points were the need for and the procurement of various packaging materials for safe transport as well as suitable and trained personnel for handling and processing the objects on site. After the first inspection of the grave, it was foreseeable that the work would take more than a season. In fact, due to various circumstances, working hours during a season were limited to a few months or weeks within a year. At the time of the tomb's discovery, there were academic staff at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in Thebes and Albert M. Lythgoe , head of the museum's Egyptian department, offered his assistance. The excavation team was put together from December 7th to 18th, 1922 with his help, which, in addition to Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon, finally included:

- Arthur C. Mace , former assistant curator and curator of the Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Alfred Lucas, chemist in the Department of Antiquities ( Département d'Antiquités or Service d'Antiquités )

- Harry Burton , photographer for the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Arthur R. Callender , architect and engineer, longtime friend of Howard Carter

- Percy E. Newberry , professor of Egyptology at the University of Liverpool and Carter's first mentor

- Alan Henderson Gardiner , Egyptologist and philologist

- James Henry Breasted , Founder and Director of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago

- Walter Hauser, former member of the Egyptian Expedition of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Lindsley Foote Hall, former member of the Egyptian Expedition of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Richard Adamson, former sergeant, guard and security

During the second excavation season (1923-1924) Richard Bethell, a member of the Egypt Exploration Society , was Howard Carter's assistant. From 1922 to 1932, other employees included Douglas E. Derry and Saleh Bey Hamdi in the investigation of the royal mummy, Battiscombe George Gunn for the evaluation of ostraka , the botanist LA Boodle, HJ Plenderleith from the British Museum for analytical support, James R. Ogden for evaluating the gold work in the tomb; and GF Hulme of Geological Survey of Egypt .

The excavation team was supported by numerous local workers, who were headed by the so-called "rice" (foremen), to remove the rubble and rubble and to transport materials and objects from the grave. Often children were given the task of bringing water to the excavation site.

On-site premises were also required to conserve and store the finds after they were recovered from the grave before they could be transported from the west bank of the Nile near Luxor to Cairo . The use of already open graves in the Valley of the Kings offered itself for this purpose, but had to be approved by the ancient administration. This is how the grave of Ramses XI served. ( KV4 ) as a general storage room for "lower value finds", the grave of Seti II ( KV15 ) was used as a conservation laboratory and a photo studio, while Harry Burton's grave KV55, not far from KV62, was used as a darkroom.

Working methods and documentation

In contrast to the approach taken by, for example, Theodore M. Davis during the excavation of grave KV55, Howard Carter and his team worked very carefully. This contributed to the fact that not only the grave treasure was largely preserved, but also that, thanks to the documentation, it can still be explored many decades after the grave was discovered. Flinders Petrie (William Matthew Flinders Petrie), under whom Howard Carter had worked in Amarna in 1892 , remarked while working together about the then 18-year-old:

Mr. Carter is a good-natured lad whose interest is entirely in painting and natural history ... it is of no use to me to work him up as an excavator.

"Mr. Carter is a good-natured boy whose interest is entirely in painting and natural history ... it is of no use to me to train him to be an excavator. "

Thirty years later, on the discovery of the Royal Tomb, Petrie said, "We are lucky that all of this is in the hands of Carter and Lucas." According to TGH James , this was the greatest praise Carter could ever have received.

Howard Carter's system provided for all finds to be photographed, numbered and cataloged on the spot, and in some cases to be protected from complete disintegration by conservation measures in the grave so that they could be transported and restored later. Carter also made detailed drawings or sketches for many pieces.

Numbering system

The objects found in the grave were numbered according to object groups in the chambers. The walled up and sealed doorways (including partition walls), the stairs and the corridor were also counted as “rooms”. There were a total of 620 object groups, the sub-categories of which within the group were identified alphabetically by letters. For example, the jewelry and other accessories belonging to the mummy (256) were assigned to group number 256, from the golden death mask with number 256a to number 256-4v (256vvvv), an iron amulet in the form of a headrest. Objects related to the Anubis Shrine were given the main number 261 (261–261r). The object group 620 from the side chamber ( annexes ), which is numbered from 620: 1 to 620: 123, is an exception to this . The complete grave inventory was recorded according to this system.

| chamber | Object group number |

|---|---|

| Entrance stairs | 1–3 (3 object groups) |

| first sealed door | 4th |

| corridor | 5–12 (8 object groups) |

| second sealed door | 13 |

| Antechamber | 14–27 and 29–170 (156 object groups) |

| fourth sealed door to the burial chamber | 28 |

| Burial chamber | 172–260 (89 object groups) |

| Treasury | 261–336 (76 object groups) |

| third sealed door to the annex | 171 |

| Side chamber | 337–620 (284 object groups) |

documentation

The location sketching of individual objects in the find situation in the antechamber was not only done photographically by Harry Burton, but also graphically by the architects from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Walter Hauser and Lindsley Foote Hall. Both left the excavation team after completing their final work in the antechamber because they could not cope with "the quick-tempered temperament" of Howard Carter. Howard Carter completely traced the contents of the burial chamber. No drawings were made for the side chamber and the treasury. The photographs were the responsibility of Harry Burton, the drawings and cataloging were done by Howard Carter and Arthur Callender, while the chemist Alfred Lucas of the Department of Antiquities and Arthur C. Mace, curator of the Department of Egyptian Antiques at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, were responsible for the chemical analysis, conservation and restoration were responsible. The philologist and Egyptologist Sir Alan Gardiner , known for his work with Adolf Erman on the creation of a dictionary of the Egyptian language and, among other things, the Gardiner symbol list that appeared in his Egyptian grammar , was responsible for the translation and analysis of the inscriptions on the objects in the grave deals. Percy E. Newberry analyzed the herbal additions found in the grave.

Due to this careful procedure, the objects from the antechamber were only removed from the grave after about seven weeks, for example. Howard Carter described the antechamber situation:

It was slow work, painfully slow, and nerve-racking at that, for one felt all the time a heavy weight of responisibility. Every excavator must, if have any archaelogical concience at all. The things he finds are not his own property […] They are a direct legacy from the past to the present age […]

“It was slow work, painfully slow and also nerve-wracking because you feel the heavy weight of responsibility all the time. Any excavator should if he has any archaeological awareness. The things he finds are not his property [...] They are a direct legacy from the past to the present day [...] "

- Working in the grave

During the inventory, the objects were given signs with the corresponding numbers and photographed again by Harry Burton so that the original position in the grave could later be traced. For Howard Carter this "constant care" was necessary so that even the smallest finds were not separated from their "identification slips". At the end of an excavation season, the complete find history for each object was given. This approach included:

- the dimensions, scale drawings and archaeological records,

- Records of the inscriptions by Alan Gardiner,

- Lucas records of the conservation process used,

- a photograph showing the exact location of the object in the grave,

- a scale photograph or a series of images depicting the object alone,

- they were boxes, a series of views showing the clearing out in its various stages.

The documentation of the excavation of KV62 finally comprised a total of 3200 object cards ( index cards ) described by Carter, some with drawings. Some cards also have notes from Alan Gardiner and Alfred Lucas. In addition, around 1850 photographs by Harry Burton as well as Howard Carter's excavation diary and his personal notes. In addition, the three-volume publication The tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen (1923–1933) was published as a preliminary report. Further brief reports can be found in Arthur C. Mace's digging diaries for the first and second seasons.

Recovery and transport

Apart from the salvage and preservation, the preparation for the transport of the artifacts had to be organized. Each find was individually packaged. For the objects from the antechamber alone, in addition to the furniture, 89 boxes and 1,500 m of cotton fabric for upholstery and packaging in 34 wooden boxes were required. Other materials used for packaging were cotton wool and towels. A steamship was available to Cairo through the antiquities administration, but it was still about 10 km from the laboratory in the Valley of the Kings, where the packed objects were, to the bank of the Nile. This path is relatively straight, but there were windings and inclines that made transport difficult. At the time, the road to the Valley of the Kings was unpaved and automobiles were a rarity. For transportation from the valley to the Nile , there were several options: donkeys, camels, porters or Decauville - Feldbahn with Güterloren . The decision was made to use this so-called “portable railway”. While the individually loaded wagons were pushed forward, the tracks of the route covered were dismantled and relocated in front of the railway. The heat in the valley was a great burden for the workers and excavators and the tracks, which were extremely heated by the sun, were more difficult to lay during the transport. Reaching the banks of the Nile took 15 hours. The shipment to Cairo took about a week. The most valuable objects were unpacked there and then exhibited in the Cairo museum, which opened in 1902. A few finds, such as Tutankhamun's golden mask or the golden coffin, were transported to Cairo by train, for which a special car with armed guards was made available.

Excavation periods and events

The excavation period comprised a total of nine excavation seasons of different lengths:

- Season: October 28, 1922 to May 30, 1923

- Season: October 3, 1923 to February 9, 1924

- Season: January 19 to March 31, 1925

- Season: September 28, 1925 to May 21, 1926

- Season: September 22, 1926 to May 3, 1927

- Season: October 8, 1927 to April 26, 1928

- Season: September 20 to December 4, 1928

- Season: 1929 to 1930: no work on the grave

- Season: September 24th to November 17th, 1930

From November 24, 1922, Tutankhamun's tomb was excavated by Carter and his scientific team. The excavation continued with all final conservation work until 1932. However, the period of a season did not mean that during that time work was carried out exclusively on the items in the tomb. For example, KV62 was filled in again at the end of the season for safety reasons in the first few years and had to be cleared of rubble again in the next excavation season in order to be able to continue the work. In addition, Howard Carter traveled from Luxor back to Cairo in order to clarify various points with the Antiquities Administration or the Ministry of Public Affairs or to extend the concession. With each season new materials for packaging and transport, chemicals for preservation had to be organized and workers had to be hired. For example, Tuesday was a day off for workers as it was market day. Waiting for local craftsmen, such as stonemasons or carpenters, also had an effect on the continuation of the work. Howard Carter complained about such delays several times in his digging diary. The effective working hours decreased due to these various circumstances. Another factor that had a negative effect on the continued work was the frequent presence of visitors and press representatives in the grave.

For Howard Carter, giving up Lady Carnarvon's excavation license meant that he no longer had official access to the grave and that his scientific work could not continue as before. From then on, he was under the supervision of inspectors from the Antiquities Department, who had the keys to the grave and laboratory. They also decided who was allowed to visit the grave. Although these circumstances were very unsatisfactory for Carter, he worked on the grave and the remaining objects to be recovered as well as in the laboratory until February 1932. Funding for the work on the excavation lay from 1930 onwards with Howard Carter himself and Egypt.

Strike and closure of the tomb

As early as December 1923, only the Antiquities Administration determined who could visit the grave and be a member of Howard Carter's excavation team. During the second excavation season in February 1924, there was a scandal that Carter does not include in his records. His notes end before the events and after the sarcophagus lid has been lifted on February 12 in the presence of an invited audience. The incident is also not mentioned in the continuation of his recordings for the next season.

The grave was scheduled to open on February 13th for the press to visit the burial chamber and sarcophagus. After that, Carter wanted the archaeologists' wives to be able to see the open sarcophagus. The Egyptian government, however, forbade the ladies from visiting the burial chamber. The letter sent to Howard Carter stated: “I am sorry to inform you that I have received a telegram from the Secretary of State for Public Works. His speeches made within the ministry unfortunately do not allow the wives of your employees to visit the grave tomorrow, February 13th. ”Even Lady Almina Carnarvon, who has held the excavation license since the death of her husband and continues to finance the excavation, was the visit thus denied. Howard Carter saw this as a personal affront to himself and the license holder and saw only one possibility: the workers immediately stopped working and he closed the grave. The situation worsened and Carter was told that "it was not his grave". He received another letter prohibiting him and any member of the excavation team from entering the tomb. As a result, Lady Carnarvon was revoked on February 20, 1924, her excavation license. Work in KV62 was only resumed in January 1925 after tedious discussions about how to proceed. The new concession for Lady Carnarvon was issued on January 13, 1925. During this period the heavy sarcophagus lid, which was broken in antiquity but was cemented, hung on cables over the sarcophagus tub and the coffins inside, a circumstance that later archaeologists described as irresponsible. Howard Carter eventually returned, also to Pierre Lacau's relief, to work on the grave. Herbert E. Winlock commented that "there was no better person to whom these precious finds could be entrusted." According to Nicholas Reeves, this was "a job nobody really wanted".

Press and reporting

The news about the discovery of a locked royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings spread quickly in Egypt. Rumors of immeasurable treasures arose just as quickly, although the complete contents of the grave were still unknown. Numerous letters of congratulations and offers of help for Howard Carter were received. The press literally assaulted Lord Carnarvon and his excavation team. The sudden and great interest of the world public in an archaeological find was unusual and strange for Carter, since this had never happened until the discovery of grave KV62. He considered the unexpected attention from the press and visitors in the valley as "embarrassing." The first press report on Tutankhamun's tomb appeared on November 30, 1922 after the official opening of the tomb, the antechamber and the extension, in the London Times . The discovery of grave KV62 was the first to result in such constant reporting.

After much deliberation and discussions with Howard Carter and Alan Gardiner, Lord Carnarvon signed an exclusive contract for an initial coverage with The Times on January 9, 1923 , because it was "the best newspaper in the world". This should relieve the excavation team, because with this contract, the information on the progress of the work on the grave only had to be passed on to a newspaper instead of repeatedly to countless individual press employees. That is why all the other newspapers, including the Egyptian, could only report after publication in the Times. The conclusion of this contract should bring Carnarvon £ 5,000, plus 75% of the revenue from the Times from selling the news to other newspapers. As early as June of the same year, income from reporting was £ 11,600 . Arthur Merton, a Times official, was named by Carter as a member of the excavation team.

These decisions caused resentment and indignation in the press agencies. Large newspapers worldwide reported on the contract and wrote, among other things: "[... to degrade the world of science to a whore for sale ...]" or "[... to sell out archeology and world history.]" Albert M. Lythgoe , at the time Head of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Egypt expedition, advised the museum's director, Edward Robinson, of the special circumstances and that the museum should be careful about information about the tomb. Robinson noted that although the "lion's share" of the work in KV62 would be done by employees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the grave was in the hands of Carnarvon and Carter and therefore the right to public announcements was with them.

The newspapers called these circumstances "scandalous" and protested the contract with the Times. As the excavation progressed, they increasingly complained to Pierre Lacau, the director of the antiquities administration. The Egyptian newspapers complained that they were denied access to an ancient Egyptian royal tomb. Lacau appealed to Howard Carter to reserve at least one day in the grave for personal and press visits. The latter refused, "because his scientific assignment would take a lot of effort" and he emphasized that the antiquities administration, due to the concession, "has no right to demand such an event that would mean an unreasonable interruption of the archaeological work". Visitors, whether from the press or on recommendation, caused additional work both before and after a visit: the access routes had to be secured, power cables had to be laid differently, tools and work materials removed and, above all, the objects still in the grave must be protected. For the excavation team, the days on which work could not continue quickly were "lost days". Howard Carter repeatedly noted in his digging diary no work was done in the tomb or work progressing slowly .

Lord Carnarvon , whose health had been impaired for a long time, died in Cairo on April 5, 1923, a few months after the grave was discovered and a short time after the burial chamber was opened. His death was followed by the story of the " Curse of the Pharaoh, " which was circulated by the press around the world, but vehemently denied by Howard Carter. Carnarvon's death also presented Carter with the difficulty of dealing with the grave's visitors and press staff himself as an excavator. The contract with the Times became increasingly burdensome. For Morcos Bey Hanna, the new minister for public affairs since January 1924 and not fond of the British in Egypt, called the contract, which directly excluded the Egyptian press, a mistake. Carter assured that the contract would expire after April 1924 and that there would be no new signing. From December 1923, the visits by the press and reports to the press staff took place mostly on Mondays, before the day off for the workers. Finally, to provide the press with information, there were press views , comparable to on-site press conferences. Howard Carter noted that despite the fall of the Times monopoly, the Egyptian press showed little interest in the tomb.

According to the first report in the Times, the first major contribution to Tutankhamun's grave was to be read a week later in a supplement to the Vossische Zeitung on December 7, 1922. It appeared after a lecture by Ludwig Borchardt, under whose direction the bust of Nefertiti had been discovered during the excavations of the German Orient Society in Tell el-Amarna . The Times published the first photos of Harry Burton on January 30, 1923. The first color photograph of a grave object was that of the golden throne found in the antechamber on November 10, 1923. The steady, international coverage of the excavation work in KV62 lasted almost the entire processing period of the objects from the grave.

Visitors

After the discovery and throughout the excavation period, the tomb not only attracted the international press but also aroused the curiosity of numerous tourists and locals. Howard Carter described dealing with visitors as "a special matter of sensitivity". A real tourism developed to visit the Valley of the Kings and grave KV62. Particularly high-ranking and registered visitors were given permission to visit the grave and the laboratory (KV15), initially from Carnarvon or Carter themselves, later from the antiquities administration. Many visitors came because of letters of recommendation, some of which Carter considered to be bogus. He was not fond of interruptions from the press or from visitors who were interested in the grave and were very angry about these "disturbances". In his excavation diary he emphasizes that he is “not a tourist guide, but an archaeologist”. Visitors of all kinds not only mean delays in the conservation and recovery of the grave treasure. As long as the partly fragile objects were in the grave, they could be damaged by visitors directly through contact or indirectly through sand that was brought with them and blown up. The sand carried into the grave by tourists is still a threat to the wall paintings in the grave chamber.

Howard Carter mentions the high number of visitors during the excavation in a letter to his uncle Henry William Carter in February 1926. "Since January 2nd alone, over 9,000 people had come to see Tutankhamun's tomb". Nicholas Reeves puts the number of visitors from January 1 to March 15, 1926 at the height of the hysteria about the grave at 12,000. Not all tourists in the valley had visited the grave themselves, but the area around the archaeological site "besieged". Despite his aversion to the curious, Carter occasionally allowed those present to see the artifacts he found, which he then had uncovered from the grave. This included, for example, the transport of the ritual beds or Tutankhamun's “mannequin”.

Despite Carter's objections to visitors of any kind, the period in the first excavation season, February 18-25, 1923, was reserved for press representatives and visitors to the grave. Howard Carter noted that while the antechamber was cleared, about a quarter of the time during the excavation season was spent on visitors only. For February 10, 1925, he noted 40 visitors to the tomb in his excavation diary, who had been selected and invited by the Egyptian government. To his regret, few of the guests showed any real interest. There was also little interest from the press and there were no questions. Carter was also amazed at the absence of the Egyptian press, which had complained a year earlier about not having access to this ancient Egyptian royal tomb.

In his excavation diary, Carter sometimes lists the names of the visitors to KV62, who not only included the employees of the antiquities administration, the inspector for Upper Egypt or the wives of the employees of the excavation team. These included personalities of the nobility and members of royalty. In March 1923 the Queen of the Belgians, Elisabeth Gabriele in Bavaria , who was also present at the official opening of the grave on February 18, 1923, visited the laboratory. King Fu'ad I , first king of the Kingdom of Egypt (1922–1953), proclaimed in 1922 , visited the grave and laboratory in 1926. The King of Afghanistan followed in 1927, the Crown Prince of Italy in 1928 and in 1930 the Crown Prince of Sweden, Gustav Adolf Hereditary Prince of Sweden .

The tomb in ancient times

Maya was probably responsible for the tomb of Tutankhamun , a high official with the title of treasurer under Tutankhamun, who later served under King Haremhab . It is not known who chose Tutankhamun's grave. Generally, Eje, Tutankhamun's successor, is assumed to be the client. From Maya there are burial objects for the king, which identify him as a devoted servant. The name of his assistant, Djehutimose, is written on a calcite vase found in the side chamber. Both persons are connected to the restoration work of grave KV43 ( Thutmose IV. ), Which dates to the 8th year of Haremhab's reign, which was discovered in 1903 by Howard Carter for Theodore M. Davis. Nachtmin , another high dignitary under Tutankhamun, is also an option .

Carter found evidence that the ancient chambers of KV62 had been robbed at least twice immediately after the royal burial. Not only did two different seals on the exposed first wall lining at the grave entrance testify to this, but also the deranged objects in the antechamber (I) and in particular in the extension ( Annex Ia ) spoke in favor of it. Another clue was that when comparing different inventory lists of chests or boxes, it was found that a number of artifacts were missing, which could prove the theft of some objects. About 60% of the jewelry had been stolen from the chests and boxes in the treasury, as well as vessels made of precious metals. In a chest in the antechamber was found a linen cloth knotted together containing rings made of solid gold. These were apparently stolen goods that had been taken from the grave robbers and returned by the necropolis officials without paying any further attention to the grave and its contents. According to Carter, this cleanup had been done very negligently. Howard Carter noted that the thieves must have penetrated the burial chamber into the treasury, but left the outermost shrine and thus in particular the complete royal burial untouched. The grave goods stolen by the grave robbers included precious jewelry, linen, ointments and oils. Carter interpreted this as a robbery that must have taken place shortly after the burial, since, for example, ointments and oils were not long-lasting and usable. In order to rob the treasury, he stated that despite the raid, no major damage had been done and only certain chests with valuable items had been opened. Carter concluded that the grave robbers must have been familiar with the contents of the grave. On the other hand, he concluded “that the best and most precious pieces were irretrievably lost and that he only had to deal with remains.” The grave robbers were probably involved in the king's funeral. The punishment for grave robbers and enemies of the state was impalation .

After the first robbery of the antechamber, parts of the booty found in the corridor and left behind were deposited in grave KV54 ("embalming depot") and the access to the antechamber was closed again and the necropolis was sealed. The corridor was filled with rubble to the ceiling and the breakthrough point at the entrance was closed and sealed. This made the grave more difficult to access, but did not prevent later grave robbers from entering the treasury a second time. After the discovery of the second robbery, the passages to the grave chamber and antechamber were closed, plastered and sealed, the corridor was again completely filled with rubble, the opening in the access to the grave was closed again and the steps were also hidden under rubble. The final sealing of the tomb probably took place under the rule of Pharaoh Haremhab.

Since the access from KV62 below the entrance ramp of the later laid tomb of Ramses VI. ( KV9 ) and the overburden of the Ramesside tomb and the workers' houses built on it covered access to Tutankhamun's tomb, it was hidden for thousands of years. A robbery of Tutankhamun's tomb is therefore not permitted during or after the reign of Ramses VI. (1145–1137 BC).

Location and architecture

Topographically , the Valley of the Kings ( Arabic وادي الملوك, DMG Wādī al-Mulūk ; Bibân el-Molûk ) in the west and east valleys. Most of the graves found so far are in the eastern valley , including the tomb of Tutankhamun, which is centrally located at the lowest point in the main wadi of the eastern valley. Nearby are the graves KV9 ( Ramses VI. ), KV10 , KV55 , KV56 ("gold grave") and KV63 (depot). The rock components in the Valley of the Kings are primarily limestone of various quality and sedimentary rocks . KV62 was cut in white, amorphous limestone, which is partially criss-crossed with calcite veins.

Tutankhamun's tomb with all its chambers and passages has a total size of 109.83 m². The grave of Seti I ( KV17 ) is comparatively 649.04 m², the grave of Tutankhamun's successor Eje 212.22 m² and the private grave of Tuja and Juja ( KV46 ) with a chamber, also located in the Valley of the Kings, has 62, 36 m².

Despite its smaller size compared to other royal tombs, the tomb has a floor plan that corresponds to the traditional tombs of the valley. KV62 was not built according to the royal elite measure, but according to the so-called "private elite measure". KV62 is similar to other private graves of this time in terms of the basic plan and dimensions , but is unique in this design as no similar private grave has been found so far. Contrary to the hitherto general interpretation that it is a reworked private grave, KV62 according to Nicholas Reeves is quite comparable with other royal graves. In his opinion, as already assumed by Howard Carter, this becomes clear when the plan of the tomb is rotated "in the mind" by 90 degrees.

KV62 consists of an access path (A) with 16 steps, which ended at a walled entrance (B) with the seals of the necropolis and the deceased king, followed by a further descending corridor (B) , which is also walled up (Gate I) to the next chamber ended, the antechamber. On the west wall of the pre-chamber, a further bricked, but openwork found entrance (gate Ia) , subsequent to a side chamber (Chamber Side Ia) , also known as cultivation ( Annex hereinafter) leads. The antechamber (I) is followed by the burial chamber (J) on the northern side, which was blocked from the antechamber by a walled and sealed entrance (Gate J) . Another side chamber (Ja) branches off from the burial chamber to the east and, like the antechamber, is higher than the burial chamber. This last chamber is known as the “treasury”. Apart from the burial chamber, the rest of the grave is undecorated.

Chambers and finds

Grave entrance

The stairs measure 5.61 m in length and 1.66 m in width. Various smaller objects were found while clearing the rubble. These include clay seals from the necropolis, a fragment of ivory , shards or completely preserved vessels made of stone or ceramic , fragments of wood, inventory lists for jewelry, dates on wine jugs and animal bones. Some finds could be assigned by name: a scarab of Thutmose III. , a knob with the throne name Tutankhamuns, Neb-cheperu-Re , inlays from a wooden chest with the throne and proper names ( Nefer-cheperu-Re-wa-en-Re ) Akhenaten and ( Ankh-cheperu-Re ) Neferneferuaton as well as Akhenaten and Nefertiti's first daughter, Meritaton , who here bears the title of Great Royal Wife . Akhenaten and Neferneferuaton are both named here as "King of Upper and Lower Egypt " (nisut-biti) . Howard Carter called the find the Wooden box of Smenkhkare ("Wooden box of the Semenchkare"). Carter also mentioned a fragment with the name of Amenhotep III. He was amazed at this collection of objects with the names of different people from the Amarna period , since such objects would correspond more to a “pit” than a grave entrance to a royal tomb. It was also found that of the 16 steps only the first ten had been carved into the rock, while the last six were made of stones bonded with mortar. Presumably all 16 steps were originally carved out of the rock and the last six steps before the first walling had to be removed in order to bring large grave goods, such as the gilded shrines, into the grave. After the burial, the removed steps were replaced with new ones made of a mortar and stone composite. These steps were removed again in 1930, in the 9th excavation season, so that the walls and ceilings of the last parts of the dismantled shrines that had remained since the opening of the burial chamber and in the antechamber of the grave could be brought out of the grave in their transport containers.

corridor

The first wall of the door after the 16-step staircase to the corridor was about three feet thick. The adjoining corridor is 7.67 m long and, like the stairs, 1.66 m wide and was completely cleared on the afternoon of November 26, 1922. Among other things, splinters of wood, fragments of chests and closures of various vessels, whole and broken alabaster vessels , clay seals, fragments of ivory or ivory inlays, inlays of gold and parts of gold foil were recovered from the rubble in the corridor . A find that Howard Carter did not list in his notes or in the inventory list of the entrance and corridor, but later stated the corridor as the place where it was found, is the " head of Nefertem " or "head on the lotus flower" (Egyptian Museum, Cairo, JE 60723). This bust was found in March 1924 by Pierre Lacau , the head of the antiquities administration, and Rex Engelbach , inspector of Upper Egypt , during an inventory of KV4 , the grave of Ramses XI. that was used as a warehouse while Howard Carter was not in Egypt. The "head of Nefertem" was in a red wine box between supplies. This fact led to further disagreements with the antiquities administration. Carter explained that everything that was stored in KV4 had been found in the entrance corridor, before the opening of the antechamber, and was previously listed under a group number and therefore not as a single item in the directory.

The Antechamber

The descending corridor (also the corridor) ended in front of an approx. 90 cm thick door block, behind which the 28.02 m² large antechamber is located. The walls of this chamber are roughly hewn and undecorated. In addition to the grave chamber plastered and painted with plaster, the north wall of the antechamber with the passage to the grave chamber was the only other plastered wall in the grave that was also provided with seals. On the adjoining, partly brick partition wall to the burial chamber, with a thickness of approx. 1 m, there are markings of chisels on the ceiling, which indicate that this chamber led at least two meters further north before the access to the burial chamber there was a wall was closed.

Finds in the antechamber

Along the western wall three large ritual beds (also ritual stretchers) were set up one behind the other, facing the burial chamber. Under the ritual bed of the Ammit ("Devourer of the Dead" or "Dead Eater") stood Tutankhamun's throne, made of wood, gold-plated and decorated with inlays of faience , silver, stone and colored glass . The front side of the backrest shows a scene in the style of Amarna art in which the named Ankhesenamun , the Great Royal Wife , puts on the breast ornament to the seated King Tutankhamun. Above the royal couple is the solar disk Aton , on the left and right of it two cartridges with the “didactic name of Aton” in the newer version, which was used from the 9th year of Akhenaten's reign. The god gives life to the king and queen, symbolized by the ankh at the end of the rays that end in hands. The back of the back of the golden throne, on the other hand , bears the actual birth name of the king, Tutanchaton , as well as his throne name ( Neb-cheperu-Re - "Lord of figures, a Re") and the original name of his wife, Ankhesenpaaton ("She lives through Aton / She lives for Aton ”), provided from the Amarna period .

Under the middle ritual bed of the goddess Isis-Mehtet, with the appearance of a stylized cow, about two dozen oval containers with a plaster-like surface were stacked, which contained animal food for the king's journey to the hereafter. Based on the inscriptions, this bed was assigned to the goddess Isis-Mehtet, who, however, is a lion goddess and the figure of the cow is more likely to be assigned to Hathor or Mehet-weret ("The great northern waters"). The foremost ritual bed facing the burial chamber is that of the goddess Mehet-Weret, but the chosen animal shape is not the cow corresponding to the goddess, but the lion. So the shapes and inscriptions of the two ritual beds are reversed: the bier of the lion goddess bears the inscription about the cow goddess and vice versa. There were also a large number of rolled up items of clothing, such as underclothes or kerchiefs , which Howard Carter had mistaken for papyri when he first looked into the chamber . Papyri with information on historical events were not part of a traditional grave decoration, but the Egyptian Book of the Dead or small papyri with magical formulas and sayings that were worked into the linen layers of a mummy. The latter were later found on Tutankhamun's mummy, but were so fragile that when touched they fell apart and could not be read.

In the southeast corner were four chariots, completely dismantled . A chest (find number 21) was placed between the statues on the north wall, the painted scenes of which show Tutankhamun hunting and during campaigns against Syria and Nubia . There were over 600 objects in the antechamber.

Guardian statues

The locked access to the burial chamber (J), the north wall of the antechamber, was flanked on the left and right by two black painted and gilded wooden statues, each of which was wrapped in a crumbled linen cloth, to symbolically guard the royal mummy . With the base, the "guardian statues", also known as Ka statues , measure around 1.90 m, the figures themselves have a size of around 1.72 m. According to Douglas E. Derry, who examined Tutankhamun's mummy, this corresponds approximately to the height of the king. The statue on the left of the walled-in entrance wears a so-called chat headgear (also: afnet ), the right the classic Nemes headscarf . Both figures carry the uraeus snake on their foreheads and each hold a long staff and a club in their hands. Around her neck is each one eight-row jewelry collar . The inscription on the statue with chat identifies it as the ka of the king: “The good God, before whom one bows, the ruler one is proud of, the ka of Harachte , the Osiris, the king. Lord of the Two Lands, Neb-cheperu-Re , this is justified. ”Nicholas Reeves sees, in view of the size of the statues, these as the only real portraits of the young king in the tomb. The black skin color of the figures did not serve to deter intruders. In ancient Egypt, black stood for “renewal” and the color symbolizes the Osirian aspect of the deceased king and his rebirth. For Marianne Eaton-Krauss, the positioning of the guardian statues facing each other on the north wall of the antechamber is an indubitable indication of the burial chamber behind it.

There are not many surviving, life-size depictions of an ancient Egyptian king, including three in the British Museum in London. In one of these figures, the apron is hollow and, due to the size of the cavity, was probably intended for a papyrus roll . Nicholas Reeves suspected that these figures were therefore less the guardians of the burial chamber, but rather the guardians of Tutankhamun's last secret: "The hiding place of his religious texts." A detailed examination of the statues with regard to this reference was not carried out by the antiquities administration at the time. In 2005, as part of radiological examinations of archaeological artifacts made from different materials, a Japanese-Belgian research team also published the examinations of the guardian statues in The Radiographic Examinations of the Guardian Statues from the Tomb of Tutankhamen in the International Library of Archeology. X-Rays for Archeology. One aspect was to learn something about the construction of the statues and whether papyri are or have been in the statues. The painted wooden statues were in a poor state of preservation at this point and the restoration work carried out after their discovery was still recognizable. No evidence of papyri was found. It was suggested that the other smaller figures from the tomb be examined as well.

- Finds in the antechamber

Guardian statue with Nemes headscarf , Egyptian Museum Cairo (JE 60707)

Dress bust of Tutankhamun , Egyptian Museum Cairo (JE 60722)

The grave chamber (Burial Chamber)

The floor level of the 26.22 m² grave chamber (also coffin chamber) is approximately one meter lower than that of the slightly larger antechamber. It was opened on February 16, 1923, in the presence of officials from the Antiquities Authority, Lord Carnarvon and his daughter, members of the excavation team and other guests, after the appropriate measures had been taken days beforehand: analyzing the seals on the wall and taking precautions for the objects behind hit the wall. In the upper part of the walled partition wall were the cartouches of the throne name of Tutankhamun (Neb-cheperu-Re) , while on the bottom there was only the seal of the necropolis. The burial chamber, with its more than 300 individual pieces, was completely cleared after all shrines were opened and dismantled, after about eight months by May 1925.

The hewn chamber walls are plastered and decorated. They also have small rectangular niches that vary in size. The sizes are between a height of 24 to 27 cm, a width of 16 to 20 cm and a depth of 10 to 18 cm in the rock. The small niches had been closed with a limestone slab, plastered and painted. Each niche contained a magical brick made of unfired clay, all of which, except for the brick of the west wall, were provided with sections from the Egyptian Book of the Dead (Proverbs 151 - "the four magical bricks"). They had a symbolic protective function for the royal mummy. A grave amulet or a magical figure belonged to each of the bricks. In Tutankhamun's tomb these were found in a non-typical arrangement according to the cardinal points: a small Osiris figure (east wall - facing south), a Djed pillar (south wall - facing east), the symbol of permanence and duration, an Anubis figure (West wall - facing north) and a shabti figure (north wall - facing west). A Djed pillar was usually used for the west wall, an amulet in the shape of Anubis for the east wall, a torch made of reed for the south wall and a shabti- like figure for the north wall . However, Howard Carter notes that in the New Kingdom there were often variations in the orientations of the characters as well as in the symbolism and in text copies of the Book of the Dead itself. There was also a fifth magical brick with a miniature torch and charcoal remains in the treasury on the floor in front of the Anubis Shrine . Both were replaced by the Osiris figure on the west wall. Howard Carter makes explicit reference to this fifth brick and torch in his notes. According to Zahi Hawass, this unusual fifth brick was supposed to protect the contents of the grave from robbers, as the corresponding "Spruch 151 for the secret head (mummy mask)" from the Book of the Dead , which also contains the saying for the four magical bricks, is:

- “It is I who prevents the sand from blocking the hidden, and who rejects him who rejects (himself) to the torch of the desert. I set the desert on fire, I led the way (of the enemy) astray. I am the protection of the NN "

This saying was after Lord Carnarvon's death next to the variant "Death will come to that on swift wings, which disturbs the peace of the Pharaoh." The curse of the pharaoh reproduced as another and in abbreviated form in the press: "I prevent that Sand fills the secret chamber. I am there to protect the dead. "

Finds in the burial chamber

After Howard Carter had punched a hole in the partition wall to the burial chamber and shone it with a flashlight, he saw a "wall of pure gold" that could not be explained. Only when the opening was enlarged did this “wall” reveal itself as a shrine, which thus identified the room as a burial chamber. The outermost shrine almost completely filled the burial chamber: from the shrine roof to the ceiling the free space was just over 90 cm and below 90 cm towards the north and south walls. Since the sarcophagus is not in the middle of the chamber, the distance between the shrines built above it and the west wall is smaller than that of the east wall. In the large outer gilded wooden shrine there were three other gilded wooden shrines with a wooden catafalque above them . A linen cloth decorated with daisies made of bronze lay over it . Such a cloth and the so-called "coffin rosettes" had already been found by Theodore M. Davis in grave KV55. The cloth in KV62 had suffered considerably from the weight of the decorations and, like that in KV55, was therefore crumbled and fragile. Dangling parts of it covered the offerings between the outer and third shrines. The nested shrines finally contained the stone sarcophagus with the three coffins and the mummy. There were numerous other objects between the wall and the outermost shrine and within the shrines.

Shrines

Of all four gilded wooden shrines , the first and last (viewed from the outside in) were only locked with a wooden bolt in the corresponding brackets, while the second and third shrines were found with a knotted rope and intact clay seals. The intact seals of the city of the dead ( necropolis ) showed the god Anubis in a large cartouche in the form of a reclining canid over the Nine Arches , the enemies of Egypt, and above the throne name of Tutankhamun Neb-cheperu-Re in a smaller cartouche within the large ones. In the case of the two shrines, these seals were a clear indication that no grave robber had reached the king's mummy .

All four shrines, also called coffin shrines or burial chapels, have different roofs. That of the first and exterior resembles and corresponds to the traditional shrine of Upper Egypt , per-wer . Even the canopic chest of alabaster and various wooden chests showed this form on the cover. The fourth and last shrine, on the other hand, shows the roof of the predynastic and Lower Egyptian palace shrine per-nu ("House of Flame").

The names of the first, second, third and fourth shrines go back to the order in the find situation, i.e. the outer shrine was numbered with the number 1, for example. According to the inscriptions on the shrines, the reading of the contents begins with the innermost, the fourth shrine from the inside out, with the beginning of the king's path to his immortality. The four shrines are labeled on both exterior and interior walls. Usually the walls in a royal tomb of the 18th dynasty were decorated with religious texts and representations that were supposed to enable the deceased “to pass through the underworld at night and to unite with the sun god at dawn.” This for Tutankhamun due to the The grave used in the unexpected death of the young king was too small to represent this complete "program". The four shrines with texts from the Egyptian Book of the Dead , excerpts from the pyramid texts from the Old Kingdom and the Amduat (“That which is in the underworld”) were used for this purpose. The first shrine also contains the " Book of the Celestial Cow " with the content of the annihilation of mankind as it is found later on the wall of a side chamber in grave ( KV17 ) Seti I and in grave KV62 for the first time with text in one Royal tomb is occupied. Although this content on the shrines shows parallels to conventional wall paintings and inscriptions from the 18th Dynasty, some of them are difficult to interpret. The second, inner shrine also shows the oldest known image of an ouroboros , a snake that bites its own tail end and thus forms a circle. This representation can be found once around the head and once around the feet of the representation of Tutankhamun as a mummified Osiris. The snake shown is Mehen , whose name translates as "the enveloping one".

Howard Carter noted that changes had been made to the cartridges on the second shrine, viewed from the outside, and concluded that these were from the Amarna period . Originally there was a name under the name Tutankhamun that ended in -aton . He noted that the depictions were not in the “Amarna Art Style”.

The doors of all shrines opened to the east, so that they were oriented from west to east and not, as correctly with the sarcophagus, from east to west, towards the realm of the dead. The dismantling of the shrines was sometimes difficult because, firstly, they were put together against the markings and, secondly, little care was taken and some of them had been "forcibly" put together. In two shrines, for example, there were still massive traces of work with a hammer and some parts of the gold paneling had flaked off. The reason for this installation in the burial chamber is probably that the doors could only have opened slightly or not at all if they were correctly aligned, as there was more space in the burial chamber towards the east wall.

The arrangement of nested shrines was known to the excavators from a plan for the grave ( KV2 ) of Ramses IV , which is on the Turin papyrus in 1885 , but these coffin shrines in KV62 were the first to be found in their complete execution were. Carter wrote in his excavation notes that the plan for grave KV2 would have had five shrines instead of four. A comparable shrine, which had been dismantled and badly damaged, was found in 1907 by Edward R. Ayrton for Theodore M. Davis in grave KV55 . This shrine, also made of wood and decorated with gold leaf, shows Akhenaten's mother, Queen Teje , to whom the shrine could be assigned through the inscriptions. Few parts of it are exhibited today in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo in the “Amarna Room”.

sarcophagus

Work on the west-facing sarcophagus (find number 240) began on February 12, 1924. The sarcophagus is 2.75 m long, 1.33 m wide and 1.49 m high. It is made from a single block of yellow quartzite , which has been supplemented with alabaster at the corners . The lid, on the other hand, is made of rose granite and painted to match the sarcophagus tub. It is possible that the actual lid was not finished at the time of the burial. Marianne Eaton-Krauss, on the other hand, specifies red granite as the material for the coffin tub. The lid has a massive crack in the middle, which was probably created in ancient times when it was adapted to the container. Although the crack had been closed with plaster of paris, the excavators were faced with the difficulty that the lid, weighing 1250 kg, could break through completely when lifted and thereby damage the contents of the sarcophagus.

The base of the sarcophagus is painted black. Above that, the lower decoration alternates with Djed pillars , the symbol of consistency and durability, and Isis knot , a symbol of the goddess Isis. These signs can also be found on the first and outer shrine, the Anubis shrine and the canopic shrine and are intended to protect the deceased extensively. The goddesses Isis, Nephthys (to the west), Selket and Neith (to the east) are worked into the corners as a raised relief , which embrace the dead with their wings and thus also provide protection. The upper edge of the sarcophagus is closed with a circumferential hieroglyphic inscription , the long sides each have four columns with inscriptions. The west-facing "head end" with the goddesses Isis and Nephthys is completely provided with inscriptions that can be read from the center to the left and right and relate to the goddesses. The east-facing foot end with the goddesses Selket and Neith has no associated inscriptions. At the head end of the sarcophagus lid facing west is the winged sun disk and the hieroglyphic text belonging to Behdeti (a subsidiary form of the god Horus) in the columns below, which is unique for a royal sarcophagus of the 18th dynasty. In the middle column, Tutankhamun is referred to by his throne name as "Osiris". The shape of the lid corresponds to that of the second shrine and the canopic box and the traditional shrine of Upper Egypt ( per-wer - "big house").