Impaling

The impalement is a method of execution .

history

Antiquity

In the laws of Hammurabi (LH153) staking is prescribed as a punishment for a woman who kills her husband in order to take a lover. According to Panel A of the Assyrian Law, a woman who had an abortion should also be impaled. She was also denied a normal funeral. A stele from Sennacherib orders that building owners who build their house in a Königsstrasse should be hung on a stake above their house.

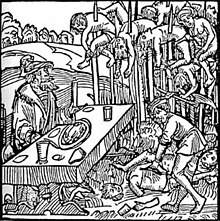

Staking and dragging of rebels is first recorded under the Assyrian king Aššur-bel-kala . In many Neo-Assyrian depictions, such as the adjacent scene from the siege of Lachish , it is not clear whether the living or the corpses were staked.

According to Herodotus (IV, 43), impalement as a punishment was also known to the Achaemenids . Xerxes had sentenced his brother-in-law Sataspes to stake for raping a virgin, the daughter of Zopyros , and pardoned at his aunt's request to circumnavigate Africa instead. When this failed, the sentence was still carried out.

Islam

From the Near East, Islamic jurisprudence adopted the punishment of impalation; however, it was rarely practiced. From the Mughal empire , the impalation of high traitors to Prince Khusrau Mirza , son of the Grand Mughal Jahangir (r. 1605–1627), has been handed down. More often the severed heads were impaled on sticks by traitors and sometimes presented to the people for years (e.g. on Jemaa el Fna Square in Marrakech ).

middle Ages

In the Middle Ages , impaling was also widespread in Europe; the people referred to it as "riding on a one-legged horse". In addition to the method of being buried alive, staking also became part of criminal law. Here, however, the convicts were killed beforehand.

In the Western European Middle Ages the convicts, often adulterers - if one can believe the legal books of the Middle Ages - were mostly buried alive and then pierced with a stake. As the legal historian Dieter Feucht suspects, this stake was not used for execution, but was intended to keep the executed person permanently underground so that he would not return to the living as an avenging revenant . In this respect, this measure is similar to staking alleged vampires . Here too - in contrast to the modern myths from novels and films - the undead was not destroyed, but merely nailed to its grave. The destruction of alleged harmful revenants or vampires was basically done by beheading and dismembering or burning the heart.

In the Middle Ages, the Eastern European variant of impalation, as used by the Romanian Prince Vlad III, was considered particularly cruel . Drăculea - largely according to the Assyrian model - is said to have practiced. This type of impalement while still alive is said to have been used by other peoples as a punishment for particularly serious crimes. The victims were mostly placed on the stake in such a way that they were impaled painfully slowly by their own body weight and the yielding connective tissue. Sometimes the stake was driven right through the whole body so that the point came out again at the top of the shoulder area. The condemned man was then hung horizontally on the stake over two forks or the like, like an animal over a fire. In some cases, a small fire is said to have been lit underneath.

Impaling was also common in Byzantium .

Modern times

A stake in Vienna has come down to us from modern times : a baker who had murdered was impaled with full consciousness in 1504.

Under the rule of the Ottoman Pasha Osman Pazvantoğlu in Vidin (1789–1807) Arnauten (Albanian mercenaries ) were impaled in front of the population to spread fear and terror. In 1800, Soleyman from Aleppo , the murderer of the French general Jean-Baptiste Kléber , was impaled in Egypt.

Literary representations

- The best-known literary description of an impalement from modern times can be found in Ivo Andrić's novel The Bridge over the Drina , which describes the execution in Bosnia in the 16th century in all gruesome details.

- In the novel The Sandelholzstrafe of Mo Yan impalement is giving title. In this work, too, there is a detailed description of the torture. Even more than Andrić , the executioner is portrayed by Mo Yan as a master of his craft, as the last master of this dying "art" during the period of the so-called Boxer Rebellion around 1900.

- The Spanish writer Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga describes in his epic La Araucana how the conquistadors put the Mapuche war chief Caupolicán to death by impaling in 1558 .

medicine

In medicine, impaling is referred to as impaling injury . This is understood as the penetration into or penetration of the body with pole-like objects. This can also happen through natural body openings or only with parts of the body. Examples are the cases of Gregor Baci from the 16th century, whose head was pierced by a tournament lance, or of Phineas Gage , whose head was pierced by an iron bar when detonated. In dogs, the stick injury is a common impalement injury.

Animal kingdom

Some species of birds are known to impale their prey. The red- backed shrike, which also occurs in Central Europe, does this to stock up on supplies.

See also

literature

- Dieter Feucht: Pit and pile. A contribution to the history of German execution customs . Verlag Mohr, Tübingen 1967 (Legal Studies; Vol. 5)

- Paul Fischer: Punishments and protective measures against the dead in Germanic and German law . Nolte, Düsseldorf 1936 (Bonn, legal dissertation of July 10, 1936)

- Ernst A. Rauter: Torture in the past and present. From Nero to Pinochet . Eichborn Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 1996, ISBN 3-8218-0806-3 (former title "Torture Lexicon. The Art of Delayed Human Slaughter from Nero to Westmoreland")

- Sigmund Stiassny: The impalation. A form of the death penalty. Cultural and legal history study . Manz, Vienna 1903.

- Martin Zimmermann (Ed.): Extreme forms of violence in images and text in ancient times . Herbert Utz Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 3-8316-0853-9 .

Web links

- Klaus Koenen: Impalation. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Fischer Weltgeschichte, Die Altorientalischen Reiche II, Frankfurt 1966, 98).

- ^ Daniel David Luckenbill : The annals of Sennacherib. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1924, p. 153. ( The University of Chicago Oriental Institute publications. 2). ( Digital version of the Oriental Institute ; PDF; 6.3 MB).

- ^ Seth Richardson, Death and Dismemberment in Mesopotamia: dsicorporation between the body and the body politic. In: Nicola Laneri (Ed.), Performing Death. Chicago 2007, 197

- ^ Dieter Feucht: Pit and pile. A contribution to the history of German execution customs . Verlag Mohr, Tübingen 1967 (Legal Studies; Vol. 5).

- ↑ Franz Grabler (Ed.): Adventurers on the Imperial Throne. The reign of Emperor Alexois II, Andronikos and Isaak Angelos (1180–1195) from the historical work of Niketas Choniates . Byzantine Historians Volume 8, 1958.

- ^ Marie-Janine Calic: Southeast Europe . Munich 2016, p. 226 .

- ↑ Entry on impaling violation in Flexikon , a Wiki of the DocCheck company , accessed on December 19, 2006.

- ↑ Leroy H. Banicki, Prey-Impaling by Black-Billed Magpie. The Southwestern Naturalist 32/2, 1987, p. 283