Vlad III. Drăculea

Vlad III. (* Around 1431 reportedly in Sighisoara ( Romanian Sighisoara ); † at the turn of 1476 / 1477 ) was 1448, 1456-1462 and 1476 Voivod of the Principality of Wallachia . His nickname Drăculea ( German "The Son of the Dragon" from Latin draco - "Dragon") is derived from the thesis most commonly accepted by historians that his father Vlad II. Dracul was a member of the Dragon Order of Emperor Sigismund . The dragon was also featured in the voivodic seal. This epithet was sometimes understood as "son of the devil", since the Romanian word drac also means devil.

Vlad III gained historical fame. on the one hand by his resistance against the Ottoman Empire and its expansion in the Balkans , on the other hand because of the cruelty it was said to be. In pamphlet-like prose stories of the 15th century, he is portrayed in an agitatory, political-polemical way, for example as a human butcher who had “dy ungen Kinder praten”. He is said to have had a preference for executions by impalation , which in Christian areas posthumously, around 1550, earned him another nickname: Țepeș [ˈtsepeʃ] ( German "Impaler" ), although he was previously owned by the Ottomans Kaziklu Bey for the same reason or Kaziklı Voyvoda (same meaning).

The originally politically motivated legends about alleged atrocities committed by the voivode found widespread use during the 15th and 16th centuries, especially in Germany and Russia. So Vlad III. also inspired the Irish writer Bram Stoker for his fictional character Dracula .

Life

There are claims that Vlad III. was born in Transylvanian Sighișoara of the then Kingdom of Hungary around 1431 as the second son of Vlad II Dracul and Princess Cneajna from the Principality of Moldova . He had two brothers, Mircea II and (as a half-brother) Radu cel Frumos ( German Radu the beautiful ).

The boyars of Wallachia supported the Ottoman Empire and subsequently deposed Vlad II as voivode of the principality, who then lived with his family in his Transylvanian exile . In the year of the birth of Vlad III. his father stayed in Nuremberg , where he was accepted into the Dragon Order . At the age of five, Vlad III. have been introduced into the order.

Hostage of the Ottoman Empire

Both the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottoman Sultan Murad II put considerable pressure on Vlad II. The border regions of the Kingdom of Hungary and semi-autonomous Wallachia had been threatened by Turkish invasion since the 1430s. Vlad Dracul finally submitted to the Sultan as a vassal and left his two younger sons Vlad and Radu as pledge, who were held in the fortress of Egrigöz , among other places .

The years as a Turkish hostage shaped the personality of Vlad III; He is said to have been flogged several times during his hostage detention for his stubborn and stubborn behavior and to have developed a strong aversion to his half-brother Radu and the later Sultan Mehmed II . The relationship with his father was likely to have been disturbed from then on, because he had used him as a bargaining chip and, through his actions, had broken the oath on the Order of the Dragon, which obliged him to resist the Turks.

Brief rule, exile and renewed takeover

In December 1447, insurgent boyars carried out a fatal assassination attempt on Vlad II in the swamps near Bălteni . The Hungarian regent Johann Hunyadi ( imperial administrator from 1446 to 1453) allegedly was behind the assassination . Vlads III. older brother Mircea had previously been blinded by his political opponents in Târgovişte with glowing iron bars and then buried alive. The Turks invaded Wallachia to secure their political power, overthrew Vladislav II from the Dăneşti clan and set Vlad III. to the throne as head of a puppet government . His reign was only brief, as Johann Hunyadi invaded Wallachia and Vlad III. discontinued in the same year. He first fled to the Carpathian Mountains and then to the Principality of Moldova and remained there until October 1451 under the protection of his uncle Bogdan II.

Petru Aron committed a fatal assassination attempt on Bogdan II in 1451 and succeeded him as Petru III. on the throne of the Principality of Moldova. Vlad III. dared the risky escape to Hungary, where Johann Hunyadi was impressed by Vlad's detailed knowledge of the Turkish mentality and the structures within the Ottoman Empire as well as his hatred of the new Sultan Mehmed II. Vlad was pardoned, made Hunyadi's advisor and over time developed into the preferred candidate for the Wallachian throne by Hungarians. 1456 pulled Hunyadi against the Turks in Serbia and at the same time Vlad III. entered Wallachia with his own troops. Both campaigns were successful, but Hunyadi died of the plague . It was the second time that Vlad ruled his homeland.

Main reign (1456–1462)

After 1456, Vlad spent most of his time at the court of Târgovişte, occasionally in other cities such as Bucharest . There he dealt with bills, received foreign ambassadors or presided over judicial proceedings. On public holidays and at public festivals he made public appearances and went on excursions to the extensive princely hunting grounds. He made some structural changes to the palace in Târgovişte, of which the Chindia tower still testifies today. He strengthened some castles, such as Poenari Castle , near which he also had a private residence built.

In the early years of his reign, Vlad eliminated rival boyar nobles or limited their economic influence to consolidate his power. The key positions in the council, traditionally in the hands of leading boyars, were mostly occupied by insignificant or foreign loyalists to Vlad. Even less important positions remained the old-established boyars now denied and were to knights beaten free peasants occupied. In 1459, Vlad had renegade boyarian nobles and clergy arrested; the older ones were impaled and their belongings were distributed among the people, the rest were forced to march about 80 km to Poienari in order to rebuild Poenari Castle on the Argeș River .

The Wallachian nobility had good political and economic relations with the cities of the autonomous region of Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons who lived there . Furthermore, in a contract signed with the Hungarian King Ladislaus Postumus in 1456, Vlad committed himself to paying tribute, for which he was assured the support of the Saxon settlers in the fight against the Turks. Vlad refused to pay the tribute for allegedly unfulfilled duties, and as a result the Hungarian-backed Transylvanian cities rose up. Vlad revoked their trading privileges and carried out raids on the cities, during which he (according to a description by Basarab Laiotă cel Bătrân from 1459) had 41 traders from Kronstadt (now Brașov ) and Țara Bârsei staked. He also picked up around 300 children, some of whom he staked and the others cremated.

After the reign of Alexandru I Aldea , which ended in 1436 , the line of the Basarab family had divided into the Dăneşti and the Drăculeşti , both of which raised claims to the throne. Some of Vlad's raids on Transylvania served to capture aspirants to the throne from the Dăneşti family. Dăneşti died several times at Vlad's own hand, including his predecessor Vladislav II shortly after taking power in 1456. Another Dăneşti was accused of participating in the live burial of Vlad's brother Mircea and is said to have been forced to kneel in front of his own grave before his execution to hold his own obituary. Thousands of Transylvanians are said to have been impaled as punishment for giving shelter to opponents of Vlad.

After the death of Vlad's grandfather Mircea cel Bătrân ( German Mircea the Elder ) in 1418, “anarchic” conditions prevailed in Wallachia at times. The ongoing state of war had led to increasing crime, falling agricultural production and severe impairment of trade. Vlad relied on tough measures to restore order, since in his eyes only an economically stable country had any chance of success against its foreign policy enemies.

During his time as a Turkish hostage, Vlad had got to know staking, which was also known in Europe for the execution of enemies and criminals. In front of the cities, the dead bodies often decay on their stakes as a deterrent against thieves, liars and murderers. According to Wallachian lore, crime and corruption should have largely disappeared soon after Vlad took office and trade and culture flourished again due to Vlad's severity. Many subjects allegedly revered Vlad for his relentless insistence on law, honesty and order. He was also known as a generous patron of churches and monasteries, as in the case of Snagov Monastery .

Vlad's "crusade"

prehistory

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II considered further campaigns. The Greek Empire of Trebizond in Anatolia still resisted the Ottoman Empire, and in the east Uzun Hasan , ruler of the Turkmen Empire of the White Mutton, along with other smaller states, threatened the Porte . In the west there was unrest in Albania under Prince Skanderbeg , and Bosnia was at times reluctant to pay the required tributes. Wallachia controlled their side of the Danube . For Mehmed, the river was of strategic importance because the other side could embark troops from the Holy Roman Empire via it .

On January 14, 1460 Pope Pius II called another crusade against the Ottomans, which was to last three years. However, only Vlad as the only European leader could be enthusiastic about this plan. Mehmed used the occidental indecision for the offensive and took with Smederevo the last independent Serbian city. In 1461 he persuaded the Greek despotate Morea and soon afterwards also the capital Mistra and Corinth to give up without a fight. Vlad's only ally Mihály Szilágyi , a brother-in-law of Hunyadi, was captured by the Turks in Bulgaria in 1460 ; his followers were tortured to death. In 1460, Vlad again entered into an alliance with the new Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus .

Mehmed's ambassadors demanded the payment of the outstanding tribute of 10,000 ducats since 1459 and a boy picking of 500 boys who were to be trained as janissaries . Instead of complying with the request, Vlad had the embassy killed. Other Turks were apprehended and impaled on Wallachian territory after crossing the Danube . In a letter dated September 10, 1460, he warned the Transylvanian Saxons in Kronstadt of Mehmed's plans for invasion and solicited their support.

In 1461 Mehmed invited the prince to negotiate the ongoing conflict in Constantinople. At the end of November 1461, Vlad wrote to Mehmed that in his absence from Hungary there would be a danger of a military strike against Wallachia, which is why he could not leave his country, and that he could not pay the toll for the time being because of the costs of the war against Transylvania. He promised payments in gold and in due course offered a visit to Constantinople. The sultan should provide him with a pasha as a deputy for the time of his absence .

In the meantime, details of Vlad's alliance with Hungary had been leaked to Mehmed. Mehmed sent Hamza Pasha from Nicopolis on a diplomatic mission to Vlad, but with the order to seize Vlad and bring him to Constantinople. Vlad learned of these plans early on. To get there, Hamza, accompanied by a 1,000-strong cavalry unit , had to pull through a narrow gorge near Giurgiu , where Vlad launched a surprise attack from an ambush and was able to destroy the Turkish armed forces. After this attack, Vlad and his cavalrymen advanced in Turkish disguise to the fortress at Giurgiu, where Vlad ordered the guards in Turkish to open the gates. Through this ruse, Vlad's troops got inside the fortress, which was destroyed in the ensuing fighting.

In his next step, Vlad crossed the frozen Danube with his army and invaded Bulgaria. Here, Vlad divided his army into several smaller units and devastated large parts of the area between Serbia and the Black Sea within two weeks , which should make it difficult to supply the Ottoman army. Vlad informed the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus in a detailed letter dated February 11, 1462 that 23,883 Turks and Muslim Bulgarians had been killed by his troops during the campaign, not counting those who were burned in their houses. Bulgarian Christians, however, were spared; many of them would have settled there in Wallachia. In view of this success, Vlad asked the Hungarian king to join him with his troops in order to fight the Turks together.

Mehmed learned of Vlad's campaign during his siege of Corinth and then detached an 18,000-strong army under the command of his Grand Vizier Mahmud Pasha to the Wallachian port of Brăila , with the order to destroy it. Vlad's army attacked the Turkish troops and decimated them down to 8,000 men. These military successes of Vlad were greeted with joy by the Transylvanian Saxons, the Italian states and the Pope alike. After this further failure of his troops, Mehmed broke off the siege off Corinth in order to confront Vlad himself.

War preparations

Ottoman side

Sultan Mehmed sent envoys in all directions to assemble an army similar in size and heavily armed to the one he had deployed in the siege of Constantinople. Estimates vary between 90,000, 150,000, 250,000, 300,000 and 400,000 men, depending on the source. In 1462 Mehmed set off with this army from Constantinople in the direction of Wallachia, with the aim of annexing them for the Ottoman Empire. Vlad's half-brother Radu proved to be a willing servant of the sultan and commanded 4,000 horsemen. In addition, the Turks carried 120 cannons , engineers and workers to build roads and bridges, Islamic clergymen such as ulema and muezzins, and astrologers who were involved in decisions. The Byzantine historian Laonikos Chalko (ko) ndyles (also: Chalco (co) ndyles) reported that the Danube traders were paid 300,000 gold pieces for the transport of the army. In addition, the Ottomans used their own fleet of 25 triremes and 150 smaller ships to transport the army, their equipment and provisions.

Wallachian side

Vlad called for the support of the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus. In return, he offered to convert from the Orthodox to the Roman Catholic faith. In response, however, he received only vague promises and looked to a general mobilization compelled that included not only men of military age, but also women, children 12 years and one of Roma existing slaves squad . Various sources cite a number of between 22,000 and 30,900 men for his armed forces. A letter from Leonardo III. According to Tocco , prince of the despotate of Epirus from 1448 to 1479, the Turkish army was 400,000 and the Wallachian army 200,000 strong. However, this figure seems excessive. Vlad's army consisted mostly of peasants and shepherds and only a few horsemen who were armed with lances , swords , daggers and chain mail. Vlad's personal guard consisted of mercenaries of various origins, including " gypsies ". Before the clashes, Vlad is said to have told his men in a speech that "anyone who thinks of death should not follow it".

Fighting

The Turks first tried to disembark in Vidin , but were pushed back by arrows hailing at them. On the night of June 4th, however, the Turks managed to land a large contingent of Janissaries near Turnu Severin on the Wallachian side of the Danube. The Serbian-born Janissary Konstantin from Ostrovitza describes the following events in his memoirs of a Janissary :

“ When night had come, we sat in the [80 prepared] ships and drifted quickly downstream, so that neither oars nor human voices could be heard. We reached the other bank about 100 paces below where their army lay. There we enclosed ourselves with a moat and wall, brought the guns into position, surrounded ourselves with shields and planted spears around us so that the [enemy] cavalry could not harm us. Then the ships drove back to the other side and all the janissaries crossed over to us.

We got into battle formation and slowly advanced ... against the enemy army. When we were quite close, we stopped and set up the guns. But by the time it came to that, they had already killed us 250 Janissaries with their guns. [...] When we saw that so many of us were dying, we quickly got ready (shot), and since we had 120 howitzers, we immediately fired several times, and we succeeded in driving their whole army from the place. . […] Then the Sultan himself crossed over to us with his entire force and gave us 30,000 gold pieces, which we distributed among ourselves. "

Vlad, who had not been able to prevent the transfer of the Ottoman army, now retreated inland, leaving only scorched earth behind. In order to hinder the Ottoman army chasing him, Vlad had pitfalls covered with wood and scrub dug and water bodies poisoned, smaller rivers diverted and in this way large stretches of land turned into swamps. The population and herds of cattle were evacuated into the mountains, so that Mehmed moved forward for seven days without meeting humans or animals or being able to take food, which made his army considerably exhausted and demoralized.

During this time, Vlad and his cavalry worried the advancing Turks with permanent attacks, mostly ambushes. According to the sources, the voivode also sent people suffering from leprosy , tuberculosis and plague to the Turkish camp so that they could become infected with these diseases. The plague actually spread through the Ottoman army. The Turkish fleet carried out a few smaller attacks on Brăila and Chilia , but without being able to cause major damage, as Vlad had already destroyed most of the important ports in Bulgaria himself. Chalcondyles wrote that the Sultan had offered a captured Wallachian soldier money for information that the latter refused to reveal even after being threatened with torture. Mehmed praised the soldier and stated: "If your master had more soldiers like you, he could conquer the world in a short time!" The Turks continued their advance to Târgovişte, but they did not succeed in the Bucharest fortress and the fortified island Take Snagov.

On June 17, Vlad carried out a night attack on the Turkish camp south of Bucharest with 24,000 (other sources speak of 7,000 to 10,000) horsemen of his troops. Chalcondyles reports that before the battle, Vlad had disguised himself as a Turk and gained access to the enemy camp and was thus able to spy out the location and the sultan's tent. Nicolaus Machinensis, Bishop of Modruš and papal envoy to the Hungarian royal court, described the events as follows:

“ The Sultan besieged Vlad at the foot of a hill that the Wallachians benefited from because of their position on the hill. Țepeș had holed up there with his 24,000 willingly following troops. When Țepeș realized that he would either die of starvation or fall into the hands of a cruel enemy and that both circumstances were unworthy of a warrior, he called his men together and explained the situation to them and was able to convince them so easily to the enemy camp to attack. He divided his troops into groups in which they would either die on the battlefield with glory and honor or, if they were right, they would take excellent revenge on the enemy. "

“ He used some Turkish prisoners who had unwisely strolled around in the twilight and who were caught in the process, to break into the Ottoman camp with some of his troops at nightfall. During that night he hurried in all directions with lightning speed and slaughtered his enemies. Had the other Wallachian commanding officer, who was entrusted with the remaining troops, been equally intrepid, or if the Turks had not followed to the full the sultan's repeated orders not to leave their posts, the Wallachian would undoubtedly have won the greatest and most splendid victory . "

“ But the other commander (a boyar named Galeş) did not dare to attack the camp from the other side as agreed. Țepeș carried out an incredible massacre without losing many of his men in this significant encounter, but many were wounded. He left the enemy camp before dawn and returned to the hill from which he had come. Nobody dared to pursue him because he had spread such an uproar and terror. I learned from questioning those who took part in the battle that the Sultan had lost all confidence in the situation. That night he had given up the camp and fled shamefully from there. He would have kept running if he hadn't been reprimanded and brought back by his friends, almost against his will. "

The attack began three hours after sunset and lasted until four the next morning. The attack had caused great confusion in the Turkish camp. Buglers are said to have sounded the attack, the battlefield was lit by torches, and the Wallachians are said to have launched several attacks in a row. Sources are divided on the success of this attack, some speak of large, others only of minor Turkish losses. However, due to the Wallachian attack, the Ottoman army lost many horses and camels. Some chronicles blame the boyars Galeş for the failure of the Wallachian operation. He had led a simultaneous attack with a second army, but is said to have been “not brave enough” to cause “the expected devastation among the enemy”. Vlad himself turned with parts of his cavalry in the direction of the tent in which the sultan was suspected. It turned out, however, that it was the tent of the Grand Viziers Ishak Pasha and Mahmud Pasha. The Janissaries, under the command of Mihaloğlu Ali Bey , eventually pursued the withdrawing Wallachians, killing 1,000 to 2,000 of them. According to the description of the chronicler Domenico Balbi , the losses on the Wallachian side totaled 5,000 men, and 15,000 men on the Ottoman side.

Despite the low morale among the Turks, Mehmed decided to besiege the capital. However, upon arrival he found the city deserted. According to chroniclers, the Turks found a “real forest with stakes”. For half an hour, the Ottoman army is said to have passed around 20,000 impaled Turkish prisoners and Bulgarian Muslims. Among them was Hamza Pascha's decaying body, which had been staked on the highest wooden stake, which was to symbolize his high-ranking position. Other sources report that the city was defended by soldiers and that staked bodies were scattered outside the city walls for a radius of 60 miles. Chalcondyles wrote of the sultan's reaction:

“ The Emperor was so overwhelmed by the picture he saw that he could not take this land from the man who could do such things and exercise control over his subjects. A man who had accomplished this would certainly be called to greater things. "

Mehmed ordered a deep trench to be dug around the Turkish camp to prevent the Wallachians from entering. The following day, June 22nd, the Turks began to withdraw. On June 29th, the Ottoman troops reached the city of Brăila and burned it down. Then they left the country with their ships for Adrianople , where they arrived on July 11th. A day later, celebrations were held on the occasion of the great victory over Vlad. The Turks had enslaved many of the inhabitants of the war zone and brought them south along with 200,000 cattle and horses.

Meanwhile, Vlad's cousin Ștefan cel Mare, the ruler of the Principality of Moldova, had tried to take Akkerman and Chilia. In the course of his attack on Chilia, however, 7,000 Wallachians rushed to successfully defend the city, with Ștefan cel Mare being wounded in the foot by artillery fire.

consequences

Vlad had been able to successfully assert himself militarily against an overpowering Turkish opponent, but he had to accept a largely devastated country for this. It was clear to political observers that the Sultan would not accept this renewed disgrace. Another campaign against Wallachia was only a matter of time. In this situation, it was not difficult for Vlad's half-brother Radu, who had converted to Islam, to convince the Wallachian aristocrats, from whom Vlad had already largely alienated himself, of the advantages of submission and tribute payments to the Sultan and thus to win them over to his side. In August 1462, Radu and the Porte agreed on a change of power in Wallachia, after which Radu led a Turkish army against the rebuilt Poenari Castle . Vlad was able to escape to Transylvania and then went into the care of the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus. He imprisoned Vlad for twelve years in the fortress of Visegrád on the grounds that Vlad had written a letter to the Sultan asking for forgiveness and an alliance against Hungary. The literature speculates that Matthias Corvinus wanted to get rid of his annoying competitor Vlad in this way, who threatened to dispute his leading role as a fighter against the Turks. In 1474 Vlad was released from custody and married to one of Matthias Corvinus' cousins, presumably after Vlad converted to Catholicism . Vlad received a military command and took Bosnian towns and fortresses with a Hungarian army, with 8,000 Muslims reportedly being impaled.

Ștefan cel Mare used the weakness of the neighboring state and took Chilia and Akkerman. Between 1471 and 1474, Ștefan invaded Wallachia several times in order to free it from the Ottoman sphere of influence. This did not succeed, however, because the voivodes employed could not withstand the Ottoman pressure. The strong Ottoman garrison in the city of Giurgiu was only 6-8 riding hours away from Bucharest . In order to put an end to the repeated attacks from the north, Sultan Mehmed II ordered an attack on the Vltava in 1475, but Ștefan defeated the approximately 120,000 invaders with his own army of only 40,000 at Vaslui . The Turkish chronicler Seaddedin spoke of an unprecedented defeat for the Ottomans. After this victory, Stefan tried to mobilize the European powers against the Ottomans, but without success.

Vlad III. and Ștefan allied and in 1476 conquered Wallachia together with Hungarian troops within a few weeks. In November, Vlad III. again and for the last time proclaimed Prince of Wallachia. Shortly after the departure of the Hungarian and Moldovan troops, Vlad was overthrown in December 1476 and had to flee with his 200-strong Moldovan bodyguard. At the end of 1476 or beginning of 1477 he either fell in battle or was murdered while fleeing. His head, soaked in honey, is said to have been brought to the Sultan as a present to Constantinople and there put on a pole for display. His body is said to have been buried in the Snagov Monastery and later moved from there to an unknown location.

Vlad's brother Radu had died in 1475. Basarab Laiotă cel Bătrân ( German Basarab Laiotă the Elder ) followed as ruler of Wallachia .

Marriages and offspring

Vlad was married to a Transylvanian noblewoman whose name has not been passed down. This marriage came from the son Mihnea I. cel Rău ( German Mihnea the Evil , * around 1462, † 1510 and from 1508 to 1509 ruler of the Principality of Wallachia ).

In his second marriage, Vlad was married to Ilona Szilágyi, a cousin of the Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus. From this marriage came a son named

- Vlad and

- another son († around 1482), whose name has not been passed down.

Etymology of the name

The name Drăculea (or Dracula ) derives from the surname Dracul according to a thesis that was first formulated in 1804 in the fourth volume of Johann Christian Engels History of the Hungarian Empire and its neighboring countries and is still accepted by most historians today from, which his father Vlad II is said to have received after his acceptance into the Dragon Order. The dragon is also found in the order's insignia that it brought with it. Dracul is composed of drac for "dragon" (Greek / Latin drako / draco , old Slavic drak ) and the Romanian suffix ul . By adding the genitive ending -a it becomes "Dracul's son". Since the dragon in the Christian-Occidental culture always symbolizes the evil that is to be overcome, it is highly unlikely that Vlad II gave himself this name. Even a positive connotation of dracul in the sense of “devil guy ”, as it can be proven in Romanian, cannot be assumed for the deeply religious late Middle Ages.

Another possible interpretation of the name is based on the voiced spelling of the Slavic-Romanian name Dragul , which can be traced in today's Romania even before the establishment of the Dragon Order. “ Drag ” in both languages means something that is dear, precious or noble. “ Dragul meu ”, for example, can be translated from Romanian as “my darling”, the Croatian / Serbian / Bosnian “ dragulj ” means “jewel” or “precious stone”. Vlad Dragul would therefore be called "Vlad the love / noble". Evidence for this interpretation can be found in a Hungarian source from 1549, in which the name of the " brave Prince Dragula " was interpreted as a diminutive of " Drago " and the Latin translation for it was " Charulus " (Latin carus = "dear") was suggested. Also Vlad III. in the last year of his life signed certificates under the names " Wladislaus Dragwlya " and " Ladislaus Dragkulya ". The assumption that Vlad II. Dragul was called and that name in connection with the emblem of the Dragon Folk etymology as "the dragon" was and interpreted as "the devil", subsequently, is thus very plausible . The voiced g would have mutated into the voiceless k and the formerly value-free variant of the name would have been "demonized". As Vlad III. was in Hungarian captivity, his reputation seems to have been so bad that only the evil variant of his name was paid attention to anyway. Accordingly, the Byzantine chronicler Dukas reports that the Wallachian voivode is evil and insidious, according to his name " Dragulios ". In the German-speaking area, the evil name variant appeared from the beginning, here Vlad III. already referred to in a chronicle written in Konstanz before 1472 as " tüffels sun ", ie as "son of the devil".

Legends and Myths

Cultural heritage

In addition to historically relevant sources, oral traditions and pamphlets with stories provide another important source about the life of Vlad III. Romanian, German and Russian legends all have their origins in the 15th century and provide additional information about Vlad III. and his relationship with his subjects.

Oral traditions have been passed on as stories and tales from one generation to the next since the 15th century. Through the continuous telling, these stories have developed a momentum of their own through subjective interpretation and individual condensation. The stories, which appeared as pamphlets, were published shortly after Vlad's death, first in Germany and then in Russia; partly for broad entertainment, partly to achieve political goals, and were shaped by local and mainly political prejudices. The pamphlets were published over a period of approximately thirty years.

Many of the stories that appeared in the pamphlets can be found in the Romanian oral tradition. Despite a generally more positive portrayal of his person, the Romanian oral tradition also describes Vlad as exceptionally cruel and often a capricious ruler. Vlad Țepeș was considered a fair prince among the Romanian peasantry, who defended his subjects from foreign aggressors such as the Turks or German merchants, and as an advocate of the common man against the oppression of the boyars. Vlad is said to have invited boyars to the feast and offered them plenty of wine. While drunk, he is said to have deliberately elicited their opinion about him and information about the machinations and corruption of the well-known boyars. As a result, those who incriminated themselves and those who were incriminated were reportedly impaled. Vlad Drăculea was valid in his country and is still considered a fair opponent of corruption in Romania.

The general flow of the stories is very similar, although the different versions differ in specific details. According to some stories, Vlad is said to have received emissaries from Florence in Târgovişte, in other stories it is said to have been Turkish emissaries. McNally and Florescu speak of different emissaries on different occasions. The manner in which they transgressed against the prince also varies from version to version. However, all versions agree on the point that Vlad had the headgear of the accused nailed to their heads because of defamation and insult , real or imaginary, probably also because of their refusal to take off their headgear in the presence of Vlad. Some narratives judge Vlad's actions as justified, others judge them as crimes with wanton and senseless cruelty.

Atrocities

The accounts of Vlad were much darker in Western Europe than in Eastern Europe and Romania. Many of the German stories about him, however, must in part be understood as politically, religiously and economically inspired propaganda . Although some of the stories have a relation to reality, most of them are pure fiction or greatly exaggerated. Furthermore, there are atrocities in western and central European history at the same time that coincide with the Vlad III. attributed cruelty are comparable.

In the West, Vlad has been described as a tyrant who gave sadistic pleasure in torturing and killing his enemies . He is said to be responsible for the deaths of 40,000-100,000 people. Numbers like these are based on information from various sources in which all alleged victims have been meticulously added up. For example, the Konstanz Chronicle reports exactly 92,268 victims for which Vlad is responsible. According to other sources, the number of victims must be given as at least 80,000, not counting those who died as a result of the destruction and burning of entire villages and fortresses. However, these numbers must be viewed as exaggerated. In one episode the impounding of 600 merchants in Kronstadt and the confiscation of their goods is described, in another document of his rival Dan III. In 1459 there are talk of 41 impalings. It is unlikely that Vlad's opponents corrected the number of victims downwards.

The German tales of Vlad's atrocities tell of impaling, torture , death by fire , mutilation , drowning , skinning , roasting and cooking of the victims. Others are said to have been forced to eat the meat of their friends or loved ones, or to have their headgear nailed to their heads. Its victims were men and women of all ages (including children and infants), religions, and social classes. A German story reports: "He caused more pain and suffering than even the most bloodthirsty tormentors of Christendom like Herod , Nero , Diocletian and all the other pagans together could imagine". In contrast, the Russian and Romanian stories mention little or no pointless violence or atrocities.

The Serbian Janissary Konstantin Mihajlović from Ostrovitza described extensively in his memoirs that Vlad often had the noses of captured Turkish soldiers cut off, who he then sent to the Hungarian court to brag about how many enemies he had killed. Mihailović also mentioned the Turks' fear of night Wallachian attacks. He also pointed out the notorious forest of stakes that allegedly lined the streets with thousands of stake Turks. Mihailović was not an eyewitness to these events, however, as he was in the rear of the Turkish army; his remarks were based on reports from soldiers at the front.

Impaling was therefore Vlad's preferred form of torture and execution . There were various methods of doing this, depending on whether the victim's death was to be quick or slow. One of these methods was to harness a horse to each of the victim's legs and gradually drive a sharpened stake through the anus or vagina into the victim's body until it emerged from the body. The much more cruel method was not to hold the end of the stake too pointed, oil it, and then set it up. While the victims impaled themselves more and more with their own body weight, the non-pointed and oiled stake prevented them from dying too quickly from shock or damage to vital organs. That stake death was slow and excruciating, and it sometimes took hours or days to come. According to other reports, victims were also impaled through the abdomen or chest , resulting in relatively quick death. Children are said to have been sometimes impaled and pushed through their mother's chest. In other cases, victims were staked upside down. Allegedly, Vlad often had the piles arranged in different geometric patterns. The most common pattern is said to have been a ring of concentric circles. The pile height corresponded to the rank of the victim. The bodies were often left to rot on the stakes for months as a deterrent.

According to contemporary reports, thousands of adversaries were also staked on other occasions, such as B. 10,000 people in Hermannstadt (Romanian Sibiu ) in 1460, and in August of the previous year 30,000 merchants and officials of the city of Kronstadt for subversive behavior towards Vlad. This report should be seen in the context that even large cities in the Holy Roman Empire rarely had more than 10,000 inhabitants in Vlad's time.

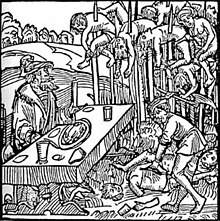

A wood engraving from this period shows Vlad at a feast in a forest of stakes with a gruesome burden, while an executioner is cutting up other victims.

An old Romanian story describes that Vlad once placed a golden bowl in the market square of Târgovişte. This bowl could be used by anyone to quench their thirst, but had to remain in the marketplace. He is said to have returned the next day to pick them up again. Nobody had dared to touch the bowl, the fear of life-threatening punishment was too great.

Vlad Țepeş is said to have carried out further impalings and torture on the advancing Turkish military units . It has been reported that the Ottoman army shrank in horror at the sight of several thousand impaled and decaying corpses on the banks of the Danube. Other reports say that the conqueror of Constantinople , Mehmed II, known for his own psychological warfare , was shocked by the sight of 20,000 impaled bodies outside the Wallachian capital, Târgovişte. Many of these victims were Turkish prisoners who had been previously captured during the Turkish invasion. The Turkish losses in this dispute are said to have amounted to 40,000. The sultan passed the command of the campaign to his officers and returned to Constantinople himself, although his army was 3: 1 outnumbered and better equipped than the Wallachian troops.

Vlad is said to have committed his first significant act of cruelty shortly after he came to power, driven by revenge and to consolidate his power: He accordingly invited the noble boyars and their families who were involved in the assassination attempt on his father and the burial of his older brother alive Mircea had been involved in celebration of Easter . Many of these nobles were also involved in the overthrow of numerous other Wallachian princes. During the feast, he asked his noble guests how many princes they had seen and survived during their life in office. All of them had survived at least seven princes, one even at least thirty. Vlad had all the nobles arrested; the older ones were impaled on the spot with their families, the younger and healthier ones were kidnapped from Târgovişte north to Poienari Castle in the mountains above the Argeş river. There they were forced for months to rebuild the fortress using materials from another castle ruin nearby. The story goes that the slave laborers toiled until their clothes fell off their bodies and then went on to work naked. Few of them are said to have survived this ordeal. During his reign, Vlad had to fight the old boyar class in Wallachia to consolidate his power.

German stories

The German narratives are based on manuscripts that were written before Vlad's imprisonment in 1462 and then spread in the later 15th century. With the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1450, the text later found widespread use in Germany and became a bestseller , with numerous editions added or the content changed.

Michel Beheim wrote the poem “Von ainem wutrich der hies Trakle waida von der Walachei” in the winter of 1463 at the court of the Hungarian King Ladislaus V of Hungary . Of the publications, four manuscripts from the last quarter of the 15th century and 13 pamphlets from the period from 1488 to 1559/1568 have survived, eight of them as incunabula . The German stories consist of 46 short stories , but there is no complete edition. All stories begin with the description of the old regent (meaning Johann Hunyadi), his murder of Vlad's father, the conversion of Vlad and his older brother from their old religion to Christianity and their oath to defend and uphold Christianity.

According to this arrangement, the episodes in the various manuscripts and pamphlets differ from one another. The titles of the stories vary in a total of three versions. The first version of the German text probably came from the pen of a scholar in Kronstadt and reflects the sentiments of the Transylvanian Saxons in Kronstadt and Sibiu, who suffered heavily from Vlad's hostilities between 1456 and 1460. The gloomy and grim depiction of Vlad, partly historically based, partly exaggerated and fictional, was therefore probably politically motivated.

Vlad's atrocities against the Wallachian people were interpreted as attempts to enforce his own code of conduct in his country. In the pamphlets, Vlad's anger was also directed at violations of female modesty . Unmarried girls who have lost their virginity ; Wives committing adultery and unchaste widows were all targets of Vlad's atrocities. Women with such misconduct often had their genital organs excised or their breasts cut off. They were also staked through the vagina with glowing stakes until the stake came out of the victims' mouths. One text reports the execution of an unfaithful wife. Her breasts were cut off, then she was skinned and staked in a square in Târgovişte, lying with her skin on a nearby table. Vlad also insisted on honesty and the hard work of his subjects. Merchants who betrayed their customers quickly found themselves next to common thieves on the stake. Vlad saw the poor, sick and beggars as thieves. One story tells of his invitation to the sick and poor to a feast during which the building that houses it was closed and set on fire.

Russian stories

The Russian-Slavic versions of the stories about Vlad Țepeș were entitled Skazanie o Drakule voevode ( German stories about the voivode Dracula ) and were written between 1481 and 1486. Copies of the stories were copied and distributed from the 15th century through the 18th century. There are 22 manuscripts in Russian archives. The oldest manuscript dates from 1490 and ends as follows: "First written on February 13th in 6994 [meaning 1486], then copied on January 28th in 6998 [meaning 1490] by me, the sinner Elfrosin" . The collection of anecdotes about the voivode Dracula is neither chronological nor free of contradictions, but of great literary and historical value. The 19 episodes of the stories about the voivode Dracula are longer and more developed than the German stories. They can be divided into two parts, with the first 13 episodes more or less depicting events in chronological order, which are based on the oral traditions and in ten cases closely on the German stories. The last six episodes are believed to have been written by a scholar. These stories are more chronological and structured in nature.

The stories about the voivod Dracula begin with a brief introduction and then move on to the story of nailing hats on the heads of ambassadors. They end with the death of Vlad Țepeș and information about his family. The German and Russian stories are similar, but the Russian stories describe Vlad in a more positive light. Here he is seen as a great master, courageous soldier and just sovereign prince. There were also stories of atrocities, but these were justified as acts of a strong autocrat. The 19 episodes contain only six sections with excessive violence. Some elements of the stories about the voivode Dracula were later added to the Russian tales about Ivan IV , also called the Terrible . The nationality and identity of the original writer of the Vlad stories is controversial. It is believed that this was a Romanian priest or monk, probably from Transylvania or from the court of Ștefan cel Mare from Moldova. Other sources cite a Russian diplomat named Fyodor Kuritsyn as the author.

Political motives

The Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus is said to have contributed to the creation of this personality image. Corvinus had received extensive financial support from Rome and Venice for the military conflict with the Ottoman Empire, which he instead used to finance his military conflict with Emperor Friedrich III. fed. Corvinus justified his absence from the war against the Turks against his financiers by making Vlad the scapegoat . Under the pretext of a forged letter in which Vlad allegedly pledged his loyalty to Sultan Mehmed II, he had Vlad arrested and benefited from the horror stories about Vlad spread from his court in Buda between 1462 and 1463 in Central and Eastern Europe.

There have been attempts to justify Vlad's actions as a political necessity because of the national rivalry between the Transylvanian and Wallachian ethnic groups. Most of the merchants in Transylvania and Wallachia were Transylvanian Saxons, who were viewed by the native Wallachians as exploiters and parasites. The merchants of German descent also made use of the hostility of the boyar families among themselves and their dispute over the Wallachian throne by supporting various pretenders to the throne and playing them off against one another. In this way, from Vlad's point of view, they, like the boyars themselves, had demonstrated their disloyalty. Last but not least, Vlad's father and older brother had been murdered by renegade boyars.

A Romanian saying that is still used today is based on the myths about Vlad III. to: “Unde eşti tu, Țepeş Doamne?” ( German Where are you, Țepeş [impaler], lord? ) is used in relation to chaotic conditions, corruption, laziness, etc. The saying is a line from a polemical poem by the poet Mihai Eminescu (1850–1889), in which the national political disinterest of the Romanian upper class is attacked. Eminescu asks his imaginary contact, Vlad, to stake half of the upper class like the boyars once did and to burn the other half in a festival hall like the beggars and drifters once did.

Vlad's passionate insistence on honesty is at the core of the oral tradition. Many of the anecdotes from the published pamphlets and oral tradition underscore the prince's restless efforts to curb crime and mendacity. During his 2004 election campaign, Romanian presidential candidate Traian Băsescu referred to the methods used by Vlad Țepeș to punish illegal acts in a discourse against corruption in his country.

The Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu , ousted in 1989, developed a particular preference for Vlad Drăculea in the 1970s and commissioned a monumental film about the Impaler ( Vlad Țepeș (1979), director: Doru Nastase). The film made Vlad III. Drăculea appear like a direct forerunner or spiritual ancestor of the dictator. The film was also shown in the GDR under the title The True Life of Prince Dracula . Although Vlad was already a myth in the 19th and especially in the early 20th century, under Ceaușescu he became an omnipresent figure in literature, in historiography and not least in school books. Romanian historians were encouraged to either play down the alleged atrocities or to praise them as proof of the strict but just rule of Vlad. Finally, even the name Dracul (a) should be reinterpreted because it means devil and not dragon in modern Romanian . With an etymology that is dubious from a linguistic point of view , the name was derived from a Slavic word root drag- , which also appears in the Serbian first name Dragan and means something like darling . Dracula was thus the little darling of his loyal subjects - an argument in the sense of Nicolae Ceaușescu, who liked to be celebrated as the beloved son of the Romanian people as part of the personality cult celebrated around himself.

On his escape from Bucharest in December 1989, the Ceaușescu couple first headed for Snagov, the alleged tomb of Vlad. The Ceaușescus were finally captured in Târgoviște, where the prince once held court. There Elena and Nicolae Ceaușescu were shot dead on December 25, 1989 after a brief trial .

Historic sites

A number of villages are associated with the Prince's name and are marketed for tourism. One example is Bran Castle ( German Törzburg , Hungarian Törcsvár ) in the village of Bran in the Brașov district (formerly Kronstadt). Historically, the fortress is still not traceable as the home of Drăculea. The name Vlad Drăculea does not appear in the eventful list of owners. Only one source mentions that the prince once stayed at Bran Castle. There is no evidence to support the claim that Vlad was born in Sighișoara (today Sighișoara) in Transylvania . The house, in which, according to Romanian travel guides, his father lived for a short time, was only built after the great fire in 1676. Nor was there a body to be found in the alleged grave of Vlad in Snagov, as was discovered when the grave was opened in 1931. Another monastery in Comana , a parish in Giurgiu County , claims to be the final resting place of Vlad's corpse. The church building at that time has not existed since 1588, as the monastery that still exists today was built at that time.

Vlad's first wife

In 1462, during the Turkish siege of the Poenari fortress, led by Vlad's half-brother Radu cel Frumos, according to legend, the first wife of Vlad (name is unknown) committed suicide. A confirmation of the story through historical documents has not yet been provided. A loyal archer is said to have shot an arrow through the window of Vlad's apartment. The shooter was one of Vlad's former servants who had been forced to convert to Islam. The arrow carried the message that Radu's forces were about to attack. After reading this message, Vlad's wife is said to have thrown herself from the castle into a tributary of the Argeș, the Râul Doamnei ( German: The Lady's River ), which runs past the castle . Her last words are said to have been that she would rather let her body rot in the waters of the Argeș or be eaten up by fish before going into Turkish captivity (slavery). This legend was filmed in Francis Ford Coppola's film Bram Stoker's Dracula , in which Dracula's wife Elisabeta takes her own life on false news of her husband's death. Dracula then curses God and is condemned to live as an undead as a punishment .

Dracula

Dracula is the title of a novel by Bram Stoker from 1897 and the name of the central figure, Count Dracula , probably the most famous vampire in literary history. When creating the figure, Stoker is said to have been given by Prince Vlad III. have been inspired. This thesis of the historians Radu R. Florescu and Raymond T. McNally, made popular in the 1970s, has been questioned by other authors. McNally suggested that the Hungarian Countess Elisabeth Báthory may have contributed to the author's inspiration.

Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller also argue that the "historical Voivode Dracula" has only a minor influence on the literary figure, since neither in the preparatory studies for Dracula nor in the novel itself of the Vlad III. atrocities ascribed to it (especially the characteristic piling). The little historical information (such as the battle of Cassova , the crossing of the Danube and the "betrayal" of his brother ) are all taken from William Wilkinson's An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia .

Dracula finally came to the collective memory through countless film adaptations of the material, especially in the depictions of Max Schreck ( 1922 ), Bela Lugosi ( 1931 ), Christopher Lee ( 1958 ), Klaus Kinski ( 1979 ) and Gary Oldman ( 1992 ). The time of the novel is the end of the 19th century.

Cinematic processing

In 2000, Dark Prince: The True Story of Dracula was released, a feature film that dealt with Vlad's life. The film is primarily based on the Romanian point of view of himself, where Vlad is portrayed as a national hero who restored order in Romania and fought against the Turks.

Sources and literature

Sources and source editions

- Thomas M. Bohn, Adrian Gheorghe, Christof Paulus, Albert Weber (eds.): Corpus Draculianum. Documents and chronicles about the Wallachian prince Vlad the Impaler 1448-1650. Volume 1: Letters and Certificates . Part 1: The tradition from Wallachia . Edited by Albert Weber and Adrian Gheorghe. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2017, ISBN 978-3-447-10212-4 . Part 2: The tradition from Hungary, Central Europe and the Mediterranean. Edited by Albert Weber, Adrian Gheorghe and Christof Paulus. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2018, ISBN 978-3-447-10628-3 .

- Thomas M. Bohn, Adrian Gheorghe, Albert Weber (eds.): Corpus Draculianum. Documents and chronicles about the Wallachian prince Vlad the Impaler 1448–1650. tape 3 : The tradition from the Ottoman Empire. Post-Byzantine and Ottoman authors . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, ISBN 978-3-447-06989-2 .

- Bukoavn: Alphabetarium of the Wallachians in Transylvania . (around 1600).

- Bartholomäus Ghotan : Van deme quaden thyranne Dracole Wyda . National Széchényi Library ( mek.oszk.hu [PDF; 7,9 MB ] not before 1488, with a Hungarian introduction).

- Sebastian Henricpetri: Wallachian War or Stories warehofte description . 1578.

- Historia How the great Mahomet, Turkish emperor, the name of the other, the famous city of Constantinople, with four hundred thousand men besieged, conquered, plundered and finally brought under his power, grew . Magdeburg 1595.

- Renate Lachmann (ed.): Memoirs of a Janissary or Turkish Chronicle (= Slavic historian . Volume 8 ). Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, ISBN 978-3-506-76842-1 (first edition: 1975, reprint of the original Graz).

- Mathiae Corvini Hungariae Regis . 1891.

- Between new zeytting, and even bigger Christian Victoria, so the Christians, with God's help and by-hand, have defeated and overcome 500,000 Turks at Ostrahitz in Croatia on October 29th, anno of the 87th year. More a new Zeyttung, except Constantinople the 27th Nov., Anno 1587. Jar, which also the Georgians and Ianitscharen, vil a thousand Turks slain on two orders . Wörly, Augsburg 1587 ( reader.digitale-sammlungen.de ).

Secondary literature

- Radu R. Florescu, Raymond T. McNally: Dracula a biography of Vlad the Impaler 1431–1476 . Hawthorn Books, 1973, ISBN 3-550-07085-3 .

- Heiko Haumann : Dracula. Life and Legend, Beck'sche Reihe 2715 . CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-61214-5 .

- Christine Klell, Reinhard Deutsch: Dracula - Myths and Truths . Styria, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-222-13302-2 .

- Peter Mario Kreuter: How Ignorance Made a Monster. Or: Writing the History of Vlad the Impaler without the Use of Sources Leads to 20,000 Impaled Turks . In: Kristen Wright (Ed.): Disgust and Desire. The Paradox of the Monster . Brill, Leiden 2018, ISBN 978-90-04-35073-1 , pp. 3-19.

- Michael Kroner : Dracula. Truth, Myth and the Vampire Business . Johannis Reeg, Heilbronn 2005, ISBN 3-937320-33-4 .

- Ralf-Peter Märtin : Dracula. The life of Prince Vlad Țepeș . Wagenbach, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-8031-2065-9 .

- Thomas Schares: Parallel word and image discourses about Vlad Țepeș (Vlad III. Draculea). In: transcarpathica. germanic yearbook romania 9 . 2010, p. 343-366 .

- Wilfried Seipel (Ed.): Dracula. Voivode and vampire. Exhibition catalog of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Ambras Castle, Innsbruck, June 18 - October 31, 2008 . Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-85497-139-9 .

- Nicolae Stoicescu: Vlad Țepeș . Bucharest 1976 (English edition 1978: Vlad Țepeș: prince of Walachia ).

- Manfred Stoy: Vlad III. Ţepeş . In: Biographical Lexicon on the History of Southeast Europe . Vol. 4. Munich 1981, pp. 420-422.

- Kurt W. Treptow: Vlad III. Dracula, The Life and the Times of the historical Dracula . Center for Romanian Studies, 2000, ISBN 973-98392-2-3 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Vlad III. Drăculea in the catalog of the German National Library

- Siebenbuerger.de , Konrad Klein: Vlad Țepeș alias Dracula: "A reddish, lean face with a threatening expression"

- Vlad III. Ţepeş , Manfred Stoy, in: Biographical Lexicon on the History of Southeast Europe. Vol. 4th ed. Mathias Bernath / Karl Nehring. Munich 1981, pp. 420-422 [online edition]

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ralph-Peter Märtin: Dracula. The life of Prince Vlad Țepeș . Wagenbach, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-8031-2065-9 , p. 155 .

- ↑ Ralph-Peter Märtin: Dracula. The life of Prince Vlad Țepeș . Wagenbach, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-8031-2065-9 , p. 9 .

- ^ Working group for Transylvania regional studies: Journal for Transylvania regional studies . tape 28 . Böhlau Verlag, 2005, p. 2 .

- ↑ Dieter Harmening: 'Drakula'. In: Burghart Wachinger et al. (Hrsg.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . 2nd, completely revised edition, Volume 2 ( Comitis, Gerhard - Gerstenberg, Wigand ). De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1980, ISBN 3-11-007264-5 , Sp. 221-223.

- ^ Thomas Garza, The Vampire in Slavic Cultures, 2010, Ed. Cognella, USA, pp. 145-146, ISBN 978-1-60927-411-5

- ^ William Wilkinson: An account of the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, Eastern Europe Collection . Arno Press, 1971, ISBN 0-405-02779-6 (English).

- ^ Alfred Owen Aldridge: Comparative literature: matter and method . University of Illinois Press, 1969, pp. 113 (English).

- ^ Kurt W. Treptow: Vlad III. Dracula, The Life and the Times of the historical Dracula. Center for Romanian Studies, 2000, ISBN 973-98392-2-3 , p. 104.

- ↑ a b Heiko Haumann : Dracula: Life and Legend (= Beck'sche series . Volume 2715 ). CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 3-406-61214-8 , pp. 33 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Radu R. Florescu, Raymond T. McNally: Dracula, prince of many faces: his life and his times . Little, Brown, 1989, ISBN 0-316-28655-9 , pp. 129-148 (English).

- ↑ Joseph Geringer: Man More Than Myth. Chapter: Staggering the Turks. crimelibrary.com ( Memento of October 4, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), in English, accessed April 18, 2011. Allegedly, the Wallachians also used hand pipes . Vlad would be another candidate among the Crusaders for the first use of firearms on the battlefield.

- ↑ a b c Nicolae Stoicescu: Vlad Țepeș, prince of Walachia, Bibliotheca historica Romaniae: Monographies . Editura Academiei Republicii Socialiste România, 1978, ISBN 0-521-89100-0 , p. 99, 107, 117-118 (English).

- ↑ a b c d e f Franz Babinger: Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time (= Bollingen series . Volume 96 ). Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-01078-1 , pp. 204-207 (English).

- ↑ a b c d Noi Izvoare Italiene despre Vlad Țepeș și Ștefan cel Mare

- ↑ This passage in square brackets does not come from the Polish version of the memoirs of a Janissary that Lachmann chose for her edition, but was inserted by her from the other surviving versions.

- ↑ Konstanty Michałowicz, Claus-Peter Haase, Renate Lachmann, Günter Prinzing: Memoirs of a Janissary: or Turkish Chronicle . Ed .: Renate Lachmann (= Slavic historian . Volume 8 ). Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1975, ISBN 3-222-10552-9 , pp. 133 f .

- ↑ Kronika Polska names 40,000 Moldavian troops; Gentis Silesiæ Annales names 20,000 Ottoman troops and “no more than” 40,000 Moldavian troops; Ștefan's letter to the Christian world of January 25, 1475 mentions 120,000 Ottoman troops; see also the annals of Jan Długosz. P. 588.

- ^ Constantin C. Giurescu, Horia C. Matei, Comisia Națională a Republicii Socialiste România pentru UNESCO: Chronological history of Romania . Editura enciclopedică română, 1972, p. 412 (English).

- ↑ a b www.ucs.mun.ca , Memorial University of Newfoundland, Elizabeth Miller: Vlad The Impaler: Brief History , 2005, accessed April 15, 2011.

- ↑ a b Wilfried Seipel (Ed.): Dracula. Voivode and vampire . Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-85497-139-9 , pp. 18, 21 and 26, notes 1, 3 and 4 .

- ^ A b c Raymond T. McNally, Radu Florescu: In search of Dracula: the history of Dracula and vampires . Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1994, ISBN 0-395-65783-0 (English).

- ↑ a b c eskimo.com , Ray Porter: The Historical Dracula , 1992.

- ↑ Vlad III. Ţepeş , Manfred Stoy, in: Biographical Lexicon on the History of Southeast Europe. Vol. 4th ed. Mathias Bernath / Karl Nehring. Munich 1981, pp. 420-422 [online edition]; accessed on May 8, 2020

- ^ Radu R. Florescu: Essays on Romanian history . Centrul de Studii Româneşti, 1999, ISBN 973-9432-03-4 .

- ↑ Wilfried Seipel (Ed.): Dracula. Voivode and vampire . Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-85497-139-9 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ a b c Dieter Harmening: The beginning of Dracula. To the story of stories . Königshausen and Neumann, 1983, ISBN 3-88479-144-3 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Ștefan Andreescu: Vlad Ţepeş . Minerva, The Romanian Cultural Foundation Publishing House, 1976, ISBN 973-577-197-7 (Romanian).

- ↑ Heiko Haumann : Dracula: Life and Legend (= Beck's series . Volume 2715 ). CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 3-406-61214-8 , pp. 42-45 .

- ↑ Arno Kreus, Rainer Beierlein, Norbert von der Ruhren: Terra Germany. Subject volume: Demographic and urban structures. Secondary . Klett, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 3-623-29710-0 , p. 70-75 .

- ^ A b William Layher, Gerhild Scholz Williams: Consuming News: Newspapers and Print Culture in Early Modern Europe (1500-1800) . Rodopi, 2009, ISBN 978-90-420-2614-8 , pp. 21 (English). , William Layher: Horrors Of The East . In: Daphnis . No. 37 / 1-2 , 2008, pp. 11-32 , doi : 10.1163 / 18796583-90001051 (English).

- ↑ Dracula and his heirs , Gunter E. Grimm , Stuttgarter Zeitung, December 31, 1985–3. January 1986

- ↑ Michel Beheim, Hans Hermann Karl Gille, Ingeborg Spriewald: The poems of Michel Beheim: After the Heidelberger Hs. Cpg 334 with reference to the Heidelberg Hs. Cpg 312 and the Munich Hs. Cgm 291 as well as all partial manuscripts . tape 60 . Akademie-Verlag, 1972. See also: David B. Dickens, Elizabeth Miller: Michel Beheim, German Meistergesang, and Dracula ( Memento from August 9, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) ( RTF ; 51 kB, English).

- ^ A b c d Raymond McNally: Origins of the Slavic Narratives about the Historical Dracula . 1982.

- ↑ Jurij Striedter: The story of the Wallachian Vojevoden Dracula in Russian and German tradition . In: Journal of Slavic Philology . tape 28 . Steiner, 1961, p. 398-427 .

- ↑ Maureen Perrie: The Image of Ivan the Terrible in Russian Folklore (= Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture . Volume 16 ). Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-521-89100-0 (English).

- ↑ Heiko Haumann : Dracula: Life and Legend (= Beck's series . Volume 2715 ). CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 3-406-61214-8 , pp. 26-30 .

- ↑ a b Sheilah Kast, Jim Rosapepe: Dracula is dead: how Romanians survived Communism, ended it, and emerged since 1989 as the new Italy . Jim Rosapepe, 2009, ISBN 1-890862-65-7 , pp. 150 (English).

- ↑ Georg Seesslen, Fernand Jung: Horror: History and Mythology of Horror Film, Basics of Popular Film . Schüren, 2006, ISBN 3-89472-430-7 , pp. 1135, here p. 54 .

- ↑ Thomas M. Meine: Alle ins Gold and other errors around the bow and arrow . BoD - Books on Demand, 2009, ISBN 3-00-029013-3 , pp. 161 .

- ^ Rudolf J. Strutz: Dracula - Facts, Myth, Novel. P. 33.

- ↑ Vlad Tepes. Ruler of Wallachia. In: Holy Monastery Comana, on manastireacomana.ro.

- ↑ Elizabeth Miller: Dracula - the shade and the shadow: papers presented at "Dracula 97", a centenary celebration at Los Angeles, August 1997, chapter: Filing for Divorce. Count Dracula vs. Vlad Tepes . Princeton University Press, ISBN 1-874287-10-4 (English).

- ↑ Elizabeth Miller: Dracula: sense & nonsense . Desert Island Books, 2000, ISBN 1-874287-24-4 (English).

- ^ Raymond T. McNally: Dracula was a woman: in search of the blood countess of Transylvania . McGraw-Hill, 1983, ISBN 0-07-045671-2 (English).

- ↑ Bram Stoker, Robert Eighteen-Bisang, Elizabeth Miller: Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula . McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, Jefferson, North Carolina 2008, ISBN 978-0-7864-3410-7 , pp. 285 .

- ^ William Wilkinson: Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia Longman, 1820.

- ↑ Bram Stoker, Robert Eighteen-Bisang, Elizabeth Miller: Bram Stoker's Notes for Dracula . McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, Jefferson, North Carolina 2008, ISBN 978-0-7864-3410-7 , pp. 245 .

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Vladislav II. |

Prince of Wallachia 1448 |

Vladislav II. |

| Vladislav II. |

Prince of Wallachia 1456–1462 |

Radu cel Frumos |

| Basarab Laiotă cel Bătrân |

Prince of Wallachia 1476 |

Basarab Laiotă cel Bătrân |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Vlad III. Drăculea |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Țepeș (Romanian); The Impaler, The Impaler |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Voivode of Wallachia |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1431 |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1476 or 1477 |

| Place of death | Bucharest |