astrology

The astrology (as Greek in the 16th century astrologia , astrology , formed from AltGr. Ἄστρον Astron , star 'and λόγος logos , teaching') is the interpretation of correlations between astronomical events or stellar constellations and ground operations. It was already practiced in pre-Christian times in different cultures, especially in China , India and Mesopotamia . "Western" astrology has its origins in Babylonia and Egypt . The basics of interpretation and calculation, which are still recognizable today, came from the Hellenistic Greek-Egyptian Alexandria . For a long time it formed a hardly distinguishable unit with astronomy .

Astrology had a checkered history in Europe. After Christianity was elevated to the status of the state religion in the Roman Empire , it was partly opposed, partly adapted to Christianity and temporarily sidelined. In the course of the early Middle Ages , astrology, especially learned astronomy astrology, revived in the Byzantine Empire from around the late 8th century, as it did a little later in Muslim Al-Andalus on the Iberian Peninsula . From the later High Middle Ages and above all in the Renaissance up to the 17th century, it was often considered a science in Europe, always associated with astronomy, even if it was quite controversial. It was only in the course of the 17th century that astronomy and astrology began to separate more strongly, and astronomy developed into a non-meaningful observation and mathematical recording of the universe, while astrology lost its plausibility in the educated circles of Europe . Around 1900 there was again a serious interest in astrology, often also in the wake of new esoteric currents such as theosophy or the occult fashion from the later 19th century. From the 20th century, the focus of "western" astrology in particular shifted to the interpretation of the human natal chart. Since the late 1960s, starting with the New Age movement, it has gained a high degree of popularity in the western hemisphere, mostly in the form of natal charts and newspaper horoscopes .

Nowadays the origin, development and manifestations of astrology are scientifically researched; For example, from a religious , ancient philological , archaeoastronomical , ethological , cultural , mathematical , medical and scientific-historical perspective, often also interdisciplinary .

Since the 1960s, statements by astrologers in western cultures have increasingly been examined empirically and scientifically. The results of all methodically correct checks show that the verified statements are not statistically significantly better than arbitrary claims.

term

Today's strict separation of astronomy / astronomia and astrology / astrologia did not exist until late antiquity. Both terms could mean the interpretation of the alleged effect of the celestial bodies on the so-called sublunar sphere , i.e. the earth, or the observation of the sky for the purpose of recording and researching the movements of the celestial bodies. Correspondingly, the astrological aspects of astronomy found interest and recognition among ancient astronomers such as Ptolemy or Hipparchy , which in astrological studies with significantly decreasing acceptance remained so in some cases until the end of the 17th century. When the separation between scientific astronomy and unscientific astrology was finally completed is controversial. The philosopher Siegfried Wollgast names the second half of the 17th century, the classical philologist Stephan Heilen calls it the Age of Enlightenment , according to Kocku von Stuckrad , the process was ultimately only completed in the 19th and 20th centuries.

In ancient times , astrology first emerged as mouth astrology ; since Hellenistic astrology areas who came before the birth of Christ natal astrology , the Katarchen horoscopes for the best time of a public or private action-launch as well as the so-called theme mundi , to a kind of "Ur Horoscope" for the legendary time of world creation. Today, astrology is usually only understood to mean the natal chart.

Underlying worldviews

Until the 18th century, astrology was often based on the assumption that there was a physical connection between the positions and movements of planets as well as stars and earthly events, often under the term "natural astrology", which for example related to the weather that should work in agriculture and medicine. On the other hand, which is far less clearly understood from a physical point of view, there was especially natal astrology with its effects on people's lives, which often claimed to be able to predict future developments in human life and which, in its interpretations, were often real or supposed Repeated long-standing, far-reaching astrology experiences. This is the case with natal astrology and the like. a. back to the idea of macrocosm (universe) and microcosm (earth or human), which are thought of as a unit related to one another. The human being as a microcosm is a mirror of the macrocosm, there is a correspondence between the human body and parts of the cosmos, and thus a system of mutual dependencies between the parts of the cosmic organism. Some assume that the macrocosm has a direct effect on the microcosm (effect theory), while others believe only in a reflection (symbol theory). "As above, so below", as it is called in the Hermetic Tabula Smaragdina . This worldview is of a religious nature in the broader sense.

In today's western astrology, four views of the nature of astrological statements can be distinguished. The esoteric astrology refers to an advised by divine beings or "initiated" knowledge. Symbolic astrology presupposes a traditional system of interpretation in which astronomical conditions are assigned a meaning in relation to earthly ones. In addition, an "astrology as empirical science" is represented, which endeavors to establish an empirical basis, and finally there is the influence hypothesis, according to which the astrological planets affect living beings in a way that has not been known so far.

Scientific theory classifications

From an epistemological perspective, astrological teachings, as they emerged in the course of antiquity in the eastern Mediterranean and the Orient , can be viewed as protoscience . Since Hellenism they have increasingly been based on the physics of Aristotle , that celestial bodies - the supralunar sphere - exert a direct influence on the sublunar world area of the earthly atmosphere with the four elements and thus cause events. Before that, astrologers-astronomers had started from about the fifth to fourth century BC to develop more and more mathematical models and calculations in order to show regularities in observable natural phenomena and to be able to calculate them in advance. Since the point in time played a decisive role, detailed tables had been created for centuries in order to predict the occurrence of certain events, since the corresponding calculations were not yet in a position. To determine the position and orbit of planets were z. Sometimes complex calculations with the help of geometry and trigonometry are necessary. Therefore, these practices are not superstitions , but an early form of science. The search for regularities in natural phenomena and their comprehensive description in a rational form is a typical scientific program. This is why the philosopher Ernst Cassirer (1925) saw astrology as a fundamentally scientific form of thought. She uses explanations "which, however uncertain and unfounded they may seem in detail, yet belong to the general type of causal thinking, causal inference and inference". Astrology is thus a description of the world on a par with modern natural science, based on a completely different “concept of the world”, and therefore a falsification of astrology is not possible, especially from an epistemological point of view.

In the early 1950s, Karl Popper made a distinction between science , pseudoscience and metaphysics within the framework of the critical rationalism he founded , which strongly shaped the philosophy of science until the 1970s / 1980s, in the ultra-modern era . According to Popper, the astrology case calls into question a common distinguishing feature: It is often argued that science is differentiated from pseudoscience or metaphysics by using an empirical method based on observation and experimentation . But this also applies to astrology, which collects a stupendous mass of empirical evidence based on observation and yet does not meet scientific standards. For Popper this was due to the fact that astrology (in his view similar to psychoanalysis ) works more like a " myth " that seeks confirmation of his convictions instead of testing hypotheses against reality with an open-ended result. Astrologers are impressed and misguided by what they consider to be confirmations of their assumptions. What's more, they formulated their interpretations and prophecies so vaguely that anything that could be considered a refutation could easily be argued away. This destroys the testability of the theory, which is therefore not falsifiable . So the derivation from archaic myths is not the essential problem of astrology - this applies to all scientific theories - but that it has not developed in the direction of a test capability. In this sense, astrology has been criticized in the past for the wrong reasons: followers of Aristotle and other rationalists , including Isaac Newton , have attacked above all the assumption of the planetary effect on terrestrial events. Both Newton's theory of gravity and the tidal theory are essentially based on astrological traditions of thought. While this circumstance caused great reluctance in Newton, Galileo Galilei would have completely rejected the - now generally accepted - tidal theory due to its historical roots. For Popper, astrology was thus a pseudoscience (pseudo-science), because although it proceeds inductively and empirically (and thus gives the appearance of being scientific), it systematically evades its examination and thus does not redeem its scientific appearance.

From the late 1960s onwards, Thomas S. Kuhn objected to Popper's argument that neither the forecasting methods nor the handling of false prognoses excluded astrology from the scientific canon. Astrologers have always reflected on the epistemological problems of their approach, pointed out the complexity and susceptibility of their methods to error, and discussed unexpected results. For him, astrology is not a science for another reason: astrology is essentially a practical craft , similar to engineering , meteorology or early medicine . There were rules and experience, but no overarching theory. The focus was on application, not research. Without theory-led problem solving, astrology could not have become a science, even if the assumption had been correct that the stars determine human fate. Even if astrologers made testable predictions and found that they did not always apply, they did not develop structures typical of science ( normal science ).

For Paul Feyerabend , the core problem of astrology in the 1970s was neither the lack of ability to test nor the lack of intention to solve problems, but rather its lack of further development. Astrology had very interesting and well-founded ideas, but not consistently continued and transferred them to new areas.

In 1978 the philosopher and scientific theorist Paul R. Thagard tried to synthesize the previous attempts at delimitation. He was looking for a complex criterion which, in addition to Popper's logical considerations, also included the social and historical aspects of Kuhn and Feyerabend. In contrast to Popper and in agreement with Kuhn and Feyerabend, Thagard referred to the “progressiveness” of a theory. By definition, a theory or discipline that claims to be scientific is pseudoscientific if it is less progressive than alternative theories over a longer period of time and at the same time contains numerous unsolved problems. Further characteristics are: The representatives of the theory make few attempts at further development, do not clear up specific contradictions, do not relate the assumptions of their theory to other theories and deal selectively with possible refutations. All of this is the case with astrology, which is why he calls it pseudoscience, and thus a general demarcation matrix can be developed using its example.

Today theorists of science and scientists almost always do not regard astrological teachings as science, but with different justifications and assignments. Astrological teachings represent a classic case study for the modern search of the scientific sphere for clear and comprehensive, but as few and as certain as possible differentiating criteria between science and non-science. The astronomer Joachim Herrmann defines it as a system of belief in the influence of the stars on people, which is not valid. The theologian Werner Thiede understands astrology “as a functionalization of astronomical-quantitative observations and calculations in favor of a cosmic and anthropological-qualitative interpretation of the stars”, which proceeds from “the all-interwoven nature of all things and a related analogy that also favors magical ideas ”. The classical philologist Wolfgang Hübner calls astrology "false doctrines" which, despite everything, would have outlasted the ages in their mixture of myth and rationality . Martin Mahner , a representative of the skeptic movement , classifies astrology in the pseudo- technologies because it is an applied discipline. Elsewhere, he calls it a non-science and shows its possible classification as parascience on or Para technology. The philosopher Massimo Pigliucci describes astrology as an “almost perfect example of pseudoscience” or “nonsense” (“ bunk ”), since its basic assumptions cannot be reconciled with the natural sciences and it has been proven that it does not work in practice. According to the Swedish philosopher Sven Ove Hansson, regardless of how one solves the demarcation problem between “real” science and non-science or pseudoscience, there is great agreement that astrology, like creationism , homeopathy , pre-astronautics , Holocaust denial and denial of the man-made global warming is a pseudoscience.

Some philosophers of science, however, regard the demarcation problem itself as a pseudo-problem. Accordingly, in some scientific or epistemological publications, astrology is called, for example, an art theory or non-science, but no longer a pseudo-science. In the encyclopedia Philosophy and Philosophy of Science, astrology is described as a “highly controversial art theory”. The astronomer Jürgen Hamel simply calls it a "doctrine" and affirms its non-scientific nature.

History of Western Astrology

Forerunner of astrology : It makes sense to differentiate between 'classical' astrology, which was mainly used in Hellenism and Ptolemaic Empire from the 3rd century BC onwards. BC originated, and preforms such. B. Astral cults for the sun , moon and Venus as well as other celestial bodies including their cult systems and objects, astral mythologies, cult calendars, astral divinations, etc. They were widespread prehistoric and ancient as well as ancient .

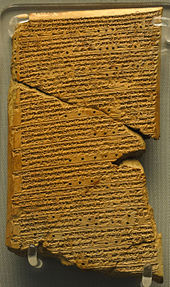

Mesopotamia, the influence of Egypt and antiquity

For Mesopotamia and especially Babylonia , three phases can be distinguished. The omen 'astrology' with a heyday between the 14th and 7th centuries BC. BC, the beginnings of a preform astrology with the still incomplete zodiac around the 6th century BC. And the first development of an astrological system from the 5th century BC. BC with the twelve signs of the zodiac, calculated planetary positions and omen-like interpretation of individual birth constellations.

Eastern Mediterranean : In ancient Egypt , arose towards the end of the 3rd millennium BC. As a pre-form of astrology with the dean stars or the 36 dean gods and rising and setting on the horizon, an extensive evaluation of favorable and unfavorable days. The 36 deans were probably combined in Ptolemaic Egypt with the Babylonian zodiac, which also encompasses 360 °. This presumably gave rise to the teaching of the "zodiac dean" rising at birth on the eastern horizon, and soon after that of the ascending zodiac degree, the horoscope ascendant .

Greek culture took over from around the 6th century BC. Elements of Babylonian astronomy. The Babylonian omen astrology and its elements were not taken over. After the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC Many Eastern mystery religions spread in the Hellenistic world, and astrological teachings were often associated with them. In the two centuries before and after the turn of the times , the system of classical or Hellenistic astrology emerged, especially in Egypt and Alexandria.

Elements of classical astrology : the twelve signs of the zodiac , the exact position of the planets with the sun and moon, planets raised in certain signs; Concept of 36 deans, with the ascending dean on the eastern horizon, from which the idea of the ascendant developed; the four elements , “male” and “female” signs, the sign rulership system (e.g. the moon “rules” over the sign Cancer ), planetary hours ; the twelve horoscope houses , planetary aspects , the “pars fortuna” or the “lucky point”, the annual solar horoscope, an hourly astrological method with the term “catarchs horoscopes” (choice of an astrologically favorable time).

In Rome , astrology gained great popularity in all classes of the population from the first century AD. The influence of astrology and of astrologers at the imperial court, however, subsided again in the course of the 2nd century. The notion that the movements of the planets completely determined the fate of humans was widely considered plausible at the time. Astrology found a philosophical justification mainly because of the Stoa with its fatalism . All ancient schools of philosophy took up astrology with the exception of Epicureanism .

Early Christianity found itself in a conflict with astrology because, according to many church teachers, the predestination of fate contradicts free will as an unconditional requirement ( conditio sine qua non ) of the Christian faith , on the other hand an astronomical event with an astrological statement regarding the birth of Christ was connected. After Christianity was elevated to the status of the state religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, astrology increasingly disappeared from both scholarly perception and the public. From then on, astrological views were reshaped in Christian terms and the occupation with astrology shifted to Persian, Mesopotamian and Muslim cultural areas. As a result of the weakening and dissolution of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, astrology largely dried up as a practiced and learned tradition in these territories. In the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium , astrology was retained, albeit weakened and also in the later, from the 7th / 8th centuries, from large fluctuations. In the 19th century, history traditionally attributed to the Middle Ages was shaped by Byzantium.

The complex or parts of the Hellenistic or classical astrology itself were probably already from the 2nd century AD. B. mediated on to India and included in the Greater Persian Sassanid Empire from the 3rd century . After the conquest of the Sassanid Empire in the 7th century, the new Muslim-Arab empire in turn received or translated the astrological ideas of Hellenistic, Persian and Indian origins found there.

Byzantine Empire

Byzantine Empire : The culture and spiritual life of the Byzantine Empire can be seen as the direct, Christian heir of late antique, Hellenistic astrology in the medieval Christian area, even before Latin-Christian Europe. With the astrological heyday in the neighboring Islamic-Arabian Orient, the astrology there, including the Hellenistic or classical astrology works received, was widely received in the competing Byzantine Empire. During Byzantine history, interest in astrology-astronomy, as well as its practice, varied considerably. Practice and teaching reached a high point during the Macedonian Renaissance in 9/10. Century. In the 11th and 12th centuries an upswing again took place during the Komnenen - dynasty instead.

For the Byzantine Palaiologoi can dynasty (13th-15th c.), Another golden age of astrology are detected, at which even the imperial court was involved in Constantinople Opel. In the late 14th century two scholars and astronomer-astrologers, Johannes Abramios and Eleutherios von Elis , were among a group of other students and astrologers, probably u. also working in Constantinople, tangible through various, sometimes more extensive, manuscripts.

middle Ages

In the medieval period of astrology between antiquity and late antiquity, with its classical, Hellenistic astrology, and the modern era , the question horoscopes and "elections" - choice of an astrologically favorable time for a project - from the field of so dominated in astrological practice and teaching mentioned hourly astrology as well as oral astrological topics . The interpretation of natal charts was rather rare or hardly possible in the High Middle Ages.

In the Middle Ages, astrology from late antiquity continued to be cultivated , especially in the Islamic cultural area , with the reception of Hellenistic astrology as well as Indian and Persian-Sassanid astrology elements. Arabic-Islamic astrology flourished in the Orient until the 11th century. Finally, with the conquest of Baghdad (1258) and the Arab-Islamic caliphate by the Mongols a. a. the broad teaching and practice of 'scientific' and court astrology often come to a standstill. However, especially during the Arab-Islamic rule on the Iberian Peninsula (8th – 15th centuries), called Al-Andalus , and the beginning of the Christian reconquest , some a. numerous astrology texts z. B. in Toledo through translations from the 12th century gradually received from southern Europe in high medieval Christian Europe, which led to the first European heyday of astrology from the 13th century.

Achievements of Arabic astrology : improved, more precise planetary tables - the ephemeris ; Further development of the so-called catarch astrology to the hour astrology still used today ; oral astrological consideration of history, especially with the so-called great conjunction ; Return horoscope or solar horoscope for the exact time of the return of the sun to the exact position of the birth sun; Use and interpretation of the so-called moon houses from Indian origin.

Latin-Christian Europe : Because astrological works were written almost exclusively in Greek up until late antiquity, actual astrology was unknown in the West until the High Middle Ages . Another reason for this was their condemnation by the Church. Simple, lay astrological forms from the complex of astrology, such as simple interpretations of the signs of the zodiac, especially as part of an adaptation to Christian teachings, shaped the initially few and mostly timid applications of astrological origin well into the High Middle Ages. Astrological prognoses and interpretations, applications such as methods based on a learned, scientific astrology in connection with the necessary mathematical-astronomical knowledge are only tangible from the 12th century in Latin-Christian Europe. This happened mainly as a result of the Arab-Islamic rule on the Iberian Peninsula (8th – 15th centuries) and the beginning Christian reconquest . In this context, u. a. numerous astrology texts z. B. in Toledo through translations from the 12th century gradually received in high medieval Christian Europe, with a first astrology bloom in the 13th century.

From the first half of the 13th century, the learned astrology in Latin Europe gradually spread from the south to the numerous larger cities that were emerging, in northern Italy perhaps even from Sicily, where Guido Bonatti is probably the best known and in many cases much later in Forli quoted astrologer / astronomer of the 13th century practiced. The Latin-European late Middle Ages with a growing population, increasing economic output and further founding of universities and urban high schools increased the demand and spread as well as independent further development of astronomy / astrology. As part of the Quadrivium of the Seven Liberal Arts , it had a permanent place in university education. When it came to astrology in today's (western) sense, it was usually called astrologia divinatoria (“prophesying astrology”), astrologia superstitiosa (“prophetic” or “superstitious astrology”) or astrologia in Latin, western Europe of the late Middle Ages and early modern times iudicaria ("judging astrology")

Astrology experienced another noticeable impetus in the transition from the late Middle Ages to the early modern period from Renaissance humanism . Typically, along with this development, the individual and a more antiquated pantheistic worldview moved more into focus, so that the creation and interpretation of natal charts increased significantly.

Renaissance and Copernican Turn

In Renaissance humanism and in the Renaissance , learned astrology experienced a further heyday, which lasted until the late 17th century. It was mainly cultivated at courts and universities, where it was linked to astronomy and medicine. The focus was initially in Italy. From Italy it then spread across Europe. But there was already resistance: the Italian philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) wrote twelve books Disputationes adversus astrologiam divinatricem , in which he sharply criticized the belief in fate of astrology (in its form as astrologia divinatoria ).

The invention of printing in the late 15th century greatly accelerated the spread and accumulation as well as the improvement of astrological works and textbooks such as ephemeris. Now the production of numerous popular astrological writings such as forecasts, annual forecasts, almanacs and representations of astrological medicine began. The development of Renaissance astrology was due to the fact that ancient writings that had been unknown in the Middle Ages were found again and that Arabic and medieval writings were distributed in printed form.

The so-called astronomical revolution , the development of the heliocentric worldview, first by Nicolaus Copernicus and then Johannes Kepler , presented astrology with new challenges. Some astrologers tried to adapt their system to the new teaching, but without success. Kepler himself, who, like Copernicus and Galileo Galilei , was convinced of the correctness of a properly understood astrology, emphasized that it could be easily reconciled with the heliocentric view of the world, since it is not the position of the heavenly bodies that matter, but their geometric relationship to one another as seen from earth. Copernicus and Kepler largely denied an Aristotelian-physical influence of the stars on human fate, understood astrology in a Platonic perspective with emphasis on a holistic cosmos and the correspondence of micro- and macrocosms, combined with a symbolic meaning of the stars. Because adjustments to the new worldview are not necessary, astrologers still use the terms from pre-Copernican times. The cultural scientist Angela Schenkluhn formulates that her “basic assumptions are based on the mathematical calculations of the geocentric worldview of antiquity”.

Rather, the problematic for astrology was the new paradigm that had prevailed since the publications of Copernicus, Kepler and, last but not least, Isaac Newton (who also believed in astrology) : Instead of a categorical separation of a sublunar and a supralunar sphere, the same natural laws now applied everywhere in the cosmos, instead of the assumption of a mysterious “sympathy” between inanimate objects, only that which was empirically measurable was now valid . Astrologers, who, like Kepler, did not want to limit themselves to the symbolic interpretation of star constellations, but instead stuck to the traditional worldview, exposed themselves to the ridiculous.

Decline

In addition to the Copernican turn, the massive instrumentalization of astrology for political, especially denominational purposes, the popularization of superstitious prophecies and the tightening of church control over the sciences in the course of the Counter-Reformation contributed to a gradual decline of astrology in the confessional age . After the Council of Trent , on December 4, 1563, an index commission banned all books that had to do with divination, magic , sorcery and deterministically oriented astrology. In the bull Constitutio coeli et terrae, Pope Sixtus V tightened the ban on astrology in 1586, although astrologers who defended the Aristotelian-Neo-Scholastic system against the Copernican were still accepted in Italy. With the breakthrough to the heliocentric worldview, astrology fell into disrepute in France as an old-fashioned and unscientific method and its study was strictly forbidden to members of the French Academy . On July 31, 1682, King Louis XIV banned astrological calendars and almanacs in France. When, towards the end of the 17th century, natural philosophy increasingly turned to a mechanistic view of the universe, the philosophical foundations of astrology lost their plausibility.

In the Age of Enlightenment, educated circles distanced themselves even more clearly from astrology, which evaded the criteria of scientific rationality. Although astrology was considered a superstition after 1750, and the Enlightenmentists regarded it as a "pseudo-science", Frederick the Great failed with his ban on the astrological house calendar because of the protest of the peasants. In 1736, Empress Maria Theresa forbade "all astrological fortune-telling and superstitious assumptions" in calendars and the reissue of ephemeris , thereby depriving the astrologers of the foundation. Astrology disappeared from the universities and from the public consciousness, the astrology historian S. Jim Tester speaks of a "second death of astrology".

Development of modern astrology

In the 19th century, especially in England, astrological studies flourished again, which were based on the Ptolemaic direction and mainly dealt with technical aspects and empirical tests. In France, however, astrology was not practiced again until the late 19th century, mainly in secret societies . At the same time, an esoteric variety of astrology developed in the English-speaking area around the Theosophical Society founded in 1875 , the most important representatives of which were Sepharial and Alan Leo . Leo's textbooks did a lot to popularize astrology. In Germany, Karl Brandler-Pracht in particular caused a resurgence of astrology from around 1905. In the following decades, various new approaches were developed there, including a. the half-sum astrology by Alfred Witte , which was made famous by Reinhold Ebertin's students .

In the 1920s, astrology titles with a strong psychological orientation in interpretation were published for the first time in German-speaking countries. The first tangible book of this direction came from Oscar AH Schmitz , which appeared in 1922 under the title The Spirit of Astrology and was already shaped by the analytical psychology of Carl Gustav Jung . Other representatives of this direction were Herbert Freiherr von Kloeckler and the doctor Olga von Ungern-Sternberg . In the English section was followed by a first turn to newer psychology by Dane Rudhyar with his book The Astrology of Personality (1936).

After the Second World War , astrology enjoyed increasing popularity again. It experienced a real heyday, as many people tried escapistically to escape from their perceived reality as oppressive. After the effects of the war waned, their spread decreased. In this respect, the sociologist of religion Günter Kehrer interprets it as a kind of "crisis symptom".

At present, astrology forms a large market that is largely covered by what is known as vulgar astrology: This includes commercial horoscopes in newspapers, on the telephone or on the computer, as well as several magazines and almanacs. Vulgar astrology is generally considered worthless. It refers exclusively to the sun signs and therefore cannot make any very specific predictions, since one twelfth of humanity is born in the same sign and can hardly expect the same fate on the same day. It is primarily used for entertainment . But there are also pure traders who, under the pretense of astrological knowledge, aim to pull the money out of their customers' pockets.

There are three important schools in serious astrology today: one that understands astrology as an esoteric occult science , a second empirically oriented, which is heavily statistical, and a third, which is oriented towards psychology . The latter is skeptical to negative about prognoses and places special emphasis on free will and human development opportunities. Most of the representatives of this direction refer to Jung's depth psychology , in which the principle of synchronicity plays an important role. Western astrology has been booming since the late 1960s. A major trigger was the concept of the Aquarian Age , as it became known through the musical Hair . Since then, astrology has gained new attractiveness as a way of life and self-discovery , whereby it increasingly focuses on the individual and dispenses with speculative prognoses . According to the religious scholar Karl Hoheisel , the widespread assumption of merely acausal relationships between the stars and human life does not fit well with the postulation of a new age in the philosophy of history , which implicitly implies causal effects. Since the fall of the Iron Curtain , it has also increasingly found supporters in the former Eastern Bloc , and in the course of globalization it spreads worldwide.

Astrology in other cultures

China

In the Empire of China , the emperor was revered as the son of heaven . At least since the 4th century BC Chinese cosmographers dealt with the cataloging of constellations and the recording of the celestial movements. In the princely courts of warlords , astrologers were constantly on the lookout for future events looming in the sky. During the 2nd Han dynasty (25–225 AD), different schools emerged according to which attempts were made to explain the worldview. One of the oldest interpretations referred to the sky as a movable canopy (t'ien kai) under which the earth rests motionless in the shape of a square, decapitated pyramid. Chinese astrology created a 28-part lunar calendar assigned to the imperial palaces as well as a twelve-part zodiac. In Chinese astrology, Jupiter rather than the sun plays a central role, which is why the well-known and popular throughout East Asia terms such as "year of the rat" and "year of the rabbit" come about by means of abstraction. Even before the birth of Christ, Chinese astrologers observed Halley's comet , from 28 BC onwards. Chr. Sunspots .

India

The Indian or Vedic astrology is Jyotisha called. It is based on certain writings from the corpus of the Vedas (2nd millennium BC). It was an integral part of higher learning and is still practiced today. Indian astrology includes many fixed stars in its interpretations and prefers the real constellations. The twelve signs of the zodiac , after which in today's western astrology were named in 30 ° large sky sections, are also used in Indian astrology and even have similar names (Mesha - Aries, Kartaka - Cancer etc.). Sometimes Indian astrology is also called "lunar astrology" because the position of the moon represents the actual "zodiac sign". The most important surviving works of Vedic and Indian astrology are the Brihat-Jataka by Varaha Mihira and the Hora Shastra by Parashara Muni. B.V. Raman, Ojhas and Shyamasunadara Dasa are particularly well-known in India as contemporary authors of important astrological treatises. B. V. Raman wrote over a dozen works in English, such as Graha Bhava Balas and Notable horoscopes . In contrast to today's western astrology, Indian astrology is based on the actually visible starry sky, in which the annual shift of the polar axis is taken into account (ayanamsa). Therefore, there is a difference of about 24 degrees between the position of the planets in Western and Indian astrology. There are many temples in India where the astrologers worship the nine main planets (Nava Graha) as deities. In addition to the creation of a natal chart, she also knows many other techniques of divination, such as Prashna, i.e. H. the calculation of the time of a specific question. The existence of so-called palm leaf libraries, of which there are a few dozen in India, but not all of which are recognized by leading astrologers, has attracted worldwide attention. It is here that the entire history of mankind was recorded on palm leaves a few millennia ago. However, some of these supposedly ancient documents have now been exposed as crude forgeries.

Maya

There are indications of astrological activities for Central America from pre-Columbian times , especially for the Mayan civilization . In addition to the sun and moon, great importance was attached to Venus. This was considered a messenger of bad luck and warbringer and was therefore watched very carefully. In particular, the appearance of Venus as the morning star was viewed as ominous; Several war deities were assigned to the morning star. The calamity heralded by Venus was attempted to be averted through ceremonies . The Maya zodiac consisted of thirteen signs.

The horoscope

In western astrology, statements and interpretations are often derived from a horoscope or a horoscope graphic, which shows the positions of the celestial bodies two-dimensionally in a simplified manner. These positions for a horoscope were already calculated mathematically in antiquity on the basis of tabular ephemeris , since the majority of the corresponding celestial bodies were and are not observable or visible at a certain point in time: because of daylight and clouds, at night and because the sky is only above Horizon is visible. Nowadays this can also be done with the help of computer programs. Traditional interpretation patterns play a role in the interpretation of the horoscope, but the astrologer is not bound by them.

Commonly used basic elements of the horoscope are, for example, the zodiac , the planets and their aspects as well as the so-called horoscope houses , the ascendant and various nodes such as the ascending lunar node and sensitive points such as the so-called lucky point. The zodiac is a division of the geocentrically considered orbit of the sun ( ecliptic ) over the fixed star sky into twelve equal sections. The twelve sections are the signs of the zodiac . The planets of astrology are the "wandering stars" of earlier geocentric astronomy, that is, those celestial bodies which, viewed from the earth, move visibly in relation to the fixed star sky. In addition to the planets of today's astronomy, these are also the sun and moon. The houses are also a division of the ecliptic into twelve sections, in this case according to the visibility at the relevant point in time.

calculation

The calculation of a horoscope normally means the creation of a horoscope drawing or figure for an event at a certain place on earth and a certain time. The drawing depicts the solar system from the point of view of the event location in a merely two-dimensional perspective . The location is taken into account according to geographical longitude and latitude , the event time at the location is converted into astronomical sidereal time . The basis is purely astronomical calculation methods. In the past, the ephemeris and so-called house tables (for calculating the horoscope houses) were used for the calculation; today, astrology software is mostly used that makes use of this. The event can be a birth, a coronation or founding of a state, a contract signature or a ship christening, also accidents of all kinds, laying of the foundation stone or annual horoscopes, etc. This is followed by the actual astrological activity, the interpretation.

Different types of horoscopes

Some geocentric horoscope forms at a glance:

- Birth horoscope ( natal chart): It should be the basis of interpretation for the description of the personality traits and the fate of a person, another living being or a state. The natal chart graphically shows the exact position of the star at a specific point in time. If one adds another, later created, one speaks of a transit horoscope, from which the astrologer can read off the astrological conflict or harmony situation at this point in time.

- Elections horoscope : It is created for any point in time in the future and is intended to help select favorable "constellations" for planned activities. In classical astrology well into the Middle Ages, this type of astrology was an important branch that was used as an oracle before significant political events and also for the time of a warlike act.

- Partnership horoscope (also relationship horoscope, synastry): This should provide information about the relationship between people and institutions (comparison of state horoscopes), including the relationship between business associates, colleagues, between a parent and a child or between siblings.

A distinction must be made between this and the form of publication known as the newspaper horoscope . The British R. H. Naylor is considered to be the inventor . On August 24, 1930, he published a detailed horoscope for the newborn Princess Margaret in the Sunday Express, and in the same post he predicted various events for the current week. Naylor published a follow-up post on August 31 of the same year with birthday-based astrological predictions for people born in September. A corresponding article for people whose birthday was in October followed on October 5th. From October 12, 1930, it became a weekly column. The column contained references to the signs of the zodiac from 1935 onwards. Later Naylor no longer divided his predictions into months, but according to the date range of the respective sign of the zodiac. This publication format for horoscopes was gradually adopted by numerous newspapers and magazines and is still very popular today.

Planets

Classical astrology takes into account the following seven heavenly bodies: the sun , moon , Mercury , Venus , Mars , Jupiter and Saturn . After the discovery of the unseen planets Uranus (1781) and Neptune (1846) and the dwarf planet Pluto (1930), these were subsequently integrated into the astrological worldview, and occasionally other dwarf planets and asteroids, for example (1) Ceres and (4) Vesta .

In the 17th century the astrologer William Lilly calls for the heavenly bodies a. a. the following qualities / properties:

- Moon: female, nocturnal planet; cold, damp, phlegmatic; well placed: calm, relaxed manner, delicate nature; fearful, peace-loving, inconsistent; tends to move and relocate; Lover of honest and witty science; badly off: vagabond, spiritless, unpredictable, satisfied with no condition of life;

- Mercury: neither male nor female; cold and dry, melancholy; well-off: people with a subtle, state-political brain, intellect and perception; very good opponent and logician; eloquent; learns almost everything without a teacher; tireless imagination, traders, seekers of mysteries; longs for travel and unfamiliar regions; badly off: laborious mind, confused man with tongue and pen against everyone; Liars, babblers, storytellers, gullible, donkeys without their own town point and opinion; without judgment, stealer;

- Venus: female planet, moderately cold and damp, stressed at night, the little happiness, originator of happiness and merriment, phlegmatic in blood and spirit in moods; well placed: calm person, pleasant, nice and clean; loves happiness in words and actions; musically; likes baths, happy meetings and stage plays; avoids work and toil; Shareholder; badly off: dissolute, wasteful, adulterer, without credit; Atheist and easygoing man, uses up his fortune in beer houses and taverns; lazy fellow;

- Mars: male, night planet, hot and dry, choleric, the little misfortune, originator of quarrels; well placed: unrelated in the art of warfare and courage, never submits, bold, steadfast, contentious, loves war, dares every danger, does not obey anyone; badly placed: gossipers without measure and honesty, murderers, instigators and rebels, traitors, careless, oppressors, violent;

- Sun: hot, dry, masculine, daytime planet, synonymous with happiness if in a good position; good position: trusting, keeps promises; urgent need to rule and rule everywhere; wise and great judgment; affable, very human to all people, generous, loves splendor and glory; badly off: arrogant, arrogant, disregards people, exhausting, foolish, wasteful, restless;

- Jupiter: planet of the day, male, moderately hot and humid, the great happiness, author of temperance, justice; well placed: generous, trusting, doing glorious things, honorable, religious, liberal, respectful of old people, lover of fair sharing, wise, powerful; badly placed: hypocritical religious, wasted inheritance, dogmatic, carefree, apostate, everyone cheats him; of gross receptivity;

- Saturn: planet of the day, cold, dry, earthy, masculine, greater misfortune, source of loneliness; well placed: profound imagination, serious in his actions, reserved in words, very economical in speaking and giving; patient at work, ambitious, weighty in discussions; badly placed: jealous, suspicious, addicted to profit, stubborn, hidden liar, never satisfied, vicious;

Peter Niehenke, on the other hand, leads in astrology. An introduction (2000) to the celestial bodies describes these basic astrological principles:

- Moon: maintaining life processes, need for human closeness and security, associative thinking, dreams;

- Mercury: central nervous system, information processing, language, sobriety, purposeful thinking, reason;

- Venus: homeostatic processes, female genital organs, lust-implausibility, sexuality, think more in aesthetic categories;

- Mars: muscles, blood, male sexual organs, aggression, risk taking, acumen, thinking in clear alternatives;

- Sun: driving force, life energy, heart, self-confidence, being in harmony with yourself, mentality (way of thinking, attitudes);

- Jupiter: growth, maturation, assimilation of nutrients, liver; Need to be good; Talent for happiness; Reason; Ability to intuitively recognize larger contexts;

- Saturn: defense, spleen, skin, pain, willingness to adapt, memory;

- Uranus: relationships with the nervous system, pituitary gland; Impulse to make changes; Intuition, brainstorm;

- Neptune: solar plexus, permeability and connectedness; Altruism, ancestors, invent;

- Pluto: regeneration, biological death; Urge to act destructive; Destruction of livelihoods; actively directed towards termination;

The astronomer and astronomy historian Jürgen Hamel, on the other hand, noted in Terms of Astrology (2010) a. a. the following astrological planet assignments:

- Moon: feminine power, symbol for rhythm, cyclical time, change, impermanence of the earthly, rules the times, feminine, damp and cold;

- Mercury: Leader, messenger, speaker, protector of trade, is in connection with science, little pronounced, planets which aspect it shape it; cold and damp; Inclination to rhetoric, geometry and philosophy;

- Venus: the little happiness, love, fertility, war, feminine, cold and damp, earthly joy, temporary well-being, song, music;

- Mars: the little misfortune, war, rebellious, unpredictable, exertion, manly, dry and hot, labor, enterprise;

- Sun: masculine, positive, warm and moderately dry, kind, symbol for rulers of all kinds, connection to gold, understanding and generosity, wealth, mild and honest, just;

- Jupiter: male, great happiness, moderately warm and humid, strive for higher values, generosity, aspects of social coexistence, peaceful, justice, reasonable and worldly, religious, happy; help people as soon as he can;

- Saturn: the great misfortune, cold and dry, male, justice, constancy, order, concentration on the essentials, reference to reality, discipline, demarcation (to others), master of time, spoiler and enemy of nature, embodied have to work, difficult, melancholy, rarely rich, unhappy, likes to stay alone,

- Uranus: striving for freedom and individuality, creative ideas and impulses, intuitive connection to universal consciousness, sudden change, departure into other dimensions;

- Neptune: feminine, slowly dissolving boundaries, longing, transcendence, spirituality, merging into greater things, inspiration;

- Pluto: mass movements, deep processes of change, crisis, healing, transformation, intensity, elemental force;

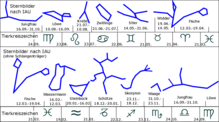

Zodiac signs

There are two different systems of signs of the zodiac that use the same measuring circle, the 360 ° zodiac with twelve signs of 30 ° each on the ecliptic . The positions of the astrologically considered celestial bodies and signs differ between the systems. The predominantly western-oriented method uses the tropical zodiac. The sections or individual signs of the zodiac have the same names as the names of the ancient constellations originally lying next to them .

- Sidereal zodiac

- The predominantly Indian-oriented method, known as Vedic Astrology , uses the constellations of the sidereal zodiac. As with the tropical zodiac, it divides the measuring circle into twelve sections of 30 ° and is still based on the ancient constellation Aries as the beginning of the zodiac, its ayanamsha value - a value listed in the ephemeris that indicates how many degrees of arc , minutes and seconds, the tropical from the sidereal zodiac - is officially oriented towards the opposition to Spica . Since the annually recurring positions of the constellations change very slowly due to the precession (by approx. 1 ° in 72 years), the point of the spring equinox moves around March 21 in the tropical zodiac apparently backwards along the zodiac constellations currently through the Constellation Pisces and according to the Vedic constellation classification will reach the constellation Aquarius in 2442 AD.

- Tropical zodiac

- The tropical zodiac is used extensively in western astrology. Its alignment at the four ecliptic points of the equinoxes and solstices of the sun gave the tropical zodiac its name, which is derived from the Greek τρόποι, trópoi , which means "turns, turning points". Based on the equinoxes and the solstices, the ecliptic is divided into twelve sections of 30 °, the twelve signs of the zodiac , starting from the spring equinox . So the tropical zodiac is a geometric abstraction because it does not correspond to the constellations on the ecliptic . In late antiquity, after the 5th century, it finally prevailed against the sidereal zodiac. Astronomers had already noticed several centuries before that the astronomical beginning of spring, which was then standardized on the sidereal zodiac or the ecliptic constellation Aries and on the "normal stars" previously known as this, was reached later in the year, and therefore migrated towards the meteorological summer due to the precession also shifted the ecliptic constellations in relation to the annual cycle.

Around 300 BC In Hellenism, the idea of giving a certain interpretation to the individual zodiacal sections developed. It was supported by the division of heaven into deans and their meanings, which had long been practiced in Egypt. Later, the dean interpretations developed from this within the natal chart. Due to the already known four-element-doctrine (water, air, fire, earth), which developed from the 6th to 5th century BC ( Thales of Miletus , Anaximenes , Heraklit , Empedocles ), in ancient ideas the expression of a fundamental tetrad, as well as the theory of harmony of the Pythagoreans , who formed geometric figures, triangles (trigons) and squares (tetraktys) with counting stones and large ones Attached importance (odd numbers: limited, male; even numbers: unlimited, female), together with the zodiac, a new combination and assignment was created.

But it was only with Aristotle 's (384–322 BC) then very successful, systematic explanations of physics and the cosmos that the established four-element theory was firmly incorporated into the complex of astronomical-astrological teachings. In addition, he expanded the four-element theory with the assignments of dryness or moisture and heat or cold. The resulting combination led to an order in which: dryness and warmth the fire; Moisture and warmth the air; Moisture and cold the water; Drought and cold the earth.

The four elements are u. a. in connection with the zodiacal qualities or modalities cardinal , fixed and movable or variable, assigned to the twelve signs, in which one element and one modality are linked to a zodiac sign. The lion, for example, is therefore a fire symbol with a fixed quality, characteristics such as stability and perseverance, steadfastness and strength, etc. are among the fixed qualities. The signs of the zodiac can also be divided according to the respective elements into the fire signs (Aries, Leo, Sagittarius) and earth signs (Taurus, Virgo, Capricorn), into air signs (Gemini, Libra, Aquarius) and watermarks (Cancer, Scorpio, Pisces). The twelve signs are also often differentiated according to the two genders, female and male , alternating in succession in the zodiac: The zodiac sign Cancer is considered female, the following Leo sign is male, the Virgo following the Leo sign is female, etc.

Ascendant

The ascendant depicts the ecliptic point rising on the horizon at a certain point in time, which rises at a certain point in time and place in the east of the place of the event; it falls to a certain degree of the zodiac sign on the east horizon at the same time. The ascendant is viewed as an independent, particularly important and individual point of action in the horoscope, which on the one hand depicts the beginning of the first house, all subsequent horoscope houses are dependent on the ascendant. On the other hand, it is assigned a special quality and function astrologically, which is often as significant as that of the sun in the horoscope. For example, one connects the ascendant with the personal disposition of the born, the basic need in life, character and temperament, appearance and physicality, the individuality of a person, in psychological astrology the ego par excellence, in connection with the zodiac sign or also the zodiac sign -Section in which the ascendant is.

Houses or fields

The exact point in time and the geographical location for which a geocentric horoscope is calculated determine the position of the “houses”, also called fields, which are calculated from the snapshot of the earth's rotation. The houses are the representation of the geocentric point of view of the zodiac from a geographical point . The degree of the ecliptic that just rises above the horizon is called the ascendant (ascendant) and marks the beginning of the first house. This is followed by three houses to the point of the lower culmination of the zodiac, i.e. the lowest point below the horizon, then three houses to the just setting point of the zodiac (Descendent, DC), three houses to the upper culmination, and finally three houses back to the Ascendant. Because of the angle of around 23 ° 26 'between the plane of the earth's orbit and the equator , the houses are generally of different sizes on the ecliptic.

The ascendant marks the top of the first house, from which the rest are counted, moving eastwards below the horizon. The houses follow one another as 1st to 12th house. The houses can be imagined as an orange peel cut into twelve equal pieces in the usual way, with the stem and remnants of the orange blossoms lying exactly at the north and south point of the horizon, a line of intersection running north to south along the sky and below the earth back to the north again, one along the horizon, with two more cuts in between on each side. However, the distance between the planets and the ecliptic is usually not taken into account when assigning houses.

Depending on the astrological school or direction, the houses are partly calculated according to different systems, which can lead to deviating or even contradicting statements. One house system is that according to Campanus von Novara , others according to Porphyrios and Regiomontanus , Placidus de Titis or Walter Koch . In the often used equivalent system , the houses are shown from the ascendant of the same size in 30 ° sections. With the other systems, the houses are of different sizes depending on the projection plane used (the cutting plane in the orange picture).

Just as the signs of the zodiac are interpreted as having different characteristics and the lights of the sky (planets, sun, moon) have different properties, so the houses represent different areas of life (I am, I have, I think, I feel, etc.) in which the zodiac signs and planets present there should make themselves felt accordingly. These areas of life are sequentially assigned to the houses in symbolic analogy to the properties of the signs of the zodiac, starting with Aries.

Aspects

The distance between two horoscope factors, such as the planets, is expressed in terms of angles . Special importance is attached to some angle sizes , these angles are called aspects (Latin aspiciere - to look at, to look at) and are often drawn in as connecting lines in horoscopes. Traditionally, well into the 20th century, these were the sextile and the square , the trine and the opposition, and the conjunction . In ancient times, as it was centuries later, the latter was not considered an aspect, and especially the conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn has been given a separate interpretation under the concept of the grand conjunction for the astrological view of history since late antiquity until well into modern times . As a special case, the so-called mirror points are often considered , which in the astrology history in turn are partly not counted as aspects and accordingly just as little interpreted. Meanwhile, a still increasing number of further aspects, depending on the astrological direction or school, are included in the interpretation. So z. B. the half square or quintile . The half-sum interpretations introduced by Alfred Witte take particular account of the symmetry properties of the aspects. According to astrological view, the effectiveness of the aspects is not limited to the exact angular distances, which are practically never given. Rather, a scattering area, the so-called orb, is allowed around it, which can be of different sizes depending on the astrological school. Newer views assume a continuous decrease in the effectiveness with the distance from the exact value.

reception

For a long time, criticism of astrology was mostly on an abstract and philosophical level. For example, the different fates of people who were born at the same time were discussed, or the lack of plausible explanations of how the postulated astrological influences should take place. Today's criticism of astrology, on the other hand, relies primarily on controlled empirical studies in which the - also psychologically justifiable - ability of astrologers to derive statements about the associated person from horoscopes, which, however, regularly did not result in a hit rate beyond chance .

Empirical studies

In 1979 Kelly found in a meta-analysis of the studies available to date that

- the vast majority of empirical studies carried out with the aim of verifying the astrological doctrine which could not confirm its claims and

- “ The few studies that are positive need additional clarification. "(, German:" the few supporting studies require further clarification. ")

Some scientific studies have come to the result that there is no ascertainable connection between interpretive elements of astrology and human characteristics such as intelligence or personality, as they are typically operationalized conceptually in psychology . Astrologers do no better at predicting future events than they do at random guessing. One of the most famous studies is Shawn Carlson's double blind test, published in 1985 in the journal Nature .

David Voas investigated the question of whether the success in the relationship and a feeling of attraction to the life partner correlate with the astrological statements that specifically state this. For this he had personal data of over eleven million people from Wales and England at his disposal. The study showed that marriages between partners who were “more suitable” from an astrological point of view would not last longer, nor that there was a higher distribution of partners who were more astrologically “compatible”.

A Danish-German research team led by Peter Hartmann evaluated the data of a total of more than 15,000 people statistically in a large-scale study : a connection between date of birth - and thus also the so-called "star sign" (the zodiac sign in which the sun is at the time of birth stands) - and individual personality traits could not be proven. “This cannot disprove astrology as a whole, but a direct connection between being born in a certain zodiac sign and personality is very unlikely to exist, the researchers conclude.” ()

In addition, various authors emphasize decisive methodological weaknesses in apparently supportive studies such as selective selection of test subjects, inaccuracies in the time of birth or insufficient number of test subjects. For the positive results of such studies, the researchers found alternative explanations, so people with astrological knowledge tend to behave according to their expectations about their respective zodiac sign.

Astrological twins , that is, people who were born at the same time, should be the best test of astrology's performance in the opinion of many astrologers and critics of astrology. In an extensive, scientifically conducted study, no correlations between date of birth and significantly higher similarities were found in astrological twins compared to other people.

In 1997, Gunter Sachs wanted to show in his book The Astrology Files by means of 300,000 examined cases that there were statistically significant correlations between the signs of the zodiac of the examined persons and everyday phenomena such as marriage, accident, illness, interests or suicide. a. to 25 statistically significant frequent and rare marriage combinations. He believed that he could also verify this by means of control experiments ( artificial zodiac signs by means of random selection). However, statisticians pointed out gross methodological errors in Sachs' book. A statement published in March 2011 by statisticians Katharina Schüller and Walter Krämer came to the conclusion that the technical and methodological errors that statisticians previously claimed in Gunter Sachs 'evaluations did not exist - which, however, did not prove the correctness of Sachs' Assertions may be misunderstood.

psychology

In addition to self- projection, there are other theories in psychology, such as external projection (similar to learning the gender role ) and the affirmation factor for vague statements (so-called Barnum effect ), which call into question self-confirmation via the horoscope. This affirmative tendency is given, for example, in personality descriptions that contrast opposites in a balanced relationship (“You are basically a sociable person, but sometimes you withdraw and don't want to talk to anyone”). There are well-founded studies for these effects that describe their sometimes strong effects. Similar to the physical criticism, only a barely measurable hint of an external influence remains for the astrological part. Rather, possible observations are the expression of what has been learned as a direct result of the shaping of the psyche by the astrological model. In this context, a study carried out in 1978 by the psychologists Mayo, White and Eysenck showed that, depending on their knowledge of celestial states, people who know this structure of thought and consider it to be important for themselves also reflect the positions of the planets . However, these abnormalities disappeared precisely when people were tested who were not aware of any astrological claims.

Only analytical psychology according to C. G. Jung is open to astrology and understands it as an expression of synchronicity . Jung had a particularly strong influence on so-called "psychological astrology". Jung's terms and their content descriptions such as “animus / anima” and the “shadow” , the persona and the “ individuation ”, the “doctrine of archetypes” and the “synchronicity” model are used in astrology, for example. B. often used in the interpretation of natal charts. In addition, Jung himself had extensive knowledge of astrology, so that, for example, when working with his clients he created natal charts for them and included the horoscope interpretation in his psychological work, as Jung had already written in 1911 in a letter to Sigmund Freud. Representatives of a Jungian astrology are z. B. the psychoanalyst and astrologer Liz Greene , the composer, painter and astrologer Dane Rudhyar and the psychologist, therapist and astrologer Peter Orban .

However, theories and models of analytical psychology are viewed more critically by academic psychology, since from the point of view of university psychology they are often obtained with unscientific methods.

Churches

The Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) advises its believers to use astrology as an instrument for predicting a supposedly fixed fate with care and aloof. The Central Office for Weltanschauung questions of the EKD sees a need for spiritual orientation in the modern world in the popularity of astrology and especially in its development as a method of life counseling. Thinking in symbols, as is the case with astrology, can certainly promote constructive self-knowledge in a good sense. At the same time, with the astrological interpretation, a stranger has enormous interpretative sovereignty over their own life, from which dependencies and other negative consequences could arise. From a Christian perspective, however, the stars are not rulers of life, but only God . The Christian faith is based on the fundamental freedom of a Christian to live his life under his own responsibility before God and to determine his own fate. This freedom and thus also the independent acting before God is endangered if one allows the stars or a star interpreter to have authority over one's own fate. Martin Luther replied to the astrological warning against crossing the Elbe in a boat on a certain day with the words “Domini sumus” (“We are of the Lord”) and jumped into the boat. This is an example of how to deal constructively with the topic as a Christian. The Protestant university pastor Andreas Fincke criticizes the fact that astrology often has religious or substitute religious traits and conveys the conviction that one is dependent on or shaped by impersonal, transcosmic powers instead of living a life of freedom and responsibility before God.

The Catholic Church rejects astrology and all forms of "fortune-telling". In their catechism , paragraph 2116, with reference to scriptures, rejects all "acts that are wrongly believed to 'unveil' the future" ". Such activities conceal the will to gain power over history and other people as well as "to incline other powers". This contradicts “the respect filled with loving awe” which one owes as a Catholic “God alone”.

natural Science

The science rejects all forms of astrology on the basis of their "undisputed unscientific". In 1975 the American magazine The Humanist published a statement entitled Objections to Astrology . At the beginning it said: “We, the undersigned - astronomers, astrophysicists and natural scientists from other disciplines - would like to warn the public against unchecked trust in the predictions and advice that astrologers make and give privately and publicly. Those who want to believe in astrology should keep in mind that there is no scientific basis for their teachings. ”The declaration was signed by 186 scientists, including 18 Nobel Prize winners. The following year the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP) was formed, in large part in response to the enormous popularity of astrology. Soon followed by similar organizations naturalistic positions representing scientific skepticism in other countries. These made it one of their main concerns to counteract the belief in astrology and other subjects that they understand incompatible with the natural sciences such as alien abductions , clairvoyance, homeopathy , etc. and to warn against their use.

population

According to surveys in some Western countries, around a quarter of the population is convinced that astrology can make accurate statements about personality traits or about events in a person's life. In 2009, around 25% of Americans believed in astrology, but mixed it with reincarnation and spiritual energy. In Germany, 23% believed that “stars influence our lives, but […] are not the only influencing factors”, and 2% that “our life path […] is only determined by the stars”.

In 2017, 38% of Viennese believed that “the description of their own zodiac sign is at least more applicable to their own character and behavior.” In Vorarlberg, 28% believed (very) strongly that “the position of stars or planets [i] your life” influence and 16% find horoscopes in newspapers, magazines or on the radio (very) important. The tendency to believe in astrology is explained at least in part by what people know about science, but also by personality traits. For example, 8% of Americans believe astrology is very scientific.

Legal situation in Germany

The right to do astrological activity is protected in Germany by the basic right to freedom of occupation . In 1965, the Federal Administrative Court with its judgment with reference to Art. 12 GG repealed bans that were in force in some federal states, for example the Bremen divination ordinance of October 6, 1934. However, since the profession of "astrologer" is not legally defined and is not subject to any state supervision, there are no restrictions on access to and exercise of the astrologer's profession. Only the obligation to notify according to § 14 of the trade regulations has to be observed.

Up until 2011, according to a judgment of the Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court, a "contract for setting horoscopes on astrological basis [...] is aimed at an objectively impossible performance that leads to nullity." In the course of judgment III ZR 87 / 10 In 2011 the Federal Court of Justice ruled that “fortune tellers […] are generally entitled to a fee”, “unless they exploit unstable people”. This was preceded by the lawsuit by a card reader on her fee for services rendered. The Federal Court of Justice then ruled that the promise of using supernatural, “magical” or parapsychological powers and abilities according to the state of the art in science and technology simply cannot be provided. However, someone “buys” services with the full awareness that their fundamentals and effects cannot be proven according to the knowledge of science and technology, but only correspond to an inner conviction, a belief or an irrational attitude that is incomprehensible to third parties Content and purpose of the contract as well as the motives and ideas of the parties contradict to deny the claim for remuneration.

literature

- Udo Becker: Lexicon of Astrology. Freiburg 1981.

- Nicholas Campion: A History of Western Astrology. 2 volumes. Continuum, London / New York 2008, 2009.

- Hans Jürgen Eysenck , David Nias: Astrology - Science or Superstition? List Verlag, 1987, ISBN 3-471-77417-3 .

- Jürgen Hamel : Terms of Astrology. From evening star to twin problem. Harri Deutsch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, ISBN 978-3-8171-1785-7 .

- James Herschel Holden: A History of Horoscopic Astrology. 2nd Edition. American Federation of Astrologers, Tempe (USA) 2006.

- Wolfgang Hübner : Natural Sciences V: Astrology. In: Der Neue Pauly , Vol. 15/1, JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2000.

- Ivan W. Kelly: Why Astrology Doesn't Work. In: Psychological Reports. 82 (1998), pp. 527-546.

- Gustav-Adolf Schoener: Astrology in the European history of religion. Continuity and discontinuity (= Tübingen contributions to religious studies. Volume 8). Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt 2016.

- Christoph Schubert-Weller: Ways of Astrology - Schools and Methods in Comparison. Chiron Verlag, Mössingen 2000, ISBN 3-925100-22-9 .

- Kocku von Stuckrad : The struggle for astrology. Jewish and Christian contributions to the ancient understanding of time. De Gruyter, Berlin 2000.

- Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50905-3 .

- Christl Oelmann: Power and powerlessness in the horoscope: Astrological interpretation - psychological help. Astrodata, Wettswil 2019, ISBN 978-3-906881-05-8 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Siegfried Wollgast: Philosophy in Germany between the Reformation and the Enlightenment, 1550–1650. De Gruyter, Berlin 2016, p. 249.

- ↑ Stephan Heilen (ed.): 'Hadriani genitura' - the astrological fragments of Antigonos of Nikaia. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2015, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: History of Astrology . Beck, Munich 2003, p. 266.

- ↑ Wolfgang Huebner: Astrology. In: Hubert Cancik , Helmuth Schneider (ed.): The new Pauly. Encyclopedia of Antiquity , Volume 2. Stuttgart 1997, p. 123 f.

- ↑ Angela Schenkluhn: Astrology. In: Metzler Lexikon Religion. Present - everyday life - media. JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2005, volume 1, p. 101; Jürgen Hamel: Terms of Astrology. Harri Deutsch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 389 f., Sv Makrokosmos and Makrokosmos-Mikrokosmos ; similar to Kocku von Stuckrad : History of Astrology. Beck, Munich 2003, p. 16.

- ^ A b Annelies van Gijsen: Astrology I: Introduction. In: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism. Leiden 2006, p. 109 f.

- ↑ Peter Niehenke: Critical Astrology . J. Kamphausen Verlag, Freiburg 1987, pp. 89-97.

- ↑ Jürgen Hamel: Concepts of Astrology . Verlag Harri Deutsch, Frankfurt am Main 2010, keyword Aristoteles , p. 125 f .; Keyword astrology , pp. 143–147, here p. 143.

- ↑ Mark Graubard: Astrology and Alchemy: Two Fossil Sciences. Philosophical Library, New York 1953 ( review, PDF ); similar to Lawrence E. Jerome: Astrology and Modern Science: A Critical Analysis. In: Leonardo, Vol. 6, 1973, pp. 121-130.

- ^ Lynn Thorndike: The True Place of Astrology in the History of Science. In: Isis , Vol. 46, No. 3, September 1955, pp. 273-278.

- ↑ Ernst Cassirer: Nature and Effect of the Symbol Concept. Darmstadt 1956, p. 24.

- ↑ Ernst Cassirer: On modern physics . 7th edition. Darmstadt 1994, p. especially p. 109 f .

- ^ Karl Popper: Science: Conjectures and Refutations. Lecture given in 1953, published under the title Philosophy of Science: a Personal Report in: C. A. Mace (Ed.): British Philosophy in Mid-Century, 1957 ( PDF ).

- ^ Johann August Schülein, Simon Reitze: Theory of Science for Beginners. 4th edition. Facultas Verlags- und Buchhandels AG, Vienna 2016, p. 234.

- ^ Popper: Conjecture and Refutation. P. 3.

- ^ Popper: Conjecture and Refutations. P. 16.

- ↑ “In the absence [of a more articulated theory], however, neither the astrologer nor the doctor could do research. Though they had rules to apply, they had no puzzles to solve and therefore no science to practice. " Thomas S. Kuhn: Logic of Discovery or Psychology of Research? In: I. Lakatos, A. Musgrave (Ed.): Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge. Cambridge University Press, London 1970 (23 pages; PDF ( Memento of May 12, 2013 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ “The remarks should not be interpreted as an attempt to defend astrology as it is practiced now by the great majority of astrologists. Modern astrology is in many respects similar to early mediaeval astronomy: it inherited interesting and profound ideas, but it distorted them, and replaced them by caricatures more adapted to the limited understanding of its practitioners. The caricatures are not used for research; there is no attempt to proceed into new domains and to enlarge our knowledge of extra-terrestrial influences; they simply serve as a reservoir of naive rules and phrases suited to impress the ignorant. " Paul Feyerabend: The Strange Case Of Astrology. In: Science in a Free Society. Verso, 1978, p. 96 ( PDF ).

- ^ Paul R. Thagard: Why Astrology is a Pseudoscience. PSA: Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association , Vol. 1978, Vol. 1, pp. 223-234 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Joachim Herrmann: Astrology . In: Irmgard Oepen et al. (Ed.): Lexicon of Parasciences . Vol. 3, series of publications of the Society for the Scientific Investigation of Parasciences (GWUP). Lit Verlag, Münster / Hamburg / London 1999, pp. 26–29.

- ↑ Werner Thiede: Astrology I. The history of religion . In: Religion Past and Present . Fourth, completely new revised edition, Vol. 1, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1998, Sp. 856.

- ^ Wolfgang Huebner: Natural Sciences V: Astrology . In: Der Neue Pauly , Vol. 15/1, JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2000, Col. 831 f.

- ↑ Martin Mahner, keyword parascience / pseudoscience / pseudotechnology, in: Irmgard Oepen u. a. (Ed.): Lexicon of Parasciences . Volume 3, series of publications by the Society for the Scientific Investigation of Parasciences (GWUP). Lit Verlag Münster Hamburg London 1999, pp. 228–230, here p. 230.

- ^ Martin Mahner : Demarcating Science from Non-Science . In: General Philosophy of Science . Elsevier, 2007, ISBN 978-0-444-51548-3 , pp. 516-575, 516; 560-564 , doi : 10.1016 / b978-044451548-3 / 50011-2 (English, elsevier.com [accessed March 30, 2019]).

- ↑ Massimo Pigliucci: Nonsense on Stilts. How to Tell Science from Bunk . University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2010, pp. 62-68, p. 62.

- ^ Sven Ove Hansson: Science and Pseudo-Science , Section 6. Unity in diversity . In: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2008/2017), accessed September 29, 2019.

- ↑ Steven French, Juha Saatsi (Ed.): The Bloomsbury Companion of Philosophy of Science . Bloomsbury Academic, London / New York 2011, p. 438 f., Keyword demarcation problem .

- ↑ Jürgen Mittelstraß (Ed.): Encyclopedia Philosophy and Philosophy of Science. Volume 1: A-B. Springer, Stuttgart / Weimar 2005, p. 267 f., S. v. Astrology .