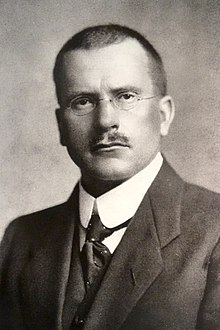

Carl Gustav Jung

Carl Gustav Jung (born July 26, 1875 in Kesswil , Switzerland ; † June 6, 1961 in Küsnacht / Canton Zurich ), usually CG Jung for short , was a Swiss psychiatrist and the founder of analytical psychology .

Life

Childhood and youth

Carl Gustav Jung was born as the second son of the Reformed pastor Johann Paul Achilles Jung (1842-1896) and his wife Emilie (1848-1923), daughter of the Basel Antistes Samuel Preiswerk , in Kesswil, Canton Thurgau . The grandfather of the same name, Karl Gustav Jung (1794–1864), originally came from Mainz ; he emigrated to Basel in 1822 and worked there as a professor of medicine until 1864. Carl Gustav was six months old when his father, a brother of the architect Ernst Georg Jung , moved to the rectory in Laufen near the Rhine Falls . Four years later, the family moved to Kleinhüningen near Basel, where his father took up a position as pastor in the village church of Kleinhüningen. When he was nine years old, his sister Johanna Gertrud ("Trudi") was born. After the death of his father on January 28, 1896, Jung had to look after his mother and sister as a young student.

Study and Studies

From 1895 Jung studied medicine at the University of Basel and also attended lectures in law and philosophy . During this time he joined the Swiss Zofinger Association . In his early student days he worked a. a. with spiritism , an area which, as his biographer Deirdre Bair wrote in 2005, was considered "related to psychiatry". His interest in this was awakened on the one hand by two inexplicable " poltergeist phenomena " in his first semester: he observed a table suddenly ripping and a bread knife cracking cleanly. From 1894 to 1899, Jung attended séances of his cousin Helly Preiswerk, who seemed to have media skills in a trance , and for two years, from 1895 to 1897, the weekly séances of a " circle of glasses and table backers", which focused on a fifteen year old " Medium ».

His colleague Marie-Louise von Franz commented on Jung's remarks on the psychological foundations of belief in spirits :

«This experience led him to regard all ghost appearances for a long time as autonomous, but in principle ' partial souls' belonging to personality ."

Jung specialized in psychiatry . He was already interested in this area due to the duties of his father Paul as pastor and consultant at the lunatic asylum in Basel (probably from 1886/87 to the end of his life on January 28, 1896). The decisive factor in Jung's decision was the reading of Krafft-Eving's textbook on psychiatry for general practitioners and students , in which psychoses are described as “illnesses of the person”, which for Jung “the two currents of my interest” as “common [s] field of the Experience of biological and spiritual facts ”combined.

In 1900, after completing his state examination, Jung worked as an assistant to Eugen Bleuler in the Burghölzli insane asylum in Zurich. During this time, from his observations of the phenomenon of the split personality , which he had gained on the basis of minutes of spiritualistic sessions, his dissertation on the psychology and pathology of so-called occult phenomena emerged in 1902 . In the winter of 1902/03 Jung assisted Pierre Janet at the Paris Hôpital de la Salpêtrière . His research at Burghölzli on brain tissue samples and his work with the then popular hypnosis to cure the symptoms of mental illness did not satisfy Jung's search for the origin and nature of mental illness. Only the continuation of the association studies developed by Wilhelm Wundt together with his colleague Franz Beda Riklin led Jung to an initial answer. The results of his association experiments, combined with the considerations of Pierre Janet in Paris and Théodore Flournoy in Geneva, led Jung to accept what he called “emotional complexes”. He saw in this the confirmation of Sigmund Freud's theory of repression , which was the only meaningful explanation for such autonomously behaving but difficult to access thought units.

Starting a family

In February 1903 Jung married the wealthy Schaffhausen girl Emma Rauschenbach (1882–1955); until 1914 she gave birth to four daughters and one son. She was interested in science, history and politics and was fascinated by the Grail legend . Her husband promoted her interests; for him she was not only an important interlocutor and critic of his texts, but also helped him in his work by taking over the writing. From 1930 she herself worked as an analyst. The wealth that she brought into the marriage was an important requirement for Jung's freedom of research.

Habilitation and opening of private practice

Jung completed his habilitation under Bleuler in 1905 with the results of his research on diagnostic association studies: Contributions to experimental psychopathology. In the same year he was promoted to senior physician at the Burghölzli psychiatric clinic and Bleuler's first deputy and was appointed associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Zurich. His lectures as a private lecturer were well attended. The habilitation thesis was published in 1906 and brought him first international recognition. In 1907, the year of his first meeting with Sigmund Freud , his work on the psychology of dementia praecox followed . Because of a falling out with Bleuler, Jung gave up his work at Burghölzli in 1909 and opened a private practice in his new house in Küsnacht on Lake Zurich.

Relationship with Freud

In 1900, at Bleuler's request, Jung gave a lecture on Freud's work On Dreams at an evening discussion among the medical profession . He had read “ as early as 1900 ... Freud's Interpretation of Dreams [published in 1899]. I put the book down again because I didn't understand it yet […] In 1903 I took the dream interpretation again and discovered the connection with my own ideas. “Subsequently, according to the editor of the correspondence with Freud, Jung referred to Freud's work in almost all published works up to 1905 (with the exception of his sexual theory).

In the last part of his habilitation thesis, Jung described the case of an obsessive compulsive disorder , which he first examined with association experiments and then successfully treated with Freud's method of psychoanalysis . He went into detail on Freud's 1905 work Fragment of a Hysteria Analysis . In the end, Jung remarked that the association experiment could be useful in relieving and accelerating Freud's psychoanalysis.

Jung's sending of the Diagnostic Association Studies to Freud in April 1906 and Freud's transmission of his collection of small writings on the theory of neuroses to Jung six months later marked the beginning of a close friendship and an almost seven-year lively correspondence and intensive exchange. Jung became a vehement supporter of Sigmund Freud's then unpopular views.

When they first met in Vienna in 1907, Freud and Jung spoke for thirteen hours, whereby both very similar interests and differences already became apparent: Freud had asked Jung “never to give up the theory of sex”. An early point of conflict was their different attitudes towards religion and the irrational : Jung took so-called parapsychological phenomena seriously, while Freud rejected them "as nonsense", even when, according to Jung, such a phenomenon (a repeated bang in the bookcase) occurred on the evening together should. Jung was disappointed with Freud's reaction and ascribed it to his "materialistic prejudice".

Freud appreciated that Jung, as a “Christian and the son of a pastor”, followed his theory. It was Jung's "appearance that [I] removed the danger of psychoanalysis from becoming a Jewish national affair", he wrote in a private letter in 1908. Freud saw Jung as the ancestor and continued leader of psychoanalysis and referred to him as the "Crown Prince".

When Jung stood up for Freud, who was unpopular at the time, he did so, as he wrote in 1934 and in his autobiography (1962), as an independent, autonomous and equal to Freud scientist, known for his association studies and complex theory. Jung later wrote that "his staff was subject to a fundamental objection to the theory of sex and lasted until the moment when Freud identified the theory of sex and the method in principle."

Jung was involved in Freud's movement and from 1908 worked as editor of the International Yearbook for Psychoanalytic and Psychopathological Research . From 1910 to 1914 he was President of the International Psychoanalytic Association .

But gradually the differences between the two became clearer. At the end of 1912, this led to the break after Jung had published his book Changes and Symbols of the Libido . In it he criticized Freud's concept of libido , "which proceeded from the primary importance of the sexual instinct that stems from the childhood of the respective individual," while he was of the opinion that "the definition must be expanded, the concept of libido must be expanded so that universal behavior patterns, too, which were common to many different cultures in different historical periods, would be captured by him ». Freud then declared that " he could not regard the work and statements of the Swiss as a legitimate continuation of psychoanalysis "

Following sharp personal reproaches from Jung, Freud terminated his friendship in writing in January 1913. In October of the same year Jung ended the professional cooperation and in April 1914 resigned the chairmanship of the International Psychoanalytical Association.

Relationship with Sabina Spielrein

Sabina Spielrein , who came from Russia , was a patient of Jung at Burghölzli from 1904 to approx. 1907, later Freud's pupil and colleague. Jung exchanged letters with Freud in 1906 and 1907 about the psychoanalytic treatment of Spielrein and in 1909 about "a wild scandal" with his now former patient.

Relationship with Toni Wolff

Antonia Wolff (1888–1953, called "Toni") worked for and with CG Jung from 1912, became his closest confidante from 1913 and his most important colleague and lover for many years from 1914 (some called Wolff Jung "second wife", see Jung -Biography of Deirdre Bair). Wolff is sometimes referred to as "Jung's analyst". Toni Wolff was his most important advisor during Jung's severe crisis after breaking with Freud. CG Jung remained married to Emma Jung, however, and they often appeared in threes. Toni Wolff co-founded the Psychological Club in Zurich in 1916, an association of followers of Jung's analytical psychology. She was president of the club from 1928 to 1945.

Isolation in the middle of life - traveling and coining terms Analytical psychology

After breaking with Freud, Jung gave up his teaching position as an associate professor at the University of Zurich in 1913. From then on he worked in his own practice, interrupted by extensive trips in the twenties: 1924/1925 to North America to the Pueblo Indians , 1925/26 to North Africa and to East Africa to the « native tribes » on Mount Elgon . In 1937 he traveled to India . Jung continued to publish his thoughts and views, which he now called analytical psychology .

As a result of the falling out with Freud, which, according to Jung, was due to his insistence on his sexual theory and Jung's adherence to his own interests in mythology and religious history, and thus ultimately to incompatible world views, Jung experienced a phase of internal disorientation and psychological pressure. That is why he began in 1913, in addition to his practice, to devote himself more to his unconscious, his dreams and fantasies, and recapitulated his childhood. He recorded dreams and fantasies as notes and sketches in "black books". These formed the basis of his “Red Book”, on which he worked until 1930.

Alchemy as "Proto-Psychology"

1928 Young learned through his friend sinologist Richard Wilhelm , the Taoist alchemy know and wrote in 1929 a psychological introduction to William's work on the subject. This encouraged Jung to study occidental alchemy as well. Jung discovered that his dreams and those of his patients contained parallel motifs to alchemy, and felt driven by his dreams to delve deeper into alchemical writings. 16 years later he published his thoughts on this in Psychology and Alchemy (1944) based on a natural scientist's dream series . Jung described the personal aspects of the individuation process mirrored in motifs of alchemy, as it also takes place in a deep analysis of the unconscious, based on an interpretation of the series of pictures from the Rosarium Philosophorum in The Psychology of Transmission (1946). In this respect Jung understood alchemy in 1954 as an early, unconscious description of "psychic structures" in the terminology of "material transformations", so to speak as a "proto-psychology", which is therefore significant for the psychologist, a "treasure trove of symbolism, knowledge of which for the understanding of neurotic and psychotic processes is extremely helpful ”. Conversely, the psychology of the unconscious is also "applicable to those areas of intellectual history where symbolism comes into question." He interpreted the alchemical figure of Mercury in Part 3 of his Symbolik des Geistes (1948) and wrote in two volumes in 1955 and 1956 about the "Coniunctio", the union of opposites in his late work Mysterium Coniunctionis. According to Isler, his exploration of alchemy can also be understood as a “struggle for the liberation of the“ new king ”from the depths of the collective unconscious”, that is, as an attempt to renew cultural awareness.

Jung and the (International) General Medical Society for Psychotherapy (AÄGP / IAÄGP)

Jung's increasing reputation led to his being invited in 1929 to give one of the main presentations at the annual congress of the supranational General Medical Society for Psychotherapy (AÄGP), which was founded in 1926, and was attended by participants from all over Europe . In the following year he was elected as vice chairman of the board of this association. After the " seizure of power " by the National Socialists, because of the resignation of the previous chairman Ernst Kretschmer, he became chairman and at the same time editor of the association's central journal for psychotherapy. Up until then, this had been organized, alongside Johannes Heinrich Schultz and Rudolf Allers, essentially by Kretschmer's friend Arthur Kronfeld as editor, who, as a German of Jewish descent, had to immediately stop any public activity. Jung promised to take over the office of President in 1933, "after long months of negotiations", provided the company was renamed and legally reorganized, especially the possibility of individual membership for Jews.

With the confirmation of the new statutes at the Nauheim Congress (Germany / Hesse) in May 1934, a neutral international organization with regional groups acting independently of one another, whose political and religious neutrality was bindingly enshrined in the statutes: the International General Medical Society for Psychotherapy (IAÄGP). The company headquarters were relocated from Berlin to Zurich. Jung was the editor of the Zentralblatt , but everyone else who worked for the company was still in Berlin.

From the beginning of his presidency, CG Jung personally took care of the legal structure of the new statutes of this internationally organized, politically neutral society that is independent of Germany. In order to enable membership and practice for Jews who had been excluded from the German national group, he had a Jewish lawyer friend in Zurich, Vladimir Rosenbaum, edit the future statutes of the society in such a way that Jewish colleagues can now also be independent of one Landesgruppe “individual members” could be. In order to limit the influence of the German national group, which has a superior number of members, Jung also ensured that each national group was not allowed to have more than 40% of the votes present. In addition, each national group should publish its communications in its own country-specific special issues. Jung wanted to keep the Zentralblatt as the scientific organ of the IAÄGP independent and politically neutral (i.e. out of the Nazi sphere of influence). So it was possible that at the same time the German national group was synchronized and the other members of the IAÄGP - at least until 1939 - could act independently.

As president from June 21, 1933 until his resignation in 1939, Jung contributed to maintaining the work of the AÄGP as the International AÄGP (IAÄGP). With his leadership role in the IAÄGP, Jung intended to save the still young psychotherapy in Germany beyond the time of National Socialism . Like many active members of the IAÄGP who urgently asked him for his presidency, Jung was of the opinion that as a politically neutral Swiss he could withstand the pressure of the National Socialists and enable society to be as independent as possible.

His presidency of the IAÄGP was widely criticized and brought him under suspicion of ingratiation to the National Socialists. As a motivation for his behavior, Jung referred to his sense of responsibility: taking over the presidency had thrown him into a “moral conflict”, but he saw it as his duty “to stand up for my friends with the weight of my name and my independent position. »

“In the event of war, the doctor who lends his aid to the wounded on the opposing side will not be seen as a traitor. He went on to say (ibid.), "(M) Support for German doctors has nothing to do with a political statement."

But the distinction between international freiheitlichem claim and the ambitions of conformist German Group failed to complete: The publication of the various numbers of the central sheet should switch between the National Groups and the first issue of Zentralblatt international society was in the hands of the German Group. Despite the required political neutrality and against Jung's express instructions - as he wrote in his reply to Bally's allegations quoted above in March 1934 - it contained a National Socialist declaration of principles by the chairman of the German regional group, Matthias Heinrich Göring , a cousin of the Reich Minister at the time Hermann Göring , reprinted without Jung having been informed beforehand by the editor ( Walter Cimbal , Hamburg), who on the other hand had supported Jung's efforts to help Jewish colleagues in 1933 and 1934. Instead of just the German ones, all regional groups received this politically oriented manifesto. It never became clear whether this was due to a mistake or deliberately by the secretary of the German national group. This declaration was also printed directly after Jung's editorial in the Zentralblatt with his reasons, intended for everyone except the German regional group, as to why he had assumed his office as President, which, contrary to Jung's intention, also appeared in the edition for the German regional group. This juxtaposition of Jung's editorial and MH Göring's declaration of loyalty to the Nazis gave the false impression that Jung agreed with the anti-Semitic policies of the Nazis, which he publicly opposed in the aforementioned reply to G. Bally's allegations in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung in March 1934 .

In her chapter Arg with contemporary history, Bair described in detail, based on the correspondence between Matthias Göring and Walter Cimbal, the efforts of the head of the German section, Matthias Göring, to benefit from Jung's reputation and to instrumentalize him for National Socialism. In view of this, in 1933 Cimbal expressed concern that “Jung would remain on the party line ”. Jung, on the other hand, tried - as his biographer Deirdre Bair wrote in 2005 - to strengthen the independence of his position, to counteract the scientific isolation of German psychoanalysts and to protect the Zentralblatt and the other regional groups from the influence of the Nazis. In 1934, for example, he appointed his Zurich colleague CA Meier as managing director of the international society and as secretary for the Zentralblatt , who was also supposed to watch over the political neutrality of the Zentralblatt and who regulated a large part of the IAÄGP's correspondence for Jung. Jung privately had Rudolf Allers, a Jew, write the reviews in the Zentralblatt and "used these reviews to keep German readers informed about research carried out in other countries."

As a result of the accusations related to his presidency and the content of the Zentralblatt , but also of power struggles and harassment on the part of the German section leadership, which had been brought into line, Jung submitted his resignation for the first time in 1935, but was persuaded by Matthias H. Göring to continue . In 1937 he threatened to resign again and in 1939/40, due to delays by M. H. Göring and complicated administration and formal problems, it took Jung a year to resign from office at the Zurich delegates' meeting on 5/6. August 1939 - after a further letter of resignation from Jung in July 1940 - became effective and was also accepted by Göring.

During this transition period at the beginning of the Second World War from July 1939 to September 1940, Jung acted as "honorary president" and CA Meier as interim manager until a new president was elected. The inclusion of the pro-National Socialist new national groups from Italy , Japan and Hungary , with which the German national group was able to achieve a majority of votes in the IAÄGP, were promoted by Göring and his group and attributed to Jung, which in turn gave the impression of a Nazi friendliness reinforced. Following the Vienna delegates' meeting on September 7, 1940, the German Institute for Psychotherapy , which was also headed by Matthias Göring, took over the management of the International Society.

In 1939 Jung's works were put on the "black list" in the German Reich , and in 1940 after the German invasion, on the French " Otto list " of prohibited works.

Jung's statements in the context of National Socialism

C. G. Jung commented, u. a. on German radio and in several essays, in a way that - taken out of context - can be interpreted as sympathetic to aspects of National Socialism and provided a basis for violent accusations against Jung. Jung's view of the "personal equation" was based on these statements about "Germanic spirit" and "Jewish psychology"; H. the different psychological requirements of individuals and groups that he determined and that he wanted to be understood in a value-neutral manner. He publicly referred to this in his editorial in the Zentralblatt 1933, in his reply of 13/14. March 1934 in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung on the previously published allegations of the psychoanalyst Gustav Bally , as well as privately:

In 1933 he wrote in the Zentralblatt:

“The differences between Germanic and Jewish psychology, which have long been known to those who understand and understand, should no longer be blurred, which can only be beneficial to science. In psychology, before all other sciences, there is a personal equation , the non-observance of which falsifies the results of practice and theory. As I would like to expressly state, this should not mean an underestimation of Semitic psychology. "

Jung wrote to his friend, the Jewish analyst James Kirsch, who questioned him in 1934 about his statements about Jewish psychology and the public outrage it triggered: the public misunderstand him, he was neither anti-Semite nor National Socialist.

The subject of psychological peculiarities of groups and individuals had already formed a subject of interest and research for Jung years before. In 1918 he wrote a warning about the "Germanic barbarians" whose soul, in addition to a civilized side, hides a "blonde beast" split off from it, who "turn around in their underground prison and threaten us with an outbreak with devastating consequences." B. could appear as a "social phenomenon". This research was also reflected in his 1921 "Psychology of Types". There Jung presented his findings and theories of how the typology of individuals influences their ideas, philosophies and preferences for action. Accordingly, a community or culture is also shaped by the typical structures of consciousness that predominate in it.

In addition, Jung saw it as his medical duty to respond to core problems he saw in this way, v. a. to draw attention to the powerful work of what he called the autonomous psychological factor "archetype of Wotan" and the complex of the "Jewish problem" in the hope that their conscious understanding of individuals could provide an understanding of the "collapsing contents of the unconscious at that time " enable. In this way, the consciousness can absorb and integrate this content. In this way, the social and political situation could be healed. The contents of the unconscious are namely “ not inherently destructive, but rather ambivalent, and it depends entirely on the nature of the consciousness that captures them, whether they turn out to be a curse or a blessing. " He explained:

"I admit that I am careless, so careless that I am doing the most obvious thing that can be done at the present moment: I put the Jewish question on the table in the house. I did this on purpose 'because' the first principle of psychotherapy is to speak in the most elaborate fashion of all those things which are the ticklest, most dangerous and most misleading. The Jewish problem is a complex [note: terminology of psychotherapy] [...], and no responsible doctor could bring himself to practice medical cover-up methods on it. "

According to his colleague Marie-Louise von Franz, Jung's “mistake” during this period was “therapeutic optimism, that is, his passion for medicine. Wherever the dark and destructive broke out individually or collectively, he tried with the passion of the doctor to save what could be saved ». For, as he said in connection with a malignant patient: "How could I practice therapy if I didn't keep hoping?" In a letter dated April 20, 1946 to Eugene H. Henley (New York), Jung wrote that "before the Hitler era, he still had illusions [about people]". "The monstrous behavior of the Germans" had them "thoroughly destroyed". He “never thought that a person could be so absolutely evil [...], in Germany evil [...] was unimaginably worse than usual evil.”

Regardless of his express intention, Jung's statements on Germanic-Jewish differences and his psychology were praised by National Socialist propaganda as "building up the doctrine of the soul", while at the same time Freud's writings fell victim to book burning. Despite his break with Freud, whose psychology and "corrosive [because in Jung's eyes reductionist] thinking" he criticized elsewhere, CG Jung praised Freud's achievements in 1934 in a lecture at the conference of the International Association of Psychotherapists in Bad Nauheim (Hesse) on complex theory . He honored Freud - at that time a target of Nazi hatred - as the "discoverer of the psychological unconscious" and Freud's "theory of repression" as the "first medical theory of the unconscious". As a result, Jung incurred sharp attacks on the following day in the German press, which "recorded exactly how often he uttered Freud's hated name."

Assessment of Hitler and National Socialism

In an interview with his former student Adolf Weizsäcker , broadcast on June 26, 1933 by Radio Berlin, which had meanwhile become nationalist in line , CG Jung made statements in which, according to Jörg Rasche (2012), he “apparently accepted the National Socialists' diction without any criticism” Suggested interview partner with questions. Jung said in relation to Hitler: “ As Hitler recently said, the Fiihrer must be able to be lonely and have the courage to go alone. But if he doesn't know himself, how does he want to lead others? »In the interview, however, Jung also warned against mass movements that« overpower the individual through suggestion and render them unconscious »and emphasized the need to increase« self-awareness and self-reflection »as well as« self-development of the individual »as« highest Goal of all psychoanalytic endeavors ”and spoke of how“ barbaric invasions […] took place internally in the psyche of the [German] people ”. According to Regine Lockot (1985), his answers could be taken by National Socialists as well as by opponents of the regime as confirmation of their worldview.

After this interview, Jung held a seminar in Berlin. Meanwhile, in a private conversation with his colleague Barbara Hannah, Jung expressed the fear, as she reports in her Jung biography (1982), “that ruin would be unstoppable. He could only be stopped if enough individuals were to become aware of the state of possession in which they were all. That is why it is our job to give them strength to doubt for as long as possible and to help as many as possible to become more aware. "

Jung laid out his deep psychological understanding of current events in National Socialist Germany in his essay "Wotan" (1936): The Germanic image of God of the wanderer and storm god Wotan had come to life again, which was "a step backwards and backwards". In addition to economic, political and psychological explanations, this is probably the strongest explanation for the phenomenon of National Socialism. Wotan had already shown himself in Nietzsche's writings (19th century), as well as - before 1933 - in the German youth and migrant movements . But now it is leading to the "marching" and "raging" of the entire population. Jung understands Wotan to be a personification of mental powers. The "parallel between Wotan redivivus [" resurrected "] and the socio-political and psychological storm that is shaking contemporary Germany [could] at least be regarded as an as it were." One could also describe the powerfully effective "autonomous psychological factor" psychologically as "furor teutonicus". "The storm broke out in Germany while we [in Switzerland] still believe in the weather." And: “Germany is a land of intellectual disaster”. "The earliest intuition has always personified these psychic powers as gods." Hitler was moved by it. "But that is precisely what is impressive about the German phenomenon, that someone who is obviously moved, grips the whole people in such a way that everything sets in motion, gets rolling and inevitably slips into dangerous slips." Jung quoted various properties ascribed to the god Wotan from Martin Ninck's Wotan monograph and concluded that Wotan embodied “the instinctual-emotional as well as the intuitive-inspiring side of the unconscious [...] on the one hand as the god of anger and frenzy, on the other hand as a rune and herald of fate. » He therefore expressed the hope that Wotan would also have to "express himself in his ecstatic and mantic nature" and that "National Socialism would not be the last word by a long way".

In January 1939, the New York International Cosmopolitan published the so-called Knickerbocker interview given by Jung under the title Diagnosis of the Dictators, in which Jung tried to explain Hitler and Nazism to the Germans from a psychological perspective. This interview was and is taken by critics as an excuse or legitimation. In it, Jung described Hitler as "seized" and "possessed", that is, Hitler was overwhelmed by the contents of the "collective unconscious". Hitler is someone who is under the command of a "higher power, a power within himself," which he obsessively obeys. "He is the people", d. H. For the Germans, Hitler represented that which lived in the “unconscious of the German people” (which is why other nations could not understand the fascination of the Germans with Hitler). In this sense, Hitler draws his power through his people and is "helpless ... without his German people" because he embodies the unconscious of Nazi Germany, what gives Hitler his power.

In this psychological function, Hitler would best correspond to the "medicine man", "high priest", "seer" and "leader" of a primitive society. This is powerful because one suspects that it possesses magic . Hitler actually works "magically", i. H. via the unconscious. He is "the loudspeaker that amplifies the inaudible murmur of the German soul until it can be heard by the unconscious ear of the Germans", i. H. For the Germans he played the role of a mediator to the expressions of their unconscious. According to Jung, what was activated there was the earlier “Wotan” image of God, but in a destructive way. Jung also stated that the Germans had an “inferiority complex” which was a necessary prerequisite for the “messianization” of Hitler.

His biographer Deirdre Bair emphasized in 2005 that Jung's statements from the “ Knickerbocker Interview ” and the fact that the contents of his Terry Lectures , which he held at Yale University in 1937 and published in English as Psychology and Religion in 1938 , led to this in 1939 that Jung's works in Germany and in 1940 after the invasion of France were also banned there and partially destroyed. In May 1940, through a warning of an expected attack on Switzerland, Jung learned that he was also on the National Socialists' “black list”.

After 1945 Jung was sharply criticized for his attitude in the early years of National Socialism. In 1945 the "Neue Schweizer Rundschau" published his essay "After the catastrophe", which can be understood as an indirect examination of his personal involvement. In addition, he never commented publicly on the allegations. Using archive material, Bair shows that Jung has been exposed to many attacks since his presidency in the IAÄGP from 1933 and that he told friends that his statements at the time had repeatedly been misunderstood. Since he also found the allegations of being an anti-Semite and Nazi from 1945 to be completely absurd and unfounded and some of them were twisted representations of his statements or direct slander, he expected a justification to make the attacks worse and to oppose one public justification decided. In his private life, however, as Gershom Scholem wrote to Aniela Jaffé in 1963, he is said to have said: "I slipped" - namely on the slippery floor of politics, as Marie-Luise von Franz added in 1972. Jung later said that he was too optimistic about the possibilities of a positive development and should have kept silent more.

In 1942 and 1943 Jung, via Allen Welsh Dulles, served the US secret service as a kind of " profiler ": Jung was supposed to analyze the psychological state of the leading National Socialists and the German people, to forecast their actions and possible reactions.

Jung's remarks about and relationship to Jews and Judaism

According to the sources, Jung's work was not shaped by any specific anti-Semitism , but his words about Jews appear politically naive, insensitive or opportunistic in part.

Rasche (2007) points out that Jung "like many of his contemporaries made careless, derogatory statements about Jews" and used the Nazi jargon of the time without reflecting on them, which is an objective assessment of the extent to which Jung's statements can be viewed as anti-Semitic. complicate. His statements had “ to do with the murderous anti-Semitism of Hitler and the Nazis only to the extent that they used such [already existing] figures of thought and idioms for their racist crimes. »

The close colleague Marie-Louise von Franz, who also knew him well in private, wrote that she had never heard anti-Semitic or National Socialist remarks from Jung. Jewish analysts such as Hilde and James Kirsch, who had emigrated abroad, said the same about their work with CG Jung and confirmed many other Jews who Jung made acquaintance with.

A careful reading of Jung's statements that sounded anti-Semitic in their context before and after 1933, which are often cited as evidence of possible anti-Semitism, shows that he endeavored to differentiate between the psychological conditions of Jews and Teutons and their respective strengths and weaknesses . In 1918 Jung wrote «About the Unconscious» about the fact that the period in which mankind has acquired a highly developed culture as «civilized man» corresponds to a thin patina in the soul «in relation to the mightily developed primitive (note: ie archaic) layers of the soul. These layers, however, form the collective unconscious, together with the relics of animality (note: the instincts), which point back into infinite, misty depths. " In this context, Jung characterized the soul of the "Germanic barbarians" (i.e. uncivilized) with a reference to the potential for destruction and that of "the Jews" in 1918 as follows:

“Christianity divided the Germanic barbarian into its lower and upper halves, and so it succeeded - namely by suppressing the dark side - to domesticate the light side and make it suitable for culture. The lower half, however, awaits the redemption of a second domestication. Until then it remains associated with the remnants of the past, with the collective unconscious, which must mean a peculiar and increasing animation of the collective unconscious. The more the unconditional authority of the Christian worldview is lost, the more audibly the 'blonde beast' will turn around in its underground prison and threaten us with an outbreak with devastating consequences. This phenomenon takes place as a psychological revolution in the individual, just as it can occur as a social phenomenon.

In my opinion, this problem does not exist for the Jew. He already had the ancient culture and has also acquired the culture of his host people. He has two cultures, as paradoxical as that may sound. He is domesticated to a greater extent, but in grave embarrassment about that something in man that touches the earth, that receives new strength from below, about that earthy thing that the Germanic man conceals in dangerous concentration. "

Jung's essay "On the present situation of psychotherapy" (1934) contains appreciative statements about Jews who are "much more aware of human weaknesses and downsides due to their twice as old culture [...] than non-Jews and those." "As a member of a 3,000-year-old cultural race" as well as "the educated Chinese psychologically conscious in a wider area" are considered non-Jews. Jung, on the other hand, saw the "Germanic barbarians" as only partially civilized. Their soul is therefore under great tension and has a high potential for destruction as well as it contains creative seeds for new things, from which a culture (first) still has to develop because it is necessary. The Jews already have a highly developed culture and therefore lack this tension.

Jung connects this idea with the situation of the Jews without a land of their own at the time, who therefore needed a "civilized host people to develop". In his subsequent assertion that “the Jew as a relative nomad has never and will probably never create his own culture”, Jung's one-sided picture of Judaism becomes clear. Jung's inductive fallacy results from this mixture of observation and prejudice that the Jew cannot create a culture either, "since all of his instincts and talents require a more or less civilized host people to develop".

With these comparisons Jung substantiated his distinction between "Jewish" and "Germanic / Aryan" "soul", the consideration of which is of decisive importance for psychotherapy, and delimited his view of the importance of the "personal equation" from that of Freud or Adler. Because of the differences that exist, according to Jung, the categories of the psychology of Adler or Freud are "not even binding for all Jews" and cannot be used "without looking at the Christian Germans or Slavs".

Jung's one-sided image of Judaism and Jewish culture was shaped by the "soulless materialism" and the reductionist view of Freud and other Jewish contemporaries, who themselves were completely ignorant of their cultural roots (e.g. Jewish mysticism of Kabbalah, wisdom teachings of Hasidism) . Jaffé explains that a general interest in Judaism did not set in until the Hitler era and that it intensified with the establishment of the State of Israel, to which works by Martin Buber, Gershom Scholem and Franz Rosenzweig contributed. Two statements by Sigmund Freud in letters to Karl Abraham show that these one-sidednesses and prejudices about Jews as well as the distinction between a “Jewish psychology” were also common among Jews. In May 1908 he wrote to Karl Abraham, "[...] you are closer to me in intellectual constitution through racial kinship, while he [young] as a Christian and the son of a pastor only finds his way to me against great internal resistance" On July 20, 1908, Freud wrote to Abraham to justify Jung's hesitation and reservations of psychoanalysis: "We Jews have an easier time on the whole [than Jung], since we lack the mystical element."

For a revision and profound expansion of Jung's knowledge about and more respect for Judaism, Jewish analysts such as B. James Kirsch (in letters between May 7, 1934 and September 29, 1934), and especially Jung's experiences after the war, which had "overturned his attitude to the Jewish psyche". From 1944 Jung worked intensively on Judaism, which in 1955 he regarded as the common root of his psychology and that of Freud and as the forerunner of alchemy, which he valued.

The Jewish lawyer Wladimir Rosenbaum found Jung's behavior in the 1930s, which appeared contradictory in some cases, and which exposed him to severe attacks, as evidence of Jung's sincerity. He wrote CG Jung on May 15, 1934, after Rosenbaum had rewritten the Society's statutes for Jung at his request, the following: He too had initially suspected that Jung was an anti-Semite. But

«The mishap that recently happened to you in the outside world [probably an allusion to the conflicts that brought him his presidency and the above-mentioned editorial in the Zentralblatt in 1934] taught me otherwise. Because if you were an anti-Semite you would not have maneuvered yourself into such a critical situation! "

Jung probably spoke to some analysands about his discomfort and conflicts regarding his presidency of the IAÄGP. An analysand Jung, who was an ardent sympathizer of the Nazis, wrote in May 1933, uncomprehending, “ he could not fathom […] why Jung was so reluctant to serve such a“ glorious social movement ”as“ National Socialism ” to be »()

Many of Jung's important employees and supporters were Jews, such as Erich Neumann and Jolande Jacobi . Jung supported Jewish refugees who did an analysis with him by giving free analysis lessons and by helping many of his Jewish analysands and colleagues through letters of recommendation to re-establish themselves professionally in emigration.

In his private life, Jung apologized to his Jewish colleagues and friends after the Second World War because of what he said in the early 1930s. He saw that he had injured her through political naivete and that his writings contained false statements [about Jews]. a. to a statement by Leo Baeck, passed on by letter, that Jung had told him that he had slipped (namely on the smooth parquet of politics, as added by Franz). Gershom Scholem reported this statement to Aniela Jaffé on May 7, 1963:

«Dear Ms. Jaffé, […] In the height of summer 1947 Leo Baeck was in Jerusalem. At that time I had just received an invitation to the Eranos in Ascona for the first time, apparently at Jung's suggestion, and asked Baeck whether I should accept it, since I had since heard and read many complaints about Jung's behavior during the Nazi era. Baeck said: "You absolutely have to go there," and told me the following in the course of our conversation: He, too, had been very repulsed by Jung's reputation, which had emerged from the well-known articles in 1933/1934, precisely because he was Jung, from the Darmstadt meetings of the School of Wisdom, knew very well and would not have believed him to have any National Socialist or anti-Semitic sentiments. When he came back to Switzerland for the first time after his liberation from Theresienstadt (I think it was 1946), he therefore did not visit Jung in Zurich. However, Jung had heard that he was in town and had asked him to visit, which he, Baeck, had refused with reference to those events. Jung then came to see him at the hotel, and they had a two-hour, at times extremely lively, argument in which Baeck accused him of everything he had heard about him. Jung would have defended himself by referring to the special conditions in Germany, but at the same time confessed to him: "Yes, I slipped", which would affect his position on the Nazis and his expectation that something big might break out here. I have vivid memories of this sentence, I slipped, which Baeck repeated to me several times. Baeck said that in this conversation they had cleared up everything that stood between them and that they were divorced again, reconciled. On the basis of this declaration by Baeck, I then also accepted the invitation to the Eranos when it came a second time. [...] Your G .. Scholem »

The strong reception of CG Jung's psychology at the time by German Jews and their subsequent expulsion from Germany probably favored the international spread of Jung's psychology. In 2007 every third Jungian analyst was of Jewish descent, which appears to be a clear contrast to the criticism of Jung's statements about the Jews and his involvement with the National Socialists.

Professorship at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ)

In Switzerland he resumed teaching at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich in 1933 - from 1935 as adjunct professor - which he continued until 1942. In 1934 Jung was elected a member of the Leopoldina .

Friendship with Wolfgang Pauli

Jung met the physicist and Nobel Prize winner Wolfgang Pauli (1900–1958) in 1931 , who came to him because of troubling dreams. From this - over 26 years - a «close intellectual bond» developed. During Pauli's first consultation, Jung noticed that his dreams contained many archetypal motifs. In an attempt to study its development as unaffected as possible, Jung sent Pauli to the young analyst Erna Rosenbaum without interpreting Pauli's dreams. Jung was certain that the young doctor, who did not yet know much about archetypal material, would not disrupt the process of developing the archetypal material through her work. Eight months later, Jung himself and Pauli came into contact again. Jung interpreted a selection of dreams from Pauli's dream series during the first months of the analysis with Ms. Rosenbaum, albeit incognito, in psychology and alchemy. Starting in July 1932, Pauli was personally involved in weekly analysis with Jung for two years. In the following years they discussed his dreams in conversation and in writing. Pauli was a frequent diner of the Jung family and both cultivated a fruitful exchange on diverse topics of natural science, philosophy, religion and psychology, which in an intensive phase between 1946 and 1949 in Jung's essay on synchronicity as a principle of acausal relationships and Pauli's essay on the influence of archetypal ideas on the formation of scientific theories culminated in Kepler . Pauli helped Jung in his search for connections that could form a bridge between psychological and material phenomena and which, according to Jung, manifest themselves in synchronicity events as well as in parapsychological phenomena. In 1955 Niklaus Stoecklin painted a painting by Jung.

Last years of life

In the last years of his life, Jung deepened his research on the collective unconscious , alchemy and the importance of religion for the psyche . After a short illness, Jung died in his house. On June 9, 1961, he was buried in the Dorf cemetery in Küsnacht. For his tombstone he had chosen the saying that he had also chiseled over the threshold of his house: " Vocatus atque non vocatus deus aderit ."

plant

Jung's autobiography Memories, Dreams, Thoughts offers an introduction to his work . There he writes:

«The memory of the external facts of my life has for the most part faded or disappeared. But the encounter with the inner reality, the clash with the unconscious, have etched themselves into my memory and cannot be lost. I can only understand myself from internal events. They are what make my life special, and my autobiography is about them. "

The complete edition of Jung's writings is available in 20 volumes under the title Collected Works by CG Jung , his basic work in a nine-volume edition. His book The Man and His Symbols , first published in English by his colleague Marie-Louise von Franz in 1964, became popular and has been published in many special editions since 1968.

Jung is the founder of analytical psychology within depth psychology . His work cannot be understood if one does not include the relationship between the I and the core of his personality, the self , in psychology. He therefore belongs to a number of depth psychologists who regard self-reference and individuality as the core of the incarnation or of cultural history .

With his work, Carl Gustav Jung influenced not only psychotherapy, but also psychology , religious studies , ethnology , literary studies , art studies and the art therapy that developed from them . In psychology, the concepts of complex , introversion , extraversion and archetype of his personality theory have come into play.

The «Red Book»

In the difficult time after separating from Sigmund Freud, Jung began an experiment with himself, which later became known as "dealing with the unconscious". During this time he made several trips, including to the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico , to the oasis cities of North Africa and the bush savannah of East Africa . For many years he kept his fantasies, which he later called “active imaginations” (this is a “technique developed by Jung to get to the bottom of inner processes”, “to translate emotions into images”, “fantasies that [ [him] moved underground to grasp ”), as notes and sketches in“ black books ”(notebooks).

He later revised these, added reflections and transferred them, together with illustrations in calligraphic script, to a red-bound book, which he titled “LIBER NOVUS”. Jung later developed his well-known theories on the basis of these inner experiences during his confrontation with the unconscious.

The “Red Book”, written between 1914 and 1930, was opened to the public for the first time in 2009 at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York. It was first published in print that same year. The large-format work, which weighs almost seven kilograms and is bound in red leather, is written in a peculiarly solemn German language, in artful calligraphy of medieval manuscripts and provided with colorful illustrations. In Europe, the Red Book was shown for the first time in 2010/2011 at the Museum Rietberg in Zurich. In 2009 the German edition was published by Patmos Verlag, translated by Christian Hermes. In 2017, Patmos published the text, edited by Sonu Shamdasani , without Jung's pictures.

Terms and theories

complex

A complex is a constellation of feelings , thoughts , perceptions and memories that are associatively attracted to the core complex and have gathered centering around that particular significant context. These core complexes are mostly archetypes that arise from the collective unconscious. Complexes can be more or less conscious. Complexes that are repressed in the unconscious can appear in the consciousness as " affect ". An example: A parent complex is the core element of the complex. All feelings, thoughts, perceptions and memories that are directly or indirectly related to the mother are attracted to the core element of the complex and are associated with it. You are thus withdrawn from consciousness and can disturb the conscious intention. Neurotic symptoms can develop from complexes with a negative affect, and there are also positive complexes.

Personality structure

The I or I-consciousness is the center of the field of consciousness and is characterized by a strong identification with itself. Since this I-consciousness consists of a complex of ideas and identifications , Jung also speaks of the so-called I-complex. The ego is not identical with the entire psyche, but "a complex among other complexes".

Outside of this conscious ego complex there are further ego-close complexes, but these are unconscious and in their entirety are referred to as the personal unconscious . These unconscious psychological contents are closely linked to the individual life story and are fed from two different channels. On the one hand, this concerns content that was previously conscious and was subsequently excluded from the self-consciousness as something forgotten or repressed in the further course of the biography . On the other hand, it is primarily unconscious elements that have never or only partially reached consciousness, for example early childhood engrams and subliminally perceived or individually effective contents of the collective unconscious .

«Just as conscious content can disappear into the unconscious, content can also arise from the unconscious. In addition to a multitude of mere memories, really new thoughts and creative ideas can also emerge that were never previously conscious. They grow out of the dark depths like a lotus and form an important part of the subliminal psyche. "

The persona (Latin: mask) is the representative, outward-facing aspect of the self-consciousness. Through his persona, the individual tries to present a picture of his personality that corresponds to his ego ideals in the social space. The persona usually also serves to adapt to the social environment, insofar as one would like to show social behavior at least externally that corresponds to the values and norms applicable there.

The shadow is in a sense the antithesis of persona. The shadow includes personality areas and behaviors that do not correspond to one's own ego ideal and, as a rule, also do not correspond to the explicit values of the social environment. Since the self-awareness mostly does not like to turn to these "dark sides" of one's own personality , the act of acting out one's own shadow sides is usually first mirrored and confronted by the social environment. The shadow is part of the personal unconscious that is close to the self and is made up of all those aspects, inclinations and characteristics of a person that are incompatible with the conscious identifications of the self . As long as the ego has not consciously confronted the multitude of unconscious dark sides, these are typically only seen in other people. This favors the process of projection , as a result of which unfavorable personal characteristics and behaviors are involuntarily “attached” or “accused” to other people, even if this is objectively not or only to a limited extent.

Dealing with the shadow, d. H. Its integration through becoming conscious, acting out or changing, represents an important and indispensable step on the way to becoming whole or individuation of the personality. It represents a predominantly moral problem that requires considerable mental adaptations from the individual. This requires increased performance in introspection and reflection on one's own behavior.

Often from the middle of life the psychological dynamics of the individual life changes, so that the demands of an adaptation to the outside world become less dominant and the inner discussion and differentiation gain in importance. Through this increased turn inwards, parts of the personality of the opposite sex that have hitherto only been seen externally can become more conscious in oneself. For a man this is his anima in its various manifestations and for a woman its animus in its various manifestations. However, the possibility of becoming conscious of the anima or animus is not tied to a stage of life or to an age group.

The collective unconscious - a concept introduced by Jung and strategically directed against Freud's focus on the individual unconscious - forms a common basis for psychological functions for all people. The structures of the ego also develop on the basis of structures of the collective unconscious. In the individual human being, the archetypes of the collective unconscious are shown through archetypal images, i.e. ideas and emotions with a general human basis. This can be seen individually, especially in dreams, and culturally, for example, in mythical motifs, fairy tale motifs and constellations or forms of legends.

The self is both an empirical concept and a theoretical postulate. As an empirical term, it describes, on the one hand, all psychological phenomena in humans. It expresses the unity and wholeness of the total personality. Since the overall personality can only be partially conscious because of the unconscious parts, the term as a postulate includes what can be experienced and inexperienced or not yet experienced. In it all opposing parts of the personality are summarized and unified. The self is the starting point and the goal of the lifelong individuation process, during which more and more areas of the unconscious are incorporated or connected to the consciousness. Individuation always presupposes and sets in motion new and more extensive adaptations of the personality, especially also attitude changes of the consciousness. It takes place on the I-self axis , a term that Erich Neumann introduced as a supplement to Jung's theory.

Archetypes

According to Jung, archetypes are universally existing structures in the soul of all people, regardless of their history and culture. They can be realized differently individually and in societies. Jung noticed that "certain archetypal motifs that are common in alchemy also appear in the dreams of modern people who have no knowledge of alchemy."

Jung's preoccupation with myths, fairy tales and ideas from different times and cultures, which were not influenced by one another, led him to the realization: «The fact is that certain ideas occur almost everywhere and at all times and can even form spontaneously. Completely independent of migration and tradition. They are not made by the individual, they happen to him, yes, they almost impose themselves on the individual consciousness. That is not platonic philosophy, but empirical psychology. " He observed "... typical forms that appear spontaneously and more or less universally, independent of tradition, in myths, fairy tales, fantasies, dreams, visions and delusions". These are not inherited ideas, but "inherited instinctive drives and forms." He called these similarities archetypes , which play a special role in the individuation process of many of his patients. He put this material and, above all, its importance for culture and the individual in connection with the developmental processes of his patients.

But "the true nature of the archetype [...] is not capable of consciousness, that is, it is transcendent, which is why I call it psychoid." As a numinous factor, the archetype "determines the type and sequence of the design [unconscious processes] with an apparent prior knowledge or in the a priori possession of the goal." The archetype is "not just an image in itself, but at the same time dynamis, which manifests itself in the numinosity, the fascinating power, of the archetypal image". It is therefore a matter of “an innate disposition to parallel images, or universal, identical structures of the psyche. ... They correspond to the biological concept of the “pattern of behavior”. In this respect, the archetype can be understood as the meaningful side of the physiological drive. These "structural elements [n] of the human soul" correspond to a "collective spiritual basic layer" of the human being, which surrounds his consciousness.

Archetypes in themselves are non-visual factors in the unconscious psyche that are able to organize ideas, ideas and emotions. Their presence is only evident from their effect; H. in the appearance of archetypal images or symbols . These archetypal images or symbols are each the product of the interaction of the acting archetype in a temporally, spatially and individually determined environment with the individual person and - in contrast to the archetype as an ordering factor - cannot be inherited. For this reason, a careful distinction is necessary between the archetype as such and the archetypal image or symbol, the latter being the result of the arranging effect of the archetype. The growth of a crystal from its mother liquor forms an analogy for this: Archetypal ideas in humans are always individual manifestations. They are just as much to be confused with the collective unconscious as an individual crystal with its original mother liquor from which it grows. Where to close by the manifestations of the unconscious on the hypothetical structures used Jung for the term archetype ( gr. About original form ), but should not be confused with the archetypal images or symbols as individual realizations of the archetypal structure in big variety occur in individuals. The concept of "archetypes" does not imply any conceptual cohesion; H. there is no defined “set” of archetypes, but is in principle open.

The archetype can appear associated with the shadow that relates to semi-conscious or unconscious parts of the personality. It can also be linked to the anima and animus as opposite-sex male or female images for the soul. The archetypes also include the basic forms of the feminine and masculine, also in their religious appearance. For example the archetype of the “hero”, the “father”, “ great mother ”, the “old wise man”, the “divine child”, the “animal god” etc. in their historically well-known and individual forms. The appearance of archetypal content in fantasies and dreams is usually emotionally charged. This can go as far as feeling numb .

Jung described archetypes as energy complexes that also develop their effect in dreams , neuroses and delusions . Jung explains a psychosis that can arise, among other things, when a neurosis is not treated, as the prevalence of the unconscious, which takes hold of the conscious. However, the effective archetypes usually aim to bring the overall personality back into balance by allowing archetypal symbols, accompanied by a strong emotional tone, to rise into consciousness as models. The task of these images and the confrontation of the conscious person with them is to restore a fundamental balance to the personality and to promote meaning and order.

Symbol and sign

Jung wrote: “ In my view, the concept of the symbol is strictly different from the concept of a mere sign. [The symbol ...] always presupposes that the chosen expression is the best possible designation or formula for a relatively unknown fact that is recognized or required as a fact. »He understands symbol as« the expression of a thing that cannot be better characterized in any other way », thus pointing beyond itself. And: "The symbol is only alive as long as it is pregnant with meaning". On the other hand: "an expression that is used for a known thing always remains a mere sign and is never a symbol". A sign is "semiotic" and refers to a clearly delineated state of affairs. From Jung's point of view z. B. a traffic sign or a male or female figure on toilet doors semiotic, d. H. Signs - for example, a cross (unless it denotes an intersection) or a triangle with an eye in it are usually symbols.

The unconscious and the conscious are needed for a symbol to emerge. Thus, both are linked in symbols. «Symbols bring together what is separated, which is also referred to by the Greek root word“ symbols alone ”, which means“ throwing together ”. Living symbols are contact and transition areas, bridges between consciousness and the unconscious. "

Role of psychotherapy

Jung himself sees the psychotherapist as a companion for the patient, who should free himself from all theoretical knowledge he has learned and who should be as free as possible from prejudice to the images, impressions etc. the patient brings with him from his unconscious or developed in the course of therapy. When the patient descended into his own spiritual depths, Jung saw himself as a companion, who at best has more experience and can thus contribute to the success of the respective unique and individual path of the personality concerned to individuation . (Boys therapy)

Psychological types

He referred to a person as extraverted , whose behavior is oriented towards the external, objective world and guided by it. Introverts , on the other hand, are geared towards their inner, subjective world and behave accordingly. Since this differentiation was not sufficient, he developed a model consisting of four functions - thinking, feeling , intuition and feeling - which, combined with the attribute introverted or extroverted , results in eight possibilities, from which eight types can be composed depending on the pairing. He wrote about it in his 1921 work Psychological Types .

- Extraverted thinking is strongly oriented towards objective and external circumstances and is often, but not always, bound to concrete and real facts. People of this type have a high level of legal awareness and demand the same from others. In doing so, they sometimes proceed uncompromisingly, according to the motto "The end justifies the means"; there is a conservative tendency. Due to the subordinate emotional function, they often appear unemotional and impersonal.

- Extraverted feeling is altruistic, fulfills conventions like no other function and has more traditional value standards. If there is too much object influence, this type appears cold, implausible and purpose-oriented and can alternate in his point of view and therefore appear implausible to others. According to Jung, this type is most prone to hysteria.

- extraverted feeling is a vital function with the strongest vital instinct. Such a person is realistic and often pleasure-oriented. If the object is too influenced, his unscrupulous and sometimes naive-ridiculous morality comes to the fore. In neuroses he develops phobias of all kinds with obsessive-compulsive symptoms and is unable to recognize the soul of the object.

- extraverted intuition strives to discover possibilities and sacrifices itself. U. for it; if no further developments are suspected, the possibility can just as quickly be dropped. This type often shows little consideration for the environment. He is easily distracted, does not stick with one thing long enough and therefore sometimes cannot reap the fruits of his labor.

- introverted thinking creates theory for the sake of theory and is not very practical. It is more concerned with developing subjective ideas than with facts. Other people are often perceived as redundant or annoying, which is why these guys appear reckless or cold. This puts them at risk of isolating themselves.

- introverted feeling is difficult to access and is often hidden behind a banal or childish mask. These people are harmoniously inconspicuous and show few emotions, even when they are experienced; Their emotions are not extensive, but intense. In a neurosis, its insidious, cruel side comes to the fore.

- introverted feeling leads to character- related difficulties of expression. People are often calm and passive. Your artistic expression is strong. You move in a mythological world and have a somewhat fantastic and gullible attitude.

- introverted intuition occurs in people who are interested in the background processes of consciousness. Not infrequently they are mystical dreamers or seers on the one hand, dreamers and artists on the other. They try to integrate their visions into their own life. In the case of neurosis, they tend to obsessive-compulsive disorder with a hypochondriac appearance.

Jung classified all thinking and feeling functions as rational and all sensitive and intuitive functions as irrational . Jung's psychological types are used in a modified form with the Myers-Briggs type indicator and socionics . In modern psychology and research, however, Jung's psychological types no longer play a role; they are considered obsolete. Only the terms introverted and extroverted are still used today as technical terms and in everyday language.

Synchronicity

As synchronicity (from Greek synchronous, simultaneous), Carl Gustav Jung described events that were relatively close in time and that were not linked by a causal relationship, but that the observer experienced as meaningfully connected.

Astrology, Alchemy, Psyche and Matter

Connection of psychology and astrology

According to his own statement, CG Jung has been concerned with astrology for decades . In 1911 a letter to Sigmund Freud said:

«My evenings are very busy with astrology. I do horoscope calculations to get on the track of the psychological truth content. So far, some remarkable things that are sure to seem incredible to you. In the case of a lady, the calculations of the star positions resulted in a very specific character image with some detailed fates, which did not belong to her, but to her mother; but there the characteristics sat like a glove. The lady suffers from an extraordinary mother complex . I have to say that in astrology one day a good piece of knowledge about foreboding that has got to heaven could very well be discovered [...]. "

Jung wrote to the Indian astrologer Raman at the end of 1947 that he had been interested in "astrological problems" for "more than 30 years" and that he often consulted the patient's horoscope "for clarification" in the case of difficult psychological diagnoses , "to gain new points of view". In many cases the "astrological information contained an explanation for certain facts which I would otherwise not have understood."

In astrological circles z. B. Jung's work Synchronicity known as a principle of acausal relationships (1952) - published in the book Nature Declaration and Psyche , which he wrote together with the physics Nobel Prize winner Wolfgang Pauli . In an "astrological statistics" he investigated a. a. a large series of natal charts of married and unmarried persons pointing to a "marriage" constellation: with regard to the sun and moon compared to other aspects between sun and moon, Mars and Venus, ascendant and descendant , he actually meant a higher proportional share of the «Sun-moon connection» to be found in married people compared to the comparative horoscopes of unmarried people. From his point of view, later "check-ups" that he himself carried out did not confirm this connection. He then assumed that in a “synchronistic context” the “statistical results” depend on the respective (subliminal) expectations of the researcher. From then on he rejected scientific attempts at proof in favor of astrology and certified that statistical methods as a whole had a fundamentally "ruinous influence" on "coincidences" and "synchronicity processes".

Understanding of alchemy

Jung understood occidental alchemy as representations of alchemists who experienced their own projected unconscious in the material. The alchemists oriented themselves accordingly to their dreams and visions in order to get to the secret of the substance, but they did not yet know how to get there. So they found themselves in a parallel situation to modern humans who want to explore the unknown of the unconscious psyche. The alchemists saw inorganic matter as a living unknown, and in order to study it, one had to establish a relationship with it. They used dreams, meditation exercises and the phantasia vera et non phantastica, which largely corresponded to what Jung had developed as an active imagination .

In terms of religious history, Jung saw the work of alchemy as an attempt to further develop Christianity. It forms “something like an undercurrent to the Christianity that dominates the surface. Like the dream it relates to consciousness, and just as the latter compensates for the conflicts of consciousness, so does the one who endeavors to fill in the gaps which the conflicting tension of Christianity has left open »

For Jung, an important motif in alchemy is that of the “king's renewal”. She describes the "change of the king from an imperfect state to a healed, perfect, whole and corrupt being." Psychologically, the king is a symbol for consciousness as well as for the spiritual and religious dominant idea of a culture. With the alchemists it was the medieval Christian worldview. This had become inadequate for her because she lacked the dark, chthonic aspect of nature and "the relationship to the image of God in creation, the natural feeling of antiquity". The union (in the alchemist's term: coniunctio) of Rex (Sol = sun) and Regina (Luna = moon) means the union of the day principle, symbol for the lightful consciousness with the night light, symbol for the unconscious. At the individual level, this initially leads to a kind of dissolution of the self-consciousness and thus to disorientation (Latin = "nigredo"), but then to a new birth, i. H. a renewed consciousness. "The renewed consciousness does not contain the unconscious, but forms a whole with it, which is symbolized by the Son." The Son embodies a new attitude of consciousness that does justice to both the conscious and the unconscious, and corresponds to a future conception of God. For the alchemists this is the “well-guarded, precious secret of the individual”.

The "spirit of matter", the alchemical figure of "Mercurius", referred to by the alchemists as a kind of earthly god, was understood by Jung as a hidden, divine-human creative spirit, which many people today can find in the depths of their own souls. Mercurius "embodies everything that is lacking in the Christian image of God, i.e. H. also the areas of matter and the body "and be a symbol that unites the opposites, that" can bring the new light when the (Christian) light has gone out ".

Psyche and matter

Jung saw both spirit and matter as archetypal and ultimately transcendent of consciousness. In his view, both can be described by the traces they leave behind in the human psyche, because for him only the psychic experience was the only thing that was immediately given for the human being. But he also thought it possible that matter itself could be animated. He referred to the psyche a. a. as a quality aspect of matter: “The psyche is not something different from a living being. It is the psychological aspect of the living being. It is even the psychological aspect of matter ». “We discover that matter has another aspect, namely a psychological one. That is the world viewed from within. " It is as if, from the inside, one sees another aspect of matter. He presented his thoughts on the subject to v. a. in his works Theoretical Considerations on the Essence of the Psychic (1946), Synchronicity as a Principle of Acausal Relationships (1952) and Mysterium Coniunctionis (1956).

spirituality

Through his work with patients and through personal experience, Jung came to the conviction that life must have a spiritual meaning that points beyond the material realm. Jung viewed religion as an original, archetypal manifestation of the collective unconscious. He was of the opinion that the development of one's own personality, individuation, is facilitated by religion. Individuation is a path to oneself and, precisely in it, a path to the divine in man, to God. Jung recognized that many modern people in particular have little spiritual support and therefore need a sense of purpose in their lives. Spiritual experiences can make a significant contribution to this by having a meaningful effect on the psyche. Jung therefore dealt in detail with religious experiences, for example with the figure of the Old Testament Job (Job) or with the life of the Swiss hermit Niklaus von Flüe .

Because of his therapeutic experiences, Jung, in contrast to Freud, assumed a transcendent, spiritual dimension in people. This led him to believe that spiritual experiences are essential to our emotional wellbeing. Jung's idea of religion as a practical aid to individuation has met and is widely accepted. It has been included in relevant treatises on the psychology of religion , but has also repeatedly been critically questioned from various quarters (e.g. from Martin Buber or from dialectical theology) (see section Criticism).

aftermath

CG Jung's collected works have been translated into numerous other languages. Over the past 100 years, analyst associations and training centers for analysts from the Jungian school have emerged worldwide.

psychology

CG Jung's work played a comparatively minor role in the further development of depth psychological currents. For example, while a subsequent trend such as neopsychoanalysis has in many respects tied in with the concepts of Sigmund Freud's classical psychoanalysis and Alfred Adler's individual psychology, Jung's analytical psychology was barely noticed by its representatives.

The Jungian Anthony Stevens calls the distinction between introverted and extraverted attitude types the aspect of Jungian typology that has found the broadest acceptance. Attempts to put Jung's four types of functions on an empirical basis were less successful, however.

But as little as Jung's influence in many fields of depth psychology may be, the greater its effect in marginal areas and controversial currents within academic psychology and even more outside of it. For example, CG Jung is honored with an own contribution in the anthology Klassiker der Religionswissenschaft by Christoph Morgenthaler. To this day, his draft is regarded as an important contribution within the psychology of religion, as in Susanne Heine's Fundamentals of Psychology of Religion.

Jung's importance for the development of transpersonal psychology , which is specifically devoted to human spiritual experiences, should also be mentioned. Jürgen Kriz understands Jung's analytical psychology in his essay Transpersonal Psychologie for the concise dictionary Psychology as a classic approach of transpersonal psychology.

There are hardly any known students of CG Jungs who have had a strong impact (see analytical psychology ). However, some better-known psychotherapists have made their own reform of analytical psychology. They include:

Karlfried Graf Dürckheim : With his initiatic therapy he expanded Jung's analytical psychology to include aspects of gestalt psychology and body psychotherapy . Alongside CG Jung, Dürckheim is also considered a classic of transpersonal psychology.

Paul Watzlawick : One of the most famous representatives of systemic psychology. Watzlawick was trained as a psychotherapist at the CG Jung Institute in Zurich.

The dance / movement as active imagination, created in 1916 by CG Jung and Toni Wolff, and successfully from was Tina Keller Jenny and other analysts as Trudi Schoop and Marian Chace practiced and developed.