spiritism

Spiritualism ( lat. Spirit , mind '), sometimes in German due to incorrect translation of the English spiritualism as Spiritualism spent called modern forms of invocation of spirits or haunted ghosts , particularly spirits of the dead ( necromancy ), which with the help of a medium perceptible should communicate.

Outside of German usage, the term spiritualism is more narrowly defined as a term for the teaching of the spiritualist Allan Kardec .

Concept history

Through German idealism , the term Geist became known as a collective singular within the German-speaking discourse. This newly discovered term was divided up in the course of the 19th century, so that on the one hand the concept of spirit within philosophy appeared in the discourse as Weltgeist , Zeitgeist or Volksgeist . In terms of history , the singular term goes back primarily to Johann Gottfried Herder , who used the word Geist for Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu's term esprit in German. This word was then taken up by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and found expression in the idealistic topoi of Weltgeist and Volksgeist . On the other hand, the plural spirits also became common, especially in the area of esotericism . During this time, the word ghosts became known primarily because it was used as a translation of various Greek words without having any direct German-language content. The most important of these Greek words are anima , pneuma and spiritus . As an independent German word, Geister took on the meanings that are also contained in the Greek word Pneuma: an intermediate being from the Hebrew-Jewish tradition, a subtle bond between body and soul, a protective light aura around the human body, a cosmic principle and a connection to God that allows one to gain mystical knowledge or supernatural abilities.

history

Forerunner of "modern spiritism"

In the English-speaking world, media were already active before 1848, claiming to be able to establish contact with the world of the deceased. These include William Stainton Moses , who defined spiritualists as those who have established for themselves or see it as evidently correct that death does not kill the spirit, but that it survives. In addition, there were the events around Andrew Jackson Davis , who published his work The Principles of Nature as early as 1847 and thus published a complete work of spiritualistic philosophy before the Fox sisters, which, however, in contrast to the writings published after 1848, is classified as mesmerism .

In the German-speaking countries, mesmerism played a major role, the methods of which were supposed to lead to phenomena similar to those in the spiritistic seances. This was accompanied by a trend that led to the fact that supernatural phenomena were subjected to scientific research more than in other countries.

Emergence

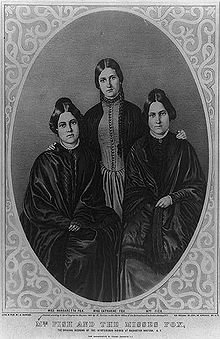

The emergence of modern spiritualism is usually associated with the sisters Margaret and Kate Fox and their parents, who in 1848 claimed to hear strange knocking noises in a recently relocated house in Hydesville, New York , which killed them in the spirit of one and attributed to peddler buried in the basement . The family adopted the long-established technique of “communication” with such “knocking spirits”, in which each letter in the alphabet is assigned a certain number of knocking symbols, and sought publicity with great success. The first public demonstration of the girls' "skills" in Rochester , New York, in November 1848, was attended by 400 paying guests. Such media soon appeared elsewhere, mainly in the evangelical north-east of the USA, and at the height of this wave around 1855, one to several million Americans are said to have been convinced of the reality of the alleged necromancy. In the process, new methods of “communication” with the spirits spread quickly, such as “automatic writing”, in which the spirit should guide the hand of the medium, or the expression of the spirits' thoughts through media put into trance .

The novelty that distinguished modern spiritualism from similar older practices was the great interest that a broad public showed in it. Antoine Faivre points out that the spiritism about the same time with the classic fantasy literature and the social utopia of Marxism occurred and that just before the big hype about the Fox sisters, the book The Principles of Revelation by Andrew Jackson Davis (1847) in had appeared in the USA. Davis combined ideas of mesmerism and early socialist Fourierism. Mesmerism also tried, albeit in a somewhat different way (“ magnetization ”), to obtain information from a supernatural world with the help of media. Other important aspects of prehistory were the mystical teaching of Emanuel Swedenborg and the "communications" with higher spiritual beings that were common in French illuminism in the late 18th century. In 1826 , Justinus Kerner caused a considerable sensation in the German-speaking area by “magnetizing” the later so-called seer of Prevorst and thus making her communicate with the spirits of the deceased, evoke “knocking spirit” appearances and preach teachings received from higher spiritual beings . As early as 1794, Johann Caspar Lavater had reported on spiritualistic sessions.

Spread

The wave of spiritualism triggered by the Fox sisters quickly spread throughout Europe, where the French Allan Kardec (1804–1869), the first major theorist of this movement, founded a religion based on spiritism and the belief in reincarnation . This spread of spiritualism, as the historian James Webb notes, coincided with a “return of the miracle to the religious life of Europe”, which was shown in numerous reports of apparitions of Mary , miraculous healings or levitations . Spiritist ideas were often intertwined with ideas of social reform, especially with those of the early French socialists . These connections, as the Davis example illustrates, had been prepared as early as the 1840s. After 1848, spiritualism was significantly shaped by (former) Saint-Simonists and especially by Fourierists.

In Germany, the spiritist movement gained a foothold relatively slowly and did not develop into a mass movement, but on the other hand met with greater interest in intellectual and scientific circles than in other countries, with influential scientists sometimes vehemently opposing it. In the late 1850s, the German botanist and natural philosopher Christian Gottfried Nees von Esenbeck , who had been dealing with " animal magnetism " for a long time , became aware of the spiritualistic writings of Andrew Jackson Davis and had them translated into German by the Catholic theologian Gregor Konstantin Wittig. This gave rise to the Library of Spiritualism for Germany , which Wittig published from 1868 and which made Spiritualism known to a broader German-speaking readership. In 1873 Wittig founded a spiritist association in Leipzig, and from 1874 on, together with the Russian spiritist Alexander Aksakow and the publisher Oswald Mutze, he published the journal Psychische Studien , which for a long time was the most important occult journal in Germany.

In 1877, the Leipzig astrophysicist Karl Friedrich Zöllner organized several séances with the American medium Henry Slade , in which Gustav Theodor Fechner and a few other scientists also took part. Slade apparently telekinetically set objects in motion and made written messages appear on slates. Zöllner regarded this as empirical confirmation of his long-cherished assumption of a fourth dimension of space and published detailed reports on these experiments in 1878/79, to which he added the hypothesis that spiritual beings from the fourth dimension caused the observed phenomena. In doing so, he hoped to establish a “transcendental physics” and, after an English translation of his publications on the subject had appeared in 1880, triggered an international debate.

In the press and in scientific circles, Zöllner met mostly with severe criticism. He was accused of abusing his authority as a renowned scientist in order to make spiritualist superstition socially acceptable, and he was even described as insane. A prominent critic was the psychologist Wilhelm Wundt , who had attended one of the séances and expressed doubts about the authenticity of the phenomena produced by Slade. (In fact, Slade had been convicted of fraud in Great Britain as early as 1876 and escaped punishment by fleeing abroad.) Wundt criticized Zöllner's gullibility and described the belief that séances could provide evidence of life after death as a relapse into barbarism . (Similar debates had previously taken place in Britain, with chemist William Crookes and naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace playing a role similar to that of customs officers.)

From the early 1880s onwards, Wittig and Aksakow developed a new way of looking at Spiritism, known as "animistic". While the phenomena occurring at séances were traditionally interpreted as expressions of the deceased, the animists assumed that the actual underlying factors were unknown and amenable to psychological research. They found a renowned supporter in the philosopher Eduard von Hartmann , who was known as the author of a Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869) and who, in his 1885 book Der Spiritismus, advocated a scientific investigation of Spiritism. Although he largely shared Wundt's criticism of the practices in spiritualist circles, Hartmann hoped that serious investigations would provide insights into the workings of the unconscious , and one could also study people's tendency towards superstition and belief in miracles in this area. This new direction, from which parapsychology emerged , was opposed to traditional spiritualism, whose leading representatives in Germany at that time Wilhelm Besser and Bernhard Cyriax published the magazines talk room and [Neue] Spiritualistische Blätter and which was organized in many associations.

The conflict between these two directions came to a head when media emerged that not only produced knocking noises and verbal and written communications, but also "materialized" objects seemingly out of nowhere, causing a sensation. These materializations triggered particularly violent critical reactions in circles devoted to the scientific investigation of mediumism on the psychological level ("psychological" research). There were indictments and convictions for fraud, with the Anna Rothe case (convicted in 1903) in particular receiving considerable echo in the press across the country, as Rothe had previously appeared and participated in many German cities as well as in Vienna, Zurich and Paris for several years had gained an enthusiastic following.

Decline of movement

When the icon of spiritualism, Margaret Fox, forty years after the events in Hydesville, publicly admitted to having brought about all the haunted and knocking noises with her sisters, and when many other of the alleged spirit communications also turned out to be fraud, the spiritualist lost Move their reputation in the population. Until the end of her life, Fox gave lectures on the deceptions of her life, but the seances faked with her sisters and professional accomplices had long since found so many imitators among millions of spiritism enthusiasts that an entire branch of industry had already formed to meet the demand for animation props to satisfy.

The magicians and illusionists were among the greatest adversaries of the spiritualistic media because they were quick to see through the tricks and impostures of the media. One of the most famous of these magicians who devoted himself to unmasking spiritualistic illusions was Erik Weisz, known as Harry Houdini , who in his reveal book A Magician Among the Spirits documented the deceitful methods of the spiritualistic media and clairvoyants such as automatic writing, moving tables , ghost manifestations and levitation.

In addition, from the 1860s onwards, spiritualism failed because of its own claim to be a science and to be measured by this standard. For example, in 1857 the attempt to prove it before a scientific committee in Great Britain, in which Kate Fox appeared as a medium, among others, failed. In Europe, media presentations increasingly turned into fairs, so that both the religious and scientific claims that were originally pursued could no longer be upheld.

Spiritism as a religion

As a religion, Spiritism is characterized by a pronounced scientistic attitude and a sharp rejection of traditional Christianity . Fundamental is the conviction that the human soul continues to exist after death and that it is possible with the help of media to communicate with the souls of the deceased. The deceased therefore differ only little from their earlier earthly existence, retain their peculiarities, and the “other world” in which they live is similar to this world, although it is “better” in some respects. Originally connected with this was the conviction that the existence of souls or spirits could be proven by means of scientific experiments. Wilhelm Wundt therefore described spiritualism as a form of materialism that calls itself " spiritual " and wants to be an alternative to conventional materialism, but represents the spiritual materially. The relationship to Christianity is similarly ambivalent, since spiritualists often describe themselves as Christians, but firmly reject traditional Christianity.

Spiritism is estimated to have over 100 million followers worldwide. It is most widespread in Brazil , where Kardecism is very popular , partly in connection with Afro-Brazilian religions such as Umbanda and Candomblé .

literature

- Catherine L. Albanese: A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion . Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2007.

- Ruth Brandon: The Spiritualists. The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries . Prometheus Books, New York 1983, ISBN 0-87975-269-6 .

- Daniel Cyranka : Religious Revolutionaries and Spiritualism in Germany Around 1848 . In: Aries 16/1, pp. 13-48.

- John Warne Monroe: Laboratories of Faith: Mesmerism, Spiritism, and Occultism in Modern France . Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2008.

- Robert L. Moore: Spiritualism . In: Edwin S. Gaustad (Ed.): The Rise of Adventism. Religion and Society in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America . Harper Row, New York 1974, ISBN 0-06-063094-9 , pp. 79-103.

- Robert L. Moore: In Search of White Crows. Spiritualism, Parapsychology, and American Culture. Oxford University Press, New York 1977.

- Christopher M. Moreman (ed.): The Spritualist Movement. Speaking with the Dead in America and Around the World. 3 vols., ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2013.

- Geoffrey K. Nelson: Spiritualism and Society . Routledge Paul, London 1969.

- Janet Oppenheim: The Other World. Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850-1914 . University Press, Cambridge 1985, ISBN 0-521-26505-3 .

- Diethard Sawicki: Living with the dead: belief in spirits and the emergence of Spiritism in Germany 1770-1900 . Schöningh, Paderborn 2001, ISBN 3-506-77590-1 (plus dissertation, University of Bochum 2000).

- Julian Strube: Socialism, Catholicism and Occultism in France in the 19th Century . De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-047810-5 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Horst E. Miers : Lexicon of Secret Knowledge (= Esoteric. Vol. 12179). Original edition; and 3rd updated edition, both Goldmann, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-442-12179-5 , p. 585.

- ↑ Diethard Sawicki: Living with the dead: belief in spirits and the emergence of spiritism in Germany 1770-1900 . Schöningh, Paderborn 2001, ISBN 3-506-77590-1 , p. 14

- ↑ Diethard Sawicki: Living with the dead: belief in spirits and the emergence of spiritism in Germany 1770-1900 . Schöningh, Paderborn 2001, ISBN 3-506-77590-1 , p. 17

- ^ "Spiritualism" in: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology 5th Edition, p. 1463

- ^ "Spiritualism" in: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology 5th Edition, pp. 1468 ff.

- ↑ John Patrick Deveney: Spiritualism , in: Wouter Hanegraaff (ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism , Leiden 2005, p 1075f; Kocku von Stuckrad : What is esotericism? , Munich 2004, p. 201

- ^ Catherine L. Albanese: A Republic of Mind and Spirit: A Cultural History of American Metaphysical Religion . Yale University Press, New Haven / London 2007, pp. 171-176, 208-218.

- ↑ Wouter J. Hanegraaff : New Age Religion and Western Culture , Leiden 1996, p. 436f; Antoine Faivre: Esoteric Overview , Freiburg 2001, p. 109f; Stuckrad, p. 201f

- ↑ John Patrick Deveney: Spiritualism, in: Wouter Hanegraaff (ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism, Leiden 2005, pp 1079-1081; Stuckrad, p. 202; Faivre, pp. 109f

- ↑ James Webb : Die Flucht vor der Vernunft , Wiesbaden 2009, pp. 222–230; Quote p. 229

- ^ Julian Strube: Socialist Religion and the Emergence of Occultism. A Genealogical Approach to Socialism and Secularization in 19th-Century France . In: Religion 2016.

- ^ John Warne Monroe: Laboratories of Faith: Mesmerism, Spiritism, and Occultism in Modern France . Cornell University Press, Ithaca 2008, pp. 48-63.

- ↑ John Patrick Deveney: Spiritualism, in: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism, Leiden 2005, p. 1080f.

- ^ Helmut Zander: Anthroposophy in Germany. 2007, pp. 929f.

- ^ Corinna Treitel: A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern , Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London 2004, p. 38f.

- ^ Daniel Cyranka: Religious Revolutionaries and Spiritualism in Germany Around 1848 . In: Aries 16/1, pp. 13-48.

- ↑ Corinna Treitel: A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern , Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London 2004, pp. 3–9.

- ↑ Corinna Treitel: A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern , Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London 2004, pp. 10-13.

- ^ Corinna Treitel: A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern , Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London 2004, p. 3.

- ↑ On Wallace see Ulrich Kutschera : Design Errors in Nature. Alfred Russel Wallace and the godless evolution , LIT-Verlag, Berlin 2013, pp. 129–156

- ^ A b Corinna Treitel: A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern , Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Corinna Treitel: A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern , Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London 2004, pp. 13-15.

- ^ Corinna Treitel: A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern , Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London 2004, p. 171.

- ↑ Corinna Treitel: A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern , Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London 2004, pp. 165–174.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad: What is esotericism? Beck, Munich 2004, p. 201.

- ↑ Linus Hauser: Critique of the neo-mythical reason , Vol. 1: People as gods of the earth . Schöningh, Paderborn 2004, pp. 249 and 252-253.

- ↑ Linus Hauser: Critique of the neo-mythical reason , Vol. 1: People as gods of the earth . Schöningh, Paderborn 2004, pp. 249 and 254.

- ^ Harry Houdini : A Magician Among the Spirits. Intl Law & Taxation Publication 2002.

- ^ "Spiritualism" in: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology 5th Edition, pp. 1476 ff.

- ↑ Diethard Sawicki: Living with the dead: belief in spirits and the emergence of spiritism in Germany 1770-1900 . Schöningh, Paderborn 2001, ISBN 3-506-77590-1 , p. 331 ff.

- ↑ Hanegraaff, pp. 438-441

- ↑ Stuckrad, p. 202

- ↑ John Patrick Deveney: Spiritualism, in: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism, Leiden 2005, p. 1081.