Esoteric

Esotericism (from ancient Greek ἐσωτερικός esōterikós ' inwardly ', belonging to the inner realm') is in the original meaning of the term a philosophical teaching that is only accessible to a limited “inner” group of people, in contrast to exotericism as generally accessible knowledge. Other traditional meanings of the word refer to an inner, spiritual path of knowledge, for example synonymous with mysticism , or to a “higher”, “absolute” knowledge.

Today there is no generally accepted definition of esoteric or esoteric, neither in scientific nor in popular usage .

In science , two fundamentally different uses of these terms have been established:

- The Religious Studies describes and classifies various forms of religious activity she summarizes as esoteric.

- The science of history is concerned, however, with certain trends of Western culture , which have certain similarities and associated historically with each other.

In popular usage , esotericism is often understood as "secret doctrines". Also very common is the reference to "higher" knowledge and the paths that should lead to it. Furthermore, the adjective "esoteric" is often used pejoratively in the sense of "incomprehensible" or "spun".

Concept history

Antiquity

The ancient Greek adjective esoterikos is first attested in the 2nd century: in Galen , who called certain stoic teachings that way, and in a satire by Lucian of Samosata , where "esoteric" and "exoteric" refer to two aspects of the teachings of Aristotle (from inside or outside). The opposite term "exoteric" is much older: Aristotle (384–322 BC) called his propaedeutic courses, which are suitable for non-specialists and beginners, "exoteric" (outwardly directed) and thus distinguishes them from strictly scientific philosophical teaching. Only Cicero (106–43 BC) refers the term “exoteric” to a certain genre of writings by Aristotle and the Peripatetic , namely the “popularly written” works intended for the public (literary dialogues) in contrast to the only specialist publications suitable for internal use in schools; but he does not call the latter “esoteric”. In the sense of this classification of the literature made by Cicero, which does not go back to Aristotle himself, the "exoteric" from the "esoteric" writings of Aristotle are still distinguished today in ancient studies. The “esoteric” writings do not contain any secret doctrines, but only statements, the understanding of which requires a prior philosophical education. Aristotle's teacher Plato was already convinced that some of his teachings were unsuitable for publication ( unwritten teaching ). That is why the modern research literature speaks of Plato's "esotericism" or "esoteric philosophy", by which the unwritten doctrine is meant.

The church father Clemens of Alexandria first used the term esoteric to mean “secret” . In a similar sense, Hippolytus of Rome and Iamblichus of Chalkis differentiated between exoteric and esoteric students of Pythagoras , the latter forming an inner circle and receiving certain teachings exclusively. The Greek word was only adopted into Latin in late antiquity ; the only ancient evidence for the Latin adjective esotericus is a passage in a letter from the church father Augustine , who wrote about "esoteric philosophy" following Cicero's statements with reference to Aristotle.

Common usage in modern times

The starting point for the emergence of the modern term esoteric was the Pythagorean use of the term Iamblichus. One thought of the division of the Pythagoreans into the two rival groups of the " acousmatists " and the "mathematicians", both of whom are said to have claimed to represent the authentic teaching of Pythagoras, which was handed down by Iamblichus and which is controversial in modern research . Whether there actually was a secret doctrine of the early Pythagoreans is disputed in research, but the idea of it was widespread in the early modern period and coined the term "esoteric". This word was used to denote secret knowledge that a teacher only shares with selected students.

In English, the word first appears in the History of Philosophy by Thomas Stanley, published 1655–1662 . Stanley wrote that the inner circle of the Pythagoreans was formed by the Esotericks . In French, ésotérique is first attested in 1752 in the Dictionnaire de Trévoux , and in 1755 in the Encyclopédie . In German, “esoteric” is a foreign word, probably taken from French or English, first documented in 1772; From the late 18th century onwards, the adjective was used to denote teachings and knowledge that are only intended for a select group of initiates or worthy people, as well as to characterize scientific and philosophical texts that are understandable only to a small, exclusive group of experts . A derogatory connotation has been widespread since the 20th century ; “Esoteric” often means “incomprehensible”, “secretive”, “unworldly”, “spun”. (See also esoteric programming languages .) The noun “esoteric” is in use from the early 19th century (first reference 1813); initially it referred to a person who is initiated into the secrets of a society or the rules of an art or science.

The use of the noun "esoteric" (French ésotérisme ) begins in 1828 in a book by Jacques Matter about the ancient gnosis. After other authors had also taken up this neologism , it was first listed in a French universal dictionary in 1852 as a name for secret doctrines. The word became widely used through the influential books of Éliphas Lévi on magic , from where it found its way into the vocabulary of occultism . Since then it has been used (like the adjective) by many authors and trends as a self-designation, often freely redefining it.

Today, “esotericism” is widely understood as a term for “secret doctrines”, although according to Antoine Faivre it is de facto mostly generally accessible “open secrets” that can be opened up by a corresponding effort of knowledge. According to another, also very common meaning, the word refers to a higher level of knowledge, to “essential”, “actual” or “absolute” knowledge and to the very diverse paths that should lead to this.

Scientific usage

In science, two fundamentally different uses of the term esoteric or esoteric have become established:

- In the context of religious studies , it is usually defined typologically and relates to forms of religious activity that are characterized in a certain way. Often these are secret teachings, corresponding to the original meaning of esotericism. Another, related tradition, represented by Mircea Eliade , Henry Corbin and Carl Gustav Jung , relates “esoterically” to the deeper, “inner secrets” of religion in contrast to its exoteric dimensions such as social institutions and official dogmas .

- This is to be distinguished from historical approaches, which summarize certain currents, especially of Western culture, as esotericism, which have certain similarities and are historically linked. In this context, Western esotericism has mostly been spoken of recently . In some cases, the time frame is still limited by speaking of esotericism only in modern times; other authors also add corresponding phenomena in the Middle Ages and in late antiquity. There is still no consensus regarding the exact delimitation of the term, but there is a consensus regarding the core areas. These include the rediscovery of hermetics in the Renaissance , the so-called occult philosophy with its broadly Neoplatonic context, alchemy , Paracelsism , Rosicrucianism , Christian Kabbalah , Christian theosophy , illuminism and numerous occult and other currents in the 19th and 20th centuries up to the New Age movement. If one also includes earlier times, the ancient gnosis and hermetics, the Neoplatonic theurgy and the various occult “sciences” and magical currents are added, which then merged into a synthesis in the Renaissance. In this perspective, the aforementioned distinction between the two fundamental religious studies approaches does not play a role, since both the aspect of secrecy and that of the "inner path" can be present or absent in phenomena that are esoteric from a historical perspective. However, there are also approaches in which typological and historical elements are combined.

History of Western Esotericism

Antiquity

The first evidence of doctrines and social structures that can be attributed to esotericism from today's point of view can be found quite early in ancient Greece and in southern Italy , which was then Greek-populated , with Pythagoras (* around 570; † after 510 BC) as the founder of religious-philosophical school and brotherhood of the Pythagoreans in Croton (today Crotone ) particularly stands out. Pythagoras believed - just like the Orphics and followers of various mystery cults - in the immortality of the soul. The Pythagoreans and the Orphics associated this with the idea of transmigration of souls ( reincarnation ). They viewed the body as a temporary dwelling for the soul, even as a dungeon from which it had to free itself. They strived for this redemption from physical existence through a morally impeccable life, which should first lead to a rebirth on a higher level, but finally to the final liberation from the physical world by ending the series of rebirths. These ideas were in sharp contrast to the older view represented by Homer , in whose Iliad the concept of the soul ( psyche ) appears for the first time, but only as an attribute of the person fully identified with the body. Other important philosophers such as Empedocles and Plato, as well as all ancient Platonists, were later adherents of the idea of reincarnation .

Another central motif of esotericism, which appeared for the first time among the Pythagoreans, is the elevation of numbers to the principles of all beings. They viewed the world as a unit ( cosmos ), harmoniously ordered according to integer proportions , and they saw the path to the purification of the soul in submission to the general, mathematically expressible harmony of all things. The idea of the musically based harmony of the spheres , based on a comparison of the planetary movements with the numerical relationships of the musical intervals discovered by the Pythagoreans , also originated here. Numbers were even given a moral aspect by assigning certain numbers to moral qualities such as justice or discord.

Plato (427–347 BC) was the first to try to prove the immortality of the soul argumentatively (in his dialogue Phaedo ). In doing so, he identified the soul with reason , which he regarded as fundamentally independent of the body. Her real home is the realm of immortal ideas and pure spirits, from which she comes and to which she returns after death. As with the Pythagoreans, the body appears here as a prison from which the soul can escape in the series of rebirths through a pure lifestyle and pass into a purely spiritual existence. Unincarnated, she can therefore directly see the eternal beings to which she belongs, while this knowledge is darkened in the body and usually only appears like a memory in the course of the self-established activity of reason. In addition to the living beings, Plato also attributed the stars and the cosmos as a whole of its own souls and thus life.

Plato's philosophy was also esoteric in the sense that it pointed to an inner path. According to Plato, the essence of his teaching cannot be communicated at all, but only accessible to one's own experience. As a teacher, he could only give hints on the basis of which a chosen few would be able to develop this esoteric knowledge for themselves, which in such cases suddenly arises as an idea in the soul and then continues to break its path.

The motif of an inner circle of "initiates" ( Grundmann ) or chosen ones, partly connected with the call for secrecy ( Arcane discipline ), also occurs frequently in the early Christian writings, which were later incorporated into the New Testament as Gospels , although a certain group of people is not always meant. In this respect, one can speak of New Testament approaches to Christian esotericism, as the esoteric researcher Gerhard Wehr does. Opposite these personally chosen by Jesus is the apostle Paul , who had never met Jesus personally and who even vehemently opposed his followers, but who was converted to Christianity through an inner revelation (“ Damascus experience”) and finally became its most successful missionary. Here Wehr speaks of "Pauline esotericism" in the sense of the inner path. Paul claimed to have received the “ Pneuma ” (spirit) of God and therefore to know the essence and will of God, because the spirit fathoms (unlike human wisdom) everything, “including the depths of God”. The Gospel of John and the Revelation of John , which the philosopher Leopold Ziegler , for example, described as "a thoroughly esoteric literature" have a special position among the writings of the New Testament . This special position was already expressed in early Christianity when the Gospel of John was distinguished from the others as the “spiritual” or “pneumatic” Gospel ( Clement of Alexandria , Origen ).

Plato's theory of the soul was followed by Neo-Platonism in post-Christian times , the most prominent representative of which was Plotinus, who worked in Rome (205–270 AD), and which is considered to be the most important philosophical trend in late antiquity. Plotinus drew the utmost consequence from Plato's approach by describing the ecstatic upswing to " one ", as he called the divine, the awareness of the source of all things in ourselves, as the "true ultimate goal for the soul". “At its highest point, Plotin's thinking proves to be mysticism ”, as the philosopher Wolfgang Röd writes, and the esoteric researcher Kocku von Stuckrad sees here the “ Archimedean point of European interpretation of the soul” and the “fulcrum of today's esoteric views” such as the New Age Movement. This mystical element, combined with magical practices, emerged even more strongly than in Plotinus in later Neo-Platonists such as Iamblichus (around 275–330 AD) and Proclus (5th century). These philosophers followed the interest in mystical religiosity, magic and divination , which was very widespread at that time . In this context, Röd speaks of a transformation of Neoplatonic philosophy "into a kind of theosophy and theurgy ".

Another tradition founded in Hellenistic antiquity, which was to acquire great significance for esotericism, is Hermetics , which refers to the revelations of the god Hermes and represents a synthesis of Greek philosophy with Egyptian mythology and magic. Here the motif of the mediator, which until then was little known in Greco-Roman thought, came to the fore, who - whether as god or as an "ascended" human being - reveals higher knowledge. Another basic motif of hermetics as well as of later esotericism in general is the idea of an all-connecting sympathy , which should justify the astrological correspondence between macrocosm and microcosm. Later the Neoplatonic concept of the ascent of the immortal soul through the planetary spheres and the associated redemption up to becoming one with God, made possible through knowledge and the fulfillment of certain ethical requirements.

The idea of the redemption of the soul through higher knowledge experienced a special expression in various religious currents of late antiquity, which are collectively referred to as gnosis . This diverse movement arose in the first century AD in the east of the Roman Empire and in Egypt. It appeared in pagan, Jewish, and Christian varieties. It combined elements of Greek philosophy with religious ideas. A sharp dualism was usually the basis , i.e. H. a sharp separation between the spiritual world, from which the human soul originates, and the basically void material world to which it is temporarily bound - also understood as the opposition of light and darkness or of good and evil. From this point of view, the sacred religious scriptures were viewed as encrypted messages that had been written by " pneumatics " to whom the higher knowledge of spiritual reality was accessible and that only pneumatics could really understand. In Christian Gnosis in particular, the redeeming figure of Christ and the associated idea of a decisive turning point in world history also appeared.

Gnosis encountered increasing opposition both from the philosophical side (especially Plotinus) as well as from the established and institutionally consolidating large Christian church, although a sharp distinction between the emerging ecclesiastical theology and the heterogeneous varieties of Christian gnosis was and is hardly possible . The influential theologians Clemens and Origen were close to Gnosis in that they too propagated a higher, “spiritual” knowledge and claimed it for themselves, and Origen was even called the “head of the heretics ” by his later opponent Epiphanius von Salamis . Another problem is that the terms “gnosis” and “gnosticism” were essentially coined by the ecclesiastical opponents, while those named themselves mostly simply called “Christians” or even “ orthodox ” Christians. An essential difference between the ecclesiastical critics and those of these so-called Gnostics was that the latter emphasized the individual's own knowledge (Greek gnosis ) and propagated a "self-empowerment of the knowing subject" (Stuckrad), while the Church placed great emphasis on the Limitation of human cognitive faculties and saw the highest truths given only in divine revelation, which - with reference to the succession in office ( apostolic succession ) - can only be found in the ( canonized ) scriptures recognized by it and in the fixed confessional formulas prescribed by it . Specifically, the disputes sparked particularly on questions of astrology and magic. From the 4th century AD, the power of the church had consolidated to such an extent that even minor deviations from the “right faith” could be punished with death by fire or the sword. The evidence of the views of these " heretics " were destroyed and almost completely lost, so that well into the 20th century one had to rely largely on the not exactly impartial descriptions of declared opponents such as Irenaeus of Lyon . It was not until 1945 that a collection of Gnostic texts was discovered in Nag Hammadi , Egypt, which had escaped the "purges" and for the first time allowed a comprehensive and unadulterated insight into what we believed to be true or orthodox Christianity. The same applies to the discovery made in 1930 by Medinet Madi , which preserved the oldest known Manichaean original manuscripts (4th century). In the myth of the syncretistic world religion reconstructed from these writings, the stages are described how light came into the world and how it can return to the kingdom of light through the cooperation of man on the same path.

middle Ages

In the Middle Ages , large parts of these ancient teachings fell into oblivion in the Christian cultural area, while they were preserved in the Islamic area and often taken up and in some cases also flowed into Jewish mysticism . In particular, doctrines that implied an individual salvation or referred to religious documents that had not found their way into the biblical canon were excluded from Orthodox Christianity. In addition, however, pagan (“pagan”) religions continued to exist in the Mediterranean region , and in the Middle East, Manichaeism , Zoroastrianism and Islam in particular remained alongside Orthodox Christianity.

On the other hand, within the latter, the newly emerging monasteries - especially those of the Benedictine order founded in 529 - offered space for the cultivation of contemplative mysticism, which now spread to the north. Some writings that appeared in the 5th and 6th centuries were of great importance for medieval mysticism, when Dionysios Areopagita was named, a contemporary of Paul whom he had mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles . This Dionysius represented a strongly Platonic "negative" theology, in which he expressed that God was inaccessible to all conventional knowledge. Only the complete renunciation of all “knowledge” in the conventional sense enables “unity” with God and thus a knowledge that goes beyond all that is knowable. In addition, Dionysius was the first to create a structured hierarchy of angels , i.e. H. the spiritual beings mediating between God and man. It was only about a thousand years later that serious doubts arose as to whether the author of these writings could really be the one Paul mentioned, and today it is considered proven that they could have been written towards the end of the 5th century at the earliest. The author is therefore mostly referred to as the Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita today.

From the 8th century onwards, under the rule of the Moors, who were very tolerant in religious matters, all kinds of Islamic, Jewish and Christian spirituality could develop in peaceful coexistence, among which Islamic Sufism should be mentioned in particular . Plato and other Greek philosophers were also better known from here in western Europe.

The outstanding figure of early medieval mysticism and at the same time the most important philosopher of his epoch was Johannes Scotus Eriugena , who lived in the 9th century and was appointed to the Paris court school by Emperor Charles the Bald . His teaching was strongly influenced by Dionysius Areopagita and Neoplatonism, and he submitted the first usable translations of the works of Dionysius into Latin, which could also develop their effect in the West. A central theme of his teaching was the return of man to God, the “becoming God” (Latin deificatio or Greek théosis ) through heightening of consciousness, in the sense of Neoplatonism. Admittedly, his views were condemned by local synods while he was still alive , and in the 13th century, at the behest of the Pope, all tangible copies of his main work were destroyed.

A movement comparable to the early Christian Gnosis are the Cathars , about whom reports are available from the middle of the 12th century, but whose origin is largely obscure. The main focus of this rapidly expanding spiritual movement was in southern France and northern Italy. It deviated from the Roman Catholic doctrine in essential points and was therefore soon massively opposed. Katherertum was mainly linked to the spirituality of the Gospel of John, while it rejected large parts of the Old Testament. Furthermore, it did not see Christ as a man, but as a heaven-sent Savior. The Cathars saw redemption in the fact that the human soul would return from the material world, which was considered dark, to its home of light. The Cathar community was strictly hierarchical; only the small circle of the "perfected" living in strict asceticism were initiated into their secret doctrine. As a "counter-church", which is very popular in large parts of southern France, it developed into the most important competition of the Roman church in the Middle Ages, until it called for a real crusade , as a result of which Catharism was completely destroyed.

The Jewish Kabbalah appeared as a new mystical secret doctrine in southern France and Spain in the 12th century , which initially gained great importance in Judaism, but later also played an important role outside of it in the history of esotericism. Originally limited to the interpretation of the Holy Scriptures ( Torah ), the Kabbalah soon also developed an independent theological teaching (see Sephiroth ), which was connected with magical elements ( theurgy ). Some Kabbalists (most prominently Abraham Abulafia ) took the view (like the Christian Gnostics) that one can arrive at "absolute" knowledge not only through interpretation of the Torah, but also through direct mystical experience .

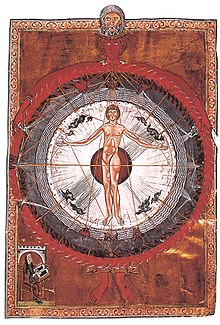

Until the 13th century, there are still essential parts of what would later be called esoteric within official Christianity, including cosmological teachings, thinking in terms of correspondences , imagination and the idea of spiritual transformation. Examples of this are in Germany the mystic Hildegard von Bingen , in France the Platonic school of Chartres ( Bernardus Silvestris , Guillaume de Conches , Alanus ab Insulis ), in Italy the visionary Joachim von Fiore and the Franciscans , in Spain the Neoplatonic school, the Teaching close to Kabbalah by the Mallorcan Ramon Llull and in England the Oxford School (theosophy of light from Robert Grosseteste , alchemy and astrology from Roger Bacon ). Around 1300, however, averroism prevailed in theology , emphasizing rationalism and rejecting the imaginative.

Mysticism in particular experienced a remarkable boom and popularization in the first half of the 14th century, when its representatives switched to the use of the respective vernacular instead of Latin . Most important here were the German Dominicans Meister Eckhart , Johannes Tauler and Heinrich Seuse ; However, there was similar in the Netherlands, England, France, Italy and Spain. With all the diversity of the inner experience described by these mystics and the terms they used, the common goal of the Unio mystica , the mystical union or communion of man with God, was the “birth of God in the soul ”. Medieval mysticism reached a climax in Eckhart's mystical thinking; at the same time, however, it forms the starting point for a new direction in mysticism, which was to have an effect well into the early modern period. For him, “mysticism” did not stand for ecstatic rapture, but for a special way of thinking that goes beyond arguing and reasoning and leads to an immediate grasp of the absolute, even to becoming one with it. Eckhart thus tied in with Johannes Scotus Eriugena, Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita and Neoplatonism. Since he made extensive use of the German language, he became the most powerful exponent of this Platonic tendency within Christian theology, although parts of his teaching were posthumously condemned as heresy and his generally understandable dissemination of difficult theological discussions also met with criticism.

Esoteric practices like magic and astrology were common in the Middle Ages. The magic also belonged invocation ( invocation ) of demons and angels , the existence of which was recognized by the demons as fallen angel in theology. The alchemy became in the 12th century a certain importance, starting with the Arab-Muslim sources in Spain.

Early modern age

During the Renaissance , when people went back to antiquity, esotericism also experienced an upswing. Decisive for this were the rediscovery of important hermetic writings ( Corpus Hermeticum ), the invention of printing with movable metal letters, which opened up a much wider audience, and the effects of the Reformation . Antoine Faivre , the old master of esoteric research, even sees the actual “starting point of what should later be called esoteric” in the 16th century , and therefore regards comparable phenomena in antiquity and in the Middle Ages merely as forerunners of esoteric: “as the The natural sciences were detached from theology and they began to be pursued for their own sake [...], so esotericism was able to establish itself as a separate area, which in the Renaissance increasingly occupied the interface between metaphysics and cosmology ” .

The Corpus Hermeticum , a collection of writings ascribed to the fictional author Hermes Trismegistus , was discovered in Macedonia in 1463 and came into the possession of the patron Cosimo de 'Medici in Florence . These texts seemed to be very old, even older than the writings of Moses and thus the entire Judeo-Christian tradition, and to represent a kind of “primal knowledge” of humanity. Cosimo therefore immediately commissioned a translation into Latin, which appeared in 1471 and caused a sensation. The corpus was seen as an "eternal philosophy" ( Philosophia perennis ), which the Egyptian, Greek, Jewish and Christian religions are based on as a common denominator. Thanks to the printing press it gained widespread use, and by 1641 there were 25 new editions; it has also been translated into various other languages. In the 16th century, however, doubts arose as to the correct dating of these texts, and in 1614 the Geneva Protestant Isaac Casaubon was able to prove that they could only have been written in post-Christian times. But by then they had developed their enormous effect.

The translator of the Corpus Hermeticum , Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), also translated the works of Plato and several Neoplatonists into Latin and wrote his own commentaries and introductions to Platonic philosophy. It was only because of this that the Neo-Platonists became known again after a long oblivion, and the wording of Plato became available. That too had a huge impact. Platonic ideas were brought into position against the Aristotelian theology. One aspect of these controversies was the question of how far human knowledge can go, thereby reviving a major conflict from the times of early Christianity (see above). Some of the Neo-Platonists of the Renaissance even took pantheistic positions, which from the perspective of monotheistic Christianity bordered on heresy .

A third important influence on the esotericism of the Renaissance came from the Kabbalah , in that its methods for interpreting religious documents were also adopted by Christians. The most important representatives of this “ Christian Kabbalah ” were Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494), Johannes Reuchlin (1455–1522) and Guillaume Postel (1510–1581). At the center of Christian-Kabbalistic hermeneutics was the attempt to prove the truth of the Christian message (Christ is the Messiah) on the basis of the original Jewish tradition. This was partly connected with anti-Jewish polemics (the Jews would not understand their own holy scriptures properly), but on the other hand it called on the Inquisition , which culminated in the condemnation of Reuchlin by the Pope in 1520.

In Germany, the Cologne philosopher and theologian Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486–1535) developed an "occult philosophy" ( De occulta philosophia , 1531) from elements of hermetics, Neoplatonism and Kabbalah . In this he distinguished three worlds: the elementary, the heavenly and the divine spheres, to which the human body, soul and spirit correspond. He supplemented the ancient doctrine of the four elements (earth, water, air and fire) with a “fifth essence”, with which he coined the term quintessence . Agrippa attached great importance to magic, which he regarded as the highest science and the most sublime philosophy. Not through science in the conventional sense, which he sharply condemned, but only through “good will” man could approach the divine in mystical ecstasy .

The Neoplatonic division into three parts of man and world and the correspondence of microcosm (man) and macrocosm are also the basis of the medical teaching of Paracelsus (1493–1541). In addition to the four elements, he attached great importance to the three principles of alchemy (Sal, Sulfur and Mercurius). For him, the quintessence of Agrippa corresponds to the Archaeus , an organizing and form-forming force. For Paracelsus, astrology also belonged to medicine, because the human being carries the whole cosmos within himself, diagnosis and therapy require precise knowledge of the astrological equivalents, and the assessment of the course of the disease and the effects of drugs must be made taking into account the planetary movements.

Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) is also one of the important esotericists of the early modern period . He wrote several books on magic, which he considered compatible with empirical natural science ( magia naturalis ), and advocated the doctrine of transmigration of souls . On the other hand, esoteric views seemed to be compatible in many ways with natural science, which in the spirit of Bruno freed itself from church dogmatism. The astronomical "revolutionaries" Nikolaus Kopernikus (1473–1543), Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) and Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) were staunch supporters of astrology, Kepler and Galileo even practiced it, and Isaac Newton (1643–1727) , who is considered the founder of exact science alongside Galileo, also wrote articles on hermetics, alchemy and astrology.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the “classical” Christian theosophy tied in with Martin Luther's demand to only trust in an individual approach to God in addition to the Bible . Its most important representative was Jakob Böhme (1575–1624), a shoemaker who, at the age of 25, had a mystical vision after a difficult life crisis and later wrote about it. According to Böhme, the starting point of all being is the “wrath of God”, which he does not, like the Old Testament, describe as a reaction to human errors, but as a volitional primal principle that exists before creation, even “before time”. Opposite to anger is love, which is seen as the Son of God or as his rebirth. Man can only recognize this “born again God” if he himself is “born again” by fighting with God and being redeemed from this fight by an act of grace and being given absolute knowledge. This theosophical doctrine of Boehme was classified as heretical , and after a first manuscript not intended for publication came into the hands of a pastor, the author was temporarily imprisoned and finally banned from publication. Years later (from 1619), however, he opposed this prohibition, and his writings contributed greatly to the development of a spiritual consciousness based on Protestantism .

In the years 1614 to 1616 some mysterious writings appeared that caused a sensation. Its anonymous authors cited the mythical figure of Christian Rosencreutz , who is said to have lived from 1378 to 1484 and whose legacy they discovered in his grave. The teaching propagated by these first Rosicrucians is a synthesis of various esoteric and natural philosophical traditions with the idea of a “general reformation” of the whole world. Their publication sparked a flurry of approving and disapproving comments; As early as 1620, over 200 related publications had appeared. According to today's knowledge, the supposedly secret order behind it probably only consisted of a few people at the University of Tübingen, including Johann Valentin Andreae (1586–1654).

Enlightenment and romance

An important turning point in the reception of esoteric teachings was marked by Gottfried Arnold's Unparteyic Church and Heretic History, published in 1699/1700 , in which an overview of "alternative" views within Christianity was given for the first time without condemning them as heresies. The Protestant Arnold rehabilitated Gnosis in particular by describing it as a search for "original religiosity ".

In the 18th century a less visionary but more intellectual theosophy developed compared to the “classics” like Jakob Böhme. Its most important representative, Friedrich Christoph Oetinger (1702–1782), was also an important propagator of the Lurian Kabbalah in the German-speaking area. With the first German translation in 1706, the Corpus Hermeticum became more widely known and the subject of scholarly representations. Topics such as vampirism and witchcraft were popular , and figures such as the Count of Saint Germain and Alessandro Cagliostro were very popular. In addition, institutionalized esotericism was established in the form of secret brotherhoods, orders and lodges (especially the Rosicrucians and parts of Freemasonry ).

The renowned Swedish scientist and inventor Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772), who, like Böhme, became a mystic and theosophist due to visions he had in 1744/45, occupies a special position in the field of theosophy . According to Swedenborg's conviction, we live with our unconscious in a spiritual world beyond, in which we consciously “awaken” when we die. As the author of a number of extensive works, he soon advanced to become one of the most influential but also most controversial mystics of the Age of Enlightenment . Followers of his doctrine founded the " New Church " faith community, which still exists today, but he remained a little valued outsider among the theosophists of his time, and his most important critic was none other than Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), who wrote the pamphlet Dreams one to him in 1766 Dedicated to the ghost seer.

During the Enlightenment, to whose most important thinker Kant would advance through his later major works, esotericism had grown into another powerful opposition in addition to the established churches. Because of his understanding of reason and knowledge, even though Kant himself had adhered to the doctrine of migrating souls at a young age, Kant had to reject doctrines such as Swedenborg's, and in this he was soon followed by the great majority of scholars. According to Kant, one cannot prove that Swedenborg's claims about the existence of ghosts and the like are false, but neither can the opposite, and if one were to accept even a single ghost story as true, one would thereby become the entire self-image of the natural sciences to question.

The Freemasons , on the other hand, show that enlightenment and esotericism do not necessarily have to be in opposition to one another , in whom an active advocacy of rational enlightenment and a widespread interest in esotericism coexisted and "enlightenment" was often equated with striving for "higher" knowledge, connected with the esoteric motif of the transformation of the individual. Esoterically oriented orders belonged to many important people in the 18th century, including the Prussian Crown Prince and later King Friedrich Wilhelm II , whose order only existed until his coronation, because from the point of view of the order's leadership it had fulfilled its purpose. Although some other nobles were also important Freemasons, Freemasonry overall played a role in strengthening the emancipating bourgeoisie against the absolutist state.

A considerable amount of esoteric ideas flowed into the natural philosophy and art of German Romanticism . Such was Franz von Baader (1765-1841) at the same time a major natural philosopher and prominent Theosophist this era. In the latter respect he tied strongly to Böhme, albeit in an extremely speculative manner. In romantic poetry, the esoteric influence is particularly evident in Novalis (1772–1801), but also, for example, in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), Justinus Kerner (1786–1862) and several other important poets. Novalis understood nature as a large living whole, with which the human being can cognitively merge in the course of an initiation . He also took up alchemical and Masonic symbols. In terms of music, Mozart's opera The Magic Flute, which was written in a Masonic setting, should be mentioned, in the painting by Philipp Otto Runge .

Modern

With the establishment of modern chemistry in the late 18th century (mainly through Lavoisier's writings 1787/1789) the decline of “operational” alchemy was initiated, which initially did little to affect its popularity, and there was also a “spiritual” alchemy as one special form of gnosis. Also, electricity and magnetism were at this time familiar themes of esoteric discourse, with particularly the Swabian physician Franz Anton Mesmer in his theory of "(1734-1815) animal magnetism excelled". Mesmer linked the old alchemical idea of an invisible fluid flowing through everything with the modern concept of magnetism and the claim that it could be used to cure diseases. After he settled in Paris in 1778, the "magnetic" healing devices he developed conquered the local coffee house scene in particular. His "therapy method" of sitting around such a device in groups, falling into a trance and ecstasy and letting the "magnetism" of healthy people involved flow into him, can be considered a forerunner of the later spiritualistic séances .

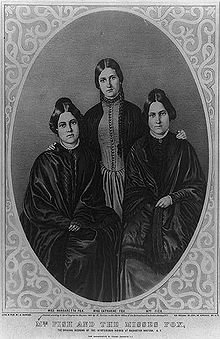

End of the 18th century, the new practice appeared to offset mostly females in a "magnetic sleep" and then to the spiritual world surveys . The aforementioned Justinus Kerner dealt with this in the German-speaking area . A modification of this practice is spiritualism , which originated in 1848 with two sisters in the USA, but which quickly spread to Europe and found millions of followers. Here, too, a person serves as a “ medium ”, and questions are asked which address the spirits of the deceased. Have the spirits respond by moving the table at which the session is taking place. In connection with the idea of reincarnation, a real religion developed from it.

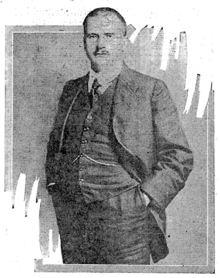

Éliphas Lévi (1810–1875) is considered to be the founder of occultism in the true sense of the word in the second half of the 19th century . Although his works were only "poorly skilful compilations" (Faivre), he was at times the most important esoteric at all. The extensive occult work of Papus (1865–1916) was also influential ; In the German-speaking area, Franz Hartmann (1838–1912) should be mentioned above all . This occultism was a countercurrent against the prevailing belief in science and against the disenchantment of the world by materialism . However, he saw himself as modern (Faivre calls him an answer of modernity to himself) and in general did not reject scientific progress, but tried to integrate it into a broader vision.

A characteristic of modernity , which was shaped by the Enlightenment of the 18th century, but also by the neo-Kantianism of the 19th century, is the increasing separation of material and sacred - transcendent areas of reality. On the one hand, nature and the cosmos are increasingly rationally understood and thus "disenchanted", on the other hand, the transcendent is assigned an extra-worldly level. This can also give rise to the counter-reaction of wanting to sacralize nature, the cosmos and material reality again and thus remove the separation between worldly and extra-worldly spheres. Since the belief in the predictability of all things and the fundamental explicability of the cosmos itself are the result of a development in the history of religion, namely the de-soul of the cosmos already laid down in the Old Testament conception of creation, the modern turning away from this religious tradition can also turn away from belief bring rational science to itself. This can lead to the conviction that neither religion, such as Christianity, nor science have the “true” sovereignty over the world, but that an explanation of the world is only possible with scientific and spiritual interpretation. Various groups that can be assigned to modern esotericism represented exactly this belief.

In a narrower sense, the year 1875 is often seen as the year of birth of modern western esotericism, marked by the foundation of the Theosophical Society (TG) in New York. The initiator and then also the president of this society was Henry Steel Olcott (1832-1907), a renowned lawyer who had long been interested in esoteric topics and was close to the Freemasons . The most important person, however, quickly became Olcott's partner Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891). HPB, as it was later mostly called, was of German-Ukrainian origin and had spent many years traveling in large parts of the world. Since her childhood she had been in media contact with spiritual “masters” in India, from whom she had now (according to a notebook entry before the foundation of the TG) received the “instruction” to found a philosophical-religious society under the direction of Olcott. Olcott also relied on instructions from "masters", which he received in the form of letters. The goals of the TG were formulated as follows: firstly, they should form the core of a universal brotherhood of mankind, secondly, stimulate a comparative synthesis of religious studies, philosophy and natural science, and thirdly, investigate unexplained natural laws and forces hidden in man. The term “theosophical” was apparently taken from a lexicon at short notice.

Shortly after the founding of the TG, Blavatsky set to work on her first bestseller The Unveiled Isis ( Isis Unveiled ), which came out in 1877 and the first edition of which was sold out after ten days. In this and other writings - the major work The Secret Doctrine ( The Secret Doctrine ) was published in 1888 - bundled HPB the esoteric traditions of the modern era and gave them a new form. Of great importance was the connection with Eastern spiritual teachings, in which there had been a great deal of interest since the Romantic era, but which now came to the fore as the purest "primordial evidence" of mankind, which was decisive for the esotericism of the 20th century should shape. Blavatsky himself stated, on the one hand, that she owed her knowledge to a large extent to the almost daily “presence” of a “master” (which a hundred years later would be called “ channeling ”). In the foreword to the Secret Doctrine, however, she claimed that she was only translating and commenting on an ancient and hitherto secret Eastern document (the Book of Dzyan ). Even after the publication of Isis Unveiled , however, critics began to show that the content of this book was almost entirely to be found in other contemporary literature, with most of the books in question being immediately available for HPB in Olcott's library. However, this did not detract from the enormous impact of her work.

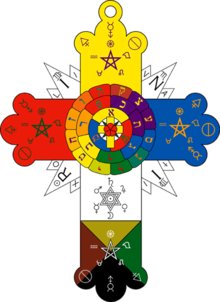

Towards the end of the 19th century, a whole series of new initiatory communities and magical orders emerged in the environment of the Theosophical Society, predominantly in the Masonic and Rosicrucian tradition, including the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn (1888). This order was inspired by the Christian Kabbalah and the Tarot , dealt with Egyptian and other ancient deities, and devoted considerable space to ceremonial magic . Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), who later joined the Ordo Templi Orientis (1901) founded in Vienna and gave it a sex-magical and anti-Christian orientation, stood for the latter . Crowley is considered the most important magician of the 20th century.

In Germany, Franz Hartmann founded a German department of the Theosophical Society in 1886 and a Rosicrucian Order in 1888. Much more important was Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925), who in 1902 became general secretary of the newly founded German section of the TG. Steiner took over a lot from Blavatsky, at least in the first few years, but was himself strongly influenced by the scientific works of Goethe and German philosophers such as Max Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche and finally developed his own Christian-Occidental doctrine that was linked to mysticism , which he later " Anthroposophy ”after the break with the international Theosophical Society represented by Annie Besant . As a representative of a Christian theosophy in Germany in the tradition of Jakob Böhme and Franz von Baader , Leopold Ziegler (1881–1958) should also be mentioned in the 20th century .

The most popular branch of esotericism in the 20th century was undoubtedly astrology . It serves the need to restore the lost unity of man and universe with the help of the principle of correspondence . In addition to the practical application, this can also have a “gnostic” aspect in that one tries to interpret “signs” and develop a holistic language. A similar duality of practice and gnosis is also present in the tarot and in the distinction between ceremonial and initiatic magic .

Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) had an outstanding influence on the development of popular esotericism in recent decades (“ New Age ” ). Jung postulated the existence of universal spiritual symbols, which he called “ archetypes ” and sought to identify them through an analysis of the history of religion and, in particular, the history of alchemy and astrology. In this perspective, the inner transformation of the adept became the central content of esoteric action, so u. a. in "psychological" astrology. This is based on a concept of the soul , as it was already to be found in a similar form in the ancient Neo-Platonists and in Renaissance thinkers such as Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola . In contrast to traditional psychology , which is based on the mechanistic-scientific approach of medicine and regards the talk of a soul as a result of metaphysical , i.e. unscientific speculation, here the soul is elevated to the "true core" of the personality and is downright sacralized , i.e. . H. considered divine by their very nature. Man strives for perfection by immersing himself in his own divinity, which, in contrast to some Eastern teachings , is ascribed to the individual .

Jung's concept of the collective unconscious , which was developed from the theory of archetypes, is also one of the origins of transpersonal psychology , which assumes that there are levels of reality on which the boundaries of the ordinary personality can be exceeded and a common participation in an all-embracing symbolic world is possible . Such ideas combined in the American hippie movement with a great interest in Eastern meditation techniques and psychoactive drugs . The most important theorists of this transpersonal movement are Stanislav Grof and Ken Wilber . Grof experimented with LSD and tried to develop a system of the occurring “transpersonal” states of consciousness.

For communication with transcendent beings in a changed state of consciousness (e.g. in trance ), the term “channeling” was established in the 1970s. The prophecies of Edgar Cayce (1877–1945) became very popular in this area . Other important media were or are Jane Roberts (1929–1984), Helen Schucman (1909–1981) and Shirley MacLaine . The teachings of theosophists such as Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and Alice Bailey are also to be counted here, and similar things can be found in neo- shamanism , in the modern witch movement and in neo-paganism . What they all have in common is the conviction of the existence of other worlds and of the possibility of obtaining information from them that can be useful in this world.

Another central topic of today's esoteric are holistic conceptions of nature, whereby scientific or natural philosophical approaches form the basis for a spiritual practice. One example of this is deep ecology , a biocentric synthesis of ethical, political, biological and spiritual positions directed radically against the prevailing anthropocentrism ( Arne Næss , deep ecology , 1973). Deep ecology regards the entire biosphere as a single, coherent "network", which is not only to be recognized as such , but also to be experienced in a spiritual dimension . Related to this are James Lovelock's Gaia hypothesis , which regards the whole planet earth as an organism, and related concepts by David Bohm , Ilya Prigogine , David Peat , Rupert Sheldrake and Fritjof Capra , which can be summarized as "New Age Science".

In the field of Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism , numerous initiatory societies were founded in the 20th century. The Rosicrucian order AMORC, founded in 1915, had a particularly broad impact . In the German-speaking area, the Anthroposophical Society, with its center in Dornach near Basel, is the most important, which is reinforced by the success of the Waldorf schools that work on an anthroposophical basis . The Theosophical Society fell apart after Blavatsky's death in several groups which are very active in various countries today.

As in Romanticism, esoteric influences in art and literature can also be demonstrated in modern times. This applies, for example, to the architecture of Rudolf Steiner ( Goetheanum ), to the music of Alexander Scriabin , the poems of Andrej Belyi , the dramas of August Strindberg and the literary work of Hermann Hesse , but also to areas of more recent science fiction such as the Star Wars film trilogy by George Lucas . The Theosophical Society also had a significant influence on the visual arts . Examples of artistic design in the service of esotericism are some tarot sheets and the illustrations in some esoteric books. The music of Richard Wagner and the paintings of Arnold Böcklin were not esoterically influenced in the strict sense, but popular objects of esoteric interpretations .

Esotericism as a subject of scientific research

Origins of esoteric research

What is now called Western esotericism was apparently first recognized as an independent and coherent field towards the end of the 17th century. In 1690/1691 Ehregott Daniel Colberg published his polemical work The Platonic-Hermetic Christianity , and in 1699/1700 this was followed by Gottfried Arnold's impartial church and heretic history , in which he defended varieties of Christianity from a Christian-theosophical perspective that had been classified as heretical up until then. This theologically oriented work was followed by a philosophy-oriented one, initially Johann Jakob Brucker's Historia critica Philosophiae (1742–1744), in which various currents were treated that are now attributed to Western esotericism, and finally The Christian Gnosis or the Christian religious philosophy in its historical Development (1835) by Ferdinand Christian Baur , who drew a direct line from ancient Gnosis via Jacob Böhme to German idealism .

In the further course of the 19th century, such topics were largely excluded from scientific discourse, as they were viewed as the products of irrational enthusiasm or classified as pre-scientific (alchemy as proto-chemistry or astrology as proto-astronomy). Instead, occultists such as Éliphas Lévi or Helena Petrovna Blavatsky wrote extensive "histories" of esotericism, in which, as Hanegraaff writes, their own imagination replaced a critical examination of historical facts, which even contributed to the fact that serious scholars avoided this topic. It was not until 1891–1895 that Carl Kiesewetter again presented an important academic study with his history of modern Occultism , followed by Les sources occultes du Romantisme by Auguste Viatte (1927) and Lynn Thorndike's eight-volume History of Magic and Experimental Science (1923–1958). A comprehensive view of western esotericism, which roughly corresponds to the perspective of today's esoteric research, seems to have been the first to develop Will-Erich Peuckert in his Pansophie, published in 1936 - an attempt on the history of white and black magic , which begins with Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and through Paracelsus and Christian theosophy leads to Rosicrucianism.

Hermetics and Modern Science: The Yates Paradigm

In her sensational book Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition , the historian Frances A. Yates tried to prove in 1964 that hermetics , as represented by Pico della Mirandola, Giordano Bruno and John Dee , was an essential element in the foundation of modern science in the Renaissance Played a role and that this science would not have come about without the influence of hermetics. Although the “Yates paradigm” was ultimately unable to establish itself in this strong form in academic circles and Yates' provocative theses mainly met with a response in religious and esoteric literature, it is because of the debates that it triggered as an important “initial spark “Considered for modern esoteric research.

Esotericism as a Form of Thought: The Faivre Paradigm

In 1992, Antoine Faivre put forward the thesis that esotericism can be viewed as a form of thought (French forme de pensée ) that stands in contrast to scientific, mystical, theological or utopian thinking.

Faivre understands esotericism as a certain way of thinking:

- Correspondences : Symbolic or real connections exist between all parts of the visible world and all parts of the invisible world and vice versa. These connections can be recognized, interpreted and used by humans. Two types of correspondence can be distinguished: the constellations found in nature with humans or parts of their psyche or body (as in astrology ) and between nature and revealed scriptures (as in Kabbalah ).

- Living nature : Nature in all its parts is viewed as being essentially alive. Therefore, in addition to material reality, it can also be attributed spiritual and spiritual properties. Recognizing and describing these is particularly important in the Paracelsian tradition.

- Imagination and mediation : There are a number of mediators who can reveal the correspondences (as rituals, spirits, angels, symbolic images). The most important tool for this is the imagination ; it is a kind of "soul organ" with the help of which man can establish a connection to an invisible world. For Faivre, the lack of this characteristic is the essential difference between esotericism and mysticism .

- Experience of transmutation : Transmutation is a term originally derived from alchemy and means the transformation of a part of nature into something else on a qualitatively new level. In alchemy, for example, this would be the transformation of lead into gold. This principle is also generally applied to humans in esotericism and then stands for the so-called “second birth” or the change to the “true human being” in the course of an individual spiritual path of salvation.

Faivre's approach proved to be very fruitful for comparative research, was adopted by many other esoteric researchers and largely replaced the Yates paradigm, but it also met with a wide range of criticism. It was criticized that Faivre based his characterization mainly on investigations of the Hermetism of the Renaissance , natural philosophy , Christian Kabbalah and Protestant theosophy and thus defined the term esoteric so narrowly that he referred to corresponding phenomena in antiquity, in the Middle Ages and in modern and outside of Christian culture (Judaism, Islam, Buddhism) are often no longer applicable. Undoubtedly, however, the Faivre paradigm was instrumental in ensuring that esoteric research was recognized as part of the serious scientific community.

Institutions

A first special chair for the “History of Christian Esotericism” was established in 1965 at the Sorbonne in Paris (renamed in 1979 to “History of esoteric and mystical currents in modern and contemporary Europe”). Antoine Faivre held this chair from 1979 to 2002 , and since 2002 as emeritus alongside Jean-Pierre Brach .

Since 1999 there has been a chair in Amsterdam for the “History of Hermetic Philosophy and Related Currents” ( Wouter J. Hanegraaff ). Third, a center for esoteric research was set up at the University of Exeter (England) ( Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke ; † 2012). In 2006 the Vatican set up a “Chair for Non-Conventional Religions and Spiritual Forms” (Michael Fuß) at the Pontifical Angelicum University in Rome.

The most important German-language specialist journal is Gnostika .

Esotericism and Politics

From the early 19th century onwards, various esoteric currents had a considerable influence on the intellectual justification of democracy and on the development of historical awareness. It was on the one hand a romantic return to the original in rejection of modernity, on the other hand a progressive expectation of the occurrence of predicted events. Examples of the latter are early socialists such as Robert Owen , Pierre Leroux and Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin . Conversely, it can be shown that the persistence of early socialist ideas, especially Saint-Simonism and Fourierism , after 1848 was essential for both the emergence of spiritualism and occultism.

Aleister Crowley was inclined towards Stalinism and Italian fascism . Julius Evola went even further by also turning to National Socialism . While Stalin was relatively tolerant of such phenomena, they were quickly eliminated in Nazi Germany. An esotericist who radically rejected modernity and turned to Islam was René Guénon . Parts of the New Age took up the expectations of earlier occultism.

Objective points and controversies

Attitude of the churches

Some practices that are now classified as esoteric, especially fortune telling and magic , are already sharply condemned in the Tanakh , the holy scriptures of Judaism . In early Christianity, fundamental internal conflicts arose, which led to the exclusion of many so-called "Gnostic" groups from the institutionally strengthening church , which is why their deviating teachings and claims to knowledge are now also esoteric (see chapter "History") .

To this day, the official teaching of the main Christian currents ( Orthodoxy , Catholicism , Protestantism ) clearly opposes any form of "fortune-telling" and magic, such as the Catechism of the Catholic Church :

“ God can reveal the future to his prophets and other saints. The Christian attitude, however, is to trust the future to providence and to abstain from any unhealthy curiosity. [...] All forms of fortune-telling are to be rejected: the use of Satan and demons , necromancy or other acts that are wrongly assumed to 'unveil' the future. Behind horoscopes , astrology , palmistry , interpreting omens and oracles , clairvoyance and questioning a medium hides the will to power over time, history and ultimately over people, as well as the desire to incline the secret powers. This contradicts the loving reverence that we alone owe to God. All practices of magic and sorcery, with which one wants to subjugate secret powers, in order to put them in his service and to gain a supernatural power over others - be it also to give them health - seriously violate the virtue of Worship. "

The Evangelical Church in Germany writes:

“ Esotericism is rejected by the churches because it means occult practices, spiritualism, UFO beliefs and the like. a. m. connects. "

Controversy about the relationship to right-wing extremism

Influenced by Theodor W. Adorno's “Theses Against Occultism” (1951), the notion of an ideological proximity between esotericism and fascism is widespread , especially in German-speaking countries (see right-wing extremism and esotericism ). Adorno saw similarities in a departure from modernity, in irrationality, magical thinking and authoritarian structures. The religious scholars Julian Strube and Arthur Versluis criticize Adorno's theses intolerance, prejudice and generalizations. Versluis even accuses Adorno of having identified victims of National Socialist extermination efforts with the perpetrators ("Integration itself turns out to be an ideology for disintegration in power groups that exterminate one another") and that he uses anti-Semitic thought patterns against them ("shady anti-social", " Decay ").

Among English-speaking Christians, the book was The Hidden Dangers of the Rainbow: The New Age Movement and Our Coming Age of Barbarism (1983, German: The gentle seduction ) of the American lawyer Constance Cumbey attention. Cumbey described the New Age as an organized movement with the aim of establishing a world government and made historical references to the Nazi state . Other authors followed suit.

Since the 1990s, right-wing extremist tendencies in esotericism have been increasingly discussed in the German-speaking area - starting from the left-wing political spectrum . This was largely triggered by the book Fire in the Hearts by the former German Green politician Jutta Ditfurth, first published in 1992 . Ditfurth referred to esotericism across the board as an ideology that was “a foul-smelling stew of stolen elements from all traditional religions that were torn from their social and cultural context” and that had fascist roots. In doing so, she mainly tied in with a study by the Austrian historians Eduard Gugenberger and Roman Schweidlenka who, since the late 1960s, recorded a parallel increase in ecological-alternative, spiritual-esoteric and right-wing extremist tendencies in society and, with reference to the interwar period before a possible " Repetition of History ”warned. Ditfurth wrote in 1992 that the New Age movement (as a synonym for the current esoteric scene) was “not (yet) fascist”, but it also saw a broad relationship: “Esotericism and fascism overlap in the depoliticization of people, the tough ego cult, the elitist leadership and a completely anti-social, anti-humanist and anti-enlightenment orientation. ”Blavatsky's secret doctrine , which Ditfurth (wrongly) assigned to the racist ariosophy ,“ entered ”the thought processes of Nazi leaders, including Adolf Hitler , and at the same time most important root of today's anthroposophy and the New Age scene. "

The British historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke had already presented a fundamental study in 1985 on the role of esoteric ideas in the prehistory of National Socialism , but it was only published in German in 1997 under the title The Occult Roots of National Socialism . In it, Goodrick-Clarke showed that the ariosophy of the early 20th century, whose “standard work” Ditfurth called Blavatsky's Secret Doctrine , had adopted elements of Blavatsky's doctrine, but in relation to the human races (which were still regarded as a natural reality at the time) an opposite one Took a stance: While Blavatsky held out the prospect of a higher development of mankind through the amalgamation of all races and did not want to distinguish between them, the Ariosophs, conversely, propagated strict racial segregation and a racially hierarchical society in order to achieve the same goal. Regarding the influence of ariosophy on the National Socialists, Goodrick-Clarke wrote that Hitler knew it, but largely rejected it.

Regarding the question of a political classification of esotericism, Strube wrote in 2017: “A general classification of esotericism in a certain political spectrum would be misleading. Viewed historically, currents such as Spiritism, Occultism or New Thought were closely intertwined with radical political reform movements - which in the 19th century were mainly to be assigned to socialist, feminist or anarchist directions [...]. The role of the Theosophical Society in the anti-colonial and emancipatory context of South Asia is well known ( Annie Besant, for example, President of the Theosophical Society since 1907, was elected President of the Indian National Congress in 1917 ). However, some elements that were articulated by certain esotericists offered points of contact for racist, nationalist and anti-Semitic ideas. ”The religious scholar Gerald Willms also sees a connection between esotericism and racist-folkish thinking in the opposition to materialism and the emphasis on holistic ( holistic ) Approaches. Esotericism is initially interested in personal spiritual development and is mostly apolitical. There is only a "gray area to the right edge".

Skeptic Movement

Representatives of the skeptic movement express fundamental criticism of any esotericism . The physicist Martin Lambeck claims that esotericism wants to grind the “mechanistic-materialistic” world view of physics, and that physics therefore appears “like a besieged fortress” . According to Lambeck (who apparently relies on a book by Thorwald Dethlefsen ), the “starting point of all esotericism” is the teaching of Hermes Trismegistus ; “ Hermetic philosophy” is synonymous with esotericism. In particular, the principle of analogy formulated classically in the sentence “As above, so below” forms the basis of all esotericism, and the esotericists are convinced that on this basis they can explore the entire world of the micro- and macrocosm. From this it follows, however, according to Lambeck, that from the esoteric point of view "all examinations carried out with telescope and microscope since Galileo have been superfluous" . In addition, the analogization stands "in fundamental contradiction to the method of today's science" . From this and other similar alleged contradictions, Lambeck does not draw the conclusion to reject esotericism. He is concerned with the consistency of the physics teaching building and its claim to be solely responsible for its area. Esotericism makes statements that fall within this area of responsibility, for example that everything in the world is built up from ten original principles (according to Lambeck, a fundamental postulate of esotericism). The existence of such so-called “paraphenomena” must therefore be tested empirically in the sense of Popper's falsificationism .

Commercialization

Many critics, but also some esotericists themselves complain about a "supermarket of spirituality": Different, sometimes contradicting spiritual traditions, which arose over centuries in different cultures of the world, would become a commodity in consumer society , with different trends and fashions quickly alternating ( " Yoga yesterday , Reiki today , Kabbalah tomorrow ” ) and would be deprived of their actual content as a product on the market . This approach is superficial, reduces spirituality to clichés and robs it of its real meaning.

See also

literature

- Egil Asprem and Kennet Granholm (eds.): Contemporary Esotericism . Equinox Publishing, 2013.

- Antoine Faivre : An overview of the esoteric. Secret History of Occidental Thought. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2001, ISBN 3-451-04961-9 .

- Antoine Faivre and Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Eds.): Western Esotericism and the Science of Religion. Peeters, Löwen 1998, ISBN 90-429-0630-8 .

- Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke : The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-19-532099-9 .

- Wouter J. Hanegraaff: Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge 2012.

- Wouter J. Hanegraaff in collaboration with Antoine Faivre, Roelof van den Broek and Jean-Pierre Brach (eds.): Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism. 2 volumes, Brill, Leiden / Boston 2005, ISBN 90-04-14187-1 .

- Kocku von Stuckrad : What is esotericism? Little story of secret knowledge. Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-52173-8 .

- Arthur Versluis: Magic and Mysticism: An Introduction to Western Esotericism. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham (MD) 2007, ISBN 0-7425-5836-3 .

Web links

- Literature on the subject of esotericism in the catalog of the German National Library

- European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lukian, Vitarum auctio 26.

- ↑ For Aristotle's use of language, see Konrad Gaiser : Exoterisch / esoterisch . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 2, Basel 1972, p. 866 f .; Covers there (note 1) and in Henry George Liddell , Robert Scott : A Greek-English Lexicon , 9th edition, Oxford 1996, p. 601.

- ↑ Cicero, De finibus bonorum et malorum 5.12.

- ↑ On the use of the term “esoteric” in this context, see Michael Erler : Platon (= Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Grundriss der Geschichte der Philosophie . Die Philosophie der Antike , Volume 2/2), Basel 2007, pp. 407-409 .

- ↑ Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 5.9.

- ↑ Hippolytos, Refutatio 1,2,4.

- ↑ Compilation and discussion of the evidence in Bartel Leendert van der Waerden : Die Pythagoreer , Zurich and Munich 1979, pp. 64–70. Leonid Zhmud comes to different conclusions than van der Waerden : Science, Philosophy and Religion in Early Pythagoreanism , Berlin 1997, pp. 93-104.

- ↑ Augustine, Epistulae 135.1.

- ↑ The Oxford English Dictionary , 2nd Edition, Volume 5, Oxford 1989, p. 393.

- ^ Trésor de la langue française , Vol. 8, Paris 1980, p. 126.

- ^ Numerous references in Hans Schulz, Otto Basler : German Foreign Dictionary , 2nd Edition, Volume 5, Berlin 2004, pp. 245–248.

- ^ Wouter J. Hanegraaff : Esotericism , in: Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism , Leiden / Boston 2005, p. 337. See also Pierre Riffard: L'Ésotérisme , Paris 1990, pp. 63-137.

- ↑ Antoine Faivre: Esoteric Overview , 2001, p. 13 f.

- ↑ Kocku von Stuckrad : What is esotericism? Little history of secret knowledge , 2004, p. 21

- ↑ Hanegraaff, p. 337 f.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 27-30; Wolfgang Röd: The way of philosophy , Volume I, 2000, p. 47 f. See also Helmut Zander: Geschichte der Seelenwanderung in Europa , 1999, pp. 58 ff., And Jan N. Bremmer : The Rise and Fall of the Afterlife , 2002, pp. 11–26.

- ↑ Stuckrad, p. 29 f .; Röd, pp. 47-49.

- ↑ Röd, pp. 119-125; Stuckrad, p. 26 f.

- ↑ Gerhard Wehr : Gnosis, Grail and Rosenkreuz. Esoteric Christianity from antiquity to today , 2007, pp. 11–18. See also Konrad Gaiser: Exoteric / esoteric . In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 2, Basel 1972 and Plato's 7th letter .

- ↑ Wehr 2007, pp. 39-78; Röd, pp. 273-275; Walter Grundmann: The Gospel according to Mark. Theological hand commentary on the New Testament , Vol. II, 3rd edition, Berlin-Ost 1968, p. 92 (10th edition 1989); Paul, 1 Corinthians; Leopold Ziegler: Tradition , Munich 1949, p. 598; Clemens quoted in Eusebius of Caesarea : Church history VI, 14, 7; Origen: The Gospel According to John I, 8th

- ↑ Röd, pp. 237-261; Stuckrad, p. 27 f. and 243 f. See also Jan Assmann and Theo Sundermeier: The Invention of the Inner Man. Studies on religious anthropology , 1993, and Edmund Runggaldier : Philosophy of Esotericism , 1996, p. 12 f.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 33–41.

- ↑ Röd, pp. 280-284; Gerhard Wehr : The Lexicon of Spirituality , 2006, p. 134 f. See also Christoph Markschies : Die Gnosis , 2nd ed. 2006; Kurt Rudolph : The Gnosis. The essence and history of a religion of late antiquity , 3rd edition 1990.

- ↑ Röd, pp. 281 and 284-288; Stuckrad, pp. 41-47; Wehr 2007, pp. 32–34 and 130–158. See also Elaine Pagels : Temptation through Knowledge. The Gnostic Gospels , 1987; Michael Allen Williams: Rethinking "Gnosticism": An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category , 1996.

- ^ Siegfried G. Richter : The Coptic Egypt. Treasures in the shadow of the pharaohs (with photos by Jo Bischof). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2019, ISBN 978-3-8053-5211-6 , pp. 114–119

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 47–59

- ↑ Wehr 2007, pp. 158–170; Röd, pp. 292-297.

- ↑ Wehr 2007, p. 171.

- ↑ Wehr 2007, pp. 174-176; Röd, pp. 312-314

- ↑ Wehr 2007, pp. 199–208.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 60-77. See also Johann Maier : The Kabbalah. Introduction - Classical Texts - Explanations , 1995; Gershom Scholem : Origin and Beginnings of Kabbalah , 1962.

- ↑ Faivre, pp. 50-52; Wehr 2007, p. 178 f. and 214-220

- ↑ Wehr 2007, p. 243 f .; Röd, p. 384 f.

- ↑ Stuckrad, p. 77 f .; Faivre, p. 53 f.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 72 and 79.

- ↑ Faivre, p. 18 f.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 90-92; Faivre, pp. 59-61. See also Carsten Colpe, Jens Holzhausen: Das Corpus Hermeticum German. Translation, presentation and commentary in three parts , 1997; Martin Mulsow (Ed.): The End of Hermetism: Historical Criticism and New Natural Philosophy in the Late Renaissance , Tübingen 2002.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 81–85 and 88 f.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 113-120; Faivre, pp. 61-63. See also Wilhelm Schmidt-Biggemann (Ed.): Christliche Kabbala , 2003.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 107-110.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 110-113.

- ↑ Stuckrad, p. 122 f. and 143-152. See also Frances A. Yates: Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition , 1964.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 156-159; Faivre, pp. 67-69.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 183-187; Faivre, pp. 69-72. See also Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica (Ed.): Rosenkreuz as a European phenomenon in the 17th century , 2002.

- ↑ Stuckrad, p. 160 f.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 156 and 187-190, Faivre; Pp. 81, 84 and 88. See also Helmut Reinalter (Ed.): Freemasons and Secret Societies in the 18th Century , 1983.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 162-167; Faivre, p. 83.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 165–167.

- ↑ Faivre, pp. 93-98; Stuckrad, p. 190 f.

- ↑ Faivre, pp. 98-107; Stuckrad, pp. 170-173.

- ↑ Faivre, pp. 89-93; Stuckrad, pp. 167-169. See also Heinz Schott (Ed.): Franz Anton Mesmer und die Geschichte des Mesmerismus , 1985.

- ↑ Faivre, p. 109 f.

- ↑ Faivre, pp. 111-113.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 216-218.

- ↑ Michael Bergunder: The pursuit of the unity of science and religion. To understand life in modern esotericism. In: Herms, Eilert (Ed.): Life. Understanding, science, technology. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2005, pp. 559-578.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 197-203.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 197 and 204–207.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 192-194; Faivre, p. 116 f.

- ↑ Faivre, pp. 114-116, 120 and 127 f .; Stuckrad, pp. 209-211

- ↑ Faivre, pp. 124-127.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 219-223.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 233-236.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 229-231.

- ↑ Stuckrad, pp. 231-233

- ↑ Faivre, pp. 139-141; Stuckrad, pp. 207-213.

- ↑ Faivre, p. 121 f. and 144-147; Stuckrad, pp. 224-227.

- ↑ Hanegraaff, p. 338.

- ↑ Hanegraaff, p. 338 f.

- ↑ Stuckrad, p. 11; Faivre, p. 151; Hanegraaff, p. 339.

- ↑ Antoine Faivre: Esoteric Overview. Herder, 2001. p. 33.

- ↑ Stuckrad, p. 14 f .; Hanegraaff, p. 339 f.

- ^ Antoine Faivre , European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism.

- ↑ DIE ZEIT: Learning with Osho .

- ↑ Faivre, p. 150.

- ↑ a b Jean-Pierre Laurant: Politics and Esotericism , in: Wouter J. Hanegraaff (Ed.): Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism , Leiden 2006, pp. 964–966, here p. 965.

- ^ Julian Strube: Socialism, Catholicism and Occultism in France in the 19th Century , De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-047810-5 .

- ↑ Laurant, p. 966.

- ↑ Georges Minois: History of the Future. Oracle - Prophecies - Utopias - Predictions , 1998, p. 29 f .; Ivor S. Davidson: The Birth of the Church , 2003, pp. 163-167; Wehr, pp. 32-34; Stuckrad, pp. 41-47.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church .

- ↑ Faith ABC of the EKD ( Memento of the original from February 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Theodor W. Adorno, Theses Against Occultism . In: Minima Moralia . Reflections from the damaged life. Berlin, Frankfurt am Main 1951. Online in Critique Network - Journal for Critical Theory of Society .

- ^ A b Julian Strube: Esotericism and right-wing extremism . In: Udo Tworuschka (Ed.), Handbuch der Religionen, 55th supplementary volume, Munich: Olzog-Verlag 2018, p. 5 f. ( Online )

- ^ A b Artur Versluis, Theodor Adorno and the "Occult" . In: Arthur Versluis, The New Inqusitions. Heretic-Hunting and the Intellectual Origins of Modern Totalitarianism. Oxford 2006, pp. 95-104.

- ↑ Daren Kemp: New Age: A Guide . Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2004, pp. 134f.

- ↑ Jutta Ditfurth: Fire in the hearts. 1992 (expanded new editions 1994 and 1997), and Relaxed in the barbarism , 1996.

- ↑ Fire in the heart. 1992, p. 190 f.

- ↑ Eduard Gugenberger, Roman Schweidlenka: Mother Earth, Magic and Politics. Between fascism and new society. 2nd edition, Publishing House for Social Criticism, Vienna 1987.

- ↑ a b c Fire in the Hearts , p. 194.

- ↑ Fire in the Hearts , p. 191.

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke: The Occult Roots of National Socialism. Leopold Stocker Verlag, Graz 1997, pp. 10 and 175.