Iamblichos of Chalkis

Iamblichos (* around 240/245 in Chalkis ; † around 320/325) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Neoplatonic direction from Syria .

Life

Chalcis ad Belum (now Qinnesrin), the hometown of Iamblichus, was then part of the Syria Coele province . The name Iamblichos is the Greek form of an originally Semitic ( Syrian and thus Aramaic ) name meaning "He is king" or "May he rule". The philosopher came from an elegant and wealthy family; according to the information of the philosopher Damascius, it was the family of the princes of Emesa (today Homs ). His first teacher was called Anatolios; This was not - as was previously assumed - the Aristotelian Anatolios, who taught in Alexandria and who later became Bishop of Laodikeia ( Latakia ) in Syria, but a Neoplatonist . Iamblichus later joined the Neo-Platonist Porphyrios , who was only a few years his senior , who was a pupil of Plotinus and lived in Italy. Iamblichus was also a Neoplatonist, but did not take over the teaching of Porphyry, but developed his own ideas and criticized the views of Porphyry, sometimes with sharpness. He went into business for himself and founded his own school in his Syrian homeland, most likely in Apamea on the Orontes . Archaeologists believe that they have found his school there.

Among the more prominent among Iamblichus' numerous students were Sopatros of Apamea , who went to Constantinople after the death of the teacher and was executed on the orders of Emperor Constantine the Great , and Aidesios , who took over the management of the school after the death of Iamblichus and later in Pergamon taught.

The most detailed source for the life of Iamblichus is a biography written by Eunapius of Sardis . According to his own statements, Eunapios also relied on oral tradition.

Iamblichus had a son named Ariston who married a student of Plotinus.

Works

All of Iamblichus' works were written in Greek, but they are often referred to by their traditional Latin titles. He wrote an overall presentation of the Pythagorean doctrine consisting of ten books, the original title of which is not known. The first book, About Pythagorean Life , describes the virtues of the Pythagoreans and a Pythagorean educational concept based on the biography of Pythagoras of Samos . The second book, Protreptikos (Appeal) to Philosophy , first provides a general introduction to philosophy and then deals with the specifically Pythagorean method. The third book, The Science of Mathematics in General , describes the philosophical meaning and usefulness of studying mathematics-based subjects. The fourth book, On the Arithmetic Introduction of Nicomachus , explains the introduction to the arithmetic of Nicomachus of Gerasa . The lost books 5, 6, and 7 dealt with the role of Pythagorean number theory in physics, ethics, and theology; extracts from them that the Byzantine scholar Michael Psellos made in the 11th century have survived. Books 8, 9 and 10, which were also lost, represented the remaining subjects (geometry, music, astronomy). Iamblichus took over a wealth of material literally from older literature, and the carelessness with which he proceeded in stringing together these pieces of text has been sharply censured by modern critics. It should be noted, however, that these writings were probably not intended for publication, but for internal use in the school of Iamblichos (in the sense of lecture manuscripts).

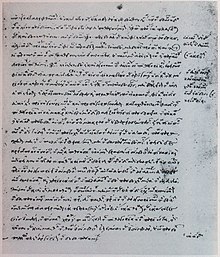

The text About the Mysteries of the Egyptians has survived (the title is not authentic, but comes from the humanist Marsilio Ficino ). In it, Iamblichos replies under the pseudonym "Abammon" to a critical inquiry from Porphyry, which concerns the possibility of connecting with the divine realm through cult activities. Iamblichus also wrote a commentary on the Pythagorean Golden Verses ; the original work is lost, but a surviving Arabic text seems to be a summary of it. All other works by Iamblichus have not survived or have only survived in fragments. These include commentaries on the writings of Plato and Aristotle , a treatise on the soul and one on the gods, and letters.

The earlier Iamblichos attributed font theologoumena arithmeticae ( number theology ) has proven to be false.

Iamblichos contributed significantly to the development of the specialist terminology of late Neoplatonism. His biographer Eunapios criticized his style as unpleasant and a deterrent for the reader. In parts, his tendency to long, confusing sentences makes reading difficult. He was obviously interested in the linguistic aspect of imparting knowledge, because he wrote a treatise on assessing the best expression .

Teaching

Iamblichus was both a Neo-Platonist and a New Pythagorean. He shared the belief, already represented by the Platonist Numenios in the 2nd century AD and later widespread among Neo-Platonists and Neo-Pythagoreans, that there was no difference in content between the teachings of Pythagoras and those of Plato, and he believed that the Pythagorean-Platonic philosophy Expressing truth par excellence. He started from Plotin's concept of emanation as well as from the New Pythagorean numerology of Nicomachus of Gerasa and the “ Chaldean Oracle”. He also assumed that the oracles were in complete agreement with the original teaching of Pythagoras. He saw Pythagoras as a savior who had descended into the material world in order to offer people the salvific good of philosophy.

Iamblichus expanded Plotin's doctrine of the one , the first principle, by doubling the one, because he considered it necessary, between the absolutely transcendent one, which rests in itself and from which nothing can proceed, and the one as the active, creative first principle to distinguish. In the hierarchy below the one, but above the nous , he switched on the duality “limitation” ( péras ) and “the unlimited” ( to ápeiron ) and also assumed an “existing one”, which is the aiōn , eternity. The aiōn establishes the connection to the nous (the intelligible world) below and is the “measure” for them. The nous is also differentiated in Iamblichos. He is the world of the Demiurge , the Creator God, who creates the soul world below and the world that can be perceived by the senses, whereby the “transcendent time” is the link and the “measure” for the lower worlds. With regard to the human soul, Iamblichus rejected the view of Plotinus, who had assumed a permanent communion with the divine realm for the uppermost part of the soul, and justified this with the fact that in this case people would all be constantly happy. In the realm of souls too, he differentiated and adopted natural gradations. He started from an essential difference between the souls of the gods, demons, heroes , humans and animals. Hence, he denied that human souls can incarnate in animal bodies, which Plotinus believed. The Platonic doctrine of the immortality of the soul also referred to the irrational realm of the soul, which later Neo-Platonists like Hierocles of Alexandria regarded as transitory.

The concept of theurgy (cultic action through which man opens up to divine influence) was an innovation that Iamblichos introduced to Neoplatonism and one of its main concerns. While Plotinus recommended the salvation of the soul from its misery in the material world through the striving for spiritual knowledge, Iamblichos also introduced symbolic-ritual ritual acts with which man could approach the divine realm. In his opinion, this theurgic way of salvation was made possible by an encounter of the gods, who gave man theurgy. So what was meant was not an attempt by man to force his redemption by magical means. A redemption of the human soul through its own strength, only through its own virtue and wisdom, Iamblichus considered impossible; therefore, in his view, theurgy was imperative.

In contrast to the dualistic thinking, which Numenios especially represented in Platonism , Iamblichos advocates a strictly monistic world interpretation. For him, as for Numenios, matter is not an independent ungodly principle and as such a source of evil or defects. Unlike Plotinus, he does not fundamentally differentiate between positively valued intelligible matter and physical, sensually perceptible matter as the cause of evil. Rather, it is based on a divine order that continuously structures the entire cosmos from the highest to the lowest level. He therefore assumes a continuity between the spiritual world and the transitory sense objects and thus between intelligible and physical matter, which results from the divine origin of both. He regards the evils as accidental , contrary to nature, deviations from this order that occur on the two lowest levels of existence. Like the other Neoplatonists, he considers matter to be an obstacle that pollutes the incarnated soul and hinders its efforts, but he does not attribute this to a badness of matter itself, but to a wrong attitude of the soul to the material world in which it is lives. Changing this attitude is the goal of his theurgy, which is supposed to divine the soul while it is still in the body.

reception

The theology of Iamblichus made it possible to incorporate the traditional cults of gods into the religious and philosophical world view of Neoplatonism. In doing so, it offered the emperor Julian , who worshiped Iamblichus, a basis for his attempt to renew the non-Christian religion.

Iamblichus influenced the later Neo-Platonists Syrianos , Proklos and Damascius . Proclus often quoted Iamblichus' commentary on Plato's dialogue Timaeus . In the early 6th century Iamblichus' commentaries were still available to the last members of the Platonic Academy in Athens. In the Latin-speaking West, however, it was hardly noticed.

During the Renaissance, the humanist Marsilio Ficino , who valued Iamblichos, made the first Latin translation of the text On the Mysteries of the Egyptians in 1497 .

Text editions and translations

About Pythagorean life

- Michael von Albrecht et al. (Ed.): Jamblich: Pythagoras. Legend - teaching - shaping life . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 3-534-14945-9 (Greek text and German translation of On Pythagorean Life with interpretive essays)

Protreptikos

- Édouard des Places (Ed.): Jamblique: Protreptique . Les Belles Lettres, Paris 1989, ISBN 2-251-00397-5 (critical edition with French translation)

- Otto Schönberger (translator): Iamblichos: Call to Philosophy . Königshausen + Neumann, Würzburg 1984, ISBN 3-88479-143-5 (translation only)

Philosophy of mathematics

- Nicola Festa, Ulrich Klein (ed.): Iamblichi de communi mathematica scientia liber . Teubner, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-519-01443-2 (critical edition)

- Ermenegildo Pistelli, Ulrich Klein (eds.): Iamblichi in Nicomachi arithmeticam introductionem liber . Teubner, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-519-01444-0 (critical edition)

- Eberhard Knobloch , Otto Schönberger (Hrsg.): Iamblichos von Chalkis in Koilesyrien: About the introduction of Nicomachus into arithmetic . Leidorf, Rahden 2012, ISBN 978-3-86757-184-5 (translation with the Greek text from the edition by Pistelli and Klein without the critical apparatus)

About the mysteries of the Egyptians

- Henri Dominique Saffrey, Alain-Philippe Segonds (eds.): Jamblique: Réponse à Porphyre (De mysteriis) . Les Belles Lettres, Paris 2013, ISBN 978-2-251-00580-5 (critical edition with French translation)

- Emma C. Clarke et al. a. (Ed.): Iamblichus: De mysteriis . Brill, Leiden 2004, ISBN 90-04-12720-8 (critical edition - edition by Edouard des Places - with English translation)

- Theodor Hopfner (translator): Iamblichus: About the secret doctrines . Olms, Hildesheim 1987 (reprint of the Leipzig 1922 edition), ISBN 3-487-07947-X (translation only)

Letters

- Daniela Patrizia Taormina, Rosa Maria Piccione (ed.): Giamblico: I frammenti dalle epistole . Bibliopolis, Napoli 2010, ISBN 978-88-7088-600-9 (Greek text, Italian translation, commentary)

- John M. Dillon , Wolfgang Polleichtner (Ed.): Iamblichus of Chalkis: The Letters . Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta 2009, ISBN 978-1-58983-161-2 (Greek text, English translation, commentary)

Other works

- John F. Finamore, John M. Dillon (Eds.): Iamblichus: De anima . Brill, Leiden 2002, ISBN 90-04-12510-8 (critical edition with English translation and commentary)

- John M. Dillon (Ed.): Iamblichi Chalcidensis in Platonis dialogos commentariorum fragmenta . Brill, Leiden 1973, ISBN 90-04-03578-8 (critical edition of the fragments of the Plato Commentaries with English translation and commentary by the editor)

- Hans Daiber (Ed.): Neo-Platonic Pythagorica in Arabic garb . North-Holland, Amsterdam 1995, ISBN 0-444-85784-2 (text of a commentary on the Golden Verses in Arabic, probably a summary of Iamblichos' lost work, with German translation)

- Theologumena arithmeticae (fake)

- Vittorio De Falco, Ulrich Klein (eds.): (Iamblichi) theologumena arithmeticae . Teubner, Stuttgart 1975, ISBN 3-519-01446-7 (critical edition)

- Robin Waterfield (translator): The Theology of Arithmetic. On the Mystical, Mathematical, and Cosmological Symbolism of the First Ten Numbers. Attributed to Iamblichus . Phanes Press, Grand Rapids (Michigan) 1988, ISBN 0-933999-71-2 (English translation)

literature

Overview representations

- John Dillon: Iamblichus of Chalkis (c. 240-325 AD) . In: Rise and decline of the Roman world, Vol. II.36.2, de Gruyter, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-11-010392-3 , pp. 862–909

- John Dillon: Iamblichos de Chalkis . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 3, CNRS Éditions, Paris 2000, ISBN 2-271-05748-5 , pp. 824-836

- John Dillon: Iamblichus of Chalcis and his school. In: Lloyd P. Gerson (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity , Vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-76440-7 , pp. 358-374

- Jan Opsomer, Bettina Bohle, Christoph Horn : Iamblichos and his school. In: Christoph Riedweg et al. (Ed.): Philosophy of the Imperial Era and Late Antiquity (= Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 5/2). Schwabe, Basel 2018, ISBN 978-3-7965-3699-1 , pp. 1349–1395, 1434–1452, here: 1349–1383, 1434–1450

General examinations

- Gerald Bechtle: Iamblichus. Aspects of his philosophy and conception of science . Academia, Sankt Augustin 2006, ISBN 3-89665-390-3

- Thomas Stäcker: The position of theurgy in the teaching of Jamblich . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-631-48926-9

Investigations on individual works

- Friedrich W. Cremer: The Chaldean Oracle and Jamblich de mysteriis. Hain, Meisenheim 1969, ISBN 3-44500645-8

- Beate Nasemann: Theurgy and Philosophy in Jamblich's De mysteriis . Teubner, Stuttgart 1991, ISBN 3-519-07460-5

- Dominic J. O'Meara: Pythagoras Revived. Mathematics and Philosophy in Late Antiquity . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1997, ISBN 0-19-823913-0

- Gregor Staab: Pythagoras in late antiquity. Studies on "De vita Pythagorica" by Iamblichus of Chalkis . Saur, Munich / Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-598-77714-0

Collection of articles

- Henry J. Blumenthal, E. Gillian Clark (Eds.): The Divine Iamblichus, Philosopher and Man of Gods . Bristol Classical Press, London 1993, ISBN 1-85399-324-7

Web links

- Literature by and about Iamblichos von Chalkis in the catalog of the German National Library

- Alexander Wilder (transl.): Theurgia or The Egyptian Mysteries , London / New York 1911

- Riccardo Chiaradonna, Adrien Lecerf: Iamblichus. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Remarks

- ↑ For the dating, see Alan Cameron : The Date of Iamblichus' Birth . In: Hermes 96, 1968, pp. 374-376; John Dillon: Iamblichos de Chalkis . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Vol. 3, Paris 2000, pp. 824-836, here: 826; Gregor Staab: Pythagoras in der Spätantike , Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 145.

- ↑ John Dillon: Jamblich: Life and Works . In: Michael von Albrecht et al. (Ed.): Jamblich: Pythagoras: Legende - Lehr - Lebensgestaltung , Darmstadt 2002, pp. 11–21, here: p. 12 note 5.

- ↑ John Dillon: Jamblich: Life and Works . In: Michael von Albrecht et al. (Hrsg.): Jamblich: Pythagoras: Legend - Doctrine - Lifestyle , Darmstadt 2002, pp. 11-21, here: 14. Dillon changes his earlier view here.

- ^ Gregor Staab: Pythagoras in der Spätantike , Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 148 f .; John Dillon: Jamblich: Life and Works . In: Michael von Albrecht et al. (Ed.): Jamblich: Pythagoras: Legende - Lehr - Lebensgestaltung , Darmstadt 2002, pp. 11–21, here: 15 f .; Daniela Patrizia Taormina: Jamblique critique de Plotin et de Porphyre , Paris 1999, pp. 7 ff., 159 ff.

- ↑ Janine and Jean-Charles Balty : Julien et Apamée . In: Dialogues d'histoire ancienne 1, 1974, pp. 267-304.

- ↑ Gregor Staab: Pythagoras in der Spätantike , Munich / Leipzig 2002, pp. 195–201.

- ^ Gregor Staab: Pythagoras in der Spätantike , Munich / Leipzig 2002, pp. 177–182.

- ^ Gregor Staab: Pythagoras in der Spätantike , Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 194, note 467.

- ^ Hugo Rabe (ed.): Syriani in Hermogenem commentaria , Bd. 1, Leipzig 1892, p. 9 lines 10 f.

- ↑ John Dillon: Iamblichus of Chalkis (c. 240-325 AD) . In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World , Vol. II.36.2, Berlin 1987, pp. 862–909, here: 880–887.

- ↑ John Dillon: Iamblichus of Chalkis (c. 240-325 AD) . In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World , Vol. II.36.2, Berlin 1987, pp. 862–909, here: 885–891.

- ↑ John Dillon: Iamblichus of Chalkis (c. 240-325 AD) . In: Rise and Decline of the Roman World , Vol. II.36.2, Berlin 1987, pp. 862–909, here: 890–898.

- ^ Gregor Staab: Pythagoras in der Spätantike , Munich / Leipzig 2002, pp. 177–182.

- ↑ Gregory Shaw: Theurgy and the Soul. The Neoplatonism of Iamblichus , University Park (PA) 1995, pp. 23-69.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Iamblichos of Chalkis |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Iamblichos; Iamblich; Iambical; Iamblichus; Iamblichus; Iamblichos |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Greek philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | at 240 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Chalkis |

| DATE OF DEATH | at 320 or at 325 |