Gottfried Arnold (theologian)

Gottfried Arnold (born September 5, 1666 in Annaberg ; † May 30, 1714 in Perleberg ), pseudonym: Christophorus Irenaeus , was a German pietistic theologian who is best known as the author of the Unparty Church and heretic history , which includes the story of the Christian Church as a history of decline. From the point of view of the history of his impact, he was the most important representative of radical pietism .

Life

1666 to 1699

Childhood, studies and private tutoring

Gottfried Arnold was the son of the Preceptor (Latin school teacher) from Annaberg. He was born on September 5, 1666 and baptized on September 6 of the same year. He attended grammar school in Gera and, after completing his basic studies in artes liberales, studied theology in Wittenberg , which his father supported. Wittenberg was a refuge of the Lutheran late orthodoxy . Arnold later refused this. According to his own statement, he was persuaded to become a master's degree in 1686; his graduation to the Magister artium was then on April 28, 1687 in Wittenberg.

His interest in pietism was awakened by the writings of Philipp Jacob Spener . From 1688 until the end of his life he was in contact with Spener by letter. Spener persuaded Arnold to go to Frankfurt am Main and found him positions as private tutor in Dresden (1689 to 1693) and Quedlinburg (1693 to 1696). There Arnold came under the influence of mystical-spiritualistic piety, including their criticism of the church. He renounced the assumption of a parish office and the marriage and devoted himself entirely to theological writing.

Between 1696 and 1699 Arnold developed into a radical pietist. Until 1696 he was still of the opinion that he could live a true Christianity within the church, which can be seen in the first edition of the Homilies of Macarius. In 1699 at the latest in the dedication poem for the new edition of these Macarios homilies, radical Pietist traits became clear. Arnold's radicalization can be identified in four aspects:

- Contacts to the Quedlinburg Pietist milieu

- the view of early Christianity as a standard (first love)

- Confrontation with Macarios

- Graduated from the professorship in Giessen

Professorship in Giessen

In 1697, after the great success of his work The First Love of the Congregations of Jesus Christ , Arnold was appointed professor of history at the Pietist University of Gießen . This appointment goes back to Landgrave Ernst Ludwig von Hessen-Darmstadt, who announced his decision to hire Arnold on March 24, 1696. Arnold saw the fact that the Landgrave had appointed him regardless of Arnold's own ambitions as a hint from God, but later as a wrong decision. But how was the Landgrave even made aware of Arnold and his work? For this, the pietistic Giessen professors Johann Christoph Bilefeld, Johann Heinrich May and Johann Reinhard Hedinger come into play, who at least had to approve this decision with regard to their like-minded comrades, if they were not even involved in it. This is supported not least by the fact that the Countess Dorothea Charlotte was open to the concerns of the Pietists. Arnold himself, according to his frank confession, first refused the call, but then allowed himself to be persuaded by other people and their arguments.

Although the course catalog of April 24, 1697 announced Arnold for the summer semester, he did not take up his post until the winter semester. The first entry into "the Hessian Lands" is dated June 12, 1697 , according to the preface to the Divine Sparkles of Love . In his résumé, Johann Konrad Dippel describes an encounter with Arnold and his companions who came to Giessen from Saxony. The companions are M. Johannes Christian Lange and Johannes Andreas Schilling, whose matriculation took place on August 23, 1697, which also indicates the time in which Arnold relocated to Gießen (probably the second entry into Hessen-Darmstadt) around the beginning of September to take office.

On September 1, 1697, Arnold signed the Religious Reverse, which obliged him to accept certain writings (Confessio Augustana invariata, the Apology, the Wittenberg Agreement, the Schmalkaldic Articles and Luther's Catechisms, but not the Formula of the Concord). In addition, signatories were required to report deviations from the teachings of these scriptures. Before the inaugural lecture, Arnold was at the public reading of the above-mentioned commitment in the university senate, which was followed by the oath of the sovereign and the signing of university laws.

On September 2, Arnold gave his inaugural lecture De corrupto historiarum studio .

On November 20, 1697 he was with the Landgravine for the first time, who wrote in a letter to Bilefeld that Arnold had convinced her and that she was positive about him.

At the end of March 1698 Arnold left Gießen and resigned from his professorship. Landgrave Ernst Ludwig received the request for dismissal on May 10, 1698. Arnold justified his resignation on May 23, 1698 to his former colleague Professor Johann Heinrich May.

On May 18, 1698, Arnold visited the radical pietist Johann Wilhelm Petersen in Niederndodeleben.

On June 10, 1698 at the latest, the frank confession must have been available (because the publisher's foreword is dated to this day) in which Arnold publicly justified his decision: repelled by the glorious rationality of academic life , he left the university after his first semester again. He wrote to his colleague from Giessen, Johann Heinrich May , that the abomination of desolation (Dan. 9.27; Mk. 13.14) had reached such an extent that only the exodus from Babel remained the only consequence. Spener wrote a letter about this work on November 28, 1698. On November 29, Arnold responded to criticism of his frank confession . In summary, at least three motives can be identified that moved Arnold to resign from his professorship:

- the finding that even at a pietistic university there is conflict

- Turning away from research on church history, which he himself perceives as a kind of waste of time (from his point of view he should have used the time for God's glory)

- the anguish of the heart that “the tender life of Christ in me greatly diminished”, that is, to deviate from the right path of faith

In addition, Konrad Dippel was physically threatened and attacked and Arnold could not know whether it would be similar to himself.

Arnold returned to Quedlinburg, where his main work Unparteyische Kirchen- und Ketzer-Historie appeared in 1699 , in which he took the view that Christian truth was betrayed by the main church and was to be found among those persecuted as heretics by it .

1700 to 1714

Because of the Pietism dispute in Quedlinburg, it became difficult for Arnold to continue living there. The separatist edict of the abbess of the Quedlinburg monastery is dated July 31, 1700: failure to attend church services, confession and communion is threatened with penalties. On December 27, 1700, on October 14, 1700, around November 20, 1700 and on December 3, 1700, Sprögel was ordered to expel Arnold from his house under threat of a fine. The pastors also rush against Arnold from their pulpits. In “The Right Way” (a collection of three sermons from 1700) Arnold defends himself against the accusations by pointing out that he never deviated from the Word of God. In addition, he had reported opinions of heretics in the UKKH, but these were not necessarily his own.

However, the Prussian elector sided with Arnold in a letter of protection dated October 23, 1700, in which he pointed out that Arnold was not subject to any accusations from the competent jurisdiction (foro competente). On November 1st, Arnold anticipated his deportation because he left Quedlinburg for a short time before the letter of protection arrived. After the letter of protection arrives, Arnold returns to Quedlinburg. On November 5th, von Stammer organized military protection for him in order to assert the interests of the elector against the abbess. A royal commission - consisting of propietist representatives - with a protective mandate for Arnold is set up to bring peace to the cause and to enable Arnold a job elsewhere (Allstedt). Arnold has problems hearing confession and passing the sacrament indiscriminately. Hence the position of the castle preacher with the Duchess Sophie Charlotte von Sachsen-Eisenach in Allstedt. The problems are that, on the one hand, this position also implies an oath of confession and, on the other hand, Arnold was not married. The recently widowed, 30-year-old duchess suggested that Arnold (who was also unmarried at the time), who was only five years her senior, be married in order not to let any rumors arise.

In 1701, Arnold caused considerable irritation among his radical-pietist like-minded comrades: he gave up the celibacy praised in his writing about Sophia and on September 5th married Anna Maria Sprögel, the daughter of the advertising superintendent Johann Heinrich Sprögel , whereupon the spiritualist Johann Georg Gichtel and whose followers break off contact with Arnold. Gichtel initially hopes that Arnold will lead a "sibling marriage" with his wife (a marriage of siblings in faith who live in sexual abstinence). But even this last hope is disappointed at the latest in 1704 with the birth of Arnold's daughter (Sophia Gottfreda).

In addition, he became the priest of the palace in Allstedt in January 1702 , so he accepted an official ecclesiastical office, which is not a classic parish pastoral office, but a position as personal pastor for Duchess Sophie Charlotte - so he did not have to distribute the Lord's Supper indiscriminately. But he continued to insist on radical positions. So he refused to take the oath on the concord formula , whereupon the Orthodox pastors of Eisenach turned against him. Although King Friedrich I campaigned for Arnold to take the oath, Duke J.-W. von Sachsen-Eisenach on this oath so that no precedent is set (letter of September 20, 1701 to the king). Arnold never gave up his fundamental positions, even if he modified them and moderated his extreme views after 1701.

The pietistic nobility of officials of the Berlin court and even Friedrich I , who had appointed Arnold royal historiographer in 1702 , relied on him so that Arnold would enjoy the protection of a Prussian official. From 1702 to 1704 the dispute over Arnold's oath rests, but in September 1704 Arnold is given an ultimatum to leave Allstedt. Despite the support of the king, Arnold had to give up his post in Allstedt in 1705 and took over the office of pastor and superintendent in Werben - according to Sprögel's proposal, who is his father-in-law and predecessor in this position. The advantage of advertising is that Arnold does not have to take an oath in the area of Prussia because he is subordinate to King Friedrich I , who has supported him for a long time. Arnold adjusts his theological stance to the extent that he is now ready to take on a parish pastor, which he does in his work The Spiritual Figure of a Protestant Teacher (published in Halle in 1704).

From 1707 he held these offices in Perleberg . In addition to the church work, he continued his literary work, which shows a strong continuity of his (radical-pietistic) theological thinking.

Arnold suffered a fit of weakness in the pulpit during a funeral sermon on May 21, 1714. On May 30, 1714, Arnold, who had been weakened by scurvy since 1713 , died a few days after recruiting Friedrich Wilhelm I stormed his Pentecost service on May 20 and young men attended Had torn the Lord's Supper from the altar to force them into military service.

“Breaks” and classification in radical pietism

Classically, three "breaks" are assumed in Arnold's life:

- Conversion from Orthodox Lutheranism to Pietism (Dresden period)

- Turning away from the world and the church to radical spiritualism and mystical separatism (Quedlinburg and Giessen times)

- Marriage and return to church pastoral office (1701–1702)

Despite the assumed breaks, there are at least three aspects that represent the continuity of his inner beliefs:

- Characterized by mystical individualism

- The church's idea of decay from the UKKH

- Distance to the constituted church: declaration of the external organization as adiaphora, refusal to take the oath on the formula of concord, refusal to accept confession

Arnold was and remained a radical pietist, even in the later years, because he still fulfilled radical pietist criteria even though he was active as a pastor in the church:

- Church criticism of all "partisan" (that is, divided) churches

- Overemphasis on rebirth over justification

- conversion

- emotional union with God

- Love as the core of the gospel

- pious life according to early Christian standards

- Freedom from theological, ecclesiastical and political constraints

- Apocatastasis ideas

He only chose a middle course in the following two points:

- Separation from the world and from the external church system

- Sexual hostility

He has chosen marriage and an ecclesiastical office, although there were previously more radical phases in which he had rejected these avenues.

plant

overview

Arnold searched for the roots of pure faith , which he saw particularly realized in early Christianity, about which he began to publish. In 1696 he translated and published the 50 homilies in German for the first time , which were handed down under the name of the Egyptian desert monk Makarios and which propagated a mystical - ascetic Christianity. In that year, his first major work, The First Love of the Commons of Jesus Christ , was published, an alternative to William Caves ' Primitive Christianity (1673). While Cave saw the Anglican Church with its episcopal constitution, its official priesthood, rite, festival calendar and its church buildings in the continuity of early Christianity, Arnold saw in early Christianity a contrast image to the church of his time with sincere piety of the heart and general priesthood without dogma, without clerical hierarchy, without established cult and without a church building. Even in this writing, Arnold contrasts the Church of his present with primitive Christianity as an ideal, a pure community gifted by the Holy Spirit and ready to be martyred , which was corrupted by the Constantinian change and the hierarchical state church with its compulsion to dogma and regulated cult.

In 1698 Arnold published 169 poems and songs under the title Divine Love Sparks . Borne by mystical piety, these poems encourage turning away from the world and listening to the inner word of God, which leads to spiritual rebirth and to being permeated by God. This work also includes Babels Grab-Lied , a testimony to extreme pietistic church criticism, which calls for a storm on the secular church and presents the reform of their churches propagated by the church Pietists as hopeless:

- 1. The guardian council / which God has ordered / speaks the sentence / already about Babels wounds, / no doctor or herb was found for them, / so desperately evil be the damage / which Babylon has.

- 3. She infects / the doctor who touches her / and leaves plagues sticking to him for drinking money, / who still wants to keep her alive, / and mends her. So that you can clearly feel / who is touching them.

- 10. That is why her nest storms, / in which she has become proud! / Smash your children on the stones! / Nobody should weep the brood of snakes. Give the rest to their den, the place of iniquity, / and storm their nest.

With his mystical poetry, Arnold is considered the most influential poet of early Pietism. His two songs O breakthrough of all ties (EG 388) and So you lead quite blissfully, Lord, yours found their way into almost all evangelical hymn books. Johann Sebastian Bach did not set the song Arnold's Vergiss mein to music (BWV 504 and 505).

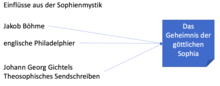

Arnold's most important work is the Unparty Church and Heretic History (see below). In 1700 the book The Secret of the Divine Sophia followed , which follows on from Jakob Böhme and depicts the union of the true believer with the personified wisdom in erotic images, especially the Song of Songs.

"The First Love" (1696)

Influences and impact history

One of the most important influences is Professor Conrad Samuel Schurzfleisch, who gave Arnold the methodological tools and a profound knowledge of sources. Spener should also be mentioned, who in his work Pia Desideria (1675) already advocates the idea of exemplary primitive Christianity, which contains many examples of praxis pietatis (faith that is concretely active and shows itself in life). The examples mentioned by Spener also appear in Arnold's First Love . Arnold himself refers explicitly to William Cave: First Love should be a kind of explanation and at the same time can be understood as an alternative. On the one hand, both have an interest in early Christianity and give it a normative character; on the other hand, Arnold started decay earlier as a cave, who saw legitimacy in the 4th century for the current shape and office structure of the Anglican Church, which Arnold criticized.

The history of the impact can first be shown well by the radical pietist church critics, who find their key witnesses in Arnold. Philadelphian circles in the Werra region in Lower Hesse also delve into First Love , which can be exemplified by Hochmann von Hochenau and the Schwarzenau new baptists. Spener values Arnold's work so highly that he has it read publicly in Berlin after afternoon services. In addition, the beginnings of the Moravian Brethren were shaped by writing, even if Zinzendorf was particularly criticized from the 1740s. In the Wittenberg orthodoxy, which Arnold does not actually exclude from decay, at least one reviewer in the Innocent News admits that the script is suitable for preachers. In the Enlightenment, the book is valued at most as edification literature, but it cannot meet the new methodological requirements, as Baumgarten notes in the foreword to the sixth edition in 1740.

preface

In the preface Arnold makes it clear that the development of the church is a history of decline. The closer you get to the time of the origin, the purer the teaching and actions of Jesus and his apostles can still be found in the church. The first 300 years seem particularly suitable for this, from the Constantinian Turn onwards things went steadily downhill (XI.). Unlike his role model Cave, Arnold would like to write an impartial church history, which also explains Cave's work (VII.). Arnold accuses Cave of primarily looking out for what the current church structures justify in the first 400 years (IIX.). He, on the other hand, would like the readers to free themselves from the present and enter the Old Church as if on a kind of walk (IV.). Arnold also accuses Cave of using too few Bible passages in his argument (IX.).

The advantage of preoccupation with early Christianity is that all the denominations present at the time secretly agreed that the old church should be seen as a model. If the church were to be restored to the way it was then, the divisions between the churches could be overcome. On this point Arnold agrees with Conradus Horneius, whom he acknowledges positively with a quote (I.)

The words and deeds of Jesus and the apostles serve not only as models, but also as God's rules to be followed - their behavior should be mirrored. What Arnold finds particularly exemplary in the old church is that there were less external things, more internal things, fewer ceremonies and more fear of God (II.). True knowledge and thus also understanding of Arnold's statements are reserved for those who have enlightened eyes of the heart that arise through fear of God (III.). Arnold renounces Latin in order to give minors access to church history, in which a lot of Latin is already available (XII.).

Of man's true conversion

In the first chapter of the first book ( From the First Christians Duty and Testimony to God ) Arnold addresses conversion because Jesus and the apostles already made conversion the basis of Christianity. Human nature is so corrupted that it is inherently unsuitable for the kingdom of God. Turning away from oneself and the world is therefore necessary for turning to God. Sin is more often compared to a serious illness that clouds the mind and spirit. The law serves the knowledge of sin (Arnold also refers to Rom 7,7; 3,20). The conversion is described by light metaphors. The fruit of enlightenment includes knowledge of sin and punishment, whereby God's goodness leads on to true repentance. God gave a willing spirit to those who wanted to obey the doctrine, so that they humble themselves. Feeling the divine anger leads to the smashing of the haughty heart. Jesus himself had only promised consolation to those who suffered; those who weep for their old sins because of their conscience. God's Spirit causes hatred of sins. Tears and other effects of sadness serve as a differentiator between true repentance and "hypocritical repentance." The burden of sin was so heavy that it was confessed not only to God but also to men. Instead of just vengeance, God reacts by accepting a blessed confession of repentant conscience. Repentance should not only be carried out in parts, but with all of the heart, so that no sin remains. The people, however, were not proud of their conversion, but were grateful to God for his grace which drew them to him. The change brought about by the mind relates to the whole mind, which is given a completely new direction. The righteous were not allowed to live unholy because those raised from death could no longer remain dead. For whoever has been torn out of his condition by the discipline of God has to prove himself worthy. One of the fruits of penance is letting go of vices so that B. become chaste of fornicators. All souls need this change and renewal. The first Christians not only talked like that, but there are many examples that they actually lived so exemplary. People are not capable of doing this on their own, but it was God's grace through which conversion and holy life was given to praise the glory of God.

"Impartial Church and Heretic History" (UKKH, 1699/1700)

content

General

In his history, Arnold takes up the anti-Roman idea of decay of the Reformation view of history and uses it to interpret the entire history of the church. The decline of Christianity began soon after the times of the apostles and was increased by Constantine . Briefly interrupted by the early days of the Reformation , the decline also affects the Protestant churches.

The inferior institutional Christianity, which is particularly visible in the arrogant exercise of power and opinionated dogma, is opposed to the invisible Church of the Spirit, which is scattered among all peoples and churches, which emerged from the earthly quiets in the country ( Psalm 35:20), to which Arnold expressly referred to the Church as heretics persecuted deviants from the official doctrine counted. Heretical teachings like that of Anna Vetter are also presented in full. The monumental work ends in 1688, to which Arnold apparently linked eschatological expectations. It is also eschatological that Arnold not only differentiates between enlightened / awakened and other Christians, but also sees the decline of Reformation Protestantism and the armed conflicts of his presence as a sign of the times, more precisely the end times. These signs urge repentance.

The annotation apparatus contains approaches to increasing scientific knowledge in historiography. This contrasts with the mystical-spiritualistic perspective, which renounces causal interpretations inherent in the world.

The fact that this church history is "impartial" from Arnold's own point of view does not mean that it is neutral, but that it is at a distance from the religious parties. It is a spiritualistic criticism of the church that assumes that institutionalization misses the true essence of Christianity, which can only exist in the invisible church. Not only does he deny Christianity, but also his own Lutheran church, that it is truly a church by calling it the “so-called church”. It is a de-institutionalized, personalized historical exhibition that consistently breaks away from dogmas and instead focuses on beliefs and practice.

Evaluation of the Reformation

Unlike the reformers, Arnold sees the decline not only beginning with the papacy (for Luther approx. From 607 with the pontificate of Boniface III), but even earlier. Like Spener and his teacher Johann Conrad Dannhauer, Arnold sees primitive Christianity as the model for evaluating developments in church history. The decisive criterion is orthopraxy.

Arnold is particularly interested in the Reformation: the Reformation takes up a disproportionately large part of the presentation, which can be explained not only by the fact that it was not so long ago, but also by the fact that the Reformation comes close to early Christianity from Arnold's point of view. He even honors her with the fact that the first love was still heated and was well fueled by the fire of the tribulation.

“Now it is true that right in the first years of the Reformation there was a great movement and change of hearts in countless people, both in Saxony and other places, as well as in Switzerland, since Zwingli taught, although many of them still was first love, which was not only vigorous and heated by herself, but also splendidly swept and entertained by the fire of tribulation. But that changed soon after the peace and security that had occurred, no different from what happened in the first church. "

Arnold can only determine this for the early Reformation in the first seven years. Although Luther initially had a high regard for God's word, the bloom comes to an end through Luther's break with Karlstadt.

“In the meantime this is certain that Luther himself in the beginning, and before the contradiction and disputes with Carlstadt and others came about, the written word of God was highly respected and used, but also the [...] power of the spirit and the Enjoyed enlightenment. "

Arnold pays tribute to Luther's calling. For Arnold, the vocatio interna in the sense of a mystical spiritualism is more important than the vocatio externa (which was particularly valued in Lutheran orthodoxy) . The early Luther represented enlightenment better than the later. Arnold praises the early Luther for his honesty, humility, prayer, and frank demeanor.

“All in all, experience also teaches him that people, especially teachers, are never better off than when they are under the cross and persecution, and on top of that know no protection or consolation from people. [...] But as soon as it notices a visible protection and consolation, it soon wants to go upstairs [...] and begins to rule over others, but to make itself great. [...] So no one should be surprised if some of them, insofar as they were also people, that is, frail, are perceived after their blissful state under the cross afterwards with protection and elevation. "

As the Reformation established itself and Luther's personal threats diminished, according to Arnold, like Saul from the Bible, Luther lost the Spirit of God. Humility and sanctification would give way to the vehemence of theological debates of a self-centered professor. Luther's marriage is also criticized by referring to his earlier rejection of marriage. From Arnold's point of view, the bloom of the Reformation ended in 1525, not least because of the internal Reformation disputes and Luther's marriage.

Arnold criticizes the confessions as useless instruments for the compulsion of conscience. The teaching has changed, but not the hearts. Therefore, the positive trends could not have prevailed. Instead, the negative aspects predominate, such as the violent repression against Catholic churches and monasteries. This exemplarily shows that wrong motives played a role in the separation from the papacy. Overall, the radical Reformation is presented more positively, not least because it had to endure persecution: enthusiasts and Anabaptists get a lot of space in the presentation.

Influences and impact history

Arnold's writing is shaped by Christian Thomasius, which can be exemplified by the following views and characteristics that both share:

- Church history as the history of wisdom, the history of philosophy as the history of folly

- sharp separation between theology (scriptural revelation) and philosophy (reason)

- Denial of Aristotelianism in theology

- Use of the German language in science

- denominational tolerance

- Front line against orthodox hereticization

The history caused a sensation and sparked angry protests of the church orthodoxy; a series of anti-Arnold tracts appeared. Even Spener largely disapproved of the book, while Christian Thomasius spoke of the best and most useful book according to the Scriptures . With its claim to impartial source study and its tendency to criticize the church and dogma, as well as the sustained emphasis on the subjective in religion and ecumenical tolerance, it forms an important link in the transition from denominational to scientific church history against the background of the early Enlightenment .

Arnold's main work has demonstrably had an impact on the history of ideas, especially on theology (including Christoph Matthäus Pfaff and Johann Salomo Semler ), but also on the thinking of such diverse personalities as Frederick the Great , Gotthold Ephraim Lessing , Johann Gottfried Herders , Friedrich Schleiermacher and Johann Wolfgang Goethes , who wrote about Arnold:

“I experienced a great influence from an important book that got into my hands, it was Arnold's“ Church and Heretic History ”. This man is not a mere reflective historian, but at the same time pious and sentimental. His attitudes were very much in line with mine, and what particularly annoyed me about his work was that I received a more advantageous term from some heretics who had hitherto been presented to me as mad or godless. "

In Pietism, where Arnold's view of the decline of the original Christian idea as a leitmotif of church history lives on, its aftermath is particularly evident in Johann Konrad Dippel and Gerhard Tersteegen and extends to Johann Heinrich Jung-Stilling and the revival movement of the 19th century ( August Neander ) . The mystical-spiritualistic interpretation of history (turning away from institution, teaching, rite; turning to inwardness, piety of the heart and lifestyle) and the biographical traits connect Arnold's work with the history of the reborn (from 1698) by Johann Henrich Reitz .

One of the most important critics is Ernst Salomon Cyprian , who accuses Arnold of separatism. Arnold's declaration of common sectarianism, going to church and the Lord's Supper (1700) is a reaction to Cyprian's accusations, which is not a defense, but rather defines Arnold's position.

Writings on marriage (1700 + 1702)

Arnold has published two works that deal primarily with marriage and celibacy:

- The secret of the divine Sophia (Leipzig 1700) (original: The / Secret / The / Divine / SOPHIA / or / Weissheit / Described and sung / by / Gottfried Arnold [...]).

- The conjugal and unmarried life (Frankfurt 1702) (original: The / Eheliche / and / Unmarried / Life / of the first Christians / according to their own testimonies / and examples / described / by / Gottfried Arnold)

Between the two works is the marriage of Gottfried and Anna Maria Arnold (née Sprögel) on September 5, 1701. One of Jakob Boehme's most important students, namely Johann Georg Gichtel, was originally on the same line as Gottfried Arnold's Sophia . However, he compares the marriage with Samson, who was sneaked by Delilah and robbed of his strength. With this he expresses that Arnold has lost his effectiveness. At least this is true for radical pietist circles who now see in him an apostate who does not keep in his life what he usually writes in the scriptures. You see his marriage as a contradiction to his Sophia . In addition, Gichtel accuses him of having no real, deep experiences with the divine Sophia. In this context, one can classify the emergence of his marriage memorandum 1702: Accordingly, the script is a kind of critical examination of Gichtel's views and a defense that legitimizes the step of the marriage. Even if the marriage script claims a church-historical accent in the title, it must be stated that no primarily historical interest can be found, but - similar to First Love - early Christianity is portrayed as the setting for Arnold's ideals.

| The secret of the divine Sophia | The conjugal and unmarried life | |

|---|---|---|

| Matches | The human being, originally created as imago Dei , was androgynous and in a first case lost the unity with Sophia and thus his feminine characteristics, in a second case Eve gave him a companion for "animal" reproduction. By abstaining from sexual ties, a reunification with Sophia can be achieved. | There is still a high esteem for celibacy, chastity, purification / purity and celibacy in early Christianity. The anthropology of the androgynous original state is not given up either (“male virgin” / “virgin man”). Arnold sticks to the negative evaluation of sexuality as a sign of the fallen person. |

| Deviations | Union with Sophia can only be achieved through celibacy. This way back to the original state is desirable for all of Christianity. Divine Sophia and earthly Eve are mutually exclusive. | The union with Sophia can also be realized in a Christian marriage. Not all are given the gift of celibacy. Therefore the celibate are not allowed to exalt themselves above the married, but rather they should practice humility, which is the mark of true "virginity". Heavenly and earthly marriage (Sophia and Eva) are analogous to one another. Marriage can form a spiritual community that can proleptically represent the establishment of androgynous unity. Arnold thus carefully distances himself from the marriage-critical point in the earlier script. Sexuality is permissible because it is for reproduction. Now for him there is a pure Christian marriage including sexuality, since the purification consists primarily in the fight against sin. |

The idea of a holy love marriage with Sophia comes from the Sapientia Salomonis: Solomon is seized by the spirit of wisdom, whereby he receives all divine knowledge about the world. Wisdom is the power of creation that communicates to God and makes souls friends of God and prophets (Sap 7,26f). That is why Solomon unites with her:

“2 I have loved and sought this wisdom from my youth and sought to take it as my bride, and I have grown fond of its beauty. 3 She is of splendid nobility, for she is a companion of God and the Lord of all things loves her. 4 For she has been initiated into God's knowledge and participates in his works. "

Correspondingly, Solomon praises sterility, emasculation and childlessness (Sap 3,13f; 4,1f).

The motif that Adam had female parts in himself (androgyny) can be found before Arnold in the Sophia-Imagination von Böhme (1575–1624), the aim of which is to regain this status in which one is no longer seduced by the sex drive to sin . Gichtel adapts Böhme and combines the Sophia doctrine with the rejection of sex and marriage. Even sexual intercourse within marriage is fornication. The Pauline advice from 1 Corinthians 7 to marry in order to prevent fornication is only addressed to Gentiles. With the new birth, procreation ceases and one orientates oneself to Christ, who lived just as celibate. For Gichtel, however, there are also married people who “spiritually circumcise”, that is, lead a sexually abstinent marriage. This also includes Arnold, who, however, left Gichtel's strict line with his marriage (1701) and the fathering of his daughter (1704).

Arnold describes the spiritual marriage with the divine Sophia with erotic images, which are intended to emphasize the incomparability to an earthly woman:

“You can then confidently lie down on her breast and suckle until you are full; and all of your pure powers are open to draw you into yourself in the paradisiacal game of love. There is pure lust in all of her neighboring apartment. An earthly bride can never appear to a man more adorned, chaste, chaste and graceful than this highly praised virgin. "

Quote

"The tyrannizing Clerisey has horribly accused the dearest witnesses of Jesus Christ as heretics."

Entering the tradition

May 30th (the day of his death) is Arnold's memorial day in the Evangelical name calendar .

Arnold is in the Evangelical Hymn book (No. 388) with the song "Oh breakout of all gangs" (1698):

"1. O breaker of all bonds, who you are always with us, where damage, ridicule and shame is pure joy and heaven, furthermore practice your judgment against our sense of Adam until your faithful face leads us out of the dungeon.

2. Is it your father's will that you finish this work; For this purpose, the fullness of all wisdom, love and strength resides in you, so that you do not lose anything of what he has given you and lead it out of the hustle and bustle to the sweet resting place.

3. Oh, you have to complete us, you cannot and will not do otherwise; for we are in your hands, your heart is on us, although we are considered as imprisoned by all people, because the lowliness of the cross despises us and despises us.

4. But look at our chains, since we sigh, wrestle, scream, pray with the creature for redemption from nature, from the service of vanities, which oppresses us so hard, even if the spirit is sometimes ready for something better.

5. If we have caught ourselves in lust and idiosyncrasy, oh, don't let it hang in the death of vanity; because the burden drives us to call out, we all beg you: Just show the first steps of the broken path of freedom!

6. Oh, how dearly we are made not to be servants of men! Therefore, as truely as you have died, you must also make us pure, pure and free and completely perfect, formed according to the best image; he has taken grace for grace whoever fills himself with your fill.

7. Love, draw us into your death; let what your kingdom cannot inherit be crucified with you; introduce us to paradise. But well, you won't delay, let's just not be casual; we will dream as we do when freedom breaks in. "

Fonts

Bibliography of the works of Gottfried Arnold

- Gerhard Dünnhaupt : Gottfried Arnold. In: Personal bibliographies on Baroque prints. Volume 1. Hiersemann, Stuttgart, 1990. pp. 314-352 ISBN 3-7772-9013-0

Old prints

- Dissertatio de locutione Angelorum. Wittenberg December 14, 1687; in: Antje Missfeldt (ed.), see below ( current issues ).

- MGAAM [Magistri Godofredi Arnoldi Artium Magistri] First martyrdom / or Merck-worthy story of the first martyrs faithfully described with the oldest scribbler own words. Quedlinburg 1695.

- The first love of the congregation of Jesus Christ / that is / true illustration of the first Christians / according to their living faith and holy life . Friedeburg, Frankfurt am Main 1696.

- Kurtz chamfered church history / the Old and New Testament. Fritsch, Leipzig 1697.

- Divine love sparks, sprung from the great fire of God's love in Jesus Christ and collected by Gottfried Arnold.

- Part 1, JD Zunner, Frankfurt am Main 1698. Therein No. 126 (of 169): Babels Grab-Lied.

- Part 2 ( Other part of the divine love-funcken. ) JD Zunner, Frankfurt am Main 1701.

- The Signs Of This Time / Bey The Beginning Of The Tribulation That Is Coming. Struntz, Aschersleben 1698.

- Impartial church and heretic history. Fritsch, Leipzig and Frankfurt am Main 1699 f. Digitized (vol. 1), digitized and full text in the German text archive (vol. 2)

- Digitized version of the Frankfurt am Main edition: Thomas Fritschens sel. Erben 1729, copy from the Library of Congress .

- A feast of ancient Christianity consisting in salvation. König, Goslar, Leipzig 1699.

- Frank confession. First edition 1698; Edited for the first time and commented critically by Dietrich Blaufuß in: Antje Missfeldt (Ed.), see below ( Current issues ).

- Godfrid Arnold's Offenhertzige Bekandtnuß / Which Bey recently left his academic office. Papen, Berlin 1699.

- Vitae Patrum Or The Life Of The Elderly Fathers And Other God-blessed Persons. Waysen House, Hall 1700. 1st part , 2nd part

- The Secret Of The Divine Sophia or Whiteness. Fritsch, Leipzig 1700.

- The most correct way through Christ to God. Fritsch, Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig 1700. Digitized

- Gottfried Arnold's exquisite letters from their elders. Calvisius, Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig, Quedlinburg 1700.

- Gottfried Arnold's declaration / On the common sect nature / Going to church and communion; As also from the right gospel. Teaching office / and right-Christl. Freedom. Fritsch, Leipzig 1700. Digitized and full text in the German text archive

- Well-founded remonstration to all high and low authorities / As well as to all other modest and sensible readers / In terms of the compulsion of conscience in the church being. 1700.

- Gottfried Arnold's frank confession / of abandoning his profession. Müller, Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig 1700.

- Poetic sayings of praise and love / from Eternal Whiteness / according to the instructions of Des Hohenlieds Salomonis. 1700.

- Gottfried Arnold's final presentation of his teaching and confession to Mr. D. Veiels, his censor and M. Corvini accusations. Fritsch, Frankfurt am Main 1701. Digitized

- Gottfried Arnold's further explanation of his senses and behavior when going to church and evening meals. Fritsch, Frankfurt am Main, 1701. Digitized

- Supplementa, Illustrationes and Emendationes to Improve Church History. Fritsch, Frankfurt am Main 1703.

- Sincere comments on the bitterly aroused disputes / because of the history of the church and cats of Mr. Arnold. 1703.

- The astray or errors and temptations of benevolent and pious people, piqued out of affection for godly antiquity. Fritsch, Frankfurt am Main 1708.

- The Evangelical Message Of The Glory Of God In Jesus Christ. Fritsch, Leipzig 1727.

- Thomas von Kempis ingenious writings: 24 books and the 4 books of succession, introduction and translation: Gottfried Arnold, 1200+ pages, Leipzig 1733 digitized

Current editions of works

- Antje Missfeldt (Ed.): Gottfried Arnold. Radical pietist and scholar. Böhlau, Cologne 2011, ISBN 978-3-412-20689-5 . In it seven essays by Hanspeter Marti , Arnold's dissertation on the angel language (1687) and his Offenhertzige confession (1698).

- Hans Schneider (Ed.): The first love. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2001. ISBN 3-374-01913-7

- Erich Seeberg (Ed.): Poems and speculative-mystical writing. Langen / Müller, Munich 1934. Selection from: Gottliche Liebes-Funcken (1698, 1701) etc., see above ( writings ) and “Works by Gottfried Arnold at Zeno.org” below ( web links ). NA 2010: ISBN 978-3-8430-5041-8

- Impartial church and heretic history from the beginning of the New Testament to the year of Christ 1688. 4 volumes, Georg Olms, Hildesheim 2008 (3rd reprint of the Frankfurt a. M. 1729). ISBN 978-3-487-01671-9 .

- Main typefaces in separate editions. frommann-holzboog, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1963, 1971.

- Volume 1: The Secret of Divine Sophia or Wisdom. 1963 (Faculty of the Leipzig 1700 edition, foreword by Walter Nigg ), ISBN 3-7728-0012-2 .

- Volume 2: History and Description of Mystical Theology. 1971 (Facs.-Neudr. D. Edition Frankfurt a. M. 1703). ISBN 3-7728-0013-0 .

Auction catalog for Gottfried Arnold's private library

- Catalogus bibliothecae b [eati]. Godofredi Arnoldi, inspectoris et pastoris Perlebergensis. [O. O.], 1714.

Edition and commentary:

- Reinhard Breymayer : The rediscovered catalog for Gottfried Arnold's library. In: Dietrich Blaufuß and Friedrich Niewöhner (eds.): Gottfried Arnold (1666–1714) […]. Wiesbaden, 1995, pp. 55-143 (commentary) and pp. 337-410 (facsimile reprint).

Research literature on Gottfried Arnold

Bibliography of the research literature on Gottfried Arnold

- Hans Schneider [Marburg] ( arr. ): Arnold-Literatur 1714–1993. In: Dietrich Blaufuß and Friedrich Niewöhner (eds.): Gottfried Arnold (1666–1714) […] . Wiesbaden, 1995, pp. 415-424.

Individual works of research literature on Gottfried Arnold

- Dietrich Blaufuß and Friedrich Niewöhner (eds.): Gottfried Arnold (1666–1714). With a bibliography of Arnold literature from 1714. Wiesbaden, 1995.

- Jürgen Büchsel: Gottfried Arnold: His understanding of the church and rebirth. Dissertation. Marburg 1968. Witten 1970.

- Franz Dibelius : Arnold, Gottfried. In: Real Encyclopedia for Protestant Theology and Church . Volume 2. 3rd edition. 1897, pp. 122-124.

- Hermann Dörries : Spirit and History with Gottfried Arnold. Goettingen 1963.

- Gerhard Dünnhaupt : Gottfried Arnold. In: Personal bibliographies on Baroque prints. Volume 1. Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-7772-9013-0 , pp. 314-352.

- Dirk Fleischer: Between tradition and progress. The structural change of Protestant church historiography in the German-speaking discourse of the Enlightenment. Waltrop 2006. pp. 23-69.

- Gustav Frank : Arnold, Gottfried . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1875, p. 587 f.

- Katharina Greschat: Gottfried Arnold's “impartial church and heretic history” from 1699/1700 in the context of his spiritualistic criticism of the church. In: Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte Volume 116. Fourth episode LIV, Issue 1. Kohlhammer, 2005, ISSN 0044-2925 .

- Hanspeter Marti: see Antje Missfeldt above ( current issues )

- Irmfried Martin: The struggle for Gottfried Arnold's "impartial church and heretic history". Dissertation. Heidelberg 1972.

- Peter Meinhold: Arnold, Gottfried. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, ISBN 3-428-00182-6 , p. 385 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Antje Missfeldt (Ed.): Gottfried Arnold. Radical pietist and scholar . Cologne (inter alia) 2011, ISBN 978-3-412-20689-5 .

- Werner Raupp : Arnold, Gottfried (pseudonym: Christophorus Irenaeus). In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 20, Bautz, Nordhausen 2002, ISBN 3-88309-091-3 , Sp. 46-70. (with detailed bibliography).

- Erich Seeberg: Gottfried Arnold. The science and mysticism of its time. Studies in historiography and mysticism. Meerane 1923.

- Hans Schneider: The radical Pietism in the 17th century. In: History of Pietism. Volume 1. Göttingen 1993, pp. 390-437.

- Hans Schneider: The radical Pietism in the 18th century. In: History of Pietism. Volume 2. Göttingen 1995, pp. 107-197.

- Erich Seeberg: Gottfried Arnold - Mystic of the Occident. Edited by RF Merkel. 1934.

- Andreas Urs Sommer : History and Practice with Gottfried Arnold. In: Journal of Religious and Intellectual History . Vol. 54, issue 3. 2002, pp. 210-243.

- Traugott Stählin: Gottfried Arnold's spiritual poetry, faith and mysticism. Dissertation. Göttingen 1963. Printed in 1966.

- Eitel Timm: The political issue of size. Goethe's critique of institutions based on Gottfried Arnold's guideline for depravation theory. In: Goethe Yearbook. Volume 5. 1990. pp. 25-45.

- Werner Raupp : Arnold, Gottfried. In: Heiner F. Klemme, Manfred Kuehn (Ed.): Dictionary of Eighteenth-Century German Philosophers. Volume 1, London / New York 2010, pp. 34–36.

Web links

- Publications by and about Gottfried Arnold in VD 17 .

- Literature by and about Gottfried Arnold in the catalog of the German National Library

- Digitized prints by Gottfried Arnold (theologian) in the catalog of the Herzog August Library

- Works by Gottfried Arnold at Zeno.org .

- Texts by Gottfried Arnold in the voice of faith

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans Schneider: Data on the biography of Gottfried Arnold . In: Dietrich Blaufuß, Friedrich Niewöhner (Ed.): Gottfried Arnold (1666–1714) . Wiesbaden 1995, p. 411-414 .

- ↑ Arnold, Gottfried: Gießen Inaugural Lecture and other documents from his time in Gießen and a duplicated curriculum vitae. Published by Hans Schneider. EPT Volume 4, Leipzig 2012, in it: Arnold's duplicated curriculum vitae, pp. 138–181.

- ↑ a b c d e f Jürgen Büchsel: Arnold's way in the period from 1699 to 1702 . In: Gottfried Arnolds Weg from 1696 to 1705 . Hall 2011, p. 17-99 .

- ^ A b c Hans Schneider: Gottfried Arnold in Giessen . In: Dietrich Blaufuß, Friedrich Niewöhner (Ed.): Gottfried Arnold (1666–1714) . Wiesbaden, S. 267-299 .

- ↑ Hans Schneider can already refer to Max Goebel, Dibelius and Willkomm.

- ↑ biography. Retrieved May 27, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Jürgen Büchsel: From Word to Action: The Changes of Radical Arnold. An example of radical pietism . In: Dietrich Blaufuß, Friedrich Niewöhner (Ed.): Gottfried Arnold (1666–1714) . Wiesbaden 1995, p. 145-164 .

- ^ A b Johann Friedrich Gerhard Goeters: Gottfried Arnold's view of church history in its career . In: Bernd Jaspert, Rudolf Mohr (Ed.): Traditio, Krisis, Renovatio from the theological point of view . Marburg 1976, p. 241-257 .

- ^ Jürgen Büchsel: Continuity and Discontinuity. In: Gottfried Arnolds Weg from 1696 to 1705. Halle 2011, pp. 146–147.

- ^ A b Hans Schneider: Gottfried Arnold's First Love . In: Wolfgang Breul, Lothar Vogel (eds.): Collected essays I. The radical Pietism . Leipzig 2011, p. 186-206 .

- ↑ Gottfried Arnold: First love . In: Hans Schneider (ed.): Small texts of Pietism . tape 5 , 2002, p. 37-58 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Wolfgang Breul: On the quick end of “first love”. The Reformation in Gottfried Arnold's Impartial Church and Heretic History . In: Wolf-Friedrich Schäufele et al. (Ed.): The image of the Reformation in the Enlightenment . Heidelberg 2017, p. 235-251 .

- ↑ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/displayPhoto.pl?path=/service/rbc/rbc0001/2010/2010houdini13674&topImages=0531r.jpg&topLinks=0531v.jpg,0531u.tif,0531a.tif,0531. tif & displayProfile = 0

- ↑ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/displayPhoto.pl?path=/service/rbc/rbc0001/2010/2010houdini13674&topImages=0518r.jpg&topLinks=0518v.jpg,0518u.tif,0518a.tif,0518. tif & displayProfile = 0

- ↑ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=rbc3&fileName=rbc0001_2010houdini13674page.db&recNum=521

- ↑ From my life. Poetry and Truth, Part 2, Book 8 at Zeno.org

- ↑ Wolfgang Breul: Gottfried Arnold and the conjugal and unmarried life . In: Udo Sträter (Ed.): Old Adam and New Creature. Pietism and Anthropology . Tübingen 2009, p. 357-369 .

- ^ A b Hans-Georg Kemper: love / marriage - love marriage. Poetry as the song of praise for a sympathetic gender relationship . In: Wolfgang Breul et al. (Ed.): "The Lord will reveal his glory to us". Love, Marriage and Sexuality in Pietism . 2011, p. 277-298 .

- ↑ https://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/dlf/65045/131/0/

- ↑ Werner Raupp : ARNOLD, Gottfried (pseudonym: Christophorus Irenaeus). In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 20, Bautz, Nordhausen 2002, ISBN 3-88309-091-3 , Sp. 46-70.

- ↑ Gottfried Arnold in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Arnold, Gottfried |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Christophorus Irenaeus (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German theologian and church historian |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 5, 1666 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Annaberg in the Ore Mountains |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 30, 1714 |

| Place of death | Pearl Mountain |