Roger Bacon

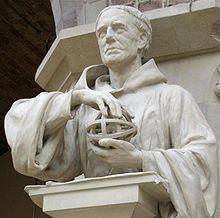

Roger Bacon (* around 1220 , but not before 1214 (traditional indication), near Ilchester in Somerset , † shortly after 1292 in Oxford ), called " Doctor mirabilis " ( Latin , "wonderful / miraculous teacher"), was an English Franciscan and philosopher , especially natural philosopher , and is considered one of the first advocates of empirical methods. He is considered to be one of the most important representatives of late scholasticism .

Life

Roger Bacon's family came from the upper middle class, but was during the reign of Henry III. the property was confiscated and numerous members of the family were driven into exile.

Roger Bacon studied at Oxford University , then gave lectures on Aristotle and pseudo-Aristotelian writings. He was probably a baccalaureus in 1233 and went to France to work as a representative of Aristotelianism at the University of Paris , which was the center of intellectual life in Europe at the time. Between 1242 and 1245, as a Magister Artium , he held well-attended lectures at the Faculty of Artes . He returned to Oxford around 1246. Between 1247 and 1251 he made friends with influential people such as Adam de Marisco (Adam Marsh) and Robert Grosseteste , who influenced his philosophical thinking, as well as Bishop of Lincoln , who promoted the study of the Greek language, to understand Aristotle and the Bible in the "original" to study. He studied mathematics , which also included astronomy and astrology , alchemy and optics, and devoted himself to language learning and experimental research. For his studies - which marked a clear departure from the usual activities of his colleagues - he invested considerable funds from the family fortune.

After about ten years of intense research, he returned to Paris and - physically and mentally exhausted - joined the Franciscan order in 1257. There, however, he was soon suspected of spreading "dangerous" teachings and was placed under strict supervision. Back in the Paris Convention, he came into conflict with the instruction of Bonaventure von Bagnoregio , according to which the consent of the superiors of the order had to be obtained before publications. As a result, he lost his license to teach there. When the family could no longer support him financially either, he looked for a sponsor and believed he had found him in Cardinal Guy le Gros de Foulques , who was very interested in his ideas. In 1266/1267 he wrote three writings for him in quick succession (bypassing the prohibition of his superiors): the opus maius , the opus minus and his opus tertium . The hoped-for success did not materialize, however, as his patron - who was elected Pope ( Clement IV ) in 1265 - died in 1268. In the following years he wrote other writings: the Communia naturalium , the Communia mathematica and the Compendium philosophiae .

Around 1278 he was placed under arrest; the reasons were probably his unbridled attacks against the scholastics and his penchant for mysticism (especially the prophecies of Joachim de Fiore ). In 1292 he was released from arrest and summarized his theses again in a Compendium studii theologiae , in which he sharply criticized contemporary theologians . He died in June 1292 (or 1294), possibly June 11, 1294. Although he was called doctor mirabilis (admirable teacher) by his contemporaries , he had no students and was soon forgotten.

power

Overcoming scholasticism

The scientific training that Bacon enjoyed resulted from studying the Arab authors of the Middle Ages, who regarded Aristotle (or the writings ascribed to him) as the greatest. They showed the shortcomings of academic training in the Occident : Aristotle was only known for poor translations, and hardly any of the professors knew the Greek language . The same was true of the Scriptures. The laws of nature were not recognized through knowledge in the Aristotelian way, but as God-created, everlasting being. The two largest orders, the Franciscans and Dominicans , - although still young - quickly took the lead in the theological discussion.

Bacon had acquired an unusual knowledge of the sciences from Arabic and Greek writings as well as through his own observation and tried to establish a system of empirical philosophy on this basis, which he opposed to scholasticism. Bacon recommended learning the Arabic language (probably also in order to "defeat the Muslims in mastering nature"). He named four offendicula (obstacles) that bar us on the way to a true understanding of nature: 1. Respect for authorities, 2. Custom, 3. Dependence on the marketable opinions of the crowd, and 4. Unteachability of our natural senses (in this respect he was a predecessor of his Namesake Sir Francis Bacon ).

In the end, he completely rejected scholasticism . The only lecturer he recognized was "Petrus de Maharncuria Picardus" or "Petrus from Picardy" (probably identical with the mathematician Petrus Peregrinus from Picardy ). In Bacon's Opus minus and Opus tertium , a huge torrent of abuse pours over Alexander von Hales (whom he had admired in Paris) and another professor who “only learned by teaching others”. His dogmatic writings opened him up in Paris to equality with Aristotle , Avicenna and Averroes . They show that he was a follower of Aristotle, albeit with clear borrowings from Neoplatonism .

In his writings for Clement IV, Bacon called for a reform of theological studies. Philosophical hair-splitting should be emphasized less than it was in scholasticism. Instead, the Bible itself should come back into focus. The study of the scriptures should be done in the native language. (The mistranslations and misinterpretations were legion.) He also urged theologians to study the entire sciences in order to add them to university education.

Insights as a researcher

Bacon rejected the blind allegiance of previous authorities, not only in theological but also in scientific terms. His Opus maius contained chapters on mathematics and optics , alchemy and the manufacture of black powder (which he had one of the earliest mentions in the Latin West and its use in children's fireworks) and the position and size of celestial bodies . He correctly described the laws of reflection and refraction , investigated the formation of the rainbow and the relationship between the tides and the position of the moon.

He is also said to have invented glasses - based on preliminary work by Alhazen . At the same time, he is said to have predicted inventions such as the microscope , telescope , flying machines ( ornithopters ) and steamships.

Although he was considered a proponent of empirical and experimental methods (Scientia experimentalis), this also included “magically” motivated practices, because Bacon had just as little doubt as his contemporaries about the effectiveness of magical practices; but it is difficult, he said, to distinguish between magic and (empirical) science. He believed that the heavenly bodies had an influence on the fate and spirit of people. He also asserted this in his alchemy, the main aim of which was the production of medicines and the extension of life, and in addition the production of a body with perfectly balanced element qualities (corpus aequalis complexionis), whose indestructibility should also be transferred to the human body. His alchemically prepared drugs were based on blood and mercury, among other things, and in this area he was influenced by pseudo-Aristotelian writings, Avicenna or writings attributed to it and Artephius , all writings that originally came from the Arab region and at that time also in the Latin West became known. He exerted a considerable influence on alchemy into the early modern period, with a large number of scriptures being incorrectly ascribed to him.

Bacon criticized the Julian calendar , which was still in use at the time, and made proposals for a calendar reform , which had been "largely" taken over from Robert Grosseteste .

Quotes

In the epistle On the Praises of Scripture , Bacon wrote:

"There is only one perfect wisdom and it is fully contained in the Holy Scriptures."

In his main work Opus maius it says about the role of mathematics:

“All things in heaven (including angels for Bacon) can only be grasped by quantities, as is very evident in astronomy. But mathematics is about quantities. The power of all logical operations also depends on mathematics. [...] The knowledge of mathematical objects is, so to speak, innate in us. So they precede all knowledge and science, [...] so it is the first of all sciences. It is it that enables us to work scientifically. [...] Only in mathematics do we arrive at full, error-free truth, a certainty without error. [...] Only with the help of mathematics can one really know and verify all other statements, because every science only contains as much truth as there is mathematics in it. [...] So after I have shown that one can only know something in philosophy if one knows something in mathematics, and theology cannot be understood without philosophy, it follows that every theologian has to master mathematics. The theologian must be very well informed about the created things, but he cannot do that without mathematics. Mathematics comes closest to divine thinking. "

About the importance of experience and experiment, Bacon said:

“In the natural sciences one can not know anything sufficient without experience and experiment . The argument from authority does not bring certainty, nor does it remove doubt. [...] There are three ways we can know something: authority, reason, and experience. Authority is of no use if it is not based on justification: We believe in an authority, but we do not see anything because of it. But even the justification does not lead to knowledge if we do not check its conclusions through practice (of the experiment). [...] Above all sciences stands the most perfect of them, which verifies all others: it is empirical science that neglects the justification because it does not verify anything unless it is assisted by experiment. Because only the experiment verifies, but not the argument. "

An example of his technical predictions can be found in Epistola de secretis operibus artis et naturae :

"Possunt etiam fieri instrumenta volandi, ut homo sedens in medio instrumenti revolvens aliquod ingeniu, per quod alae artificialiter compositae aerem verberent, ad modum avis volantis."

"Instruments for flying can also be made in which a person sits and operates a certain type of apparatus through which artificial wings move the air, as is the case with birds."

Appreciation

With his demand to turn away from the authorities and towards real things, Roger Bacon was undoubtedly an - out of date - forerunner of this worldly thinking of the Renaissance . But although he wanted to bring experience to science, his thinking was still strongly alchemical and mystical. Around four centuries later, the Enlightenment in Oxford remembered their "predecessor" and made him a "courageous champion of empiricism" against medieval scholasticism.

Bacon was and is sometimes seen as the (co-) author of the so-called Voynich manuscript . The lunar crater Baco (German form of Bacon) and the asteroid (69312) Rogerbacon were named after him.

literature

- Hans Bauer: The wonderful monk . Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 1963 (without ISBN).

- Mara Huber-Legnani: Roger Bacon, teacher of vividness . The Franciscan Thought and Individual Philosophy. In: Philosophy University Collection . tape 4 . Hochschulverlag, Freiburg in Breisgau 1984, ISBN 3-8107-2195-6 (also dissertation at the University of Freiburg 1994).

- Michael Kuper: Roger Bacon. The man who was Brother William's teacher . In: biography . tape 3 . Zerling, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-88468-059-5 .

- Hans H. Lauer: Bacon, Roger. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 128 f.

- Günther Mensching: Roger Bacon . Aschendorff, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-15670-4 .

Works

In German translation:

- Opus maius. A moral-philosophical selection, ed. u. trans. v. Pia Antolic-Piper, Freiburg: Herder 2008.

- Compendium for the Study of Philosophy, ed. u. trans. v. Nikolaus Egel, Hamburg: Verlag Felix Meiner 2015.

- Opus maius. The New Founding of Science, trans. v. Nikolaus Egel u. Katharina Molnar, ed. to note from Nikolaus Egel, Hamburg: Verlag Felix Meiner 2017.

- Opus tertium, Latin-German, ed. u. trans. v. Nikolaus Egel, Hamburg: Verlag Felix Meiner 2019.

Web links

- Literature by and about Roger Bacon in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications by and about Roger Bacon in VD 17 .

- Jeremiah Hackett: Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Pia Antolic-Piper: Entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Digitized in the Medieval and Modern Thought project at Stanford University

- John J. O'Connor, Edmund F. Robertson : Roger Bacon. In: MacTutor History of Mathematics archive .

- Extract from the "Klassiker" by Karl Vorländer: History of Philosophy, 1902 (online edition).

- "Roger Bacon, a Martyr of Science" by Stefan Winkle

- Roger Bacon's re-establishment of science in the 13th century / by Nikolaus Egel

Individual evidence

- ↑ Klaus Kienzler: Roger Bacon OFM. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 8, Bautz, Herzberg 1994, ISBN 3-88309-053-0 , Sp. 547-550.

- ^ JD North: Roger Bacon . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 7, LexMA-Verlag, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-7608-8907-7 , Sp. 940-942.

- ↑ Christoph Helferich: History of Philosophy: From the Beginnings to the Present and Eastern Thinking . Springer-Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-476-00760-5 , pp. 100 f .

- ^ Leonhard Schneider: Roger Bacon, ord. Min. A Monograph Contributing to the History of Thirteenth Century Philosophy. Edited from the sources . Kranzfelder, Augsburg 1873, p. 5.

- ^ Gotthard Strohmaier : Avicenna. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-41946-1 , p. 148.

- ↑ a b Rogerus Bacon: Epistola de secretis operibus artis et naturae . Ed .: Johannis Dee. Hamburgum 1618, p. 37 ( Bayerische Staatsbibliothek digital [accessed on March 28, 2015]).

- ^ William R. Newman, Roger Bacon, in: Claus Priesner , Karin Figala : Alchemie. Lexicon of a Hermetic Science, Beck 1998, p. 68.

- ^ E. Withington: Roger Bacon and Medicine. In: AG Little (Ed.): Roger Bacon Essays [...]. Oxford 1914, pp. 337-258.

- ^ Klaus Bergdolt : Scholastic medicine and natural science at the papal curia in the late 13th century. In: Würzburger medical history reports 7, 1989, pp. 155–168; here: p. 159

- ↑ Ludwig Baur: The influence of Robert Grosseteste on the scientific direction of Roger Bacon. In: Roger Bacon Essays ... Ed. By Andrew G. Little, Oxford 1914, pp. 33-54; here: p. 45

- ↑ Quoted from: Rupert Lay : Die Ketzer, Von Roger Bacon bis Teilhard , Albert Langen · Georg Müller Verlag 1981, p. 33.

- ↑ Quoted from: Rupert Lay : Die Ketzer, Von Roger Bacon bis Teilhard , Albert Langen · Georg Müller Verlag 1981, p. 34f.

- ↑ Cf. Udo Reinhold Jeck: Review of: Mensching, Günther: Roger Bacon. Munster 2009 . In: H-Soz-u-Kult , June 29, 2010.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bacon, Roger |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Doctor Mirabilis |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1220 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Ilchester , Somerset |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 1294 |

| Place of death | Oxford |