Hildegard von Bingen

Hildegard von Bingen (* 1098 in Bermersheim vor der Höhe (place of the baptismal church) or in Niederhosenbach (former residence of the father Hildebrecht von Hosenbach ); † September 17, 1179 in the Rupertsberg monastery near Bingen am Rhein ) was a Benedictine , abbess , poet , composer and a great polymath . In the Roman Catholic Church she is venerated as a saint and doctor of the church . In addition, the Anglican , the Old Catholic and the Protestant Churches commemorate them with memorial days.

Hildegard von Bingen is considered to be the first representative of German mysticism in the Middle Ages . Her works deal with religion , medicine , music , ethics and cosmology , among others . She was also an advisor to many personalities. An extensive correspondence from her has been preserved, which also contains clear admonitions to high-ranking contemporaries, as well as reports on long pastoral trips and her public preaching activities .

On October 7, 2012, Pope Benedict XVI. St. Hildegard to the Church Doctor (Doctor Ecclesiae universalis) and extended her veneration to the universal Church . Her relics are in the parish church of Eibingen .

Life

origin

Hildegard von Bingen was born as the daughter of the noble free Hildebert and Mechtild. Neither the exact date of birth nor the place of birth are given by her or by contemporary biographers. The probable date of birth can be narrowed down to the period between May 1, 1098 and September 17, 1098 based on her handwriting Scivias . Since extensive property of the Hildegards family from Bermersheim vor der Höhe (near Alzey ) went into their later monastery foundation and in one Document a Hiltebertus von Vermersheim and his son Drutwin (known as the name of Hildegard's brother) are mentioned, a birth or at least childhood on Gut Bermersheim is likely. As the tenth child of the parents, she should dedicate her life to the Church ( a tenth to God ).

"[...] and my parents consecrated me to God with sighs, and in the third year of my life I saw such a great light that my soul trembled [...]"

childhood

Hildegard grew up on her father's manor and when she was eight, as was customary at the time, she was offered as an oblate by her parents and given a religious education with Jutta von Sponheim, who was eight years her senior . Jutta had two years earlier at the age of 14 years by the Mainz Archbishop Ruthard the virginal consecration received. The consecrated widow Uda von Göllheim took over this education for three years .

“In my eighth year, however, I was offered to God for spiritual life ( oblata ) and up to my fifteenth year I was someone who saw many things and spoke even more simply, so that even those who heard these things asked in astonishment where they came from and from whom they came. "

In the hermitage on the Disibodenberg

On November 1, 1112, she was locked up with Jutta, from then on her teacher, and a third young woman in an inclusory at or in the Disibodenberg monastery, which had been inhabited by Benedictine monks since 1108 . While Jutta (1108-1113) also on that day in front of Abbot Burchard their profession took off, did this Hildegard later before Bishop Otto of Bamberg , the 1112-1115 imprisoned Archbishop of Mainz Adalbert represented.

After the death of Jutta's in the now grown to the monastery hermitage Hildegard was elected in 1136 to the assembled students to Magistra. There were several arguments with Abbot Kuno von Disibodenberg because Hildegard moderated asceticism , one of the principles of monasticism. So she relaxed the food regulations in her community and shortened the very long prayer and worship times set by Jutta. Open dispute broke out when Hildegard wanted to found her own monastery with her community. The Benedictines of Disibodenberg opposed this decidedly, as Hildegard made their monastery popular.

Beginning of public effectiveness

In leading her followers and to justify her written texts, Hildegard referred to visions that, according to her own account, became irresistibly strong in 1141. Unsure about the divine origin of her visions, Hildegard sought support from Bernhard von Clairvaux in a troubled-sounding letter , who reassured her, but at the same time replied cautiously:

“We rejoice with you about the grace of God that is in you. And as far as we are concerned, we exhort and swear you to regard it as grace and to correspond to it with all the loving power of humility and devotion. […] What else can we teach or what exhortation to do when there is already an inner instruction and an anointing teaches about everything? "

Despite mutual esteem, the two letters are the only correspondence that took place between Hildegard and Bernhard. Since Bernhard's letter did not fully meet the expectations of Hildegard or those around her, it was changed for inclusion in the Rupertsberg Giant Code. In addition, there is a dispute in recent research about whether this short quote, which can be read as a polite evasive maneuver, is not as fictional as the episode about Bernhard's unsuccessful visit to Rupertsberg, at which Hildegard was unfortunately unable to be present. In any case, its recognition - whether fictional or not - has contributed greatly to the recognition of her historical personality.

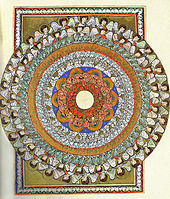

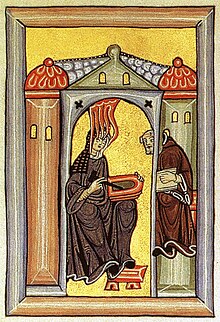

Nevertheless, Hildegard began in 1141 in collaboration with Provost Volmar von Disibodenberg and her confidante, the nun Richardis von Stade , to write down her visions and theological and anthropological ideas in Latin . Since she did not master Latin grammar herself , she had her scribe correct all texts (final secretary: Wibert von Gembloux). Her main work Scivias (“Know the ways”) was created over a period of six years. This book contains 35 miniatures . These miniatures of theological content are extremely artistically painted in bright colors and are mainly used to illustrate the complex and profound text. The original manuscript has been lost since the end of the Second World War; an illuminated copy from 1939 is in the St. Hildegard Abbey in Eibingen.

During a synod in Trier in 1147, Hildegard finally received from Pope Eugene III. permission to publish their visions. This permission also strengthened its political significance. In addition, she was in correspondence with many spiritual and worldly powerful people. Hildegard had numerous visions . In 1141 she experienced an apparition that she understood as God's commission to record her experiences. Unsure about what this vision meant, Hildegard fell ill. In the writing of her visions, Scivias ("Know the ways"), Hildegard writes:

“But I, although I heard these things, refused to write them down for a long time - out of doubt and misbelief and because of the variety of human words, not out of stubbornness, but because I followed humility and that until the scourge of God fell on me and I fell into the sickbed; then, finally moved by various illnesses [...], I gave my hand to the writing. While I was doing it, I felt [...] the deep meaning of the Scriptures; and so I rose myself from the disease by the strength I received and brought this work to its end - just like that - in ten years. […] And I spoke and wrote these things not out of the invention of my heart or any other person, but through the secret mysteries of God, as I heard and received them from the heavenly places. And again I heard a voice from heaven, and she said to me: Lift up your voice and write so! "

The neurologist Oliver Sacks interprets Hildegard's very graphic descriptions of her physical states and visions as symptoms of severe migraines , especially due to the light phenomena (auras) she describes. Sacks and other modern natural scientists suspect that Hildegard suffered from a scotoma , which caused these hallucinatory light phenomena.

Master from Rupertsberg

Between 1147 and 1150 Hildegard founded the Rupertsberg Monastery on the Rupertsberg on the left side of the Nahe . The preserved art objects, especially the gold-purple antependium , bear witness to Rupertsberg's former wealth. It is noteworthy that Master Mathis Gothart Nithart called Grünewald used this monastery Rupertsberg above the Nahe as a model for the monastery church in the Romanesque-early Gothic style, which can be seen in the background of the "Christmas table" of the Isenheim Altarpiece (around 1516); this is proven by a comparison with the copperplate engravings by Daniel Meisner and Matthäus Merian . This assumption is also supported by the fact that Grünewald stayed in Bingen around 1510 and worked as a “water art maker” at Klopp Castle there .

As early as 1151 there were new disputes with clerical officials: The Archbishop of Mainz Heinrich and his brother Hartwig von Stade from Bremen demanded that Richardis von Stade leave the new monastery. Richardis was the sister of the Archbishop of Bremen and was to become the abbess of Bassum Monastery . Hildegard initially refused to release her closest colleague and switched Eugen III. a. Nevertheless, the two archbishops finally prevailed, and Richardis left the Rupertsberg monastery.

After this agreement, Archbishop Heinrich finally confirmed in 1152 the transfer of the monastery property, which had become very extensive due to Hildegard's reputation. This increasing wealth also affected the life of the community and aroused criticism. Several clergymen, but also leaders of other communities, for example Master Tengswich von Andernach, attacked Hildegard because, contrary to the evangelical advice of poverty , her nuns supposedly lived luxuriously and only women from noble families were accepted in Rupertsberg. Since the number of nuns in the Rupertsberg monastery was constantly increasing, Hildegard acquired the vacant Augustinian monastery in Eibingen in 1165 and founded a daughter monastery there, where non-aristocrats could enter, and appointed a prioress there. Hildegard von Bingen died on September 17th, 1179 at the age of 82.

Act

The importance of Hildegard von Bingen can hardly be squeezed into individual categories, as the worldview has changed significantly since the Enlightenment . In her day, great figures were polymaths . Hildegard von Bingen is generally regarded as a person who set new impulses through their own approaches and thus enabled a comprehensive perspective.

Religious and political importance in their time

Her self-confident and charismatic demeanor led to her being well known. She was the first nun to publicly preach conversion to God to the people (including on preaching trips to Mainz, Würzburg, Bamberg, Trier, Metz, Bonn and Cologne). From a letter from Emperor Barbarossa to her, which is controversial in its authenticity and which is handed down in the Wiesbaden Giant Codex, it is concluded that he met her as a consultant in the Ingelheim imperial palace . Even in old age, she still traveled to various monasteries.

Because of her faith and her way of life, she became a guide for many people. Even in her lifetime, many called her a saint. Hildegard justified this view by repeatedly referring to visions for her theological and philosophical statements. In doing so, she secured her teachings against the doctrine that women are incapable of theological knowledge on their own. She described herself as "uneducated". Among other things, she intervened on the side of the Pope in the theological debate about the change of the altar sacrament.

Her moral teaching fascinated not only nuns in her time, but also monks, nobles and lay people. With strong self-confidence, she asserted her interests against others, both out of conviction and to achieve political goals (e.g. at the burial of a wealthy excommunicated person or the denial of the property rights of the Disibodenberg).

Above all, it is the three theological works that established their fame at the time. Her main work Scivias (“Know the ways”) is a doctrine of faith in which the worldview and human image are inseparably interwoven with the image of God. The philosophical-theological overall view, which corresponds in all essential points to church teaching, is presented in 26 visions. The second visionary work Liber vitae meritorum (“Book of Life Earnings ”) could be described as visionary ethics. In it 35 vices and virtues are juxtaposed. The third book Liber divinorum operum ("Book of Divine Works") is Hildegard's show about the world and man. Here it describes the order of creation according to the medieval microcosm - macrocosm conception as something in which body and soul, world and church, nature and grace are made the responsibility of man. With this she also created an early form of Homo signorum .

Her extensive correspondence with high ecclesiastical and secular dignitaries (including Bernhard von Clairvaux ), which has been preserved in around 300 documents, is also part of the complete theological works . In it she shows her extraordinarily strong character and belief in God. For her time, her open words and admonitions, which she led to the king and pope, are particularly remarkable. Her origins and the occupation of the highest church offices by relatives (including her brother Hugo as cathedral cantor of Mainz) gave her the necessary influence to be heard.

Natural and medicinal writings

Hildegard wrote two natural and medicinal works between 1150 and 1160. In contrast to the visionary writings, there are no copies that go back to Hildegard herself or her immediate surroundings. All 13 surviving text witnesses (manuscripts) were created 100 years after her or even later (from the 13th to the 15th century), so that in some cases their authorship has been questioned. In the works that can undoubtedly be attributed to her, however, a text on natural history with the title Liber subtilitatum diversarum naturarum creaturarum ( The Book of the Secrets of the Different Natures of Creatures ) is mentioned. This could mean the large text on the properties and effects of herbs, trees, precious stones, animals and metals, which was later printed under the name Physica . A second work, called Causae et curae ( causes and treatments ), has only survived in a single manuscript. This is a general representation of creation, nature, and especially human nature. The second part deals with individual diseases and their treatment as well as diagnostics. The term " Hildegard Medicine " was only introduced as a marketing term in 1970.

Hildegard's achievement is, among other things, that she brought together the knowledge of diseases and plants from the Greco-Latin tradition with that of folk medicine and (like a previous Innsbruck herb book ) used the German plant names. Above all, however, she developed her own views on the origins of diseases, physicality and sexuality. Furthermore, she condemns all sexual acts which, according to theological understanding, violate the divine order of creation. She did not develop her own medical procedures, but merely brought together known treatment methods from various sources. Hildegard's theory of disease is very similar to the ancient four-juice theory , only with different names. Herbalism from Causae et Curae contains many very direct instructions, each arranged according to symptoms. They are therefore also useful for medical laypeople. For example, it says: “Of tears in your eyes: if you have watery eyes, as if they were watering, you should pick a fig leaf that has been thoroughly moistened with dew during the night, when the sun has already warmed it on its branch, and so on warm on his eyes to restrict their moisture ... "or" When a person's hearing is ruined by some phlegmatic substance or some other kind of illness, take white incense and let smoke rise from it over living fire and let that smoke go ascend into the obduring ear… ”.

The idea of unity and wholeness is also a key to Hildegard's natural and medicinal writings. These are entirely shaped by the fact that salvation and healing of the sick person can only proceed from turning to faith, which alone produces good works and a measured order of life. In these points Hildegard differs greatly from the more rational works of other monastery medicine. Hildegard says: “Man has three paths in which his life is active: the soul, the body and the senses”. Only if these three aspects of lifestyle are observed in a balanced way can a person remain healthy.

Meaning in music

The collection of sacred songs by Hildegard von Bingen, handed down under the name Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum (“Symphony of the Harmony of Heavenly Apparitions”), contains 77 liturgical chants with melodies in diastematic new notation as well as the liturgical drama ( sacred play ) Ordo, preserved in text and musical notation virtutum, which is available in two versions - non-pneumatically in the Scivias vision script and neumed in the later so-called Rupertsberg Giant Codex (Wiesbaden) - and which expresses Hildegard's visionary world of thoughts and images in the purest possible way. The spectrum of chants includes antiphons, responsories, hymns, sequences, a kyrie, an alleluja and two symphoniae.

Hildegard's self-stylization as indocta or illiterata is often misunderstood today. What is meant is a demarcation from a new concept of education. Her attitude towards writing, on the other hand, referred to the older monastic craft of memory art, whereby she tied primarily to a genre from the 5th century: Prudentius ' Psychomachia - an allegorical struggle between the virtues and the vices, which she faced in the Ordo virtutum (" Play of forces ”like the soul, the virtues, the angels, etc.) gave a musical form and a voice through chants - often in an expansive ambitus that spans the plagal and authentic key. Such staging of virtues (virtutes) may have enlivened the church of your abbey as part of a liturgical drama. Hildegard's music occupies a special position in Gregorian chant ; it is characterized by wide pitch ranges and large intervals such as fourths and fifths.

Effect in music

The following more recent works relate directly to Hildegard von Bingen, her music or texts:

-

Sofia Asgatowna Gubaidulina

From the visions of Hildegard von Bingen , for Contraalt Solo, based on a text by Hildegard von Bingen, 1994. -

Peter Janssens

Hildegard von Bingen , a Singspiel in 10 pictures, text: Jutta Richter , 1997. -

Tilo Medek

Monthly Pictures (after Hildegard von Bingen) , Twelve Chants for mezzo-soprano, clarinet and piano, 1997. (text version by the composer) -

David Lynch with Jocelyn Montgomery

Lux Vivens (Living Light): The Music of Hildegard Von Bingen , 1998. -

Alois Albrecht

Hildegard von Bingen , a spiritual game with texts and music by Hildegard von Bingen, 1998. -

Ludger Stühlmeyer

O splendidissima gemma , for alto solo and organ, text by Hildegard von Bingen, 2011. (Premiere May 8, 2011 in Hof (Saale) ). -

Wolfgang Sauseng

De visione secunda for double choir and percussion instruments, 2011. (Premiere June 19, 2011 in Graz as part of the Philipp Harnoncourt symposium, by Arnold Schoenberg Choir Vienna and studio percussion graz ). -

Devendra Banhart

for Hildegard von Bingen , 2013. -

Harald Feller

2 sacred chants after Hildegard von Bingen: O factura dei , O gloriosissimi .

Fonts

- Liber Scivias (around 1150) ("Know the ways")

- Liber vitae meritorum (1148–1163) ("Man in responsibility")

- Liber divinorum operum (1163–1174) ("World and Man")

-

Liber simplicis medicinae or Physica (1151–1158) ("natural history")

- The book of the

- Animals

- Birds

- fishing

- Stones

- Elements

- Trees

- plants

- The book of the

- Liber compositae medicinae or Causae et curae ("medicine")

- Carmina ("songs"), including seven sequences and the Symphoniae harmoniae caelestium revelationum

- Epistulae ("correspondence")

- Vita sancti Ruperti

- Vita sancti Disibodi

- Lingua Ignota ( Hildegard of Bingen's Unknown Language: An Edition, Translation, and Discussion , ed.Sarah Higley)

Afterlife

Places of work

The Disibodenberg monastery was dissolved as a result of the Reformation and fell into disrepair. Today there are extensive ruins to visit.

Rupertsberg Monastery was destroyed by Swedish troops during the Thirty Years War in 1632. The expelled nuns moved to the Eibingen monastery. The ruins were later built over. Today there are remains of five arches of the former monastery church. The place Bingerbrück , which developed around the monastery Rupertsberg, belongs to Bingen am Rhein .

The Eibingen monastery was abolished in 1803 in the course of secularization and partially demolished. One wing of the monastery has been preserved. The monastery church became the parish church of St. Hildegard in Eibingen. Today it is also important as a pilgrimage church, as the shrine with Hildegard's bones is located there. The St. Hildegard Abbey above Eibingen was founded in 1904. However, this abbey owns the rights of the two abbeys Rupertsberg and Eibingen. The abbess of Rupertsberg and Eibingen thus succeeds St. Hildegard.

Worship and customs

canonization

Hildegard was venerated like a saint during her lifetime . In 1228 a first application for canonization was made. An official canonization process was already by Pope Gregory IX. (1227–1241) started but not completed by an investigation initiated by him. In an original document from 1233, three clerics from Mainz certify that they had checked Hildegard's way of life, reputation and writings with positive results on behalf of Pope Hildegard; numerous miracles at Hildegard's grave are also mentioned. Due to opposition from the episcopal cathedral chapter of Mainz , the procedure lasted so long that even the last known attempt at an ordinary canonization procedure under Pope Innocent IV in 1244 did not lead to any result. The episcopal resistance does not seem to have been founded in the person of Hildegard, but in the question of competence for canonization, because Rome had only taken responsibility for canonizations since the 12th century. This is supported by the antependium of the Rupertsberg monastery church from the first half of the 13th century , on which Hildegard with a halo and the bishop of Mainz as the donor who adores her are depicted. Without the conclusion of a canonization procedure that was not necessary at the time, Hildegard's canonization (inclusion in the canon ) took place at the latest in 1584 with the inclusion in the first edition of the Martyrologium Romanum (directory of the saints of the Roman Catholic Church). Her feast day in the liturgy of the Catholic Church and in the calendars of saints and names of the Anglican Church , the Evangelical Church in Germany and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America is September 17th. In some Catholic dioceses in Germany, Remembrance Day is a festival .

The papal bulls sent for larger festivities or anniversaries of the saints bear witness to the great importance of Hildegard; and Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI.) has worked in his time as a professor in Bonn (1959-1963) intensively on the life and writings of Hildegard.

On May 10, 2012, Pope Benedict XVI extended the veneration of St. Hildegard on the whole church and inscribed them in the register of saints. On October 7, 2012, she was appointed Church Doctor .

The relics of St. Hildegard were in the Rupertsberg monastery near Bingen until 1631. During the Thirty Years' War they were saved from destruction by the abbess Anna Lerch von Dirmstein , and since 1641 they have been in the church of the old monastery in Eibingen . The reliquary is located in the chancel of the old monastery, today's parish church of Eibingen.

Eibinger reliquary treasure

As one of the most important women of the Middle Ages, Hildegard was given and collected a large number of relics. These relics , known as the Eibinger reliquary treasure , are, like the Hildegardis shrine itself, in the parish church of St. Hildegard and St. Johannes the Elder. T. in Eibingen . The reliquary is kept in the southern part of the nave in a glass altar. He was also saved from destruction by the Swedes in 1631/1632 by the Rupertsberg abbess Anna Lerch von Dirmstein.

Hildegardis Festival in Eibingen

On September 17th, the feast day of St. Hildegard, a solemn festival in the St. Hildegard Abbey and the city of Eibingen , the Hildegardis Festival is celebrated in Eibingen . It is traditionally divided into the pontifical mass held in the morning and the reliquary procession at noon , which has been taking place since 1857 (founded by Pastor Ludwig Schneider). The reliquary is open to the faithful on this day, and the door at the front of the shrine is only opened on this day. The festival ends with Vespers .

In the arched fields on the left side of the nave of the monastery church of St. Hildegard is a cycle of frescoes with scenes from the life of Hildegard in the style of the Beuron art school .

- Scenes from the Vita of Hildegard von Bingen

Commemoration

From 1741 there are records of the construction of the Hildegardis School in Rüdesheim.

A memorial plaque for them was placed in the Walhalla near Regensburg .

The State Dental Association of Rhineland-Palatinate has awarded the Hildegard von Bingen Prize for Journalism every year since 1995 .

The Federal Health Association awards the Hildegard von Bingen Medal .

The Hildegard-von-Bingen-Gymnasium in the Cologne district of Sülz , the Hildegard-von-Bingen-Gymnasium in Twistringen (Lower Saxony), the Hildegardisgymnasium Bochum, the Hildegardisgymnasium Duisburg, the Hildegardis-Schule Hagen and the Hildegardisschule Bingen am Rhein (high school and vocational trainers School), the Hildegardisschule Münster and the Hildegardisschule in Rüdesheim am Rhein (Realschule) were named after her.

For a list of the churches that are consecrated to St. Hildegard von Bingen, see Hildegard Church .

The Hildegard von Bingen pilgrimage route runs along the stations of her life.

The plant genus Hildegardia Schott & Endl. from the Mallow family (Malvaceae) is named after her.

Societies / research

Hildegard research has meanwhile gained worldwide importance. In Germany and Europe countless diploma theses, research groups and Hildegard societies deal with the writings and the work of the saints. In recent years there has been an increasing interest in the Hildegard works from the United States and Asia. Hildegard Congresses in the USA or Asia testify to the global interest in the subject of nunneries in general and Hildegard in particular.

Film / stage

In February 1982 the Westdeutscher Rundfunk Köln (WDR) hosted a colloquium on the music of Hildegard von Bingen. As a result, in May of the same year the ensemble for music of the Middle Ages " Sequentia " under the direction of Barbara Thornton (1950-1998) and Benjamin Bagby brought the mystery play Ordo virtutum ("Round dance of virtues", "Game of forces") in the Romance language Church Groß St. Martin zu Köln on stage, and on Christmas Eve of the same year this production was broadcast on German television. In the same year, the recording was also released on phonograms (location: Klosterkirche Knechtsteden ) as a double LP Ordo virtutum . The concept came from Barbara Thornton and the executors were the members of the ensemble “Sequentia” and the actors Carmen-Renate Köper as Hildegard and William Mockridge as Diabolus.

For the 900th birthday of St. Hildegard was re-recorded the Ordo Virtutum of “Sequentia” with Franz-Josef Heumannskämper as diabolus and director. The production was performed at the Lincoln Center Summer Festival , the Royal Albert Hall in London, the Church of Notre Dame de Paris and the Melbourne Festival .

The director Margarethe von Trotta (producer: Markus Zimmer ) filmed the life of Hildegard von Bingen in 2008 with the title Vision - From the life of Hildegard von Bingen . Hildegard is played by the actress Barbara Sukowa . The Concorde Filmverleih brought the film on 24 September 2009 in the German cinemas.

In 2008 an audio CD with the Hildegard musical “I saw the world as ONE” by music theater author Pilo was released .

Ten years earlier, the Berlin author, actress and director Nadja Reichardt brought the life of Hildegard von Bingen to the theater stage under the title A Swallow in War . The one-person play has been performed annually since its premiere in 1998. There is also a radio play version.

The author and director Rüdiger Heins wrote and staged a play based on Hildegard's texts in 2010. In Vision of Love he deals with Hildegard's visions. Current topics such as environmental pollution, wars and questions of integration are carried over to the present day on the basis of her writings. The world premiere took place on December 10, 2010 in Bingen. The piece is conceived as an Art in Process , which means that it should change constantly over the years.

Medievalist Hildegard Elisabeth Keller integrated Hildegard as one of five main female characters in the trilogy of the timeless , which appeared at the end of September 2011. Based on Hildegard's letters, visions and vision manuscripts, she wrote and staged a radio play in which Hildegard and three other authors talked about life and work in a fictional encounter outside of time.

See also

Literature (selection)

Work editions

- Giant Codex. RheinMain University and State Library, accessed on October 15, 2017 .

- Paul Kaiser (Ed.): Hildegardis Causae et curae. Leipzig 1903 (in the series Bibliotheca scriptorum graecorum et romanorum Teubneriana ) - first modern edition.

- Jacques Paul Migne : S. Hildegardis Abbatissiae Opera omnia. Paris 1882 (= Patrologiae cursus completus: Series latina , 197)

- Electronic editions on the portal: Bibliotheca Augustana

- Walter Berschin with H. Schipperges: Hildegard von Bingen: Symphonia. Poems and chants. Latin and German. Gerlingen 1995.

- Maura Böckeler : Hildegard, Saint, 1098–1179. Know the ways. Scivias . Translated into German from the original text of the illuminated Rupertsberger Codex and edited by Maura Böckeler, Otto Müller Verlag, Salzburg 1954

- Adelgundis Führkötter OSB (translator and publisher), Hildegard von Bingen: "Now listen and learn so that you blush ..." Correspondence translated from the oldest manuscripts and explained from the sources. (= Herder spectrum 5941). Herder publishing house, Freiburg u. a. 2008, ISBN 978-3-451-05941-4 .

- Mechthild Heieck (ed.): Hildegard von Bingen: The book of God's work. Liber divinorum operum. First complete edition, Pattloch, Augsburg 1998, ISBN 3-629-00889-5 .

- Alfons Huber: The abbess St. Hildegardis myst. Animal u. Art scene book […]. Written down by her chaplain, the monk Volmarus, in the years of the Lord 1150–1160. After the text of the Paris manuscript translated from Latin, explained and with animal drawings from the XII. Century provided by Dr. Alfons Huber, Vienna undated

- Bernward Konermann (ed.): Hildegard von Bingen: Ordo Virtutum - game of forces . Augsburg 1991, ISBN 3-629-00604-3 .

- Peter Riethe : Hildegard von Bingen. The book of plants . Translated from the sources and explained by Peter Riethe. Otto Müller Verlag, Salzburg, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7013-1130-9 .

- Peter Riethe: Hildegard von Bingen. The book of the trees . Translated from the sources and explained by Peter Riethe, Otto Müller Verlag, Salzburg, 2001, ISBN 3-7013-1033-5 .

- Peter Riethe: Hildegard von Bingen. The book of the stones . Translated from the sources and explained by Peter Riethe, Otto Müller Verlag, Salzburg, 3rd, completely changed edition. 1997, ISBN 3-7013-0946-9 .

- Peter Riethe: Hildegard von Bingen. From the elements, from the metals . Edited, explained and translated by Peter Riethe with the assistance of Benedikt Konrad Vollmann. Otto Müller Verlag, Salzburg, Vienna, 2000, ISBN 3-7013-1015-7 .

- Peter Riethe: Hildegard von Bingen. The book of the animals . Translated from the sources and explained by Peter Riethe, Otto Müller Verlag, Salzburg, 1996, ISBN 3-7013-0929-9 .

- Peter Riethe: Hildegard von Bingen. The book of the birds . Translated from the sources and explained by Peter Riethe, Otto Müller Verlag, Salzburg, 1994, ISBN 3-7013-0579-9 .

- Peter Riethe: Hildegard von Bingen. The Book of Fishes . Translated from the sources and explained by Peter Riethe, Otto Müller Verlag, Salzburg, 1991, ISBN 3-7013-0812-8 .

- Ortrun Riha (translator), Hildegard von Bingen. Works Volume II. Origin and Treatment of Diseases. Causae et Curae . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 2012, ISBN 978-3-87071-248-8 .

- Ortrun Riha (translator), Hildegard von Bingen. Works Volume V. Healing Creation - The natural power of nature. Physica . Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 2012, ISBN 978-3-87071-271-6 .

- Walburga Storch OSB (translation and ed.), Hildegard von Bingen: Scivias. Know the ways. A vision of God and man in creation and time . Pattloch, Augsburg 1990, ISBN 3-629-00563-2 .

- Barbara Stühlmeyer OblOSB (translator): Hildegard von Bingen. Works Volume IV. Songs. Symphoniae. Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 2012, ISBN 978-3-87071-263-1 .

- Luca Ricossa: Hildegard von Bingen: Ordo Virtutum. Complete annotated edition with music in original notation and French translation. Geneva (www.lulu.com), 2013.

Secondary literature

- Tilo Altenburg: Concepts of social order in Hildegard von Bingen. Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-7772-0711-7 .

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : HILDEGARD von Bingen. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 2, Bautz, Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-032-8 , Sp. 846-851.

- Barbara Beuys : Because I am sick with love: The life of Hildegard von Bingen. Piper, Munich, ISBN 3-492-23649-9 .

- Maura Böckeler : Saint Hildegard von Bingen dance of virtues Ordo Virtutum ; a Singspiel; Barth, Prudentiana (music); Böckeler, Maura, Berlin: Sankt Augustinus, 1927.

- Christine Büchner : Hildegard von Bingen: a life story. Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main; Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-458-35069-9 .

- Harald Derschka : The four-juices theory as personality theory. To further develop an ancient concept in the 12th century . Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2013, ISBN 978-3-7995-0515-4 , pp. 123-217.

- Harald Derschka: The alleged correspondence between Abbot Hartmann von Kempten and Abbess Hildegard von Bingen. A contribution to the discussion about the authenticity of the Hildegard letters . In: Studies and communications on the history of the Benedictine order and its branches . Volume 130, 2019, pp. 73-87.

- Michaela Diers: Hildegard von Bingen. 5th edition. Dtv, Munich 2005 (= dtv portrait), ISBN 3-423-31008-1 .

- Michael Embach: The writings of Hildegard von Bingen. Studies of their transmission and reception in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. ( Erudiri Sapientiae . Volume 4). Academy, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-05-003666-4 .

- Edeltraut Forster u. a. (Ed.): Hildegard von Bingen. Prophetess through the ages. For the 900th birthday. Herder publishing house, Freiburg u. a. 1997, 2nd edition. 1998, ISBN 3-451-26162-6 .

- Hiltrud Gutjahr OSB u. Maura Záthonyi OSB: Seen in living light. The miniatures of the Liber Scivias of Hildegard von Bingen. explained and interpreted. With an introduction to art history by Lieselotte Saurma-Jeltsch. Published by the St. Hildegard Abbey, Rüdesheim / Eibingen, Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 2011, ISBN 978-3-87071-249-5 .

- Alfred Haverkamp (ed.): Hildegard von Bingen in her historical environment. International scientific congress for the 900th anniversary. September 13 to 19, 1998. Bingen am Rhein . Mainz 2000.

- Josef Heinzelmann : Hildegard von Bingen and her relatives. Genealogical notes. In: Yearbook for West German State History 23 (1997), pp. 7–88.

- Sarah L. Highley (Ed.): Hildegard of Bingen's unknown language. An edition, translation and discussion. Palgrave macmillan, New York 2007, ISBN 978-1-4039-7673-4 .

- Helene M. Kastinger Riley : Hildegard von Bingen . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1997, 4th edition. 2011, ISBN 978-3-499-50469-3 .

- Gundolf Keil : Hildegard von Bingen reception. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil, Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 595 f.

- Hildegard Elisabeth Keller : The ocean in a thimble. Hildegard von Bingen, Mechthild von Magdeburg, Hadewijch and Etty Hillesum in conversation. With contributions by Daniel Hell and Jeffrey F. Hamburger. Zurich 2011 ( Trilogy of the Timeless 3), ISBN 978-3-7281-3437-0 .

- Monika Klaes (ed.): Vita sanctae Hildegardis. Life of St. Hildegard von Bingen. Canonizatio Sanctae Hildegardis. Canonization of St. Hildegard. (= Fontes Christiani . Volume 29). Herder, Freiburg et al. 1998, ISBN 3-451-23376-2 .

- Ursula Koch : The master from Rupertsberg: Hildegard von Bingen - a messenger of love. Historical novel (2009), ISBN 978-3765517129 .

- Antonius van der Linde : Hildegard von Bingen . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 12, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1880, p. 407 f.

- Christel Meier : Hildegard von Bingen. In: Author's Lexicon , 2nd ed., Volume III, 1981, Sp. 1257-1280.

- Barbara Newman: Hildegard von Bingen, sister of wisdom. Herder publishing house, Freiburg u. a. 1997, ISBN 3-451-23675-3 .

- Barbara Newman (Ed.): Voice of the Living Light. Hildegard of Bingen and Her World . Berkeley et al. a. 1998.

- Hermann Multhaupt : Hildegard von Bingen - in his life. Novel biography. St. Benno-Verlag , Leipzig 2013, ISBN 978-3-7462-3737-4 .

- Régine Pernoud : Hildegard von Bingen. Your world, your work, your vision. Herder publishing house, Freiburg u. a. 1997, 2nd edition, ISBN 3-451-23677-X .

- Marianne Richert Pfau, Stefan J. Morent: Hildegard von Bingen: The sound of heaven. In: Annette Kreutziger-Herr , Melanie Unseld (Eds.): European women composers. Volume 1, Böhlau, Cologne 2005, contains CD Ordo Virtutum - version based on Scivias (ensemble for music of the Middle Ages, conducted by Stefan Morent), ISBN 3-412-11504-5 .

- Marianne Richert Pfau: Hildegard von Bingen's Symphonia: An Analysis of Musical Process, Modality, and Text-Music Relations. Dissertation, Stony Brook University, 1990.

- Peter Riethe: Hildegard von Bingen. An enlightening encounter with their natural history and medical literature . Tectum Verlag, Marburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8288-2553-6 .

- Hermann Josef Roth : Misunderstood monastery medicine . Spectrum of Science, March 2006, pp. 84-91 (2006), ISSN 0170-2971 .

- Heinrich Schipperges: Hildegard von Bingen. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 9, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-00190-7 , pp. 131-133 ( digitized version ).

- Heinrich Schipperges: The world of Hildegard von Bingen. Freiburg 1997.

- Hartmut Sommer: The real show - the monasteries of Hildegard von Bingen on the Rhine and Nahe. In: Die große Mystiker Darmstadt, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2008, ISBN 978-3-534-20098-6 .

- Christian Sperber: Hildegard von Bingen. A resilient woman . Aichach 2003, ISBN 3-929303-25-6 .

- Barbara Stühlmeyer : The compositions of Hildegard von Bingen. A research report. In: Contributions to Gregorian chant . 22. ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft, Regensburg 1996, ISBN 3-930079-23-2 , pp. 74-85.

- Barbara Stühlmeyer: Music in the 12th Century. In: Hans-Jürgen Kotzur : Hildegard von Bingen 1098–1179. Verlag Philipp von Zabern , Mainz 1998, ISBN 3-8053-2445-6 , pp. 178-181.

- Barbara Stühlmeyer: The songs of Hildegard von Bingen. A musicological, theological and cultural-historical investigation. Olms, Hildesheim 2003, ISBN 3-487-11845-9 .

- Barbara Stühlmeyer: In a sea of light. Healing chants by Hildegard von Bingen. With illustrations by Sabine Böhm. Butzon & Bercker, Kevelaer 2004, ISBN 3-7666-0593-3 .

- Barbara Stühlmeyer: The musical church teacher. On the canonization of Hildegard von Bingen. In: Musica sacra (magazine) No. 5, Bärenreiter Kassel 2011, p. 298. ISSN 0179-356X .

- Barbara Stühlmeyer: The uncomfortable teacher or: why Hildegard von Bingen was holy so late. In: Karfunkel 96 October / November 2011, pp. 27–31.

- Barbara Stühlmeyer: Virtues and Vices. Direction in dialogue with Hildegard von Bingen. With illustrations by Sabine Böhm. Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 2012, ISBN 978-3-87071-287-7 .

- Barbara Stühlmeyer: Paths into his light. A spiritual biography about Hildegard von Bingen. Beuroner Kunstverlag, Beuron 2013, ISBN 978-3-87071-293-8 .

- Barbara Stühlmeyer: Hildegard von Bingen. Life - work - worship. Topos plus Verlagsgemeinschaft, Kevelaer 2014, ISBN 978-3-8367-0868-5 .

- Josef Sudbrack : Hildegard von Bingen: Look at the cosmic wholeness. Echter, Würzburg 1995, ISBN 3-429-01696-7 .

- Victoria Sweet: Rooted in the Earth, Rooted in the Sky: Hildegard of Bingen and Premodern Medicine . New York: Routledge 2006, ISBN 0-415-97634-0 .

- Melitta Weiss-Amer [= Melitta Weiss Adamson]: The 'Physica' Hildegards von Bingen as a source for the 'Master Eberhards cookbook'. In: Sudhoff's archive. 76: 1, pp. 87-96 (1992); see. in addition: Anita Feyl: The cookbook of Eberhard von Landshut (first half of the 15th century). Ostbairische Grenzmarken 5 (1961), pp. 352-366.

- Berthe Widmer : Order of salvation and current events in the mysticism of Hildegard von Bingen (= Basel contributions to historical science. Volume 52). Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel / Stuttgart 1955 (dissertation, University of Basel, 1953).

- Sara Salvadori: Hildegard von Bingen. A journey into the images. Skira, Milan 2019.

Sound carrier (CD)

- A feather on the breath of God - sequences and hymns by Abbess Hildegard of Bingen . Gothic Voices with Emma Kirkby, headed by Christopher Page. Hyperion 1982.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Ordo virtutum / game of forces . Sequentia , headed by Barbara Thornton, Benjamin Bagby. German Harmonia Mundi 1982.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Symphoniae / Spiritual Chants . Sequentia, headed by Barbara Thornton, Benjamin Bagby. German Harmonia Mundi 1985.

- Hildegard von Bingen and her time . Ensemble for early music Augsburg. Christophorus 1990.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Canticles of ecstasy / Gesänge der Ekstase . Sequentia, headed by Barbara Thornton, Benjamin Bagby. Deutsche Harmonia Mundi / BMG 1994.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Voice of the blood / Voice of the blood . Sequentia, headed by Barbara Thornton, Benjamin Bagby. Deutsche Harmonia Mundi / BMG 1995.

- Symphony Of The Harmony Of Celestial Revelations - The Complete Hildegard Von Bingen - Volume One Sinfonye, cond. Stevie Wishart . Celestial Harmonies 1996.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Femina Forma Maria . Marian songs of the Villaren Codex. Ensemble Mediatrix, headed by Johannes Berchmans Göschl . Calig, Augsburg 1996.

- Hildegard von Bingen - O vis aeternitatis . Vespers in the Abbey of St. Hildegard . Schola of the Benedictine Abbey of St. Hildegard, Eibingen, headed by Johannes Berchmans Göschl, Sr. Christiane Rath OSB. Ars Musici, Freiburg 1997.

- Hildegard von Bingen - O Jerusalem . Sequentia, headed by Barbara Thornton, Benjamin Bagby. Deutsche Harmonia Mundi / BMG 1997.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Ordo virtutum. Game of Forces - version after Scivias . Ensemble ordo virtutum, conducted by Stefan Morent. Bayer Records 1997.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Ordo virtutum . Sequentia, headed by Barbara Thornton, Benjamin Bagby. Deutsche Harmonia Mundi / BMG 1998.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Saints . Sequentia, headed by Barbara Thornton and Benjamin Bagby. Deutsche Harmonia Mundi / BMG 1998.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Ordo virtutum - a medieval mystery play . Ensemble A Cappella, Cologne, directed by Dirk van Betteray . OKK, Waldbröl 1998.

- Hildegard von Bingen and Birgitta of Sweden . Les Flamboyants. Raumklang 1998.

- Lux Vivens (Living Light) - The Music of Hildegard von Bingen . Jocelyn Montgomery and David Lynch. Mammoth Records 1998.

- Aurora (The Complete Hildegard Von Bingen Volume Two) Sinfonye, conducted by Stevie Wishart. Celestial Harmonies 1999.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Ordo virtutum . Cantoria Alberto Grau, head of Johannes Berchmans Göschl. Legato 1999.

- The Complete Hildegard von Bingen volume 3 - O nobilissima viriditas Sinfonye, conducted by Stevie Wishart. Celestial Harmonies 2004.

- Seraphim - Hildegard von Bingen . Ensemble Cosmedin, Stephanie and Christoph Haas. Animato 2005.

- Visions of Paradise - A Hildegard von Bingen Anthology . Sequentia. Deutsche Harmonia Mundi / SONY Classics 2009.

- The ocean in a thimble. Hildegard von Bingen, Mechthild von Magdeburg, Hadewijch and Etty Hillesum in conversation. Radio play by Hildegard Elisabeth Keller. 2 audio CDs. VDF-Verlag 2011.

- Hildegard von Bingen - but you have no fear . Ensemble Cosmedin. Two thousand and one edition, 2012.

- Hildegard von Bingen - inspiration . Ensemble VocaMe, conducted by Michael Popp . Berlin Classics 2012.

- Hildegard von Bingen - Celestial Hierarchy . Sequentia, Head Benjamin Bagby. German Harmonia Mundi (SONY) 2013.

- Living light - songs by Hildegard von Bingen and improvisations , Margarida Barbal (vocals), Catherine Weidemann (psaltery), Psalmos 2016.

- Hildegard von Bingen - The Complete Edition . Sequentia, headed by Barbara Thornton, Benjamin Bagby. SONY 2017.

Movie

- Vision - From the life of Hildegard von Bingen , German-French historical film by Margarethe von Trotta (2009)

Web links

- Literature by and about Hildegard von Bingen in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Hildegard von Bingen in the German Digital Library

- Hildegard von Bingen in the repertory "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages"

- Lexical article about Hildegard von Bingen at MUGI (music and gender on the Internet)

- St. Hildegard Abbey Eibingen Website of St. Hildegard Abbey

- Literature about Hildegard von Bingen in the Hessian Bibliography

- Works by Hildegard von Bingen in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Working aid of the German Bishops' Conference, 2012

- Land of Hildegard von Bingen - the portal information portal of the city administration of Bingen am Rhein

- Hildegard von Bingen's works in the Bibliotheca Augustana

- Models of the former monastery of Bingen

- Discography

- Karl Cardinal Lehmann on June 3, 2012 in SWR 2: “St. Hildegard von Bingen - Doctor of the Church "

- Projection area Hildegard contribution in: Herder Korrespondenz No. 6, 2012.

Remarks

- ^ Apostolic letter of Benedict XVI. from October 7, 2012 in Latin and German

- ^ Sermon by Pope Benedict XVI. for the opening of the Synod of Bishops and the exaltation of St. John of Avila and St. Hildegard von Bingen to church teachers on October 7, 2012 ; Vatican Radio from May 27, 2012: "Hildegard von Bingen becomes a doctor of the church" ; Hildegard von Bingen and Johannes von Avila new church teachers

- ↑ Marianna Schrader, Adelgundis Führkötter: The Origin of Saint Hildegard. In: Sources and treatises on the Middle Rhine church history . Volume 43, 2nd edition. Mainz 1981, pp. 14, 18.

- ↑ Dagmar Heller : Hildegard von Bingen . (1098-1179). In: Helmut Burkhardt and Uwe Swarat (ed.): Evangelical Lexicon for Theology and Congregation . tape 2 . R. Brockhaus Verlag, Wuppertal 1993, ISBN 3-417-24642-3 , p. 907 .

- ↑ a b Klaes 1998, p. 125.

- ^ Heinrich Schipperges: The world of Hildegard von Bingen. Life, work, message . HOHE, Erftstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-86756-073-3 , p. 36 .

- ↑ Year after Jutta's Vita ( Franz Staab : Reform und Reformgruppen im Erzbistum Mainz. From 'Libellus de Willigisi consuetudinibus' to 'Vita domnae Juttae inclusae'. In: Reform idea and reform policy in the Late Sali-Early Staufer Empire , Ed. Stefan Weinfurter with the collaboration of Hubertus Seibert, Mainz 1992 (sources and treatises on church history in the Middle Rhine region 68)). On the other hand, Hildegard's Vita reports that she was locked up on the Disibodenberg at the age of eight. (Monika Klaes (Ed.): Vita Sanctae Hildegardis. (Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio mediaevalis 126). Brepols, Turnholti 1993., ISBN 2-503-04261-9 , I, 1, p. 6)

- ^ Alfred Haverkamp: Hildegard von Disibodenberg-Bingen. From the periphery to the center. In: Alfred Haverkamp (ed.): Hildegard von Bingen in her historical environment. International scientific congress for the 900th anniversary. September 13 to 19, 1998. Bingen am Rhein . Mainz 2000. Notes 5 and 73

- ↑ Klaes 1998, p. 14.

- ↑ Hildegard von Bingen: In the fire of the dove: the letters . Transl. And ed. by Walburga Storch. Pattloch, Augsburg 1997, ISBN 3-629-00885-2 , p. 21; see. the interpretation of the correspondence with Christian Sperber, Hildegard von Bingen. A Resistant Woman, Aichach 2003, pp. 92–115.

- ↑ Michael Embach: The writings of Hildegard von Bingen: Studies on their transmission and reception in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period . Habilitation University of Trier, Berlin 2003.

- ↑ Michael Zöller: God shows his people their ways. The theological conception of the Liber Scivias by Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179). Tübingen 1997 (= Tübingen Studies on Theology and Philosophy , 11).

- ↑ Ute Mauch: Hildegard von Bingen and her treatises on the Triune God in Liber Scivias (Visio II, 2). A contribution to the transition from speaking pictures to words, writing and pictures. In: Würzburger medical history reports 23, 2004, pp. 146–158.

- ↑ Oliver Sacks: Migraine: Understanding a Common Disorder. Berkeley, 1985, pp. 106-108; Ines Perl: Tracking down the migraine aura, University of Magdeburg, January 2001

- ↑ Meisner / Kieser: Thesaurus philopoliticus or Politisches Schatzkästlein, facsimile reprint with introduction and register by Klaus Eymann, Verlag Walter Uhl, Unterschneidheim 1972, 2nd book, 2nd part, no.43

- ↑ Matthäus Merian: Topographia Archiepiscopatum Moguntinensis, Trevirensis et Coloniensis, edited by Lucas Heinrich Wüthrich, Kassel / Basel 1967, page 15ff.

- ↑ Pantxika Béguerie-De Paepe / Magali Haas: The Isenheim Altarpiece - The Masterpiece in the Musée Unterlinden, Paris 2016, p. 25

- ↑ Hildegard replied coolly to Tengswich's letter without going into the individual allegations. Only with regard to the separation of noble and non-noble nuns does she remark that it is difficult for the various classes to live together without conflict. Cf. Hildegard von Bingen: In the fire of the dove: the letters . Transl. And ed. by Walburga Storch. Pattloch, Augsburg 1997, ISBN 3-629-00885-2 , pp. 110-114.

- ↑ The questionable tips of St. Hildegard. In: Die Welt , October 4, 2012.

- ↑ The big business with Hildegard von Bingen. In: Der Standard , July 5, 2013.

- ↑ Cf. also Barbara Fehringer [-Tröger]: The "Speyerer Herbal Book" with Hildegard von Bingen's medicinal plants. A study on the Middle High German “Physica” reception with a critical edition of the text. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1994 (= Würzburg medical-historical research , supplement 2).

- ↑ Irmgard Müller: The herbal remedies with Hildegard von Bingen. Healing knowledge from monastery medicine (1st edition Salzburg 1982); Reprint Freiburg im Breisgau / Basel / Vienna 1993 (= Herder / Spektrum , 4193) . 2nd Edition. Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-451-05945-2 , pp. 13 .

- ↑ Barbara Stühlmeyer: The songs of Hildegard von Bingen. A musicological, theological and cultural-historical investigation, dissertation, Olms 2003.

- ^ M. Carruthers: The Craft of Thought, Cambridge etc. 1998.

- ↑ MR Pfau, SJ Morent: Hildegard von Bingen: Der Klang des Himmels, Cologne 2005.

- ↑ Gubaidulina, From the Visions

- ↑ Hildegard von Bingen: Natural history. The book of the inner being of the different natures in creation , translated and explained by Peter Riethe, Salzburg 1959, 3rd edition, ibid. 1980.

- ^ Raimund Struck: Hildegardis De lapidibus ex libro simplicis medicinae: Critical edition comparing other lapidaries. Medical dissertation Marburg 1985.

- ^ Heinrich Schipperges : The world of the elements with Hildegard von Bingen. In: Josef Domes, Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard Dietrich Haage, Christoph Weißer, Volker Zimmermann (eds.): Light of nature. Medicine in specialist literature and poetry. Festschrift for Gundolf Keil on his 60th birthday. Kümmerle, Göppingen 1994 (= Göppinger Arbeit zur Germanistik , 585), ISBN 3-87452-829-4 , pp. 365–383.

- ↑ Hildegard von Bingen: Heilkunde , translated from the sources and explained by Heinrich Schipperges, Salzburg 1957.

- ↑ Digital copy of the certificate at the Virtual German Certificate Network . A regest of the document is available on the website of the Koblenz State Main Archive (click to: Holdings → State Main Archive Koblenz → A The Age of the Old Empire → A.2 Monasteries and Monasteries → Holdings No. 164 Rupertsberg → Finding Book → Documents → Document No. 14) .

- ^ Martyrologium romanum, 9th edition. Rome 1749, Chapter September: http://www.breviary.net/martyrology/mart09/mart0917.htm ( Memento of May 20, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) .

- ^ Abbess, Mystic , accessed November 3, 2012.

- ↑ Entry in the ecumenical dictionary of saints , accessed on September 17, 2013.

- ↑ Promulgazione di decreti della congragazione delle cause Dei Santi. May 10, 2012

- ^ Homepage of the Hildegardis School Rüdesheim History ( Memento from June 14, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ note in the medical journal Nordrhein 6/97 (accessed July 2009) (PDF, 40 kB)

- ↑ Lotte Burkhardt: Directory of eponymous plant names - Extended Edition. Part I and II. Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin , Freie Universität Berlin , Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-946292-26-5 doi: 10.3372 / epolist2018 .

- ↑ Supplement to the double LP Ordo virtutum from 1982 and the double CD Ordo virtutum from 1990.

- ↑ Medieval epic: Margarethe von Trotta had her vision of Hildegard von Bingen. Margarethe von Trotta had her vision from Hildegard von Bingen. In: Moviepilot. September 26, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2018 .

- ↑ Hildegard Musical ( Memento from January 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Short portrait ( Memento from July 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Nadja Reichardt at the DMP Doku-Medienproduktion publishing house

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hildegard von Bingen |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | St. Hildegard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German mystic; Author of theological and medical works; Composer of sacred songs |

| DATE OF BIRTH | between May 1, 1098 and September 17, 1098 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bermersheim vor der Höhe near Alzey |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 17, 1179 |

| Place of death | Rupertsberg Monastery near Bingen |