Scivias

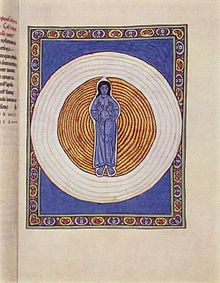

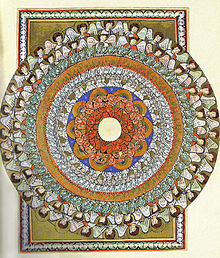

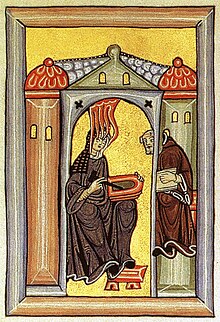

Scivias (dt. Know the ways ), also known as Liber scivias (more rarely illuminated Hildegard Codex ), is an illustrated work of Christian mysticism by Hildegard von Bingen OSB that was created in 1151 or 1152 . In it she describes a total of 26 religious visions that she experienced herself . Scivias is Hildgard's first work and is one of her best known books. Handwritten on parchment in the Romanesque style and in Latin , it marks the start of a trilogy of visions . It was followed by the books Liber vitae meritorum and De operatione Dei (the latter also known as Liber divinorum operum ).

Contemporary manuscripts

A single of around 10 individual manuscripts made during Hildegard's lifetime have survived into modern times. The time it was built is estimated to be around 1175. However, it has been considered lost since the last days of World War II . In addition to this copy, designated by science as manuscript no. 1 , there is only one other contemporary manuscript . This, the so-called manuscript no.2, is not a monographic copy of Scivias, but an element of the Rupertsberg Codex , a summary of all non-medical and non-medicinal works by Hildegard, along with various letters to the Pope , Kaiser and others. This code is kept in the RheinMain University and State Library and is considered the most valuable book in the collection.

Hildegard's original manuscript from 1151 or 1152 was lost over the centuries and there are no reliable findings about possible deviations from manuscripts 1 and 2 . Nevertheless, in the general and scientific context, the manuscript ( manuscript no. 1 ) prepared around 1175 is considered the Scivias manuscript and is the subject of research, translation, discussion and publication. Here, the authorship could be with Hildegard himself, in contrast to manuscript No. 2 , in which paleographic investigations have shown that three copyists (A, B, C) and two rubricators were involved in the production of the manuscript. A writes without interruption to fol. 58v the entire text, the lists of the Capitula and on fol. 1-12 also the rubrics, before this abruptly with line 19, fol. 58 (second sheet of the eighth position) and can no longer be proven later. B takes over the text to the end. C writes from fol. 55v rubrics and also appears in both A and B as a corrector and also takes over all text changes on shave.

Intention of the work

The meaning and purpose of the mystical work are revealed in the eleventh vision of the third part of the divine voice:

“But now the Catholic faith is wavering among the peoples and the gospel is on weak feet with these people. Even the thick volumes, which the experienced teachers had edited with great zeal, dissolve in shameful weariness and the food of the divine scriptures has become tepid. That is why I am now speaking about the Scriptures through an unspoken person; he is not instructed by an earthly teacher, but I, who am I, proclaim new secrets and much mystical things through him that were previously hidden in the books "

Book title

The title Scivias or Liber scivias goes back to the Latin phrase Sci vias [Domini] (dt. Know the ways [of the Lord]! ). The title is a contraction of the two words sci and vias . Liber ( dt. Book ) identifies the work as a book ( vision literature ) to distinguish it from other literary categories that could also be considered due to the elements included, including song books, illustrated books and theater pieces.

Scope and original structure of manuscript No. 1

The . Hand No. 1 (built around 1175) has a total volume of 242 pages in a format - in the High Middle Ages cm 32.5 × 23.5 - usual. The book is divided into three parts (original structure: Pars I fol. 2r – 41r, Pars II fol. 41r – 122r, Pars III fol. 122r – 234v). Textually, the first and second parts have almost the same scope, while the third takes up over half of the work.

Structure and content of manuscript No. 1

At the beginning, Hildegard describes in the prologue how she was commissioned to write down her visions in order to make them accessible to others. In the following Part 1, she describes six visions that deal with Genesis and the Fall of man . The second part includes seven visions that deal with salvation through Jesus Christ , the Christian Church and the sacraments . In the third and prophetic part, she deals with a further 13 visions, all of which relate to the coming kingdom of God and deal primarily with the topics of sanctification and the increasing tension between good and evil. The salvation event is described in the allegory of a mighty building in all its individual parts and led to the Last Judgment . The last vision in praise of the saint is treated in great detail as the “finale”; this is accompanied by a description along with 16 detailed commentaries, 14 songs and a liturgical drama.

The following fine structuring of the book follows the illuminations and uses the titles assigned by Sr. Adelgundis Führkötter (St. Hildegard Abbey), the editor of the critical edition (there are no titles in the original text). If multiple titles are specified, multiple illuminations are provided. Hildegard allows comments to follow each vision, which can be viewed as sections or functional titles. Their number is given in brackets.

- prolog

- First part

- God the light giver and humanity (6)

- The Fall (33)

- God, Cosmos and Humanity (31)

- Humanity and Life (32)

- The synagogue (8)

- The choirs of angels (12)

- Second part

- The Redeemer (17)

- The Triune God (9)

- The Church as Mother of the Believers - Baptism (37)

- Anointed with Virtue - Confirmation (14)

- The Hierarchy of the Church (60)

- The sacrifice of Christ and the Church; Continuation of the mystery in participation in the victim (102)

- Struggle of humanity against evil; The Tempter (25)

- third part

- The allmighty; The extinct stars (18)

- The building (28)

- The tower of preparation; The Divine Virtues in the Tower of Preparation (13)

- The Pillar of God's Word ; Knowledge of God (22)

- The Zeal of God (33)

- The Triple Wall (35)

- The Trinity Pillar (11)

- The pillar of humanity the Redeemer (25)

- The tower of the church (29)

- The Son of Man (32)

- The end of time (42)

- The day of the great revelation ; The new heaven and the new earth (16)

- Praise of the Holy (16)

Book decoration of manuscript number 1

- 35 six-color illuminations, d. H. Illustrations decorated with gold and silver (16 full-page, 15 half-page, 4 quarter-sheet-sized)

- three black and white illustrations

- 27 magnificent initials with gold and silver sections

Loss and content / visual preservation of manuscript No. 1

The last owner of manuscript no. 1 was St. Hildegard Abbey in Rüdesheim , which entrusted it to the Hessian State Library in Wiesbaden for research and safekeeping. There the work, listed under the illuminated Hildegard Codex , was the most precious manuscript and was therefore brought to Dresden together with other precious writings in 1942 to protect against Allied air raids on Wiesbaden and has since been kept in the Girozentrale Sachsen . Witnesses reported that the bunker-like vault there survived the heavy air raids on Dresden in 1944 and 1945 unscathed. According to its directors, the Girozentrale was occupied by Soviet troops immediately after the city was taken and the depots were taken into custody. After approval by the bank, the contents of the deposit and with it the handwriting No. 1 including the sheet metal box in which it was packed and sealed , disappeared. The hopes of many that German reunification would lead to recovery were not fulfilled. The manuscript no. 1 but was fortunately copied exactly before their loss of nuns of the Abbey of St. Hildegard between 1927 and 1933 by hand (incl. 35 illuminations in true color) and thus preserved. In addition, the Hessian State Library of Cologne made the manuscript available as an exhibit for the Millennium Exhibition in 1925 . On this occasion, Professor Neuss commissioned a photographer to head the manuscript section , who recorded the original drawings on photo plates measuring 18 × 24 cm.

influence

In Hildegard's time, Scivias was her best-known work. It was a model for Elisabeth von Schönau and her work Liber viarum Dei . Like Hildegard, Elisabeth had numerous visions and was encouraged by Scivias to publish them as well.

Hildegard's liturgical drama in the course of the remarks on the 13th vision of the third part could be regarded as the first morality at all. The beginnings of this genre are ascribed to the 14th century and were very likely strongly influenced by Hildegard.

criticism

Hildegard can be located within the prophetic tradition of the Old Testament with formulaic expressions. Like these prophets , she was politically and socially engaged and accordingly frequently offered moral admonitions and instructions. Scivias can essentially be seen as a work of guiding the way to salvation . Theological questions arise and are dealt with, but mostly solved by inferences from analogy (especially visual analogies ) and not by logic or dialectics . She creates a metaphysical concept that is difficult to grasp , which she named Viriditas and which she regarded as an attribute of divine nature. Viriditas is contextually translated into German in different ways: freshness, vitality, fertility, green or growth and used as a metaphor for physical and mental health.

Some authors, such as Charles Singer , suggest that the properties of the verbally described visions, as well as the illustrations themselves, which show bright lights and imply auras , may have been caused by the iridescent scotoma in migraines , Oliver Sacks in his book Migraine, called their visions “undeniable migraine, ”but explained that this did not invalidate their visions. The similarity of the illuminations with the typical symptoms of migraine attacks, especially in cases where they are not exactly described in the text, is a strong argument that Hildegard's visions could sometimes be mere imaginations.

It is also believed that the visions at certain times of the year can be traced back to the hallucinogenic ergot , which is very common in this area of the Rhineland.

Editions

- Facsimile edition ( handwriting ) of the Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt (ADEVA) - Graz , 181 copies, 242 pages (original volume of manuscript No. 1 )

- German translation, BÖCKELER, Maura (1954): Know the ways. Scivias. Salzburg : Otto Müller Verlag

- English translation, HOZESKI, Bruce (1986): Scivias . Santa Fe: Bear and Company Print, 1986.

- Critical Edition, (English), FÜHRKÖTTER, Adelgundis / CARLEVARIS Angela et al. (1978): Hildegardis Scivias . Turnhout: Brepols, 1978. LX, 917 pages, with 35 illuminations in color and three black-and-white illustrations.

- Hiltrud Gutjahr OSB, Maura Záthonyi OSB, seen in living light. The miniatures of the Scivias of Hildegard von Bingen, explained and interpreted. (2011): With an introduction to art history by Lieselotte Saurma-Jeltsch, ed. St. Hildegard Abbey , Eibingen. Beuroner Kunstverlag, ISBN 978-3-87071-249-5 .

See also

- Vision - From the life of Hildegard von Bingen , German historical film from 2009

Web links

- Introduction - the miniatures of the illuminated Rupertsberg “Scivias” Codex , all 35 illustrations in color with explanations, St. Hildegard Abbey , Bingen am Rhein .

- Digitized images of MS 160, Merton College, Oxford , Oxford University manuscript (not illustrated).

- Youtube video , Illuminations of the Scivias, underlaid with the song O vis aeternitatis (in English: O, power in eternity ; from the 13th vision of the third part).

- Scivias . Publications in the bibliographic database of the Regesta Imperii .

- Scivias by Hildegard von Bingen , first digitized set from the Salem manuscripts in Heidelberg, Zwiefalten manuscript (end of the 12th century) and Salem manuscript (around 1220).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Facsimile Liber scivias , Ziereis Faksimiles, accessed on December 6, 2017

- ↑ Hildegard of Bingen: An Integrated Vision , KING-LENZMEIER, Anne H. (2001): Collegeville, Minnesota, Liturgical Press, p. 31

- ↑ Introduction - the miniatures of the illuminated Rupertsberg “Scivias” Codex , ed . St. Hildegard Abbey , Bingen am Rhein , accessed on December 8, 2017

- ↑ a b c d Land of Hildegard , ed. City administration Bingen am Rhein , Klopp Castle, accessed on December 7, 2017

- ↑ manuscripta mediaevalia, HSK0737 page b001 , ZEDLER, Gottfried: The manuscripts of the Nassauische Landesbibliothek zu Wiesbaden. 63. Supplement to the Zentralblatt zum Libraries. Leipzig: Harrassowitz, 1931, accessed on December 9, 2017

- ↑ a b c d e f Scivias , (1979) in pdf format, ed. Hildegard Schönfeld with the collaboration of Wolfgang Podehl et al. , Bingen am Rhein , accessed on December 9, 2017

- ↑ Hildegard of Bingen: An Integrated Vision , KING-LENZMEIER, Anne H. (2001): Collegeville, Minnesota, Liturgical Press, p. 30

- ↑ Hildegard of Bingen: A Spiritual Reader , BUTCHER, Carmen Acevedo (2007), Brester, MA: Paraclete Press, page 51.

- ↑ Correspondent , FERRANTE, Joan (1998): Page 91-109, essay in Voice of the living light: Hildegard of Bingen and her world. The psychological and social uses of prophecy , ed .: NEWMANN Barbara, Univ. of California Press, p. 104, accessed December 9, 2017

- ^ Parallel Patterns in Prudentius's Psychomachia and Hildegard of Bingen's Ordo Virtutum. , HOZESKI, Bruce W. (1982): Pages 8-20, essay, in Voice of the living light: Hildegard of Bingen and her world. The psychological and social uses of prophecy , Ed .: 14th Century English Mystics Newsletter, 1982, Volume 8, No. 1, accessed on December 9, 2017

- ↑ Hildegard of Bingen. The psychological and social uses of prophecy , FLANAGAN, Sabina Florence (1985): Dissertation University of Adelaide , page 61, accessed December 9, 2017

- ↑ Hildegard of Bingen. The psychological and social uses of prophecy , FLANAGAN, Sabina Florence (1985): Dissertation University of Adelaide , page 67f, accessed December 9, 2017

- ↑ Religious Thinker , MEWS, Constant (1998): pp. 52–69, essay, in Voice of the living light: Hildegard of Bingen and her world. The psychological and social uses of prophecy , ed .: NEWMANN Barbara, Univ. of California Press, pp. 57f, accessed December 9, 2017

- ↑ Hildegard of Bingen: An Integrated Vision , KING-LENZMEIER, Anne H. (2001): Collegeville, Minnesota, Liturgical Press, p. 48

- ^ Foreword , by FOX, Matthew in HOZESKI, Bruce W. (1985): Hildegard of Bingen's Mystical Visions. Ed .: Clow & B. Clow.

- ↑ Oliver Sacks. Migraine: The Evolution of a Common Disorder . Berkeley: UCLA Press, 1970, p. 57-59. Cited in King-Lenzmeier, pp. 49 and 204.

- ↑ Artist , CAVINESS, Madeline (1998) page 110-124, essay in Voice of the living light: Hildegard of Bingen and her world. The psychological and social uses of prophecy , ed .: NEWMANN Barbara, Univ. of California Press, p. 113, accessed December 9, 2017

- ↑ Kent Kraft (1978): The Eye Sees More Than the Heart Knows: The Visionary Cosmology of Hildegard of Bingen . University Microfilms: PhD. diss. University of Wisconsin-Madison, pp. 97 and 106, cited in King-Lenzmeier (2001): pp. 48 and 204.