Vision literature

The genre of vision literature initially comprises all visionary experiences recorded in writing . These experiences can be religious and non-religious. The texts of the vision literature always coincide with other literary genres, depending on the context in which they were written. Visionary reports can be included in autobiographies, saints' lives, letters, chronicles or medical reports. Many texts, especially those with a political or literary context, cannot be clearly assigned to an actual visionary experience.

In addition to the literatures in which it can be integrated, vision literature belongs as a sub-genre to the areas of legends and revelation literature . The genre legend cannot be clearly defined. The term is often used very differently, it can include everything from the legendary story in the English-speaking area to the liturgical reading and the specific legend of saints in the German-speaking area. The vision literature falls under this designation, since the often instrumentalized texts cover all areas of legends.

In addition to vision reports, the revelation literature also includes reports on auditions , apparitions and raptures and is therefore to be understood as an umbrella term. Their literary forms range from autobiographical recordings of visions, often carefully composed books of revelation and lives of grace , to stylized letters.

The vision literature experienced its heyday in the Middle Ages. Writing down visions was one of the most popular texts in this era, as they could be used as an instrument in addition to their entertainment value. They were used for religious instruction, to decorate sermons and also to support political goals. Despite these diverse uses, there must already have been an awareness in the Middle Ages that it was a separate genre, as evidenced by the collections on this topic.

Individual traditions in vision literature

Antiquity

In antiquity, the genre of vision literature comprised very few texts. Some are known from historiographical literature. Reports of revived people (anabioseis) can already be grasped as a separate genus in ancient Greece. There are also reports of descents into the underworld (Katabaseis). These texts have not survived, but only known from remarks in other ancient texts. Plato reports in the Politeia of the Pamphylian's journey to the hereafter . After his apparent death on the battlefield, he experiences the judgment of the dead with rewards and punishments, as well as the rebirth of souls in other bodies. He wakes up at the stake on which the fallen should be burned. The report is strongly moralizing, so that it is assumed that it is a fictional journey to the hereafter. Plutarch recorded other seasons of death .

Apocalypses and Apocrypha

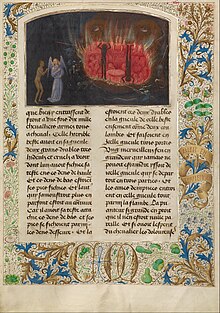

In the period between the 2nd century BC BC and the 3rd century many texts were written that contain descriptions of visions and the places seen in the hereafter. These include apocalyptic texts and visions of the martyrs . The Catholic Church only included the Revelation of John in the biblical canon . Other texts (for example the Apocalypses of Sophonias , Esra and Peter ) are therefore called Apocrypha (from the Greek apokryhpos = hidden, secret), but they continued to circulate within the Church. The Visio Sancti Pauli , which was wrongly attributed to the Apostle Paul, is particularly well known . These apocryphal visions were popular in the Middle Ages and served as models for later texts.

middle Ages

With the Visio Baronti , the genre finds its way into the Middle Ages. This text is the first independent visionary text of this era. The vision of the monk Barontus is said to have occurred on March 25, 678/679 in the Longoretus Monastery (later St-Cyran, Archdiocese of Bourges ). In terms of content, the visions before the 12th century are mainly about punishments or rewards that await the soul in the hereafter. Most visionaries of this era were men who only ever experienced one vision (individual vision). Dinzelbacher puts forward the thesis that far more visions were experienced in the Middle Ages than today. Among other things, he ties this to the sources. In addition to the vision reports, behind which an actual experience is presumed, there are also in the Middle Ages those that were only written to disseminate ideas, including to propagate theological teachings or political goals.

The visionaries are increasingly playing a new role. Since more and more people appear who have several visionary experiences, the visionaries, since they obviously seem to have a special connection to God, can exert influence in religious and worldly matters. After all, a visionary talent for religiously important personalities is almost a prerequisite. In the lives of holy women, which were written between 1300 and 1700, there are almost always reports of visions, apparitions or auditions.

Latin literature

Up until the 12th century, visions were written almost exclusively in Latin. One of the reasons for this is that visionaries and recorders were mostly monks or nuns. Above all, however, only Latin as lingua sacra ( sacred language ) was basically predestined for theological statements . It was a bold undertaking, motivated by the new spirituality of the medieval poverty and women's movement, when Mechthild von Magdeburg dared to write down her visions in the vernacular.

Vernacular literature

Irish offers a particularly rich vernacular literature. With translations of the Latin texts by Gregory the Great and Beda Venerabilis, the first vernacular texts can be found in English towards the end of the 9th century. The first German texts are translations of the Visio Sancti Pauli and the Visio Tnugdali, which were written around 1190. Around 1200 the Visio Sancti Pauli was translated into Old Norse . The vernacular literature in this period is mainly aimed at clergy.

In the late Middle Ages, other texts were translated into German. With compilations of visionary texts, also in example and edification books, the late medieval vision literature also shows literary differences to the previous texts. The use of allegories is increasing, right down to allegorical poetry. An important literary example is the Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri .

Mystical literature

In mysticism , a separate genre developed within the German vision literature. Mystical visions (especially in the form of so-called experiential mysticism ) emerged mainly from the second half of the 13th century. Last but not least, the role model of Bernhard von Clairvaux was influential . It is noticeable that the gender distribution in vision literature is now increasingly changing. While there were more male visionaries up to the 12th century, the number of visions experienced by women predominates in mysticism. In addition, the content of the visions also changes. The previously dominant visions of the otherworldly heavenly regions and places of punishment are replaced by encounters with Christ or saints. Here (in the "Passion Mystic") the Passion of Christ (looking at the wound) and (in the so-called "Bride Mystic") the Holy Virgin play a prominent role.

Decline in interest

Interest in vision literature declined sharply at the end of the Middle Ages. There are several reasons for this:

- Reformed people rejected everything that could not be taken verbatim from the Bible, as well as the veneration of saints and their vites.

- The Fifth Lateran Council placed all "private revelations" under the sole control of the Holy See .

- Humanism and the Enlightenment fought everything that could not be rationally explained.

Modern

Since the 1960s, increased attention has been paid to the topic from a medical-psychological point of view. It is also based on the thesis that the interpretation of what is seen in the vision says something about the culture of the visionary. A well-known visionary of the modern age was Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov (1853-1900), religious philosopher and friend of Dostoyevsky , who was commissioned in a vision to go into the Egyptian desert. More recently, Therese Neumann became known because of her stigmata and Marthe Robin because of her lack of food. In the modern age, skepticism towards visions predominates.

Research history

A complete summary of the vision literature is still missing. Overall, visionary texts are edited less often than other medieval texts. Many texts, especially from high and late medieval vitae, are only available in baroque editions such as B. the Acta Sanctorum available. There is also an imbalance in secondary literature. On the one hand, there are overall fewer studies on vision literature than on other literary genres; on the other hand, studies on vision literature mostly relate to the more well-known visions.

Vision literature and art

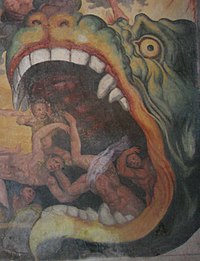

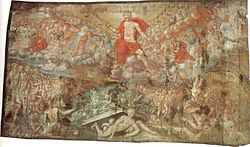

In art, depictions of the afterlife are very popular, especially in the late Middle Ages. The motifs largely correspond to the descriptions of the visionaries, whereby what is seen follows common topoi. In addition to depictions in churches, for example on triptychs , there are numerous book illustrations (e.g. Simon Marmion ) and depictions of the visual arts (e.g. Hieronymus Bosch and Stefan Lochner ).

Content of the visions

In the texts of the vision literature, some topoi and connections appear again and again. This also includes the content that is decisive for the designation of the experience as a vision, such as the rapture into another space, or through space and time. The place seen does not have to be an otherworldly (like heaven, hell etc.), but can also be a completely earthly one.

Due to the frequency of topoi in medieval vision reports, it is often assumed that these are purely literary texts that are not based on actual experiences but on ancient models. On the other hand, it can be argued that many of the descriptions also appear in today's vision reports. It is noticeable that today's visions of religious people are more similar to medieval views than those that were experienced by non-religious people. The mediaeval reports show an abundance of detail that is no longer achieved by modern observations. It is noticeable that modern visions are often described in very abstract terms, whereas medieval descriptions can contain very plastic details. Dinzelbacher also points out, however, that the recorders of the visions in the Middle Ages liked to upgrade their texts with quotations from the Bible and theological literature. Certainly one or the other thing was added that the seer had obviously "forgotten" in his vision or something left out that was not important by their standards. Today, when recording near-death experiences and other visions, emphasis is usually placed on reporting as objective as possible.

A general structure can at least be established for many so-called death visions:

- Separation of body and soul

- Leaving the earthly world, transition mostly between dark and light, e.g. B. through a tunnel

- Entry into the hereafter, which comprises several areas

- Encounters with beings or persons who usually appear in a special light

- Review of your own life

- Desire to be able to stay in the hereafter

- Return to the body

From a medical-psychological point of view, it is not uncommon for the contents of visions to be similar across epochs and cultures, since the physical conditions have not changed. Rather, the content is described and interpreted differently. The descriptions of believers are similar across epochs.

Places viewed

In medieval visions, places of torture (e.g. hell , purgatory ) are more often seen as places of grace. Such places rarely appear in modern visions. This can be traced back to the fact that these places were much more present in art and culture of the Middle Ages than they are today. External influences create expectations that lead the visionary to a certain interpretation of what he has seen. In modern descriptions, especially by non-religious seers, the general skepticism and the abstractness of what is seen stand out.

Places of grace

Paradise often appears in visions in the form of holy Jerusalem according to the Revelation of John. This paradise appears particularly often in visions from the 11th and 12th centuries, but it has also been reported in modern visions.

Places of punishment

- ice desert

- The purgatory as a place of purification is not mentioned in the Bible and is only in the 12th century in the more detailed discussion of the Last Judgment on. In some visions and apparitions, the deceased ask that the living shorten their time in purgatory through good deeds and prayers.

- Fire pit

- The Beyond Bridge has appeared in many variations in the visions since the early Middle Ages. In many cases it acts as a judgment or test bridge for the souls and can also represent the connection between paradisiacal regions and the places of punishment. Not only does it change its appearance (e.g. with nails riddled with it), but also the ground beneath it (e.g. burning river, fire pit, hell, purgatory). In many visions since 9/10 In the 18th century (especially in the Irish sphere of influence) the Beyond Bridge changes its width when crossing, which could indicate Celtic influences. It can also be stated that the hereafter bridge as a motif occurs not only within Christianity, but also in the hereafter conceptions of Iran and Islam.

- A spiked field is also one of the places seen in many visions. In addition, it is often described in such passages that the souls who have done good in their lives are given a pair of shoes to cross this field, the other souls not.

- Soul-eating dragon

Events

Provision of one's own life

Demonic attacks are described in many medieval death reports. Often the demons hold up against the seer his sins. In some visions, angels appear as defenders of the soul. In recent death visions, the viewers sometimes report a kind of "life film" in which their previous life is usually shown in great detail, whereby in some cases their own assessment of the previous way of life comes about. Such experiences are particularly described in the case of visions as a result of accidents.

Punish

In the hereafter, the seer is often shown various places of punishment and the associated punishments. In some cases the seer must also endure punishments himself. In part, the injuries that were inflicted on the visionary's soul in the hereafter were allegedly still visible for some time after the vision. This is also the case with injuries from so-called beatings . They are known to Christian and pagan literature and were also reflected in the folk culture of the 16th and 17th centuries. A Christian example is the beating dream of a monk who was supposed to dissuade his confreres from the luxury of clothing, but after two visions had not been able to bring himself to share what he had seen. The monk received blows from an angel in the third vision, the traces of which are said to have been visible even after the vision. Then he tells the bishop, shows him the wounds and thus gets him to enforce stricter dress codes.

people

Often the soul, separated from the body, is led through the hereafter by a guide - usually an angel or a saint. Encounters with relatives and acquaintances (often the deceased) are reported in modern visions, whereas in medieval visions it is more often religious leading figures. If encounters with relatives are reported, the medieval seer does not seem to ascribe a major role. The number of unguided journeys to the hereafter has increased in modern times.

Consequences from the vision

The visionaries drew conclusions from their experiences. Often they were asked in the vision to tell others about what they saw. In many cases, the visionary then changes his way of life and joins, for example, an order or founding a monastery. Visionary accounts are therefore among the founding legends of many monasteries. In modern visions, an increase in general piety has been noted that is not tied to religious ideas of the church.

Types of vision literature

There are different methods of structuring the vision literature, so only examples can be presented here. The literary approach according to Alessandro D'Ancona offers a clear classification :

- Poetic Visions - A subject is written down in the literary form of a vision without an actual experience having to be the basis.

- Political visions - you deal with a historical event or a person and associate it with a (mostly critical) tendency. These include, among other things, the hike into the hereafter, the gathering of the deceased and visions of judgment. It can be texts with or without a real background. The high point of this genre is probably the Carolingian to Salic epoch.

- Contemplative visions - In terms of content, they relate primarily to edification and repentance, which is why almost all medieval visions can be put into this category. The main themes of this type are the saints of Christ and Mary.

Peter Dinzelbacher distinguishes between two types (with regard to medieval visions):

- Type 1: Fate of the soul in the afterlife, mostly individual experiences, mainly in the early Middle Ages, more men

- Type 2: encounter with Jesus, unio mystica , love , wounds, often several visions, almost exclusively in the high and late Middle Ages

Another method is the theological classification according to Augustine.

Problems of vision literature

One of the main problems with vision literature is third party transmission. The visionary often explains how indescribable the experience was. Abstract terms are therefore particularly often represented in modern descriptions. In the Middle Ages, the actual visionaries were often illiterate and could therefore neither read nor write. Because of this, they mostly had no access to the written culture . The authors who wrote down the vision after it was submitted often had a slightly different social and cultural background. These authors change the vision more or less strongly when they are written. In many cases they make comparisons with biblical or literary models in order to reinforce or explain various aspects of the vision. It is not always clear which parts originally belonged to the vision and which were added later. It is quite possible that individual visions have been changed to such an extent that the original experiences are no longer included. Texts are known from the late Middle Ages that formally resemble a vision report, but cannot be traced back to actual experiences. The visions of Othloh, the "liber visionum" and Gottschalk offer a special exception. The first two visionaries wrote down their views themselves, the "liber visionum" also being handed down in this first author's version. The Gottschalk vision, on the other hand, was recorded in writing by two different authors. The translation into Latin may also have changed the content of what was seen. The skepticism with which one meets visions is also more modern. Nowadays, the church, too, largely distances itself from visions with a religious content. Many visions are dismissed as hallucinations, sometimes by the seer himself. The neurologist Ernst Rodin subsequently distanced himself from his descriptions and dismissed them as toxic psychosis. It is difficult to make a separation here, especially in view of the fact that physical or emotional problem situations often preceded the vision.

In view of these often very intricate ways in which vision literature emerged and received, every statement about the truthfulness of a visionary text requires a thorough analysis with regard to:

- Author (Has the text been written, dictated or edited by the author himself - under which mental or physical circumstances? - Is it editorially revised, possibly with a monastery collective or another interest group in the background?)

- Target audience (who are the direct and indirect addressees? To whom or also against whom are the statements directed?)

- literary genre, motifs and text structure (what is necessary, common or not possible within a certain genre? What are self-imposed, merely adopted or independently processed, adopted motifs? What expressiveness do they have at their respective location within the specific structure of a text? )

- Time situation (Which questions determined the intellectual discourse of the time of writing or reception? How were the respective - including social - conditions for the creation of "vision literature" determined?)

- Reception (which interests and intentions were decisive for the reception of a text?)

- The present aspect (Are the current questions appropriate to the time when a text was written and to what extent are they determined by today's way of thinking and interests?)

In addition to the internal literary problems of the vision literature, there is another point that affects more of the practical side: The manuscripts were not only caused by "normal" causes (fire, water, reuse of parchment etc.) by ignorance or even ideological biases in the age of Enlightenment decimated, since z. B. the Josephinian officials did not appreciate the vision literature and the works were thus sold or even destroyed.

Causes and requirements of the visions

Physical causes

- Ascetic Practices

- Fasting: Othloh has one of his visions at the end of Easter Lent Overall, an accumulation of visions can be observed in the weeks before Easter. If you wanted to hike through the Purgatory Patricii , you had to fast and pray for 14 days.

- lack of sleep

- trance

- Infliction of pain (e.g. with Heinrich Seuse )

- Illness: In laypeople, this trigger is more common than ascetic exercises.

- Near-death experiences: It should be noted here that visions cannot be linked to medical findings or external circumstances (accident, illness, etc.). Overall, most people do not experience a vision in such situations.

- Drugs: Visions induced by drugs are not known from the Middle Ages.

Mental causes

Visions are often viewed as hallucinations in psychology . They can be triggered by crises and conflicts and reflect fears and wishes of the visionary. When examining Otloh's visions, Hedwig Röckelein emphasizes that these are closely related to conflict situations and tensions in his social environment. This is also the case with many other visionaries, but Pope Gregory I already distinguished visions from bad dreams as a result of worries and problems. Often it is no longer possible to decide whether conflicts in the viewer's environment had an impact on the specific content, as this was not reported. In some descriptions, such as Thurkill's vision , the punishment of the soul in the hereafter makes it clear which offense the person in question is guilty of. Hildegard von Bingen , according to her own statements, experienced her visions awake and with open eyes, without ever falling into ecstasy. An examination of medieval vision literature with psychological methods could offer interesting insights into the unconscious feelings of individual medieval people. In a psychological investigation, Frenken tried to work out the biographical aspects of the visions and actions of German mystics and sees traumatic childhood experiences as an important element of such experiences.

Social historical background

In visionary women's literature from the Middle Ages to well into the modern era, questions should not only be asked about religious or psychological backgrounds, but also about sociological ones. When a woman wanted to express herself publicly on questions of theology, politics or social life, she generally had neither chairs nor means of publication at her disposal. Her hearing was only heard as a visionary. There are numerous visions in which self-confident monastery women seize the opportunity to participate in the religious discourse of their time with the help of a pictorial, visionary-dialogical style of conversation in a kind of “narrative theology” and to have an impact on their monastery community as well as on the church and society. In particular, examples of the so-called “experience mysticism” must always be scrutinized critically.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Röckelein describes the resulting problems with regard to the genre of vision literature on p. 14

- ↑ So also in the research literature , summarizing Brigitte Pfeil: Die 'Vision des Tnugdalus' Albers von Windberg. History of literature and piety in the late 12th century. With an edition of the Latin 'Visio Tnugdali' from Clm 22254. (Mikrokosmos, 54) Frankfurt 1999 p. 37ff

- ↑ For example B. obtained from the Visio Tnugdali 172 manuscripts.

- ↑ E.g. the collection Liber visionum von Otloh, cf. Dinzelbacher 1981 p. 1.

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher 1989 p. 8

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher 1989 p. 8f

- ↑ Jacques Le Goff : The Birth of Purgatory. P. 44

- ↑ Dinzelbacher 1989 p. 9f

- ↑ Dinzelbach Medieval Vision Literature

- ↑ Peter Dinzelbacher: Middle Latin literature. In: Lexikon des Mittelalters, Volume 8, Visio (n), - sliteratur .

- ↑ See: Hildegund Keul: Schweige Gottesrede. The mysticism of the beguines Mechthild von Magdeburg. (Innsbrucker theological studies 69) Innsbruck, Vienna 2004, esp. Pp. 156–162.

- ↑ D. Ó Cróinín: Old and Middle Irish literature. In: LexMa 8, Visio (n), - sliteratur .

- ^ P. Dinzelbacher: German literature. In: LexMa 8, Visio (n), - sliteratur .

- ^ Rudolf Simek : Scandinavian literature. In: LexMa 8, Visio (n), - sliteratur .

- ^ P. Dinzelbacher: German literature. In: LexMa 8, Visio (n), - sliteratur .

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher 1989 p. 11f.

- ↑ Peter Dinzelbacher: Medieval vision literature. P. 4

- ↑ Cf. Dinzelbacher 1981 p. 79f.

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 71ff.

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 71f.

- ↑ after Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 74

- ↑ In detail: Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle

- ↑ Dinzelbacher 1989 p. 40

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 76ff.

- ↑ Dinzelbacher 1989 p. 62ff.

- ↑ Jacques Le Goff : The Birth of Purgatory. Stuttgart 1984 ISBN 3-608-93008-6

- ↑ See also Peter Dinzelbacher: The Beyond Bridge in the Middle Ages. Vienna 1973

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 81

- ↑ Cf. Dinzelbacher 1989 p. 39f

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 81

- ↑ As in Gottschalk (stabbed feet, burns, headache) author A, cap. 58-60, Assmann p. 146ff.

- ^ Otloh von St. Emmeram : Liber Visionum . Migne PL 146; 341-388. MGH SS IV p. 888, Addenda

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher 1989 p. 40

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher 1989 p. 48

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 80ff.

- ↑ Peter Dinzelbacher (Ed.): Medieval Visionsliteratur. An anthology. Darmstadt 1989. p. 2

- ↑ Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 89

- ↑ See Röckelein p. 17

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher 1981 p. 1, Röckelein p. 55

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher 1981 p. 1

- ↑ See Röckelein p. 24

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 86

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 92

- ↑ See Dinzelbacher 1981 p. 79

- ↑ Othloh Lib. Vis. cap.3

- ↑ See Röckelein p. 103

- ↑ Owein, Röckelein p. 103, Dinzelbacher p. 67ff.

- ↑ Röckelein p. 103f.

- ↑ Dinzelbacher An der Schwelle p. 90

- ↑ Dinzelbacher 1981 p. 4, Röckelein p. 104 (it points to possible connections between vision and incense), Benz p. 68ff

- ↑ See Vision In: Gero von Wilpert : Subject Dictionary of Literature (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 231). 8th, improved and enlarged edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-520-23108-5 .

- ↑ Röckelein p. 66ff & p. 102 & p. 105

- ↑ Dinzelbacher 1981 p. 30, Pitra, Analecta 33

- ↑ See Röckelein p. 19

- ↑ cf. Ralph Frenken: Childhood and Mysticism in the Middle Ages. (Supplements to Mediaevistik, Volume 2) Frankfurt am Main 2002, p. 20 ff.

- ↑ According to Siegfried Ringler: Vites of grace from southern German women's monasteries of the 14th century - writing vitals as a mystical teaching. In: Dietrich Schmidtke (Ed.): Minnichlichiu gotes discernusse. Studies on the early occidental mystic tradition. (Mysticism in Past and Present I 7) Stuttgart - Bad Cannstatt 1990, p. 89-104, here p. 104 and 96f., With examples from the visions of Christine Ebner p. 95f. and 99-101.

- ↑ See z. B .: Claudia Opitz : Eve daughters and brides of Christ. The female context and culture of women in the Middle Ages. Weinheim 1990, pp. 19-21; 74-78; 102f .; 141-149; esp. pp. 78–83: From hysteria to theology . Basically with: Ursula Peters: Religious experience as literary fact. On the prehistory and genesis of women-mystical texts of the 13th and 14th centuries . (Hermaea NF 56) Tübingen 1988, esp. Pp. 190-194.

literature

- Ernst Benz : The vision. Forms of experience and world of images. Klett-Verlag, Stuttgart 1969 ISBN 978-3-12-900610-8 .

- Peter Dinzelbacher : Vision and vision literature in the Middle Ages. (Monographs on the History of the Middle Ages, Volume 23) Stuttgart 1981.

- Peter Dinzelbacher: On the threshold to the afterlife. Death visions in an intercultural comparison. Freiburg 1989.

- Peter Dinzelbacher: Medieval vision literature. An anthology. Darmstadt 1989.

- Per Dinzelbacher, Hermann JW Vekeman, Rudolf Simek, Reinhard Gleißner, Dáibhi Ó Croínín, Uda Ebel, Dietrich Briesemeister: Visio (s), -sliteratur . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 8, LexMA-Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-89659-908-9 , Sp. 1734-1747.

- Ralph Frenken: Childhood and Mysticism in the Middle Ages. (Supplements to Mediaevistik, Volume 2) Frankfurt am Main 2002.

- Hedwig Röckelein : Otloh, Gottschalk, Tnugdal: Individual and collective vision patterns of the High Middle Ages. (European university publications. Series III. History and auxiliary sciences, Volume 319) Dissertation Tübingen. Frankfurt am Main 1987.

- Wilhelm Schmitz / Julius Schwietering : Dream and Vision in the Narrative Poetry of the German Middle Ages. (Research on the German language and poetry, volume 5) Münster 1934.

- Max Voigt: Contributions to the history of vision literature in the Middle Ages. (Palaestra: Studies and Texts from German and English Philology, 146) 2 volumes, Leipzig 1924.

See also

Web links

- Database on Dreams and Vision in Antiquity

- Hell-On-Line, information portal on visions of the afterlife , supervised by Eileen Gardiner (engl.)