Hieronymus Bosch

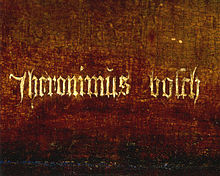

Hieronymus Bosch [ ɦijeːɾoːnimʏs bɔs ] (born Jheronimus van Aken [ jeɪɾoːnimʏs vɑn aːkə (s) ] * in 1450 in 's-Hertogenbosch , † August 1516 ) was a Dutch painter of the Renaissance . Bosch came from a family of painters. He often had his clients in the higher nobility and clergy . His paintings, mostly in oil on oak, usually show religious motifs and themes. They are rich in figures, mythical creatures and unusual pictorial elements, the context and interpretation of which are often not certain. Bosch's work receives regular attention to this day and it has been widely received in art. There are few reliable clues about his life.

Origin and name

Hieronymus Bosch came from the “van Aken” family of painters, whose name of origin indicates that the direct ancestors in the paternal line came from Aachen . Four generations of painters are proven: Hieronymus Bosch's great-grandfather Thomas van Aken worked as a painter in Nijmegen . His grandfather Jan van Aken moved from Nijmegen to the up-and-coming town of 's-Hertogenbosch around 1426. He crowned his social advancement in 1462 with the purchase of a stone house directly on the market square, to which he also relocated his painting workshop. Four of Jan's five sons, including Hieronymus' father Anthonius van Aken, also became painters. Anthonius had five children: two daughters (one was called Herberta) and the three sons: Goeswinus or Goessen van Aken, Jan van Aken and, as the fifth child, Jheronimus van Aken (Hieronymus).

Hieronymus later named himself after his hometown, which is also called Den Bosch . In Spain, where some of his most important paintings are exhibited in the Museo del Prado , it is called El Bosco .

Life

Like his two older brothers, Jerome followed the family tradition and, like them, received his training as a painter, at least for a time in his father's workshop. After the death of his father, Goessen continued the workshop as the oldest son.

Hieronymus Bosch was first mentioned in a document in 1474. In 1481 he married the patrician daughter Aleyt Goyaert van de Mervenne, who brought a house and an estate into the marriage. This helped Bosch to achieve greater independence.

In 1488 he joined the religious brotherhood of Our Lady of the local St. John's Cathedral , first as an external member, then as a sworn member. The elitist inner circle of the brotherhood comprised around 60 people, who as a rule came from the highest aristocratic or patrician urban class and almost all of them were clergy with various degrees of ordination. Almost half were secular priests, some of whom were also notaries. There were also doctors and pharmacists among them, as well as a few artists: musicians, an architect and only one painter - Hieronymus Bosch. The brotherhood maintained contact with the highest circles of the nobility, the clergy and the urban elite in the Netherlands. In addition to this political and social side, they were equally religious and were looked after by the Dominicans . They met once a month for dinner and twice a week for mass. St. John, Mary and other feast days were celebrated through spiritual games and processions. Bosch found his clients in the ranks of the brothers and through their contacts with the nobility.

In addition to the Liebfrauenbruderschaft, he worked for the urban elite and the Dutch nobility. Among his most important clients were the ruling Prince of the Netherlands Archduke Philip the Fair and his court.

Bosch died in his hometown in 1516 at the age of 66.

plant

Painting style, themes

Hieronymus Bosch lived in the age of the Renaissance , a period of economic awakening, princely power politics and the demand for religious and moral renewal. In his pictures he subjected all classes to criticism, not just the clergy . Bosch often painted religious motifs and themes. Triptychs like The Hay Wagon and The Garden of Earthly Delights , on the other hand, were clearly not intended for an altar , but rather to impress and entertain a courtly audience.

His work eludes a simple interpretation: while there are some plausible interpretations of his works, many representations have remained puzzling or the interpretation is controversial. Bosch himself did not leave any written records of his works.

Bosch mostly painted with oil paints, rarely with tempera , on oak wood. His palette was not very rich in many pictures. He used azurite for the sky and landscapes in the background, green glazes and pigments containing copper ( malachite and copper (II) acetate (verdigris)) for foliage and landscapes in the foreground and tin-lead yellow , ocher and red lacquer ( carmine or madder ) for the important ones Image elements a.

Most of Bosch's works have been preserved in the form of paintings on wooden panels, as well as a few drawings on paper.

Attributions

In the past, paintings were on the one hand newly assigned to Hieronymus Bosch, while others were no longer assigned to him due to more recent findings. Assessments have often been controversial.

In preparation for a comprehensive Bosch exhibition in Rotterdam in 2001, Prof. Peter Klein (University of Hamburg) examined the oak boards used by Bosch and his workshop as a painting surface using the analysis method of dendrochronology . As a result, some of the works previously attributed to Bosch had to be removed from the overall works, such as The Wedding at Cana . The panels are made of wood from trees, some of which were felled decades after Bosch's death.

As part of the preparations for the big Bosch anniversary exhibition on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of his death in the spring of 2016 in the Noordbrabants Museum in 's Hertogenbosch , the Bosch Research and Conservation Project (BRCP) rated 21 paintings and 20 drawings as handwritten. According to the catalog raisonné from 2016, The Juggler (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Musée municipal), The Stone Cutting and The Seven Deadly Sins are no longer attributed to Bosch.

Recurring image elements

Symbols

Hieronymus Bosch repeatedly used the same symbols in many of his pictures , the meaning of which has been passed down today partly through texts, partly through comparing his works with others. There is a multitude of partly very extensive philological and art-historical studies on this symbolism or iconography .

- The bear stands for the deadly sin "anger".

- The toad - it is mostly perched on a person - stands for "depravity". If she crouches on the genitals, this is seen as an allusion to the mortal sin " lust "; if she crouches on the chest or face, this can also be an allusion to the mortal sin "arrogance" (arrogance, conceit).

- The funnel, mostly turned upside down on a person's head, stands for “meanness, deceitful intent” (the person carrying the funnel has shielded himself from heaven, the eye of God).

- The arrow also signals evil , sometimes it sticks across the hat or cap, sometimes it pierces the body, sometimes it sticks in the anus of a half-naked person (which is also an allusion to "depravity").

- The jug is often combined with a stick, sometimes it is skewered directly on it. It is a sexual innuendo that indicates “lust”.

- The same applies to the barrel with the bung , which is often found in combination with a stick.

- The bagpipe is also an allusion to the deadly sin "lust".

- The owl can not be interpreted in antique mythological meaning as a symbol of wisdom in Christian images. Bosch has placed the owl in many pictures, sometimes placing it in the context of people who behave insidiously or have fallen victim to a mortal sin. That is why it is often assumed that as a nocturnal animal and bird of prey it stands for evil and symbolizes folly, spiritual blindness and the ruthlessness of everything earthly.

- The interpretation of symbols depends very much on their respective pictorial context , so that a positive symbol like the swan , which in connection with Mary means purity and chastity, can mean the opposite in other pictorial contexts. It adorns a house on a flag that is clearly identified as a brothel by other symbols .

Demons and mythical creatures

Demonic figures and mythical creatures are incorporated into many of Bosch's pictures . There are also human beings with animal heads of fish , birds , pigs or predators , ugly gnomes and monsters populate the pictures. They torment defenseless people or lead them to be condemned.

The depiction of mythical creatures was not unusual in the Middle Ages, it appeared in the so-called bestiaries . The bestiary developed from the Physiologus , a mythological “animal science book” from Alexandria ( Egypt ), which found its way to Europe in the early Middle Ages and was translated. Bestiaries are allegorical animal books that describe real and fantastic animals and try to typologically emphasize their actual or supposed peculiarities. They served as didactic media for teachings in morality and religion and were very popular because people could only get to know exotic animals from other continents through these books. But mythical animals like the unicorn or the dragon also found their way into such works.

Some of his pictures reflect that Bosch knew and valued bestiaries. Real animals, known in Europe or from exotic habitats, keep appearing there. The further development from mythical creatures to terrifying creatures is largely due to Bosch. He wanted to make the evil visible in people.

He also took up the traditions of the marginalia from the book illumination of his time, which knew mythical creatures, but also other topics such as the topos of the " upside-down world " or pure ornamentation.

The mysterious face

In the mass pictures such as the Garden of Earthly Delights , the facial features are greatly simplified or caricature-like. However, there are also precise, naturalistic depictions of the face, which are characteristic of a Renaissance painter . In some pictures and triptychs a face appears again and again: it can be seen on the octagonal panel in Rotterdam The Wanderer (also called The Tramp ) and The Prodigal Son / The Pilgrim on the outer wing of the hay cart triptych in Madrid. Similarities are found between this and the face of the "tree man" (triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights ). The image reflects an even face shape with a long nose. The look seems thoughtful, serene. On the left wing of the triptych The Temptation of St. Anthony (next to two monks) a secularly dressed person helps Antony over a bridge - it is the same face, only a little older. And finally: In the painting John on Patmos sits next to the saint a lizard-like animal, and this, like a small winged demon at the bottom of the picture Death of a Miser , bears the facial features described.

Some suspect a self-portrayal of Hieronymus Bosch, others a client. Wilhelm Fraenger saw here and in numerous similar recurring portraits in pictures by Bosch the Jew Jacop van Almaengin, who had converted in 1496 and who was something like patron and grand master of Bosch's lodge in s'Hertogenbosch, the painter's intellectual role model and client. The latter assumption seems unlikely because of the negative impression caused by the combination of the face with monster-like body parts, for example in the case of Johannes on Patmos .

There is only one single, often copied, “portrait” of Hieronymus Bosch, a posthumous drawing from around 1550 with an unexplained origin and authenticity. His facial features shown there do not correspond to the person he so often painted. Marijnis / Ruyffelaere write: “Obviously it was Hannema ( De Verloren Zoon van Jheronymus Bosch , Jaarsverlag Museum Boymans, 1931) who introduced the hypothesis that the person could be a self-portrait of Bosch. Some authors speak of a spiritual self-portrait ”.

reception

painting

Northern Mannerism painters Jan Wellens de Cock (around 1475 / 80–1527 / 28), Jan Mandyn (around 1500–1560), Herri met de Bles (around 1500 / 10–1555 / 60) and Pieter Huys (around 1519 / 20–1581 / 84) are assigned to a group of Dutch / Flemish painters who continued the tradition of Hieronymus Bosch and his fantastic painting, especially his Antonius experiments.

The influence of Bosch on modern surrealism was rejected by Salvador Dalí . According to Dalí, "Bosch's monsters [...] are a product of the fog-shrouded north and the terrible digestive disorders of the Middle Ages. The result is symbolic characters, and satire has taken advantage of this gigantic diarrhea. I am not interested in this universe. We have here the exact opposite of monsters that are born differently and, in contrast, live on an excess of Mediterranean light. "

Other genres

- literature

- Nelly Sachs wrote a poem called Hieronymus Bosch . It can be found in the volume Fahrt ins Staublose (1961) in the cycle Dornengekrönt .

- In Arno Schmidt's dialogue novel Abend mit Goldrand (1975) The Garden of Earthly Delights is the main work of art that is often and ambiguously referenced.

- music

- The composer Horst Lohse wrote a triptych for the Madrid table : The seven deadly sins (1989) - The four last things (1996/97) - Cave cave Dominus videt (2011/12).

- dance

- The Garden of Earthly Delights was choreographed by Blanca Li ( Le jardin des délices , Festival Montpellier Danse 2009).

- Movie

- In the movie In Bruges ... and die? (2008) by Martin McDonagh alludes to The Last Judgment by Bosch. In the Bosch series , the main character is called Hieronymus "Harry" Bosch.

literature

- Collective of authors: Hieronymus Bosch . "Great Masters" series. Karl-Müller-Verlag, Erlangen, 1993.

- Catharina Barker: The Garden of Heavenly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch in the light of Christian Rosenkreutz's teachings. Volume 1: Life in Religion, Tradition and Philosophy , ISBN 978-3-923302-35-2 . Volume II: The Evolution of Personality , ISBN 978-3-923302-36-9 . Achamoth Verlag, Taisersdorf am Bodensee, 2012/13. [speculative-esoteric interpretation of Bosch; no [art] historical interpretation]

- Hans Belting: Hieronymus Bosch. Garden of Earthly Delights . Prestel-Verlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7913-2644-9 .

- Bruno Blondé and Hans Vlieghe: The social Statue of Hieronymus Bosch. In: The Burlington Magazine 131, 1989, pp. 699f.

- Hieronymus Bosch: The Garden of Earthly Delights . Prestel-Verlag, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-7913-2662-7 .

- Hieronymus Bosch: Lost in Paradise . In: du , 750 issue 10, Oct. 2004; Niggli, Zurich, ISBN 3-03717-008-5 .

- Nils Büttner : Hieronymus Bosch . Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-63336-2 .

- Jacques Combe: Hieronymus Bosch . Verlag F. Bruckmann, Munich, publisher number 1330.

- Godfried CM van Dijck: De Bossche optimaten: divorced van de Illustere Lieve Vrouwebroederschap te's-Hertogenbosch (= Bijdragen tot de divorced van het Zuiden van Nederland 27). Tilburg 1973. [Investigation into Bosch's living environment]

- Godfried CM van Dijck: Op zoek naar Jheronimus van Aken alias Bosch: De feiten . Zaltbommel 2001. [Investigation of Bosch's living environment based on documents a. a.]

- Oskar Eisenmann: Bosch, Hieronymus . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 3, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1876, p. 184. (outdated)

- Stefan Fischer: “The Garden of Earthly Delights” by Hieronymus Bosch. Approaches and methods of research . 2001/2007, ISBN 978-3-638-70228-7 or ISBN 978-3-638-28448-6 .

- Stefan Fischer: Hieronymus Bosch: Painting as a vision, teaching image and work of art (= Atlas. Bonn Contributions to Art History NF 6). Cologne 2009 (Diss. University of Bonn), ISBN 978-3-412-20296-5 .

- Stefan Fischer: Hieronymus Bosch. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 27, Bautz, Nordhausen 2007, ISBN 978-3-88309-393-2 , Sp. 161-172.

- Stefan Fischer: Hieronymus Bosch. The complete work . Taschen, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-8365-2628-9 .

- Stefan Fischer: In the maze of images. The world of Hieronymus Bosch. Reclam, Stuttgart 2016, ISBN 978-3-15-011003-4 .

- Wilhelm Fraenger : Bosch . Verlag der Kunst Dresden, 1975

- Jos Koldeweij, Paul Vandenbroeck, Bernard Vermet: Hieronymus Bosch. The complete work . Belser-Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-7630-2390-9 .

- Jos Koldeweij, Bernard Vermet, Barbera van Kooij: Hieronymus Bosch. New Insights Into His Life and Work . NAi Publishers, Rotterdam 2001, ISBN 90-5662-214-5 .

- Roger H. Marijhaben, Peter Ruyffelaere: Hieronymus Bosch. The complete work . Parkland-Verlag, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-88059-971-8 .

- Charles de Tolnay : Hieronymus Bosch . Holle-Verlag, Baden-Baden 1973.

- Rosemarie Schuder: Hieronymus Bosch . Union-Verlag, Berlin 1975.

- Larry Silver: Hieronymus Bosch . Hirmer-Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-7774-3135-2 .

- Gerd Unverfetern: Hieronymus Bosch. Studies on its reception in the 16th century . Berlin 1980 (Diss. Göttingen 1974).

- Gerd Unverfecht: Wine instead of water. Eating and drinking at Jheronimus Bosch . Goettingen 2003.

- John Vermeulen: The Garden of Earthly Delights. Novel about the life of Hieronymus Bosch . From the Dutch by Hanni Ehlers . Diogenes, Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-257-23383-3 . [strongly distorting biographical and general historical]

Movie

- Hieronymus Bosch - Touched by the devil. Documentary, Netherlands, 2016, 59:14 min., Script and director: Pieter van Huijstee, production: Pieter van Huijstee Film, NTR , German first broadcast: August 21, 2016 on arte , summary by arte.

Web links

Exhibitions

- s'Hertogenbosch, Het Noordbrabants Museum February 13 to May 8, 2016

- Madrid, Prado : Bosch. The Centenary Exhibition , May 31 to September 11, 2016 (largest exhibition to date)

painting

- 48 images. In: Arno-Schmidt reference library of the GASL (PDF; 10.6 MB)

- Research and Conservation Project: Bosch's works in Venice , high resolution and each with X-ray and IRR images (infrared reflectography)

- Pictures of Bosch with comments (Engl.)

- Works by Hieronymus Bosch at Zeno.org .

- Works by Hieronymus Bosch - TerminArtors.com ( Memento from August 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- Web Gallery of Art

- Hieronymus Bosch - a collection of resources and illustrated pigment analyzes of pictures by the artist. In: ColourLex

literature

- Literature by and about Hieronymus Bosch in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Hieronymus Bosch in the German Digital Library

- Paul Vandenbroek: About more recent Bosch literature. (PDF; 17 pp., 10.2 MB)

- Stefan Fischer: Connoisseurship with Hieronymus Bosch. In: Art History. Open Peer Reviewed Journal , 2013 ( urn: nun: de: bvb: 355-kuge-337-1 )

- Erwin Pokorny: Hieronymus Bosch and the paradise of lust. In: FrühNewzeit-Info , (PDF; 13 S., 10.2 MB)

- Erwin Pokorny: Witches and Magicians in the Work of Hieronymus Bosch. In: Lexicon for the history of the witch hunt / Historicum.net , January 23, 2009

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stefan Fischer: In the maze of images . The world of Hieronymus Bosch. Reclam, Munich 2016, p. 7-8 .

- ↑ Luuk Hoogstede, Ron Spronk, Matthijs Ilsink, Robert G. Erdmann, Jos Koldeweij, Rik Klein Gotink, Hieronymus Bosch, Painter and Draughtsman: Technical Studies , Yale University Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0-300-22014-8 .

- ^ Hieronymus Bosch Resources. In: ColourLex

- ↑ See Bosch Research and Conservation Project (BRCP): Jheronimus Bosch - Visions of genius ( Memento from August 21, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; English). The number of 24 paintings given there refers to the fact that the triptych with catalog number 19 was in four parts in four different locations (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam; Louvre, Paris; Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven; National Gallery of Art, Washington) has come down to us.

- ^ Wilhelm Fraenger : Bosch , Verlag der Kunst, Dresden 1975, p. 137ff, Fraenger's entire work is based on it, see the index under Almaengin.

- ↑ Marijnissen / Ruyffelaere: Hieronymus Bosch , Antwerp, 2002, p 412

- ↑ Quoted from Conroy Maddox, Dalí , 1985

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bosch, Hieronymus |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Aken, Hieronymus van; Aken, Jeroen van; Bosch, Jheronimus; El Bosco; Aken, Jheronimus van |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Dutch painter and draftsman |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1450 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | 's-Hertogenbosch , Duchy of Brabant, then part of the Netherlands |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 1516 |

| Place of death | 's-Hertogenbosch |