Christian mysticism

The term Christian mysticism is a collective term for texts, authors and groups within Christianity to which, in retrospect, the religious-scientific category “ mysticism ” can be applied. However, different definitions of the concept of mysticism are proposed. The attribution to "Christian mysticism" depends on this definition as well as on the interpretation of the corresponding primary texts . Both are often controversial. A typical minimum definition understands mysticism as a practice that aims at a unity ( unio mystica ) with God , which should already be partially experienced in this life, as well as elements of a theory that should explain and determine the possibility of such an experience. So the “awareness of God's immediate presence” is proposed as a common frame of reference for the different teachings of the occidental-Christian mystics and the “transformation into God” is determined as the goal of the mystical path. Not only in Catholic theology there is no uniform concept of mysticism, which is related to the fact that the meaning of the word has changed in the course of history.

History of ideas

Biblical origin

The noun form of the word mysticism only emerged in the 17th century ; the adjective 'mystical' in early theologians refers to the inner, hidden, or spiritual meaning of the Bible as revelation, which at the same time remains a mystery . In the New Testament “mystery” means God's hidden eternal plan of salvation for his creation, which he fulfilled in the incarnation , death and resurrection of his Son (1 Cor 2: 7; Eph 1: 9–11; 3: 4–9; 5 , 32f; Col 1,26f). From the Greek “mysterion”, the Latin “sacramentum” developed in Christian theology, meaning the three sacraments of initiation: Baptism , Confirmation and Eucharist . “For ancient people, a mysterion was a type of knowledge that had to be introduced through initiation. There are some things that can only be known if you experience them; any deeper spiritual or psychological understanding belongs in this area. For this reason the word mysterion is very important in the New Testament. "

Words like mysticism, mystery or middle begin with the prefix My- or Mi-, which is in contrast to the prefix Ma- in words like matter, mater or manifestation. If the latter means the visible and tangible reality of the physical, the former refers to the hidden, invisible and intellectually incomprehensible reality of the spiritual or divine, that is, of the One . The "center of Christian mysticism" is one with God or his dwelling in the human heart (see below).

The biblical revelation, inspired by God's Spirit , is understood in Catholic and Orthodox Christianity according to the twofold sense of scripture: Just as the human being is a compound of body and soul, so scripture can be read according to its external and internal sense. This inner sense is again subdivided into threefold: the typological (past), the moral (present) and the anagogical , or eschatological sense (future) leading up to 'heaven', so that as in Jewish mysticism (see PaRDeS ) also from fourfold sense of writing is spoken. According to Cardinal Walter Kasper , theological dogmatics wants to be “a spiritual interpretation of Scripture” which aims “to make the Christ event present again and again in the Holy Spirit in order to bring it to effect on us. The spiritual understanding of Scripture therefore aims to lead into the concrete following of Christ. This opens the christological [= typological] sense to the moral one that moral theology has to interpret. He also opens up to eschatological perfection and our way there. This is where the now neglected disciplines of ascetics and mysticism and the doctrine of Christian spirituality have their genuine place. "

For a mystical understanding of Scripture , the anagogical sense that strengthens hope (Hebrew sod = mystery) is of decisive importance: The orientation towards the ultimate goal of unity with God does not remain a mere future, but is always already in the hope carried by the Spirit as Presence of the hoped for effective. The three theological virtues of faith, hope and love, mediated through baptism, confirmation and the Eucharist, are the sacramental basis of Christianity in general, which in Christian mysticism is not exceeded, but intensified or revitalized. The core point is the fullness and the "unfathomable riches of Christ" (Eph 3: 8), his grace (Eph 1, 7; John 1:16) and glory (Eph 1:18; John 1:14) as well as his word (Col 3:16) or “to measure the length and breadth, the height and depth and to understand the love of Christ, which exceeds all knowledge” (Eph 3:18f).

Mystical sense of the scriptures

The consideration of Holy Scripture according to its inner, spiritual or mystical meaning has its basis in the idea of the concealment of the Spirit of Scripture in its (physical) 'letters': “To this day the cover lies on your (the Jews) heart, if Moses (= the Torah) is read aloud. But as soon as one turns to the Lord, the cover is removed. But the Lord is the Spirit; and where the Spirit of the Lord works, there is freedom. With our faces revealed, we all reflect the glory of the Lord and are thus transformed into his own image… ”(2 Cor 3: 15-18; cf. 3: 6). This process of metamorphosis , as it is represented in the transfiguration (Greek metamorphosis ) of Christ (Matt. 17: 1-9), signifies the equation with the Son of God (Rom. 8:29) as the restoration of man's original image of God “in holiness and righteousness “(Eph 4:24). In other words: the “rebirth” or “God's birth” in the soul or in the heart aims at the undisguised “vision” of God (Theoria), in the broader sense at a mystical “being kindled” by the divine beauty and glory of God and his inexhaustible word. In the story of the Emmaus disciples, to whom the risen One opens their eyes to the inner meaning of Scripture when they 'break bread' and therefore then during the celebration of the Eucharist, the moment of 'being kindled' is most clearly expressed in love: “Burned we do not have our hearts in our chests when he spoke to us on the way and opened up the meaning of the Scriptures to us ”(Lk 24:32).

According to Lk 12.49, Jesus, like a new Prometheus, “came to throw fire on the earth”, which then happens with the sending of the Spirit in tongues of fire at Pentecost (Acts 2,3). Just as the Eucharist is “fire and spirit” ( Ephraem the Syrians ) and “burning bread” ( Teilhard de Chardin ), so, according to Jewish mysticism, “the fiery organism of the Torah” becomes its outer garment with the coming of the Messiah (the letters Sheath of the external sense of writing) and shine as "white fire" or "primordial light": as "light from inexhaustible light".

This trail of fire of the spirit pervades the whole Bible, starting with the burning but not burning thorn bush as a mystical place of the revelation of the name of God (see below) over the pillar of fire as a sign of the way of Israel through the 'desert' (Ex 13: 21f; Ps 78 14) up to the legislation on Sinai in the fire (Ex 19.18; 24.17) and the altar offering consumed by the fire of God (Lev 10.2; 2 Kings 1:10). The everlasting altar fire in the tabernacle and temple is kindled from heaven (Lev 9:24; 2 Chr 7: 1-3). The God, whose word burns like fire (Jer 5:14; 23:29) and who is himself “consuming fire” (Dtn 4,24; Heb 12,29), speaks from the flame to his people (Dtn 5,4f .22-26). Origen (185-254), who, according to the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria, is considered to be the real founder of the spiritual interpretation of Scripture, says of this God who really 'devours' sin : "The fire god consumes human guilt, he eats it up, he devours it, he burns them out, as he says elsewhere: 'I will purify you in the fire until you are clean.' This, then, means the sin-eating of the One who offers the sin offering. Because ' he took our sins upon himself' and devoured and consumed them like fire. "

In the scene of the three young men in the fiery furnace (Dan 3, 15-97), who praised the flames “like a cooling breeze” (Dan 3, 50), the early Christians recognized their own situation of persecution, but also their hope of resurrection, which is why the scene can also be found as a pictorial symbol in the Roman catacombs.

Extra-Biblical Influences

In addition to biblical revelation, extra-biblical influences also play a role in Christian mysticism, especially the terms and teachings of Neoplatonism . The incomprehensibility of God for the discursive mind is emphasized in both ways of thinking and leads to a theologia negativa that does not exist in the Bible. The goal of the Neo-Platonic influenced mysticism was the theoria (θεορία), the "God show".

In this context, the unknown Syrian monk Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita (around 500) coined the term “mystical theology”. According to him, the mystical union (Greek Henosis ) with “the one who is beyond all things” is the goal of the 'ascent' from the material to the spiritual, namely on the threefold path of purification of memory (conscience), of enlightenment of the mind and the union of the will with the divine will ( via purgativa, illuminativa and unitiva ). These three paths are “not as clearly delimited as it may seem. Dionysius does not use this trinity as if moral purification and unifying perfection were clearly distinct from the middle power of knowing enlightenment. (...) The enlightenment already affects the literal sense of the illuminating vision of the sacred symbols (...). Perfection does not mean perfect unity, but perfect knowledge ... "

Mysticism in the Middle Ages of the West

The centers of mysticism in the Latin Church were the monasteries. The monastic mysticism developed as a contradiction to the scientific rationality that was practiced at the newly founded universities in (scholastic) theology. "Fides piorum credit, non discutit" (Faith trusts the pious, it does not discuss), says Bernhard von Clairvaux against dialectical theology. The highest goal remains the unio mystica , the mystical love union with God, a “feeling of God” or in a broader sense “an awareness of the immediate presence of God” (Bernard McGinn).

A large part of the high medieval literature on mystical theology consists of commentaries on the work of the pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita, mediated by Johannes Scotus Eriugena (9th century): “The theology of the Areopagite is a millennium long and even longer than one of the archetypal forms of ecclesiastical theology has been viewed and evaluated. ”Fundamentally, two interpretative traditions can be distinguished in medieval mysticism: a more affective mystical theology (represented by Hugo von St. Victor and Robert Grosseteste , among others ) and a more intellectual one (represented by Meister Eckhart and Cardinal Nikolaus von Kues ). In the more affective tradition, “feeling [God] is also erotically charged and the knowledge of God is interpreted as an encounter between I and God in the sense of a 'holy marriage' between soul and God or Christ” (see motifs below).

The new mendicant orders of the Franciscans and Dominicans open up the path of mystical knowledge of God beyond the old monastic way of life. David von Augsburg , a Franciscan of the first generation, but then above all Bonaventure , the 'prince among all mystics' , becomes significant for mysticism . With him the spirituality of Augustine and Ps.-Dionysius, the Victorians and the Cistercians (Bernhard von Clairvaux) flow together. The 7th General Minister of the Franciscans understands mysticism as an 'experimental' knowledge of God that can be experienced with the five (spiritual) senses ( cognitio Dei quasi experimentalis ), which is differentiated from a doctrinal theoretical knowledge of God ( cognitio dei doctrinalis ). Contemplatio is the most widely used term in the Middle Ages when it comes to mysticism.

War in the 12th century with the Benedictine nun Hildegard von Bingen first came a woman as a mystic in appearance, the experienced woman mysticism in the beguines (like Hadewijch or Marguerite Porete ) and in the Cistercian convent of Helfta ( Mechthild of Magdeburg , Mechtilde , Gertrude of Helfta ) a heyday that continues in the mysticism of the Dominican Catherine of Siena or the hermit Juliana of Norwich .

In the works of the Dominican masters Eckhart , Johannes Tauler and Heinrich Seuse , medieval mysticism reached its climax in so-called German mysticism .

Mysticism in the modern age

In the 16th century, the Spanish mysticism of Ignatius of Loyola , the founder of the Jesuit order ("Finding God in all things"), as well as of Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross of the Carmelite Order, moved into the center of development. "The mysticism of John of the Cross is based on a salvation drama of the marriage: the love movement comes from God, who does not want to be alone, creates humanity as the bride of the Son and repeatedly woos her - up to the incarnation and surrender of his own life" at the cross. “From the outset, creation is related to an intimate belonging to God, it is a gift to the Son and a gift for the sake of the Son, not the work of an almighty being turned away from the world as in deism. The son is the one who makes creation godly through his marriage. The Incarnation is ultimately understood as a redeeming marriage and a ' wonderful exchange ' between the son and the bride, whereby, as in the Trinity, an equalization of the beloved takes place. This configuration is the sign of perfect love. "

With John of the Cross “it says in the Cántico Espiritual: When the soul is united to God, it experiences everything as God, as happened to the Evangelist John ... (...). One must not detach these pantheistic-sounding sentences in Johannes from his poetry - but one must not devalue them as allegorical exaggeration either. In them ... 'the symbol that surpasses allegory in depth' becomes effective. "

The mystical path to the knowledge of God found little echo in the Reformation . Martin Luther himself maintained an ambivalent relationship to mystical experience, and he even called some circles deviating from his line of enthusiasm . Nevertheless, inner-Protestant movements such as Pietism ( Gerhard Tersteegen ) developed again and again , whose religiosity included the mystical dimension. This traditionally emphasized mystic-critical to mystic-hostile attitude of Protestant theology only began to change in the second half of the 20th century. Among the so-called spiritualists , the Görlitz shoemaker Jakob Böhme stands out, in the baroque period the theologian and priest Angelus Silesius (Johannes Scheffler) who converted from Protestantism to Catholicism .

Other representatives of the Baroque mysticism of the 16th century are Valentin Weigel and Johann Arndt .

The Munich doctor, mining engineer, philosopher and 'lay theologian' Franz von Baader , who (before Sören Kierkegaard ) emphasizes the close connection between theological speculation and the simultaneity with the biblical revelation event, is regarded as a 'Boehme redivivus' :' Speculative thinking bridges the gap which exist for non-speculative thinking between the past and the present, just as it bridges the gap that lies between higher life and the supernatural on the one hand and human life and the natural on the other (see also the biblical term life in abundance ). Both times the higher is 'mirrored' into the lower and the lower into the higher. ”“ The separation of speculative and mystical thinking leads to a mystification of mysticism on the one hand and to a flattening of speculation on the other. ”

While mysticism in the Middle Ages emphasized the supernatural reality of the mystical encounter with the divine, in the 19th century emphasis was placed on the fact that the mystical experiences could be demonstrated materially (e.g. in stigmatization , the “heavenly fragrance”). The hereafter should be realized in this world.

In 1966, the Jesuit Karl Rahner formulated the much-quoted sentence: "The pious of tomorrow will be a mystic, someone who has experienced something, or he will no longer be." Rahner emphasizes the experiential dimension of the knowledge of God of the Christian faith as a gift of grace from the saint Mind off. Of this spirit, the letter to the Ephesians (1:18) says: "He will enlighten the eyes of your heart, that you may understand the hope to which you are called through him (Christ)." Christian faith refers to the biblical revelation of the word of God, that as the eternal “word of life” (1 Jn 1,1) gives participation in divine life: “To partake in the life of God, the Trinity of love, is indeed 'perfect joy' (cf. 1 Jn 1,4). "

The Meditation Church Center for Christian Meditation and Spirituality of the Diocese of Limburg , which was new in its kind in Germany in 2007, is also concerned with the importance of Christian mysticism in the present day in a series of events that focus on topics of Christian mysticism, such as female images of God or the image of God Transformation .

Mysticism in the Orthodox Churches

Mysticism has a long tradition in the Orthodox churches . In the monastic movement Hesychasmus (from Greek - ancient Greek : ἡσυχία [f.] Hēsychía , ησυχία [f.] Hesychía = "calm", "silence") the mysticism is practiced through the Jesus prayer (also called heart prayer ) and the navel gaze . The icons occupy a central place as mediators between God and man.

Mysticism and religions

The mystical experience of unity is often ascribed the potential to relativize denominational and religious boundaries. “In the area of Christian mysticism, denominational boundaries are no longer valid.” The thesis that all religions are ultimately one on the mystical level is, however, from the Christian side the need to 'differentiate between spirits' (cf. 1 Jn 4: 1; 1 Cor 12 , 10; 1 Thess 5:21). The situation is different in the dialogue with the directly 'related' religion of Judaism , where Jewish mysticism (see mysticism ), especially in the tradition of Kabbalah, certainly opens up ways to overcome the 'primal schism'.

Motifs of Christian mysticism

Mysticism of God's habitation

One of the main motifs of Christian mysticism is named with the heart kindled by the fire of the love of God, as it is then particularly characteristic of the depiction of Augustine in Christian iconography . The incarnation of the eternal Word of God in Christ, which, according to the Church Fathers, has its first analogy in the idea of the revelation of the word in the '(body) garment' of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, continues in the indwelling of Christ in the believing heart (Eph 3.17). For the community he founded on his missionary journeys in Galatia, Paul suffers “new birth pangs until Christ takes shape in you” (Gal 4:19). He himself can say of himself: “I was crucified with Christ; I no longer live, but Christ lives in me ”(Gal 2,19f). This mystical indwelling of God in Christ includes the mystical death of the 'I': "The decisive factor for this mystical path is the withdrawal of the 'I', more precisely the reduction of the will that constitutes the 'I'." This is not about an annihilation of the will in general, but rather the unification of the human will with the holy will of God, as exemplified in the Fiat (Let it be) of Mary at the incarnation (dwelling) of the eternal word of God: "Let it be done to me according to your word “(Lk 1.38). That is why in mysticism letting it happen and “serenity” gain outstanding importance, without the mere passivity in the sense of quietism being spoken of.

Closely connected with the indwelling of God is the cleansing of the heart, which has become hard in sin, “from all impurity and from all your idols”, through the renewing Spirit of God: “I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit in to you. I take the heart of stone from your chest and give you a heart of flesh. I put my spirit in you and cause you to follow my laws and pay attention to and fulfill my commandments. Then you will live in the land that I gave to your fathers. You will be my people and I will be your God ”(Ez 36: 25-28). This promise with the prophet Ezekiel, which is the liturgical reading in the celebration of the Easter Vigil, comes to fulfillment with the Pentecostal outpouring of the Spirit into the hearts of believers (Acts 2,3f; Rom 5,5). The will of God no longer appears as an externally imposed 'yoke of the rule of God', but as divine love of friendship with God, effective from within (cf.Jn 15: 13-17), of filing as a child of God (Rom 5: 2; 8:21; 1 Jn 3,1f) and the divine marriage (Jn 3,29; Eph 5,25-32; Rev 21,2f).

Mysticism of God's presence in his name

The sanctification of the name of God is the first and fundamental petition of the Lord's Prayer (Mt 6,9). It includes the purification of the heart (Mt 5: 8) by the Spirit of God, who appears not only in the image of water (Ez 36:25), but above all in the image of fire (Acts 2,3). The overshadowing of Mary with the Holy Spirit (Lk 1.35 analogous to Pentecost for the Church) is understood in Christian orthodoxy from the burning, but not burning, thorn bush , in which Moses receives the revelation of God's name (Ex 3.14). The connection between Ex 3.14 and the virgin birth was first established by Gregory of Nyssa among the church fathers : "Just as the thorn bush here embraces the fire and does not burn, so the virgin gives birth to the fire and is not harmed." "The Mother of God does not appear in the thorn bush, but it is the non-burning thorn bush, and in it is fire, in it is God. "Joseph Ratzinger says the same with regard to the 'High Priestly Prayer' (Jn 17) of Jesus Christ:" Christ himself appears as him burning bush, from which the name of God comes to people. (...) Christology or belief in Jesus as a whole becomes an interpretation of the name of God and what it means. "And:" What began at the burning bush in the desert of Sinai is completed at the burning bush of the cross. "

The name of God “I am who I am” refers to the pure presence of God: “The word 'howe', 'presence' in itself, then also contains the root of the concept of being. Where God gives Moses his name by the burning but not burning bush, he also says the decisive 'I am who I am', i.e. the I form of being. The tetragram [YHWH] is then the third person, the He-form, and could be translated as 'He is (always present)'. Hence, in certain Jewish circles, the tetragram is simply translated as 'he'; more often than 'the Eternal'. With the name 'Lord' time comes into the world as a constant presence. ”In the Kabbalistic number mysticism , the tetragram is read as 10-5-6-5, that is 10 = 5 'and' 5: they are in the name of God both sides of creation one.

Mysticism can therefore be understood “as a way to be present with the First Principle, God”; Jewish thought as a way to “ reach the presence of God himself through ascending knowledge of the Torah and its mysteries ”, Christian as a way, “an immediate presence with God as absolute unity or an immediate presence with Christ, for example through contemplation in the manner of the clergy Exercises' of Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556) to obtain ”.

Creation mysticism and wisdom

The preference of mysticism for fire as a symbol of divine love and the divine spirit is also shown in the focus on heaven and the 'heavenly natures' - the 'Serafim' are the 'burning'. The Hebrew word for 'heaven', shamayim , unites the earthly opposites of fire (spirit) and water (matter) in the highest possible way: “The word 'shamayim' is also used as a contraction of the words 'esch' (fire) and Seen 'majim' (water), thus again expressing the possibility of opposites in the same place at the same time. ”While the syllable 'shame' means a certain place ('there') in the sense of 'here or there', falls in the unity of heaven the opposite is gone. The 'principle of contradiction', the 'principle of contradiction to be avoided', which constitutes the occidental concept of science, is therefore no longer applicable to the religious or mystical 'heaven'. Mysticism is such a form of wisdom , that is, that (co-) knowledge “which is principally intended for the gods to whom God is intended, but also for those people who participate in this unified way of contemplative thinking that extends beyond the discursive understanding ". Wisdom appears "as a mental faculty to recognize even those experiences that appear contradictory to the mind or inaccessible to the mind and to implement them in life practice."

Man himself represents a synthesis of polar components such as soul and body, spirit and sensuality, reason and instinctual nature, infinity and finiteness, 'male' inside and 'female' outside. Maximus Confessor (around 580 - 662), the most important Greek church father of the 7th century, based on Origen built a theology of salvation of 'ascent' in 'syntheses': In humans the “great mystery of God's plan of creation should be revealed”, namely “all extremes of creation unite with one another and into the common one Unification in God ”. For Maximus, the transition from the created world of polarity to the Creator takes place in the ecstatic love union and the highest culmination of all virtue and wisdom in the power of the incarnated Logos (= wisdom), whose unity of the two natures of deity and humanity in the 'hypostatic Union '(according to the Council of Chalcedon , 451) gives the cosmos as a whole a god-human structure: “And with us and for us He [Christ] embraced the whole creation through what is in the center, the extremes as being part of Himself ... He recapitulated in Himself all things, showing that the whole creation is one ... "

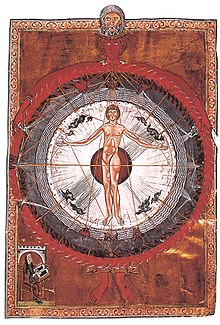

This vision, which includes the whole cosmos in the incarnation of the Creator's Word, finds its continuation in a certain sense in the mystical heaven and cosmos visions of Hildegard von Bingen . For the great Benedictine woman, love is symbolized in the “fiery life” of the triune deity, which she sees in the form of the “cosmos man”; this figure says of himself in her first vision: “Everything burns through me alone, just as the breath constantly moves people, like the wind moving flame in the fire. All of this lives in its essence and there is no death in it. Because I am life. "

In the 20th century, the French paleontologist and Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955) did not approach the creation mysticism of Maximus and Hildegard . In his vision of the unity of God and the world, Jesus Christ is the decisive “mediating figure”, namely as the “omega of creation (cf. Rev 22:13)”, that is, as the last point of convergence and goal ( causa finalis ) of the entire evolutionary process History of the universe and humanity: “God is not only incarnated in the flesh, he is incarnated in matter: Christ amictus mundo, Christ clothed with the world. (...) Evolution is therefore not a simple natural law process, blind-mechanical; it is the expression of a lasting creative power, a constant encouragement. (...) Matter becomes spirit, spirit becomes person, person becomes the absolute person of Christ - universe and Christ collapse, so to speak, towards one another and into one another. "" Not only man, let alone the soul, rather the entire earth is redeemed, dissolved, according to Teilhard, not only involved in participation, but also in the transformation into divine flesh and fire. ”For Teilhard, the“ witness of fire ”, God works creatively as fire, the universal unity:“ Esse est uniri, being is becoming one. 'Above everything is just one!' But just one out of many, not one out of the same. ”From his creation mysticism, Teilhard also sees the Sacred Heart mysticism and piety ( Margareta Maria Alacoque ) emerging in Paris in the 17th century with new eyes (see quotations) .

Mysticism of Descent and Church

The birth of God in the heart of the redeemed as a new creation (2 Cor 5:17) corresponds on the side of Revelation to the birth of the church from the opened side wound of the Savior; for in the prominent elements water and blood (Jn 19:34) the church fathers see the two sacraments baptism and the Eucharist represented, which constitute the church as a mystery of unity in faith: “In this mystery [of faith] he (Jesus) his death destroys our death and his resurrection creates life anew '. Because from the side of Christ, who fell asleep on the cross, the wonderful mystery of the whole church emerged. ”With a view to the 'nuptial' self-giving of the crucified one to the church and both nuptial 'being one flesh' in Eph 5,30f (according to Gen. 2.24) says the Basel mystic Adrienne von Speyr , this is “perhaps the greatest mystery of Christianity.” Hildegard von Bingen sees it similarly: “When Christ Jesus, the true Son of God, hung on the wood of passion, the church became his married in the secrecy of heavenly secrets, and she received his purple blood as a wedding gift. ”Birth, marriage and death coincide in the mystery of the cross from a mystical point of view.

While the chosen people of God Israel understand themselves as the “bride of God” (Isa. 61,10; 62,4f; Hohes Lied ), the idea of a (mystical) “body” of God or Christ means a certain transcendence of the Old Testament (although knows the Kabbalah quite the idea of a 'mystical figure of the deity'). The 'choosing love' of God for his people Israel and so for all of humanity and creation can be seen, as Pope Benedict XVI. In his first encyclical Deus Caritas Est explains, “can be described as Eros , which of course is at the same time entirely agape . (...) The image of the marriage between God and Israel becomes reality in a way that was previously unimaginable: Through communion with the surrender of Jesus [on the cross] communion with his body and blood becomes communion: the ' The mysticism of the sacrament, which is based on the descent of God to us, reaches further and leads higher than any mystical ascent movement of man could reach. "

In the case of the Jesuit Erich Przywara , with a view to the Ignatian exercise, practicing fellow suffering ('Compassio') to unity with Christ is almost “equivalent to the 'Unio mystica' of tradition - in the community of suffering with Christ it is a matter of 'descending Ascent '[Hugo Rahner],' Below becomes above in Christ '. ”With a view to the' alienation '(kenosis) of Christ in his incarnation (Phil 2,5-11) and already in creation, Przywara can also speak of' 'slave-like 'Descent and' wedding-like 'ascent of Christ ”.

The idea of the sacramental church constituted by baptism and the Eucharist as the mystical body of Christ , which Paul founded (Rom 12: 4f; 1 Cor 10:17; 12: 12-27) and which was further developed in the Middle Ages, leads in the encyclical Mystici corporis (1943) by Pius XII. to an identification of the Roman Catholic Church and the mystical body of Christ. However, this identity is not to be understood in such a way that criticism of the church would no longer be possible, which is always also an unholy church of sinners and on the path of pilgrimage : “The new, not man-made temple is there, but it is at the same time Still under construction. The great gesture of embracing the crucified Christ has not yet reached its goal, it has only just begun. The Christian liturgy is liturgy on the way, liturgy of pilgrimage towards the transformation of the world, which will take place when 'God is all in all' [1 Cor 15:28]. "

Mysticism and church criticism

This necessity of constant further building and inner growth of the church (cf. 1 Cor 3: 5–16) is exemplified in Francis' vocation vision . When Poverello retired to a lonely place to pray in the little church of San Damiano in 1207, he was instructed by the cross to restore the dilapidated house of God ( Domus Dei ): “He entered the church and began fervently in front of you Praying the image of the Crucified, who affectionately and kindly addressed him as follows: 'Francis, don't you see my house falling into disrepair? So go there and restore it to me! '"This vision and this building contract express - as Mariano Delgado and Gotthard Fuchs say in the introduction to their three-volume work on the Christian mystics -" the real concern of the mystics' criticism of the church. "

In contrast, a theology and church critic like Eugen Drewermann advocates a mysticism of the absolute as the (self-) abolition of creation, biblical revelation, theology and church. Drewermann wants nothing less than a “re-establishment of 'theology' beyond the domain of understanding, that is, in the realm of mysticism .” “The discovery of mysticism is that the God who appears to man as the“ Creator ”is strictly from the deity must be distinguished itself. (...) Everything that is in the Godhead is one, and one can not talk about it. God [the creator] works, the deity does not work, it has nothing to work, in it there is no work. She never looked for a work. God and deity are differentiated by working and non-working. ”“ The idea of a 'creator' also represents… a 'projection' that needs to be resolved ; But what remains afterwards is not simply nothing, on the contrary, it is the experience of an unfounded, unfounded being that we ourselves are and that at the same time lies in everything and therefore connects us with everything. That is 'something' that is mysterious, wonderful, sacred, ultimate, absolute, which is more than all 'nature'. And it is precisely for this 'more' and for this 'other' that we long for, although we are only able to find it in ourselves. ”Thus“ the previous form of 'God's speech', the 'theology' , necessarily lifts itself into mysticism up as soon as she begins to understand herself! "

Here the goal, being one with the one God, is played off against the path, becoming one as the work of God's grace in Christ's work of salvation. Christian mystics, however, have always held on to the fact that there is a Scala paradisi , a 'ladder' (see Jacob's ladder ) or a stepped path of ascent in descent, and that therefore spiritual exercises have their meaning and place like the Lectio divina : a God Dedicated 'reading' of the Holy Scriptures with the stages lectio ('reading'), meditatio ('meditation'), oratio ('prayer'), operatio ('doing') and contemplatio ('contemplation'). “The aim of the Lectio divina is contemplation, union with God. (...) The attainment of contemplation is a divine gift of grace and not something that the person who is praying can consciously bring about, but only allow it to happen to himself. Prayer is then no longer something the person who is praying does, but something he is, a permanent state. Mysticism calls this state 'prayer of the heart'. In this state the prayer is as it were as a whole living prayer. "

Hubertus Mynarek goes in a different direction in his work: Mystik und Vernunft , 2nd ed., Münster 2001. In this work he describes mysticism in general and its relationship to reason. He comes to the conclusion that mysticism and reason diverge, but that man can only transcend reality through a synthesis of mysticism and reason.

Mysticism and emancipation

In the Catholic Church, the binding interpretation of Scripture belongs exclusively to the clergy. Mystics, on the other hand, often consider themselves “called to be divinely authorized exegetes of Scripture” through their visions. Hildegard von Bingen z. B. describes a vision in the preface to her work Scivias and continues: "And immediately I understood the importance of the holy books - the Psalter, the Gospels and the Catholic Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments." This renunciation of the mediating position of the clergy between God and man can also be recognized from book illustrations. When the “appeal to a divine command” led to disobedience, Hildegard appealed to the church authorities on the “incontestable authority of her vision”. As a result of this relativization of the precedence of the clergy in the mediation of salvation, which is widespread among mystics, many came under suspicion of heresy and became a case for the Inquisition.

Quotes

“The plants and the animals give each other the fire that they breathe. Because the breath is fire. The animals inhale oxygen and exhale carbon. When the oxygen enters the animal's lungs, it renews its life and purifies its blood because it heats it up. The exchange takes place day and night between the trees and us. The earth has underground volcanoes, the sea has volcanoes under water. Everything that has life is on fire. Creation is a work of love, and all its members ceaselessly give one another the alms of fire. The fire purifies, the fire illuminates, the fire unites. It restores after decomposing. In this way, it symbolizes the three forms of mystical life in a mysterious way: the purifying, the illuminating and the perfecting and perfecting life in God. "

“[In the] rite of consecration of baptismal water, reflections from the history of religion can be seen of a symbolic performance of the nocturnal 'Hieros Gamos' between God and creation, which is performed on Easter vigil between the risen Christ and the Church, in order to allow the birth of new children of God in the subsequent baptism enable. The expression of this cultic marriage and the symbolic fertilization of the water is the three times lowering of the Easter candle into the baptismal water fountain ... Christianity already has a connection between night and bride mysticism, as will be found expressly in John of the Cross and later in Novalis not alien to early forms of expression. "

“Now, in a sudden reversal, it becomes apparent that you, Jesus, through the 'revelation' of your heart wanted above all to give our love the means to escape from what was too narrow, too sharply defined, too limited in the picture that we made of you. In the center of your chest I don't notice anything other than an embers; and the more I look at this burning fire, the more it seems to me that the outlines of your body are melting all around it, that they become larger beyond all measure, until I recognize no other features in you than the figure of one that is on fire World. ”“ As long as I was only able and daring to see in you, Jesus, the man from two thousand years ago, the exalted moral teacher, the friend, the brother, my love has remained timid and restrained. (...) So for a long time I myself wandered around as a believer without knowing what I loved. But today, master, when you appear to me through all the powers of the earth through the revelation of the suprahuman [superhuman] faculties which the resurrection has given you, I recognize you as my ruler and surrender myself to you with delight. "

“In a famous passage he describes [John of the Cross] Christ as the last word of the Father, in which, according to Col 2, 3 'all the treasures of God's wisdom and knowledge are hidden,' which is why it is presumptuous, yet another word of revelation from God expected (2 S [ubida del Monte Carmelo], 22.7.6); rather, one should strive to discover the treasures deeply hidden in Christ. The whole church as a whole must learn to look to the crucified Christ and to listen to Christ as the last word of the Father, for there is still much to discover in him: 'So there is much that needs to be deepened in Christ because he is like an overflowing mine with many corridors full of treasures; no matter how much one delves into them, one never finds an end and end point for them, on the contrary, in every passage one comes here and there to find new veins with new riches. ' The treasures of God's wisdom and knowledge are so hidden in Christ, 'that most of the holy scholars and holy people have yet to say and understand how many mysteries and miracles they have uncovered or understood in this life'. "

See also

- Mystical experience

- List of mystics

- Christ and the mincing soul , (14th century), monastic teaching poetry

- Christ and the seven shops

literature

- Research literature

- Sabine Bobert : Jesus prayer and new mysticism. Foundations of a Christian mystagogy. Kiel 2010, ISBN 978-3-940900-22-7 (online: Cover , pp. 1–29 ).

- Bardo Weiss: Jesus Christ among the early German mystics . Part II: The Work, Paderborn 2010

- Mariano Delgado, Gotthard Fuchs (ed.): The church criticism of the mystics. Prophecy from Experience of God , 3 volumes, Freiburg-CH / Stuttgart 2004–2005

- Klaus W. Halbig: The tree of life. Cross and Torah in mystical interpretation , Würzburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-429-03395-8

- Marco S. Torini: Apophatic Theology and Divine Nothing. About traditions of negative terminology in occidental and Buddhist mysticism . In: Tradition and Translation. On the problem of the intercultural translatability of religious phenomena . De Gruyter, Berlin a. a. 1994, pp. 493-520.

- Peter Zimmerling: Evangelical mysticism . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-525-57041-8

- Read books

- Gerhard Ruhbach, Josef Sudbrack (ed.): Christian mysticism. Texts from two millennia. C. H. Beck, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-406-33622-1

- Introductions

- Peter Dinzelbacher : German and Dutch mysticism of the Middle Ages: A study book . De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-022137-4 .

- Peter Dinzelbacher: Christian Mysticism in the Occident. Your story from the beginning to the end of the Middle Ages . Schöningh, Paderborn 1994.

- Otto Langer: Christian mysticism in the Middle Ages. Mysticism and Rationalization - Stations of a Conflict. WBG, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-04527-0 .

- Bernard McGinn : The Mysticism of the Occident. (German translation from: The Presence of God, A History of Western Christian Mysticism. ) 4 of 5 planned volumes already published, Herder, Freiburg 1994 ff., ISBN 978-3-451-31062-1 .

- Kurt Ruh : history of occidental mysticism. 5 volumes. C. H. Beck, Munich 1990-1999.

- Uta Störmer-Caysa : Introduction to medieval mysticism. New edition Reclam, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-15-017646-8 .

- Hildegard Gosebrink : Seeing the secret. Basic course in Christian mysticism. Kösel, Munich 2007, ISBN 3-466-36744-1 .

- Werner Thiede : Mysticism in Christianity . Frankfurt a. M. 2009, ISBN 978-3-86921-003-2 .

- Hubertus Mynarek : Mysticism and Reason . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Münster 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5312-8 .

- Gerhard Wehr : Christian mystics. From Paulus and Johannes to Simone Weil and Dag Hammarskjöld . Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2147-7 .

- reference books

- Peter Dinzelbacher (Ed.): Dictionary of Mysticism (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 456). 2nd, supplemented edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-520-45602-8 .

Web links

- Joseph Schumacher : The mysticism in Christianity and in the religions (PDF file; 1.1 MB), Freiburg i. Br., Lecture in the winter semester 2003/2004

- Society of Friends of Christian Mysticism ; Ecumenical association for the promotion of mystical traditions in Christianity for the German-speaking area

Individual evidence

- ↑ A compact overview of the various attempts at definition is provided e.g. B. Bernard McGinn : Presence of God: a History of Western Christian Mysticism . 5 volumes, also in German translation by Herder, 1994 ff., Here vol. 1, 265 ff. Almost every introduction to the topic gives an answer to problems of definition, for example: Volker Leppin : Die christliche Mystik , C. H. Beck, 2007.

- ↑ Bernard McGinn: The Mysticism of the Occident. Herder, 2005, Vol. 4, pp. 291, 505.

- ^ F. Wulf: Mystik . In: Handbuch theologischer Grundbegriffe , Volume 3, Munich 1970, pp. 189–200; Werner Thiede : mysticism in the center - mysticism on the edge . In: Evangelisches Sonntagsblatt aus Bayern 13, 2006, p. 7 ( Memento from April 7, 2016 ( Memento from April 7, 2016 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ John Sanford: The Gospel of John. A depth psychological interpretation , 2 vol., Munich 1997, vol. I, p. 47.

- ↑ See Saskia Wendel: Christian Mystik. An introduction , Kevelaer 2004, pp. 27–85.

- ^ Walter Kasper: Prolegomena for the renewal of the spiritual interpretation of scriptures. In: ders., Theologie und Kirche , Vol. 2, Mainz 1999, 84–100, here p. 99f.

- ↑ See Klaus W. Halbig: The Tree of Life. Cross and Torah in a mystical interpretation , Würzburg 2011, pp. 87–93 (The mystical understanding of scripture as a love affair with the Torah).

- ↑ Gershom Scholem: Zur Kabbala und their Symbolik , Frankfurt 1973, 49–116 (The meaning of the Torah in Jewish mysticism), here p. 70 and p. 87 (see p. 98f).

- ↑ In Lev. Hom. 5.3 - cit. after Photina Rech: Inbild des Kosmos. A symbolism of creation , 2 vols., Salzburg 1966, vol. II, 50–93 (fire), here p. 84; see. ibid. p. 64f.

- ↑ Cf. Corinna Mühlstedt: Die christlichen Ursymbole , Freiburg u. a. 1999, pp. 59-61.

- ↑ See the article “Mystik” in the Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche³ , Vol. 7, Col. 583 to Col. 597, here Col. 587.

- ^ P. Rorem: The ascent spirituality of Pseudo-Dionysius. In: Bernard McGinn et al. (Ed.): History of Christian Spirituality , Vol. I: From the beginnings to the 12th century, Würzburg 1993, 154–173, here p. 161. In addition Beate Regina Suchla: Dionysius Areopagita. Life - Work - Effect, Freiburg 2008.

- ↑ Otto Langer: Christian mysticism in the Middle Ages. Mysticism and Rationalization - Stations of a Conflict. WBG, Darmstadt 2004, p. 151ff. ISBN 3-534-04527-0 .

- ↑ Quoting from Otto Langer: Christian Mysticism in the Middle Ages. Mysticism and Rationalization - Stations of a Conflict. WBG, Darmstadt 2004, p. 189. ISBN 3-534-04527-0 .

- ↑ Hans Urs von Balthasar: Glory. A theological aesthetic , vol. II: subjects of styles, part 1: clerical styles, Einsiedeln ² 1969, p. 211.

- ↑ Saskia Wendel: Christian mysticism. An introduction , Kevelaer 2004, p. 118.

- ↑ For the so-called cognitio dei experimentalis see z. B .: Ulrich Köpf, Art. Experience III / 1, in: Horst Robert Balz et al .: Theologische Realenzyklopädie. , Vol. 10, De Gruyter, 1977, p. 113.

- ↑ Mariano Delgado, “There you alone, my life!” The God-drunkenness of John of the Cross. In: ders./ AP Kustermann (ed.): God's crisis and God drunkenness. What the mysticism of contemporary world religions has to say , Würzburg 2000, 93–11, here p. 95f and p. 97.

- ↑ Joseph Sudbrack, “Finding God in All Things”. An Ignatian maxim and its metahistorical background. In: Geist und Leben 3/1992, 165–186, here p. 182 (with reference to Erika Lorenz).

- ↑ Peter Zimmerling: Evangelical Spirituality, Roots and Approaches, Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht 2003, p. 22 ff.

- ↑ Michel Cornuz: Le protestantisme et la mystique , Genève 2003

- ↑ Winfried Böhm : Theory of Education. In: Winfried Böhm, Martin Lindauer (ed.): “Not much knowledge saturates the soul”. Knowledge, recognition, education, training today. (= 3rd symposium of the University of Würzburg. ) Ernst Klett, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-12-984580-1 , pp. 25-48, here: pp. 32 f.

- ↑ Peter Koslowski: Philosophies of Revelation. Ancient Gnosticism, Franz von Baader, Schelling , Paderborn et al. 2001, p. 761f. (Baader criticizes Hegel's philosophy of the 'abolition' of the finite in the infinite as an 'adventurous mysticism of infinity': “God understands this mysticism of infinity as the infinite, as the poor god Saturnus who eats his children in order to keep himself alive.” P. 792; cf. 763-765 as well as 775-786 and esp. 791-794).

- ↑ Hubert Wolf: The nuns of Sant'Ambrogio. A true story , CH Beck, Munich 2013, pp. 159–164 ("Mystik und Mystizimus")

- ^ Karl Rahner: Piety Today and Tomorrow. In: Geist und Leben 39 (1966), 326–342, here p. 335; likewise in the draft lecture piety then and now. In: ders., Schriften zur Theologie , Vol. 7, Einsiedeln 1966, 11–31.

- ↑ Pope Benedict XVI. “Verbum Domini. On the Word of God in the life and mission of the Church ”, Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation of November 2010, n. 2.

- ↑ Heilig Kreuz - Center for Christian Meditation and Spirituality - program September 2016 to July 2017. (PDF) Heilig Kreuz - Center for Christian Meditation and Spirituality, June 14, 2016, accessed on November 29, 2016 .

- ↑ Siegfried Ringler (Ed.): Departure for a new God's speech. The mysticism of Gertrud von Helfta , Ostfildern 2008, p. 13 (S. Ringler).

- ↑ See Klaus W. Halbig: The Tree of Life. Cross and Torah in a mystical interpretation , Würzburg 2011.

- ^ Bernhard Uhde: West-Eastern Spirituality. The inner ways of the world religions. An orientation in 24 basic terms (with the help of Miriam Münch), Freiburg 2011, 66–76 (mysticism), here p. 68.

- ↑ Quoted from Karl Suso Frank: “Born from the Virgin Mary”. The testimony of the ancient church. In: ders. U. a., On the subject of virgin birth , Stuttgart 1970, p. 104.

- ^ Karl Christian Felmy, quoted in after Michael Schneider: Hymnos Akathistos . Text and explanation (Ed. Cardo, Vol. 119), Cologne 2004, p. 61, note 69. Felicitas Froboese-Thiele describes a spiritual experience analogous to this in a certain way: Dreams - a source of religious experience? With a preface by CG Jung, Darmstadt 1972, pp. 76-78 (“Das Feuer im Spankorb”).

- ^ Joseph Ratzinger: Introduction to Christianity. Lectures on the Apostles' Creed , Munich 1968, pp. 98f.

- ↑ Joseph Ratzinger (Benedict XVI.): Jesus of Nazareth. First part: From Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration , Freiburg 2007, p. 178 (on the relationship between thorn bush and Eucharist see p. 179).

- ↑ Friedrich Weinreb: Inner world of the word in the New Testament. An interpretation from the sources of Judaism , Weiler 1988, p. 29.

- ^ Friedrich Weinreb: number sign word. The symbolic universe of Bible language , hamlet i. General 1986, pp. 92-97.

- ^ Bernhard Uhde: West-Eastern Spirituality. The inner ways of the world religions. An orientation in 24 basic terms (with the help of Miriam Münch), Freiburg 2011, 66–76 (mysticism), here p. 71.

- ^ Friedrich Weinreb: Creation in the Word. The structure of the Bible in Jewish tradition , Zurich ²2002, p. 238.

- ^ Bernhard Uhde: West-Eastern Spirituality. The inner ways of the world religions. An orientation in 24 basic terms (with the help of Miriam Münch), Freiburg 2011, 140–150 (Science - Wisdom), here p. 147.

- ↑ Quoted from Felix Heinzer: God's Son as Man. The structure of the human being of Christ in Maximus Confessor , Freiburg (Ch) 1980, 157–160 (The central position of man in the cosmos), here p. 159.

- ^ Lars Thunberg: Man and the cosmos. The vision of Saint Maximus the Confessor , New York 1985, 80-91 (The fivefold mediation of man as perfect realization of the theandric dimension of the universe), here p. 90 (with reference to Col 1.20).

- ↑ Hildegard von Bingen: See God , trans. and a. by Heinrich Schipperges (texts Christian mystics, 522), Munich a. a. 1987, p. 37.

- ↑ Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz: "Son of the Earth": Teilhard de Chardin. In: International Catholic Journal Communio 34 (2005), 474-480, here p. 475f.

- ↑ Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz: "Son of the Earth": Teilhard de Chardin. In: Internationale Katholische Zeitschrift Communio 34 (2005), 474–480, here p. 476.

- ↑ Second Vatican Council: Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy , n.5.

- ^ Adrienne von Speyr: Children of the light. Reflections on the letter to the Ephesians , Einsiedeln 1950, pp. 207f.

- ↑ See Klaus W. Hälbig: The wedding on the cross. An introduction to the middle , Munich 2007 (on Hildegard cf. Scivias II, 6, here p. 721).

- ↑ Benedict XVI., God is love - The encyclical "Deus caritas est" . Full edition, come on. by W. Huber, A. Labardakis and K. Lehmann, Freiburg u. a. 2005, n.9 and n.13.

- ^ Stephan Lüttich: Night experience. Theological dimension of a metaphor (studies on systematic and spiritual theology 42), Würzburg 2004, 185–190 (figure of night with Ignatius von Loyola), here p. 188, and 242–299 (night as Locus theologicus: theology of night and night der Theologie with Erich Przywara), here p. 253.

- ↑ Joseph Ratzinger: The Spirit of the Liturgy. An introduction , Freiburg u. a. 2000, p. 43.

- ↑ Legend of three companions of St. Francis 13; see. Leonhard Lehmann: “Go there, restore my house!” Considerations on the Franciscan basic mandate. In: Geist und Leben 2/1991, 129–141, here p. 130.

- ↑ Mariano Delgado / Gotthard Fuchs (ed.): The Church Criticism of the Mystics. Prophecy from experience of God , 3 vols., Freiburg-CH / Stuttgart 2004/2005, vol. 1, p. 18.

- ↑ Eugen Drewermann: The sixth day. The origin of man and the question of God (Faith in Freedom, Vol. 3 - Religion and Science, Part 1), Zurich a. a. ²1998, SS 432 and pp. 329f.

- ↑ Eugen Drewermann: The sixth day. The origin of man and the question of God (Faith in Freedom, Vol. 3 - Religion and Science, Part 1), Zurich a. a. 1998, p. 334.

- ^ Daniel Tibi: Lectio divina. Meet God in his word. In: Geist und Leben 3/2010, 222-234, here p. 233f.

- ↑ In the Catholic Church it is still valid today that "the binding interpretation of the good of faith [...] is the sole responsibility of the living magisterium of the Church, that is, the successor of Peter, the Bishop of Rome, and the bishops in communion with him". Catechism of the Catholic Church. Compendium , Pattloch, 2005, p. 29

- ↑ Otto Langer: Christian mysticism in the Middle Ages . Mysticism and Rationalization - Stations of a Conflict. WBG, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-04527-0 , p. 180.

- ↑ Quoted in: Donald F. Logan: Geschichte der Kirche im Mittelalter , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005, p. 189

- ↑ Donald F. Logan: History of the Church in the Middle Ages , Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2005, p. 193

- ↑ Otto Langer: Christian mysticism in the Middle Ages . Mysticism and Rationalization - Stations of a Conflict. WBG, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-04527-0 , p. 221

- ↑ Hubert Wolf: The nuns of Sant'Ambrogio. A true story , CH Beck, Munich 2013, p. 130

- ↑ Ernest Hello: Mensch und Mysterium , Heidelberg 1950, 132-140 (Das Feuer), here p. 132f.

- ^ Stephan Lüttich: Night experience. Theological dimension of a metaphor (= studies on systematic and spiritual theology 42), Würzburg 2004, p. 36.

- ↑ Teilhard de Chardin: Lobgesang des Alls , Olten 1964, 9–42 ( The Mass about the World ), p. 36f.

- ↑ Mariano Delgado: “There you alone, my life!” The God-drunkenness of John of the Cross. In: ders., Abraham P. Kustermann (Hrsg.): God's crisis and God drunkenness. What the mysticism of the contemporary world religions has to say , Würzburg 2000, 93–117, here p. 112 and p. 93.