Millstatt Abbey

The pin Millstatt is a former monastery in Millstatt am See in Austria . The collegiate church and Millstatt cloister are among the representative Romanesque buildings in Carinthia , particularly because of their abundant animal symbolism . The monastery was founded before 1122, probably around 1070, and was administered by the Benedictines (OSB). In 1469 the Order of St. George Knights took over the monastery; after its decay in 1598 it was given to the Jesuits (SJ). It was finally abolished in 1773 under Joseph II. Today the church belongs to the parish, all other buildings of the former monastery are under state administration ( Austrian Federal Forests ). For centuries, the monastery was the spiritual and cultural center of Upper Carinthia . With its possessions around Lake Millstatt , in the Görtschitztal , in Friuli and in Salzburg, it was one of the most important in Carinthia.

history

founding

The Millstatt Abbey was founded by the Aribo II brothers , a former Count Palatine, and Poto (also Boto) from the Bavarian family of the Aribones . A deed of foundation has not been received, the year of foundation can only be identified indirectly. A traditional note mentions a legal transaction between Aribo and Archbishop Gebhard von Salzburg , including the tithe for Aribos regarding two churches in Millstatt (due ad Milstat site) . Gebhard, who held office from 1060 to 1088, had made extensive toe adjustments around 1070. Since he was outlawed as an opponent of King Henry IV between 1077 and 1086 and stayed in Swabia during this time, while Aribo was a follower of Heinrich, only the years 1060 to 1077 and 1086 to 1088 remain for the foundation, whereby the research is closed the earlier time window tends to.

Aribo and Poto are also referred to as founders in Millstatt's book of the dead from the 13th century: Aerbo com. palatinus et fundator huius ecclesie and Poto com. et fundator huius ecclesiae . The Duke Domitian (Domitianus dux fundator huius ecclesiae) , mentioned as founder in the same Book of the Dead as early as the 12th century, is referred to the realm of legends by some historians. However, it cannot be ruled out that, long before the monastery founded by Aribo and Poto, a monastery existed in Millstatt at the time of the Carolingians .

The Benedictine monastery (around 1070 to 1469)

The first documented abbot is Otto I, who had a lasting effect from 1122/24 to 1166 and was prior of Admont Abbey . For a long time Gaudentius from the Hirsau Monastery in the Black Forest was considered to be the first abbot to be elected Abbot of Millstatt between 1091 and 1105.

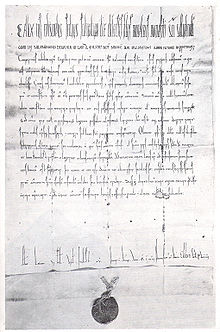

In 1122, the Count Palatine Engilbert, a brother of the first Count of Gorizia , Meinhard I, placed the monastery under the protection of the Pope. Before that it was a monastery owned by the donor family. The document issued by Pope Calixt II , in which he takes Millstatt “sub beati Petri patrocinio” (under the protection of the Holy See), is also the oldest surviving document pertaining to the monastery. At the same time it was named as a Benedictine monastery , but was probably already founded as such.

The counts of Gorizia remained hereditary bailiffs until they died out in 1389, although they were "not very concerned about the welfare of the churches entrusted to them" . The tensions with the Görzer Vogtherren could also have been the reason for the writing of a Domitian legend, with which the monastery wanted to pretend to be the foundation of the former sovereign. The monastery received numerous papal privileges in the 12th century, but was not exempted , which was also reflected in the visitation right of the Archbishop of Salzburg.

The abbots Otto and Heinrich II. (1166 to after 1177), who were appointed from the reformed monastery of Admont, brought Millstatt to both economic and cultural importance, which would last into the 15th century. During this time there was an important scriptorium in the monastery, in which numerous manuscripts were created, including the Millstätter manuscript .

In 1177 Pope Alexander III. granted the Millstatt monastery a privilege in which the content of the document from 1122 was confirmed. This document also mentions the property of the monastery, which should largely coincide with the foundation property: extensive properties in Carinthia and Friuli (San Foca) are likely to come from the property of Aribo, the properties in Salzburg ( Pinzgau ) from Poto.

The monastery reached a high point in the middle of the 13th century under Abbot Otto III. In 1245 the abbot received the pontificals (infel, ring, dalmatica and sandals) from Archbishop Eberhard von Salzburg as well as the right to perform all pontifical business with the exception of those that required holy anointing . At that time the convention had around 150 members.

Under Abbot Rudolf from 1247 the first known grievances arose, which in 1287 led to a visit to the monastery on behalf of the Archbishop of Salzburg. In the Reformation deed, it was forbidden to sell monastery property without permission, and it was ordered to remedy the abuses indicated. The former abbot Rudolf was transferred to a distant church of the monastery, "so that he could not give his fellow brothers cause and opportunity to sin by forbidden nightly meetings" . One monk was charged with murder and two others were transferred. To improve the life of the monastery, two preachers were transferred from another monastery to Millstatt. Between 1274 and 1291 the monastery was destroyed by fire and rebuilt around 1291 under Abbot Otto IV. An infirmary was mentioned for the first time in 1300; it initially received numerous donations, but was no longer mentioned after the early 14th century.

The many indulgences that the monastery received, as well as the numerous donations and donations in its favor, were also a sign of the continued prosperity of the monastery . Around the middle of the 14th century, however, the debts increased, in 1330 six monks were allowed to move to other monasteries because of the debts of the monastery, and complaints about the low status of the convent have been preserved from 1346. However, no complaints are known about religious life from the 14th century.

The monastery recovered under Abbot Johann (1367–1418), but succumbed to a noticeable decline in the 15th century under Abbots Christoph I (1418–1445) and Christoph II (1445–1469). After the Görzern, the counts of Ortenburg were bailiffs, and from 1420 the counts of Cilli . Hermann II von Cilli was considered "the great patron of Millstatt" , among other things he gave the monastery two - not named - lakes and their brooks for fishing. In 1429, during a visitation, there were again complaints about the monetary management of the monastery, in addition, in the Reformation deed, the wearing of the order's robe had to be ordered and drinking and the presence of women had to be forbidden. In 1451, Pope Nicholas V even threatened to ban them to persuade the monastery to pay debts. During a visitation in the same year as a result of the Cusan order reform , only eleven professed people were counted in the monastery . The ceremonies were properly celebrated, but the buildings were derelict and Abbot Christopher II was found incapable. In 1455 even the Vogt, Count Ulrich II of Cilli , requested a visit to the monastery.

After the last Count of Cilli, Ulrich II. Von Cilli, was murdered in 1456, Emperor Friedrich III. the bailiwick in his possession. Friedrich even interfered personally in filling individual parishes. In 1457 he issued a certificate in Millstatt, he knew the monastery and probably also the inability of Abbot Christoph II personally. At that time the monastery was only inhabited by less than ten monks and was marked by mismanagement, which manifested itself in high debts and structural deterioration. At Friedrich's instigation, the Benedictine monastery was dissolved on May 14, 1469 by the papal commissioner, Bishop Michael von Pedena , and at the same time the first Grand Master of the Order of St. George was appointed to his office.

During the four centuries of Benedictine rule in Millstatt, the monastery had 33 abbots that can be documented. They were also the secular masters between Lieseregg and Turrach .

Economic basis

The foundations of the monastery, which, as mentioned, were located in Carinthia, Friuli and Salzburg, are not exactly known, but certainly provided the monastery with a good economic base. A total of 113 purchases of goods by the monastery from the 12th to the 15th century are documented, sales are only documented from the 15th century. The goods that were alienated from the monastery are not explicitly mentioned in any documents, but they are likely to have led to a substantial loss.

One goal of the monastery was always to exchange distant goods for goods in the vicinity of the monastery, so goods from the monastery in Salzburg were repeatedly exchanged for those from the archdiocese in Carinthia. In 1446 the monastery sold all Friulian goods to Count Biachinus von Porcilli. Most of the proceeds were used to buy the Carinthian estates of the San Gallo monastery in Moggio Udinese (foundation of the Aribonen Kazelin ).

A land register was only obtained from 1470, one year after the Benedictine monastery was dissolved, but the Knights of St. George are unlikely to have made any major acquisitions that year. The Urbar only lists the property in the two offices of Millstatt and Puch, which means that the free float is not taken into account. The Urbar names: 248 Huben , 81 fiefs , 75 Schwaigen , 12 fields, 7 meadows, 15 anger , 6 gardens, 11 tithe, 3 estates, 2 courtyards, 6 Meierhöfe, 3 Neubrüche, 12½ wastes, 2 taverns, 1 mill, 1 Saw, 1 hunt, 2 Fischlehen and 1 Gereut. The monastery was therefore of considerable economic importance for Upper Carinthia.

The high level of jurisdiction was always with the bailiffs. In the 12th to 14th centuries, the monastery in Millstatt, Kleinkirchheim and San Foca was at least partially entitled to lower jurisdiction, but this was severely affected by the Gorizia. Under Count Ulrich von Cilli the monastery got the lower jurisdiction in the Millstatt district court in part and under Friedrich III. even entirely in his hand.

For a large agricultural enterprise like a monastery, strategic participation in the extraction of raw materials such as salt was very important. The levies from the dairy industry came in the form of cheese, which had to be preserved. In 1502 alone the Schwaigen supplied 17,400 cheese loaves. From the privilege of 1177 it emerges that, through Count Poto, Millstatt owned a complete operating unit for salt production in the Bad Reichenhall salt works .

Millstatt women's monastery

A women's monastery in Millstatt is documented from 1188/1190. It was subordinate to the men's monastery and was therefore certainly a Benedictine monastery, even if this is never explicitly mentioned in the few documents. In contrast to the male monastery, there were never any complaints about the nunnery in the many Reformation documents. From the names of the nuns it can be deduced that they were predominantly of ministerial and civil origin. A list of benefices for the nunnery dates from 1450; when the men's monastery was abolished in 1469, the nunnery was no longer mentioned.

The Order of St. George Knights (1469–1598)

Main article: Knights of St. George

Foundation and mission of the order

The founding of the Order of St. George goes back to a vow that Friedrich III. during the siege of the Vienna Hofburg by rebellious citizens in 1462. In the event that this danger was averted, he vowed to found a spiritual knightly order of St. George based on the model of the German Johanniter and Templer , which should primarily be commissioned to fight the Turks.

After the liberation by the Bohemian King Georg Podiebrad, Friedrich honored his vows six years later: On November 16, 1468, the Emperor and his entourage set out for Rome to present their concerns to Pope Paul II , whose confirmation he supported the Founding of the order needed. The Pope agreed and on January 1, 1469 issued the bull for the Order of St. George. At the emperor's suggestion, the Pope endowed the order with properties, including those of the dissolved Benedictine monastery in Millstatt, including the St. Martin Hospital in Vienna.

Johann Siebenhirter , a confidante of Frederick's old Viennese family, was appointed as the first Grand Master of the order , and he was appointed papal legate on May 14, 1469 by Bishop Michael von Pedena . The most important task of the order was to ensure an effective defense against the Turkish threat, the emperor expected the provision of a force of 3,000 to 4,000 men.

Despite the extensive possessions, the order was in financial difficulties from the beginning: The Benedictines had left debts and severely neglected buildings, so that the means of the St. George Knights were initially just enough for the running costs, but initially it was not possible to set up a fighting force think. In 1471, the George Knights only had eleven members. In view of the approaching Turks, however, the most urgent measure was initially to repair the building and expand the complex into a fortress.

Peasant uprising of 1478

From a military point of view, a knightly order as protection against attacks was no longer appropriate. In addition, the number of St. George's Knights remained low , despite efforts by Friedrich's successor Maximilian I to add further members to him, so that the order was never able to take military action against the Ottomans , who plundered Carinthia five times between 1473 and 1483 was. It was not only the Millstatt farmers who felt that their rule was at the mercy of the “runners and distillers” and saw this as a breach of the loyalty relationship between landlords and subjects - interest and robot against military protection. Finally, the displeasure in the neighboring county of Ortenburg erupted in the Carinthian peasant uprising of 1478 under the leadership of Peter Wunderlich. The uprising was put down, Wunderlich caught near Gmünd and executed at Litzelhof near Lendorf . Only a few years later there was again heavy looting by Hungarian troops in the Millstatt area. In 1487, Sommeregg Castle, about five kilometers away, was conquered and destroyed. Hungarian mercenaries had been brought into the country in the course of a dispute over the occupation of the diocese of Salzburg and had their headquarters in Gmünd. They got their pay by looting the area as far as Radenthein and Kaning.

Decline

Maximilian, who himself belonged to the Order of St. George from 1511, was the last sponsor of the order. Under his second Grand Master Johann Geumann (1508–1533), the building and art work of the monastery in Millstatt and the associated churches such as Matzelsdorf reached another high point, but after Maximilian's death in 1519, his successor Charles V showed little interest in the order. In a petition in 1521 Geumann complained that the monastery was “ain öd pawfellig closter. Have a look at all khain and with the paw dhain (no) want to take end. ” And there are around 180 people busy with construction work, kitchen work, school and church services. About his subordinates in the monastery he wrote around 1528: “... the members are perjury boys who love wine and chase after frivolous women who want to be completely free, they steal the estate from the rich, they let the poor die without sacrament, it would be the best thing to do is to imprison everyone for life. ” After Geumann died, the monastery and its possessions were even more neglected, and the order gradually dissolved as the possessions dwindled. A nominal abolition of the order was apparently omitted - there is no document about it - because, in the absence of a revocable convention, there was no sense in such a measure, which was bureaucratically very costly. Not a single visit to Millstatt has been recorded from the last Grand Master, Wolfgang Prandtner. If the tax burden was already felt to be appropriate in the Benedictine times - "It's a good life under the crook." - the secular and religious freedoms of Millstatt's subjects reached a climax. The administrators of the Order of St. George were unable to counter the emerging Protestantism . In the entire parish only one citizen and twelve farmers received the sacraments at that time.

The Jesuits (1598–1773)

Main article: Millstatt Jesuit rule

On July 26, 1598, the Millstatt Monastery, which was probably vacant and was abandoned by the Knights of St. George, was transferred by Archduke Ferdinand II to the Jesuits (SJ), an order founded in 1534 and confirmed by the Pope in 1540. Ferdinand, himself a strict Catholic upbringing at the Jesuit school in Ingolstadt , was convinced, in view of the Jesuits' zeal for faith, that with the help of the Jesuits he would push back Protestantism , which had fallen on particularly fertile ground in his countries in the course of the 16th century Counter Reformation could carry out. A Jesuit college had already been established in Graz in 1573 and the University of Graz , founded in 1585, had also been taken over by the Jesuits. The income from the Millstatt rulership was supposed to serve to maintain and expand it. The Father Rector of the university was the supreme landlord of the Millstatt residence.

The Jesuits soon developed a lively activity in Millstatt, they carried out the Counter-Reformation with ruthless consistency. They saw the Millstatt area as a "quasi-diocese", a "territorium separatum et nullius dioecesis" not only from the diocese of Salzburg, but also independent of tax law. In the course of 1600 all citizens and peasants had to appear before a commission which instructed them about the Catholic faith and gave them the choice of either renouncing Protestant teaching and returning to the Catholic Church or leaving behind a tenth of their belongings within three To emigrate months. In contrast to earlier times, the Jesuits insisted on the exact fulfillment of the tax obligations, which the subjects were not used to. The protests culminated in the peasant uprising (Millstätter Handel) of 1737.

The Jesuits could not survive in the area of tension between the Catholic nobility, who demanded vehement action against the Protestants in order to maintain power, and the self-interest of the Jesuits as landlords to have economically strong subjects. From 1753 onwards, by founding missionary districts, Empress Maria Theresia ignored the protesting Jesuits who insisted on their autonomy and had mission stations set up with clergymen who were independent from Millstatt. The so-called Jesuit ban , which by a papal bull on 21 July 1773 by Clement XIV. Was pronounced, and the Millstätter Jesuit order was dissolved. This sealed the end of Millstatt Monastery as a monastery.

From today's perspective, the deportation of evangelicals to Transylvania, for example, was completely ineffective. After Emperor Joseph II issued the patent of tolerance in 1781, tolerance communities were formed in Upper Carinthia exactly where Protestant religious life had gone underground after 1600.

After the repeal until today

The Jesuits cleared the monastery and took all relevant movable art treasures with them to their main branches in Graz and Klagenfurt, leaving the old monastery plundered. The Carinthian rule of repealed Monastery of the Lieser to Turrach, which, on being dissolved 21 control communities with an extent of 65,146 Lower Austrian yoke included and 7,426 inhabitants, the state study fund company was assumed and a Kameralpfleger was entrusted with the administration. At the time of its dissolution in Carinthia, the Jesuit order had 28 members; In the Millstatt Monastery there were still eleven priests and four brothers under Superior Ignatz Tschernigoy.

The fifteen Jesuits had to leave Millstatt, while Tschernigoy was allowed to remain in his place of work as pastor of the former collegiate church, which was declared the parish church of Millstatt and, like other Millstatt parishes , was assigned to the diocese of Gurk in 1775 . The well-known fruit growing of the monks was not continued, which Weinleitn herbed. Some branch churches such as Obermillstatt became independent parishes. The remaining monastery buildings were used for other purposes and the movable inventory was partly scattered; Works in the monastery library can now be found all over Europe, most of the documents in the Vienna House, Court and State Archives , and other files in the Carinthian State Archives . The coffered ceiling of the knight's hall is now in Porcia Castle in Spittal an der Drau. The monastery buildings fell into disrepair in the following years. It was not until the history association for Carinthia founded by Gottlieb von Ankershofen in 1844 that scientific interest in Millstatt was awakened and work on monument conservation began.

The church is still used today as a Catholic parish church. It reports to the Gmünd-Millstatt deanery of the Gurk diocese. The Order of St. George , which returned from Rome in 1993 and flourished again, has its nominal and spiritual seat in Millstatt again.

The only branch church of the Millstatt parish is the chapel on Kalvarienberg above the monastery. From 1901 a hotel ("Lindenhof") was housed in the south wing of the Order's Palace, the former Grand Master's Palace, and the inner courtyard around the 1000-year-old linden tree serves as a beer garden. The buildings around the second inner courtyard of the Order Castle and the cloister are partly used by the monastery museum.

Building history

Finds of individual wattle stones and relief slabs suggest a Carolingian church was founded in the late 8th or early 9th century. Neither the time of its construction nor its form and location could be clearly clarified until today. Also of the first monastery church, which was built around 1070 or soon after, there are no more secure remains to be seen. What is certain, however, is that in the second half of the 11th century, before the construction of the monastery, two churches already existed in Millstatt, which were owned by the Count Palatine Aribo II († 1102).

Medieval Benedictine monastery

The period from 1122 to 1200 is assumed as the construction phase for the successor building of the “Aribonian” monastery church. The Domitian's Vita recorded by the first abbot Otto shows that the nave, closed in the east with three apses , was built after a devastating fire. The second Millstatt abbot, Heinrich I, had his builder Rudger add a massive, initially open porch with a pair of towers to the church on the west side. The Romanesque gate with the gemstone was built around 1170. On June 4th, 1201 an earthquake hit the epicenter in the Liesertal Upper Carinthia. Collapsing buildings from Millstatt are not explicitly reported, but greater damage can be assumed. The vestibule lost its original character by bricking up the round arches and the entrance portal by an architrave pushed under the tympanum .

To the east of the then chapter house, a Marienkapelle, today's Domitian's chapel, was added. Other parts of the Romanesque architectural style that are still visible today include the cloister, in particular the church portal with its arched relief, the vestibule of the collegiate church with its sculptures and some figures on the outer gates, which have now been walled up.

After a major fire that must have taken place between 1288 and 1290, the monastery building was rebuilt in 1291 under Abbot Otto IV. In the case of the damage caused by the strong earthquake of January 1348 , which among other things resulted in a landslide on the Dobratsch , no damage reports from Millstatt have survived. Presumably, however, the westwork was completely closed at that time and the arch opening of the northern vestibule was made smaller.

Conversions for the Order of St. George Knights

In 1469 the St. George Knights took over the monastery. The most important task was the expansion of the monastery complex into a fortress. To the west of the old monastery building, they built a monastery palace that includes a two-story arcaded courtyard . A total of four protective towers were also built, two of which were built on the west side of the newly built castle and two on the front of the monastery in the south. Two relief stones with Siebenhirter's coat of arms and the year 1497, which were placed on the first floor of the southern front of the monastery, indicate the year the construction work was completed.

The church was also redesigned under the Knights of St. George. In 1490 Johann Siebenhirter had a rectangular chapel with a star rib vault and - fifteen years later - a mirror-like counterpart (today's Geumankapelle) built on the south nave. During this time, the south or cloister portal was created from various Romanesque sculptures. Between 1510 and 1519, Grand Master Geumann had the three originally Romanesque round apses in the Gothic style replaced by higher choir closings. Furthermore, the entire church was provided with star rib vaults.

Reforms of the Jesuits

In contrast to the Knights of St. George, the Jesuits have not changed much of the structure. Today's Annakapelle was added to the north aisle (1632) and in 1633 the relics of Domitian and his high grave were transferred to this chapel. In 1648 the collegiate church was refurbished, with most of the frescoes whitewashed and colorless windows inserted. Old statues, altars, chairs and the pulpit have been removed and replaced with furnishings in a lively, baroque style; The showpiece of the new furnishings was the new high altar . In 1670 the towers were given the onion shape characteristic of the Baroque era.

A decisive event for the Millstatt Jesuit residence was the tremendous earthquake with almost three weeks of aftershocks in 1690. The Litterae Annuae of the Jesuits report: “At five o'clock in the afternoon, while Vespers was being sung, the earth trembled in the whole area with infernal underground noise of a tremor such as had not been heard for centuries. The brick portico for the ships on the lake side collapsed with the first impact. A stone pillar fell from the tall towers. There were considerable gaps in the towers themselves. ” Repairing the earthquake damage took four years and required extensive renovation work on the collegiate church and the monastery buildings. The damage to the tympanum, which was plastered between 1691 and 1878, can still be seen today, particularly on the architrave. This marble bar, broken into four parts, no longer supports the relief, but is held by it with iron clips.

After the monastery was closed in 1773, parts of the buildings fell into disrepair under state administration in the 19th century. Some of them were used as workshops, storage and unloading areas, and some were dismantled or rebuilt. The Carinthian historian Gottlieb Freiherr von Ankershofen cleared the cloister in 1857 and had the buildings subjected to a scientific assessment by JE Lippert, which was published in 1859. Since then, restoration measures have been carried out continuously, including overpainted late Gothic frescoes in the collegiate church and in the cloister.

The interior of the collegiate church was last restored in 1988/89, whereby building inscriptions of the St. George knights were preserved, the last exterior restoration in 1991/92 was mainly the appearance of the tower front.

Building description

The monastery complex is divided into the ensemble of the church (1) and the chapels attached to it in the northeastern area (2–5), a building wing built in front to the south (9 today: Lindenhof) and the building wings of the Order Castle (7, 8, 10) in the west . The cloister (6) connects to the south of the church. The two inner courtyards, each characterized by a large linden tree in their middle, are embedded between the wings of the building ; the so-called 1000-year-old linden tree in the lower courtyard used to be used as a court tree .

Church and chapels

Church of St. Salvator and All Saints

The former collegiate church and today's parish church (1) is a three-nave pillar basilica originally built in the Romanesque style . It measures 66 m in length and 21 m in width, but is only 12 m high at its highest point due to the later retracted vault.

The entrance to the churchyard in front of the west portal of the church is lined with a portal with frescoes from around 1490 to 1500, which presumably come from the school of the painter Thomas von Villach . To the left of the churchyard portal is a late baroque wayside shrine with a carved crucifixion group, which was created in the first half of the 18th century. To the right of the portal, a war memorial was also designed as a wayside shrine in 1932. Between the churchyard portal and the church, along the north wall and behind the building, there is a cemetery that was abandoned in 1953, but is still maintained today. The churchyard is closed off by a defensive wall, the loopholes of which date from the time of the Knights of the Order.

The massive west building of the church was built in the last third of the 12th century. A legend in the door shows that Abbot Heinrich I, who headed the monastery from 1166, was the client of the west building including the vestibule, the portal and the pair of towers. On the two-storey substructure of the building are the two towers, which were crowned with the onion roofs typical of the Baroque era around 1670 . The west portal, which was built around 1170 and was expanded in the 13th century, is rich in symbolic variety of forms with numerous motifs that were attached to ward off and banish demons. The left of the two door wings of the wooden door donated in 1464 bears the oldest depiction of the monastery or today's municipal coat of arms. The pillar architecture in the western section, which appears rather squashed in the interior, gives way to a higher and slimmer architecture of a relay hall in the eastern section .

The stained glass windows of the church were made by the Tyrolean glass painting company Innsbruck and used in 1912/13. The motifs mainly show half-length portraits of saints, alongside coats of arms of sponsors and ornaments of historicism . Along the aisle, pictures of the Way of the Cross are hung in neo-Gothic wooden frames.

In the northern apex of the choir is the cross altar, which was made of wood around 1770. The main picture of the cross altar shows a lamentation of the crucified, in the vault above a master builder's mark and the year 1518 can be seen. The high altar was made in 1648. Its main picture, which was made in 1826 by the Obervellach painter Johann Bartl, is framed by two monumental, gilded statues and shows several saints in veneration of the Trinity. The choir organ dates from the end of the 17th century and was originally installed in the church in Kreuschlach near Gmünd.

organ

The organ was built in 1977 by the organ builder Marcussen (Appenrade, Denmark). The instrument has 29 registers on three manuals and a pedal .

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Coupling : I / III, III / I, III / II, I / P, II / P, III / P

Anne Chapel

The Anne Chapel (2) adjoins the northern side choir. It was originally built in 1632 to hold the relics of Domitian. The chapel is a rectangular building with groin vaults and a 3/8 end and was designed with foliage stucco by Kilian Pittner in the early 18th century . The oval altarpiece shows Mariae's lessons. The wrought iron grille was erected in 1708.

Loreto Chapel

The Loreto Chapel (3) dates from the Gothic (14th century); in their place there was probably a chapel already at the time of the Benedictines. It was rebuilt at the end of the 17th century, based on the Casa Santa in Loreto . The entrance to the two-storey building is at the north choir, but the chapel is also accessible from the main church. The low main room has a pointed barrel vault, has no windows and is undivided except for the cornices around the sides. On the Altarmensa there is a carved statue of the Black Mother of God with Child (around 1700) and two late baroque reliquary showcases. The access to the walled choir of the original Gothic chapel is behind the altar. The choir has a 5/8 end , cross ribbed vaults and three pointed arch windows.

Domitian's Chapel

The core of Domitian's Chapel (4) consists of Romanesque walls and was rebuilt under Grand Master Geumann (1508–1533) and then redesigned several times (1632, 1641/42, 1716). The chapel is a three-bay, wide room with a ribbed vault, the pillars of which are covered in baroque style. There are four pointed arch windows. The gallery in the western yoke has a swinging rococo armor. The choir consists of a front yoke and a 5/8 end and is higher than the nave. It has a star rib vault. At the end of the choir there are three pointed arch windows.

The altar is dated 1716 with a chronogram. It is designed in light column architecture with swinging side panels. In these there are sacrificial passage portals at the bottom and two bishop figures at the top. In the middle of the altar is the glass shrine (1643) with the bones of Duke Domitian and his wife. Above the shrine is a picture depicting Domitian's ascent into heaven.

The pulpit dates from the Rococo (around 1770). The triumphal arch has a cartouche with the inscription "Honori et Gloriae Beati Domitiani" and a chronogram 1716 at the top .

The nave of the chapel has four free-standing pillars, above which are oval oil paintings flanked by putti (1720). The pictures show the miracles of St. Domitian and show views of Millstatt and Spittal an der Drau. Immured in the west wall is Domitian's tombstone, originally the cover of a tumba, marked 1449. The stone shows “Duke Domitian in knight armor with ducal hat and cloak standing on a lion, on the right the fief flag with the combined arms of Carinthia and Palatinate / Bavaria , the same coat of arms on the shield ”.

Seven Shepherds Chapel

The Siebenhirterkapelle (5) adjoins the north aisle of the church. It was built around 1500 and has a star rib vault. The altar of Mary dates from 1650 and contains a picture of the Mother of God presenting the rosary to St. Dominic. The tombstone of Grand Master Johann Siebenhirter is on the wall under the window. The tombstone is made of red Adnet marble and was made by the Augsburg sculptor Hans Bäurlein (around 1500). The font is probably late Gothic and has a Baroque tower from the third quarter of the 17th century. In the floor there is a tombstone of Countess Chuniza from the 12th century. The Millstatt Jesuit Crypt is located in the basement of the building, also known as the Corpus Christi chapel.

Geumann Chapel

The Geumann Chapel was built in 1505, which is evidenced by an inscription in the arch . Its reticulated vault is covered with tendril paintings. The baroque Johannes altar is marked 1650, above the altarpiece, which shows the baptism of Christ in the Jordan, a Johanness bowl with the head of the Baptist is attached (around 1520). The tombstone of the eponymous Johann Geumann († 1533), embedded in the south wall, is an epitaph made of white marble. It was made by the Salzburg sculptor Hans Valkenauer and shows the second Grand Master of the Knights of St. George in life size in full armor standing on a lion. In his right hand he holds a flag with the prince's crown as well as the coat of arms of the order, the Millstatt residence and the Geumann family from Upper Austria .

Johann Geumann (* approx. 1467; † December 23, 1533) was a son of Heinrich VI Geumann and married to Margarethe von Trautmannsdorf . Carer in Maria Lankowitz and Voitsberg . Belonged to the will executors of Emperor Maximilian I. After the death of his wife in 1495 a member, 1499 commander, 1508 administrator and from 1513 second grand master of the Order of St. George , based in the Millstatt Monastery. Brought 8,000 guilders private wealth into the order. He died of the consequences of the plague in Gmünd / Carinthia and is buried in Millstatt. On his marble tombstone he had Hans Valkenauer portray himself in full armor before 1518. The surrounding inscription has the following wording: “ Here, the reverend prince buried Johan Geüman / the other high maiste Sant Jorgen / ordē.s donate the eternal mess and this capell died in / 15… jar dem got grace ”. Parts of the Abbey Church in Millstatt still bear witness to his building activities as a monastery superior: parts of the Gothic ribbed vault, the baptismal font with the Geymann coat of arms, the Geuman chapel and the Renaissance arcades in the courtyard. A panel (created after 1508) in the Landesmuseum Klagenfurt shows him kneeling with his family in front of the Mother of God.

More monastery buildings

The former monastery complex is located south of the church. The entire complex is grouped around two courtyards and the cloister.

The cloister

Main article: Millstatt cloister

The cloister (6) is a rectangular complex. The wing adjoining the church is one-story, the other three are two-story. Towards the courtyard there are coupled arched windows with a central column. In the north wing there is a pointed arch portal, in the east and west wing there are baroque round arch portals. The vaults are star ridge vaults from around 1500, in the south wing there is a jumping vault.

The cloister portal is located in the northeast corner and used to be the monk's gate to the church. It was redesigned around 1500 using high Romanesque sculpture. Two former pillar figures, probably from the rood screen that was removed at the time , now serve as lintel atlases: St. Paul on the left, the Archangel Michael on the right, both from the second half of the 12th century. Two free columns support the vault of the cloister corner. In the cloister there are some wall paintings from the 15th and 16th centuries, such as a Madonna and Child, scenes from the legend of St. George and a Madonna with saints.

Order castle and inner courtyards

The buildings of the Order Castle (7) around the rectangular upper inner courtyard date from the 15th and 16th centuries, although the core of the wall is much older. The wings of the two building wings are two-story. The arcade in late Gothic style was built under Grand Master Siebenhirter, it has groin vaults and round arched arcades. On the west and south wings there are two-story Renaissance arcades (around 1530), with late Gothic pillars on the ground floor and Ionic columns on the upper floor. The arcade columns in the west wing have romanized cube capitals. In the upper passage to the inner courtyard there are three Carolingian wickerwork stones from the 9th century, which were probably part of the first Millstatt church.

Hochmeisterschloss (today: Lindenhof)

At the site of the current building there were farm buildings of the monastery as early as the 13th century. The former Grand Master's Palace (see Plan No. 9) (today: "Lindenhof") is a four-storey wing of the building, flanked by two of the four defensive towers of the monastery complex, the basic substance of which dates back to the 15th century. On the west tower of the building there is a coat of arms above the gate of the then Grand Master "Johann Siebenhirter" (first Grand Master of the Order of St. George (Austria) (active 1469–1508)) with the year 1499. The entire south wing of the Grand Master's Palace was designed by a Viennese Advokaten converted it into a hotel that opened in 1901 and was used as the “Grandhotel Lindenhof” until the 1970s. In the courtyard there is an (allegedly) 1000-year-old linden tree, which was planted when the monastery was founded and dominates the courtyard The top floor was not added until the hotel was converted in 1901, and in the same year the east tower was renewed after a fire and the crumbling defensive walls to the south of the building were removed. The hotel rooms have remained largely unused for more than a quarter of a century since the 1970s. to revitalize and renovate the Lindenhof and to set up a restaurant, gallery, shops, offices and apartments there , have now been put into practice (as of 2018).

Stiftsarkaden and arcade courtyard, Stift Millstatt

The old monastery arcades are located in the inner courtyard north of the entrance to the cloister (see plan no. 10). The 2-storey arcade courtyard, built in the Renaissance style, was built in the 15th century at the time when the Order of St. George (Austria) was given the Millstatt Monastery as its headquarters (from 1469). The 500-year-old linden tree in the courtyard was probably planted at the same time. The arcade courtyard forms a characteristic ensemble in the area of the monastery grounds.

Stiftsmuseum

Main article: Millstatt Abbey Museum

The Millstatt Abbey Museum was founded in 1981 by Franz Nikolasch . It provides an overview, in particular of the history of the monastery, but also of the development of the Millstatt market and its surroundings. The museum houses numerous original works and facsimiles from the time of the Benedictines, the Knights of St. George and the Jesuits. Below is a prayer book by Maximilian I with drawings by Dürer , Altdorfer and other artists. In a dungeon cell, scribble inscriptions on the walls allow conclusions to be drawn about their use in the first half of the 16th century. One area of the museum is dedicated to the Neolithic and Bronze Age finds from the area around Millstätter Berg , with the consecration altar to a water deity, the depiction of the excavations of the early Christian church in Laubendorf and the ramparts on the Hochgosch near the Egelsee . Another section shows minerals, ore deposits, mining facilities and processing facilities that are related to Millstatt. The history of magnesite mining on the Millstätter Alpe is presented in great detail .

Art historical features

Millstatt Library and Millstatt Manuscript

Main article: Millstatt manuscript

The choral prayer , which determines the daily routine of the monks, always requires liturgical books such as psalteries , breviaries , lectionaries , legends of saints or missals . New foundations of a monastery received the initial equipment from the mother monastery. Benedictines in particular needed an extensive library, as the rules in Lent also prescribe private reading. There must have been numerous works in Millstatt, of which only a few have survived due to unfavorable circumstances. The earliest known Millstätter directory of the library from 1577 was only created after the dissolution of the Benedictine monastery.

Until the introduction of printing , books had to be copied by hand or bought. Although the walls of one of the oldest and most distinguished clerical houses in Carinthia never housed a well-known school, a high level of education can be assumed. In the first centuries of the monastery, magnificent medieval manuscripts were collected and produced in the library of the Benedictine monastery. A Nicolaus monachus et sacerdos Milstadiensis is known as the only writer of the Millstatt monastery community . A total of 191 manuscripts have been preserved from the Millstatt library, the seven oldest of which date from the 11th century. A Benedictionale from the 11th century is probably still part of the founding equipment. A liturgical calendar, the Millstatt Sacramentary , has survived from the 1970s .

The preserved holdings of the Millstätter library can be found today in the Carinthian State Archives (14 manuscripts), in the University Libraries Klagenfurt (99 Hs) and Graz (26 Hs, 40 prints), in the Austrian National Library (5 Hs), the Austrian State Archives (29 Hs , 23 prints), in the National Library Budapest, in London, Stockholm (Siebenhirter Breviary) and in private and public free float.

A particular stroke of luck is that the Millstatt handwriting has been preserved for the state of Carinthia. The History Association for Carinthia was able to buy the fragment , which is now in the Carinthian State Archives , in 1849. It is a partially illustrated manuscript written in Early Middle High German that was written around 1200. The first part, Genesis , is a rhymed, free translation of Genesis into German and is considered the oldest surviving German-language poetry in Austria. The authors of the individual parts of the collective manuscript probably did not come from the Millstätter pen, but rather the collective manuscript was created in the local scriptorium from the writings of several authors. However , it cannot be ruled out that at least parts of the work were created in the Benedictine monastery under Abbot Heinrich II von Andechs . Other noteworthy parts of the Millstatt manuscript are, besides the Genesis, the Physiologus , a medieval textbook on zoology, and the Exodus .

Last Judgment fresco

The so-called Last Judgment fresco in the collegiate church is an approx. 6 m wide and 4 m high fresco in the Renaissance style. It was commissioned by a supporting member of the Knights of St. George and made by Urban Görtschacher around 1519.

In the picture above, the judging Savior is shown on a rainbow, next to them Mary and John the Baptist as intercessors and the twelve apostles sitting on banks of clouds. In the lower half of the picture, trumpet-blowing angels call the dead out of the graves for the Last Judgment. On the left, the blessed, including Pope Leo X , Emperor Maximilian I, as well as bishops and cardinals, are received at the gates of heaven ; on the right, the damned are tortured by devils and dragged to hell on a chain.

Originally attached to the west facade of the collegiate church, the picture, which has meanwhile been heavily damaged, especially in the lower area, was transferred to the south wall inside in 1963. The original preliminary drawing is still in its original place, the west facade.

Millstätter Lenten Cloth

The Lenten cloth of the collegiate church, with around 50 m² of cloth surface (approx. 8.40 × 5.70 m), is one of the largest surviving canvas paintings in the entire Alpine region. In the Middle Ages it was the custom in many churches that a large cloth was pulled up in front of the high altar on Ash Wednesday and covered it until Holy Saturday. The Millstätter Lenten cloth was painted in 1593 by Oswald Kreuselius (also: Kreusel ) with watercolors. It contains 42 pictures, each 120 by 95 cm in size, showing twelve scenes from the Old Testament and 29 scenes from the New Testament. From the end of the 19th century, the Lenten veil was no longer exhibited because of the nude scenes and was brought to Klagenfurt in 1932, where it was used in the Christ the King's Church. It has been back in Millstatt since 1984, where it covers the high altar again from Ash Wednesday to the Wednesday of Holy Week.

References and comments

- ↑ Sigmund Herzberg-Fränkel (Ed.): Monumenta Germaniae Necrol. II , Berlin 1904, p. 457

- ↑ Herzberg-Fränkel 1904 p. 456

- ↑ Robert Eisler: The legend of St. Carantan Duke Domitianus . In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 28, 1907, pp. 52–116.

- ^ Claudia Fräss-Ehrfeld: History of Carinthia. The Middle Ages . Klagenfurt 2005, p. 153

- ↑ a b See on this Hans-Dietrich Kahl: Der Millstätter Domitian. Knocking out a problematic monastery tradition for proselytizing the Alpine Slavs of Upper Carinthia. Stuttgart 1999

- ↑ Axel Huber : earthquake damage to the Millstätter Stiftskirche , p. 343 f.

- ↑ Ibid. The abbot Gaudentius, registered in the Millstätter Nekrolog on January 27, resided in the monastery of Rosazzo in Friuli.

- ↑ Erika Weinzierl-Fischer: History of the Benedictine monastery Millstatt in Carinthia. 1951, p. 65

- ↑ Erika Weinzierl-Fischer 1951, p. 104

- ↑ Erika Weinzierl-Fischer 1951, p. 69

- ↑ Erika Weinzierl-Fischer 1951, p. 86 f. The land register from 1470 is in the National Library in Vienna as manuscript no.2859.

- ↑ Axel Huber: Reichenhaller salt for the Millstatt monastery. News from Alt-Millstatt. 5/2018. In: Der Millstätter: Information from the town hall; official notification from the market town of Millstatt. October, 2018 , pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Erika Weinzierl-Fischer 1951, p. 120 ff.

- ↑ The document is now in the Vienna State Archives

- ↑ Matthias Maierbrugger 1989, p. 119 f.

- ↑ Chronology at the Millstatt Abbey Museum

- ↑ Cf. Koller-Neumann: On Protestantism under the Jesuit rule Millstatt.

- ↑ Cf. Nikolasch: The Jesuit Order in Millstatt .

- ^ Matthias Maierbrugger 1989, p. 209

- ↑ Matthias Maierbrugger 1989, p. 31f.

- ↑ See Axel Huber, Seismic damage to the Millstätter Stiftskirche .

- ↑ Richard Perger: The work of the Jesuit order in Millstatt. In: Studies on the history of Millstatt and Carinthia. Lectures at the Millstatt Symposia 1981–1995. Archive for patriotic history and topography, 78. Klagenfurt, 1997, p. 542.

- ↑ Information on the organ

- ↑ Dehio Carinthia 2001, p. 544

- ↑ Michael Thun: Millstatt's Jesuit Crypt soon to be open to the public? meinviertel.at, February 2, 2016, accessed on October 21, 2019 .

- ↑ Karl Lind: Mittheilungen of the kk Central Commission for the research and preservation of the architectural monuments. ( Memento of the original from November 29, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Josef Alexander Freiherr von Helfert (Ed.), August Prandel, Vienna, 1868. p. 173 and appendix, panel II.

- ↑ Doberer 1971.

- ↑ From the Hochmeisterschloss to an exclusive residential project: the Lindenhof in Millstatt am See (Carinthia). In: bda.gv.at . April 2019, accessed July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Friedrich Koller: From the first guest to mass tourism. ( Memento from May 9, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Diploma thesis, Klagenfurt 2005.

- ↑ Information about the Lindenhof , requested May 21, 2018.

- ↑ Cf. Maria Mairold: The Millstätter Library. In: Carinthia I , 1980, pp. 87-106.

- ↑ Franz Nikolasch: Comments on the liturgical calendar of the Millstatt Sacramentary. In: Carinthia I, 2007, pp. 71-105. [with 12 colored facsimile]

- ↑ Axel Huber: The Millstätter Fastentuch . Johannes Heyn Verlag, Klagenfurt 1984, ISBN 3-85366-526-8 . Franz G. Hann: The Lenten veil in the church in Millstatt . In: Carinthia I, 83rd year, 1893, pp. 73–81.

literature

- Dehio manual . The art monuments of Austria. Carinthia . Anton Schroll, Vienna 2001, pp. 536-548. ISBN 3-7031-0712-X

- Wilhelm Deuer: Main parish church of St. Salvator and All Saints in Millstatt . Christian art places of Austria 274, Verlag St. Peter, Salzburg 1996. (without ISBN)

- Wilhelm Deuer: [Bibliography on the history of Millstatt]. In: Germania Benedictina, Vol. III / 2. The Benedictine monasteries and nuns in Austria and South Tyrol. St. Ottilien, 2001, p. 759 ff.

- Axel Huber: Earthquake damage to the Millstätter Stiftskirche - consequences for its building history. In: History Association for Carinthia: Carinthia I. Journal for historical regional studies of Carinthia. Volume 192/2002, pp. 343-361.

- Irmtraud Koller-Neumann: To Protestantism under the Jesuit rule Millstatt. In: History Association for Carinthia : Carinthia I . Journal for historical regional studies of Carinthia. 178th year. 1988, pp. 143-163.

- Matthias Maierbrugger : The story of Millstatt . Market town of Millstatt published by Ferd. Kleinmayr, Klagenfurt, 1964; exp. New edition: Carinthia Verlag, Klagenfurt 1989. (without ISBN)

- Maria Mairold: The Millstatt Library. In: History Association for Carinthia: Carinthia I. Journal for historical regional studies of Carinthia. Volume 170/1980, pp. 87-106.

- Erika Doberer: Inserted fragments on the cloister portal of the Millstatt collegiate church . In: Wiener Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte 24 (1971), pp. 49–58.

- Franz Nikolasch : The Jesuit order in Millstatt. Lecture at the jubilee festival of the Jesuits in Carinthia, Millstatt, September 16, 2006.

- Franz Nikolasch: Millstatt: Main parish church of St. Salvator and All Saints, Abbey Museum, Kalvarienbergkapelle: Diocese Gurk, Deanery Gmünd-Millstatt , Carinthia, photos by Gregor and Marcel Peda, published by the Catholic Abbey Parish (= Peda Art Guide , Volume 795). Peda, Kunstverlag Passau, 2010, ISBN 978-3-89643-795-2 (German, English, Italian).

- Erika Weinzierl-Fischer : History of the Benedictine monastery Millstatt in Carinthia (= archive for patriotic history and topography , volume 33). Verlag des Geschichtsverein für Kärnten, Klagenfurt 1951 DNB 455431558 , OCLC 8754889 (dissertation University of Vienna 1948, 144 pages, partly in Middle High German and Latin).

Web links

Coordinates: 46 ° 48 ′ 15 ″ N , 13 ° 34 ′ 15 ″ E