Great St. Martin

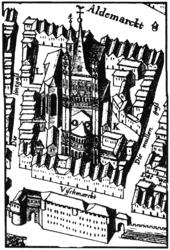

Groß St. Martin is one of the twelve large Romanesque churches in Cologne . It stands in the old town and is closely surrounded by residential and commercial buildings from the 1970s and 1980s. Until the secularization of 1802 the church was the abbey church of the Benedictine abbey of the same name . The three-aisled basilica with its shamrock-shaped east choir and the square crossing tower with four corner towers is one of the most striking landmarks in the city panorama on the left bank of the Rhine .

overview

The basilica was built in the 12th century in the Rheinvorstadt , a former Rhine island, on the foundations of Roman buildings. For several centuries it served as the abbey church of the Benedictine monastery of the same name until it was used as a parish church in the 19th century after the monastery was secularized . Air strikes during World War II wreaked havoc on the church. The tower was reconstructed until 1965 . The reconstruction work continued until 1985. The church was consecrated 40 years after the end of the war.

Since 2009, Great St. Martin has again been open to believers and visitors as a monastery church of a newly founded branch of the communities of Jerusalem . In the newly created crypt , excavations from Roman times can be viewed.

The designation "large" St. Martin distinguishes the basilica from the significantly smaller and possibly older market church , also dedicated to St. Martin , of which only the tower has been preserved and which is known as "small" St. Martin . Johann-Peter Weyer , Cologne city architect from 1822 to 1844, wrote:

“When the island was later connected to the mainland of the city by filling the river on this side, the church was given the name Gross St. Martin, around those of a parish church dedicated to the same saint, built on the bank of Oben Mauren, called 'little St. Martin' to distinguish. "

history

The history of Groß St. Martin is linked to the history of the associated Benedictine abbey, so that decisions by the abbey often also affected the church. Only a few documents or construction reports have survived from the founding time of the monastery and church, which is why the knowledge about the building is also based on archaeological findings and art-historical considerations.

Archaeological findings on previous Roman buildings

The area around Groß St. Martin originally belonged to a Rhine island east of the Praetorium, upstream from Roman Cologne ( Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium ) . Excavations in 1965/1966 and 1973 to 1979 revealed that it had been built on since the first century AD.

A walled plaza with a length of at least 76 m east-west and a width of 71.5 m was identified as the first development, with a 55.7 × 43.8 m, slightly recessed area and a 34 × 17.2 m and 1.7 m m deep water basin. No comparable plants are known north of the Alps. Since there is no information about its use, we can only make assumptions: The large area is interpreted as a sports field (palaestra) , the water basin as a swimming pool ( natatio ) or as a storage basin for fish and mussels used by Rhine fishermen. Another theory speaks of a sacred area, possibly also the location of the still unknown Ara Ubiorum .

In the middle of the second century, the area was raised by about 1.5 to 2 m and four three-aisled halls were built in the south, east and west. Their location directly on the banks of the Rhine, as well as their shape and arrangement, indicate their use as warehouses (horreae) for commercial goods. A wall on the north side delimited the new, approximately 7000 m² large square.

At least the fourth, the south-eastern hall, was also used after antiquity. A new screed was applied three times, covering the older one. The previously smooth sandstone pillars were subsequently provided with a profiled base, of which it is not clear whether it dates from Roman or early medieval times. However, shards of Pingsdorf ceramics enclosed in the screed date from the Carolingian era .

In addition, the stratigraphy (soil stratification) was examined in a long section along the central axis of the church in 1965/1966 . An abundance of medieval and modern burials were found to a depth of approx. 2 m below the church floor.

Assumptions for the foundation of the Martinskirche and false chronicles

There is no evidence of the founding of St. Martin before the 10th century; the Cologne historiographer Aegidius Gelenius mentions in his "Praise of the City of Cologne" (De admiranda sacra et civili magnitudine Coloniae ... - of the admirable, sacred and worldly greatness of Cologne ...) a possible origin in pre-Carolingian times. According to this, the missionaries Viro and Plechelmus, who came to the Rhine with Suitbert - who later became the abbot of the Kaiserswerth monastery - founded the monastery and church; in doing so they were presumably supported by Pippin the Middle and Plectrudis , the founders of St. Mary in the Capitol .

A Chronicon Sancti Martini Coloniensis , supposedly from the 13th or 14th century, was based on these founding theories and was considered a source for abbey and church history until the end of the 19th century: St. Martin was due to the Scot Tilmon , who in the Built a chapel in 690 ; Viro, Plechelmus and Otger turned it into a monastery in 708. The chronicle has consistently documented the names of the abbots from the earliest times and describes events such as the destruction of the monastery and church by the Saxons in 778, when Charlemagne was fighting on the Iberian Peninsula . After that, one of Karl's paladins , the Danish prince Olger , had the building rebuilt at his own expense with the help of Karl, and Pope Leo III. consecrated two altars during his second visit to Cologne (805). For the years 846 and 882, destruction by the Normans is reported, from which the monastery and church would have had difficulty recovering.

It was not until 1900 that Otto Oppermann exposed the entire chronicle as a forgery by Oliver Legipont , a Benedictine monk to St. Martin from 1730.

A founding of a monastery and church in Franconian times (5th to 9th centuries) cannot be proven, but is sometimes assumed due to the patron saint Martin von Tours , as he is considered the most popular saint of the Franks and most churches under this patronage in 7th to 9th centuries were founded.

Foundation of the monastery and construction of the monastery in the 10th to 11th centuries

The foundation mentioned in the Lorsch Codex by the Cologne Archbishop Brun (953–965) as a canon monastery in honor of Martin von Tours is considered to be certain today . Brun listed the Martinskirche in his will among the churches to be taken into account and gave it as a present during his lifetime the relics of St. Eliphius , who became the second patron of Great St. Martin; his relics were transferred from Toul to the newly founded monastery.

The Koelhoff Chronicle noted in 1499 that Archbishop Warin von Köln (976–985) had Groß St. Martin repaired:

"So quam he aries zo Coellen vnd better de dat monster zo the great sent Mertijn zo Coellen dat old and vnd what vnd begaffde dat rychlichen."

"So he came back to Cologne and repaired the cathedral to make the great St. Martin in Cologne, which was old and dilapidated, and gave it abundantly."

This also indicates a higher age. Archbishop Warin of Cologne (976–985) is said to have spent his twilight years in the monastery.

It is certain that Archbishop Everger (985–999) converted the monastery into a Scots monastery through donations in 989 , which was inhabited by Irish Benedictines ("Scots"). The introduction of the Scots in Groß St. Martin falls between the first Irish settlements in the Merovingian- Carolingian period and the congregation of Benedictine Scots monasteries that have been grouped around Regensburg since the middle of the 11th century .

Gradually, in the 11th century, the Scots were replaced by local monks. Archbishop Pilgrim of Cologne (1021-1036) is said to have been averse to the foreign monks and to have contributed to their replacement; the last Irish-Scottish abbot was, however, only Alvold, who died in 1103. From the year 1056 Marianus Scotus lived in Great St. Martin for some time, which is why it was assumed that he met a number of his compatriots there.

In terms of the building history, art historians suspect that the remains of the wall found during excavations below the north aisle wall, which extend into the first yoke of the existing building, belonged to a church built under Brun. The west wall would have been about 7 m further north. This would have corresponded to the width of the former Roman warehouse; it may also have involved the conversion of the warehouse.

The Vita Annonis reports that Archbishop Anno II (1056-1075) had an apparition of Saint Eliphius and then had two towers built. Presumably they were built as a double tower in the east choir.

The new Romanesque building in the 12th to 13th centuries

In 1150 a city fire destroyed the Rhine suburb, and the church of the Benedictine monastery was also affected. The exact extent of the damage is not known, but it is assumed that the fire was used as an opportunity to completely demolish the damaged structure. In a first construction phase, the trikonchos was built, the only part that has survived almost unchanged to this day, as the crossing tower, nave and west end were repeatedly rebuilt as part of later plans.

Archbishop Philipp I von Heinsberg consecrated the new building in 1172, which until then only consisted of the trikonchos; the nave was probably already under construction. The two-story Benedictine Chapel was added to the northern apse , and the body of Abbot Helias, who died in 1042, was transferred to it.

Until another fire in 1185, the eastern yoke of the nave was completed, and apparently the following aisle yokes on the south side as well. These hit the north wall of the older parish church of St. Brigiden located there , which presumably led to the indentation on the south wall of Groß St. Martin.

Another building report has been handed down from the time of Abbot Simon (1206–1211). The late monastery brother Rudengerus bequeathed, among other things, seven thalers and 30 denarii to purchase stones in his will .

In the middle of the 13th century, walkways and the niches of the triforium were carved out of the somewhat older walls above the side aisles. This achieved the desired ease. During this time the ship was lengthened by five meters and the two-bay vestibule was added to the west.

Developments after completion in the 14th to 17th centuries

After the completion of the basilica in the 13th century, hardly any modifications were made to the design until the 19th century. Restoration measures are an exception, some of which became necessary in the following centuries, especially at the Vierungsturm.

In 1378, for example, a fire destroyed the roof of the crossing tower, which was then renewed with the help of donated funds, albeit only poorly.

A severe storm caused further damage in 1434. Three of the tower's four gables were blown down. While one gable fell on the surrounding buildings of the fish market, two hit the vaults above the high altar. The vaults were soon repaired and a bell with the year 1436 was hung.

Reforms under Abbots Jakob von Wachendorp (1439–1454) and Adam Meyer (1454–1499) ensured a more stable financial situation for the Benedictine abbey. This also benefited the interior of the church, which was enriched by some valuable pieces. The figures of a cross altar from 1509 are still preserved today.

Instead of a new gable, the tower was given its characteristic roof in the form of a gothic buckled helmet between 1450 and 1460 .

The statically unstable construction of the western flanking tower led in 1527 to the collapse of the south-western one onto the Magdalenenkapelle on this side, which was later completely demolished. The turret was initially not rebuilt.

The interior of Groß St. Martin has been decorated with numerous altars since the Middle Ages. These are likely to have fallen victim to an early baroque refurbishment in the 17th century, but nothing has survived today either.

18th century and influences from baroque and classicism

After Abbot Heinrich Obladen tore down the now dilapidated abbey building and replaced it with a new building in 1707, he had the interior of Great St. Martin repainted and the church equipped with a new, larger organ. The decorations bore the signature of the Baroque. For example, there were golden ribbons on the columns, domes and walls, and the interior was supplemented with four heavy chandeliers and numerous jewels and pieces of equipment.

The second half of the 18th century also brought a number of changes to the interior design and furnishings, some of which were already criticized by contemporaries. Abbot Franz Spix, who headed the Benedictine abbey from 1741-1759, had the area of the crossing altar increased by two to four feet and moved the altar to the rear apse . The aim was probably to make the Holy Mass more splendid . The fact that the abbots' old grave slabs were destroyed during this measure and that the pillars and pillars now protruded from the ground without a base did provoke criticism, for example from Oliver Legipont, but could not be prevented despite protest notes to the papal nuncio in Cologne.

Around 40 years later, at the end of the 18th century, Ferdinand Franz Wallraf was commissioned with the contemporary decoration of the basilica. On the one hand, Wallraf's program was still clearly Baroque, but it was also influenced by the incipient classicism . Side altars and pulpit were kept extremely simple, but the high altar was painted quite opulently, with clear echoes of the Greco-Roman world of gods.

“The victory of the New Covenant over the old man was illustrated on it by an accumulation of symbols: on a large basin, the 'sea of iron', lay bread that fell from an overturning table, skulls of sacrificial animals, censer etc. Angel held the broken seven-armed candlestick; the cross rose above the ark. On the front of the tabernacle an angel tore the curtain of the temple, inside the tabernacle the Savior himself was depicted. "

Even though Wallraf's pictorial program was later passionately criticized by representatives of historicism and the Catholic renewal movement of the 19th century and rejected as "pagan", from an art historical point of view it is now assessed as "extraordinarily successful".

In addition to the changes to the interior, the decision was made in 1789 to demolish the dilapidated northwestern flanking tower. Up until the middle of the 19th century, views show Groß St. Martin with only the two remaining eastern turrets. Other structural measures concerned the main apse, some of which were provided with windows, and the Magdalen Chapel between the southern apse and aisle, which was completely demolished.

Secularization and restoration work in the 19th century

From 1792, revolutionary France waged war against a coalition of European governments, including Austria and Prussia. In October 1794, the revolutionary troops took Cologne, ushering in a period of 20 years of occupation, which was to tear the city away from medieval traditions and customs and which was strongly anti-clerical from the beginning. The Archdiocese of Cologne ceased to exist in 1801, and Cologne Cathedral became a normal parish church. With the decree on secularization of June 9, 1802, all clerical corporations of the Rhine departments were abolished. The Martinskloster dissolved as a result of this directive on September 21, 1802, and the remaining 21 monks had to look for a livelihood outside the monastery walls; 11 of them took over pastoral positions in Cologne. The church of St. Brigiden was sold in 1805 except for the tower. In an auction protocol for the "sale of national goods" of the 11th and 25th Frimaire of the year 14 of the French revolutionary calendar it was stated:

"18th The former parish church of St. Brigitta in Cologne, adjoining the parish of the great St. Martinus on one side and unsuitable for worship. Suspended 600 Fr. (came to 5075 Fr.). "

The church was demolished and its remains were used as an organ staircase from 1812. From now on St. Martin acted as a parish church with the former abbot Felix Ohoven as the new pastor.

In the following years, the abandoned abbey building was initially used by some of the former monks and, since 1808, French veterans as living space. The increasing dilapidation of the buildings led to their evacuation in 1821 and partial demolition by the city in 1822. The cloister remained until 1839 when it was also abandoned. During a two-day visit by Victor Hugo to Cologne as part of his trip to the Rhine, the poet witnessed the last demolition work:

“When looking at this beautiful night picture my mind fell into a melancholy daydream: the city of the Teutons has disappeared, the city of Agrippa is no longer, the city of St. Engelbert is still standing. But for how long? [...] Today I saw the last rotten stones of the Romanesque cloister of St. Martin fall, which is supposed to give way to a café à la Tortoni [...] "

Overall, Groß St. Martin was a rather bleak sight towards the middle of the 19th century. The two western flanking towers were still missing, and the north side, on which the abbey buildings had previously been attached, was unadorned and had practically no windows.

Since 1843, the city of Cologne contributed financially to the restoration of the church. A new sacristy in Romanesque forms by Johann Peter Weyer on the north apse and the new aisle wall were among the first works. In 1847 the north-western flanking tower was added again. Heinrich Nagelschmidt's plans to extensively restore the entire basilica have been implemented since 1861. Here, too, the city of Cologne assumed half of the restoration costs of around 32,000 thalers. Groß St. Martin received a new roof, a renewed west gable, new windows in the south aisle and finally the fourth flanking tower again by 1875. The vestibule was cut in half.

The interior of the church should also be renewed. August Essenwein , director of the Germanisches Museum in Nuremberg, who was entrusted with the task, rejected the classicist painting from the end of the 18th century and tried, in the spirit of historicism , to embellish the authentic imagery of the Middle Ages with the decoration of the vaults, walls and floor .

“If you want to equip a medieval church again or decorate a work of art in the sense of the Middle Ages, you have to round off a small one from that large circle into a spiritual poem. It is only to be noted that [...] the time in which the church came into being has to be taken into consideration and the cycle of pictures has to be composed in the spirit of that time. "

Essenwein was aware that his project would only be realized step by step for material reasons. Therefore, as part of his uniform overall concept, he designed individual picture cycles for each part of the church, which could stand on their own. The work should proceed from east to west, from the essential to the less essential , and finally the floor should be shaped.

The three main rooms of the basilica, vestibule, nave and trikonchos, were to show the entire history of salvation from west to east in great detail and detail. Traditionally, the vestibule with its (still) two cross vaults was supposed to represent paradise. Eight motifs were planned from the creation story to the fall of man and the expulsion from the Garden of Eden. When entering through the church portal, a lamb symbolized redemption.

In the nave, human life and the world as well as the relationship between man and God and the saints were presented in all their facets, as well as the old covenant in chronological order , i.e. the period between the Fall and Christian redemption. The first vault contained allegories of the changing times, the second was dedicated to earthly space and its creatures: elements, weather, plants, animals. In the third yoke, the extraterrestrial, infinite space presented itself to the viewer, the sun, other stars and celestial vaults, plus signs of the zodiac and moon phases. The pillars also adorned images of those secular rulers who had made a contribution to spreading the Christian faith, Constantine the Great , Charlemagne , Godfrey of Bouillon and Baldwin of Flanders . Along the side aisles there were motifs from the life of the saints who were particularly venerated in this church.

The decoration of the intermediate yoke was intended to act as a mediator between the representations of the nave and those of the chancel: Divine grace was supposed to pour figuratively from the vault on the people, the floor represented the three continents known in the Middle Ages.

In the chancel, the cycle of images closed in the crossing and the apses with the representation of the whole divine glory with the Trinity, choirs of angels and the heavenly Jerusalem of the Revelation of John .

The large decoration plan was implemented in a modified and simplified form since 1868 by the Cologne painter Alexius Kleinertz . For example, the plans for the vestibule were not implemented. The raised chancel was brought back to its original level, a new organ and new furniture were purchased. In 1885 the work was completed.

The last major works of the 19th century concerned the rows of houses around the east side of the basilica, which were torn down in 1892 to create a clear view of the clover leaf choir, as well as the tower roof, which was given a new spire in 1894.

Destruction by air raids in World War II

Except for some security work in the years 1909 to 1913, of which a memorial plaque on the north aisle reminds us today, Groß St. Martin was essentially preserved in the state of restoration described in the 19th century until the Second World War.

Five of the numerous air raids on Cologne between 1940 and 1945 caused significant damage to Groß St. Martin.

During the British Operation Millennium , the first thousand bomber attack in war history on the night of May 30th to 31st, 1942, the roof of the tower and nave was completely burned, and the sacristy building on the north apse, which housed many old furnishings, was destroyed. At the beginning of 1943 the damaged basilica was given a temporary roof and the sacristy was also rebuilt.

In one of the heaviest area attacks on June 29, 1943, the so-called Peter and Paul attack , which killed 4,377 people in Cologne, and a bombing in October 1943, the damage to Groß St. Martin was comparatively small; the Benedictine chapel on the northern cone as well as the glass window and door were destroyed.

Due to the air raid on January 6, 1945, the dwarf galleries of all three apses collapsed almost completely. The walls of the crossing tower were badly damaged by a direct hit, of the four flanking towers only the northeastern one remained intact. The nave and choir vaults had largely been preserved until then.

The last major air raid on March 2, 1945 caused the most devastating damage. When the American troops marched into Cologne on the left bank of the Rhine four days later, only the lower part of the trikoncho and the side walls of the nave remained; The crossing tower and the stub of the flanking towers protruded from the old town, which was 95 percent destroyed. Almost all the vaults were perforated or collapsed.

Although the most distinctive landmark of the Cologne city skyline next to the cathedral was an overall desolate sight, a more detailed analysis of the structural damage revealed a better picture than expected. The art historian Franz Wolff-Metternich assigned the basilica in 1947 to the group of only "moderately damaged churches" in Cologne. A building inspection by experts in 1946 showed that restoration was less of an artistic problem than a technical one.

Reconstruction and restoration

Whether and how to rebuild Groß St. Martin was already a controversial discussion in the first post-war years. Should the ruins remain unchanged as a memorial , should something completely new be created or the old condition restored? And which condition was the one worth preserving, the "original" one? The latter question related in particular to the design of the interior of the basilica. The historicist decorations by August Essenwein from the 19th century, some of which were preserved, were considered by some to be a stylistic and technical mistake.

A series of lectures in the winter of 1946/1947 on the subject of “What will happen to the Cologne churches?”, In which well-known politicians, artists, preservationists and architects took part, reflects the debate. Arguments that a faithful replica of the state before 1939 would result in a cheap Colonia Aggrippinensis Attrapolis , a "fictitious world" full of "annoying copies" ( Carl Oskar Jatho ), raised considerable reservations, in particular rebuilding the tower of Great St. Martin. Otto H. Förster , the head of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum at the time , is often quoted:

“We want to close the vaults again in St. Martin, but fail to conjure up the tower again too quickly. It is much better if he stands still for a while as a stump and reminds others after us of what we had and why it was taken from us - until, perhaps in a hundred years, the day comes when a great master plans the tower for us that is as beautiful or more beautiful than the one before. "

However, the skeptics of reconstruction did not prevail. Under the direction of the architect Herbert Molis and the structural engineer Wilhelm Schorn , the first reconstruction and security work began in 1948. By 1954, the Konchen received their dwarf galleries, temporarily bricked, back.

From 1955 the reconstruction of the nave began, which was provided with a west wall and roof again until 1971. Since 1961, the Cologne architect Joachim Schürmann has been responsible for the further renovation of the building and furnishings. His concept is considered to be decisive for the current state of the church. The crossing tower had its old shape in 1965, making Cologne an important landmark.

Groß St. Martin probably owes the preservation of the interior painting from the 19th century to the reconstruction, which spanned over 40 years. While this was still under criticism from monument preservationists and art historians in the middle of the 20th century, there was a change in the appreciation of the historicist era in the 1970s and 1980s. Artists and restorers of the 19th century finally resorted to the surviving relics of the Middle Ages and shaped the room into a new image of what they understood to be “completely in the medieval spirit”. Today Groß St. Martin is the only one of the Romanesque churches in Cologne with preserved painting fragments from the 19th century. However, one could not and did not want to make a decision to complete the painting of the interior again.

After the new floors were laid between 1982 and 1984, parts of Essenwein's floor mosaics have also been preserved, and the interior fittings have been restored, Groß St. Martin reopened to the public for the first time in 40 years on January 13, 1985. The altar consecration on June 22nd was done by the Archbishop of Cologne, Joseph Cardinal Höffner . On this occasion he deposited relics of Saints Birgitta of Sweden , Sebastianus and Engelbert of Cologne in the sepulcrum relics of the altar.

Usage today, religious life and customs

One of the reasons for the very long restoration time is given that there was no parish for St. Martin after the Second World War. It was dissolved after the Second World War and the remaining members were assigned to the parish of Cologne Cathedral . There was no driving force in other Cologne churches to restore the church service space as quickly as possible, and the focus was initially on the renewal of the tower as a focus in the cityscape.

Since the rebuilding until the end of 2007 / beginning of 2008, Great St. Martin was used by Catholic categorical congregations for services in Spanish , Portuguese and Filipino .

Communities of Jerusalem (Fraternité de Jérusalem)

A change occurred on April 19, 2009, when Groß St. Martin became a monastery again after more than 200 years. The church was handed over by the Archbishop of Cologne, Joachim Cardinal Meisner, to the Paris-based Benedictine community of the Fraternité de Jérusalem . This founded a new branch of her order with initially twelve friars and sisters. Since then, the basilica has been accessible from Tuesday to Sunday from Laudes in the morning to Vespers and church services in the evening.

The Förderverein Romanische Kirchen Köln e. V. gives guided tours in Groß St. Martin from time to time.

Building description

Great St. Martin is a three-nave pillar basilica with three and a half Jochen whose square choir is surrounded by three large semicircular apses, which together form a cloverleaf shape form ( triconch ). In east-west direction it is 50.20 m long with cones (internal dimensions), the central nave is approx. 10 m, the transept, i.e. H. in the cones from inside vertex to inside vertex 28.50 m wide. The ridge height is 29.30 m, the eaves height 21.10 m. A 75.20 m high tower (without crowning) rises above the square choir, which is flanked by four octagonal turrets.

Exterior construction

The exterior construction clearly shows a design principle of the Staufer Romanesque. The complexity of the shapes and structures increases horizontally from west to east and vertically from the base to the top tower floor.

Trikonchos and crossing tower

In the east, seen from the Rhine and the fish market, the tower and the trikonchos act as a structural unit. To the south, east and north - interrupted by the flat gables of the transept - are the conches with their hemispherical roofs.

Round shapes dominate the lower two floors. The cone and tower are surrounded by a wreath of flat-structured round-arched friezes supported on pilaster strips . A lower sacristy is attached to the northern conche . In addition, this conche opens to the northeast with a portal. The first floor is similar to the lower one, but the round arches are more pronounced. Instead of the flat pilaster strips, the arches on the cones are supported by round three-quarter columns, and three of the round arches open up as windows in each semicircle.

The transition from the two floors to the roof is formed by a panel frieze and an open dwarf gallery with small round arches, which optically form a horizontal band around the unit of tower and cone. The upward increasing depth of the structure, from flat pilaster strips over window arches to the complete opening as a gallery, comes to an end here.

Above the conical roofs, the curves are replaced by flat structures. The pointed gables of the transept and nave are structured with a rosette on their front side; to the right and left of it a small, quadruple-shaped window opens .

The octagonal flanking towers now protrude to the side of the gable feet. Your first floor extends to the eaves of the long and transept gables. At this height, the mighty crossing tower stands out from the overall structure and appears as a separate structure. The forms that appear up to this height, arched friezes with pilaster strips, arched windows with columns and column-supported, open galleries, can be found again and again in the rest of the building.

Directly above the top of the gable, a panel frieze and a round arch panel similar to the dwarf gallery surrounds all five tower elements, so that they look as if they are combined by a band. The round arches in the main tower are slimmer than in the octagonal areas of the flanking towers. The cornice above also runs around all five tower bodies and at the same time forms the transition to the last two floors of the crossing tower, which from here onwards with its facade recedes a little.

This facade also varies the construction elements of the basement floors. The high, rectangular areas are structured by pilaster strips with four or five round arches each on the upper edge, but also open inwards through a large, double arcade window . The continuation of these elements can also be seen in a simplified form on the surfaces of the corner turrets.

Where the facade ends through a cornice and the tower merges into its high pitched roof, the flanking turrets protrude freely into the air with two small storeys and end with a pleated pyramid roof. The previous motifs - plate frieze, blind arches and gallery - can also be found on these two floors in a reduced form.

Longhouse

The comparatively short nave extends with two narrow aisles from the choir towards the west.

The division into three and a half bays is reflected on the outside of the north side in the walls of the side aisle and the upper aisle: four high, narrow surfaces are structured with pilaster strips and arched panels. Three of the side aisle walls are provided with large round windows, while the areas above the upper aisle open with narrow, high round arched windows.

The south facade of the nave is unadorned except for the circular windows, as the parish church of St. Brigiden stood here wall to wall with Great St. Martin. The former structural unity with the older parish church can be seen most clearly in a double setback and a slight incline of the side aisle wall, which was caused by the tower of St. Brigiden; In addition, the outlines of the foundations of St. Brigiden are indicated in the cobblestones in front of and next to Groß St. Martin.

Even today, the view of the south side of the nave is predominantly obstructed, here is the International Center Groß St. Martin , whose gate only allows passage into a small inner courtyard and the south side entrance of the basilica.

The front of the nave is slightly asymmetrical. On the north aisle, the already well-known high round arched panels strive up along the verges, along the roof pitch of the aisle gable, the south facade is plain and without decoration.

While a tall, narrow tracery window with a late Gothic pointed arch opens in the north aisle , there are only two small round arched windows in the south. A large part of the facade of the central nave on the upper floor, which is also structured by arched friezes, is taken up by a group of three tall, slender arched windows.

The entrance to the central nave opens through a richly ornamented portal. A Gothic pointed arch is supported on four columns, of which the outer right is slightly asymmetrical with a greater distance from the portal. Three of the columns continue upwards in the pointed arch as an archivolt . Two of them are made of extremely filigree stone carving, and there is also a small lion figure on a pair of columns. The asymmetry of the west building goes back to the former vestibule at this point, which was not rebuilt during the reconstruction after the Second World War, but whose foundations are indicated in the floor.

inner space

There are different construction phases for the interior of the basilica. Parts of the nave opposite the Romanesque crossing tower clearly show Gothic influences. Overall, however, the components merge harmoniously without any breaks.

Longhouse

In the west, the central nave is initially supported by three broad Romanesque pillar arcades that open it up to the side aisles. A cornice running around the three central nave walls above forms the basis for the triforium on the upper floor: Here, three round column-supported Gothic arched arcades per round arch in the basement form the transition to the upper floor . A narrow walkway opens behind it.

The total of six areas of the upper aisle, i.e. the upper floor of the nave above the side aisle, each open with a large arched window.

The threefold division is continued on the west wall. In the basement, the portal opens in a group of round arches, the outer high, narrow niches of which form. Almost the entire area above the portal and the aforementioned cornice is formed by a large group of arched windows.

The three high, square yokes of the nave are supported by round pillars that continue from the cornice to the top of the yoke as thin bulges along the pointed arch shape of the vault.

The intermediate yoke to the east forms a transition between nave and choir, which is clearly different from the three western bays. It is rectangular in its basic shape, and here strong groups of round columns rise straight from the floor right up to the vault. A cornice, similar to that of the western yokes, is significantly lower than this. On the upper floor, the transition to the vault is also formed by an arched arcade, but unlike in the nave, this is still clearly Romanesque; the middle of the three round arches rises above the two sides.

A special feature of the intermediate yoke is the south-western column that bears the basilica's only carved capital. It shows the heads of a crowned man and a woman with braids, often interpreted as a representation of the legendary founder Pippin and his wife Plektrudis.

Aisles

As can already be seen in the exterior, the north and south aisles differ, as the older Brigidenkirche adjoined wall to wall in the south and influenced the structural form there. Both aisles open to the north and south with three large circular windows each; of the two side entrances, only the southern one is used today. In the north aisle there is a staircase with the entrance to the crypt and the Roman excavations.

The three square west bays correspond to the north and south, each with longitudinally rectangular groin vaults; the rectangular intermediate yoke, on the other hand, is followed by a square aisle vault. At first, it is not very noticeable on the long walls that the south aisle is narrower; on the other hand, the difference becomes particularly clear on the end wall in the west: While the wider north west wall is designed with a generous hollow similar to the central nave, the south-west side aisle wall is only a narrow niche. The tower of the Brigidenkirche stood here.

Choir

On the three eastern sides, three monumental round arches rise above the square floor area of the choir, with an edge length of around ten meters; these are almost the same height as the three storeys of the nave. The arches form the transition between the choir and the equally high, semicircular vaulted cones.

The canopy-like vaulted ceiling and the side arches are supported by high, strong groups of columns. A cornice runs halfway up, a little lower than in the intermediate yoke, along the outer walls and supports the arched arcades above. In these, a narrow arch alternates with a wider one for the window openings, three per apse. Just like in the central nave, a narrow corridor runs between the arcades and the window ledge, which leads in the intermediate arches of the choir to small stairwells in the dwarf gallery and in the rooms above the aisles.

The floor of the eastern apse is about nine steps higher than that of the rest of the choir, and from the north apse the large north portal and - via a narrow staircase - a barred door to the former sacristy, which is now used as a treasury, open to the northwest Usually inaccessible to the public. Hollow niches accompanied by columns run along the walls of the first floor of all three apses, in which angel figures are placed in the south. The niches in the north and east conches, on the other hand, are empty.

Furnishing

Little of the church's older furnishings had been preserved as early as the 19th century, and the majority of the altars, sculptures and art objects that existed up to the mid-20th century were destroyed in the war. Today's interior is made up of a few preserved objects from the 13th to 16th centuries, a number of purchased and donated items from different epochs, as well as some modern works of art from the 1980s. In the following, the most important are described in more detail and others are briefly listed (numbers in brackets indicate the respective position in the floor plan).

Remains of the Holy Cross altar

A cross altar, donated in 1509 by the Cologne mayor Johann von Aich , has changed its location several times. In Essenwein's design drawings from the 19th century, it still stands on the north wall, but without the stone climbing arch, which was presumably placed behind plaster. At the beginning of the 20th century, however, it is described on the central north pillar of the nave. In both cases, the crucifixion group is placed above the altar, while a burial group is placed as a substructure for the altar table.

Today the ensemble of the crucifixion group is back at the presumed original location in the west of the north side wall, where the stone arch was only rediscovered in the course of restoration work after the war damage; the burial group was housed a few meters to the right in a niche that was also exposed again at this time. (1)

Crucifixion group

The sculptures of the crucifixion group consist of the crucified Christ, his mother Mary and the apostle John . Of the figural decoration of the Gothic sandstone arch surrounding the group, only three small statuettes have survived, depicting Adam and Eve and probably a prophet; the rest of the arch is completely weathered.

Tilman van der Burch , one of the few Cologne sculptors and carvers of the late 15th century mentioned in a document, is considered to be the creator of the altar sculptures . His figure of Christ on the cross is anatomically accurate and designed with realistic details. The eyes are closed except for a small slit, the pain is evident on the face. The costal arches stand out clearly and the side wound is large and clearly visible. The figures of Maria on the left and Johannes on the right form a contrast in their postures. In the overall ensemble, however, the couple is well coordinated with one another, while Maria looks down in calm mourning, Johannes looks upwards with pathos in his gaze and gestures towards the crucified. (1)

Entombment group

The so-called Entombment Group, which, in addition to the dead Christ, originally comprised seven sculptures laid out as three-quarter figures, is stylistically assigned to the cross altar; one of the female figures has been missing since the Second World War. Since the figures of John and Mary are very similar in design and physiognomy to those of the crucifixion group, it is assumed that they come from the workshop of the same artist, Tilman van der Burch.

The dead Christ is shown here as well as on the cross altar with anatomical details such as protruding veins and clearly recognizable wounds on the crown of thorns. He lies in the center with his head tilted slightly to the left on a sheet that is held at the foot of Nicodemus and at the head of Joseph of Arimathea . Mary, recognizable by her simple blue robe, lifts the arm of the corpse slightly so that the crucifixion wound on the right hand is clearly shown. On her left, Johannes is the third male figure in the ensemble, drawn in a very youthful manner. While Jesus and the figures at the head and foot end are almost life-size, the busts of women and John appear much smaller so that they act as a background in perspective. The mourner who is closest to Mary is occasionally interpreted in literature as Mary of Magdala .

The originally three other female figures standing on the right from Maria, two of which have been preserved, as well as the two male sculptures at the head and foot end, stand out due to their very rich and detailed contemporary clothing. (2)

Staufer font

Directly in front of the crucifixion group there is a baptismal font made of light limestone , which due to its shape and ornamentation is one of the most interesting stone works from the first half of the 13th century.

The font has an elongated, octagonal base. On the outside, its edge is provided with a frieze of eight large water roses, which are evenly distributed over the different widths of the side surfaces and thus also run over the edges. Lion heads sit at four corners; A narrow acanthus frieze develops from their mouths , which forms the upper edge of the baptismal font.

The baptismal font had a copper lid until it was destroyed in the war; Today's modern bronze cover was made by the sculptor Karl Matthäus Winter from Limburg an der Lahn , who used it to turn scenes from the Old and New Testaments into a picture frieze.

It is believed that the baptismal font was originally taken from the older Brigidenkirche; this received a new baptismal font made of brass in 1510, and it is likely that the older piece was taken over in the Martinskirche. Some legends up to the 20th century said that it was originally a gift from Pope Leo III. have acted. (3)

Epiphany triptych

A triptych that hangs today on the north-eastern nave pillar probably comes from a workshop in the Lower Rhine region and was created around 1530. It shows three scenes from the childhood of Jesus, painted in the pictorial language of the Dutch Renaissance: in the middle the adoration of the kings, on the left Mary and Joseph in silent adoration of their son, and on the right side wing the circumcision of the baby Jesus.

The altogether 72 centimeters wide and 102 centimeters high picture is executed in oil on wood and comes from the original possession of Groß St. Martin as an abbey church. (5)

Further pieces of equipment in the interior

- Man of Sorrows : The almost life-size wooden figure from the 16th century may come from the same workshop as the crucifixion and entombment group (9)

- Sculpture of St. Eliphius : Created in the 12th century at the earliest, the sculpture shows the miracle of the church's second patron saint, who is said to have chosen the place of his own grave with his head in hand after his beheading. The figure was acquired in art dealers in 1986. (8th)

- Marian altar with icon : The icon from Central Russia is estimated to be in the 17th century; it is a gift from the builders involved in the reconstruction and comes from the art trade. (4)

- Way of the Cross : The 14 tablets from the beginning of the 20th century are from private hands; they are attached along the wall of the south aisle (no number)

- Sacrament altar with tabernacle : The modern tabernacle in the northern side altar was created - as well as the cover of the Staufer baptismal font - by the artist Karl Matthäus Winter in 1984. (6)

- Crossing altar with wheel chandelier: Another part of the modern equipment is the simple stone altar table, which also serves as a reliquary pulcrum. The stainless steel wheel chandelier hanging above corresponds to the diagonal of the altar table with a diameter of 4.20 meters. Both objects were designed by the architect of the post-war reconstruction, Joachim Schürmann . (7)

- Brigidenkapelle: In the west yoke of the south aisle, remains of the wall testify to the demolished parish church of St. Brigida, which shared part of the south wall with Great St. Martin since the middle of the 12th century. The remains of the wall can be found in a narrow niche in the west wall. Today it houses a baroque statue made of wood with a crook of the Irish abbess Brigida von Kildare , who spent her youth in a rural environment. The mosaic remnant from the 19th century, which is embedded in the floor here, fits well: depicting the biblical "seven fat cows". (11)

- Statues of the apostles Peter and Paul: placed in the hollow niches on the left and right, two life-size statues by Peter Joseph Imhoff flank the west portal. Their origin is unclear, originally the sculpture cycle probably contained 4 figures. (12)

- Modern wooden cross: In front of the mostly closed west portal on the floor, directly in front of the central aisle of the nave, lies the monumental, very abstract wooden cross, created by Franz Gutmann . It was originally intended for a meditation room in Siegburg Abbey; when the decision was made against it there, it found acceptance in Groß St. Martin. (13)

- Window cycle: As part of the restoration, the artist Hermann Gottfried designed a new window cycle for Groß St. Martin in the 80s, which, however, has not yet been fully implemented. Each of the three windows in the conches should be dedicated to one of the three patron saints: St. Eliphius in the north, St. Brigida in the south and St. Martin in the eastern apse . So far only the three east windows have been decorated with stained glass from the life of St. Martin. In contrast to the windows of the nave and the west windows, the east windows are mainly in bright red, contrasting colors. The motif of the six nave windows relates to the six days of the creation story; the three-part west window above the portal is about Maria .

- Only a very small remainder of the mosaics on the Hohenstaufen floor has survived. In 1982, like the remains of the Essenwein mosaics, it was integrated into the new Euviller limestone flooring designed by Margot and Joachim Schürmann. A fragment of a 13th-century frieze made of a lion with a three-way split tail adorns the floor in front of the east niche of the south aisle.

organ

After the reconstruction, a simple southern Italian cabinet organ from the 19th century replaced the large church organ that used to be on an organ gallery on the west wall.

Today's organ was built in 1987 by the Fleiter company (Münster) for the hospital chapel in Borghorst . built. In 2015 the instrument was realigned by the company Orgelbau Krawinkel and set up in Groß St. Martin a little more west than the previous instrument . The mechanical slider chest instrument has 21 sounding stops on two manual works and a pedal . For reasons of space, it has numerous transmissions and extensions . The game table is three-manual; the first manual is a coupling manual. The instrument is well suited for performing German and French organ music. It has the following disposition :

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Pairing :

- Normal coupling: coupling manual (I), II / P, III / P

- Sub-octave coupling: III / III III / I

- Playing aids : two swell kicks

- Effect register : Zimbelstern

Bells

During the Second World War, four church bells were destroyed in a tone sequence of 1 –es 1 –f 1 –ges 1 that was common at the time . In 1984/85, Florence Hüesker (Bell foundry Petit & Gebr. Edelbrock , Gescher) cast five bronze bells, which were financed by foundations. Due to the heavy rib and the suspension on wooden fittings in a spacious bell room, the bells develop a high volume of sound.

| No. | Surname | Ø (mm) |

Weight (kg) |

Nominal (16th note) |

inscription |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maria | 1,580 | 2,600 | c 1 ± 0 | UNI DEO ET SANCTAΣ MARIAΣ OMNIS HONOR ET GLORIA. (All honor and glory to the one God and Saint Mary.) |

| 2 | Martinus | 1,150 | 1,140 | f 1 +1 | PER INTERCESSIONEM SANCTI MARTINI DA PACEM DOMINE IN DIEBUS NOSTRIS . (Through the intercession of Saint Martin, give peace Lord in our day.) |

| 3 | Eliphius | 1,070 | 820 | g 1 +1 | SUM CAMPANA PII QUI NOS DEFENDIT SANCTI ELIPHII. (I am the bell of the pious Saint Eliphius who defends us.) |

| 4th | Brigida | 940 | 570 | a 1 +1 | UT IN OMNIBUS DEUS GLORIFICETUR. (May God be glorified in all things.) |

| 5 | Ursula | 750 | 307 | c 2 +2 | PROTEGE CIVITATEM TUAM UBI CUM SODALIBUS TUIS GLORIOSUM SANGUINEM REFUNDISTI. (Protect your city, where you and your companions have shed the glorious blood.) |

The four small bells (2–5) form the ringing motif Freu dich, you heavenly queen ( Praise to God No. 525), the four large bells ( 1–4) the sounds of the Westminster chime .

literature

- Paul Clemen (Ed.): The Church Art Monuments of the City of Cologne II (= The Art Monuments of the Rhine Province. ) L. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1911.

- Sabine Czymmek: The Holy Cross Altar of Mayor Johann von Aich in Groß St. Martin. In: Colonia Romanica. Yearbook of the Friends of Roman Churches Cologne eV Volume 1. Greven, Cologne 1986, ISSN 0930-8555 .

- Sabine Czymmek: The Cologne Romanesque churches, treasure art. Volume 2, Cologne 2009 (= Colonia Romanica. Yearbook of the Förderverein Romanische Kirchen Köln eV Volume XXIII, 2008), ISBN 978-3-7743-0422-2 , pp. 103–126.

- JG Deckers: Great St. Martin In: Guide to prehistoric and early historical monuments. Volume 38. Cologne II. Excursions: Northern city center. Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz (Ed.). Zabern, Mainz 1980, ISBN 3-8053-0308-4 , pp. 134-146.

- Karl-Heinz Esser: On the building history of the church Groß St. Martin in Cologne. In: Rhenish churches in reconstruction. Mönchengladbach 1951, pp. 77-80.

- Society for Christian Culture (ed.): Churches in ruins. Twelve lectures on the subject of what will become of the Cologne churches? Balduin Pick, Cologne 1948.

- Helmut Fußbroich: The former Benedictine Abbey Church of Gross St. Martin in Cologne. Neusser Druck u. Verlag, Neuss 1989, ISBN 3-88094-631-0 .

- Ernst Günther Grimme : The Evangelistar of Gross Sankt Martin: a Cologne picture cycle of the high Middle Ages. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau / Basel / Vienna 1989, ISBN 3-451-20481-9 .

- H. Hellenkemper in: The Roman Rhine port and the former Rhine island. In: Guide to Prehistoric and Protohistoric Monuments. Volume 38. Cologne II. Excursions: Northern city center. Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz (Ed.). Zabern, Mainz 1980, ISBN 3-8053-0308-4 , pp. 126-133.

- Jürgen Kaiser (text) and Florian Monheim (photos): The great Romanesque churches in Cologne , Greven Verlag, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-7743-0615-8 , pp. 126-139.

- Hiltrud Kier: The Romanesque churches in Cologne: Guide to history and furnishings. Second edition. JP Bachem, Cologne 2014, ISBN 978-3-7616-2842-3 , pp. 150-161.

- Hiltrud Kier, Ulrich Krings (ed.): Cologne. The Romanesque churches in discussion 1946, 47 and 1985. In: Stadtspuren - Denkmäler in Köln. Volume 4. JP Bachem, Cologne 1986, ISBN 3-7616-0822-5 .

- Hiltrud Kier, Ulrich Krings (ed.): Cologne. The Romanesque churches in the picture. Architecture · Sculpture · Painting · Graphics · Photography. In: Stadtspuren - Monuments in Cologne. Volume 3. JP Bachem, Cologne 1984, ISBN 3-7616-0763-6 .

- Hiltrud Kier, Ulrich Krings (ed.): Cologne. The Romanesque churches. From the beginning to the Second World War. In: Stadtspuren - Monuments in Cologne. Volume 1. JP Bachem, Cologne 1984, ISBN 3-7616-0761-X .

- Ulrich Krings, Otmar Schwab: Cologne: The Romanesque churches. Destruction and restoration. In: Stadtspuren - Monuments in Cologne. Volume 2. JPBachem, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-7616-1964-3 .

- Werner Meyer-Barkhausen: The great century of Cologne church architecture 1150 to 1250. EA Seemann, Cologne 1952.

- Peter Opladen: Groß St. Martin: History of an abbey in Cologne. In: Historical archive of the Archdiocese of Cologne (ed.): Studies on Cologne Church History. Verlag L. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1954.

- Peter Springer: Awareness of history and reference to the present. August Essenwein's equipment project for Groß St. Martin in Cologne. In: Hiltrud Kier, Ulrich Krings (eds.): Cologne: The Romanesque Churches in Discussion 1946/47 and 1985 (= Stadtspuren - Monuments in Cologne. Volume 4). Cologne 1986, pp. 358-385.

- Gerta Wolff: The Roman-Germanic Cologne. Guide to the museum and city. 5th edition. JP Bachem, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-7616-1370-9 .

- Walter Zimmermann: New observations on the building history of Groß St. Martin in Cologne. In: Walther Zimmermann (ed.): The art monuments of the Rhineland. Supplement 2. Studies on early Cologne city, art and church history. Fredebeul & Koenen, Essen 1950, pp. 105-140.

- Helmut Fußbroich: Groß St. Martin zu Köln, Rheinischer Verein für Denkmalpflege und Landschaftsschutz, Issue 301, 4th edition, Cologne 2012, ISBN 978-3-86526-082-6 .

Web links

- Church opening times

- Prayer times of the communities of Jerusalem in Cologne

- Digitized archives for Groß St. Martin in the digital historical archive in Cologne

- Romanesque churches in Cologne: Great St. Martin. In: Web presence Förderverein Romanische Kirchen Köln . Retrieved July 5, 2019 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ JP Weyer: Pictorial representations and historical news about the churches in Cologne. Volume VII 'The Abbey Church of St. Martin', 1852. Reprinted in Werner Schäfke (Ed.): Kölner Alterthümer. Kölnisches Stadtmuseum, Cologne, 1993, ISBN 3-927396-56-7 , p. 18.

- ^ A b Gerta Wolff: The Roman-Germanic Cologne , 5th edition, JP Bachem, pp. 242–245.

- ^ Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz: Guide to prehistoric and early historical monuments, Volume 38, Cologne II, Excursions: Northern inner city , JG Deckers: Groß St. Martin , Philipp von Zabern, Mainz, pp. 134–147.

- ↑ Max Hasak: The architecture. 11th issue: The churches of Gross St. Martin and St. Aposteln in Cologne. 1899, p. 10 ( Wikisource ).

- ↑ Otto Oppermann, Critical Studies on Older Cologne History I. The falsifications of Oliver Legipont… , in: West German magazine for history and art. 19 (1900), pp. 271–344 (not viewed)

- ^ Hiltrud Kier and Ulrich Krings (eds.): Cologne: The Roman churches. From the beginning to the Second World War. , Note 16, p. 443.

- ^ Koelhoff'sche Chronik. , P. 135r.

- ^ A b Paul Clemen: The Church Art Monuments of the City of Cologne II. P. 354.

- ↑ Helmut Fußbroich: The former Benedictine Abbey Church of Great St. Martin in Cologne. P. 4.

- ^ Anton Ditges: Great St. Martin in Cologne. A commemorative publication for the seventh secular celebration of the consecration of the church on May 1, 1872 , L. Schwann'schen Verlagshandlung, Cologne, p. 17.

- ↑ a b c Peter Opladen, History of an Abbey in Cologne, p. 61.

- ↑ Stadtspuren Volume 1, Rolf Lauer: Groß St. Martin. P. 433.

- ^ Anton Ditges: Great St. Martin in Cologne. A commemorative publication for the seventh secular celebration of the consecration of the church on May 1st, 1872 , L. Schwann'schen Verlagshandlung, Cologne 1872, p. 66.

- ↑ Verein Alt-Köln, Viktor Hugo's description of Cologne from 1839. Lecture by senior teacher H. Roth at the monthly meeting on October 5, 1905 in the Quatermarktsaale. JP Bachem, Cologne, p. 14.

- ^ A b Paul Clemen, Die Kirchlichen Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Köln II, pp. 362–363.

- ↑ August Essenwein, The interior decoration of the church Gross-St.-Martin in Cologne. Publishing house of the church board, Cologne 1866, p. 6.

- ^ Carl Dietmar, Werner Jung: Small illustrated history of the city of Cologne. 9th revised and expanded edition, JP Bachem Verlag, Cologne 2002, p. 265.

- ^ Walter Zimmermann: New observations on the building history of Groß St. Martin in Cologne. P. 135

- ↑ Helmut Fußbroich: The former Benedictine Abbey Church of Great St. Martin in Cologne. P. 8.

- ↑ a b Churches in ruins. Twelve lectures on the subject of what will become of the Cologne churches? Franz Wolff-Metternich , pp. 45-46.

- ↑ Such as the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin.

- ↑ Churches in ruins. Twelve lectures on the subject of what will become of the Cologne churches? Otto H. Förster , pp. 204-205.

- ↑ Peter Springer: Historical consciousness and reference to the present. in: Hiltrud Kier: Stadtspuren, Volume 4. P. 360.

- ↑ Catholic city dean of Cologne: Catholic church services in Cologne as of 2008 ( Memento from January 2, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Updated information on foreign language services exclusively on the information board in front of the church. Catholic Church website displays outdated information.

-

↑ Homepage of the communities of Jerusalem , accessed on August 3, 2016.

Cologne is getting a new monastery. Domradio , April 18, 2009, archived from the original on July 10, 2012 ; Retrieved August 3, 2016 . - ↑ Prayer times of the community in Groß St. Martin , accessed on August 3, 2016.

- ↑ Helmut Fußbroich, The former Benedictine Abbey Groß St. Martin in Cologne. P. 27.

- ^ A b Paul Clemen, Die Kirchlichen Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Köln II. P. 380.

- ↑ Helmut Fußbroich: The former Benedictine Abbey Church of Great St. Martin in Cologne. P. 26.

- ↑ www.kirchenkoeln.de

- ↑ Organ transfer and information about the organ on the website of the organ building company, accessed on October 6, 2017

- ↑ Information about the organ on the parish website, accessed on October 6, 2017 (PDF); Information about the organ on the website of the organ building company (as of October 24, 2018)

- ↑ a b Gerhard Hoffs, Bell Music of Catholic Churches in Cologne ( Memento from April 28, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 5.5 MB) pp. 108–115.

- ^ Cologne [D.] - The bells of Great St. Martin, plenum (tower photo). Retrieved December 13, 2019 (German).

Coordinates: 50 ° 56 ′ 19 ″ N , 6 ° 57 ′ 42 ″ E