Historic Cologne suburb of the Rhine

The historic Cologne suburb of the Rhine was built on a site off the fortified Roman city . This area, which only consisted of a few buildings around AD 300, is now illustrated by a reconstruction of the Roman Germanic Museum in Cologne . The evolving suburb of merchants owed its further development to become the city's most important trading center primarily to the privilege of market rights that the city lords had received. In contrast to the Roman period, when trade mainly took place on the military or highways, it now established itself at a central point, below the core city on the Rhine .

Topography and archaeological findings

The foreland to the east, below the fortification, was fortified by a wall and a moat following some distance away. A house that stood there at the time and belonged to the early St. Aposteln Abbey can be documented for the year 1106. In front of the terrain, which sloped sharply towards the Rhine, was a narrow, elongated Rhine island , separated from an arm of the Rhine that had not been navigable since about the middle of the 2nd century . The period at which the swampy terrain (strip of land and island) in front of the old city changed from a floodplain to a part of the old town that could be used as building land is probably around 200 after the excavations on the occasion of the underground construction in 2000/12.

Excavations in the area of the former Great St. Martin building, which became a monastery church again in 2009 , demonstrated with their archaeological findings from previous Roman buildings there, an early settlement of the area of the Rhine suburb. The originally small and initially poorly endowed church was given extremely generous consideration by Archbishop Bruno's successors . It later became one of the buildings that dominated the district.

Investigations of the Ubier monument found in the Roman port facility in 1965/66 report that oak stakes were driven into the ground. Accordingly, the first drainage was probably carried out using stone and wood material in the form of embankments known as "congries". Over time, these will have led to an elevation of the terrain a few meters southeast of the Roman wall. The elevations must (according to Keussen) have joined a raised wall along the Trankgasse leading to the Rhine, since soil investigations there did not indicate any alluvial land on an island.

history

Historians assume that development was intensified by the 10th century at the latest. As early as 948, the suburb of the Rhine was demarcated from the Severin district by the "Filzengraben" (civitas fossa) leading to the west on its edge . Around this time, a ditch was dug on the north side, parallel to the Roman wall , along the later episcopal garden, after which today's Trankgasse received its first name as Grabengasse. Since the northern side wall of the old cathedral used the Roman wall as a foundation , the moat, beginning at the “ Pfaffenpforte ”, is said to have protected the cathedral. That ditch and led on the right has on the northeast corner of the Domgeländes south Römermauer addition to the Rhine, where its end point with the Frankenturm had occupied a Schreinskarte in which built on the west side of Maximinenstraße road chapel of the hospital (as such inventory of 1183 until 1398) the alms brother of St. Lupus, as "located on the Walle" was described. The Frankenturm, also known as Frankenthoirn, or thorn in the Middle Ages (see Mercator ), stood next to the Trankgassentor . The tower was named after a burgrave "Franco" of the 12th century.

At the southern end of the moat, where the additional protection offered by the Hürther or Duffesbach flowed into the Rhine , stood the "Saphirturm". At the beginning of the 12th century it was owned by the abbey “S. Trond "(probably from the cloth town of Sint-Truiden ) in Flanders , which was also responsible for the defense of the section there, the sub-district" Saphiri ". The tower was later mentioned in connection with the name of the "Hardefust", a Cologne patrician family .

The access from the city center to the growing settlement area was through the Kornpforte at the “Malzbüchel” in the south, on the west side it was the gate on Königstrasse and as a further possibility of access the market gate. The north side of the wall is said not to have had a gate into the forecourt before the collegiate church of St. Maria ad Gradus was built . Only in front of the north and south towers on the Rhine was the ditch to be crossed over bridges.

Work of the city and sovereign rulers

When King Otto named his brother Brun (953–965) , elected archbishop by the high Cologne clergy, a little later as Duke of Lorraine , the city received one of the youngest regents in its history. He spoke on behalf of the king, collected the taxes (court interest) and regulated the city's economic affairs. Bruno built the cathedral school into a leading institution in the empire in order to ensure the training of young people loyal to the empire. The founding of the monastery in Cologne, which, along with St. Pantaleon and St. Andreas, became an essential factor in the development of the Rhine suburb with the establishment of St. Martin, are further evidence of his work . The beginning of Cologne's economic development, starting from the Rheinvorstadt (later also known as the Kaufmannsviertel), is probably due to a privilege that Bruno was given by his royal brother. It was the privilege of market rights , which remained unchallenged in the possession of his successors for a long time, and which was to be of decisive importance for the city.

A list of court interest rates found by the Martinsk monastery, based on a donation from Archbishop Everger († June 11, 999 in Cologne), gave detailed information on the locations of the emerging market district at the time. According to this document, the archbishop left most of the court interest levied in the Rheinvorstadt (the original royal property tax) to the monastery . The list delimited the Hofzinsgebiet west by the Roman wall, east with the streets "Kühgasse" and "Rothenberg", excluded the immunity of the monastery and took the streets "Am Bollwerk" to "Große Neugasse" as the northern limit. The southern border was marked by the houses behind the Rheingasse, where the Martin parish began . Within this outline, the Martinskloster received the court interest and still raised it in the 14th century. Exceptions, the interest of which went to the bishop, were smaller parts of the Rheinvorstadt. It was the lying behind "Rothenberg" and "Kühgasse" smaller markets such as the butter market and areas of fish and Thurn market, and on the west side of the (later) Heumarktes established "Gaddenen" (stalls), which is also on the road "Under hat makers and silk makers" found. Small amounts of interest went on to St. Kunibert , and to St. Aposteln later also to St. Ursula .

The market district

Below, east of Judengasse , behind the Roman wall, which was initially only broken through in a few places, was an increasingly dense development of the district in the southeast of the area, primarily beginning at Rheingasse. The entire area of the Rheinvorstadt soon formed a contiguous market district with a relatively high population density with its small alleys and alleyways, which here and there merged into a widening square. As was often practiced by the market communities in comparable towns in those days, this may have led to the construction of a market church in a new parish , which then chose the patronage of St. Martin . A little later the new quarter was mentioned in a document, it was called mercatus coloniae in 992 .

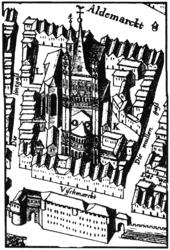

This shows that trade and handicrafts had become very pronounced branches of activity. The turnover of goods in the new quarter and the flow of visitors, including suppliers and customers from outside, must have been enormous, so that the Neumarkt emerged in the period that followed. The entire market area then called “Aldermart” retained the name Altermarkt in all individual descriptions, including in the hay market area, until the 14th century, as evidenced by the topographical evaluations of Keussen.

From the Altermarkt, in the middle of which stood the archbishop's mint (the municipal mint was built next to the Gürzenich in 1474 ), narrow streets with stalls led to another free market area as early as the 11th century. Over time, the accumulation of these buildings divided the entire market into two unequally large sections. The area of these lanes formed the district "Unterlan" which belonged to the immunity area of Archbishop Anno and which was given to the customs officer "Ludolf" as a fief . A permanent residence used the Erbgenossen the district "sub-Lan", they had to 1360 as a courthouse the house of the belt maker in the street "Unter Käster" in lease .

Abbey and parish churches

Not only the increasing population was the decisive reason to build more places of worship. The clergy of the collegiate churches saw their ritual daily routines being impaired by the laity and provided relief. The monastery churches were either subdivided or an existing chapel was expanded. In other cases a new branch church was built for the people and pastoral care was left to a plebanus . In the northwestern foreland, St. Christoph was the parish church belonging to St. Gereon Abbey . In the case of the Church of St. Apostles , which stands in the west behind the fortifications, the same procedure was probably used as in the case of the Kunibert Church and a nave was separated as an area of the community. In comparison to the other suburbs, there was initially only a sparse settlement due to the agricultural areas of the Almende that adjoined the church to the west .

In the case of the St. Georg collegiate church with the St. Jakob parish church and also the St. Severin monastery , which had the St. Maria Magdalenen and St. Jan chapel as parish churches, the same reasons had been the cause. The same was done by the St. Pantaleon Monastery , whose monks owned their own church on their property "in suburbio coloniensis civitatis" , which was later elevated to the parish church of St. Mauritius .

The parish districts bordering the Rhine suburbs were the collegiate church of St. Andreas in the north-west with its parish church of St. Paul and the church of St. Lupus belonging to the St. Kunibert monastery (where only the west aisle was open to the people) . In the south of the market district it was the Marienstift with its parish Peter and Paul, also called "Notburgis", which then merged with the parish of St. Martin.

Most of the later parish churches already existed as such in the 12th century. In the 14th century, their total number within the city walls increased with the elevation of St. Maria im Pesch to 19th parish churches. Most of them had their origins as chapels that were built in connection with monasteries, monasteries or hospitals. In the case of St. Lupus, a former hospital of St. Kunibert is said to have been the origin of the parish church, and in the opposite case, "St. Notburgis “(originally St. Peter and Paul, around 1100) from the status of a parish church to a chapel.

These buildings were mostly created through the favor and financial contributions of the early archbishops of the city of Cologne. In many cases, however, the founders of the Cologne citizenship are also evidenced , primarily from the class of the patrician families .

Parish of St. Martin

Main article: Klein St. Martin

A Martin parish was probably founded in the market district at the beginning of the 12th century at the endeavors of the monks of the Benedictine monastery of St. Martin. Shortly after the introduction of the Cologne shrine tour, it appears in these directories as “s. Martini parvi ”. This united with the parish “St. Peter and Paul ”of the Marienstift . This parish church is mentioned in a shrine file as early as 1140, other documents mentioned St. Martin for the first time between 1172 and 1190. The new parish , with its church built on the old street “Obenmaerspforten” (with its western wall lying on the Roman wall), was located on the Tel in the old Roman city and protruded into the area of the Rheinvorstadt. The later claims of patronage by the Marienstift led to long-term disputes and were possibly the reason why the St. Brigiden chapel, which was built in the northern part of the Rhine suburb in 1172, became a second parish church in the expanded quarter.

In the 13th century, the conflicting parishes apparently came to an agreement. In the Rotulus of St. Maria im Kapitol the location of the church and the cemeteries between the adjacent courtyards were drawn.

The resulting dividing line to the northern part of the original Altermarkt led from the market gate along the booth complex of the Unterlan district to the salt gate. The southern, larger sub-area was named Heumarkt around 1300.

Klein St. Martin, around 20 years after the nave was demolished. Drawing by Wilhelm Wintz , Cologne around 1844

St. Brigids

Main article: St. Brigids

St. Brigiden became the parish church in the northern area of the Rheinvorstadt. Brigida von Kildare is said to have been the patron saint of the new suburb. The church, which probably emerged from a small chapel from the 9th century, was certainly elevated to a parish church for the reasons given above. In 1279, Johann Overstolz made a special donation to the abbot of the St. Martin monastery in Cologne, which was intended for the pastors at St. Brigiden.

Chapels and convents

Chapels

- Chapel of St. Nikolaus and Sergius (around 1148) below the Thurnmarkt at the corner of the Rheingassenpforte, demolished in 1560.

- Chapel of St. Nikolaus in Salzgasse, it was later named St. Michael and was closed in 1589

Convents

- In 1264 a convent (Wiyse?) Took over the hospital of the St. Martin monastery on the Alter Markt

- 1290, Corduanyn Convent. Upper floor of a house "Vor St. Martin", united in 1432 with the lower house of Johann Jude. Johann Jude was mayor of the city with Johann von Lewensteyn in 1425/26

- In 1640 a Servitessen monastery was built on the Filzengraben .

- 1602, Forst Convent (Dahlen and Sylvester) "Auf dem Brand". Founder was Dr. Wilhelm Hackstein

Administration of the Rhine suburb

The area of the Rheinvorstadt, as well as that of other special communities, was often divided into further sub-districts. All were assigned to a parish, the boundaries of which were usually congruent with those of the parish. The parishioners were free to choose a pastor, while in the case of the collegiate churches the right of nomination was incumbent on the canons. Early shrine maps of the Martin parish named several people who were designated as mayors of the district. You can probably be seen as a representative of your community with other colleagues from the other quarters as the forerunners of the Richerzeche . The upper class of the district's citizens met to go to church and after the service went to the nearby “house” to discuss communal matters. The home of the Klein Martin district was on Rheingasse, and the building responsible for St. Brigida was on Alter Markt. The so-called “House of Citizens” on Judengasse, which later became Cologne's town hall , was probably the meeting place for the first Cologne council elected in 1216.

With regard to jurisdiction, the Rhine suburb, like the western suburb behind the fortification behind St. Aposteln, had been subject to the old town courts since earlier times. This was in contrast to the suburbs of Niederich in the north and Oversburg (Airsbach) in the south, whose independent judicial system remained untouched for the time being, even after their incorporation. The early amalgamation of the district upstream of the “Old City” in the east into a uniform legal system was also reflected in the appointment of the lay judges. After evaluating the old files, the Rheinvorstadt never had its own public court; however, the aldermen's colleges were made up of the honorable classes of both parts of the city.

Few of the city's numerous smaller court variants took place on the grounds of the market district. Only the mayor's court on the meat market was held in front of the "Haus zum Sternen" on the Heumarkt, which was bought by the meat merchants in the 15th century as a gaff house. On the chicken market, of which the "Hühnergasse" still reminds us today, was the stock house with a prison and the stocker's apartment at the Marspforte.

In addition to its function as a marketplace, the Alter- and Heumarkt also served as a court and place of execution. Due to the large number of visitors, the pillory, called the Kax in Cologne , and the shed chair were also deliberately placed here in order to achieve the greatest possible scorn and ridicule from the audience for the delinquents. This most important urban kax had been on the old market since 1500 and was renewed in 1570.

Shrine Districts

Data of the source references of the article refer to created shrine maps, shrine districts and sub-districts were established around 1193 according to Keussen.

| S. Martin | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Shrine District | annotation | Shrine District | annotation |

| dom. Henrici Saphiri | (Hardefust) | Kornpforte | (Porta Frumenti) |

| Abbatisse Curia Marie | no | High gate | (Alta Porta) |

| Raitzenhaus | no | dom. Wolberonis | (de Malzbuchel) |

| dom. Alexandri | no | Salzpütz | (Salzgasse) |

| dom. Cunradi de Brule | no | dom. Cristine | no |

| dom. Lewenstein | (Henrici Pinguis scapule) | dom. Anselmi Ustoris | (Sifr. Wlleden) |

| dom. Domine Durechen | no | dom. Wolberonis Vulprumen | no |

| Iron scales | no | dom. Vogelonis filii Johanne | no |

| dom. Evergardi | no | dom. Godefridi Parvi | Parvuse? |

| Rabbit gate | (Engl. Tower) | dom. Henrici Negri | no |

| dom. Marcmanni Wivilruzen | no | dom. Henrici Libratoris | no |

| dom. Hermani de Niderich | no | dom. Philippi Comitis et Blithildis | no |

| dom. Klockringk | no | Ekkehardi de Malzbuchele | (Vrouwenburch) |

| dom. Jordani de Malzbuchele | (Cleve) | dom. Cunradi Panificis | no |

| stupa balnei iuxta p. martinum | no | dom. Erenfridi | no |

| dom. dominorum s. Petri | no | dom. Emundis sub Macellis | no |

| dom. Pelegrini inter Sellatores | no | dom. Gozwini Minnevuz | (Stellerevere) |

| dom. Hermanni filii Ludevici | no | coin | (Moneta) |

| Meat house | no | dom. s. spirit | (Holy Spirit Hospital?) |

| House apostles | (mentioned above in the article) | ||

| S. Brigida | |||

| Shrine District | annotation | Shrine District | annotation |

| floor | (crippus) | Salzgasse Chapel | no |

| Dragon hole | no | dom. Granine | no |

| dom. Bircelin | Mayor Birkelin 1360 | dom. Refridi | no |

| dom. Henrici Corduanari | no | Bread hall | no |

| dom. Windeck | Merchant gaff | dom. Galley | Height fish market |

| Frankenturm | The tower was never privately owned | ||

| Tabular data based on Hermann Keussen | |||

Streets, markets and squares

The two streets that flank it, Filzengraben and Trankgasse , are connected with the development of the Rheinvorstadt . In only three places in the suburb of the Rhine, roads leading to the Rhine were probably roughly preserved as early as Roman times. They are the Mühlen-, Salz- and Rheingasse. A Roman road that used to run down the Bischofsgartengasse through the royal and later the episcopal garden has only survived as a reconstruction of a few meters in length. Also the Mühlengasse (platea molendinorum), the end of which on the Rhine was the original anchorage of the Rheinmühlen , lost its importance after the relocation (mentioned in the sources around 1582) of the Rheinmühlen to the area of the Bayenturm . The Salzgasse, as the former end of a route running from the city center over the Brückenstraße to the former Roman Rhine bridge , had also lost its importance as an important traffic route and has remained a narrow alley to this day. Bechergasse and the street “Unter Käster” connected the western edge of the market quarter, which had been divided into two areas, below Judengasse.

Altermarkt and Heumarkt

At the "Old Market", found at the entrance to Lintgasse (later to Büchel gate in the Wall led Rhein) annually for the season of the harvested pome fruit at the "House for Britzel" an apple sale instead. The sale extended to the St. Brigiden Hospital, which was then sometimes referred to as the "Hospital on the Apple Market".

The major handling of food took place in the southern market area. The center of the hay market had become the center of the food trade for the city and the surrounding area. Here, before a closed hall was built, meat was sold in all its variations on “benches”. To the north of the market stood the cheese and greengrocers as well as the pea and pepper dealers. The latter often had a monopoly with their spices and had become quite wealthy (ironically, they were called "pepper sacks"). On the west side, east of the Marspforte, was the chicken and venison market . The market of the onion traders (the "bacon of the poor people") and the fodder sellers moved towards the center .

The trade in fur and leather goods took place around the mint . To the west of the hay market, it was the furriers who, in their different specializations, sold their goods as colored words, gray words or lambskin dealers. Stalls with extravagant goods such as sable or fox fur were found at the level of the street “Unter Seidmacher” (street on St. Peter's House mentioned in 1163, today Zims).

Towards Martin's gate there was a small hall in which the sole and child shoemakers as well as the saddlers were. Leather cutters or “rim cutters” stood in the street “Unter Käster”. Beginning on the northwest side of the Altermarkt, moving southwards (to behind today's town hall), the "Corduanarii" had found their new place. They made fine goat patent leather and had given up their traditional old seat in the street "Unter Taschemacher". Since the 13th century the bag makers or satchel makers (Peratores), who were also called the “beef skins”, were located there. In earlier times, the area of clothing tailors on the street “Unter Hutmacher” was considered to have a particularly valuable inventory. It was locked and guarded at night. At the end of this street were the stores "Aachen" and "Airsbach" of the woolen weavers of the Greek market and the suburb of Oversburg, whose property was confiscated by the council after the weaving revolt and later became private property.

The salt and coal market took place on the Heumarkt, in front of the entrance to Salzgasse. Further north is the flax market . In the direction of the coin were the stalls of the old buyers (the old smokers, still known today as "old smokers" in Cologne), and behind the coin were the banks of the money changers .

In addition to the St. Brigiden's hospital, there were also the first pharmacies that were important for sick people in the 12th century . They were initially referred to in the shrine files as the “Specionarii” and “Herbatores”, who sold special, dried herbs and spices as medicinal plants . The names later changed to "Kruder" or Herbarius, to which the name "apothecarius" has been added since the 13th century. A house in which "Gris der Kruder" lived was inhabited around 1400 by "Georg von Brugge", known as a pharmacist. According to the sources of this time, all pharmacies in Cologne were apparently on the west side of the Altermarkt and at the Marspforte.

The market district was also the location of various junk stores that had developed from the “stalls” to multi-storey Gadden houses with a wide range of goods on all floors. They were the forerunners of the later department stores.

One of the many municipal facilities for the benefit of trade as well as the city treasury ( Rentkammer ) were the four "cranes", of which the large house crane at Markmannsgassepforte, two more cranes at "Große Neugasse", and the fourth one in Rheingasse were.

Northeast area

The eastern part of the market district began with a narrow area of residential streets, which was followed by the fish market behind St. Martin. This stretched along the banks of the Rhine to Salzgasse, and included parts of the later butter market. After further development of built-up streets, this new residential area east and west of the fish market stalls (parts of what is now Rotenberg and Hafengasse) was called "Small Fish Market".

After Archbishop Konrad granted the Cologne residents stacking rights in 1259 , the city's economic boom intensified. However, after the construction of a fish department store, which was rebuilt at the instigation of the council in 1426 (probably the later stacking house on Mauthgasse), the importance of street sales of these goods declined. The fish market master's office remained on the fish market.

The Buttergasse was further above, parallel to the Alter Markt behind the bread hall. To the east, one block below, was the steel and iron market. This crossed the butter market (which was the extension of the fish market on the other side of Salzgasse). In front of this was the quarter of the forge (inter Ferrarios) further down . In 1483, the council bought the "House of the Jews" on Thurnmarkt and used it from then on as an office to collect the Rhine toll, a right that the city had received in 1475.

Southern area

A type of residential building that was widespread in the Middle Ages still stands on Filzengraben today. It was first mentioned in 1294 as the "Vromoltshaus". Older Cologne residents have known it since 1928 as "Weinhaus Duhr". Werner Overstolz was a lay judge. He is the first to be named Overstolz with the addition "in the Rheingasse" . His house, which is still preserved on this street, was built by the patrician family around 1220 to 1225.

At the Rheingasse gate, several houses were acquired by the council in the 1430s, and after they were demolished, a large building for the grain and flour scale was built there. Among the demolished houses there was one that operated one of the first medieval bathing rooms. The house next to the Rheingasse Gate was built in 1165.

Changes

No information is said to have been found in the sources about further new roads in the market district up to the 14th century. From this time on, the council began at various points to have extensions or breakthroughs made in the interests of traffic . This happened in 1372 with the street "Unter Seidmacher". If necessary, these projects were carried out by buying and then laying down houses (for example at Rheingassentor 1438 and at Heumarkt 1439). Since the construction of the Gürzenich , Bolzengasse has been expanded by continuously demolishing houses (1448, 1475, 1478 and 1481). In the 16th century this road to the Heumarkt broke through. A simultaneous breakthrough turned the cul-de-sac leading to the “Sassenhof” (later the site of the wholesale market hall, now the Hotel Maritim) into a traffic route to the east. A better access to the market quarter was created in 1545 by the demolition of the Marspforte. In 1547 the council removed the "Gaddenen" that were in the middle of the street "Unter Käster". In 1569 the chapel in the Rheingasse and in 1589/90 the one in the Salzgasse were laid down on the grounds of “bringing light and air into built-up corners”.

From the suburb to the old town

Much of the old substance in the medieval Rhine suburb was initially lost not through wars, but through devastating fires (this is also said to be the origin of the street name "Auf dem Brand"). From the modern era , when half-timbered and wooden buildings were slowly being replaced by massive stone buildings in the inner city , many multi-storey, magnificent town houses were built , the builders of which in the Rhine suburbs mostly belonged to the wealthy class of merchants. So at the beginning of the Hanse Kontore, branches of the city association and large warehouses were built.

Losses of old buildings, which the market district also suffered in the French era , mostly concerned monastic facilities. The historical buildings that had been laid down in the early days of the Prussian era were also finally lost. It was not until the Second World War that the "historic Rhine suburb" was almost completely destroyed.

A number of old buildings have been preserved or, like the churches in the district, have been lovingly restored, but at great expense. Names like the district “Unterlan” or the district “Auf dem Himmelreich”, once the name of a gaff, are hardly known today. The Straßburgergasse, a street that existed until the 20th century and was mentioned in the shrine of the “Saphiri” subdistrict, is no longer there. The term “Unterlan”, Binger- and Weite Gasse disappeared. The Botengasse became Budengasse and can only be guessed at in its original meaning. Nevertheless, many of the old names have been retained through the commitment of Ferdinand Franz Wallraf .

literature

- Paul Clemen (ed.): The art monuments of the city of Cologne. Supplementary volume: Ludwig Antz, Heinrich Neu, Hans Vogts : The former churches, monasteries, hospitals and school buildings of the city of Cologne. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1937 ( Die Kunstdenkmäler der Rheinprovinz 6, 7) (Reprint. Ibid 1980, ISBN 3-590-32107-5 ).

- Toni Diederich : From the beginnings in Roman times to the end of the High Middle Ages. Echo-Buchverlag, Kehl am Rhein 1994, ISBN 3-927095-17-6 ( The Archdiocese of Cologne. Issue 1).

- Carl Dietmar: The Chronicle of Cologne. Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger et al., Cologne 1991, ISBN 3-611-00193-7 .

- Klaus Dreesmann: Constitution and proceedings of the Cologne council courts. Dissertation in the Law Faculty of the University of Cologne, 1959.

- Hubert Graven: The emblems of the old Cologne University in connection with intellectual life and art. In: Festschrift commemorating the founding of the old University of Cologne in 1388. Schroeder, Cologne 1938, 384–459.

- Heinz Heineberg : urban geography. 2nd revised edition. Schöningh, Paderborn 1989, ISBN 3-506-21150-1 , p. 63 ( floor plan general geography. Vol. 10).

- Hermann Keussen : Topography of the city of Cologne in the Middle Ages. 2 volumes. Hanstein, Cologne 1910 ( price publications of the Mevissen Foundation 2, ZDB -ID 520567-0 ), (reprinting taking into account the "Revised special print", Bonn, 1918. Droste, Düsseldorf 1986, ISBN 3-7700-7560-9 ( Vol. 1), ISBN 3-7700-7561-7 (Vol. 2)).

- Gerd Schwerhoff : Cologne in cross-examination. Crime, Domination, and Society in an Early Modern City. Bouvier, Bonn et al. 1991, ISBN 3-416-02332-3 (also: Bielefeld, Univ., Diss., 1989).

- Gerta Wolff: The Roman-Germanic Cologne. Guide to the museum and city. 5th expanded and completely revised edition. JP Bachem, Cologne 2000, ISBN 3-7616-1370-9 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Gerta Wolff: The Roman-Germanic Cologne. 5th edition, pp. 242-245, JP Bachem.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, p. 35: “ domus in Veteri foro cum furnario et umbraculo, quod vulgo halla dicitur, ad vallum sito ”

- ↑ Marcus Trier on the end of the archaeological excavations around the Cologne subway construction, Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger April 12, 2012, p. 25 ( ksta.de ).

- ↑ Bulte, m. tuber, acervus, congeries, pile, hill. In: Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm (Hrsg.): German dictionary . tape 2 : Beer murderer – D - (II). S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1860, Sp. 514 ( woerterbuchnetz.de ).

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, p. 35, reference to: Schwöebel: Bonner Jahrbuch. 82, 25 p. 17.

- ↑ Ludwig Arentz, H. Neu, Hans Vogts: Paul Clemen (ed.): The art monuments of the city of Cologne. P. 65: "The establishment of the 'scribes' (popular parlance) venerated St. Kunibert as a founder from time immemorial."

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume II, 160b 5: 1163/8 “ domus in Vallo iuxta s. Lupum ”.

- ↑ Adam Wrede, Volume I, pp. 245-246.

- ^ Carl Dietmar: The Chronicle of Cologne. SS 53.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, p. 37, reference to: Beyer, Mittelrhein. Document book, I n.263.l, Bonner Jahrbuch 82, 25 p. 17.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, p. 37.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, p. 37 “ domicilia in Foro, que dicunter lan ”.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, p. 145.

- ↑ Ludwig Arentz, H. Neu, Hans Vogts: Paul Clemen (ed.): The art monuments of the city of Cologne. P. 77.

- ^ Paul Clemen: Die Kunstdenkmäler der Rheinprovinz, on behalf of the Provincial Association. Cologne B. II 1, p. 31.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, pp. 137, 138.

- ↑ Schwerhoff: Cologne in cross-examination. Crime, Domination, and Society in an Early Modern City. P. 140 f.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Extract from the map sheet 6.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, p. 158 f.

- ↑ a b Keussen: Topography of the city of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, pp. 137, 159.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, pp. 120 f., 159.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, p. 141, with reference to: Knipping p. 160.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, pp. 137, 158.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume II, p. 12, column 2.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, p. 134.

- ^ Hermann Keussen: Topography of the City of Cologne in the Middle Ages. Volume I, p. 168.