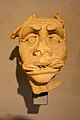

Grin head

So-called Grinköpfe , also called Anno heads are grotesque stone grotesque masks as decoration on many older Cologne attached houses.

From the decorative mask to the grin head

Early Roman pottery has been documented and documented for some Cologne districts through excavations commissioned by the “Office for Soil and Monument Preservation Cologne”. These craft businesses belonged to the "Oppidum Ubiorum", a predecessor settlement of the Roman CCAA .

As in previous years, a major construction project in 1997 made it possible to gain important insights into the pottery production of this time through archaeological investigations. Nineteen Roman pottery kilns were uncovered on an area of around 100 m² on Lungengasse, south of Neumarkt , where Roman ceramics had already been found in 1956 near Thieboldsgasse . The factories, which were formerly a larger pottery district, produced various kinds of ceramics in so-called “standing ovens”, the combustion chambers of which were between 1.8 and 2.6 m in size, to meet the everyday needs of the urban population and the demands of the surrounding area covered. Was burned Weißtonware but also so-called Terra Nigra .

While the finds from earlier excavations in the city area were not very informative, numerous false fires were recovered during the 1997 excavation, which provided the experts with information on the extent and type of production.

Clay masks from Roman times

Many sites along the Rhine valley testify to pottery that can be assigned to the Roman period. A concentration of such craft businesses, which had specialized in the production of clay masks, was found in the Cologne city area, where more than 200 fragments of these terracotta masks were recovered. They are among the rather rare finds from Cologne's Roman past, as their fragility, in contrast to the solid materials used in other objects of Roman origin, outlived the centuries less often.

The masks , provided with openings for eyes, mouth and nose, were life-size. As a rule, they depicted ugly disfigured, terrifying faces of bald men who were depicted with excessively long or wide noses and dagger-like teeth in their open mouths. On the other hand, they also produced masks of beautiful female heads with elaborate hairstyles , whose hair was decorated and held by pieces of jewelry.

The masks were made from plaster of paris using hollow molds into which the moist clay was pressed. Once this was dry, the mask was removed from the mold, given a fine treatment and painting, and then baked. Since numerous impressions could be made from one model, regular series production was the result .

The meaning of the masks remained unclear for a long time, as the context of their place of discovery provided no explanation. The latest excavations in the Alteburg naval fort in Cologne certainly prove that they were used as decoration for the building and garden architecture. The masks were found on both public and private buildings, occasionally also, possibly as a votive offering , in sanctuaries . Assumptions that such masks could have been used for representational purposes in ancient theater are considered improbable. They are too heavy, have sharp ridges on the back and have no type of reference to ancient theater designs in tragedies or comedies .

The economic reason for the productions, however, is unmistakable. The masks were only made in a few settlements of this epoch and could easily be assigned to a certain location based on a few specific manufacturing characteristics. Cologne took on a leading role in this area, probably also because the city offered ideal conditions for this craft. Cologne had the necessary raw materials such as water, clay and wood from the forests that were still in existence, but also the sales market of a large city on the Rhine that was linked to well-developed highways . In addition, there were craftsmen who had been in the pottery for generations and who had refined the method of making their goods.

Between 90 and 200 AD , the potters produced pottery of all kinds in the area of today's Rudolfplatz, as well as crockery, oil lamps and small figures and masks in large numbers. Due to the flourishing export across the Rhine, the masks reached many European countries. Fragments of Cologne masks were found in Switzerland , the Netherlands , Belgium and even England . So far there has been no evidence of a possible continuation of mask production in the post-Roman period. It was not until the 11th century that a legend suggests that knowledge of such sculptures existed.

Further development

The masks, coveted in Roman times, were found in the stone sculptures of the Middle Ages. They corresponded to the type of the former terracottas, which, now made of tuff or sandstone , were initially attached to house facades for centuries for a specific purpose.

Interpretations of the name

The name Grinkopf is found for the first time in 1616 in the guild records . The root of the word is derived from 'grin', 'grin', 'laughing out loud'. It is not known whether the lion heads, which are also used as facade decorations, are related to the legendary lion fight of the legendary Cologne Mayor Hermann Gryn (in the sources also Grin), but it is known that grin heads were also attached to the town hall buildings . A reference to the Cologne patrician family of the "Grin" has not been proven.

Late Middle Ages

The architecture of Gürzenich , created in 1441, found many imitations in the private buildings that followed. The house fronts, which had previously been designed for the most part, were given crenellated crowns , corner guards and other decorations, which were joined by interior and exterior picture decorations.

- Decorative forms of an interior

Just like the Gürzenich, which was decorated with rich facade decorations in the prewar period, the interior of the house on Marienplatz that was acquired in the middle of the 15th century by the later mayor family Hardenrath was adorned with demon-like heads. These were preserved as wall and vault decorations until 1970.

Purpose and trimmings

The use of the sculptures, later referred to as grin heads, was thought to be both decorative and functional. According to Adam Wrede , for whom these heads are of course called "Jrinkoepp" (still 1825/40) in Cologne dialect , there were different versions. On the one hand, there was the grimace head carved in stone in the top of the gable of the merchant's houses, which served as a crane to pull bales, boxes, and sacks onto the warehouse, and on the other hand, it was usually mounted above the cellar entrance or a cellar opening on the plinth front. There lions or grin heads were placed above the openings in the outer wall in order to temporarily lock one or two logs (so-called scrap trees ) in the wide, open, “grinning” mouths provided with pointed teeth , as long as they were used to attach a winch were used to lower heavy loads, such as wine barrels or other heavy items (which were jokingly called artillery pieces) into the cellar.

- Sculptures of the heads preserved in today's cityscape

Grinkopf at a house on Appellhofplatz

The later changes in house construction made the grin heads a traditional, pure decoration of house facades. There was a move towards building double entrances, a wider one for goods and cellar transport and a narrower one for access to the living area.

Present stock

Only a few of the heads that were later attached to the houses traditionally and for decoration (mostly in the old town) are left due to the effects of the Second World War . After all, during the reconstruction (as in earlier times when old buildings were demolished), some heads were attached to the new building as the only remnants of an old house. It is also mostly not possible for outsiders to see whether the sculptures that still exist are originals or replicas and their original location. Most of the time, copies were made to protect them from weathering, and the original pieces were often installed inside the building or were taken to the museum.

literature

- Hans Vogts: The Cologne house until the middle of the 19th century . Volume 1. Verlag Gesellschaft für Buchdruckerei, Neuss 1966, Rheinischer Verein für Denkmalpflege und Heimatschutz e. V. Cologne; Pp. 149-152.

- Adam Wrede : New Cologne vocabulary . Volume 1. Greven-Verlag, Cologne 1956–1958. P. 314. ISBN 3-7743-0155-7 .

- Bernd Imgrund: 111 places in Cologne that you have to see . Volume 2. Emons Verlag, Cologne 2009, p. 80f. ISBN 978-3-89705-695-4 .

- Heinz Günter Horn, Hansgerd Hellenkemper (eds.), Maureen Caroll, Hannelore Rose, In: Findort North Rhine-Westphalia Millions of years of history : Writings on the preservation of monuments in North Rhine-Westphalia, Volume 5, Cologne 2000 ISBN 3-8053-2698-X .

- Hans Vogts , Fritz Witte: Die Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Köln , on behalf of the Provincial Association of the Rhine Province and the City of Cologne, published by Paul Clemen , Vol. 7, Section IV: The profane monuments of the city of Cologne , Düsseldorf 1930. Verlag L. Schwann, Dusseldorf. Reprint Pedagogischer Verlag Schwann, 1980. ISBN 3-590-32102-4 .

- Carl Dietmar: Die Chronik Kölns , Chronik Verlag, Dortmund 1991, ISBN 3-611-00193-7 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Maureen Caroll: early Roman pottery in Cologne . In: Heinz Günter Horn, Hansgerd Hellenkemper (Hrsg.): Location North Rhine-Westphalia, millions of years of history . P. 329

- ↑ A photograph enclosed by the author in this essay shows fragments of the terracottas, but is not in the public domain for reasons of copyright

- ↑ Hannelore Rosel: in Heinz Günter Horn, Hansgerd Hellenkemper (Hrsg.), In: Findort Nordrhein-Westfalen Million Years of History , New Findings on the Roman Terracotta Masks, p. 331 f

- ↑ a b Vogts, Witte: Die Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Köln , on behalf of the Provincial Association of the Rhine Province and the City of Cologne. (Ed.) Paul Clemen, vol. 7, section IV: The profane monuments of the city of Cologne , p. 400

- ↑ August Sander: Cologne as it was . Edited by Rolf Sachse, edited by Werner Schäfke , Cologne 1988

- ^ Hermann Keussen , Volume I, plate district S. Martin, and p. 51, Col. 2

- ^ Adam Wrede, Volume I, p. 314