Kölsch (language)

| Kölsch | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Cologne ( Germany ) | |

| speaker | 250,000 to 750,000 | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | - | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

gem (Germanic languages) |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

ksh |

|

Kölsch ( IPA : [ kʰœlʃ ], kölsche pronunciation: [ kœɫːɕ ] ; also: Kölnisch ) is the largest variant of Ripuarian and Central Ripuarian within Middle Franconian in terms of number of speakers . It is spoken in Cologne and in variants in the surrounding area. Instead of the original Cologne dialect, a toned down Rhenish regiolect is often used as the colloquial language (but often with a typical Cologne tone , which outsiders sometimes mistake for "Kölsch").

Ripuarian, together with the Moselle-Franconian dialects and the Luxembourg language ( Letzebuergesch ), is part of Middle Franconian, which with the Benrath line (maache-maake line) is differentiated from the Lower Franconian Platt near Düsseldorf . The from the Rhineland Regional Council published (LVR) Rheinische subjects shows more dialect boundaries ( isoglosses on): as the north running on the Lower Rhine uerdingen line (ech-ick-line) which the Südniederfränkische (also Ostlimburgisch called) from the northern Lower Franconian with the variants Kleverländisch and East Bergish demarcates ; further east of the Rhine the border to the Westphalian dialects called the unit plural line ; to the south, following the course of the Rhine, there are further dialect borders.

There are lexical references to modern German and the other Ripuarian languages as well as to Middle High German , Low German , Dutch , English and French , phonetic references to Limburg , Middle High German, French and Walloon , grammatical references to English, Palatinate and Dutch. Although Kölsch allows for variations in the lexicon in individual cases and the pronunciation also varies slightly regionally and according to social class, most of its aspects are precisely defined.

Language codes according to ISO 639 are:

- ksh for ISO 639-3 and

- gem for ISO 639-2, since Kölsch is listed there under the collective identifier for "other Germanic languages ".

- the 14th edition of the Ethnologue was: KOR,

- since the 15th edition it is: ksh.

The latter was adopted as ISO 639-3 in 2007 .

Origin and creation of Kölschen

From the 3rd century onwards, Franconian tribes penetrated from the right bank of the Rhine to the left bank of the Rhine and expanded into the areas partially populated by Romans and Gallo- Romans . The Salfranken expanded through the present-day Netherlands and Belgium to present-day France. The Rhine Franconians spread along the Rhine to the south and into the Moselle region and made Cologne their royal seat (where they were later called Ripuarier ). In the 6th century, the Merovingian king Clovis I united the two Franconian peoples into one people and founded the first Franconian Empire . Under the Franconian ruler Dagobert I , a compulsory collection of laws was published in Cologne in the 7th century, known as Lex Ripuaria .

After five centuries of Roman city history, the vernacular of which there are no records, Cologne came under Frankish rule in the middle of the 5th century. The local Latin-speaking population ( Gallo -Romans and the Romanized tribe of the Ubier ) came under Frankish suzerainty and was eventually assimilated . Gradually, the official Latin was replaced by the Germanic Old Franconian , but even here detailed evidence of the language level is extremely rare. What is certain is that by the eighth century the so-called second German sound shift , coming from the south, spread out in a weakening manner up to about a day's journey north and west of Cologne.

It was not until the Ottonian era that Cologne began to develop its own urban language as the language of official and ecclesiastical documents, and later also of high-ranking citizens, which can be documented from the 12th and 13th centuries. From the first half of the 16th century this is also documented in literary writings, after Heinrich Quentell or Bartholomäus von Unckell had already printed the so-called “Lower Rhine” Cologne Bible in 1478/79 .

The basis of the language is the former Old and Middle High German and Low Franconian in the special Ripuarian expression of the extensive surrounding area, which today roughly corresponds to the administrative district of Cologne . In the Middle Ages, the emerging Old Cologne niche was so strongly influenced from the south by the emerging Middle High German that it is now one of the northernmost variants of the High German dialects. But it remained in constant contact with the Lower Franconian in the north and west, which also includes the developing Dutch . It has remained that way to this day, only the influence of the Hanseatic League with its Low German business language has disappeared with its decline.

At the end of the 16th century, Cologne's own written language was given up in Lower Franconia and converted to the developing New High German written language; Since then, the spoken and written language have gone their own way. It is therefore natural to speak of a separate Cologne dialect from the early 17th century. Apart from a few individual cases, however, this can only be followed in literary terms at the end of the 18th century.

Since the beginning of the 19th century, Kölsch has been used more and more extensively in poetry and prose, and numerous publications on and about Kölsch enrich the image of this language to this day. This also shows the changes in vocabulary, speech and usage that have taken place since then and which testify to the liveliness of the language.

Position of Kölschen in society

General

In contrast to other dialects in the German-speaking area, Kölsch was never seriously threatened with extinction in the past; however, in the middle of the 19th century, Kölsch was stamped as the language of the workers. After the Second World War, however, they no longer confessed to Kölsch to counter the prejudice; Kölsche was then spoken more by the bourgeoisie in order to convey a feeling of home after the war. However, in the 1970s it was frowned upon as the language of workers and criminals, which led to the fact that many families no longer spoke Kölsch. With bands and music groups like the Bläck Fööss , Kölsche recovered from these prejudices. Similar to Berlin , Kölsch has firmly established itself as a city dialect and is still dominated by a large number of Cologne residents, even though in the last few decades there has been a shift towards High German and only a few young people are learning to speak Kölsch. “Deep Kölsch”, the unadulterated dialect , is spoken today by relatively few, mostly older Cologne residents, who were able to develop their vocabulary in their childhood without the influence of modern communication media.

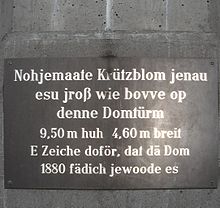

The commitment with which the Cologne dialect is cultivated by its speakers and constantly recalled can be illustrated by many examples: Even headlines in tabloids , obituaries , advertising slogans and public inscriptions are often in Kölsch. There is also a lively tradition , especially the Cologne Carnival . With theaters (Volkstheater Millowitsch , Hänneschen-Theater , Kumede ), a dense scene of carnival and other dialect music groups (up to so-called Kölschrock ) and a large number of Cologne folk poets, Cologne has a rich, Cologne-influenced cultural offer.

Among other things, this was taken as an opportunity to create the Akademie för uns kölsche Sproch, an institution supported by a foundation that aims to preserve and maintain Kölsch beer. Among other things, attempts are made there to codify Cologne's vocabulary and grammar , and rules for the written language are proposed. There are a number of dictionaries, but none have a regular orthography. In the Cologne Dictionary , published by the Academy, suggestions for writing rules are given and explained. For every word entry there is a pronunciation according to a slightly modified IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet). The linguistic approach, however, is repeatedly thwarted by the fact that the cultural workers in particular write Kölsch on their own initiative, namely write it as they think it corresponds to the pronunciation. Since there are often theoretically several possibilities (so eets / ehts / eez / ehz, ) and non-native speakers often try their hand at Kölschen (compare hide instead of vereche, ), Butz (instead of Botz, ) ), because the closed, but at the same time short o is indistinguishable from the u, this leads to a large variety of spellings.

Cologne literature and music

As an example of Cologne local poets , many Cologne residents will first cite Willi Ostermann , who left a rich dialectic legacy to his hometown with odes , songs and poems . The Millowitsch family , who ran a puppet theater in the 19th century, from which today's Volksbühne developed, are similarly known and popular . The current director Peter Millowitsch , like his aunt Lucy Millowitsch in the past, writes his own dialect and regional language plays. The Hänneschen Theater , a puppet theater that only performs pieces in deep Kölsch, has also existed since 1802 , as does the Kumede , a popular amateur theater.

Well-known dialect authors such as Peter Fröhlich , Matthias Joseph de Noël , Wilhelm Koch , Hanns Georg Braun, Peter Berchem , Lis Böhle , Goswin Peter Gath , Wilhelm Schneider-Clauß , Peter Kintgen , Johannes Theodor Kuhlemann , Anton Stille, Suitbert Heimbach , Wilhelm Räderscheidt , Max Meurer, Laurenz Kiesgen , and Volker Gröbe promoted Kölsch as a written language from an early age .

Due to the carnival, the songs in the Cologne area developed independently; some bands that became famous for their carnival, among other things, are the Bläck Fööss , Brings , Höhner , Räuber , Paveier and Kasalla . Songs like Viva Colonia by the Höhner are also very popular outside of Cologne. In addition, the held on Kölsch, carnival has Büttenrede established itself as a populist art form. The songs of the band BAP are not related to the carnival, but also largely in Kölsch .

Cologne insiders

As a supraregional trading center between the Middle Rhine and Lower Rhine with stacking rights , Cologne was always in contact with any traveling people. Similar to the Rotwelschen , there was always a need for communication among Cologne traders, innkeepers and citizens that was not necessarily completely understood by everyone. This was also helpful under French and Prussian rule .

Regional importance

The complicated variety of dialect variants in the Rhenish subject ensures a considerable number of different local languages. Their aging speakers, who grew up with the dialect of their village as their colloquial language, are becoming fewer, the middle-aged residents have often moved here and have brought their dialect with them, be it East Prussian or that of the neighboring town, or Kölsch. Since the 1960s at the latest, a permanent urban exodus can be observed far into the surrounding area, in which not necessarily many of the particularly primitive Kölsch, but German speakers who are influenced by the Cologne language or regional ects, carry on parts of the Kölsch and thus press the local dialects.

Linguistic features

Phonetics and Phonology

To clarify the pronunciation, the transliteration should be used here, which uses the letters of the alphabet. Some regularities in comparison to today's standard German can be roughly specified for Kölsch:

Vowels

| Front | Centralized in front | Central | Centralized in the back | Back | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |||||||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Closed | iː | yː | uː | |||||||||||||||||

| Almost closed | ɪ | ʏ | ʊ | |||||||||||||||||

| Half closed | e | eː | O | O | O | O | ||||||||||||||

| medium | ə | |||||||||||||||||||

| Half open | ɛ | ɛː | œ | œː | ɔ | ɔː | ||||||||||||||

| Almost open | ɐ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Open | ɑ | ɑː | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cologne | * Old Cologne | * Old Franconian | * Original Germanic | Old High German | Middle High German | New High German |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A ss [ʔɑs] | a st [ʔɑstʰ] | a st [ʔɑst] | a staz [ˈɑs.tɑz] | a st [ʔɑs̠t] | a st [ʔäɕtʰ] | A st [ʔästʰ] |

| Aa sch [ʔɑːɕ] | ar s [ʔɑrɕ] | ar s [ʔɑrs] | ar saz [ˈɑr.sɑz] | ar s [ʔɑrs̠] | ar s [ʔärɕ] | Ar sch [ʔäɐ̯ʃʷ] |

| E ngk [ʔɛŋkʰ] | e nde [ʔɛn.də] | e ndi [ʔen.di] | a ndijaz [ˈɑn.di.jaz] | e ndi [ʔen.di] | e nde [ʔɛn.də] | E nde [ʔɛn.də] |

| Ää d [ʔɛːtʰ] | er de [ʔɛr.də] | he đa [ʔer.ðɑ] | he þō [ˈer.θɔː] | he there [ʔer.dɑ] | er de [ʔɛr.də] | He de [ʔɛɐ̯.də] |

| D e stel [ˈdes.tʰəl] | d i stel [ˈdɪɕ.tʰəl] | đ i style [ˈðis.til] | þ i stilaz [ˈθis.ti.lɑz] | d i style [ˈdis̠.til] | d i stel [ˈdɪɕ.tʰəl] | D i stel [ˈdɪs.tʰəl] |

| L ee d [leːtʰ] | l ie t [liə̯tʰ] | l io þ [lio̯θ] | l eu þą [ˈleu̯.θɑ̃] | l io t [lio̯t] | l ie t [liə̯tʰ] | L ie d [liːtʰ] |

| Rh i ng [ʁɪŋ] | R ī n [riːn] | R ī n [riːn] | R ī naz [ˈriː.nɑz] | R ī n [riːn] | R ī n [riːn] | Rh ei n [ʁäɪ̯n] |

| W ie v [viːf] | w ī f [viːf] | w ī f [wiːf] | w ī bą [ˈwiː.βɑ̃] | w ī p [wiːp] | w ī p [viːpʰ] | W ei b [väɪ̯pʰ] |

| D o men [dɔ.nɐ] | d o ner [dɔ.nər] | đ o nar [ðo.nɑr] | þ u nraz [ˈθun.rɑz] | d o nar [ˈdo.nɑr] | d o ner [ˈdɔ.nər] | D o men [dɔ.nɐ] |

| O vend [ˈʔɔː.vəntʰ] | ā vent [ˈʔɑː.vəntʰ] | ā vanþ [ˈʔɑː.vɑnθ] | ē banþs [ˈɛː.βɑnθs] | ā bant [ˈʔɑː.bɑnt] | ā bent [ˈʔäː.bəntʰ] | A bend [ˈʔäː.bəntʰ] |

| H ö ll [Hoel] | h e lle [ˈhɛl.lə] | h e llja [ˈhel.lʲɑ] | h a ljō [ˈxɑl.jɔː] | h e lla [ˈhel.lɑ] | h e lle [ˈhɛl.lə] | H ö lle [hœ.lə] |

| R ö dsel [ˈʁœː.ʦəɫ] | r æ tsel [ˈrɛː.ʦəl] | r ā disli [ˈrɑː.dis.li] | r ē disliją [ˈrɛː.ðis.li.jɑ̃] | r ā tisli [ˈrɑː.tis̠.li] | r æ tsel [ˈrɛː.ʦəl] | R ä tsel [ʁɛː.ʦəl] |

| L o ss [ɫos] | l u st [lʊɕtʰ] | l u st [lust] | l u stuz [ˈlus.tuz] | l u st [lus̠t] | l u st [lʊɕtʰ] | L u st [lʊstʰ] |

| B o ch [boːχ] | b uo ch [buə̯x] | b uo k [buo̯k] | b ō ks [bɔːks] | b uo ch [buo̯χ] | b uo ch [buə̯x] | B u ch [buːχ] |

| B ö sch [bøɕ] | b u sch [bʊɕ] | b u sk [busk] | b u skaz [bus.kɑz] | b u sk [bus̠k] | b u sch [bʊʃʷ] | B u sch [bʊʃʷ] |

| Z ö gel [ˈʦøː.jəɫ] | z ü jel [ˈʦʏ.jəl] | t u gil [ˈtu.ɣil] | t u gilaz [ˈtu.ɣi.lɑz] | z u gil [ˈʦu.gil] | z above sea level [ʦʏ.gəl] | Z ü gel [ʦyː.gəl] |

| H u ngk [hʊŋkʰ] | h u nt [hʊntʰ] | h u nt [hunt] | h u ndaz [ˈxun.dɑz] | h u nt [hunt] | h u nt [hʊntʰ] | H u nd [hʊntʰ] |

| Br u d [bʁuːtʰ] | br ō t [broːtʰ] | br ō t [broːt] | br au dą [ˈbrɑu̯.ðɑ̃] | br ō t [broːt] | br ō t [broːtʰ] | Br o t [bʁoːtʰ] |

| L ü ck [ˈlʏkʰ] | l iu de [ˈlyːdə] | l iu di [ˈliu̯.di] | l iu dīz [ˈliu̯.ðiːz] | l iu ti [ˈliu̯.ti] | l iu te [ˈlyː.tʰə] | L eu te [ˈlɔʏ̯.tʰə] |

| Üh m [ʔyːm] | ō m [ʔoːm] | ō heim [ˈoː.hei̯m] | aw ahaimaz [ˈɑ.wɑ.xɑi̯.mɑz] | ō heim [ˈoː.hei̯m] | ō home [ˈʔoː.hɛɪ̯m] | O home [ˈʔoː.häɪ̯m] |

In contrast to most of the Central German and East Upper German variants, Kölsche has the New High German diphthonging of the Middle High German long vowels ī , ū , iu [yː] (in words like mhd. Wīn [viːn]> nhd. Wein [väɪ̯n], cf. ksh. Wing [vɪŋˑ], mhd. hūs [huːs]> nhd. house [häʊ̯s], cf. ksh. Huus [huːs], mhd. hiute [hyːtʰə]> nhd. today [hɔʏ̯tʰə], cf. ksh. hügg [hʏkʰ]) not completed. Diphthongs “ei”, “au”, “eu” etc. therefore remain either contracted to a single vowel in Kölsch (examples: mhd. Īs [ʔiːs]> Eis [ʔäɪ̯s], cf. ksh. Ies [iːs], mhd. Ūs [ʔuːs]> nhd. From [ʔäʊ̯s], see ksh us [ʔʊs], mhd. Liute [lyːtʰə]> nhd. People [ˈlɔʏ̯tʰə], see. Ksh . Lück [lʏkʰ], mhd. Vīren > nhd. Celebrate [ ˈFäɪ̯ɐn], cf. ksh. Fiere [ˈfiˑʁə].), “-Ein” (<mhd. “-Īn”) often appears in Kölschen as “-ing” (for example: Rhein [ʁäɪ̯n] and Rhing [ʁɪŋˑ], mein [mäɪ̯n] and ming [mɪŋˑ]), or they are spoken differently: the building [bäʊ̯] and dä building [bɔʊ̯ː], dream and dream [ˈdʁœʏmə]. In very rare cases, diphthongs are pronounced - usually in the final - as in High German: Schabau [ɕäˈbäʊ̯].

On the other hand, there is also diphthonging in Kölschen, which means that a single vowel of the German word appears as a diphthong in Kölschen, e.g. B. nhd. Rest [ˈʁuːə] to ksh. Rauh [ʁɔʊ̯ˑ], nhd. Snow [ʃneː] to ksh. Schnei [ɕnɛɪˑ], nhd. Sauce / Sauce [ˈzoːsə] to ksh. Zauss [ʦaʊ̯s], NHG. Flutes [fløː.tʰən] to ksh. fleute [ˈflœʏ̯.tʰə], nhd. disk [ˈʃʷäɪ̯.bə] to ksh. Schiev [ɕiːf], NHG. Squirt [ʃʷpʁɪ.ʦən] to ksh. spreuze [ˈɕpʁœʏ̯.ʦə], nhd. spit [ˈʃʷpʊ.kʰə] to ksh. Späu [ɕpœʏ̯]. Usually these are Central and Lower Franconian vowel combinations typical of Kölsch (cf. left fluiten ) or loan words (cf. French sauce ).

The "sound coloring" compared to standard German sometimes changes, for example from u [ʊ] to the closed, short o [o] (Lust> Loss), from a [ɑː] to the open, long o [ɔː] (sleep> sleep), or from the short, open e [ɛ] to the long, open ä [ɛː] (path> Wäg). As a rule of thumb, these are the same or very similar in most other Ripuarian languages .

The vowels o , ö , e have a special position. While there are only two variants of pronouncing an o in High and Low German , namely half-closed and long [oː] (boat, gentle) or half-open and short [ɔ] (summer, still), there are also the other two in Kölschen Combinations: half-closed and short [o] (Botz = pants, Fott = buttocks) and open and long [ɔː] (Zoot = variety, Krom = stuff). Likewise with ö , the four variants: long and half-closed [øː] (Bötche = Bötche), long and half-open [œː] (Wöbsche = vest, doublet), short and closed [ø] (kötte = begging, öm = um), short and frank [œ] (Kött = tailcoat). Even with e there beside the long German version [E] (take Kess = box nemme =) (broom, path) the short half-closed alternative [e]; in addition the Schwa [ə], which occurs in Dutch and High German , but occasionally disappears or appears in Kölsch in favor of the sentence melody and accentuation (Black (re) m = swarm, (e) su = so, (e) ne = a) The short , half-open [ɛ], e , of German (Fett, Pelle) does not differ in terms of sound in Kölschen from ä , which is rarely taken into account in the spelling.

A noticeable part of the sound coloration deviating from today's High German is more or less pronounced in Kölsch with an extensive linguistic region along the Rhine. For example, one observes high German "wash", "washing machine" to kölsch "laundry", "washing machine", everywhere between about Kaiserslautern ( Palatinate ) and the lower Rhine ( Rhine-Maasland )

The length of the vowels varies. Some short vowels from German are long in Kölschen: make ([mäχn̩]) to maache ([mäːχə]), roof ([däχ]) to daach ([däːχ]). Conversely, some of the long German vowels are short in Kölschen: give ([geːbm̩]) zu gevve ([jɛvə]), tones to tones. Sometimes the length is the same: Apple ([äp͡fl̩]) to Appel ([äpʰəɫ]), Pfahl ([pʰɔːɫ]) to Pohl. It should be noted that, like other Ripuarian languages, Kölsch has three vowel lengths in addition to two rare special cases, in contrast to only two in German. In the sentence “En Wesp mäht sich op der Wäg” (a wasp is on its way) the duration of the following “ä” sound is roughly doubled compared to the preceding “ä”.

In contrast to most of the vowel colors, the Ripuarian languages differ more from each other in terms of vowel lengths, especially the western ones, which are more influenced by Lower Franconia , differ significantly from Kölsch. Further vowel properties are described below towards the end of the section on speech flow .

Consonants

| rule | Cologne | * Original Germanic | New High German | rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Franconian [ p ]> dialect Franconian [ f (ː) ] | dee f [deːf] | deu p az [deuːpɑːz] | tie f [tʰiːf] | Old Germanic [ p ]> Old High German [ f (ː) ] |

| Old Franconian [ t ]> Dialectal Franconian [ s (ː) ] | Wa ss he [vɑsɐ] | wa t ōr [wɑtɔːr] | Wa ss he [vasɐ] | Urgermanisch [ t ]> Old High German [ s (ː) ] |

| Old Franconian [ k ]> dialect Franconian [ x (ː) ] | maa ch e [maːχə] | ma k ōną [mɑkɔːnɑ̃] | ma ch s [maχən] | Old Germanic [ k ]> Old High German [ x (ː) ] |

| Old Franconian [ p ]> dialect Franconian [ p ʰ ] | P add [pʰɑtʰ] | p aþaz [pɑːθɑːz] | Pf ad [p͡faːtʰ] | Urgermanisch [ p ]> Old High German [ p f ] |

| Old Franconian [ t ]> Dialect Franconian [ ʦ ] | z o [ʦo] | t ō [tʰɔ] | z u [ʦu] | Original Germanic [ t ʰ ]> Old High German [ ʦ ] |

| Old Franconian [ ð ]> Dialect Franconian [ d ] | d o [do] | þ ū [θuː] | D u [you] | Early High German [ θ ]> Old High German [ d ] |

| Dialect Franconian [ s k ʰ ]> Old Cologne [ ɕ ] | Fe sch [fɛɕ] | fi sk az [fɪskaːz] | Fi sch [fɪʃ] | Old High German [ s k ʰ ]> Middle High German [ ʃ ] |

| Dialect Franconian [ ɣ ]> Old Cologne [ j ] | G old [joɫtʰ] | g ulþą [ɣulθɑ̃] | G old [gɔltʰ] | Old Germanic [ ɣ ]> Old High German [ g ] |

| Dialect Franconian [( ɛ- , œ- , e- , ø- , i- , ɪ- , ʏ- , y- ) x ]> Old Cologne [( ɛ- , œ- , e- , ø- , i- , ɪ- , ʏ- , y- ) ɕ ] | i ch [ɪɕ] | i k [ik] | i ch [ɪç] | Old High German [( ɛ- , œ- , e- , ø- , i- , ɪ- , ʏ- , y- ) x ]> Middle High German [( ɛ- , œ- , e- , ø- , i- , ɪ- , ʏ- , y- ) ç ] |

| Old Cologne [ l ]> Kölsch [ ɫ ] | Sa l z [zɑːɫts] | sa l tą [saltɑ̃] | Sa l z [zalʦ] | % |

| Old Cologne [ n ]> Kölsch [ ŋ ] | mi ng [mɪŋ] | mī n az [miːnaːz] | mei n [main] | % |

| Old Cologne [ ʁ ]> Kölsche Elision des [ r ] | Gaade [jɑːdə] | ga r dô [ɣɑrdɔ] | Ga r th [gaʁtʰən] | New High German [ r ] (majority)> New High German (20th century) [ ʁ ] (majority) |

| Foreign language [ s - ] > Cologne [ ʦ- ] | Z out [ʦauːs] |

s auce [soːs] (French) |

S auce [zoːsə] | Foreign language [ s- ]> New High German [ z- ] |

| Legend: completely / partially colored lines = second sound shift (phases 1–4) and a further sound shift: blue = phase 1 ( fricative ); yellow = phase 2 ( aspiration , affriction ); green = phase 4 (= plosivation ); red = phase 5 ( palatalization ) | ||||

Especially in the final position is the l (as in the "eel" - the "Old") dark colored (technical terms: "Uvularisierung" or velarisiert , similar to the English l in "well").

The "I" - I seem to be too good for inexperienced ears: isch, wischisch, Bööscher. In fact, the Kölsch "Ich-Laut" is a clearly distinguishable variant of the Sch, which is spoken with rounded lips with the same point of articulation, just like the English counterpart is spoken with rounded lips. So for non-Cologne residents it is a question of allophones , while for Cologne residents it seems to be two different phonemes . The fact that Cologne residents speak a “ch” instead of a “sch” in High German (“Tich” instead of “Tisch”, “Fich” instead of “Fisch”, etc.), is not an expression of the difference between the Cologne I- Loud and high German "sch", but rather to be rated as hyper- correctism and is called "Rhenish sch phobia". This is / was presumably reinforced or provoked by neighboring dialects ( Bönnsch , Südbergisch , partly Siegerlandisch ), which have an umlaut in comparison to High German to the "I" -ch.

Even if the clear phonetic difference for the word differentiation (Pech - Pesch) is practically irrelevant, it should also be found in the typeface for the sake of recognizing the words and for etymological reasons. Apparently correct spelling with sch disrupts the flow of reading. No special character is specified in the IPA phonetic transcription for this sound. According to the IPA recommendations of 1949, “£” would have been an option. In recent publications can be found [ ɕ ] ( Unicode : U + 0255), the voiceless alveolopalatalen fricative and the voiceless fricative velopalatalen [ ɧ ] (Unicode: U + 0267)

The initial g is always pronounced like j as a palatal [j]: nhd. Gold to ksh. Gold [joɫtʰ], also before consonants: nhd. Glück zu ksh. Glöck [jløkʰ], nhd. Greetings to ksh. United [jʁoːs], as well as at the beginning of a syllable to clear vowels and l and r. Nhd fly to ksh. fleege [ˈfleː.jə], nhd. Tomorrow to ksh. Morge [ˈmɔɐ̯.jə], nhd. Gallows to ksh. Gallows [ˈjɑɫˑ.jə]. After dark vowels it is usually pronounced as velares [ɣ]: nhd. Magen zu Mage [ˈmɑː.ɣə].

The final g is pronounced as [χ] after dark vowels and as [ɕ] after light vowels: nhd. Zug zu ksh. Moved [ʦoːχ], NHG. Blow to ksh. Blow [ɕɫɑːχ]; nhd. forever to ksh. forever [ˈʔiː.vɪɕ].

Intervowel or final b in High German has usually stayed with the old Franconian [v] or [f]: nhd. To give to ksh. gevve [ˈje.və], nhd. remains to ksh. bliev [bɫiːf], nhd. from to ksh. av [ʔɑf], nhd. whether to ksh. ov [ʔof].

The voiced [d] was not like the High German regularly to voiceless [t] moved. NHG table to ksh. Desch [deɕ], nhd. To do to ksh. don [don], nhd. Dream about ksh. Droum [dʁɔʊ̯m].

The initial [s] in foreign words with an initial voiceless [s] regularly became an affricate [ʦ]: nhd. Soup to ksh. Zupp [ʦʊpʰ], nhd. Sauce to Zauß [ʦɑʊ̯s], nhd. To sort to ksh. zoteere [ʦɔ.ˈtʰeː.ʁə].

An intervowel ss is spoken predominantly voiced even after a short vowel (cf. German: Fussel, Dussel): nhd. Read to ksh. read [ˈlɛ.zə], nhd. remnants of ksh. Nüsel [ˈnʏ.zəl], nhd. Console to ksh. Possument [pɔ.zʊ.ˈmɛntʰ], "to present (oneself), to place wisely" to ksh. possumenteeere etc.

A -eit (-) or -eid (-) in today's German very often corresponds to -igg: nhd. To cut to ksh. schnigge , ring the bell to ksh. lie , nhd. far to ksh. wigg , nhd. time to ksh. Zigg . If the word cannot be expanded, it will turn to ck at the end of the word, nhd. People to ksh. Gap . (cf. wigg , wigger or Zigg , Zigge ) This phenomenon, called palatalization , can also be found in other words such as nhd. wine to ksh. Wing , nhd. Brown to ksh. brung , nhd. end to ksh. Engk etc.

The pf was never created in Kölschen, instead the historically older plosive [p] is usually spoken: nhd. Horse to ksh. Pääd [pʰɛːtʰ], nhd. Whistle to ksh. Pief , nhd. Cold to ksh. Schnups or shooting . This is one of the areas in which Kölsch, like all Ripuarian languages, has remained closer to Lower Franconian to this day than to the developing High German. However, there are also some cases in which the Kölsch did not stay with the Lower Franconian p without following the German for pf; In the sum of these cases it goes further than any other Ripuarian languages; Examples are copper> suitcase [ˈkʰo.fɐ], nhd. Plant to ksh. Flanz (also Planz ), nhd. Botch to ksh. fuutele etc.

If an r occurs in front of other consonants in German, the preceding vowel is usually lengthened in Kölschen and the r is dropped: nhd. Garten zu ksh. Gaade [ˈjɑː.də], nhd. Card to ksh. Kaat , NHG. Like to ksh. gään [jɛːn], nhd. thirst for ksh. Doosch .

Some consonants aggregations, especially in foreign words are not entered into the Kölsche and replaced by the Ripuarian intonation tolerated: Porcelain> Poste Ling [pʰɔs.tʰə.lɪŋ], there are both elision , and metathesis reactions , and, as in the example, combinations watch from it.

Liquid, such as l, m, n, ng, as well as s, ß, sch, v, less often j, are often spoken much longer in Cologne than in high and Dutch. This gemination is owed on the one hand to the sentence melodies, on the other hand from time to time a prosodic stylistic device that is used for emphasis and, if necessary, the transport of small meanings in word groups. A frequently observed rhythmic characteristic of language is that short vowels often follow rather long consonants, while the consonants after vowels of medium length are shorter, so that the respective syllable length remains almost identical for several syllables in a row. In addition, short syllables can often be 1: 2 shorter than the others and like to appear in groups, which makes the Cologne language seem easy to sing (compare the chorus of the song "Viva Colonia" by the Höhner ).

Voiceless or hard consonants of Kölschen are changed to voiced / soft when shifting into the middle of the word, when lengthening and (in contrast to German, but similar to the French liaison ) also with many word transitions . Typical are the transitions [tʰ]> [d], [kʰ]> [g], [pʰ]> [b], (voiceless) sch> sch (voiced), [ɕ]> [ʒ], more rarely [f] > [v]. Examples: nhd. Accordion to ksh. "Die Quetsch und der Quetschebügelgel" (with a voiced sh!), One says: "I'm going" to ksh. “I gonn”, another doesn't want to say “I don't” to ksh. "Ich ävver nit" (with a voiced ch and sounding like a word), or: "he (does not) succeed" to ksh. “Dä pack dat”, “dä pack et nit” (with a voiced [g]). The respective speech or sentence melody has a decisive influence on the absence or occurrence of such cross-word adjustments. Very similar to the French variant of the liaison, deleted consonants sometimes reappear between words connected in this way: Up in the closet = Bovve, em Schaaf; however: "Put it in the top of the cupboard" to ksh. "Bovve (n) en der Schaaf läge"; "You will find there ..." to ksh. "Ehr fingt do ...", "there you will find ..." to ksh. "Do fingt Ehr ..." (with a voiced [d]). Occasionally, short epentheses are inserted between words of the liaison, spoken individually, that is, emphasized: "the old woman" = "de Aal", but in the flow of the sentence: "It was not the old woman." To ksh. “Die Aal wor et nit.” [Diːjɑːɫ vɔːʁət nɪtʰ] - as long as the emphasis is neither on “the” nor on “Aal”.

grammar

items

Certain articles

|

|

In contrast to German, the Kölsche has two expressions of the specific articles . These are used differently.

* Here the “von-dative” as a substitute for the possessive genitive

Unstressed form

The unstressed form is used when the noun in question should not be emphasized or emphasized. This occurs u. a. in the following situations:

- When people talk in general: The / D'r Minsch can do everything, wat huh. (Man can do anything he wants.)

- If the noun is unique: De Ääd es round. (The earth is round.)

- For proper names: Der / D'r Jupp wonnt en Kalk. (Josef / Jupp lives in Kalk.)

In Kölschen, proper names are always mentioned with the article, which has also been carried over into the high German usage of many Cologne residents. Female first names always have the article in the neuter:

Et Züff es om Nüümaat. (Sophia / Züff is on Neumarkt .)

Emphasized form

In many cases, the stressed form resembles a demonstrative pronoun , as it is mainly used for the stressing of nouns:

The man stole the woman. (The man stole from the woman.)

It is also used when reference is made to one of several possible or already known objects:

Es et dat grandchildren? (Is it that grandchild?)

Up here he's talking about a particular grandson of the person. If the unstressed article is used in the example ( Es dat et Enkelche?) , The question is not about a specific, but about any grandchildren.

Indefinite article

| Singular | Masculine | Feminine | neuter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | ene | en | e |

| Genitive | vun enem | vun ener | vun enem |

| dative | enem | ener | enem |

| accusative | ene | en | e |

The indefinite article has the same usage here as in German. In the spoken language, the “e” at the beginning is often deleted.

genus

In many cases the gender corresponds to that of German, but there are a few exceptions, which are disappearing more and more due to the high German influence. Here is a selection:

| Kölsch | Standard German |

|---|---|

| De Aap | The monkey |

| De Baach | The brook |

| Et cheek | The cheek |

| The brell | The glasses |

| Et Dark | The window |

| De Fluh | The flea |

| De Muul | The mouth |

| De Rav | The Raven |

| Et vent | The salad |

| De Schuur | The chill |

| De Spann | The instep |

| Et bacon | The fat |

That can go very far: De Aap ensures that a man with this nickname is of course given the feminine article, even if his gender remains otherwise male ( Constructio ad sensum ): " The Aap hät singe Schwejevatte tied up " (not: " her Schwejevatte "). More recent word creations sometimes have no clear gender: der Auto , de Auto . “ Et Auto ” was only gradually adopted from Standard High German in the 1960s and 1970s. As mentioned above, female first names have the neuter article. Depending on the article, the words can have a difference in meaning, as in the case of the Kall (Gerede) and de Kall (Rinne).

Nouns

| genus | case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| m. | Nominative | the man | de men |

| m. | Genitive | vum man | vun de men |

| m. | dative | the man | de men |

| m. | accusative | the man | de men |

| f. | Nominative | de woman | de woman |

| f. | Genitive | vun the woman | vun de Fraue |

| f. | dative | the woman | de woman |

| f. | accusative | de woman | de woman |

| n. | Nominative | et Huus | de Hüser |

| n. | Genitive | vum Huus | vun de Hüser |

| n. | dative | the Huus | de Hüser |

| n. | accusative | et Huus | de Hüser |

Kölsche is characterized by simplifications compared to the grammar of (historical) Standard German. There are 3 cases, the genitive only exists in a few expressions like Modderjoddes (Mother of God). Verbs and expressions with a genitive object almost always have a dative object in Kölschen:

Despite the Rähn (despite the rain). The genitive as an indication of possession is formed with the preposition vun + the dative:

Dä ring vum (vun dem) Züff. (Sophia's Ring)

For the sake of simplicity, this genitive has been added to the tables. This “vonitive” has also established itself in standard German. There is another way of indicating a person's possession, namely using the possessive pronoun : Mingem Broder si Huus. (literally: "My brother's house"). This construction does not exist in High German, but some Cologne residents translate it into High German.

It is also noticeable that in contrast to German, no additional letters are appended to the words in the various cases. Nominative and accusative are even identical in all genera.

The plural formation occurs most often through -e: the horse, the horses> dat Pääd, di Pääde; or - (e) re: the thing, the things> dat thing, the things / things; more rarely through -te: the young man, the young men> da Poosch, di Pooschte; even more rarely through - (ch / t / k) (e) r: the group / people, the groups of people> di Lück, di Lückcher; or - (e) n: the door / the gate, the doors / gates: di Pooz, de Poozen, the shoe / shoes: dä Schoh, di Schohn (closed o); for loan and foreign words also as in the original with -s: the code, the codes> dä Kood, di Koodß; or irregularly and with umlaut: the post, the posts> dä Pohl, di Pöhl (open ö); the coffin, the coffins> da Sarrsch, di Särrsch; absolutely without equivalent in German, such as: the dog, the dogs> da Hongk, di Höngk (closed o and ö). There are also identical shapes for singular and plural: the cake, the cake> dä Koche, the koche (long closed o with sharpening ), the dog, the dogs> dä Möpp, the Möpp (e), the bill, the bills > da Sching, die Sching; as well as occasional combinations of umlaut with the addition of endings, das Scheit, die Scheite> dat Holz, di Holz (gutturalized, closed o / ö).

Reduced forms are often encountered and are formed in the singular with -che or -je, depending on the preceding sound: Wägelchen> Wäjelche, Tässchen> Täßje. In the plural, an r is added: several birds> Füjjelcher.

Proper names , especially family names , form a special adjectival form similar to the old German genitive: Katharina Pütz> et Pötze Kätt; Schmitz family> de Schmitzens; the children of the family or clan Lückerath> de Lükerohts Pänz; the Fahls family with friends and relatives> dat Fahlses Schmölzje. Also with nicknames and social role designations: Müller's Aap ; de Fuzzbroojsch's Mamm.

In place and landscape names , the German forms an undeclined adjective- like form that ends with -er . Kölsche knows them too, but with somewhat more complicated educational rules and fewer applications: Deutzer Bahnhof > Düxer Baanhoff, Göttingen University> Jöttinger Uni and not * Götting en er ; however: Olper Straße> Olp e n er Strohß; Eifeler Straße, Eifeler Bauer> Eejfelstrohß, Eejfelbuur; Bonner Münster> et Bonnsche Mönster, but: Bonner Straße> Bonner Strohß (with closed o). Street names that deviate from the German rules are often the official names in the urban area in High German spelling and sounding.

In many Cologne verbs, the infinitive ends in -e: set e (set). But there are also verbs with the ending -n: sin n (to be), ston n (to stand).

Verbs

conjugation

Present

As in German, there are regular and irregular verbs in Kölsch. The regular ones can be divided into two groups. The first group are the verbs whose stems end in -r, -l, -n, or a vowel. These are conjugated as follows:

| person | pronoun | verb |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person Sg. | I | spill e |

| 2nd person Sg. | do | spill s |

| 3rd person Sg. | hä / se / et | spills t |

| 1st person Pl. | mer | spill e |

| 2nd person Pl. | honest | spills t |

| 3rd person Pl. | se | spill e |

| Polite form Sg. And Pl. | Honor | spills t |

| Imperative sg. | spill! | |

| Imperative pl. | spill t ! |

The second group are all other regular verbs. These are identical to the first, but the -t is missing in the third person singular. E.g . : Hä käch . However, there are exceptions, depending on the ending of the word stem:

- -dd: omission of a d in the 2nd pers. Pl .: Ehr tredt instead of eht tred d t

- -t: Retention of the word stem in the 2nd pers. Pl .: Ehr kaat instead of Ehr kaat t .

- -cht: elimination of the t in the 2nd and 3rd pers. Sg .: do bichs, hä bich instead of do bich t s, hä bich t .

- Short vowel + st: conversion of the t to an s in the 2nd and 3rd pers. Sg .: do koss, hä kos s instead of do kos t s, hä kos t .

- Long vowel + st: omission of the t in the trunk in the 2nd and 3rd pers. Sg .: do taas, hä taas instead of do tass t s, hä taas t .

- -ft: conversion of the t into an f in the 2nd and 3rd pers. Sg .: do döf f s, hä döf f instead of do döf t s, hä döf t .

- -ng: add a k in the 3rd person sg .: hä push k instead of hä push.

- -m: add a p in the 3rd pers. Sg .: hä küüm p instead of hä küüm.

- -ß / -s / -z: Retention of the word stem in the 2nd person. Sg .: do kros instead of do kros s .

preterite

The past tense or imperfect tense is often replaced by the perfect tense in oral use, with the exception of auxiliary verbs . However, there is also a possibility to form this in Kölschen:

| person | pronoun | verb |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person Sg. | I | spill te |

| 2nd person Sg. | do | spill tes |

| 3rd person Sg. | hä / se / et | spill te |

| 1st person Pl. | mer | spill te |

| 2nd person Pl. | honest | spill tet |

| 3rd person Pl. | se | spill te |

| Polite form Sg. And Pl. | Honor | spill tet |

As in German, there are also irregular verbs in Kölschen whose stem vowels change into the past tense when they are formed.

Perfect and past perfect

The perfect tense is very common in Kölschen, since the past tense is often avoided in parlance. It is formed using the participle and the corresponding auxiliary verb ( sin or han ). In the perfect tense the present tense of the auxiliary verb is chosen, in the past perfect tense one uses the simple past tense

| person | pronoun | Verb (with auxiliary han ) | Verb (with auxiliary sin ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person Sg. | I | han (hatt) jespil t | ben (wor) jerann t |

| 2nd person Sg. | do | häs (hatts) jespill t | bes (wors) jerann t |

| 3rd person Sg. | hä / se / et | hät (hatt) jespill t | it (wor) jerann t |

| 1st person Pl. | mer | han (had) jespill t | sin (wore) jerann t |

| 2nd person Pl. | honest | hat (hatt) jespill t | sid (word) jerann t |

| 3rd person Pl. | se | han (had) jespill t | sin (wore) jerann t |

| Polite form Sg. And Pl. | Honor | hat (hatt) jespill t | sid (word) jerann t |

Others

Personal pronouns and articles related to persons or used demonstratively are reduced to the masculine and neuter form: the small> dat small; Can she do that? > May et dat? / May dat dat? Unless one speaks of a person whom one sings: Frau Schmitz> die Schmitz; Is she coming too? > Kütt se och? / Kütt die och? Similar to Dutch, the use of the demonstrative pronoun as a pronounced personal form is typical for Kölsch: Kütt d'r Schäng? - I think huh kütt. / Ävver klor kütt da! It is stamped in the form of yours: Wat maat Ühr / Ehr esu? > How are you doing?

A special feature is a reflexive that is unknown in High German and can be used to clarify certain activities: he had eaten a roll. > Dä has sijj e brothers jejesse. In certain actions it is inevitable: She is praying. > Et es sijj am Bedde. It is mainly found when the “beneficiary” or “beneficiary” of an activity is the acting person and there is no interaction with other people.

Another peculiarity is the pronoun er , which, like in Dutch, stands for an indefinite number of something specific, previously mentioned. An answer to the question of how many children you have could be: “ Ech hann_er keine ” <I don't have any, Dutch: “ Ik heb er geen ”. An antiquated German can serve as a donkey bridge : "I don't have any of them."

Similar to this form is the polite request that bypasses the direct imperative: Please pass me the book. > Doht mer dorr_ens dat Booch erövver jävve. Instead of "Please", the Kölsche prefers to say "Be (s) so good" <"Bes / sidd_esu joot", which, depending on the situation, either introduces a request or is attached to it. It has a strong undertone of gratitude, among other things with “Ehr sidd_esu joot för mesch.”> “You are so good to me!” You can also express your thanks.

There is also no comparison word “als” in Kölschen; instead, “how” is used ( better than nothing instead of better than nothing ).

The Kölsche knows the gerund , the so-called Rhenish form . He is sleeping at the moment. > Have it at the castle. It is used for permanent states that can be changed or of limited duration. The second form of doing with the infinitive is used for ongoing actions or states : He likes to cook. > Ha deit jään cook. It describes the lasting, mostly of a more fundamental meaning, which is not expected to change, or at least not soon.

In addition to the noun forms of verbs commonly used in Lower Franconian and High German, such as: laache> dat Laache (laugh) or: blende (blenden)> de blende, Kölsch has another one that is far from being used in German. Spöle (rinsing) becomes dä Spöl (the items to be washed and the task of washing), wöhle (rummaging) becomes dä Wöhl (burrowing, mess), hanteere (handling, handling) becomes dä Hanteer (handling), brölle ( roar, scream, shout) becomes da Bröll (shout, (shouting / up) scream, roar, roaring), klaafe (talking) becomes da klaaf (entertainment) and so on. Not all verbs form this form, but about all of them for concrete human activities and functions that do not require prefixes. It should be noted that words derived in this way are always masculine and endless . So dä Brand (fire), de Fahrt (drive) and de Pavei (pavement) do not fit, but dä Pavei (pastoral work (s)), from paveie (paving), corresponds to this educational law. It is also widespread in Lower Franconian and Dutch.

Speech history

Endings (-e, -n, -t) are mostly deleted : week> week, girl> girl, power> Maach, power> maat, market> maat.

The interlocking of words pulled together as in the French liaison is common. Example: "Clear the table" becomes "Rüüm der Desch av", with the -sch becoming voiced (as in Journal) and flowing into the opening vowel when the stress in this sentence is on the "table". This sandhi is usually not taken into account when writing. The well-known sentence from the so-called “ Rhenish Basic Law ” “Et es, wie et es” (It is, as it is) softens the -t almost to -d, so that the liaison works better (for example: “eddés, wie- eddés “, alternative spelling: ed_eß wi_ed_eß). As in French, parts of the word can be dropped or changed in the liaison: for example, one hears “lommer”, “sommer”, which corresponds to “loss mer”, “solle mer?” (Let's ... shall we?), Occasionally written as “lo 'mer "," so'mer ". Especially when speaking quickly, entire syllables can merge into an almost inaudible sound or disappear completely: a “Krißenit!” For “[Dat] Kriss De nit!” (You don't get that!) Takes less time than the omitted “Dat” both i-sounds are extremely short, the e is almost inaudible. However, in the Cologne liaison not only letters or parts of syllables are omitted, phonemes can also be added, which is usually not taken into account when writing. For example, "Di es wi enne Ässel" (she is like a donkey) is spoken like: "Dii j éß wi j enne Ässel" (the ss is voiced!)

To simplify the flow of words, a word is sometimes prefixed or inserted with an e: so> (e) su, up> (e) rop, down / down> (e) runger / (e) runder / (e) raff, milk > Mill (e) sch, five, eleven, twelve> fön (ne) f, el (le) f, twelve (le) f. Unlike in many other languages (for example Japanese, Italian, French and Spanish), this has nothing to do with the fact that it is found difficult to pronounce words without this initial sound. On the contrary, it is an option that is often left to the speaker. Occasionally the meaning of a word can depend on the stress in the sentence: “Dat hät dä (e) su jesaat”> “He said that explicitly / literally”, while “Dat hät dä (e) su je saat ”> “That has he (probably) babbled along like that ”. These "soft" epentheses are occasionally used to adapt the rhythm or melody of words and sentence types to one another, and are at least as often pure stylistic devices.

Liquid , like l, n, ng and more rarely m, r, after a not-long vowel are often pronounced like vowels in Kölschen. However, this is not always the case and has practically no influence on the meaning of the word. However, it does determine the speaking register and possible secondary meanings of a sentence or part of a sentence. For example, in the word “Pampa” (Pampa), the m in Kölschen is always pronounced relatively long after a short a.

In the sentence “Do you should be en de pampa jon” (he may go into the pampas / disappear) - spoken without any special emphasis - you will hear a relatively factual message, but the speaker raises the volume a little at “de” and with “Pampa” a little more, at the same time with the a in “Pampa” the pitch and length of the m in Pampa noticeably lengthened, and if the second half of the sentence is a bit squeezed, then this becomes an angry, contemptuous hint of high emotionality that “Piss off!”, which is anchored in the regional colloquial language , is clearly exceeded.

The speech melody is more pronounced than in standard German. For questions, for example, the penultimate syllable is pulled down further in pitch , while the last syllable goes much higher before it drops again a little. Much more than in Standard German, modalities and nuances of meaning (up to the point of the opposite!) Are conveyed via changed intonation, additional vowel extensions and changes in the pitch of the voice. Then there is the so-called sharpening . Kölsch shares this intonation phenomenon with several other "Western languages " such as Eifeler Platt, Luxembourgish, South Lower Rhine and Limburgish. (The latter in the Netherlands, Belgium and in Selfkant). The sharpening is a special type of vowel emphasis : the vocal tone drops very quickly, sometimes so strongly that it becomes inaudible for a fraction of a second. Without sharpening, the tone of the voice only goes slightly downwards and immediately returns upwards. The sharpening is sometimes even different: "schlääch" (schlääch) without sharpening means "bad", "Schläg" (schläähch) with sharpening means "blows". Liquids following a short vowel (l, m, n, ng, r) are often included in the tone progression of the sharpening and thus form a kind of tonal diphthong, for example in "Jeld" (money) and "Jold" (gold), " Hungk "(dog)," Orjel "(closed O) (organ) etc.

The superimposition of word melody and sentence melody gives the Kölschen its typical " singsang ".

variants

Stadtkölsch

Today's Kölsche is historically the result of a constant mixing and overlapping of different language currents, which is certainly one of the reasons for its wealth of forms. Cologne's two-thousand-year-old position as a trading metropolis, the opening up to the surrounding area and the incorporation of the past two hundred years have brought together different languages, some of which still have an effect today, so that forms coexist, are used and understood without being assigned to a specific origin within the current urban area to become, although this is possible in individual cases. So you can go downstairs as "de Trebb_eraf" "de Trepp (e) runder" "de Trepp (e) runger" and go back upstairs with "de Trap (e) rop" like "de Trebb_erop" and "Ming Auto, Ding Auto ”as well as saying“ mi Auto, di Auto ”(my car, your car) and just as“ pale, pale, pale ”as“ pale, pale, pale ”for German pale, pale, pale. Note that despite the same spelling in two in the second case, the pronunciation of the Cologne words differs so significantly from that of the German words that they can hardly be assigned to one another by an inexperienced person.

In any case, the Kölsche Lexik is developing towards High German and discarding old stems and forms. Adam Wrede , for example , who collected a language level from around 1870 to around 1950, marks a not inconsiderable part of the words in his dictionary as outdated or out of date. It is likely that parts of the grammar will disappear at the same time, at least a comparison between the 435 different conjugations cited by Fritz Hönig in 1877 and 1905 with the grammar by Christa Bhatt and Alice Herrwegen from 2005, which records 212 conjugations.

Landkölsch

The Landkölsch dialects in the immediate vicinity are going through a similar development more slowly and are therefore at an earlier stage. They can usually be easily distinguished from the city dialect by phonological features . Only in the north of Cologne can you find larger Stadtkölsch-speaking areas on both sides of the Rhine. How far into the surrounding area, and whether neighboring dialects are still perceived as "Kölsch", often depends on the position of the viewer and is accordingly handled inconsistently.

Other Kölsch

In the district of Dane County in the State of Wisconsin ( USA ), a local variety of Kölschen was said a century ago, among other languages. In 1968 there was at least one speaker who did not pass on his mother tongue to his children.

Cologne vocabulary

What makes learning Kölsch difficult is the special vocabulary that has Low and High German, but also Latin, French, Dutch and Spanish influences. Some vocabulary is only used in the Cologne area and is available as isolated words that no other dialect has. However, these are becoming less and less common in everyday language. Examples of vocabulary are:

| Standard German | Kölsch | Word origin | annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Storage room, tiny room, hermitage | Kabuff, Kabüffje | either via Neuniederländisch kombof ("Notküche; Abstellraum ") or via the Altkölniche from an unknown old Franconian term | |

| monkey | Aap | from Old Cologne * ape , from Old Franconian * apo , from Ur- Germanic * apô , from Ur-Indo-European * képmn ursprünglich (originally: the brown) (cf. nl. aap , eng. ape , arm. կապիկ (kapik), lit. be žiõnė , hin. कपि (kapi), Wal. Epa , Russian. Обезьяна ( obe zʹjána), fin. Apina ) |

see also Müller's Aap |

| blackbird | Määl | of historic colognian * merel from Altniederfränkisch merol * , from Vulgar Latin merola * , from the classical Latin merula , from early Latin * mesola from Urindogermanisch * mesólh₂ (see. nl. merel , Fri merle , whale. mwyalch , Alb. mëllënja , pdt. Aumsel ) |

|

| Cowardice | Anxiety stressers | Determinative compound from bang (bange, anxious), from Old Cologne * bange , from Old Franconian * bangi , from Old Germanic * bengiz , from Indo-European * peh₂enǵʰis , and Dresser ("Scheißer"), from Dress , from Old Cologne * drees , from Old Franconian * third , from Urgermanisch * dritz ("Notdurft"), from Urindo-European * dreds ("Diarrhea") | |

| handsome, stately | state | of historic colognian * State of Altniederfränkisch * stats from Vulgar Latin statos * , from classical Latin status , from early Latin * statos from Urindogermanisch * steh₂tos (see. nl. statig , nd. gangstaa lish ) |

frequent phrase: Staatse Käl (handsome guy, great guy) |

| work, handle | brassele | perhaps related to high German patter | |

| Anger, stress, work | Brassel | perhaps related to high German Prassel | |

| "Offhand", "shot from the hip" |

us the Lamäng | From French la ("die") + main ("hand"), from Old French la , from Vulgar Latin illa ("the"), from Classical Latin illa ("she"); from Old French main , from Vulgar Latin * manos , from Classical Latin manus , from Early Latin * manos ("hand"), from Urindo-European * manós ("hand, fuse") | |

| (pay), "sheet" | lazze | probably with the idea of progress, that "the money leaves" when you pay Etymologically: from Middle High German lāzzen , from Old High German lāzzan , from Proto-Germanic * lētaną from Urindogermanisch * ledonóm ( "leave to remain alone") |

|

| Beer waiter | Köbes | Cologne form of "Jakob", from Classical Latin Iacobus , from Ancient Greek Ιάκωβος (Iákobos), from Hebrew יַעֲקֹב (Ja'aqov; "Felse") | the waiter in the Rhenish brewery, typically wearing a blue apron |

| Beer tap | Zappes | from Old Cologne * zappes , from Old Franconian * tappis , from Ur- Germanic * tappiz , from Ur-Indo-European * dabis ("Zapfer") (compare Dutch tapper , English tapper [ˈtæpəʳ]) |

|

| Blueberry; Wild berry | Worbel |

Anagram of Old Cologne * woldbere with omission of the e, from Old Franconian * woldeberi , from Ur- Germanic * walþiwibazją ("forest berry"), n , formed from Indo-European * kweltos ("meadow, hair") and * bʰesiom ("berry") plural also Wolberre [ˈƲɔɫˑbəʁə] |

|

| Blood sausage | Flönz / Blohdwoosch | Blohdwoosch: from Old Cologne * blodworst , Old Franconian * blodworst , from Urgermanic * blōþōwurstiz , formed from Urindo-European * bermanlatom and * wr̥stis | see also Saar enz "Flönz" , compare Dutch bloedworst |

| Well, pond, puddle | Pütz | from Altkölnisch * puts , from Altfränkisch * put , from Urgermanisch * putjaz ("Brunnen, Grube"), from Classical Latin puteus , from Early Latin * poteos , from Urindo-European * poteos ("Brunnen, Grube, Zisterne ") (cf. French puits (Brunnen, Grube, Schacht); see also in Dutch: put and in Ruhr German : Pütt (Schacht, Grube) or High German puddle ) |

the most common surname after "Schmitz"; |

| (female breast | Memm | from Old Cologne * memme , from Old Lower Franconian mamma , from Latin mamma ("breast, mama"), from Urindo-European * méh₂-méh₂ (cf. Dutch mam (a) ("mama"), mamma ("breast"); French mamman ( "Mother"), Turkish meme ("(female) breast")) |

|

| Bread and butter | Botteramm | of historic colognian * boterham from Altfränkisch * boterham , composition * boter , by means Latin būtȳrum , ancient Greek βούτυρον (boutyron), a composition of βοῦς (bous) of Urindogermanisch * gows ( "cow") and τυρός ( "túrós" ), from Urindo-European * teukos ("fat"), and the short form * ham from * happan ("Happen"), onomatopoeic for a bite | see. in Dutch: boterham and in Limburg : boteramm |

| fool | Blötschkopp, Doll, Doof, Jeck, Tünnes, Tring, Verdötscht, Dötsch | 1) Blötschkopp: from composition from Blötsch ("Delle"), onomatopoeic for the impression, and Kopp ("head"), via Middle High German head ("drinking bowl") from Middle Latin * cuppa , via Late Latin from Classical Latin cūpa ("cup "), from Urindo-European * keuph₂ (" sink ") 2) Doll (" crazy "): from Old Cologne * dole , from Old Franconian * doli , from Ur Germanic * duliz , from Urindo European * dl̥h₁nis 3) Jeck (" Silly "): from historic colognian * Jeke from Altfränkisch * geki , from Proto-Germanic * gekiz from Urindogermanisch ǵʰeǵʰis 4) Tünnes (Stupid): kölsche form of Anton , from classical Latin Antonius , from Ancient Greek Άντώνιος (Antonio; "Priceless"), composition of ἀντἰ- ( anti-; "against"), from Urindo-European * h₂énti ("at, near, before"), and ὤνιος (onios; "for sale"), from Urindo-European * onios 5) Tring (Katharina): Cologne form of Katharina , from ancient Greek Αικατερίνα (Aikaterina; "the pure, sincere") |

|

| Dragons | Pattevu (e) l | ||

| push pull | däue / trecke | 1) däue: from Old Cologne * duwen [dyu̯ən] ("push, press"), from Old Franconian * duwan , from Ur Germanic * dūwijaną , from Ur Indo-European * dòwijonóm ("press") trecke: from Old Cologne * trecken , from Old Franconian * trekan , from Ur- Germanic * trakjaną , from Ur-Indo-European * deregonóm ("to pull") |

has equivalents in Low German and Dutch: duwen , trekken |

| Knuckle of pork, pork knuckle | Hammche | Diminutive of historic colognian * hammering from Altfränkisch * hammo , from Proto-Germanic * hammo from Vorgermanisch * hanamō from Urindogermanisch * kh₂namn̥ ( "bacon, ham") | |

| pea | Ääz | ||

| tell | deferrals | from Altkölnisch * verzellen , from Altfränkisch * fartellan ("tell"), a combination of the prefix * far- , from Urgermanisch * fra- ("weg, fort"), from Urindo-European * pro ("vor (ne)"), and from * tellan , from Urgermanic * taljaną ("counting, numbering; telling"), from Urindo-European * delonóm ("calculating, aiming, adjusting") | has equivalents in Alemannic : verzelle , in Palatine : verzääle in Low German and Dutch: vertellen ; in English: to tell |

| something | jet | from Altkölnisch * jedde , from Altfränkisch * joweder , composition from Urgermanisch * aiwaz , from Urindo-European * oywos ("always"), and from Urgermanisch * hwaþeraz ("who, was"), from Urindo-European * kʷòtoros | has equivalents in the Franconian dialects and in Westphalian as well as in Dutch iets |

| Faxing, fussing, standing in line, effort, inconvenience, unwanted actions | Fisematente, Fisematentcher, Fisematenscher | plural only: fisimatents | |

| flirt | Fisternöll, Höggelsche | ||

| Tailcoat | Feces | short, open ö | from English cut , (older English pronunciation) |

| Curmudgeon | Knießkopp, Knießbüggel, Ääzezäller, Hunger eater | ||

| Luggage, also: kin, relatives | Bajasch / baggage | from French bagage , from Old French bagage ("luggage"), from bague ("bundle, pack"), from Vulgar Latin * baccus , from Classical Latin baculum ("walking stick, scepter, club"), from Urindo-European * bhekos ("rod, Club, scepter "); related to Urindo-European bhelg ("bar, plank") | |

| Greenhorn | Jröhnschnabel, Lällbeck, Schnuddelsjung | Composition from jröhn , from Altkölnisch * grone , from Altfränkisch * groni , from Urgermanisch * grōniz , from Urindogermanisch * gʰērnis ("green"), and Schnäbbel | |

| Buttocks , buttocks , buttocks | Fott, cunt | (closed o), has Alemannic equivalents | |

| trousers | Botz | has equivalents in other regiolects , cf. Ruhr area language: Buxe , North German : Büx , Büxen ; also Swedish : byxor | |

| potato | Ääpel, Äädappel | Derivation from Erdapfel , corresponds to the Alemannic Härdöpfel , in Dutch: aardappel | |

| Cabbage | Capes | see. English : cabbage , Polish , Slovak and other Slavic languages : kapusta , Luxembourgish : Kabes | |

| Child, children | Panz, Pänz | see. French: panse (belly) | |

| stud | Knopp | Dutch: knoop | |

| (he / she / it) is coming (please) |

kütt kutt ! |

Infinitive: come (short closed o), regionally also cum | |

| look (dying) sick | beripsch senselessness | originated from the abbreviation "RIP", Latin: requiescat in pace ( rest in peace ), which can often be found on gravestones | |

| ill | malad | from french: malade (to be sick) | |

| Kiss, kiss, kiss | Butz, Bützje, bütze | The original meaning of the word “brief collision” has been retained as a secondary meaning, for example in the case of a sheet metal damage in traffic: “ do hann_er sich zwei jebütz ”. | |

| Nightgown | Poniel | ||

| naked, bare | bläck, puddelrüh | ||

| nervous, restless | hedgehog | see. Dutch: "iebelig", German: "hibbelig" | |

| above | bovve | has equivalents in Low German, cf. Dutch: boven | |

| Upper bed (more precisely: feather bed) | Plümmo | from French: plumeau , used differently there today | |

| whether, or | ov | corresponds to Low German, cf. Dutch: of ; in the southern outskirts of Cologne ov is in the meaning or already unknown | |

| uncle | Ohm, ohm | z. T. regionally fading, Middle High German, equivalent to uncle and Uhme of other dialects, Dutch: oom | |

| East German / East European | Pimmock | originally supposed to be the name for guest workers during the construction of Cologne Cathedral ( Piedmont stonemasons), then used for seasonal workers from the east at the end of the 19th century, resumed in the course of immigration after the Second World War and the dissolution of the GDR , today also generally a person who has not internalized the Cologne mentality; see. also Imi | |

| Jacket potato | Quellmann, Quallmann | see. Palatine: Gequellde, Quellde | |

| Booger | Mmmmes | derived from it: Mömmesfresser | |

| talk, chat / talk, speak | kalle, klaafe, schwaade, bubbele | “Schwaade” can generally not be translated as “chat” / “chat”, even if both words are related | |

| umbrella | Parraplü | see. French: parapluie , Dutch: paraplu | |

| traveling, moving around on the go, traveling |

jackets op Jöck |

||

| redhead | fussian |

Foot also means "fox", so fox red (hear: ) |

|

| Brussels sprouts | Spruute, Sprühsche | see. Dutch: spruitjes, English: Brussels sprouts | |

| robin | Rähnvü (je) lche | literally: "rain bird" | |

| salad | Lock | (with a long open o) | |

| Dirt, dirt | Kneel, knees, knees | also for sebum-like dirt deposits, e.g. B. on glasses | |

| Liquor | Schabau | ||

| already, already, just | ald | in a shortened form of speech also ad | |

| already (once) time, (once) time | ens | same etymological stem as high German: once , cf. Dutch: eens (once, once, once) (hear: ) | |

| Much talker, (also) babbler | Schwaatlapp (e) | they also say: "Dä ka 'jooht der Muul schwahde." (He likes to talk a lot.) | |

| closet | Sheep | as in the Moselle Franconian , cf. Dutch and North German: nds: Schapp ; see also Thekenschaaf | |

| mustard | Mostert, Mostrich | from old French: mostarde (French: moutarde), also widespread on the Lower Rhine, Dutch: mosterd , also in Lausitz: Mostrich | |

| parasol | Pasolah, Parsolee | see. French: parasoleil , Dutch: parasol | |

| Sparrow ( house sparrow ) | Mösch | see. French: mouche (fly), Dutch: mus , Slavic : Mucha | |

| Gooseberries | Coronzele | ||

| Street girl | Sidewalk | word made up of: pavement , French loan word (sidewalk) and Schwalv ( swallow ); see. German: Bordsteinschwalbe | |

| Quarrel, a permanently bad relationship | Knees | ||

| straw | Struuh, struuh | ||

| Defiance, spirit of contradiction, anti-attitude, unwillingness; sour or bitter taste | Tailcoat, Vrack | ||

| examine, look closely | create | see. English: inspect | |

| on the go, on tour, on the move, on the move | op Jöck | ||

| Relationship, love affair | Fisternöll | ||

| insane | jeck | often to be found, probably because of the carnival girls; Dutch: gek | |

| Inclination, confidence, desire | Fiduuz | from Latin: fiducia | |

| Cronyism, nepotism , "felt" | Clique | actually ball, cf. Kölscher Klüngel

Dutch: klungel |

|

| Electoral Cologne | Imi | von imiteete Kölsche (imitation Cologne) (since the time after the Second World War; became well known outside the city through the song by the Krätzchensinger Jupp Schlösser “Sag ens Blotwoosch” from 1948). | |

| savoy | Schavuur | from Savoy cabbage | |

| plums | Squeeze | also for example in the Palatinate; Pinch in Lorraine | |

| Plum cake | Quedschekooche | ||

| Plums | Promme | compare dutch: pruimen | |

| plum cake | Prummetaat | ||

| onion | Öllsch, Öllisch, Öllije | Dutch: uitje |

There are words without a suitable equivalent in Standard German:

| Standard German | Kölsch | annotation |

|---|---|---|

| Confrontation, argument, explanation, dispute, row, argument, explanation | Explezeer | see. French: expliquer , English: to explicate |

| - | stievstaats | This combination of staats (glorious, stately, “pimped up”) with stiev (stiff, immobile, motionless / dead, superior, impersonal / formal, but also “so drunk that he / she is no longer able to buckle and therefore falls over stretched out ”) may go back to the exercise and parading of the Prussian Rhine Army, which replaced the Napoleonic occupation in Cologne. Often used synonymously for “dressed up”, “dressed up” or “in Sunday best” . |

| - | Krangköllish | Literal description of a person whose health is poor: sick onion. |

| District, district, contact area, social / residential environment | Veedel | see. German: district ; the Berlin neighborhood comes relatively close to the Veedel . |

| Thickening, accumulation, collective / brigade, traffic jam, crowd / number | Knob | All of the words mentioned are unsuitable possible translations through a generic term. The list of specific meanings should be several hundred. In addition, there are a number of trainings, such as doing something "in the knub", that is, together. "Together" has z. B. no direct equivalent in Kölsch. |

| Dent, rotten spot, fault / pointlessness | Blötsch | (onomatopoeic) among other things the opposite of a knob; see. Dutch: blood |

| stupid, dented, dented, also in a bad mood, puffy | blotchish, blotched | |

| be reflected, jump back, hop, nudge, bump, hit | titsche | (onomatopoeic) |

| Dent, damage, mark or impression, hole or large scratch | Katsch | (onomatopoeic) A Katsch is all of the above at the same time. |

| Crack | Ratchet | (onomatopoeic) |

| angular tear in fabric | en Fönnnef | The shape is similar to the Latin digit V. |

| "The police" | de lubricant | only impersonal, v. a. in the context of unwanted checking, annoying observation, when curtailing freedom, cf. Zurich German : d 'Schmiër |

| - - - |

knibbele piddele vrimmele |

All close to the Ruhr-speaking, West- and East- Westphalian prokeln , but each much more specific, partly overlapping with High German scratching , but more specific, especially than the colloquial fumbling , partly overlapping with Low German pulen |

Some words are born from original paraphrases:

| Standard German | Kölsch | annotation |

|---|---|---|

| accordion | Squeeze bar, squeeze | Literally: (two-sided) pressure bag, "squeeze bag" would be a wrong friend |

| wagtail | Wippestätzchen | literally: Wippschwänzchen |

| bed | Lappekess | see. German: rag (or cloth) box |

| Camera | Clippers | |

| Curmudgeon | Knee bar, knee head | |

| peach | Plush | composed of plush (plush, velvet) and prumm (plum) |

| mushroom | Jewish meat | actually "Jewish meat" is no longer needed today; see. also "jüddeflesj" in Kirchröadsj , the Kerkrade dialect |

| Police sergeant | Blööh | from the French bleu , the uniform color of Prussian police officers |

| Prussian (and until the early 1970s Berlin) police helmet, top hat | Kuletschhoot | from Kuletsch ( liquorice ), because of the deep black glossy color, and Hoot (solid headgear, hat ) |

Other vocabulary arose from synonyms that are now rarely used or have different references :

| Standard German | Kölsch | annotation |

|---|---|---|

| sidewalk | Trottewar / sidewalk | French loan word, also in other West German dialects |

| Roof truss, attic, roof area | Läuv | see. German: Laube |

| Pickup / floor wipe | Gravel pest | of gravel (flooring) and pest (wiping cloth) |

| pain | Ping | see. German: Pein |

| Matches, matches | Schwävelche, Schwävele | see. German: Schwefelholz , older term for matches; see. Yiddish : levitate |

| Door, gate | Pooz | from the Latin porta , gate, cf. dutch poort . The high German “gate” is now called “Pöözje” or “Enjang” in Kölsch and can only be translated as “Pooz” in rare cases. |

| embrace | push | see. German: press close to yourself , not to be confused with high German press = kölsch deue |

| path | fott | see. German: away |

| cry | creep | related to German: screeching ; see. English: to cry |

Still other words come from common colloquial language:

| Standard German | Kölsch | annotation |

|---|---|---|

| automobile | Kess | see. German: box |

| TV | Kess | see. German: box |

| Happiness, happy | Jlöck, happy | |

| clap (out / apart) | (erus- / usenander) klamüsere | to find out by careful consideration, fumbling around with difficulty |

| crooked, scheel | peel | scheel - cross-eyed - like the well-known Cologne original Schäl ; see also: Schäl Sick |

| Sales point, (newspaper) kiosk | Büdche | corresponds to the Ruhr-speaking booth in the sense of a drinking hall |

| accordion | Squeezed comood. Squeeze | Composition of quedsche (press, press) and Komood (box-shaped, commode) |

| flat | (also) Bud | see. German: Bude , Baude |

Kölsche also knows idiomatic expressions , some of which coincide with the usual German, but by no means all:

| Standard German | Kölsch | annotation |

|---|---|---|

| That amazes me! | Lick mej am Aasch! | But this can also be the " Götz von Berlichingen quote ", it depends on the emphasis. |

| Lick my ass! | But the Naache! | Literally: push my boat! |

| It is / was in Holy Week | De Jlocke sin / wohre en Rome | The bells are quiet during Holy Week, hence the saying that the bells made a pilgrimage to Rome at that time . |

| Pants down! Show your colors! Clear text please! | Botter at de Fesch! | Literally: [give] butter to the fish! , occurs throughout Northern Germany and the Benelux . |

| It's inedible, badly disgruntled, crazy. | Dat hädd en Ääz aam wandere / aam kieme. | Literally: A pea migrates / germinates with her. |

| faint | de Bejoovung krijje | Literally: getting the talent |

literature

- Fritz Hoenig : Dictionary of the Cologne dialect. After the first edition from 1877. JP Bachem Verlag, Cologne 1952.

- Georg Heike: On the phonology of the city of Cologne dialect. Marburg 1964. (German Dialect Geography Volume 57)

- Martin Hirschberg, Klaus Hochhaus: Kölsch för anzelore. Lütgen, Frechen 1990, ISBN 3-9802573-0-4 .

- Adam Wrede : New Cologne vocabulary. 3 volumes. 12th edition. Greven Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-7743-0243-X .

- Alice Tiling-Herrwegen: De kölsche sproch. Short grammar of Kölsch-German. 1st edition. JP Bachem Verlag, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-7616-1604-X .

- Christa Bhatt: Cologne writing rules. 1st edition. JP Bachem Verlag, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-7616-1605-8 .

- Helga Resch, Tobias Bungter: Phrasebook Kölsch. (with a CD spoken by Tommy Engel ). 1st edition. Publishing house Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2004, ISBN 3-462-03557-6 .

- Helga Resch, Tobias Bungter: Phrasebook Kölsch 2 - for advanced learners. (with a CD spoken by Tommy Engel). 1st edition. Publishing house Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-462-03591-6 .

- Christa Bhatt, Alice Herrwegen: The Cologne dictionary. 3. Edition. JP Bachem Verlag, Cologne 2009, ISBN 978-3-7616-2358-9 .

- Peter Caspers: Op Kölsch - The dictionary Kölsch-High German, High German-Kölsch. Greven Verlag, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-7743-0380-0 .

- Alice Herrwegen: Mer liere Kölsch - avver Höösch . JP Bachem Verlag , Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-7616-2201-8 .

- Margarete Flimm, Florian Wollenschein: Dictionary of the Cologne dialect. Kölsch-German German-Kölsch. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2011, ISBN 978-3-8448-0659-5 .

See also

- The Rhenish hands-on dictionary of the Rhineland Regional Association

- Familienkölsch , the regional lecturer

Web links

- Various Cologne sound samples from the language department at the Institute for Regional Studies and Regional History at the Rhineland Regional Council

- Akademie för uns kölsche Sproch (with ePostcards)

- Information from Reinhard Kaaden, including extensive dictionaries

- German-Kölsch translator

- Dictionary Kölsch-German and German-Kölsch

- and comparison with other Germanic languages ( Memento from September 23, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Swadesh list for some Germanic languages, including Kölsch

Individual evidence

- ^ Regiolekt in the Rhineland. (No longer available online.) Institute for Regional Studies and Regional History of the Rhineland Regional Association, archived from the original on June 20, 2012 ; Retrieved October 10, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Dialects in the Rhineland. (No longer available online.) Institute for Cultural Studies and Regional History of the Rhineland Regional Association, archived from the original on May 3, 2012 ; Retrieved October 10, 2013 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ HF Döbler: The Germanic Peoples - legend and reality. Verlag Heyne München 1975, ISBN 3-453-00753-0 , section Franconia , p. 197 ff.

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: The Franks. Verlag Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-17-017814-4 , p. 15 ff.

- ^ Rudolf Sohm: About the origin of the Lex Ribuaria . Verlag Hermann Böhlau - Weimar 1866, pp. 1 to 82

- ↑ The weakening was mainly shown by the fact that more and more words or syllables were excluded from the shift further north.

- ^ Adam Wrede: New Cologne vocabulary. 12th edition. Greven Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-7743-0243-X , Volume 2, p. 74 above.

- ^ A b Adam Wrede: New Cologne vocabulary. 12th edition. Greven Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-7743-0243-X , Volume 2, p. 74 below

- ↑ see below a. A. Wrede: The Cologne dialect, linguistic and literary history. 1909, as well as the words marked with † (from around 1956) in Adam Wrede: Neuer Kölnischer Sprachschatz. 12th edition. Greven Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-7743-0243-X - a more recent reference has yet to be found.

- ↑ Kölsche language - Kölle Alaaf. Retrieved October 1, 2019 .

- ↑ - The Little History of Language. Kölsch. Accessed October 1, 2019 (German).

- ↑ The IPA characters [a, ɧ, ʃ] and [ˑ] are not used in accordance with the standard and the character [̯] in diphthongs is replaced by [͜].

- ↑ An exception is the song Nit für Kooche from the album Vun drinne noh drusse , which rejects the revived carnival as a theme. In this text, Wolfgang Niedecken explains his reasons for 'fleeing' from Cologne during the carnival season: “Oh, not for Kooche, Lück, I stay carnival. Nah, I'm pissing off, I'm not doing it. " (High German:" Oh, not for cake, folks, I'll stay here for carnival. No, I'm pissing off today, I'm not going to take part. ")

- ↑ Klaaf. ( Memento of the original from July 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF file; 4.22 MB) 2/2010, p. 15. (last accessed October 17, 2010)

- ↑ Elmar Ternes: Introduction to Phonology. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1987, ISBN 3-534-09576-6 , p. 116

- ↑ Georg Heike : On the phonology of the city of Cologne dialect. NG Elvert Verlag, Marburg 1964, p. 45. (German Dialect Geography Volume 57)

- ↑ It is used among other things in Georg Heike: Zur Phonologie der Stadtkölner Mundart. (Deutsche Dialektgeographie Volume 57), N. G. Elvert Verlag Marburg 1964.

- ↑ See also: Nanna Fuhrhop: 'Berliner' Luft and 'Potsdamer' Mayor . On the grammar of city adjectives. In: Linguistic Reports . Issue 193. Helmut Buske Verlag, Hamburg 2003, p. 91-108 .

- ↑ Georg Heike: On the phonology of the city of Cologne dialect. NG Elvert Verlag, Marburg 1964, pp. 73 ff., 111. (German Dialect Geography Volume 57)

- ↑ See for example: Most people in Cologne are bilingual. - Conversation of an unnamed interviewer with Dr. Heribert A. Hilgers , In: Universität zu Köln, Mitteilungen 1975. Issue 3/4, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ Alice Herrwegen: Mer liehre Kölsch - avver flöck , intensive course in the Kölsch language. JP Bachem Verlag , Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-7616-2032-2 , pp. 26, 28, 29.

- ↑ Christa Bhatt, Alice Herrwegen: The Cologne dictionary. 2nd Edition. JP Bachem Verlag, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-7616-1942-1 , p. 684 above

- ↑ Center for the Study of Upper Midwestern Countries: German Dialects in Wisconsin , as of October 27, 2010, accessed: July 8, 2015

- ↑ Kirchröadsjer Dieksiejoneer, ed. vd Stichting Kirchröadsjer Dieksiejoneer, Kerkrade, 1987, p. 139.

- ↑ Bhatt, Herrwegen: The Cologne dictionary. 2005, p. 69.

- ^ Wrede: New Cologne vocabulary. 1999, Volume 1, p. 64.