Heinrich Quentell

Heinrich Quentell († August 10, 1501 ) was a printer in Cologne.

Heinrich Quentell probably came from a north Hessian family whose name is derived from the place Quentel . Quentell may have learned the art of printing in Strasbourg. Quentell married Elisabeth, daughter of the Cologne mint master and notary Johann Helman, around 1478. In December 1478 Quentell was deferred excise duties for the import of paper. His first firmierten and dated prints date from the year 1479, all reprints of successful works mainly for university use. Severin Corsten identifies the printer of the first two printed Low German Bibles, the so-called Cologne Picture Bibles, with Bartholomäus von Unkel , against the view, mainly advocated by Ernst Voulliéme , that these Bibles are Heinrich Quentell's work . This major undertaking was shifted by a consortium around Quentell's father-in-law Johann Helman. Quentell's office was in the palace house on the cathedral courtyard, which belonged to Johann Helman. Mainly theological and philosophical texts for university use left his presses, but also liturgica. Helman and Quentell also employed contract printers and posted servants to sell books.

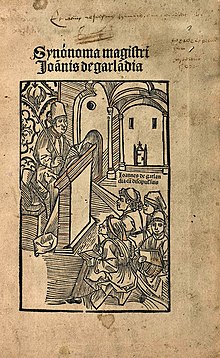

In the autumn of 1482, Quentell, coming from the Leipzig trade fair , was captured by the Lords of Hatzfeld , who were leading a feud against the city of Cologne. He was held at Wildenburg Castle for several months . From a petition addressed to the Cologne council it emerges that Quentell and his wife had five children at the time. Released from prison, Heinrich Quentell relocated to Antwerp to avoid being recaptured, where he ran a branch of the family business until 1487 at the latest. As a precaution, he refrained from mentioning his name or place in the prints of this time. He provided many of his later prints with woodcuts that were often imitated by others. A teacher-student scene, which is called Accipies woodcut because of the text shown in it, was particularly widespread. Quentell is one of the first printers to equip their works with a title page. Around 91% of his more than 380 prints have a title page.

After the death of their father, Quentell's sons continued to run the printing and publishing house as a community of heirs. During this time Ortwin Gratius began to work as a proofreader for the Quentelei. In contrast to Heinrich Quentell, his heirs increasingly also printed vernacular texts. In the Reuchlin dispute , the print shop was active on the side of the Cologne Dominicans and Johannes Pfefferkorns , which gave rise to ridicule in the dark men’s letters . From 1518 Heinrich Quentell's son Peter Quentel , who served as councilor in Cologne, began to print under his own name; In 1520 at the latest, he took over the entire shop. Peter Quentel is one of the few printers of Lutheran writings in Cologne already active in the early reformation. This is remarkable in the arch-Catholic and conservative Cologne printing industry. Elizabeth Eisenstein , referring to the research of Steinberg and Bühler , suspects that Heinrich Quentell already played an active role in providing the humanists with Latin texts. Nonetheless, he cannot be accused of being anti-Catholic in print, since he also publishes works such as Antilutherus (1525) by the Parisian theologian Josse Clicthove .

literature

- Severin Corsten: Quentel (Quentell), Heinrich (Henricus, Hinricus). In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 21, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-428-11202-4 , p. 40 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Severin Corsten: Heinrich Quentel on the move (1482/83). In: Severin Corsten: Studies on early printing in Cologne. Collected articles 1955 - 1985. Edited by Werner Grebe and Rudolf Jung. (Cologne works on library and documentation systems 7) Greven, Cologne 1985, ISBN 3774305609 , pp. 233-240.

- Severin Corsten: The beginnings of Cologne book printing. Greven, Cologne 1955 (work from the librarian training institute of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, issue 8). Also published in: Yearbook of the Cologne History Association 29-30 (1957), pp. 1-98.

- Ludwig Hepding: The Quentel early printer family from Cologne. In: Communications of the West German Society for Family Studies 58 (1970), pp. 197–208.

- Johann Jakob Merlo : Quentell, Heinrich . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 27, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1888, pp. 37-39.

- Christoph Reske: The book printers of the 16th and 17th centuries in the German-speaking area . Based on the work of the same name by Josef Benzing. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2007 ISBN 9783447054508 (Contributions to books and libraries 51), pp. 423–424 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- Wolfgang Schmitz : The transmission of German texts in Cologne book printing of the 15th and 16th centuries. Habilitation thesis, University of Cologne 1990, especially pp. 434–439 ( online ).

- Ernst Voulliéme: The printing press of Cologne until the end of the fifteenth century. A contribution to the incunabula bibliography. Reprint of the Bonn 1903 edition; Droste, Düsseldorf 1978 ISBN 3-7700-7524-2 (publications of the Society for Rheinische Geschichtskunde 24), pp. XLIV – LVI, CXVI – CXXVI ( online ).

Web links

- Prints by Heinrich Quentell in the complete catalog of incandescent prints .

- Wolfgang Schmitz: Quentel family (1479-1639), Cologne printer and publisher dynasty. In: Portal Rhenish History. Landschaftsverband Rheinland, September 30, 2010, accessed December 7, 2011 .

Remarks

- ^ Gebhard Müller: The date of death of the Cologne printer Heinrich Quentell († 1501). A handwritten tradition in the Einsiedeln Abbey Library. In: Gutenberg-Jahrbuch 80 (2005), pp. 122–125.

- ^ Ludwig Hepding: The Quentel early printer family in Cologne. In: Communications of the West German Society for Family Studies. 58 (1970), pp. 197-208, here p. 199.

- ↑ C. Plinij secundi iunioris liber illustrium virorum a condita urbe. Heinrich Quentel (Erben), Cologne 1506 ( VD 16 P 3503 ) Colophon ; Wolfgang Schmitz: The transmission of German texts in Cologne book printing of the 15th and 16th centuries. Cologne 1990, p. 434.

- ^ Wolfgang Schmitz: The transmission of German texts in Cologne book printing of the 15th and 16th centuries. Cologne 1990, p. 435.

- ^ Severin Corsten: The beginnings of Cologne book printing. Cologne 1955, pp. 81-85.

- ↑ Severin Corsten: The Cologne Picture Bibles of 1478. New studies on the history of their origins. In: Gutenberg yearbook. 32: 72-93 (1957).

- ↑ Johann Jakob Merlo: The house to the palace on the cathedral courtyard in Cologne. In: Annals of the Historical Association for the Lower Rhine . 42 (1884), pp. 61-70.

- ↑ Otto Zaretzky: The Cologne Picture Bible and the relationship between the printer Nikolaus Goetz and Helman and Quentel. In: magazine for book lovers . 10 (1906) 3, pp. 101–113, here p. 112 Appendix I (undated) ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ); Bruno Kuske (Ed.): Sources on the history of Cologne trade and traffic in the Middle Ages. Second volume 1450–1500. (Publications of the Gesellschaft für Rheinische Geschichtskunde 33) Hanstein, Bonn 1917, pp. 478-479 No. 917 (1483), p. 486 No. 946 (1484) ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ^ Klaus Militzer: The Hatzfeld feud against the city of Cologne. In: Yearbook of the Cologne History Association. 53: 41-86 (1982); Severin Corsten: Heinrich Quentel on the move (1482/83). In: Severin Corsten: Studies on early printing in Cologne. Collected articles 1955–1985. Edited by Werner Grebe and Rudolf Jung. (Cologne works on library and documentation systems 7) Greven, Cologne 1985, ISBN 3774305609 , pp. 233-240.

- ^ Johanna Christine Gummlich-Wagner: The title page in Cologne. Uni- and multivalent title woodcuts from the Rhenish metropolis of incunable printing. In: Archives for the history of the book industry . 62 (2008), pp. 106–149, here p. 116.

- ↑ Karl Riha (ed.): Dark men letters. To Magister Ortuin Gratius from Deventer. (Insel-Taschenbuch 1297) Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3458329978 , pp. 234–236 ( online ); Ludwig Hepding: The Quentel early printer family from Cologne. In: Communications of the West German Society for Family Studies. 58 (1970), pp. 197-208, here pp. 199-200; Wolfgang Schmitz: The transmission of German texts in Cologne book printing of the 15th and 16th centuries. Cologne 1990, pp. 437-439.

- ^ Christoph Reske: The book printers of the 16th and 17th centuries in the German-speaking area. Wiesbaden 2007, p. 423; Ludwig Hepding: The Quentel early printer family from Cologne. In: Communications of the West German Society for Family Studies. 58 (1970), pp. 197-208, here pp. 200-201.

- ^ Elizabeth Eisenstein: The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge 1979, here p. 206.

- ^ Ludwig Hepding: The Quentel early printer family in Cologne. In: Communications of the West German Society for Family Studies. 58 (1970), pp. 197-208, here p. 200.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Quentell, Heinrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Quentel, Heinrich |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Book printer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 15th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 10, 1501 |

| Place of death | uncertain: Cologne |