New High German language

As a modern German language (short Neuhochdeutsch , abbr. NHG. , Also NHDT. ) Refers to the most recent language level of the Germans as they actually been around since 1650 (according to other divisions from 1500). New High German is preceded by the language levels Old High German , Middle High German and - depending on the classification as a transition phase - Early New High German , which was used between around 1350 and 1650.

Differentiation from earlier language levels

Older German studies still maintain a three-way division between Old High German - Middle High German (including Early and Late Middle High German) - New High German (including Early New High German), which Martin Luther and the Reformation period and thus around 1500 see as the beginning of the New High German period. In the meantime, this three-way division has often been abandoned: the specialist literature now often assumes an intermediate period between Middle High German and actual New High German, early New High German, as the Germanist Wilhelm Scherer first introduced in his book On the History of the German Language (1875). According to Scherer, Early New High German ranges from 1350 to 1650. Sometimes the end of Middle High German and the beginning of New High German are set at 1500, usually without an early New High German phase.

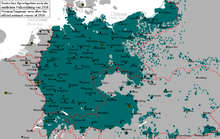

Furthermore, regional differences have to be made: In central and northern Germany , New High German has been the language of literature and printed texts since around 1650 . In the historical areas of Upper Germany ( southern Germany , Austria and Switzerland, e.g. in Upper Austria ) and on the territory of today's Swabia and Bavaria , New High German did not prevail until around 1750, thus displacing the Upper German written language previously used there . In some language histories, therefore, the epoch boundary between Early New High German and New High German for z. B. Bavaria or Austria only included around 1750.

Finally, there are also linguistic stories that start a new era after 1945, that of contemporary German.

history

Overview

In the New High German language period, a standard German language (both written and spoken) gradually developed. A large number of dictionaries, grammars and style guides that were written during this period should also be seen in this context. Furthermore, the German vocabulary expanded through literary influences and technical and political developments. Major developments in the field of phonology and morphology no longer took place.

16th to 18th century

Language norm and language society

At the beginning of the early modern period there was no uniform language standard in the German-speaking area: pronunciation and spelling are not uniformly regulated, but are just as regionally determined as the German-speaking area is politically split up into many individual countries. From the end of the 16th century, however, the educated began to discuss the question of a language standard . In this context, the question was asked which of the many regional variants had the potential for a high-level or standard German language, and there were initial efforts to establish "good German" in the form of grammars .

Luther's translation of the Bible provided important impetus for the development of a uniform standard language, but Luther's German only covered the religious sphere. If you wanted a uniform high-level language, you would also have to find a uniform German for the areas of everyday life, literature, business and administration. However, this was not the case in the 16th and 17th centuries. To make matters worse, the leading classes in Germany, the aristocratic classes, orientated themselves on the French ; French was also the language of the court.

At the beginning of the 17th century, aristocrats and learned citizens wanted to change this situation out of national feeling: their aim was to create a uniform German language and a German-language national literature . Out of this motivation, the linguistic societies emerged at the beginning of the 17th century , associations that dealt with topics such as linguistic purism, literary criticism , aesthetics and translation . One of the most important language societies in the German-speaking area was the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft , which was founded in Weimar in 1617 and was also based on European models such as the Italian Accademia della Crusca . Its members included mostly aristocrats and some commoners; Women were excluded from membership. The prominent members of the society included Andreas Gryphius , Prince Ludwig von Anhalt, Martin Opitz and Georg Schottel. Members of the linguistic societies wrote important writings that were intended to influence the development of language and literature, for example Georg Schottel is the author of the publication Detailed work from the Teutschen Haubt-Sprache (1663) and Martin Opitz is the author of the book from the German poetry .

Dictionaries and grammars

Along with the pursuit of a standard German language, there was also the production of new dictionaries and grammars. While dictionaries, grammars and language textbooks were still based on Latin in the 15th and beginning of the 16th centuries, works have now appeared that attempted to describe the German language. Schottel's detailed work on the Teutsche HaubtSsprache was an important beginning, because Schottel added a 173-page list of German root words to his work and also tried to describe an (ideal) German language form of educated men. Kaspar Stieler was able to build on Schottel's word list with his dictionary Der Teutschen Sprache, family tree and growth . Other important language standardizers who followed were Johann Christoph Gottsched and Johann Christoph Adelung . Adelung's dictionary The attempt to create a complete grammatical-critical dictionary of the High German dialect took up Gottsched's suggestion to raise Meißnish and Upper Saxon as the literary language and thus as the norm for the written language.

East Central German as a written standard

In the first half of the 17th century, the German-speaking area was still essentially divided into two parts: In the Protestant north, the East Central German written language was used, which is based on the Meißnisch advocated by language normers such as Gottsched and Adelung. In the Catholic south, south of the Rhine-Main line, the Upper German written language was still used. The Upper German written language was ultimately unable to establish itself as the second German standard in southern Germany - the influence of the north and east-central German language standardizers was too strong. The German south adopted the East Central German language standard by the end of the 18th century at the latest, also through the influence of writers such as Klopstock , Lessing and Goethe .

The influence of the writers and the Weimar Classic

In linguistic historiography, the end of the 18th century is described as a special situation for German linguistic history, because here many writers influenced the development of language by establishing a German literary language. Friedrich Wilhelm Klopstock, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing , Christoph Martin Wieland and Johann Gottfried Herder are often cited as examples of writers who were seen by contemporaries as special models for a written German language . However, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller were seen as outstanding figures in German literary history as the main exponents of Weimar Classics, the use of which contributed to the development of a fully developed written German language.

19th century

School system

With the establishment of a general school system in the 19th century as well as the grammar school with its humanistic educational ideal, the foundations were laid for introducing a large number of people to the written language and German literature. Noteworthy in this context are several publications that should help to improve teaching in contemporary German. B. From German language teaching in schools and from German upbringing and education in general (1867) by Rudolf Hildebrand and German teaching at German grammar schools by Robert Hiecke. The 19th century also saw the publication of normative school grammars and style guides for laypeople. A classic of the time was Ludwig Sütterlin's Die deutsche Sprache der Gegenwart (1900).

Origin of linguistics

In the first half of the 19th century, the discipline of linguistics established itself at universities. Previously, language policy and language maintenance were the main focus, from now on, linguistics emphasized scientific objectivity and a neutral description of language phenomena. Technical advances were also decisive for the further development of linguistics: with the invention of recording devices such as wax rollers and shellac records , it was possible for the first time to preserve spoken language and thus e.g. B. to conduct dialect research . The 19th century also saw the creation of the epochal German dictionary by the Brothers Grimm , which was begun in 1854 and further worked on by researchers who followed Grimm. The last volume was completed in 1961. The Brothers Grimm can be regarded as the founders of the science of German language and literature ( German studies ).

Developments in vocabulary

The second half of the 19th century saw many technical innovations, including the steam engine, the railroad, electricity and photography. Medicine also made great strides. As a result, many new words found their way into the German language in the 19th and early 20th centuries, such as B. Industry , Factory , Technician , Locomotive , Automobile , Gasoline , Garage , Light Bulb , Telegraph , Bacterium and Virus .

As early as the 18th century there were tendencies that worried about the "purity" of the German language and fought against access to many foreign words in the German language. Above all, the General German Language Association was active here. This struggle against foreign words, known as purism, reached its climax with Joachim Heinrich Campe's dictionary of the German language . Many proposals have been made there, but could not free himself ( appetite instead appetite , caricature instead of caricature ). But there are also a number of words that are now part of the German language thanks to Campe and Otto Sarrazin (chairman of the General German Language Association): supplicant (instead of supplicant ), platform (instead of platform ) or bicycle (instead of velocipede ).

20th century

Language normalization and standardization

As early as the end of the 19th century, efforts were made to achieve uniform German spelling. The efforts finally culminated in the Second Orthographic Conference in 1901, in which all German federal states, Austria, Switzerland and representatives of the printing and book trade took part. There a uniform spelling was established, which was reproduced in the orthographic dictionary by Konrad Duden from 1902 as an official set of rules. The next major spelling reform was initiated in the 1980s and negotiated between representatives of Germany, Austria and Switzerland. In 1998, the revision of German spelling was passed.

After they were passed, writers and intellectuals criticized these new rules heavily. Some newspapers, magazines and publishers also implemented the rule changes partially or not at all and followed a house orthography. As a result, in 2006 some rules (especially uppercase and lowercase as well as compound and hyphenation) were modified again, so that the form that was valid before 1995 (for example , I'm sorry , so-called ) is permitted again for some changed spelling .

In the field of pronunciation, too, a standardization was achieved at the beginning of the 20th century: In 1898 and 1908 conferences were convened in Berlin to agree on a uniform stage debate. The result from 1908 found its way into the 10th edition of Theodor Siebs ' Deutsche Bühnenaussprache of 1910. This language standard was slightly changed in 1933 and 1957, among other things the suppository-r ( uvulares r) was allowed, which Siebs had rejected. In the meantime, however, the oral language has changed further, among other things, less pathos and a faster speaking speed are preferred. These developments were included in the dictionary of German pronunciation (Leipzig 1964).

Language of National Socialism

In the 1920s to 1940s, political changes in Germany had a major impact on everyday language. Language was used specifically for propaganda and manipulation of the population under National Socialism. Word creations such as Hitler Youth, Association of German Girls , Secret State Police and compounds with Reichs - or Volks - such as Reich Ministry or People's Court entered everyday vocabulary . Striking are foreign words that cover up the truth, such as concentration camps or euphemisms such as the final solution to mass murder .

German language after 1945

After the division of Germany into the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic (GDR), German vocabulary was influenced by various developments in East and West. An increasing influence of American English up to everyday German can be observed in western Germany. B. teenagers , makeup , bikini , playboy . In the GDR, German was influenced to a lesser extent by the Russian language. Thanks to the official language used by the GDR leadership, words such as people's own company , workers' festival or workers and farmers state found their way into the vocabulary . You can also find loan words from Russian such as dacha and quotation words from Russian, i.e. H. single words that describe Russian things or institutions, such as Kremlin , Soviet or Kolkhoz . Many of these new forms found their way into the vocabulary of the other part of Germany through film and television and have remained part of the German vocabulary even after the reunification of the two German states.

More recent developments in the German vocabulary are mainly due to technical progress and the Anglo-American influence in film and television, so there are many loan words from English such as radar , laser , input , output , computer as well as new formations from the field of the new Media ( CD-ROM , Internet , eLearning ).

See also

literature

Linguistic perspective

- Hans Eggers: German Language History, Volume 2: Early New High German and New High German . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986, ISBN 3-499-55426-7 .

- Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 .

- Peter von Polenz: German language history from the late Middle Ages to the present . I: Introduction, Basic Concepts, 14th to 16th centuries , 2nd edition. De Gruyter, Berlin 2000, ISBN 978-3110164787 .

- Peter von Polenz: German language history from the late Middle Ages to the present . II: 17th and 18th centuries , 2nd edition. De Gruyter, Berlin 1999, ISBN 978-3110143447 .

- Peter von Polenz: German language history from the late Middle Ages to the present . III: 19th and 20th centuries , 2nd edition. De Gruyter, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3110314540 .

- Peter von Polenz: History of the German Language , 10th, revised edition by Norbert Richard Wolf. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-017507-3 .

Cultural-historical perspective

- Bruno Preisendörfer : When our German was invented. Journey to the Luther era . Galiani, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-86971-126-3 .

Web links

- New High German (schuelerlexikon.de). Retrieved October 10, 2014 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hilke Elsen: Basic features of the morphology of German. 2nd Edition. Walter de Gruyter, 2014, o. S. (e-book, see under Fnhd. , Mhd. And Nhd. In the list of abbreviations).

- ^ Bertelsmann: The new Universal Lexicon. Wissen Media Verlag GmbH, 2006, p. 191f.

- ^ Bertelsmann: Youth Lexicon. Wissen Media Verlag GmbH, 2008, p. 125.

- ↑ Hans Eggers: German Language History, Volume 2: The Early New High German and New High German . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986, ISBN 3-499-55426-7 .

- ^ Manfred Zimmermann: Basic knowledge of German grammar . 7th edition. Transparent Verlag, Berlin 2014, p. 76.

- ^ Werner Besch: History of Language; Chapter: 192 aspects of a Bavarian language history since the beginning of modern times . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1998, ISBN 9783110158830 , p. 2994.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , p. 208.

- ^ Stefan Sonderegger: Fundamentals of German Language History I. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1979, ISBN 3-11-003570-7 , p. 179.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 176–177.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 177-182.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 183-185.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 186-187.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 188-189.

- ↑ Hans Eggers: German Language History, Volume 2: The Early New High German and New High German . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1986, ISBN 3-499-55426-7 , pp. 325-349.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 208-212.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 212-213.

- ^ Peter von Polenz: History of the German Language , 10th, revised edition by Norbert Richard Wolf. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-017507-3 , p. 108.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 215-217.

- ^ Peter von Polenz: History of the German Language , 10th, revised edition by Norbert Richard Wolf. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-017507-3 , p. 108.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 219-220.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 223-224.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , p. 225.

- ^ Peter von Polenz: History of the German Language , 10th, revised edition by Norbert Richard Wolf. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-017507-3 , pp. 129-130.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 226–229.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , pp. 231-233.

- ^ Peter von Polenz: History of the German Language , 10th, revised edition by Norbert Richard Wolf. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2009, ISBN 978-3-11-017507-3 , pp. 167-169.

- ^ Peter Ernst: German language history , 2nd edition. Facultas, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3689-2 , p. 235.