German language history

The German language history goes back to the early Middle Ages back, the era in which she separated from other Germanic languages. But if you take its prehistory into account, the German language history is much older and can be represented taking into account its Germanic and Indo-European roots. German, as one of the languages of the Germanic language group , belongs to the Indo-European language family and has its origin in the hypothetical Indo-European original language . It is believed that this Indo-European language developed in the first millennium BC. Developed the Germanic original language ; the turning point here is the first sound shift , which took place in the later first millennium BC. The processes that led to the emergence of the German language spoken today, on the other hand, may not have started until the 6th century AD with the second sound shift .

The early stage in the development of German, which lasted from around 600 to around 1050, is known as Old High German . This was followed by the level of Middle High German, which was spoken in German areas until around 1350. From 1350 onwards one speaks of the era of Early New High German and since around 1650 of New High German - the modern development phase of the German language, which continues to this day. The dates given are only approximate, exact dates are not possible. As with all other languages, the development processes in German can only be observed over a long period of time and do not occur abruptly; In addition, these development processes differ in terms of their scope and speed in different regions of the German-speaking area. During the Middle High German period, specific forms of German developed in the German-speaking area, which Jews spoke to one another and were usually written with a Hebrew alphabet adapted for this purpose. A large number of borrowings from mostly post-biblical Hebrew and, to a lesser extent, some borrowings from Romansh (French, Italian and Spanish) are characteristic, while the syntactic influence of Hebrew is questionable.

Indo-European

Origin of the Indo-European languages

Similarities between different languages of Europe and Asia (for example Sanskrit ) were noticed as early as the 17th and 18th centuries; It was not until the beginning of the 19th century that linguists (including Franz Bopp and Jacob Grimm ) began to systematically research these similarities on a historical basis. They came to the conclusion that almost all languages (and thus probably also peoples) of Europe and several languages (and peoples) of Asia had a common origin. Because these related nations occupy vast territory from the Germanic peoples in the west to the Asiatic peoples in northern India, the hypothetical indigenous people became Indo-Europeans , and the language they spoke several millennia ago was called the Indo-European Original Language . Outside the German-speaking area, this developed language is usually referred to as the "Indo-European" language.

According to the current state of research, the original home of the Indo-Europeans was probably located north and east of the Black Sea , from where they spread to other regions of Europe and Asia. Indo-European languages are the most common language family in the world today; the languages belonging to this group are spoken as mother tongues on all continents (except the uninhabited Antarctica ). There are only a few languages in Europe (e.g. Hungarian , Finnish , Estonian , Basque , Turkish ) that do not belong to this language family.

Classification of the Indo-European languages

The Indo-European language family consists of the following language groups or individual languages (some of them have already died out):

- Anatolian languages , for example Hittite (†). All languages of this group are extinct, they separated from the main proto-Indo-European trunk at a very early stage, probably no later than the 4th millennium BC;

-

Indo-Iranian languages with two subgroups:

- Indo-Aryan languages with many individual languages spoken on most of the territory of the Indian subcontinent (but not in its southern part), for example Hindi , Urdu , Bengali ;

- Iranian languages that are mainly spoken on the territory of Iran , Afghanistan , Pakistan , Tajikistan (for example Persian , Pashto );

- Balkan Indo-European languages , especially: Greek , Armenian and the extinct Phrygian . It is unclear or controversial whether Albanian , Illyrian (†) and Thracian (†) also belong to this subgroup. The Balkan Indo-European group is the closest related group to the Indo-European language family within Indo-European. Both groups together are also referred to as Eastern Indo-European ("Graeco-Aryan" in English);

- Slavic languages such as Russian , Polish, and Czech ; the closest related group is formed by the

- Baltic languages , of which only the two East Baltic languages Lithuanian and Latvian have survived to this day; In the 17th century, on the other hand, the (West Baltic) Old Prussian , which is of particular importance for the reconstruction of Indo-European because of its originality, died out;

- Italian languages , from which Latin and all Romance languages (such as Italian , French and Spanish ) are derived; the closest related group of Italian is formed by the

- Celtic languages , once a very common language group in Europe, today limited to small language communities in Great Britain ( e.g. Welsh , Scottish Gaelic ), Ireland ( Irish ) and France ( Breton );

-

Germanic languages with the following subgroups:

- North Germanic languages : Danish , Faroese , Icelandic , Norwegian and Swedish ;

- East Germanic languages : Burgundian (†), Gothic (†), Crimean Gothic (†), Suebian (Suevian) (†), Vandalic (Vandalic) (†) - all languages of this subgroup have already died out, the only one that has survived on the basis of preserved texts Language is Gothic;

- West Germanic languages : German , English , Dutch , Afrikaans , Yiddish and Frisian .

Italic, Celtic and Germanic together form the western group of Indo-European, to which the Baltic language group is often included. Within this western group, the forerunner of the later Germanic (the so-called Pre - Germanic language) in northern Central Europe separated from the Italo-Celtic group in southern Central Europe. This probably happened (at the latest) in the early 2nd millennium BC.

- Individual languages that have so far not been assigned to any of the above groups and are predominantly extinct (†), such as: Etruscan (†), Tochar (†), Venetian (†), Illyrian (†), Thracian (†) and also Albanian . The last three languages mentioned belong most closely to the Balkan Indo-European languages, while the Venetian is probably close to the Italian or Italo-Celtic .

Many similarities, both in vocabulary and in grammatical structures, testify to the relationship between all these languages, which seem to have little in common. The following table can serve as an example of this relationship, in which numerals from 1 to 10 as well as 20 and 100 in different languages and in their root - the Indo-European language - are shown:

| German | Greek | Vedic | Kurdish | Latin | Welsh | Gothic | Lithuanian | Serbian | Indo-European |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| one | heīs (< * hens < * sems ) | eka | yak | ūnus (see also semel ) | U.N | ains | vienas | jedan | * oyno-, oyko-, sem- |

| two | duo | dvā | you | duo | last | twai | you | dva | * duwóh₁ |

| three | treīs | trayas | Se | trēs | tri | þreis | trys | tri | * tréyes |

| four | téttares | catvāras | cwar | quattuor | pedwar | fidwor | keturi | četiri | * kʷetwóres |

| five | pénte | pañca | penc | quinque | pump | fimf | penki | pet | * pénkʷe |

| six | héks | ṣāt | seṣ | sex | change | saihs | šeši | šest | * swék̑s |

| seven | heptá | sapta | havt | septem | saith | sibun | septyni | sedam | * septḿ̥ |

| eight | octo | aṣṭā | have | octo | wyth | ahtau | aštuoni | osam | * ok̑tō |

| nine | ennéa | nava | no | novem | naw | niun | devyni | devet | * néwn |

| ten | déka | the A | there | decem | deg | taihun | dešimt | deset | * dék̑m̥ |

| twenty | wikati ( Doric ) | vimśati | bist / vist | viginti | ugeint (Middle Welsh ) | dvidešimt | dvadeset | * wīk̑mtī | |

| hundred | hekatón | śatam | sat | centum | cant | dog | šimtas | sto | * k̑m̥tóm |

The words marked with an asterisk (*) are reconstructed. No Indo-European texts have survived, and Indo-European words and sounds can only be inferred by systematically comparing the lexemes and phonemes. As linguistics advances in knowledge, these reconstructed forms have to be revised from time to time; Even according to the current state of research, Indo-European still remains a hypothetical construct fraught with uncertainty, the actual existence of which, however, is no longer questioned by any linguist. Despite all the uncertainties, linguists have tried not only to write individual words and forms, but also shorter texts (even an Indo-European fable , see below) in this language. It is evident that such reconstructions cannot reflect the changes that Indo-European has undergone in its history, as well as the variety of dialects spoken in different areas of this language.

Divergence of the Indo-European languages, eastern and western group

Through linguistic research, the vocabulary and grammatical structures of Indo-European can be traced back to the 4th millennium BC. To be developed; Only a few statements are possible about the genesis and earlier stages of development of Indo-European, for example with the linguistic method of so-called internal reconstruction. The process of differentiation of Indo-European began very early - probably no later than the 3rd millennium BC - the pre-forms of today's language groups began to develop from Proto-Indo-European, although it is not always certain in which order the subgroups and individual follow-up languages are separated.

Most likely today there is a primary breakdown into an eastern group (Indo-Iranian and Balkan Indo-European) and a western, "old European" group. The breakdown can hardly be traced back to about 3400 BC. Because both subgroups have common words for “hub” and “wheel” (for “wheel” there are even two different lexemes), but the invention of the wheel can be traced back to around 3400 BC by archaeological means. To date. The eastern group includes Sanskrit , Avestian , Greek and Armenian as the successor languages , while the western group includes the Baltic , Italian and Celtic languages and the Germanic language family. The proof of the primary subdivision of Proto-Indo-European into an Eastern and a Western group succeeded with the proof of a primary relationship between Greek and Sanskrit, in particular on the basis of common archaisms in the noun inflection of both languages (source: Wolfram Euler (1979)).

Until the discovery of Tocharian in the early 20th century, on the other hand, according to a theory by Peter von Bradke (1853–1897) from 1890, it was often assumed that the primary breakdown of Indo-European was that of the Kentum and Satem languages . The names come from the old Persian (satem) and Latin ( centum , pronounced kentum in the classical pronunciation of Latin ) word for hundred , which in Indo-European was * k̑m Indtóm . In the Satemsprachen (which mainly Slavic, Baltic and Indo-Iranian languages belong), the palatovelare * k gradually to a sibilant / s / and / ʃ / , as in satəm in Avestan (Old Persian) or sto in Polish . Romance and Germanic languages (including German), but also the Greek are against centum where the palatovelare * K and the velar k to palatal k (now h : hundred , Eng. Hundred ) coincide. The Indo-Europeanists in the 19th century were of the opinion that all the (original) Satem languages are in the east and all Centum languages in the west, but this contradicted the discovery of the extinct Tocharian (a Centum language, once spoken in today's Xinjiang region in China!) And Hittite in Asia Minor at the beginning of the 20th century. But this is not the only reason why this theory is now considered refuted. One of the other points of criticism right from the start was that there was a later (secondary) palatalization, i.e. H. Satemization existed. The pronunciation of the Latin “centum” changed from / k- / to / ts- / as early as the 2nd century AD. In Italian it became “cento” (spoken / ch- /), in French “cent” (spoken / s- /). As far as we know today, such “secondary satemizations” also existed in Slavic and Baltic. For a long time, the terms “Kentum and Satem languages” have only been used descriptively (descriptively) in the scientific field, but not in the sense of a linguistic-historical breakdown along this characteristic.

Text sample

As I said, no texts or inscriptions in Proto-Indo-European language have come down to us; the script didn't even exist at this point. Nevertheless, linguists have largely reconstructed the vocabulary (lexicon), the sounds (phonemes) and grammatical structures (morphology and syntax) of Indo-European, and they occasionally try to write short texts in this language. The best known of these is the so-called Indo-European fable The Sheep and the Horses , which was first written in 1868 by August Schleicher . After that, newer versions appeared several times, the changes of which document the progress of knowledge. The original version of Schleicher's fable follows. Schleicher's text is based on the assumption that Proto-Indo-European can be reconstructed primarily on the basis of Sanskrit and Avestan; he underestimated the importance of the Germanic languages and Latin for the reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European.

| Indo-European (Avis akvāsas ka) | German translation ( The sheep and the horses ) |

|---|---|

| Avis, jasmin varnā na ā ast, dadarka akvams, tam, vāgham garum vaghantam, tam, bhāram magham, tam, manum āku bharantam. Avis akvabhjams ā vavakat: kard aghnutai mai vidanti manum akvams agantam. Akvāsas ā vavakant: krudhi avai, kard aghnutai vividvant-svas: manus patis varnām avisāms karnauti svabhjam gharmam vastram avibhjams ka varnā na asti. Tat kukruvants avis agram ā bhugat. | A sheep that was out of wool saw horses, one driving a heavy wagon, one carrying a heavy load, one carrying a person quickly. The sheep said: My heart becomes narrow when I see that man drives horses. The horses said: Hear sheep, our hearts become narrow because we have seen: Man, the Lord, makes the wool of the sheep into a warm dress for himself and the sheep have no more wool. When it heard this, the sheep turned into the field. |

There are also translations of this fable into the ancient Germanic language, for example by the linguists Carlos Quiles Casas (2007) and Wolfram Euler (2009). Below is the version from Euler:

Awiz eχwôz-uχe. Awis, þazmai wullô ne wase, eχwanz gasáχwe, ainan kurun waganan wegandun, anþeran mekelôn burþînun, þridjanôn gumanun berandun. Awiz eχwamiz kwaþe: "Χertôn gaángwjedai mez seχwandi eχwanz gumanun akandun." Eχwôz kwêdund: "Gaχáusî, awi, χertôn gaángwjedai unsez seχwandumiz: gumô, faullôzranj sô garezn warmanô westranj sô avimiz wullô ne esti. ”Þat gaχáusijandz awiz akran þlauχe. (Source: Euler (2009), p. 213)

Urgermanic

Origin of the Teutons

The theory goes back to the physician Ludwig Wilser that the original home of the original Germans was in what is now Denmark and the adjacent parts of southern Sweden and northern Germany. Wilser advocated this theory from 1885, before a central European original home of the ancestors of the Germanic peoples was assumed. Wilson's theory was adopted from around 1895 by the prominent prehistorian Gustaf Kossinna and then prevailed, but it is still controversial today. The tribes, whose descendants later became known as Teutons, were probably not autochthonous inhabitants of these areas; they had immigrated there from other parts of Eurasia and possibly mixed with pre-Germanic inhabitants of these areas (a larger part - in former times one meant a third - of the Germanic vocabulary has no Indo-European roots). It is not known exactly how long the Germans lived in those territories; It is generally assumed that the beginnings of pre-Germanic culture and language up to the 2nd millennium BC. Go back BC.

The ancestors of the later Italians originally lived in the 2nd millennium BC to the south-east of these pre-Germanic areas, probably in Bohemia and areas bordering it to the east and south . On the other hand, Celtic tribes or their ancestors lived directly south and southwest of the Germanic area . Linguists found some similarities in the vocabulary between Germanic languages and Latin, which may indicate contacts and neighborhood relationships between these peoples. The word Hals (which had the same form in Old High German and Gothic: hals ) corresponds to the Latin collus ; the old high German wat ( ford , cf. wading ) the Latin vadum .

Towards the end of the 2nd millennium BC The Preitalians moved south and settled in what is now Italy , where parts of them later founded the city of Rome and the Roman Empire . The once pre-Italian areas were not settled by Germanic tribes until the 1st century BC. The spread of the Germanic tribes in Central Europe in the 1st millennium BC, however, happened predominantly at the expense of previously Celtic areas. This applies above all to the areas between the Ems and the Rhine and to the expansion south to the Main and further to the Danube. Presumably during the La Tène period, the contacts with the Celts, which had always existed, became more intensive, although at that time the Celts were culturally and probably also militarily superior to their northern neighbors. Contacts with Celtic tribes during this time led to the inclusion of many new words in the ancient Germanic language, for example in the field of politics (the word "Reich"), society (the word "Amt"), technology (the word "Eisen") , clothing (the word English "breeches" = pants.) and law (see altirisches. OETH , altsächsisches Ath and Old High german eid - Eid , or altirisches licud , gothic leihwan and Old High german lihan - borrow ).

Other neighbors of the Teutons in the east were the Venetians (some of whom, according to ancient writers, lived on the central Vistula) and the Illyrians . From the first, the Germanic peoples took over the term themselves (Venetian sselb- , compare Gothic silba , English self , Old High German selb ), from the others the word (bird) farmer comes from ( byrion was an Illyrian term for dwelling).

The result of the contacts of the Teutons with Slavic and Baltic tribes who lived east of their territories, however, are words like gold (Germanic ghḷtóm , cf. Polish złoto , Czech zlato ), thousand (Gothic tausūsundi , cf. Polish tysiąc , Lithuanian tukstantis ).

Origin of the Germanic language, first sound shift

The Germanic language evolved from Indo-European in the course of a slow process that began in the first half of the 2nd millennium and lasted for one to two millennia. The changes that led to the emergence of the original Germanic mainly concerned the phonology , for example accent ratios . While the Germanic accent, as in other Indo-European language branches, could initially be on different syllables - which also denoted differences in meaning - the dynamic accent on the stem syllable later prevailed. Mostly this was the first syllable of a word, but there are also unstressed prefixes. This form of word accent is still valid today in German and in the other living Germanic languages. In some languages (for example Russian ) the accent (as in Indo-European) remained flexible, i.e. that is, it can fall on different syllables of morphological forms of a word, the same was true for Latin and Greek.

This implementation of the initial stress gradually led to the weakening of syllables without an accent and brought about profound changes in the sound system, of which the so-called first sound shift had the greatest consequences for the later development of Germanic languages. The processes of the first phonetic shift, also known as the Germanic phonetic shift or Grimm's law, began around 500 BC at the earliest. At the birth of Christ they were complete. They included three changes in the consonant system:

- Indo-European voiceless plosives ( p , t , k , kʷ ) became voiceless fricatives ( f , þ , h , hw ).

- Indo-European voiced stops ( b , d , g , gʷ ) became unvoiced stops ( p , t , k , kʷ) .

- Indo-European aspirated stops ( bʰ , dʰ , gʰ , gʷʰ ) became voiced fricatives and then voiced stops ( b , d , g , gw , then w ).

The consequences of the Germanic phonetic shift in today's German are not always visible, because they were partially hidden by the later processes of the second phonetic shift (which led to the emergence of Old High German). The following table is intended to give an overview of the changes in the context of the first sound shift:

| Change | non-Germanic / unshifted ex. | Germanic / postponed ex. |

|---|---|---|

| * p → f | 1) Old Gr .: πούς (pūs), Lat .: pēs, pedis, Sanskrit : pāda , Russian .: под ( pod ), Lit .: pėda ;

2) Latin: piscis |

1) Engl .: foot, German: Fuß, Got .: fōtus, Isländ., Faroese: fótur, Danish .: fod, Norw., Swedish .: fot ;

2) Engl .: fish, German: fish, |

| * t → þ | Old Gr .: τρίτος (tritos), Lat .: tertius , Gaelic treas , Irish: tríú , Sanskrit: treta , Russian: третий ( tretij ), Lithuanian: trečias | English: third, Althdt .: thritto, Gothic: þridja, Isländ .: þriðji |

| * k → χ (χ became h) | 1) Old Gr .: κύων (kýōn), Lat .: canis , Gaelic, Irish: cú ;

2) Latin: capio ; 3) Latin: corde |

1) Engl .: hound, Dutch: hond, German: dog, Gothic: hunds, Icelandic, Faroese: hundur, Danish, Norw., Swedish: hund ;

2) Got .: hafjan ; 3) Engl .: heart |

| * kʷ → hw | Lat .: quod , Gaelic: ciod , Irish: cad , Sanskrit: ka-, kiṃ , Russian: ко- ( ko- ), Lithuanian: ką | Engl .: what, Gothic: ƕa ("hwa"), Danish hvad, Icelandic: hvað , Faroese hvat , Norw .: hva |

| * b → p | 1) Latin: verber ;

2) Lit .: dubùs |

Engl .: warp ; Sweden: värpa ; Dutch: werpen ; Icelandic, Faroese: varpa , Gothic wairpan ; Got .: diups |

| * d → t | Lat .: decem , Greek: δέκα ( déka ), Gaelic, Irish: deich , Sanskrit: daśan , Russian : десять ( des'at ), Lithuanian: dešimt ; | Engl .: ten, Dutch: tien, Gothic: taíhun, Icelandic: tíu, Faroese: tíggju, Danish, Norw .: ti, Swedish: tio |

| * g → k | 1) Latin: gelū ;

2) Latin: augeo |

1) Engl .: cold, Dutch: koud, German: cold, Isländ., Faroese: kaldur, Danish: kold, Norw .: kald, Schw .: kall ;

2) Got .: aukan |

| * gʷ → kw | Lithuanian: gyvas | Engl .: quick, Frisian: quick, queck , Dutch: kwiek, Gothic: qius, Old Norw . : kvikr, Norw. kvikk Iceland., Faroese: kvikur, Swedish: kvick |

| * bʰ → b | Lat .: frāter, old Gr .: φρατήρ (phrātēr), Sanskrit: (bhrātā) , Russian : брат ( brat ), Lithuanian: brolis , Old Church Slav .: братръ (bratru) | Engl .: brother, Dutch: broeder, German: brother, Gothic: broþar, Isländ., Faroese: bróðir, Dän., Swedish: broder, Norw. bror |

| * dʰ → d | Irish: doras , Sanskrit: dwār , Russian : дверь ( dver ), Lithuanian: durys | Engl .: door, Frisian: doar, Dutch: deur, Gothic: daúr, Icelandic, Faroese: dyr, Danish, Norw .: dør, Swedish: dörr |

| * gʰ → g | 1) Latin: hostis ;

2) Russian : гусь ( gus ) |

1) Got .: gasts ;

2) Engl .: goose, Frisian: goes, Dutch: gans, German: Gans, Isländ .: gæs, Faroese: gás, Danish, Norw., Swedish: gås |

| * gʷʰ → gw → w | 1) Sanskrit: gʰarmá

2) [Tocharian] A: kip , B: kwípe ( vulva ) |

1) Got .: warm

2) Engl .: wife, Proto-Germanic: wiban (from the previous gwiban ), Old Saxon, Old Frisian: wif, Dutch: wijf, Old High German: wib, German: Weib, Old Norw .: vif, Iceland .: víf, Faroese: vív, Danish, Swedish, Norw .: viv |

The real relationships in these changes, however, were more complicated than the table above shows, and were characterized by many exceptions. The best known of these exceptions is the so-called Verner's Law , which shows that the first sound shift must have taken place when the accent was still freely movable. If the accent fell on a syllable that followed the unvoiced plosives p , t , k , kʷ , they did not change to the voiceless fricatives f , þ , h , hw (as shown above), but to voiced ƀ , đ , ǥ , ǥʷ . Examples are shown in the following table, where Greek words (in which the Indo-European sounds have not been shifted) are compared to Gothic words:

| Change | Greek / unshifted ex. | Germanic (Gothic) / postponed ex. |

|---|---|---|

| * p → ƀ | έπτά | sibun ( seven ) |

| * t → đ | πατήρ | fadar ( father ) |

| * k → ǥ | δεχάς | -tigjus ( tens ) |

In addition to these differences in phonology , there were also changes in Germanic in other parts of the language system, especially in the use of verbs. In Indo-European the aspect first played an important role. This verbal category, which can appear as an imperfect or perfect aspect (cf. I sang a song and I was singing a song in English, both sentences are translated the same way into today's German: “I sang a song”), began as a language category to disappear in Germanic; Differences in form that related to the aspect gradually became verb forms that represented temporal differences (present and past tense).

Another important change in the morphological system was the emergence of the weak verbs that now form the past tense with -te (cf. the modern forms “I made”, “I worked” in contrast to the strong verbs “I went”, “I came").

Migrations of Germanic tribes

When discussing the language rules of Germanic, one has to keep in mind that the primitive Germanic language did not represent a uniform system from the very beginning. There was no Germanic language with fixed rules like today's German; the tribes of the Germanic peoples spoke their tribal languages.

This differentiation deepened when Germanic tribes began to migrate to other areas in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, before the actual migration of peoples , which only began later in Europe with the invasion of the Huns at the end of the 4th century . In the 3rd century the Burgundians moved from their residences on the Vistula and Oder to the Rhine, and later Slavic tribes took their place. Even earlier, namely in the 2nd century, the Goths began to migrate south, which is why they had no influence on the later development of the German. In the north, the Angles and Saxons migrated to Great Britain in the 5th century ; with their tribal languages they contributed to the emergence of the English language.

Of the many tribal languages of the Teutons, it was the pre-High German dialects of the Alemanni , Bajuwaren , Franconians and Thuringians as well as the North Sea Germanic dialects of the Saxons and Frisians , which became the basis of the German dialects ( dialect continuum ) up to today's standard German .

Influence of Latin on Germanic languages

Many Latin words were adopted into the Germanic languages through contacts between the Teutons and the Romans who advanced across the Rhine and Danube, fought wars with Germanic tribes and influenced the areas bordering the Roman Empire with their culture. For example, words from the areas of religion (such as sacrifice , cf. Latin offerre , Old Saxon offrōn ) and trade (for example, buy , cf. Latin caupo - innkeeper , cauponāri - haggle , Gothic kaupōn ; pound , cf. lat.. pondo ; coin , cf. lat.. Moneta , Norse mynt , altsächsisches munita ). Latin also gave names to new trade goods ( pepper , cf. Latin pīper ; wine , cf. vīnum ), new terms from the building industry ( wall , cf. Latin mūrus ; bricks , cf. Latin tēgula , old Saxon tiagla ), Horticulture ( cabbage , cf. Latin caulis , old Norse kāl ; pumpkin , cf. Latin curcurbita ), viticulture ( chalice , cf. Latin calix , old Saxon kelik ; wine press , cf. Latin calcatūra ), kitchen ( kettle , cf. Latin catinus , Anglo-Saxon cytel , Anglo-Saxon ketil ; and the word kitchen itself, cf. Latin coquina , Anglo-Saxon cycene ).

Wars between Romans and Teutons, but above all the fact that many Teutons served as soldiers in the Roman army, led to the adoption of many words from this area. Thus, from the Latin word pīlum (which in this language meant throwing spear ) developed over the Old Saxon and Anglo-Saxon pīl the current word arrow ; from the Latin pālus ( palisade ) the current stake arose (in Anglo-Saxon, Old Frisian and Old Saxon the word was pāl ).

In the 3rd to 5th centuries, the Teutons, under Roman and Greek influence, also took over the seven-day week, which is actually of oriental origin. The Germanic names of the days of the week were mostly loan translations of the Latin names, which came from the names of the planetary gods. Today's German weekdays have the following etymology :

- Sunday is the literal translation of the Latin diēs Sōlis ( day of the sun ), cf. Old Norse sunnu (n) dagr , Old Saxon sunnundag , Anglo-Saxon sunnandæg .

- Monday was translated in the same way from Latin diēs Lūnae ( day of the moon ), cf. Old Norse mānadadagr , Anglo-Saxon mōn (an) dæg , Old Frisian mōnendei .

- Tuesday , Middle Low German dingesdach , is a loan transfer from Latin diēs Mārtis ( day of Mars ) and goes back to the Germanic god Tyr , protector of the thing , with the Latinized name Mars Thingsus , cf. Old Norse tysdagr .

- Thursday arose from the Latin diēs Jovis by equating the Roman god Jupiter with the Germanic god Donar , cf. Old Norse þōrsdagr , Anglo-Saxon þunresdæg , Old Frisian thunresdei .

- Friday (Latin diēs Veneris ) came into being in a similar way - the Germanic goddess Fria was identified with the Roman goddess Venus .

- Wednesday seems to be an exception here, but it also has something in common with the Latin language and Germanic mythology. The word is a loan translation from kirchenlat. media hebodamas and only prevailed in Late High German ( mittawehha ). The day used to be called Wodanstag (English "wednesday" or Dutch "woensdag").

- Saturday is the only word here that comes from the Greek ( sábbaton ) and, indirectly, Hebrew Shabbat ( שבת) was borrowed.

Runic script

We already have written records from the era of the Germanic language, although they are still very rare and usually only consist of short inscriptions on objects. They were mainly written in the runic script, which was used by the Teutons from the 2nd to the 12th centuries (as a result of the Christianization of Germanic areas, it was later replaced by the Latin script). It is usually assumed that the runic writing developed around the turn of the ages from the letters of the North Etruscan alphabet , which was also briefly used by the Teutons. This is particularly evidenced by the inscription on a helmet that was found in Negau (today Negova in Slovenia ) in 1811 - the possibly Germanic text was written using letters from the North Etruscan alphabet, from which the runes are said to have emerged.

Text sample

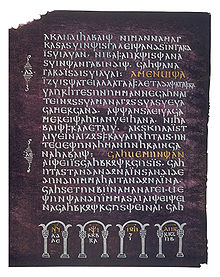

Apart from fragmentary runic inscriptions, only one major work survived before the 8th century AD, which was written in one of the Germanic languages, namely the Gothic translation of the Holy Scriptures from the late 4th century. Of this so-called Wulfilabibel , only a little more than half of the New Testament and a small fragment of the Old Testament (prophet Nehemia), by no means the entire text of the Bible, have been preserved. It should also be noted that the German language in no way goes back to Gothic, a form of East Germanic. Rather, the Gothic language developed away from the other Germanic dialects as early as the 2nd century BC. The text of the prayer Our Father from the Gospel of Matthew follows (Mt 6, 9-13):

| Gothic (Wulfilabibel) | Modern German (current ecumenical version) |

|---|---|

|

|

This text was also translated into the ancient Germanic language by linguists. This is relatively safe because the text is not only available in a Gothic version but also in Old High German, Old English and Old Icelandic :

Fađer our ini χiminai, weiχnaid namôn þînan, kwemaid rîkjan þînan, werþaid weljô þînaz χwê ini χiminai swê anâ erþâi, χlaiban unsan, in sénteinan give unsiz χija atulan fl ê ake lausî unsiz afa ubelai. þînan esti rîkjan, maχtiz, wuþus-uχ ini aiwans. (Source: Wikipedia article Language comparison based on the Our Father , or Euler (2009), p. 214).

Old High German

Analogous to the difficulties with the chronology of the ancient Germanic, the exact dating of the old high German language, especially with regard to its origin, is hardly possible. Linguists only generally assume that the processes that led to the development of Old High German began around AD 600 with the second sound shift. The period of Old High German in the history of the German language lasted until around 1050.

Formation of Germanic states and the East Frankish-German Empire

The 5th century was the time of great turbulence in European history. As a result of the migrations, which became known as the Great Migration , the Roman Empire finally collapsed, and its place was often replaced by rather short-lived tribal states of the Germanic peoples , such as the Empire of the Ostrogoths in Italy or the Empire of the Visigoths in Spain. The most powerful of these states was the Franconian Empire of the Merovingians , founded by Clovis I in 482 , which subjugated several other Germanic tribes (e.g. Alemanni, Thuringians, Burgundians) in the following centuries. The Merovingians were followed in the 8th century by the Carolingians , who under Charlemagne expanded their empire to the Elbe and Saale in the east, the Ebro in the west and to Rome in the south. On the basis of the Treaty of Verdun in 843 the Franconian Empire split into three parts, and the eastern part became the cradle of the modern German nation. The first East Frankish king was Ludwig the German (843–876); Heinrich von Sachsen came to power in Eastern Franconia in 919 as the hour of birth of the German nation .

Christianization. Spiritual and cultural life in the early Middle Ages

After the chaos that accompanied the collapse of the Roman Empire, the rebuilding of cultural life began only slowly, particularly through the Christianization of Germanic tribes who worshiped even older deities. In today's southern Germany and Switzerland, the Christianization of the Alemanni began by Irish monks in the 6th and 7th centuries. As a result of their efforts, the St. Gallen Monastery was established in 614 and then (724) the Reichenau Monastery . In the north of Germany, Saint Boniface in particular made efforts to Christianize. The monasteries that the missionaries founded were very important centers of radiation not only of the Christian faith, but also of culture. The language of the church services was still Latin, but the monks and the rulers also used the vernacular - they would not have been able to bring new Christian ideas closer to the rural population in Latin. In 789, Charlemagne ordered the use of the vernacular in pastoral care and sermons in the Admonitio Generalis chapter, and at the Synod of Frankfurt in 794 the vernacular was given the same status as Hebrew, Latin and Greek.

Divergence of the Germanic languages

These efforts by the rulers and clergy resulted in the popular language, including its written forms, becoming increasingly important. Contacts between different tribes and the fact that they lived in one state meant that local tribal languages began to be replaced by territorial dialects. The tribes whose languages played the most important role in the development of these territorial dialects were the Alemanni, Bavaria, Franconia, Thuringia and Saxony. The development of poetry caused the dialects to develop their literary variants as well.

However, these processes of rapprochement between the languages of individual tribes could not prevent the languages of more distant tribes from starting to diverge. What is meant here are above all the differences between Eastern Franconia, with a predominantly Germanic population, and Western Franconia, whose inhabitants were strongly Romanized. As early as the 9th century, the linguistic differences among the inhabitants of both empires were so great that in the Strasbourg oath in 842, when Charles the Bald from the western empire and Ludwig the German from the eastern empire pledged to provide mutual support against their brother Lothar , each had to swear in his own language in order to be understood by their armies. The dialects that were spoken in the two halves of the empire later developed into today's German and Dutch on the one hand and French on the other; Eastern and Western France later became Germany and France.

Development of literature

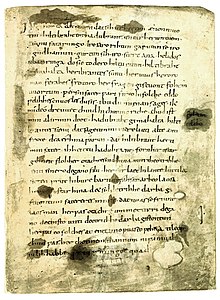

We owe the oldest works in Old High German that have survived to this day to monks in monasteries who recorded and preserved them. Interestingly, it was not only religious literature, but also secular works, such as the Hildebrandslied , which originated in the 7th century and was written down in the Fulda monastery around 830 . The first glossaries - Latin-German dictionaries - of which Abrogans , which was created around 765 in the cathedral school in Freising , is the best known.

Examples of religious literature from this period include the Wessobrunn prayer or Muspilli - a poetry of the end of the world from the 9th century. The Bible and its fragments were of course also translated or revised, for example the Gospel Harmony by the Syrian Tatian . A particularly interesting example of this literature is the Old Saxon epic Heliand , in which Jesus shows characteristics of a Germanic ruler.

Origin of Old High German. Second sound shift

The turning point that led to the emergence of Old High German is a sound change in the area of consonantism , which is known as the second sound shift . (The earlier first phonetic shift mentioned earlier caused the separation of the original Germanic from the Indo-European.) In the second phonetic shift of the 7th century, changes were made to the Germanic plosives p , t , k , which in Old High German, depending on their position in the word, to the sibilants f , s , h , or affricates pf , ts , kh . Another group of sounds that was subject to change were the Germanic fricatives ƀ / b , đ / d , ǥ / g , þ , which became the Old High German plosives p , t , k , d . The following table contains an overview of these changes that led to the development of Old High German. For greater clarity, the changes in the first sound shift have also been taken into account in the table. (The letter G (Grimm's law) means that normal rules worked for the first phonetic shift; the letter V (Verner's law) indicates exceptions that can be traced back to Verner's law. This explanation only applies to the first, not the second phonetic shift .)

| First sound shift (Indo-European → Germanic) |

phase | High German sound shift (Germanic → Old High German) |

Position in the word | Examples (New High German) | century | Geographical expansion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G: / * b / → / * p / | 1 | / * p / → / f / | 1. In the intro between vowels . 2. Final after vowel. |

1. Low German: sla p en, English: slee p → sleep f en; 2. Low German and English: Schi pp , shi p → Schi ff . |

4/5 | South and Central Germany |

| 2 | / * p / → / pf / | 1. Initially . 2. In the initial and final after l , r , m , n . 3. In doubling. |

1. Low German: P eper, English: p epper → Pf effer; Low German: P lauch, English: p lough → Pf lug; 2. Gothic: hil p an, English: hel p → Old High German hel pf an → hel f en; Low German: Scher p , English: Shar p → Old High German: Shar pf → Shar f . 3. Anglo-Saxon: æ pp el, English: a pp le → Old High German: a pf ul → A pf el. |

6/7 | Upper German language area | |

| G: / * d / → / * t / | 1 | / * t / → / s / | 1. In the intro between vowels. 2. Final after vowel. |

1. Low German: e t en; English: ea t → e ss en. 2. Low German: da t , wa t ; English: tha t , wha t → da s , wa s . |

4/5 | Upper and central German language area |

| 2 | / * t / → / ts / | 1. Initially. 2. In the initial and final after l , r , m , n . 3. In doubling. |

1. Low German: T iet, English: t ide (flood), Swedish: t id → Z eit. 2. Low German: comparable t ellen, English: t ell → ER- for Aehlen; Anglo-Saxon: swar t → Old High German: swar z → black z . 3. Anglo-Saxon: se tt ian → Old High German: se tz an → se tz en. |

5/6 | Upper and central German language area | |

| G: / * g / → / * k / | 1 | / * k / → / x / | 1. In the intro between vowels. 2. Final after vowel. |

1. Low German and English: ma k en, ma k e → ma ch en; 2. Low German: i k , Old English: i c → i ch ; Low German: au k → au ch . |

4/5 | Upper and central German language area |

| 2 | / * k / → / kx / | 1. Initially. 2. In the initial and final after l , r , m , n . 3. In doubling. |

1. K ind → Bavarian: Kch ind; 2. Old Saxon: wer k → Old High German: wer kch → Wer k . 3. Old Saxon: we kk ian → Old High German: we kch an → we ck en. |

7/8 | southeastern Austria-Bavaria and the highest Alemannic language area | |

| G: / * b ʰ / → / * b / V: / * p / → / * b /

|

3 | / * b / → / p / | B erg, b is → Bavarian: p erg, p is. | 8/9 | Partly Bavarian and Alemannic language areas | |

| G: / * d / → / * đ / → / * d / V: / * t / → / * đ / → / * d / |

3 | / * d ʰ / → / t / | Low German: D ag or D ach, English: d ay → T ag; Dutch: va d er → Va t er. |

8/9 | Upper German language area | |

| G: / * g ʰ / → / * g / V: / * k / → / * g /

|

3 | / * g / → / k / | G ott → Bavarian: K ott. | 8/9 | Partly Bavarian and Alemannic language areas | |

| G: / * t / → / þ / [ð] | 4th |

/ þ / → / d / / ð / → / d / |

English: th orn, th istle, th rough, bro th er → D orn, D istel, d urch, Bru d er. | 9/10 | All of Germany and the Netherlands |

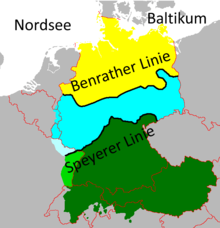

The processes shown in the table began in the Alpine region at the end of the 5th century and gradually spread north over three to four centuries. Only with the Alemanni and Bavaria were they fairly consistent, they only partially covered the areas inhabited by Franks, and in the north of German areas inhabited by the Saxons they left little or no traces. For this reason one speaks of the so-called Benrath Line , which today runs from Aachen via Düsseldorf , Elberfeld , Kassel , Aschersleben , Magdeburg to Frankfurt (Oder) . To the north of the line the processes of the second sound shift did not take place, or only to a small extent; the line thus represents the boundary between High German and Low German as well as Low Franconian .

Other changes in the phonological and morphological system

The second sound shift was the most important phenomenon that was important for the separation of Old High German from Germanic; In the second half of the first millennium, however, other interesting processes also took place in the language system.

The most important change in vowelism was the umlaut of the Germanic a to the Old High German closed e as a result of the effect of an i or j of the following syllable. As an example one can give here the singular-plural opposition of the word gast . While in Germanic the forms were still gast - gasti , in Old High German they changed to gast - gesti (this assimilation could, however, be prevented by certain consonant combinations, for example ht or hs ).

In Old High German, the forms of the definite and indefinite article appeared for the first time , which were still completely absent in Indo-European. The definite article developed from the demonstrative pronouns der , das , diu ; the indefinite from the numeral one . Both owe their existence to the dwindling number of cases and simplifying endings of nouns . The meaning and relationships of a noun to other words in the sentence in Old High German could no longer be recognized as easily as was the case in Indo-European because of the endings.

For similar reasons, personal pronouns began to be used more often in sentences. In the past they were not necessary in Germanic (as in Latin), because the person could be recognized by the personal ending. While the first words of the Christian creed in the St. Gallen version from the 8th century are still kilaubu in kot fater almahtîcun , in the Notker version from the 10th century we already read : I keloubo in got, almahtigen fater .

There were also important changes in the tense system. While there were only two tenses in Germanic - the past tense and the present tense - new, analytical tenses began to develop in Old High German, in which the time relationships are expressed with a main verb and an auxiliary verb . So we already find in Old High German texts examples of the perfect tense ( I have iz Funtan , now he is queman ), the future tense ( nû willu ih Scriban - I will write , see. I want in English), the Plusquamperfekts and the passive voice ( iz what ginoman ).

In the word formation a new suffix - -āri appeared, which was borrowed from the Latin -ārius and in Middle High German took the form -er . The suffix was initially limited to words of Latin origin (for example mulināri from Latin molinārius 'Müller'), later it was also extended to native words.

Influence of the Latin language

The influences of the Latin and partly Greek language, which were still visible in Germanic languages, intensified with the Christianization of German areas. The new religion required the introduction of new terms that were previously foreign to the Germans. Many of these new words were loan formations , which were the copying of foreign words with the means of one's own language (when new words were coined , one had to know the structure and etymology of the foreign word). So from Latin com-mūnio the Old High German gi-meini-da or from Latin ex-surgere the Old High German ūf-stān ( resurrect ).

Most of these new formations, however, were loan meanings in which the meaning of a word from one's own language was adapted to a new term. A good example is the Old High German word suntea , which was first used in the secular sense and meant behavior that one is ashamed of. Christianization replaced this old meaning with a new one ( sin ).

After all, many words were taken directly from Latin into the German language, not only from the field of religion, such as klōstar ( monastery , Latin claustrum ), munich ( monk , Latin monachus ), but also from education: scrīban (to write , lat. scrībere ), scuola ( school , lat. scōla ), horticulture: petersilia (medieval Latin: pētrosilium ) or the healing arts: arzat (er) ( doctor , lat. from Greek: archiater ).

Many place names ending in -heim ( Pappenheim , Bischofsheim ) are probably also a loan translation to the Latin villa .

The word "German"

During the Old High German period, the word “German” appeared for the first time in its current meaning. The word is of Germanic origin; In Old High German, diot meant “people” and diutisc - “folk-like”, “belonging to one's own people”. The word was also taken over very early in Latin sources in the form theodiscus and was used to distinguish between Romanic and Germanic inhabitants of the Frankish Empire. An interesting example of its use can be found in the report of an imperial assembly of 788, where the Bavarian Duke Tassilo was sentenced to death. The clerk of the chancellery stated that this was because of a crime, quod theodisca lingua harisliz dicitur ("which is called harisliz [desertion] in the vernacular"). At first the word was used only in relation to language; in Notker von Sankt Gallen, for example, we find around 1000 in diutiscun - "in German". It wasn't until almost a century later, in the Annolied , which was written in the Siegburg monastery around 1090 , that we read of diutischi liuti , diutschi man or diutischemi lande .

Text samples

Much more texts have survived from the Old High German period than from ancient Germanic languages; Their spectrum ranges from pre-Christian, Germanic heroic songs to works influenced by the Christian religion. There are only a few examples of Old High German literature:

| Hildebrandslied (fragment in Old High German) | Modern translation |

|---|---|

|

|

| Merseburg magic spells (fragment in Old High German) | Modern translation |

|---|---|

|

|

| Petruslied (Old High German) | Modern translation |

|---|---|

|

|

Middle High German

The beginnings of the Middle High German language are dated to the year 1050; This development phase of the German language lasted until around 1350 and corresponds roughly to the period of the High Middle Ages in Medieval Studies . As with all linguistic phenomena, these time frames are only roughly given; the processes that led to the emergence of Middle High German and then its successor, Early New High German, took place at different speeds in different regions of the German-speaking area; As in the other epochs, the German language was also largely spatially differentiated.

In the political history of the German-speaking area, political fragmentation began around 1050; the rulers of individual territories made themselves more and more independent of the emperor, which ultimately led to the emperor's power being only illusory and the German empire becoming a conglomerate of practically independent states. Another factor that contributed to the differentiation of the German language was the Ostsiedlung, i.e. the settlement of the German-speaking population in the formerly Slavic and Baltic-speaking development areas and the assimilation of large parts of the population there.

Spiritual-cultural life

The intellectual and cultural life in high medieval Germany was not limited to one center, but concentrated at the courts of the emperor and individual rulers. The southern German (Bavarian, Austrian and Alemannic) area was of particular importance. In the sphere of influence of the Guelphs in Bavaria, poems such as the Alexanderlied by Pfaffen Lamprecht or the German translation of the Roland song by Pfaffen Konrad were created . German literature of the high Middle Ages reached its peak at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries at the court of the Hohenstaufen emperors and the Babenbergs in Vienna. Mostly based on the French model, epics such as Erec and Iwein by Hartmann von Aue , the Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach or the Tristan by Gottfried von Strasbourg were created here .

Literary work also developed in northern Germany - in the Lower Rhine-Maasland area and in Thuringia, where ministerials created who processed ancient materials. The most famous poet from this group is Heinrich von Veldeke , author of the Eneasromans ; The Liet von Troye by Herbort von Fritzlar and the translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses by Albrecht von Halberstadt were made in this area .

This development of literature in different centers in the German-speaking area also meant that we cannot speak of any uniform literary German language. There were several variants of literary language based on territorial dialects; the most important were the Bavarian variant, the West Central German-Maasland variant and the most important of them - the so-called Middle High German poetry language of the Alemannic-East Franconian area, which arose in the sphere of influence of the Hohenstaufen emperors. Hartmann von Aue, Wolfram von Eschenbach and the unknown author of the Nibelungenlied wrote their works in this language .

Changes in the phonological system

The changes in the phonological system of Middle High German compared to Old High German were not as drastic as they were in the case of Old High German compared to Original German - the Middle High German language is much closer to modern German, although Middle High German texts are difficult to understand when untranslated. Nevertheless, there were some important changes in the consonant and vowel systems in Middle High German:

- The most important change in the phonological system of Middle High German was the weakening of unstressed syllables. The reason for this change was the strong dynamic accent that fell on the stem syllable in Germanic and Old High German. This strong accent eventually caused to that vowels in unstressed final syllables for schwa vowel ( [ ə ] ), the e was written, developed. Thus the Old High German boto became the Middle High German messenger , and the Old High German hōran became the Middle High German hear .

- Another important phenomenon in vowelism was the umlaut , which began in Old High German, but only now came to full development, and now also included long vowels and diphthongs. So ahd. Sālida developed into mhd. Sælde , ahd. Kunni into mhd. Künne , ahd. Hōhiro into mhd. Higher , ahd. Gruozjan into mhd. Grüezen .

There were also important changes in consonantism :

- The consonants b , d , g and h began to disappear when they were between vowels. Thus developed ahd. Gitragidi to MHG. Cereal , OHG. Magadi to MHG. Meit , OHG. Have to MHG. Han . In some cases, however, the old forms prevailed again later (cf. Magd , haben ).

- The Old High German consonant z , which developed from the Germanic t (cf. ezzan - English eat ) coincided with the old consonant s , still derived from Germanic - ezzan became to eat .

- The Old High German sound connection sk became too sch . For example, from the Old High German word scōni the Middle High German schōne and schœne (both words - already and beautiful - have the same origin in today's German).

- The consonant s changed to sh when it came before l , m , n , w , p , t . It is to this change that we owe the Middle High German (and today's) forms such as swim , pain , snake , schnē , which arose from the Old High German swim , smerz , slange and snē . In the spelling, however, this change was not immediately visible: first, in Middle High German, for example, swimmen was written and swimming was spoken. In the case of the letter combinations st and sp , the difference between the pronunciation and spelling has remained to this day - cf. the pronunciation of the words stand , play .

Changes in the morphological and syntactic system

Changes in the morphological system of the Middle High German language were largely dependent on the phonological system. Of critical importance was the weakening of vowels in unstressed final syllables to here schwa vowel ( [ ə ] ). This change led to drastic changes in the declension of nouns - there was a formal correspondence between previously different case forms. As an example, you can give the declination of the Middle High German word bote (from the Old High German boto ):

| case | Old High German | Middle High German |

|---|---|---|

| Nominative singular | boto | delivery boy |

| Genitive singular | botin | offered |

| Dative singular | botin | offered |

| Accusative singular | botun | offered |

| Nominative plural | boton / botun | offered |

| Genitive plural | botōno | offered |

| Dative plural | botōm | offered |

| Accusative plural | boton / botun | offered |

This development gave the article (which already existed in Old High German) great importance (for example, the messenger , the messenger ) - without it the identification of the case would be impossible.

The weakening of the full vowels to the Schwa sound also resulted in changes in the system of conjugation of the weak verbs that form the past tense with the suffix -te (for example, I made , we answered ). In Old High German there were three subclasses of these verbs with the suffixes -jan (for example galaubjan ), -ôn ( salbôn ) and -ên ( sagên ). After the weakening, the verbs mentioned were: believe , anoint , say ; the old three suffixes merged into one -en .

In the case of the verb forms, there was a further differentiation of the tense system in Middle High German. Analytical tenses such as the perfect, past perfect and future (which already existed in Old High German) became more common. For example, we can read in the Nibelungenlied:

Swaz der Hiunen mâge / in the sale what was,

who enwas nu none / inne mê recovered.

The structure of the sentences was not yet too complicated, the syntax was still dominated by the principle of secondary order, which the next fragment from the Nibelungenlied shows:

Dō stuonden in den venstern / diu minneclīchen kint.

Ir ship with the sail / daz ruorte a higher wint.

The proud heroes / the sāzen ūf den Rīn.

Dō said the künec Gunther: / who should be a skipper?

Occasionally, however, extended structures ( sentence structure with subordinate clauses ) appear in Middle High German texts that already existed in the earlier period.

Changes in vocabulary. Foreign language borrowings

The German culture of the High Middle Ages was strongly influenced by French culture, which was reflected in the large number of borrowings from French. These loans often came to Germany via Flanders. We owe the French borrowings in Middle High German, for example, tournament (mhd. Turnei ), palace (mhd. Palas ), pillows .

Certain loan coins, which were modeled on this language, also come from French. These include, for example, the words Hövesch ( courtly ), which was formed from the old French courtois , and ritter (from the old French chevalier ).

Of French ancestry, there are also certain suffixes such as -ieren ( study , march ), which arose from the French -ier , and -ei , which developed from the Middle High German -īe (for example zouberīe - magic , erzenīe - medicine ).

Contacts of the Germans with their Slavic neighbors in the east also led to the adoption of certain words, although the number of these borrowings was much less than that of French. For example, border (mhd. Grenize , Polish. Granica ) and manure (mhd. Jûche , Polish. Jucha ) come from Slavic .

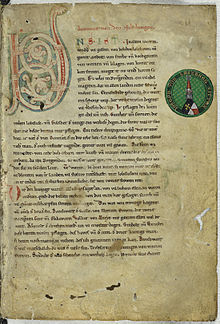

Text samples

Poor Heinrich von Hartmann von Aue

| Poor Heinrich (Middle High German) | Modern translation |

|---|---|

|

|

Tristan by Gottfried von Strasbourg (praise from Hartmann von Aue)

| Tristan (Middle High German) | Modern translation |

|---|---|

|

|

Nibelungenlied

| Nibelungenlied (Middle High German) | Modern translation |

|---|---|

|

|

Early New High German

According to popular belief, Martin Luther is the creator of the modern German language. Although his services to German culture are indisputable, the opinion still held by linguists in the 19th century that Luther's translation of the Bible was groundbreaking for the development of German does not agree with the results of modern research. The development of today's German began as early as 1350, when the early New High German language began to develop. The early New High German period in the development of the German language lasted until around 1650.

Political and economic prerequisites for the development of early New High German

In the late Middle Ages, the domestic politics of the German Empire continued to lead to the decentralization of the state and a weakening of imperial power. In 1356 the imperial law, which was Golden Bull of Charles IV. , Adopted in the political system was finally settled in Germany - the elective monarchy by the electors was manifested in writing. The empire was divided into a multitude of territories created, merged, or fragmented through inheritance and marriage. In 1442 the name Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation appeared for the first time.

Trade and manufacturing flourished in the late Middle Ages, especially in the north-west of the empire - in Flanders and Brabant , whose cities Bruges , Ghent and Antwerp had been leading economic centers since the middle of the 13th century. In the 15th century, Flemish cities lost their importance, and the focus of trade shifted to the north, where the Hanseatic League was the most important factor in the economic development and charisma of the Germans. Trade contacts that went well beyond the borders of local territories promoted the development of a unified, standardized language that was not tied to dialects.

The Imperial Chancellery also needed a common language to draft official documents. The imperial court in late medieval Germany changed its seat over time, which also influenced the development of the German language. Charles IV from the Luxembourg dynasty resided in Prague in the 14th century , which led to a strong proportion of Bavarian and East Franconian elements in the language used at his court. When the Habsburg dynasty came to power, the imperial chancellery was relocated to Vienna in the 15th century, and East German elements took precedence in the chancellery language. In the east of Germany (especially in today's Saxony and Thuringia ), on the other hand, the Wettins gained importance from the 15th century . This led to the fact that around 1500 two variants of the common language competed with each other in Germany: the East Central German variant of the Meissnian-Saxon chancellery ( Saxon chancellery language ) and the Upper German variant of the imperial chancellery ( Maximilian chancellery language , which later developed into the Upper German writing language), which developed based on different territorial dialects. These two variants, like the languages of the Flemish trading centers and the Hanseatic cities earlier, were not only used in the domain of the Wettins and Habsburgs, but also found recognition in other parts of the empire.

Spiritual and cultural development in the late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages were characterized by the development of science and education. Above all, the establishment of the first universities on German soil in the 14th century should be mentioned here. The first university within the imperial borders was the University of Prague , founded by Emperor Charles IV in 1348; it was followed by the University of Vienna (1365) and the University of Heidelberg (1386). Although the teaching at the universities was in Latin, the universities contributed to deepening the interest in general knowledge and thus the German language.

Culture and education were also promoted by the quickly enriching and emancipating middle class. The Meistersinger tradition dates from the 15th century , and around 1400 Johannes von Tepl's Der Ackermann von Böhmen was written , a work in which early humanist concepts can be found a hundred years before they were generally adopted in German culture.

The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1446 was of crucial importance for the development of culture and literature. This invention opened up completely new perspectives for the development of language - books were now cheaper and reached a much wider section of the population than before. The majority of the books printed in the early New High German period were still written in Latin (the number of German prints exceeded that of Latin for the first time in 1681), but the importance of the German language in publishing grew steadily, especially since the circulation of German books was usually larger than that the Latin goods. Folk books such as Till Eulenspiegel (1515) and Historia by D. Johann Fausten (1587) enjoyed great popularity . Luther's translation of the Bible had even larger editions, of which around 100,000 copies were printed between 1534 and 1584. Authors targeting readers nationwide with their books could not write in local dialects, but had to use a standard language that was understandable everywhere. At first there were several variants of this standard language, in which books were printed in different areas of the German-speaking area; in the 16th century they began to align.

Changes in the phonological system

The late Middle Ages were the last epoch in which important changes were made in the phonological system of the German language - it was precisely these changes that enabled the emergence of Early New High German from Middle High German. These changes have been implemented to varying degrees in different German dialects. In particular on the southwestern edge of the German-speaking area there are Alemannic dialects where none of these changes have found their way. The main changes were:

- Quantitative changes in the length of the vowels that began around 1200 in Low German and gradually expanded southwards:

- Short open vowels that were in a stressed position were stretched. For example, the Middle High German words lěben , gěben , trăgen , bŏte , lĭgen became early New High German lēben , gēben , trāgen , bōte , lī (e) gen , which pronunciation has been preserved to this day.

- Long vowels followed by several consonants, however, were shortened. From the Middle High German words dāhte , hērre , klāfter , for example, the early New High German forms dăchte , hěrr , klăfter .

- Qualitative changes in the main tone syllables that affected diphthongization and monophthongization:

- Stem syllable vowels ī , ū , iu became diphthongs ei , au , eu . For example, the Middle High German words wīse , mūs and triuwe developed into the early New High German forms wise , mouse and faithful , and for example people who moved into a new house did not say mīn niuwez hūs , but my new house . This change first appeared in the eastern Alps in the 12th century and spread to the northwest. The Low German and southwestern Alemannic area remained however unaffected, so one does not speak today in Switzerland Swiss German , but Schwizer Dütsch .

- After the diphthongization (in some regions of Central Hesse but before this; see Central Hessian dialects ), the monophthongation took place , a reverse process in which the diphthongs ie , uo , üe , which were in emphasized positions, became the long monophthongs ī , ū , ü developed. As a result of the process, the Middle High German words rent (in Middle High German the word [ˈmiə̯tə] was pronounced), bruoder and güete became early New High German mīte , brūder and güte ; and someone who had siblings could now call them not dear guote brothers but lībe gūte brothers . This innovation began in Central Hesse and spread to the Central German-speaking area. In Upper Germany, the diphthongs are still used today, while the Lower German region had never developed these diphthongs at all.

- Middle High German diphthongs ei , ou and öu (spoken öü ) have also changed, whereby it should be noted that the first letter combination in Middle High German was not pronounced ([ai]) as now, but [ei]. The diphthongs ei , ou and öu became ei [ ai ], au and eu [ oi ] in Early New High German ; so was stone [stone] stone , roup to robbery and fröude to joy . This process is called New High German diphthong reinforcement and took place in Central Germany; in Upper German (Bavarian and Alemannic), however, not.

Changes in the morphological and syntactic system

Changes in the morphological system of early New High German were not as drastic as in the phonology or morphology of earlier epochs.

Changes occurred mainly in the numerus , in which various means of marking the plural came into use. The umlaut gained greater importance and now appeared where it had no phonological justification. In the early New High German era, singular-plural oppositions such as hof / Höfe , stab / stebe , nagel / negele , son / sons emerged . The plural has now been formed more often with the help of the sound r , which was previously only used very rarely in the formation of the plural. While in Middle High German there were still the forms diu buoch , diu wort (without any suffix ), we already encounter the forms of the books and the words in early New High German texts .

New suffixes were characteristic of derivatives as well. In the early New High German period, the suffixes -heit , -nis and -unge appeared for the first time - the words formed with their help were often German translations of Latin abstract terms, for example hōhheit (lat. Altitudo ), wonder (lat. Miraculum ).

As prefixes were loading , corresponds , ER , comparable , decomposed , ABE , ANE , UF , renaming , UZ and domestic often used. New suffix and prefix formations occurred particularly in the mystical literature of this time, which was always looking for new means of expressing abstract terms and feelings. For example, in a mystical treatise from the late Middle Ages we read:

Dîn güete is an overflowing well; if he is a tûsintist part of a wîle sînen ûzfluz lieze, so ê himel under ertrîch must be destroyed.

The use of suffixes and prefixes also varied depending on the region of the writer or speaker. For example, while Luther in his writings the prefixes comparable , decomposed preferred (which later permeated) were in the Early New High German language, especially in its East Middle variant also proposed , to- ( zubrochen ) common. Of the suffixes of the German language, the Abstraktsuffix was, for example, particularly in the southern German variant -nus ( erkenntnus ) used while awaiting completion by the ostmitteldeutsche nis was ousted.

The syntactic structure of early New High German texts is characterized by greater complexity than in earlier epochs; the sentences became longer, with a greater proportion of the sentence structure. This tendency continued over the next centuries and in the written language, especially in the 17th century, finally led to the fact that literary and official texts in their complexity and baroque ornamentation were hardly manageable.

In Early New High German the modern word order of the German language was already recognizable - with the verb in the second position and the order of other parts of the sentence according to their importance in the sentence - the most important part of the sentence at the end.

Changes in vocabulary

Change of meaning

As in the other stages of German development, there was often a change in meaning in early New High German, which reflected changed social conditions. Here are just three examples of these changes:

- Woman - virgin - woman - maid : In Middle High German courtly poetry, the word vrouwe was only used for noble mistresses and wives of feudal lords (correspondingly juncvrouwe meant young noble ladies ). Normal names for women were wīp and (in relation to young girls) maget . In early New High German, the word wīp was perceived as a swear word, maget changed its meaning and now meant "maid", vrouwe became the neutral term, and in the word juncvrouwe , virginity and celibacy became the most important part of the meaning.

- Noble : In Middle High German, the word was neutral and only referred to aristocratic origin or things from the noble's sphere of life. Now the word has been used to describe spiritual and moral qualities.

- The word leie experienced a similar expansion of meaning . Since the early New High German period it has not only meant “non-clergy”, but also someone who has no specialist knowledge in a field (“laypeople”, for example, were educated citizens who did not owe their education to a university degree).

Introduction of family names

In the late Middle Ages (in the 13th and 14th centuries), fixed family names were finally introduced in the German-speaking area . Growing populations in cities meant that nicknames were no longer sufficient to identify the inhabitants. The family names very often came from professions ( Hofmeister , Schmidt , Müller ) but also from characteristics of the people ( Klein , Lang , Fröhlich ), their origins ( Beier , Böhme , Schweizer ) or home ( Angermann , Bachmann ).

Foreign language borrowings

In the early New High German period, as in earlier and later epochs, active trade contacts between German cities and other countries contributed to the inclusion of many foreign-language words. In the late Middle Ages, Italian was of particular importance - in the field of money and trade, Italy was far superior to other European countries. For example, Italian comes from words like bank , risk , golf , compass , captain .

During the Renaissance, Italian influences continued, for example in the field of music ( viola , harpsichord ). Since the second half of the 16th century, more and more French words appeared in German, which was an expression of the charisma of French culture and the absolutist politics of France, whose models the German nobility and German princes tried to follow. Words from French were taken from the fields of court life ( ball , ballet , promenade ), kitchen ( compote , chops , jam ), fashion ( hairstyle , wardrobe , costume ) or the military ( army , lieutenant , officer ).

Humanism, beginning of the scientific study of the language

From the first half of the sixteenth century the ideas of the Renaissance and humanism began to penetrate Germany to a large extent . Although these currents are usually associated with the return to classical Latin and the ancient Greek language, they also contributed to the development of the German language. More and more scholars wrote their works in German, for example Paracelsus , author of the book Die Große Wundarznei (1536). Historical works such as Germaniae chronicon or Chronica des gantzen Teutschen lands, aller Teütschen [...] (Apiario, Bern 1539) by Sebastian Franck , and finally, especially after the beginning of the Reformation in 1517, theological writings were also written in German.

The 16th century also saw the beginning of the academic study of the German language, although the works that discussed linguistic topics were often still written in Latin. The fruit of the humanistic interests of German scholars were German-Latin dictionaries, such as the Dictionarium latino-Germanicum by Petrus Dasypodius (1535), the first dictionary of the German language developed according to scientific principles, or the dictionary of the same name by Johannes Fries from 1541.

The first theoretical treatises on the German language also date from the 16th century, namely grammars (for example Ein Teutsche Grammatica by Valentin Ickelsamer from 1534) and spelling manuals (for example Orthographia by Fabian Frangk from 1531).

Language societies

Following the pattern of foreign societies (for example the Italian Accademia della Crusca ), language societies also emerged in Germany that aimed to maintain the national language and literature. The first and best known of them was the Fruit Bringing Society, founded in Weimar in 1617 . The members of these societies as well as poets (such as Martin Opitz , Andreas Gryphius , Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen ) endeavored to upgrade the German language. To this end, the so-called language purists fought with varying degrees of intensity against the “Wortmengerey” in the German language. For example, while Zesen himself wanted to translate foreign words such as “nature” into “witness mother”, Leibniz represented a moderate linguistic purism. Many of the shapes they proposed gained acceptance, but not immediately, but only increasingly in the 18th century: diameter and testator , which replaced the older terms diameter and testator . Sometimes the new German word has been adopted into the public domain without the foreign word has been replaced (for example, fragment , correspondence , library , instead of the fragment , correspondence and library have been proposed); but sometimes the proposals failed, like the words daily candlestick and Zitterweh containing the words window and fever should replace (both Latin origin). We owe to the efforts of the language societies and German counterparts grammatical terms such case (meaning "Case"), Gender word ( "Product"), a noun ( "noun") and spelling ( "orthography").

The language societies, however, did not have the greatest history of impact through their Germanization and the (impossible) defense against foreign influences. Rather, in terms of linguistic history, the codification and standardization of the German language remained a groundbreaking contribution to the development of German. However, the efforts (according to CJ Wells ) had no impact on the modern standard language .

Spelling and Punctuation

The first attempts to formulate orthographic rules were made in the early New High German era.

Above all, there is the question of capitalization of nouns. The assumption of the rule that all nouns should be capitalized was a lengthy process that had started in the Middle High German period, lasted over the entire period of Early New High German and only largely in the next period (in New High German - middle of the 18th century) was completed. Initially, only certain words, especially those from the religious sphere, were emphasized by setting them in capital letters ( e.g. God ). The process continued in the 16th and 17th centuries; but there were no clear rules here - scribes used capitalization to highlight those nouns that they considered important. The following table shows differences in capitalization in two translations of Psalm 17:

| Luther's translation (1523) | Translation from 1545 |

|---|---|

|

|

We also owe the early New High German period the use of the first punctuation marks , which were basically still missing in Middle High German. At first only the point at the end of the sentences was used. In order to emphasize the breathing pauses when reading, the so-called Virgeln ( slashes ) began to be used in the 16th century , as can be seen in the following quote from the letter from Martin Luther's interpreting from 1530:

... that one does not have to ask the letters in the Latin language / how to speak German / how these donkeys do / but / one has to ask the mother at his house / the children on the streets / the common mā on the market drum / from the same open mouth / how you talk / and then dolmetzschen / that is how you understand it / vn notice / that one speaks German with jn .

The slashes were not replaced by today's commas until the end of the 17th century, i.e. already in the next (New High German) period. The first examples of the use of the exclamation mark (!), The question mark (?) And the semicolon (;) also come from the 17th century .

Development of the common German language