Racial disgrace

Rassenschande (also known as blood shame ) was a widespread propaganda term in the National Socialist German Reich , with which sexual relations between Jews - according to the definition of the Nazi racial laws - and citizens of "German or related blood" were denigrated. Marriages between Jews and " German-blooded " were described as racial treason . In 1935, marriages and sexual contacts of this kind were banned and threatened with imprisonment .

A decree issued a little later extended the ban on marriage to other groups: as a matter of principle, all marriages that endangered the “keeping of German blood ” were to be avoided . A circular listed " Gypsies , Negroes and their bastards ".

Sexual intercourse between members of different “races” was also made under threat of punishment in other countries.

Ideological historical background

The terms “race” and “bloodshed” were already popular topoi in the völkisch movement , which discussed and propagated them within the framework of eugenic racial theories . On the German Day in Weimar in October 1920 , the executive chairman of the German National Protection and Defense Association , Gertzlaff von Hertzberg , warned the Germans not to commit racial disgrace. In a brochure published by the Meißen local group of the Schutz- und Trutzbund with the title An unconscious bloodshame - the fall of Germany. Natural laws about race theory from 1921 said:

“Mixing races and species is a sin against the blood and leads to perdition. Incest has destroyed the peoples of the earth. "

The leader of the German Völkisch Freedom Party and temporary NSDAP regional leader of Thuringia, Artur Dinter , anticipated essential contents of the Nuremberg Laws with his demand in 1924:

“The German people must be protected against Jewish desecration and bastardization. Marriages between Germans and Jews are to be forbidden by law. A Jew who seduces a German girl or a German woman [...] is punished with imprisonment. "

The terms were also prominent during the völkisch agitation against the Allied occupation of the Rhineland after the end of the First World War. Since French soldiers of African origin were also deployed here, a veritable propaganda campaign against the “ black disgrace ” was carried out by the ethnic group, in which the colonial soldiers were portrayed as brutal savages who sully the “German blood” through sexual assaults on German girls and women would (cf. “ Rhineland Bastard ”). In the Deutschvölkische Blätter of the Schutz- und Trutzbund it said on this subject, among other things:

“What does the world say about the increasingly frequent crimes of the wild beasts against defenseless German women and children? Do the white peoples of the world know about it? It must be doubted, because one cannot believe that all of them have no feeling for the racial shame that is being done to us and thus also to them as white peoples. "

Laws and Regulations

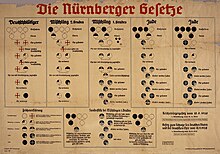

The “Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor” of September 15, 1935 (RGBl. I p. 1146; also called “Blood Protection Act” for short) is one of the two Nuremberg race laws . The law was drafted in a hurry and came as a surprise to the public.

In anti-Semitic circles, however, the basic idea was not new and can be traced back to 1933. After the " seizure of power ", "racial abuse" were publicly denounced; In individual cases there were attacks by the SA and kidnappings in “ protective custody ”. Proposals and draft laws “regulating the position of the Jews”, such as those sent by Rudolf Hess to Julius Streicher on April 6, 1933 , anticipated the provisions of the later “Blood Protection Act” and in some cases contained stricter provisions than the Nuremberg Laws.

The Blood Protection Act prohibited marriages between Jews and "German-blooded" people. The "First Ordinance of the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor" of November 14, 1935 specified that marriage between Jews and " second-degree Jewish mongrels " with only one Jewish grandparent was also prohibited, as these were the "German-blooded" should be attributed. “ Jewish first-degree mixed race ”, descended from two Jewish grandparents, were only allowed to marry “German-blooded” or “second-degree Jewish mixed-race” people with special permission. For the decision, the "physical, mental and character characteristics of the applicant, the length of his family's residence in Germany, his or her father's participation in the world war and other family history" had to be assessed. A marriage between two quarter Jews "should not be concluded."

The marriages between Jews and "German-blooded" people declared illegal within the framework of the law, which were entered into abroad by circumventing the ban, could be declared null and void and those involved were threatened with imprisonment . For sexual intercourse outside of marriage, the criminal provision in Section 5 (2) read: "The man [...] is punished with imprisonment or penitentiary." The provision that only the man is subject to punishment is said to have been inserted on instructions from Hitler . In the relevant commentary of the law, the reason given is that the woman's testimony is necessary for the transfer and that she no longer has the right to refuse to testify if released from punishment .

On June 22, 1938, the Reich Ministry of the Interior issued a decree according to which Jews were to be placed in hospitals in such a way “that the danger of racial disgrace is avoided. Jews are to be accommodated in special rooms. "

The penalties in the law were vague and broad. The formulation deliberately gave judges the opportunity to punish Jews more severely than the "German-blooded" men ( rubber paragraph ). Mitigating or aggravating offenses were not defined in this law and the penalties ranged from one day in prison to a prison sentence of 15 years. The anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer continued to call for the death penalty .

Convictions

Between 1935 and 1943, 2,211 men were convicted of "racial disgrace". The number of preliminary investigations initiated was considerably higher; usually a denunciation triggered the investigation. A regional evaluation of the judgments shows that Jewish men received significantly higher sentences than "Germans with blood". In a third of the judgments against Jews, prison terms of between two and four years were imposed; almost a quarter of those judged were punished even more severely. A maximum sentence of 15 years was rarely given.

The Reichsgericht's interpretation of the term “extra-marital intercourse” was already rampant in 1936 and placed “such activities” under the law, “by which one part wants to carry out his sexual instinct in a way other than sexual intercourse .” This interpretation made it possible to punish even caresses and kisses as racial disgrace. In the notorious death sentence against Leo Katzenberger , the judges then referred to the “ Ordinance against pests of the people ” because the alleged act took place under the protection of the blackout. There are five other known cases from 1941 to 1943 in which judges imposed the death penalty, which is not actually provided for in the Blood Protection Act, by invoking tightening provisions against "blackout criminals" or " dangerous habitual criminals " (as in the Werner Holländer case ).

Although the law gave the woman impunity, she could be punished for favoritism or perjury if she tried to protect her partner. Often the woman was taken into protective custody until the end of the proceedings , sometimes under the pretext of having to rule out the risk of recurrence. This undermined the provision of the law until Hitler himself intervened and a supplementary ordinance was issued on February 16, 1940, according to which women should be expressly exempt from punishment for alleged favoritism. The threat of perjury and aiding and abetting remained unaffected . The Gestapo had gone over from mid-1937 to correct her mild published court decisions and take the "Jewish Rasseschänder" in custody. From 1937 onwards, some Jewish women were evidently sent to a concentration camp after a trial had been completed , where there was a separate label for this group of people .

The Blood Protection Act contributed significantly to the growing social isolation of Jewish Germans . It thus laid a foundation for the later persecution and mass destruction in the Holocaust .

See also

literature

- Cornelia Essner: The "Nuremberg Laws" or the administration of the racial madness 1933-1945 . Schöningh, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-506-72260-3 . (basic scientific investigation)

- Irene Eckler (Ed.): The Guardianship Act 1935-1958 . Persecution of a family for "racial disgrace"; Documents and reports from Hamburg. Horneburg, Schwetzingen 1996, ISBN 3-9804993-0-8 .

- Jörg Friedrich : acquittal for the Nazi judiciary . The judgments against Nazi judges since 1948. Documentation. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1983, ISBN 3-499-15348-3 , p. 261-321 .

- Lothar Gruchmann: “Blood Protection Act” and justice. On the origin and effect of the Nuremberg Law of September 15, 1935 . In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte . tape 31 , no. 3 , 1983, p. 418-442 ( PDF ).

- Gerhard Henschel : shouts of envy . Anti-semitism and sexuality. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-455-09497-8 . (also: historical derivation of the Globke laws)

- Ingo Müller : Terrible lawyers . The unresolved past of our judiciary. Kindler, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-463-40038-3 , pp. 105-123 .

- Alexandra Przyrembel : "Rassenschande" . Purity myth and legitimation for extermination under National Socialism. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht , Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-525-35188-7 .

- Hans Robinsohn: Justice as political persecution . The case law in cases of racial disgrace at the Hamburg Regional Court 1936–1943. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3-421-01817-0 .

- Franco Ruault: "New creators of the German people" . Julius Streicher in the fight against "Rassenschande". Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-631-54499-5 .

- "Of habitual criminals, pests of the people and anti-social ..." Hamburg judicial judgments under National Socialism / Hamburg judicial authority (ed.). 1st edition. Results, Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-87916-023-6 , p. 105 ff . (Figures, dates, quotation from the Reichsgericht)

Web links

- Poster for the anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer (Note: The death penalty for R. mentioned in the headline did not exist in 1935 or later)

- Birthe Kundrus: "Forbidden Dealing": Love Relationships Between Foreigners and Germans 1939-1945 (PDF)

Evidence

- ↑ Saul Friedländer : The Third Reich and The Jews. The years of persecution 1933-1939 . Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-43506-8 , p. 170.

- ↑ Walter Jung: Ideological requirements, content and goals of foreign policy programs and propaganda in the German-Volkish movement in the early years of the Weimar Republic: the example of the German-Volkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund (PDF; 5.4 MB) . University of Göttingen 2001, p. 70 f.

- ↑ Quoted from Jung 2001, p. 65.

- ↑ Quoted from Cornelia Essner: The alchemy of the concept of race and the 'Nuremberg Laws'. In: Yearbook for Research on Antisemitism 4, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-593-35282-6 , p. 201.

- ↑ Iris Wigger: " Schwarze Schmach ", in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns .

- ↑ Deutschvölkische Blätter number 21 of May 26, 1921, p. 82, quoted from Jung 2001, p. 141.

- ^ Blood Protection Act on Wikisource

- ↑ Wolf Gruner (edit.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945. Vol. 1., German Empire 1933–1937. Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58480-6 , Doc. 27, pp. 123-129.

- ↑ 1. VO of the law for the protection of German blood and German honor (1935, RGBl. I, 1334f)

- ↑ Knut Mellenthin : Chronology of the Holocaust

- ↑ Alexandra Przyrembel: "Rassenschande". Purity myth and legitimation for extermination under National Socialism. Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-525-35188-7 , p. 499.

- ↑ According to A. Przyrembel: "Rassenschande" ... ISBN 3-525-35188-7 , p. 499, there were 5,152 preliminary investigations in Berlin that led to 694 criminal proceedings.

- ↑ on this Ingo Müller: Furchtbare Juristen ... Munich 1987, p. 107 f.

- ↑ A. Przyrembel: “Rassenschande”… ISBN 3-525-35188-7 , p. 507 lists 7 cases of protective custody and 2 cases of concentration camps for Düsseldorf.

- ↑ Reading sample here