National Socialist Propaganda

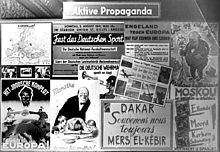

The Nazi propaganda (even Nazi or Nazi propaganda ) was one of the central activities of the Nazi Party (NSDAP). During the Weimar Republic it served the goal of taking power , during the time of National Socialism in the German Reich it served the "realization of the cultural will of the Führer" and the "penetration of the entire German people with the National Socialist worldview." The purpose of propaganda was press and radio and film used.

Central themes of the National Socialist propaganda were the so-called stab in the back legend and the Versailles dictation , the conspiracy of the alleged world Jewry and the closely related anti-communism (fight against Jewish Bolshevism ), the ideology of the national community , the glorification of the fallen of the movement and the memory of heroes , the National Socialist The image of women and the unconditional cult of the Führer around Adolf Hitler as a dictator. The revision of the German territorial losses as a result of the Peace Treaty of Versailles under the catchphrase Heim ins Reich and the legend that Germany was a people without space and had to conquer living space in the east served directly to prepare for war .

Methodologically, the Nazis' propaganda concentrated on a few topics, which they processed into memorable slogans that appeal to emotions . In doing so, it followed the guiding principles of propaganda that Adolf Hitler had already described in his basic work Mein Kampf , written between 1924 and 1926 : “This is precisely the art of propaganda, that it, grasping the emotional world of the large masses, is psychologically correct Form finds the way to the attention and further to the heart of the masses ”.

Important means of dissemination of Nazi propaganda were books and newspapers, but also new media such as radio and film. A central component of Nazi propaganda was in particular the National Socialist film policy . Public gatherings and marches, school lessons and own organizations such as the Hitler Youth (HJ) or the Bund Deutscher Mädel (BDM), but also material benefits for the population , played an outstanding role . The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda , headed by Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels , was an essential institution for the dissemination and control of National Socialist propaganda .

development

Guidelines for National Socialist Propaganda in Hitler's "Mein Kampf"

In his book Mein Kampf , written between 1924 and 1926, Hitler developed the essential basic patterns and guidelines for later National Socialist propaganda. Propaganda must be aimed primarily at feeling and only to a very limited extent at intellect. It has to be “popular and adjust its intellectual level to the receptivity of the most limited of those to whom it intends to address.” It is “wrong to want to give propaganda the versatility of, for example, scientific instruction.” Hitler clearly admits on the manipulative handling of propaganda with objectivity and truth. Propaganda "does not objectively research the truth, insofar as it is favorable to others, in order to then present it to the masses with doctrinal sincerity, but rather to continuously serve its own".

As an essential principle of propaganda aimed at the broad mass of the population, Hitler formulated the restriction to a few topics, thoughts and conclusions that would have to be persistently repeated.

Victor Klemperer later described the way the National Socialists dealt with language in his work LTI - Notebook of a Philologist and comes to the conclusion that the National Socialists' rhetoric influenced people less through individual speeches, leaflets or the like, but rather through the stereotypical repetition of them over and over again the same terms and phrases filled with National Socialist ideas .

National Socialist propaganda before 1933

organization

In the course of the re-establishment of the NSDAP in 1925 and its organizational consolidation, the office of Reich Propaganda Leader of the NSDAP was established. Initially, the vertical expansion of the propaganda work took place, above all the expansion of the so-called propaganda cells at the Gauleitungen and local groups. The guidelines for propaganda campaigns drawn up by the deputy Reich propaganda leader Heinrich Himmler in 1928 were intended to serve as the core of National Socialist propaganda, especially for the preparation and implementation of major National Socialist events.

After Hermann Esser and Gregor Strasser , Joseph Goebbels was appointed Reich Propaganda Leader in 1930 , and on March 14, 1933, he became head of the newly established Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda . For the first time in the Reichstag election campaign in 1930 and later in the elections in July and November 1932 , the NSDAP carried out election propaganda that was previously unknown in Germany in this professional form, for example through the use of trained Reich speakers .

Organizationally, the Proganada leadership was assigned to the Reich Propaganda Leadership of the NSDAP and was based in the Munich party headquarters ( Brown House ). After 1933 a liaison office was set up in Berlin, so that part of the work gradually shifted there.

Content

After the failed Hitler putsch in Munich in November 1923, Hitler set a new route for the NSDAP . It said that the coup tactic should be replaced by a new "legality tactic" in order to come to government in a legal way. To do this, it had to cast off the image of a radical splinter group and create a mass base for itself. The organizational work of the democratic parties should serve as a model. Political opponents as well as parliamentarism should be defeated with their own weapons.

In order to achieve a “ mobilization of the masses ”, the emphasis of the political work was placed on propaganda. Hitler already in Mein Kampf developed principles

- Limited to a few topics and keywords,

- low intellectual demand,

- Aiming at the emotions of the masses,

- Avoidance of differentiations,

- and the thousandfold repetition of the respective beliefs

now determined the course of the National Socialist propaganda, which thus became a highly successful weapon of the Nazi apparatus.

National Socialist propaganda was also a counter-concept to the methods of the democratic parties, whose political advertising was more based on rational argumentation. In contrast, Nazi propaganda relied on the deliberate renunciation of explanations, an appeal to the irrational and the emotionally charged friend-foe cliché. The rally speeches, which were the National Socialists' most important agitation instrument until 1933 , therefore did not have the task of explaining the election manifesto and the political goals of National Socialism on the basis of concrete plans , but rather a - in detail not defined at all - "general belief in National Socialism “ Be conveyed. With regard to possible future perspectives, the propagandists proceeded according to the recipe of promising everything to everyone and avoiding concrete commitments.

National Socialist propaganda after the seizure of power in 1933

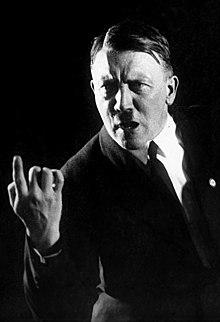

Minister Joseph Goebbels speaks on August 25, 1934 in the Berlin Lustgarten on the occasion of an SA appeal.

The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda was set up on March 13, 1933 - one day after Hitler had ordered the " conformity of the political will of the states" in Munich as a result of the National Socialist seizure of power . Goebbels , who was now promoted to Reich Propaganda Leader and Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda in personal union , was a very close confidante of Hitler and was able to decisively expand his sphere of influence, since practically all opposition media were switched off at one stroke.

On behalf of Goebbels, Walter Tießler built the Reichsring for National Socialist propaganda and public education in 1934 . Before that, the task of centralizing propaganda had been carried out by the Office of Concentration in the Reich Propaganda Administration. “With the creation of the Reichsring in 1934, the propaganda and educational work of the offices, branches, affiliated associations, the professional and professional organizations as well as numerous associations were brought under uniform control. A Reichsring I was formed in which all party organizations are represented. In a Reichsring II, all other Reich organizations that have propagandistic tasks were looked after, ”said Tießler in 1944. The Reichsring evaluated the people's court trials in particular propagandistically and monitored the use of speakers by the German Educational Institute and the German Labor Front's performance enhancement organization as well as other adult education organizations. As head of the liaison office in Berlin, Wilhelm Haegert from 1937 and Walter Tießler from 1941 had the task of "centralizing all communications with the Reich ministries, authorities and public bodies, etc. and carrying out all communications with them." the propaganda come to the knowledge of the Reich authorities concerned. On the other hand, the liaison office brought all tasks and orders issued by the Reich Propaganda Ministry to the attention of the Reich Propaganda Administration.

In order to reach the broadest possible spectrum of citizens via radio , a radio device specially developed at the instigation of the National Socialists , the " Volksempfänger " , went into series production in 1933 . Because of its low price of 76 Reichsmarks (a fraction of the cost of a conventional tube receiver of 200 to 400 RM), this device was easily accessible to the majority of the population. A greatly simplified device, the popularly known as the “Goebbelsschnauze”, the “German Small Receiver” ( DKE 38 ), came onto the market in 1938 at a price of 35 Reichsmarks. The radio therefore soon developed into an influential medium of Nazi propaganda. But since the population quickly got tired of constant political and propaganda sound, Goebbels felt compelled to make the program of the regional broadcasting companies , which had been part of the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft since 1925 , more attractive and varied by means of request concerts, radio plays and sometimes adventurous Wehrmacht reports. From 1 January 1939 until the war's end that sent major German broadcasting a single radio program. See also: Radio propaganda in World War II .

Wall newspapers like the slogan of the week were posted publicly.

In addition, it was important to determine tendencies of opinion in the population and to orient the propaganda accordingly. It had to adapt to the changing moods as daily as possible. After the November pogroms of 1938 (the so-called Reichskristallnacht ), the destruction of almost all synagogues, numerous Jewish shops and institutions as well as the apartments of German Jews throughout the Reich organized by the National Socialist regime, a certain distance from such economically damaging factors was possible both within society and within the party Identify excesses of violence. As a result, the racist propaganda was temporarily reduced. From this point on, the harassment of the Jewish community took a back seat. It was found that the population was more likely to accept the Nazis' pogrom policy towards Jews and political opponents "as long as the persecution was relatively discreet and legal ."

Towards the end of the Second World War , in view of the increasingly hopeless military situation, the focus was increasingly on appealing to the population's willingness to make sacrifices for the - increasingly improbable - final victory on the radio and especially in the German newsreel . The loud certainty of victory of the first years of the war gave way to simple slogans to keep going.

Strategies

Political rhetoric

Under National Socialist influence, the evaluation of numerous terms changed radically. Terms that were morally negative in the bourgeois society of the Weimar Republic were now modeled into positive values by Nazi propaganda. The adjective “ruthless”, for example, was often used in the language of the National Socialists to mean “determined” or “energetic”, i.e. in the sense of a positive quality. In a similar way, " hatred " also became a positive value in certain contexts: the "heroic hatred of the Nordic race" was contrasted with the "cowardly hatred of Judaism ".

Another characteristic of propaganda language was the use of a "rhetoric of violence". Hitler's speeches in particular were riddled with extremely aggressive, defamatory and foul attacks against political opponents. These have been called the worst criminals and have been charged with fraud, sabotage, rascality, fraud and even murder. The Jews in particular were rhetorically demonized, at the same time morally devalued and “dehumanized” through a certain use of language - for example through animal comparisons. Swear words such as “ parasite ”, “bug”, “roundworm” and “vermin” were supposed to cause the listener to lose empathy and to show no sympathy for the attacked. Instead, the physical "extermination" or annihilation of parts of the population that the National Socialists viewed and labeled as harmful to the national community should be made plausible through appropriate associations . In order to fight the " enemies of the people ", Nazi speakers, above all Hitler and Goebbels, repeatedly called for the "radical elimination of danger" (Goebbels in the Sportpalast speech in 1943) and for the "extermination of European Jewry" (Hitler). The Nazi publicist Johann von Leers played a special role in connection with anti-Jewish propaganda .

Leader cult

The stylization of Adolf Hitler as an unapproachable and glorified leader figure raised above all doubt was a central task of Nazi propaganda ( leader cult , leader principle ). For this purpose, Hitler's dubious past was veiled and downright mystified with positive assumptions. Blind trust in the competence of the “leader” should be generated. “Leader commands we follow” has become a widely used slogan. Not only the German population, but also the leadership of the NSDAP succumbed to this stylization. As was shown in the research project “History and Memory” through interviews with Nazi supporters, an interplay between Nazi propaganda and supporters must be assumed: On the one hand, a large part of the German population full of feelings of shame, unprocessed world war trauma, regression and redemption fantasies served by the other side, the Nazi propaganda. High-ranking Nazi politicians withheld their doubts about certain political projects less out of fear of denunciation than out of excessive identification with the almighty father figure. Hermann Göring put this aptly: “I have no conscience! Adolf Hitler is my conscience. "

On 20 April, with annual ceremony of the leaders Birthday committed.

On the other hand, attempts were made at the same time to counteract the mystification and exaggeration of Hitler by portraying his person as “a person like you and me”. In 1932, for example, Heinrich Hoffmann presented in his brochure Hitler as nobody knows him, the “Führer” as a child lover, an avid hunter, a dog lover or a technology-loving motorist. The idyllic Berghof served as a backdrop for photos. Overall, there was an ambivalent picture of Hitler, who contrasted his distant remoteness with modernity, vitality, frugality or love of nature ( see also: Animal protection under National Socialism , nature protection under National Socialism ). Hitler and other National Socialist sympathizers of vegetarianism were also influenced by Wagner's book Religion and Art , in which meat consumption and cooking were criticized as Semitic, non-Aryan heritage.

Mass cult and rituals

After their electoral success and the NSDAP seizure of power in 1933, the so-called “national movement” was largely controlled by means of symbolic communication . Using certain rituals , a pseudo-religious form of a political mass cult was created. This cult should appeal to the senses, arouse emotions and numb the mind. Through rallies, torchlight procession, flag roll calls, mass marches and celebrations, as well as through youth organizations such as HJ and BDM, but also through appropriate organization of school lessons, the NSDAP succeeded in skillfully serving the widespread need for identity and social community and using it for political purposes.

Hitler drew inspiration for this form of systematic influence on the masses, among other things, from the book Psychology of the Masses (1895) by Gustave Le Bon . A key to the success of Nazi propaganda lay in the consciously and purposefully employed mass psychology .

The French psychoanalysts Bela Grunberger and Pierre Dessuant quote from a conversation with Primo Levi , who said, "that with Hitler for the first time in history a particularly powerful and violent man [...] used the spectacular weapon of mass communication." Levi also had highlighted the "fascination of the Nazi ceremonies": "When hundreds of thousands shouted in unison, 'We swear it', it was as if they had become one body."

Welfare and consumption

Another instrument for influencing the population, organized by the Nazi state and taken up by propaganda, was a variety of material benefits. As the historian Götz Aly showed in Hitler's People's State , Jewish property stolen by the National Socialists - in the form of furniture, clothing and jewelry, but also in the form of expropriated financial assets - was distributed among the population in order to gain the favor of the population 'Buy'. Aly therefore describes the Nazi regime as a “dictatorship of convenience” . The “social and national revolutionary utopia ” that the NSDAP made popular with the vast majority was the “social people's state”, whose benefits were financed at the expense of others, namely through the robbery of Jewish property, military looting of foreign countries and forced labor .

This kind of courtesy dictatorship also included benefits "given away" by the regime and recreational vacations as part of the " Strength through Joy " (KdF) program, but also inexpensive consumer goods . The " Volkswagen " developed on behalf of the National Socialists in this context was not produced until after the end of the war .

subjects

Racism and Social Darwinism

An important cornerstone of the National Socialist ideology was racism, interspersed with pseudo-scientific elements . With reference to racial theories that were scientifically untenable, but at the time quite popular , attempts were made to distinguish the “German race”, the Germanism of the “Nordic Aryans ” (with the famous formula “blond and blue-eyed”) from other “races” (such as the “Slavic Race "), which were devalued as" subhuman ", should be presented as more valuable (→ master race ). In the spirit of consistent social Darwinism, permission was derived from the “natural superiority” of Germanness to subjugate and suppress other “ peoples ” in a “ racial struggle ”. The “German race”, according to the ideology, is by nature intended to “lead”, which means that the leadership cult within society was also transferred to external relationships, always legitimized by seemingly scientific theories. The Second World War was presented in this context as the biological struggle of the German people for more living space in the east . An important figure in this context was the image of the " people without space ", coined by Hans Grimm and adopted by the National Socialists . The propaganda located the need for settlement "in the east" and no longer overseas, as the German colonial movement had done in the Weimar period. However, the colonial revisionism was continued in the Nazi era to refute the so-called "colonial guilt lie". This should demonstrate the German ability to rule foreign peoples. The campaign to restore the former colonies could only be justified with the need for raw materials.

Nazi health policy included cruel medical research on alleged "subhumans". Robert N. Proctor points out that Nazi health policy and health propaganda also contained some scientific advances in addition to their extermination practices. German doctors were the first to establish a connection between tobacco smoke and lung cancer, and the National Socialists encouraged bakeries, among other things, to bake whole-grain bread. The health policy goals and preventive campaigns in the Third Reich , however, only applied to one's own “national body”.

anti-Semitism

A central motif of Nazi propaganda was “eliminatory anti-Semitism ” ( Daniel Goldhagen ). The worldview of the National Socialists was dominated by the enemy image of Judaism , which in the form of a world conspiracy theory was assumed to be responsible for both modern capitalism (the " eternal Jew " as a representative of finance capital ) and for communism or " Bolshevism ". The connection between the two enemy images of the “Bolshevik Jew” and the “Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy”, as it was especially imagined by Alfred Rosenberg , the “chief ideologist” of the National Socialists, circulated as a veritable “conglomerate of evil” . This propaganda later served, among other things, the ideological preparation of the Eastern campaign as a war of annihilation .

In order to initiate and legitimize the Holocaust of the European Jews propagandistically, propaganda films such as Jud Süss , in which the Jews were portrayed as a “corrupt race”, or pseudo-documentaries such as The Eternal Jew , in the Jew with Rats, were used and vermin were compared. The strategy of propagandistic dehumanization ( dehumanization ) also served to lower the inhibition threshold for those who were directly involved in the crimes of the National Socialists (especially in the concentration and extermination camps ) or who, for example as neighbors, witnessed crimes. The weekly newspaper Der Stürmer , published by Julius Streicher from 1923 onwards , which stylized “the Jews” as an enemy image in a inflammatory language , also served to get in the mood for the Holocaust and its legitimation .

On the other hand, the well-being of European Jews was always proclaimed to the outside world, the mass murder was not made public. In the film Theresienstadt - A Documentary Film from the Jewish Settlement Area from 1945, also known under the euphemistic title Der Führer Gives the Jews a City , the living conditions in the Theresienstadt concentration camp are presented as a “benefit” of the National Socialists.

National community and heroism

Through a clear demarcation between friend and foe as well as a pedantic elaboration of the differences between the two, mostly based on racist ascriptions, as well as the cultic reference to terms such as community , comradeship , home , nation and people , an artificial sense of togetherness, the fiction of a homogeneous " national community " created to which all "Germans" should belong. This community, based on the blood-and-soil ideology , to which there was constant appeal, should not least in the war against the external enemy as a "community to death" in the form of unconditional heroism and the absolute soldier and civil sacrifice for the nation prove.

The admiration of “German virtues” such as strength, courage to fight, discipline and “iron will” went hand in hand with a pronounced resentment against anything intellectual that was viewed as “Jewish”, as well as with a rejection of modernity , which was understood as “racial degeneration” where Judaism was also made responsible for the “cultural decline”. Works of modern art , especially expressionism , were designated as " degenerate art " and withdrawn from circulation or destroyed, as a result of which important works by well-known artists were permanently lost. In addition to scientific works, books that contradicted the regime in terms of ideology , especially works by left-wing authors (including some of the most important writers of the Weimar Republic such as Bertolt Brecht or Heinrich Mann ), were also banned and destroyed as "un-German" in public book burns .

The Nazi Art itself was aimed at the ideal of popularity out in the literature have included home novels popular. In addition to the portrayal of peasant simplicity, the visual arts were also outwardly based on the ideal of ancient Greece and classicism and, for example in Arno Breker's sculptures or the films of Leni Riefenstahl , showed primarily "German fighters" in heroic poses, portraying the well-formed , staged physically superior " Aryan heroes", but also muscular workers , especially craftsmen, doing heavy physical work in "self-sacrificing service for the nation".

The very popular song "Do you see the dawn in the east" with the catchy refrain " People to the rifle " also served as preparation for war .

Image of women

The idea of a woman was propagated as a portrait of naturalness, truth and eternity, whose “unqualified female body should become a suitable symbolic container for the National Socialist ideology”. The woman became the ultimate bearer of National Socialist ideology when the majority of conscripted men were already fighting at the front. The women had to fight on the "home front" in their own way.

On the one hand, an almost religiously propagated mother cult, which was opposed to an aggressive ideal of masculinity, was indulged; on the other hand, there was parallel - and contradicting this - the image of the independent, strong woman, as it corresponded to the BDM ideal. But if girls between 14 and 18 years of age enjoyed the freedoms of the BDM apart from their forthcoming “motherhood duties”, there was an even greater reduction in women to “care and offspring” within the Nazi women's group , propagated as the natural “living space” of a “modern” woman .

The idea of the strong family with the heroic mother fighting for the national community was evoked against the background of the economic crisis and political uncertainty. A stable domestic framework was propagated, which suggested a separation of public and private sphere, but which was actually intended to covertly prepare individuals for the social demands of National Socialist rule. The "emptying of private households by involving citizens in state-controlled leisure activities" was systematically initiated. Women's politics also promoted the de-privatization of the family. Reichsfrauenführer Gertrud Scholtz-Klink called for the submission of women to the Führer and Fatherland, although she saw the main task of women in the private sphere.

media

National Socialist propaganda is characterized by its close and open connection with the new technical mass media , especially film and radio . But traditional media such as books and the press were also used extensively.

Press

The impact of the press on society is of great importance for any propaganda. Hitler wrote: "The press influence on the masses is by far the strongest and most urgent, since it is not used temporarily but continuously" .

The press was controlled on four levels.

1. Institutional governance

In 1933 Hitler appointed 3 Reichsleiter with media skills.

Otto Dietrich as Reich Press Chief of the NSDAP took over the management of the press office and the correspondence of the NSDAP. In 1937 he was appointed head of the press department of the Reich government, whose main task was to "inform and direct the German daily newspapers".

As Reichsleiter for the press, Max Amann took over the management and coordination of the Nazi party press and the central party publishing house .

Joseph Goebbels as Reich Propaganda Leader took over the management of the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda and the management of the Reich Chamber of Culture (divided into 7 chambers).

2. Legal control

In 1934 the Editor's Law was passed, which aimed to bring press journalists into line.

All major German-language Swiss newspapers were banned in Germany by 1935 (in Austria, meanwhile, there was a standstill agreement against German propaganda offensives).

From 1937 there were regulations and restrictions for the allocation of paper. From 1941, bans were added to increase circulation. In 1944, the number of newspapers for enemy propaganda was also limited.

3. Economic press control

The aim here was complete control and the break-up or taking possession of all press publishers. The central management was with Max Amann.

The Amann orders of 1935 were an important measure to control press publishers. In this context, scandal press and press for special target groups were banned. Publishing houses could be closed due to undesirable competitive conditions and were not allowed to be owned by Jews.

4. Content control of the press

In 1933 the German news office became state property. In addition, daily press conferences of the Reich government for selected journalists were held between 1933 and 1945, which contained detailed instructions and prohibitions on content, placement, design and scope. The journalists were prohibited from doing their own research. These conferences were documented in minutes that were destroyed at the end of the month.

Movie

According to Goebbels, “a good government without propaganda [...] could just as little exist as good propaganda without a good government. Both must complement one another ”. Goebbels described the medium of film as “the most modern means of influencing”.

Even before it came to power, the NSDAP used the film medium. For the first time, election advertising by Nazi leaders was shown in cinemas. After the election victory in 1933, the Reichsfilmkammer was founded. Scriptwriters, directors, actors and even cinema owners had to be members. Jewish artists were excluded. The film industry, which was financially weak during the Weimar Republic , was now subsidized by the state itself. The owner of Universum-Film AG , Alfred Hugenberg , willingly made the largest German film company available for propaganda purposes. Here, too, the Jewish employees were dismissed in order to give the film industry “folkish contours” (Goebbels). In 1937 Hugenberg sold his shares in UFA to Cautio Treuhand , a holding company operating on behalf of Goebbels.

In 1942, UFA was merged with the remaining private film production companies to form the state-owned Ufa-Film GmbH (UFI), and the entire film production in Germany was thus under Nazi ownership. Films that violated “National Socialist, religious, moral or artistic feelings” (Goebbels) were banned. In the event of disobedience, brutal measures were taken. "Artists have to obey the laws of order and national discipline: if they don't want that, they lose their heads like every other citizen", says Goebbels. With an amendment to the Reichslichtspielgesetz, the Propaganda Minister, who saw himself as a “passionate lover of the art of film”, made himself the supreme film master of the Reich.

In order to be able to use the film propaganda as widely as possible, over 1500 mobile film troops were used. They were out and about in regions with no cinemas to show propaganda films . Often these were well attended, also because there were hardly any other entertainment options in the country. In addition, during the Second World War, so-called Propaganda Companies (PK) were set up in the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS , which were supposed to film the events of the war so that the resulting images could later be used for propaganda purposes .

Of the total of around 1200 films produced during the regime , only around 160 were used for direct propaganda. From 1934 every cinema owner was required to show a so-called “ cultural film ” in the opening program. These were short, supposedly factual documentary films on cultural, scientific and other topics; topics such as race theory and anti-Semitism were dealt with here.

The propaganda in the film covered every subject and every genre of the film. The following varieties were preferred by Nazi propaganda:

- Newsreels: The news programs broadcast in the opening programs of the cinema that reported in particular on military events. From 1940 the various existing newsreels were brought into line with the German newsreel , the production of which was personally monitored by Goebbels.

- Cultural films: the already mentioned short documentaries on topics such as race theory, blood and soil .

- Party conference films : They reported in documentary form on the Nuremberg Nazi party rallies . The victory of faith , the triumph of the will or the day of freedom! - Our Wehrmacht by Leni Riefenstahl are considered works of high technical brilliance, which are in the service of Nazi propaganda. The film The March to the Fuhrer also falls into this category .

- Feature films with propagation of the Führer principle: Here the story of a leader, for example that of a historical personality, was presented in order to establish a reference to the present. Examples are films about Friedrich II. Such as Fridericus (1937, directed by Johannes Mayer, with Bernhard Minetti ) or The Great King (1942, directed by Veit Harlan , with Gustav Fröhlich ).

- Perseverance films: After the Battle of Stalingrad at the latest in 1943, general skepticism about the propagated “final victory” grew. Perseverance films that show military defeats that ultimately lead to a brilliant victory should also strengthen the will in the event of a certain defeat. The last film of this kind was Kolberg .

- Propaganda in cheerful films: 90 percent of the films produced during the Nazi regime were so-called H-films (cheerful films). They should distract citizens from worries and problems and subliminally advertise Nazi goals. In Quax, the Bruchpilot with Heinz Rühmann in the lead role, for example, commercials for the Air Force were made in a comedic way .

From 1944 onwards, the production conditions for the film industry deteriorated significantly. Cinemas and production facilities were destroyed, areas occupied. Goebbels tried to keep the film industry alive until the end. Canvases were hung between ruins. While the Soviet troops were approaching Berlin, Goebbels was planning a full-length film about a night of bombing in Berlin entitled Life goes on .

More than 40 former Nazi propaganda films are still subject to a distribution ban and restricted screening options as so-called retained films .

Songs

Songs played an important role in National Socialist propaganda. Well-known propaganda songs are for example the Horst Wessel song or the storm song (“Germany, awake!”).

Postage stamps

As was the case with the Allies , the German side used stamps for propaganda purposes. These were forgeries of brands that were used by the enemy as “standard brands ”. In contrast to so-called war forgeries , in which the attempt was made to copy the original as deceptively real as possible, the propaganda forgeries were brands that were based on the original, but were modified to a greater or lesser extent. By spreading these brands through agents , the population should be unsettled or demoralized.

The German counterfeit brands that were produced from late summer 1944 were directed exclusively against Great Britain and were produced in the Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen concentration camp . This z. B. in the series of stamps, which in 1937 on the occasion of the coronation of King George VI. came out, replaced the portrait of his wife Queen Elizabeth (the Queen Mum ) with that of Stalin. Most of the forgeries existed from the British postal stamp series Michel no. 221–226, which only contains the portrait of George VI. showed. The changes made to the brands were more subtle: hammer and sickle in the rose on the left, star of David instead of a cross on a crown, star of David in a thistle on the right, penny symbols formed from hammer and sickle. In addition, there were often fantasy imprints as well as prefabricated propaganda stamps that were supposed to indicate the alleged imminent loss of the British colonies after D-Day .

See also

- Reichserntedankfest

- National Labor Day

- Reich propaganda leadership of the NSDAP

- Education under National Socialism

- Christmas ring broadcast as an example of propaganda on Nazi radio

- National Socialist Christmas Cult

- Radio propaganda in World War II

- Language of National Socialism

literature

- Hilmar Hoffmann: Myth Olympia. Autonomy and submission to sport and culture. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-351-02232-8 .

- Peter Longerich : “We didn't know anything about it!” The Germans and the persecution of the Jews 1933–1945. Siedler Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-88680-843-2 .

- Peter Longerich: Goebbels. Biography. Siedler Verlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-88680-887-8 .

- Stephan Marks: Why did you follow Hitler? The Psychology of National Socialism. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-491-36004-4 .

- Marie-Helene Müller-Rytlewski: The Extended War - Hitler's propaganda work in a historically disoriented and socially fragmented society. Dissertation . Stolberg 1996.

- Gerhard Paul : Uprising of pictures. The Nazi propaganda before 1933. Verlag JHW Dietz Nachf., Bonn 1990, ISBN 3-8012-5015-6 .

- Georg Ruppelt : Hitler against Wilhelm Tell. The “equalization and elimination” of Friedrich Schiller in National Socialist Germany. In: Reading room: Small specialties from the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Library - Lower Saxony State Library. Issue 20. Verlag Niemeyer, Hameln 2005, ISBN 3-8271-8820-2 .

- Holger Skor: "Bridges over the Rhine". France under the perception and propaganda of the Third Reich, 1933–1939 . Klartext Verlag, Essen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8375-0563-4 .

- Bernd Sösemann: Hitler's “Mein Kampf” in the edition of the “ Institute for Contemporary History ”. A critical appreciation of the demanding edition. In: Jahrbuch für Kommunikationgeschichte , 19th year (2017), pp. 121–150.

- Bernd Sösemann (ed. Together with Marius Lange): Propaganda. Media and the public in the Nazi dictatorship. 2 volumes, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2011.

- Jutta Sywottek: Mobilization for total war. The propaganda preparation of the German population for the Second World War. Opladen 1976.

- Doris Tillmann; Johannes Rosenplänter: Air War and "Home Front". War experience in the Nazi society in Kiel 1929-1945 . Solivagus-Verlag, Kiel 2020, ISBN 978-3-947064-09-0 .

- Birgit Witamwas: Glued Nazi propaganda. Seduction and manipulation through the poster . De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-043808-6 .

- Gordon Wolnik: Middle Ages and Nazi Propaganda: Images of the Middle Ages in the print, audio and visual media of the Third Reich. Lit Verlag, Münster 2004, ISBN 3-8258-8098-2 .

- Clemens Zimmermann: Media in National Socialism. Germany 1933–1945, Italy 1922–1943, Spain 1936–1951. UTB, Vienna a. a. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8252-2911-5 . ( Review ).

- music

- Eberhard Frommann: The songs of the Nazi era. Investigations into National Socialist song propaganda from the beginnings to the Second World War. PapyRossa-Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-89438-177-9 .

- Hans-Jörg Koch: The request concert on Nazi radio. Böhlau, Cologne 2003, ISBN 3-412-10903-7 .

- Press

- Peter Longerich: Propagandists at War. The press department of the Foreign Office under Ribbentrop . Oldenbourg, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-486-54111-0 .

- Andrea Weil: Countering public opinion, Erich Schairer's journalistic opposition to the National Socialists 1930–1937. Dipl.-Arb., Eichstätt 2007; Volume 25 of the history of communication by Walter Hömberg and Arnulf Kutsch, Lit Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-8258-0863-1 .

- Visual arts

- Rolf Sachsse: The education to look away. Photography in the Nazi state. Philo Fine Arts, Dresden 2003, ISBN 3-364-00390-4 .

- Adrian Schmidtke: body formations. Photo analyzes for the formation and disciplining of the body in the education of National Socialism. Münster u. a. Waxmann 2007, ISBN 978-3-8309-1772-4 .

- Wolfgang Schmidt: "Painter at the Front". The war painters of the Wehrmacht and their pictures of fight and death. In: Working group on historical image research (ed.): The war in images - images of war. Frankfurt am Main / New York 2003, ISBN 3-631-39479-9 .

- Books

- Valerie Hader: Fairy tales as a propaganda instrument under National Socialism. Study of the history of communication on the significance of the fairy tale genre within the fascist children's and youth literature policy. Dipl.-Arb. Univ. Vienna, 2000.

- Michaela Kollmann: School books in National Socialism. Nazi propaganda, "racial hygiene" and manipulation. LinkVDM-Verlag Müller, Saarbrücken 2006, ISBN 3-86550-209-1 .

- Gudrun Pausewang: The children's and youth literature of National Socialism as an instrument of ideological influence. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-631-54163-5 .

- Movie

- Style epochs of film: The Nazi film. Philipp Reclam jun., Ditzingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-15-019531-4 .

- From coal stealing and shadow man or: How to sell the war. Frankfurter Studio- und Programmges., Frankfurt am Main 1990.

- Rolf Giesen: Nazi propaganda films: a history and filmography. McFarland, Jefferson, NC 2003, ISBN 0-7864-1556-8 .

- Mary-Elizabeth O'Brien: Nazi cinema as enchantment. The politics of entertainment in the Third Reich. Camden House, Columbia, SC 2006, ISBN 1-57113-334-8 .

- Postcards

- Otto May: Staging of seduction: the postcard as a witness of an authoritarian upbringing in the III. Rich. Brücke-Verlag Kurt Schmersow, Hildesheim 2003, ISBN 3-87105-033-4 .

- Anti-Soviet propaganda

- Jan C. Behrends: Back from the USSR. The Anti-Comintern's Publications on Soviet Russia in Nazi Germany (1935–41). In: Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. Vol. 10, No. 3 (2009), pp. 527-556. doi: 10.1353 / kri.0.0109

Web links

- LeMO : Nazi propaganda

- Bernd Kleinhans: " The newsreel as a means of Nazi propaganda " on shoa.de

- Tobias Jaecker: Journalism in the Third Reich. Possibilities and limits of journalistic opposition

- A German "Prawda" - the "truth" from the hand of the Wehrmacht - via the German four-page weekly newspaper in Russian from August 28, 1941. ( Federal Archives )

- Color photos from propaganda events on Daily Mail

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. Organization book of the NSDAP ed. from the Reich Propagandaleitung of the NSDAP , Franz-Eher-Verlag , 3rd edition 1937, p. 295. archive.org, accessed on February 27, 2020.

- ↑ Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf. Munich 1933, Chapter 6: War Propaganda, p. 198.

- ↑ Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf. Munich 1939, chapter "War Propaganda", Volume I, p. 193 ff.

- ↑ Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf. Munich 1938, p. 197.

- ↑ Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf. Munich 1938, p. 198.

- ↑ Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf. Munich 1938, p. 200.

- ↑ "Any change must never change the content of what is to be brought about by the propaganda, but must always say the same at the end." (Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf. Munich 1938, p. 203); Propaganda has to “limit itself to a little and repeat this forever. Perseverance is (...) the first and most important requirement for success. ”(Adolf Hitler: Mein Kampf. Munich 1938, p. 202.)

- ↑ Reich Propaganda Leader of the NSDAP. The development of the office of Reich Propaganda Leader until the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure EHRI came to power , accessed on February 27, 2020.

- ↑ Albrecht Tyrell (ed.): "Führer befiehl ...". Testimonials from the time of the NSDAP's struggle. Documentation and Analysis, Düsseldorf 1969, pp. 255 ff.

- ↑ Goebbels writes exemplarily in his diary on September 4, 1932: “In an editorial I make sharp attacks against the 'noble people'. If we want to keep the party intact, we must now appeal again to the primitive mass instincts ”. Quoted in Ralf Georg Reuth (ed.): Joseph Goebbels Tagebücher , 2nd volume, Piper, Munich, p. 696.

- ↑ Reich Propaganda Leader of the NSDAP. The development of the office of Reich Propaganda Leader until the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure EHRI came to power , accessed on February 27, 2020.

- ↑ Josef Olbrich: Adult Education in the Time of National Socialism , in: History of Adult Education in Germany , VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2001, pp. 217–269.

- ↑ See Guido Knopp: Hitler's Helpers. Goldmann, Munich 1998.

- ^ Ernst Hanisch : History of Austria 1890-1990: The long shadow of the state. Vienna 1994.

- ^ Lutz Winckler: Study on the social function of fascist language. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1970.

- ↑ A summary of the socio-psychological mechanisms of the formation of enemy images can be found in Haim Omer et al. a. (Ed.): Enemy images - psychology of demonization. Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-49100-3 , pp. 42-65; there also "premises of a demonic view (...) 7. Healing consists in the eradication of the hidden evil".

- ↑ Guido Knopp : Hitler's helpers. Goldmann, Munich 1998.

- ↑ Stephan Marks: Why did they follow Hitler? The Psychology of National Socialism. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2007.

- ↑ Joachim C. Fest : Hitler. A biography. Frankfurt am Main 1973, p. 74 ff.

- ^ Rudolf Stöber: The nation seduced by success. Germany's public mood from 1866 to 1945. Steiner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07238-1 , p. 170.

- ↑ Military History Research Office : The German Reich and the Second World War . Volume I: The propaganda mobilization for the war. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, ISBN 3-421-01934-7 , p. 104.

- ^ Béla Grunberger, Pierre Dessuant: The anti-Semitism of Hitler. In: Béla Grunberger, Pierre Dessuant: Narcissism, Christianity, Anti-Semitism. A psychoanalytic investigation. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-608-91832-9 , p. 474.

- ↑ Grunberger, Dessuant: Narcissism, Christianity, Antisemitism. 2000, p. 474.

- ↑ Götz Aly : Hitler's People's State . Robbery, Race War and National Socialism. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-10-000420-5 , p. 49 ff.

- ↑ a b Götz Aly: Hitler's People's State. 2005, p. 11.

- ↑ cf. Kari Taskinen: National Socialist use of language in the war reports of Propaganda Company 680 from 1941 to 1944. A language-critical analysis of selected articles in the front newspaper “Lappland-Kurier” University of Tampere, 2013

- ↑ Joachim Zeller : Dresden 1938: "Here too is German land". In: Ulrich van der Heyden , Joachim Zeller (ed.): Colonialism in this country. A search for clues in Germany. Sutton, Erfurt 2007, ISBN 978-3-86680-269-8 , pp. 262–266, here pp. 263 f.

- ^ Reviews by Perlentaucher to the book Robert N. Proctor: Blitzkrieg against cancer: Health and Propaganda in the Third Reich. Klett-Cotta, 2002, ISBN 3-608-91031-X .

- ↑ Elke Frietsch: Kulturproblem Frau: Femininity Images in the Art of National Socialism. Böhlau-Verlag 2006, ISBN 3-412-35505-4 .

- ↑ Claudia Koonz: Mothers in the Fatherland. Women in the Third Reich. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Hamburg 1994.

- ↑ Wolfgang Duchkowitsch, Fritz Hausjell, Bernd Semrad (eds.) The spiral of silence: on dealing with National Socialist newspaper studies , including Peter Meier / Roger Blum: "Science rooted in Swiss soil" - On the history of journalism and newspaper studies in Switzerland 1945 , p. 167, LIT Verlag Wien, 2004 ISBN 3-8258-7278-5 .

- ^ Meyn, H: Mass media in Germany . Ed .: Konstanz. New edition 2004 edition. Constance, 2004, p. cape. 3.3 Third Reich .

- ↑ Michael Schornstheimer: Joseph Goebbels: Der Scharfmacher ( three-part documentation about Joseph Goebbels ( memento of October 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ Film in the Nazi state filmportal.de, May 8, 2013

- ^ Andreas Kötzing: National Socialist Propaganda: "Verbotene Films" Goethe-Institut , August 2014

- ↑ Michel Germany Special 2016 , Volume 1, Schwanenberger Verlag, pp. 1136 ff.