Reichstag election November 1932

The Reichstag election of November 6, 1932 was the election for the 7th German Reichstag . It had become necessary because Paul von Hindenburg had dissolved the Reichstag after a severe parliamentary defeat of the government under Franz von Papen . The election ended with a considerable loss of votes for the NSDAP . For a short time, the rise of the party seemed to have stopped. A parliamentary government was not possible, however, also because the extreme parties NSDAP and KPD still had a mathematical majority. After Kurt von Schleicher's brief reign , Adolf Hitler was made Chancellor of the Reich. The following elections on March 5, 1933 took place in the shadow of the beginning dictatorship.

prehistory

After the Reichstag election in July 1932 , the NSDAP was unable to form a government on a parliamentary basis because of the high profits of the NSDAP. There were various simulation games and considerations behind the scenes. There were real coalition negotiations in Prussia and in the Reich between the NSDAP and the Center Party . The driving forces were Joseph Joos from the workers' wing of the center and the Reich organization leader of the NSDAP Gregor Strasser . Hitler and Joseph Goebbels saw the negotiations primarily as a means of exerting pressure. Their goal was a presidential cabinet under Hitler's leadership. The negotiations between the center and the NSDAP ultimately failed.

The newly elected Reichstag met on August 30 for a constituent session under the leadership of the senior president Clara Zetkin (KPD). Zetkin gave an agitational opening speech, in which she expressed the hope, among other things, that she would soon open the first council congress of Soviet Germany as “senior president”. The most important item on the agenda was the election of the President of the Reichstag . According to parliamentary custom, this office was due to the NSDAP as the strongest parliamentary group. The center signaled that it would vote for Hermann Göring . The SPD and the KPD wanted to vote against this. With the votes of the center and the NSDAP, Göring was elected in the first ballot. Paul Löbe , the SPD candidate, was also defeated in the elections for vice president. The Presidium of the Reichstag was thus without a representative of the left-wing parties.

The presidential cabinet of Franz von Papen continued to rule without parliamentary support on the basis of the emergency ordinance law of the Reich President. On September 4th and 5th, the government issued emergency ordinances with a clear business-friendly orientation, for example in relation to the relaxation of collective bargaining law.

September crisis

The pressure on the Papen government became apparent during the only regular session of the 6th German Reichstag elected in the previous Reichstag elections on September 12, 1932. The only item on the agenda was the receipt of a government statement, but the communists requested the repeal of two emergency ordinances and a vote of no confidence in the Papen government. Nobody objected. The National Socialists suspended the session for half an hour to discuss things with Hitler and then supported the motion. This gave von Papen the time he needed to hurry to send a messenger to the Reich Chancellery , to date an order for dissolution (based on Article 25 of the Weimar Constitution) already signed by Reich President Paul von Hindenburg and to bring it back to the Reichstag.

With abuse and boos from the MPs, Papen now entered the Reichstag with the red folder under his arm and waved provocatively to the MPs with her. Hermann Göring reopened the meeting and immediately stated that the communist proposal would now be voted on. Von Papen asked in vain to speak, which according to the rules of procedure should normally have been given at any time. Goering deliberately looked to the left during the ongoing vote and "overlooked" the Chancellor. Papen thereupon placed the red liquidation order on Goering's desk and left the Reichstag with his ministers. With an overwhelming majority of 513 to 42 votes, the Reichstag finally repealed Papen's emergency ordinances. Only DNVP and DVP stood by the Reich government. Goering, however, pushed the portfolio aside as irrelevant, since it had been countersigned by men whom the Reichstag had just overthrown. However, since the order came into effect when Göring's desk was down and thus before the voting result was established, the dissolution of the Reichstag was legal and new elections were to be announced by November 6th at the latest. The Reichstag was dissolved on the grounds "... because there is a risk that the Reichstag will demand the repeal of my emergency decree of September 4th of this year."

Papen had suffered a heavy defeat, but remained in office. He delivered his government statement not in parliament, but on the radio that evening. In it he outlined the new state order he was planning. Formal democracy should be replaced by “impartial national governance”. The influence of the voters should essentially be limited to the election of the Reich President. Prussia and the Reich should be ruled together. Professional elements should have a strong role. Success in combating unemployment was critical to the survival of the Papen government. However, the creation of job creation measures failed to materialize.

Election campaign and results

The election campaign differed significantly from that of the spring of the year. If this was marked by unprecedented violent clashes, the ballot was now much less emotional. There were no particular highlights. Apparently in order to penetrate the supporters of the NSDAP, the KPD used nationalist arguments. The struggle against the SPD as the “social-fascist” main enemy was intensified again. Shortly before the election, the Berlin transport workers' strike led to a collaboration between the communist RGO and the National Socialist company cell organization .

In November 1932 there were 1.4 million fewer voters than in July 1932; thus the voter turnout fell from 84.1% to 80.6%. The NSDAP received 2 million votes less; their share sank from 37.3% to 33.1% and the number of their mandates from 230 to 196. The SPD lost 700,000 votes; their share of the vote fell from 21.6% to 20.4%. There were definitely gains. As in the last election, Rothenburg ob der Tauber was the constituency with the highest percentage of votes for the NSDAP with 76%. But now some constituencies in Upper Hesse came to comparable results.

The winners included the DNVP and the KPD. The DNVP was able to gain 781,000 votes. Their share of the vote rose to 8.3%. The KPD had 698,000 votes more than in July. This corresponded to a share of 16.9%. The two Catholic parties Zentrum and BVP recorded slight losses. The German State Party and the DVP remained insignificant without losing any further.

One reason for the lower voter turnout is electoral fatigue after the numerous previous elections. In the last election, the NSDAP was able to win over previous non-voters; this time it was different. Another factor was dissatisfaction with the parties elected so far, including the NSDAP.

From the good results of the DNVP, one can assume that some of the voters approved of the Papen government (supported by the DNVP). The government probably benefited from the first signs of economic recovery. Many middle-class and middle-class voters of the NSDAP were disappointed as a result of the merger with the KPD in the Berlin transport workers' strike, as well as the political violence. The political left, i.e. the SPD and KPD, were together again stronger than the NSDAP. As a result of the mutual mistrust and the accusation of social fascism, this played no role politically. There was a clear shift from the SPD to the KPD. The communists were now close to the SPD.

| Political party | be right | Votes in percent (change) | Seats in the Reichstag (change) | Seats in percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Socialist German Workers' Party - Hitler Movement (NSDAP) | 11,737,021 | 33.1% | −4.2% | 196 | −34 | 33.6% |

| Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) | 7,247,901 | 20.4% | −1.2% | 121 | −12 | 20.7% |

| Communist Party of Germany (KPD) | 5,980,239 | 16.9% | + 2.6% | 100 | +11 | 17.1% |

| German Center Party (Center) | 4,230,545 | 11.9% | −0.5% | 70 | −5 | 12.0% |

| German National People's Party (DNVP) | 2,959,053 | 8.3% | + 2.4% | 51 | +14 | 8.8% |

| Bavarian People's Party (BVP) | 1,094,597 | 3.1% | −0.1% | 20th | −2 | 3.4% |

| German People's Party (DVP) | 660.889 | 1.9% | + 0.7% | 11 | +4 | 1.9% |

| Christian Social People's Service (CSVD) | 403,666 | 1.1% | + 0.1% | 5 | +2 | 0.9% |

| German State Party (DStP) | 336,447 | 1.0% | ± 0 | 2 | −2 | 0.3% |

| German Farmers Party (DBP) | 149.026 | 0.4% | ± 0 | 3 | +1 | 0.5% |

| Wuerttemberg Farmers and Vineyards Association (Landbund) | 105.220 | 0.3% | ± 0 | 2 | ± 0 | 0.3% |

| Reich Party of the German Mittelstand (Economic Party ) | 110,309 | 0.3% | −0.1% | 1 | −1 | 0.2% |

| German-Hanoverian Party (DHP) | 63,966 | 0.2% | + 0.1% | 1 | +1 | 0.2% |

| Thuringian Federation | 60,062 | 0.2% | + 0.2% | 1 | +1 | 0.2% |

| Others | 391,846 | 1.1% | ± 0 | 0 | −2 | 0% |

| Total | 35,470,788 | 100.0% | 584 | −24 | 100.0% | |

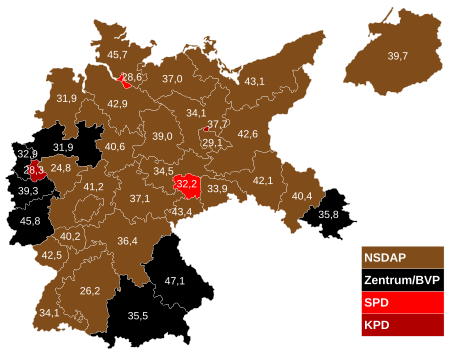

Parties with the highest number of votes by constituency (the percentage of the strongest party is given)

consequences

The forward headline after the election "Down with Hitler", similar to the headlines in civil leaves. The Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung saw the result as a “political warning to the National Socialists because the magic of irresistibility had been broken”. This is how the leadership of the NSDAP saw it. Goebbels spoke of a "failure" in his diary. The seemingly unstoppable rise of the National Socialists seemed to have stopped. On the economic level, there were slight signs of recovery and with it the hope of political de-radicalization.

Internally, the party had to contend with the power struggle between Hitler and Gregor Strasser . The donations from the industry and other circles flowed sparse and the party stood with a largely empty party coffers. With great effort and the exertion of all forces, it was possible to win the state elections in Lippe in 1933 with 39.5%, which the NSDAP exploited for propaganda throughout Germany.

If after the previous election there was still a mathematical possibility for a coalition between the NSDAP, BVP and the center, this was no longer available. This meant that a new parliamentary majority was temporarily excluded. The clearly anti-parliamentary parties KPD, NSDAP and DNVP together had a majority. It was to be expected that the new Reichstag would again express mistrust of the government as soon as possible and repeal emergency ordinances. Papen therefore suggested to Hindenburg a dissolution of parliament and the postponement of new elections, thus a temporary dictatorship. Kurt von Schleicher did not agree to this on behalf of the Reichswehr for fear of a civil war. Rather, he relied on winning the moderate wing of the NSDAP around Strasser to participate in the government and thus to split the party. He also believed that he could get the free trade unions on board. With this he wanted to bring about a government across all camps with a parliamentary majority, if possible. Hindenburg was convinced of this, dismissed Papen and assigned Schleicher to form a government. His cross-front concept failed due to the reluctance of the unions and the disempowerment of Strasser by Hitler. As an opponent of Schleicher, Papen approached Hitler and, supported by the camarilla around Hindenburg, succeeded in winning the Reich President for a Hitler-Papen government. On January 30, 1933, Hindenburg appointed Hitler Chancellor. The next Reichstag elections on March 5, 1933 took place under the conditions of Hitler's emerging dictatorship.

See also

- List of members of the Reichstag in the Weimar Republic (7th electoral term)

- List of constituencies and constituency associations of the Weimar Republic

- Papen's cabinet

- Schleicher's cabinet

- Cabinet Hitler

- Seizure of power

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ The German Empire. Reichstag election November 1932 Andreas Gonschior.

- ↑ The German Empire. Reichstag election July 1932 Andreas Gonschior.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The way into the disaster. Workers and the labor movement in the Weimar Republic 1930 to 1933. 2nd edition, Berlin and Bonn 1990, p. 721.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The way into the disaster. Workers and the labor movement in the Weimar Republic 1930 to 1933. 2nd edition, Berlin and Bonn 1990, p. 723.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The way into the disaster. Workers and the labor movement in the Weimar Republic 1930 to 1933. 2nd edition, Berlin and Bonn 1990, p. 723f.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The way into the disaster. Workers and the labor movement in the Weimar Republic 1930 to 1933. 2nd edition, Berlin and Bonn 1990, p. 726.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The long way to the west. German History 1806–1933 , Bonn 2002, pp. 511/522.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The way into the disaster. Workers and the labor movement in the Weimar Republic 1930 to 1933. 2nd edition, Berlin and Bonn 1990, pp. 730–733.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993, pp. 524f.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler : Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy . Beck, Munich 1993, pp. 532f.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993, p. 533f.

- ↑ Jürgen W. Falter: The elections of 1932/33 and the rise of the totalitarian parties , p. 277 ( online ( memento of the original from October 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. ).

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy . Beck, Munich 1993, p. 535 f.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993, p. 536.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy. Beck, Munich 1993, p. 536f.

- ↑ Jürgen W. Falter: The elections of 1932/33 and the rise of the totalitarian parties Online version ( Memento of the original from October 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , P. 277.

- ↑ Jürgen W. Falter: The elections of 1932/33 and the rise of the totalitarian parties Online version ( Memento of the original from October 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , P. 278.

- ↑ Jürgen W. Falter: The elections of 1932/33 and the rise of the totalitarian parties Online version ( Memento of the original from October 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , P. 278.

- ^ Ludger Grevelhörster: Brief history of the Weimar Republic. Münster, 2003, pp. 178-180.