Expropriation

The dispute over the expropriation of princes in the Weimar Republic was about the question of what should be done with the previously confiscated assets of the German royal houses , which had been politically disempowered in the course of the November revolution of 1918. These disputes began as early as the months of the revolution. They continued in the following years and became more intense through legal proceedings between individual royal houses and the respective countries of the German Empire , as the courts upheld the princes' claims for damages. Highlights of the conflict were the successful referendum in March 1926, and the failed referendum without compensation expropriation on 20 June 1926th

The popular initiative was initiated by the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Reluctantly, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) joined. Not only voters of the KPD and the SPD advocated expropriation without compensation. Many supporters of the German Center Party (Zentrum) and the German Democratic Party (DDP) also affirmed it. In certain regions of Germany, voters of conservative national parties also supported this legislative initiative. It was promised to distribute land to farmers, housing, support for war invalids and other social measures.

Aristocratic associations, the churches of the two major denominations, large agricultural and industrial interest groups as well as the parties and associations of the right-wing political camp stood up for the princes. By calling for a boycott they ultimately contributed to the failure of the referendum.

In the place of expropriation without compensation, there were individual severance agreements. They regulated the distribution of wealth between the respective countries and the former royal houses.

Events are interpreted differently in politics and history . For example, while the official historical studies of the GDR assessed the actions of the KPD at that time positively, West German historians draw attention to the considerable burdens that resulted from the plebiscite initiatives for the cooperation of the SPD with the republican parties of the bourgeoisie. In addition, reference is made to the generation conflicts that emerged in this political debate. Occasionally the campaign for expropriation without compensation is seen as a positive example of direct democracy .

Historical context and initiative

Development until the end of 1925

The November Revolution ended the rule of the ruling royal houses in Germany in 1918. These have been forced to resign , did so voluntarily, given the new overall political situation or were deposed against their will. Their property was confiscated , but - in contrast to the situation in German Austria - they were not immediately expropriated.

There were no confiscations at the imperial level because there were no corresponding property. That is why the empire renounced a nationwide uniform regulation and left it to the countries how they wanted to regulate the confiscations . In addition, the Council of People's Representatives feared that such expropriations would nourish the desires of the victorious powers, which could have made reparation claims on expropriated, former princely wealth .

The Weimar Constitution of 1919 guaranteed by Article 153 on the one hand the property . On the other hand, with this article she had opened up the possibility of expropriations if this served the common good . Such expropriation had to take place on a legal basis and the expropriated had to be compensated “appropriately” , unless a Reich law provided otherwise. Article 153 provided legal recourse for disputes.

The negotiations of the individual state governments with the royal houses dragged on due to different ideas about the amount of compensation. The negotiating parties also often struggled to clarify what the former ruling princes were entitled to as private property, in contrast to property to which they only had access in their capacity as sovereigns ( domain question ). With a view to Article 153 of the constitution, some royal houses also demanded the complete surrender of their previous property and compensation for lost property income. The situation was made more complicated by the continuing devaluation of money in the wake of inflation in Germany , which reduced the value of compensation payments. Individual royal houses therefore challenged the contracts that they had previously concluded with the contractual partners on the state side.

The economic significance of the objects in dispute was considerable. In particular, the existence of the small countries depended on whether they succeeded in winning the essential parts of their wealth. In Mecklenburg-Strelitz, for example, the disputed lands alone accounted for 55 percent of the national territory. In other smaller Free States this proportion was at least 20 to 30 percent. In large states such as Prussia or Bavaria, however , the percentage of disputed land areas was hardly significant. The absolute numbers there reached dimensions that could approach the size of duchies elsewhere. The demands that the royal houses made on the individual countries added up to a total of 2.6 billion marks.

In judicial disputes, the predominantly conservative and monarchist judges repeatedly decided in favor of the royal houses. A ruling by the Reichsgericht dated June 18, 1925 , caused public displeasure . It repealed a law that the USPD- dominated state assembly of Saxony-Gotha on July 31, 1919 for the purpose of confiscating the entire domain property of the Dukes of Saxony- Coburg and Gotha had issued. This state law was not constitutional in the eyes of the judges. They reassigned the entire land and forest property to the Princely House. The total value of this judicially returned property was 37.2 million gold marks. Head of the Princely House at that time was Carl Eduard Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha , a declared opponent of the republic.

Prussia also negotiated for a long time with the House of Hohenzollern . A first attempt at unification failed in 1920 due to resistance from the Social Democratic parliamentary group, and the Hohenzollern opposed a second in 1924. The Prussian Ministry of Finance presented a new draft contract on October 12, 1925, which was heavily criticized in public because it was intended to return around three quarters of the disputed property to the Princely House. Not only the SPD opposed this comparison , but also the DDP, which turned against its own finance minister, Hermann Höpker-Aschoff . In this situation, the DDP submitted a bill to the Reichstag on November 23, 1925. This should authorize the states to pass state laws to regulate property disputes in the disputes with the former royal houses. Legal recourse against the content of these state laws should be expressly excluded. The SPD had few objections to the DDP's draft law, as it had itself developed a very similar draft law in 1923.

Initiative for a referendum

Two days later, on November 25, 1925, the KPD also initiated a bill. This did not provide for a balance of interests between the states and the princely houses, but an expropriation without compensation. The lands were to be passed on to farmers and tenants, castles were to be converted into convalescent homes or to alleviate the housing shortage, and the cash should ultimately go to war invalids and survivors.

The addressee of this draft law was not so much the Reichstag, where such a proposal would hardly find the necessary majority, but the people. By means of a referendum, it was supposed to express its will for a radical change in property relations - initially with reference to the seized princely property.

The communists were aware that such a legislative initiative was attractive at a time when the unemployment rate was rising, mainly due to the significant economic downturn since November 1925 and also to the so-called rationalization crisis . In addition, hyperinflation was freshly remembered. It had shown the special value of immovable assets that were waiting for distribution here. In the spirit of a united front policy , the KPD initiative aimed to win back lost voters and possibly also to address members of the middle classes who were among the losers in inflation. As an expression of such a strategy, on December 2, 1925, the KPD invited the SPD, the General German Trade Union Federation (ADGB), the AfA-Bund , the German Civil Service Federation , the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold and the Red Front Fighters Federation together To initiate a referendum.

At first, the SPD reacted negatively. The KPD's endeavor to drive a wedge between the social democratic “masses” and the SPD executives, who are dubbed “bigwigs”, seemed all too obvious to her. A referendum and referendum was also warned against the parliamentary coloring. Furthermore, the leadership of the SPD saw opportunities to resolve the issues in parliament. Another reason for reserves in relation to the plebiscite initiative was its impending failure. More than half of all eligible voters in Germany, i.e. almost 20 million voters, had to approve a corresponding referendum if the law in question changed the constitution. In the previous Reichstag elections on December 7, 1924, however, the KPD and SPD only received around 10.6 million votes.

After the turn of the year 1925/26, the mood within the SPD changed. Talks about the admission of Social Democrats to the Reich government finally failed in January, so that from now on the SPD was able to concentrate more on opposition politics. For this reason, too, another draft law that had been drawn up in the Luther cabinet was rejected . This draft, which was finally presented on February 2, provided for the dispute to be postponed to a new legal level. Under the chairmanship of the President of the Reich Court, Walter Simons , a special court was to be exclusively responsible for property disputes. There were no plans to revise treaties that had already been concluded between states and former princes. Compared to the parliamentary initiative of the DDP of November 1925, this was a development that was friendly to the princes. These factors were important for the top of the SPD, but of secondary importance - the decisive reason for the change in mood in the SPD leadership was a different one: there was clear support for the KPD's legislative initiative at the base of the SPD. The party leadership now feared a considerable loss of influence, membership and voters if they ignored this mood.

On January 19, 1926, the chairman of the KPD, Ernst Thälmann , called on the SPD to participate in the so-called Kuczynski Committee. This committee formed ad hoc in mid-December 1925 from the circle of the German Peace Society and the German League for Human Rights was named after the statistician Robert René Kuczynski and prepared a referendum on the expropriation of the princes. About 40 different pacifist, left and communist groups belonged to it. Within this committee, the KPD and its support organizations had the greatest importance. On January 19, the SPD rejected the KPD's proposal to join the Kuczynski Committee and instead asked the ADGB to mediate. These should be conducted with the aim of submitting a bill to the people in a referendum for the expropriation of princes, backed by the largest possible group of political supporters. The ADGB complied with this request. The talks he moderated between the KPD, the SPD and the Kuczynski Committee began on January 20, 1926. Three days later, a joint bill was agreed. This envisaged the expropriation of the former princes and their family members without compensation "for the common good". On January 25, the draft law was sent to the Reich Ministry of the Interior with the request that a date for a referendum be set as quickly as possible. The ministry set the implementation of the referendum for the period from March 4 to 17, 1926.

Until then, the communists' united front tactic was only technically possible - the SPD and KPD had drawn up an agreement on the production and distribution of drawing lists and posters. The SPD still strongly opposed a united political front. It was important to her that all agitation events for the referendum should be carried out on her own, and in no case jointly with the KPD. Local SPD associations were warned or reprimanded of such advances by the KPD if such offers were accepted. The ADGB also publicly stated that there was no united front with the communists.

In addition to the workers' parties, the ADGB, the Red Front Fighters Association and some personalities, such as Albert Einstein , Käthe Kollwitz , John Heartfield and Kurt Tucholsky, campaigned for the referendum. The bourgeois parties, the Reichslandbund and a large number of "national" associations as well as the churches appeared as opponents of the project with varying degrees of commitment .

Result of the referendum

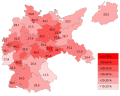

The referendum "Expropriation of the princely property" carried out in the first half of March 1926 underscored the ability of the two workers' parties to mobilize. Of the 39.4 million eligible voters, 12.5 million signed the official lists. The request exceeded the quorum of 10 percent of the electorate more than three times. The number of votes that the KPD and SPD had achieved in the Reichstag elections in December 1924 was exceeded by almost 18 percent with the referendum. The strong support in strongholds of the center was particularly noticeable. The number of supporters of the referendum was significantly higher than the total number of votes for the KPD and SPD in the last Reichstag election. Similar tendencies were also evident in domains of liberalism, for example in Württemberg. The corresponding gains recorded in large cities were particularly clear. Not only supporters of the workers' parties, but many voters from the bourgeois and right-wing parties there advocated expropriation without compensation.

In rural regions, on the other hand, there was often strong resistance to the plebiscite. In East Elbe in particular , the KPD and SPD were unable to achieve their results in the last Reichstag election. Administrative obstacles to the referendum and threats by large agricultural employers to their employees had their effect here. In Bavaria, particularly in Lower Bavaria , participation in the referendum was similarly below average. Bavaria had the second lowest participation after the dwarf state of Waldeck . The Bavarian People's Party (BVP) and the Catholic Church strongly and successfully advised against participating in the referendum. In addition, a largely undisputed agreement with the Wittelsbach family was achieved in Bavaria in 1923 with the Wittelsbach Compensation Fund.

Decision and consequences

Preparation and result of the referendum

| Statements by parties or social groups on the plebiscites |

|---|

|

DNVP “If the principle that property is sacred is broken only with the cowardly raid on the property of the defenseless princes, then general socialization, the general expropriation of all private property will soon follow, regardless of whether it is a large factory or a carpenter's workshop whether it is a huge department store or a greenery store, whether it is a manor or a suburban garden, whether it is a large bank or a worker's savings book. " The Kreuzzeitung , politically close to the DNVP, wrote: “After the princely property, it will be another turn. Because the Jewish disintegration spirit of Bolshevism knows no boundaries ”. |

|

BVP The referendum is an "intrusion of Bolshevik aspirations" into the state and society. The expropriation project is viewed as a “serious violation of the moral imperative to protect private property.” Furthermore, the referendum was an inadmissible interference in the internal affairs of Bavaria, which had already been agreed with the Wittelsbachers. This would amount to a “rape of the Bavarian people”. |

|

Catholic Church The Catholic clergy, united in the Fulda and Freising Bishops' Conference , saw in the expropriation project a "confusion of moral principles" that must be countered. The conception of property that emerges was "incompatible with the principles of Christian moral law". Property is to be protected because it is "based on the natural moral order and protected by God's commandment". The Bishop of Passau, Sigismund Felix von Ow-Felldorf , expressed himself more drastically . Participation in the referendum is "a serious sin against God's 7th commandment". He called on those who had supported the referendum to withdraw their signature. |

|

Protestant church The Church Senate of the Evangelical Church of the Old Prussian Union, as the governing body of by far the largest regional church in the German Reich, avoided the stimulus word "princes" in its statement. His warning was nevertheless clear: "Loyalty and faith will be shaken, the foundations of an orderly state undermined if individual people's entire property is to be taken away without compensation." The German Evangelical Church Committee, the highest organ of the German Evangelical Church Federation , rejected the expropriation project. "The requested expropriation without compensation means the disenfranchisement of German national comrades and contradicts clear and unambiguous principles of the gospel." |

|

SPD June 20 is the day on which the "decisive battle [...] between democratic Germany and the powers of the past, which is once again rising," will take place. “It's about the future of the German republic. It is a question of whether the political power embodied in the state should be an instrument of rule in the hands of a social upper class or an instrument of liberation in the hands of the working masses. " |

|

KPD She saw the campaign for the expropriation of princes without compensation as a first step on the way to a revolutionary upheaval in society. In this sense, the Central Committee of the KPD said: "The hatred of the crowned robbers is the class hatred of capitalism and its slave system!" The KPD MP Daniel Greiner said in the Hessian state parliament on March 5, 1926: “You know that if the princes' private fortunes are touched, then it is not far to the next step, namely to acquire private property at all. It would be a blessing if it finally got that far ”. At another point the communist propaganda asked: "Russia gave five grams of lead to its princes, what does Germany give to its princes?" |

On May 6, 1926, the Reichstag passed a bill on the expropriation of the princes without compensation. It failed because of its bourgeois majority. Only if this draft had been adopted without changes would a referendum have been dropped. Now it has been scheduled for June 20, 1926.

Reich President Paul von Hindenburg had already set up a new hurdle on March 15, which should make the referendum more difficult. On this day, he informed Reich Justice Minister Wilhelm Marx that, in his view, the expropriations sought did not serve the general public, but rather represent nothing other than property evasion for political reasons. That is not provided for in the constitution. The Government Luther II confirmed on 24 April 1926 expressly the legal opinion of the president. For this reason, a simple majority was not enough for the referendum to be successful. Rather, 50 percent of those entitled to vote now had to agree, i.e. around 20 million voters.

Because it was to be expected that this number would not be reached, the government and the Reichstag prepared for further parliamentary negotiations on this issue. These discussions were also burdened by the reference to the constitutional character of the corresponding legal regulations, because in parliamentary expropriations were now only enforceable with a two-thirds majority. Only a law to which parts of the SPD on the political left and parts of the German National People's Party (DNVP) could agree would have been promising.

It was to be expected that the number of those who would support the expropriation of the princes without compensation on June 20, 1926, would increase again. There were a number of reasons for this assumption: Because the vote in June would be the decisive one, it was to be assumed that the mobilization of left voters would be even more successful than in March at the referendum. The failure of all previous parliamentary compromise attempts had also raised the voices of those in the bourgeois parties who also advocated such a radical change in princely ownership. For example, youth organizations from the center and the DDP demanded a “yes” vote. The DDP was divided into supporters and opponents of the referendum. The party leadership gave the DDP supporters free to choose which side they would take. Associations that represented the interests of those affected by inflation have meanwhile also called for approval of the referendum.

Two further factors put the opponents of the referendum, who had come together on April 15, 1926 under the umbrella of the "Working Committee against the Referendum", under additional pressure; Similar to the referendum, these opponents included associations and parties of the right, agricultural and industrial interest groups, the churches and the Association of German Court Chambers - i.e. the interest group of former federal princes. On the one hand, the apartment of Heinrich Claß , the leader of the Pan-German Association , had been searched at the behest of the Prussian Ministry of the Interior. Extensive coup plans were uncovered. Such searches also yielded comparable evidence in people from his group of employees. On the other hand, excerpts from a letter were published on June 7, 1926, which von Hindenburg had sent on May 22, 1926 to the President of the Reich Citizens' Council , Friedrich Wilhelm von Loebell . In this letter, von Hindenburg described the plebiscite as a “great injustice”, which shows a “regrettable lack of sense of tradition” and “gross ingratitude”. It violates "the fundamentals of morality and law". Von Hindenburg tolerated the use of his negative words on posters by those opposed to expropriation. He thus exposed himself to the suspicion that he was not above the parties and interest groups, but that he was openly switching to the conservative camp.

Against this background, the opponents of expropriation increased their efforts. The main message of their agitation was the assertion that the proponents of the referendum are not only concerned with the expropriation of princely property. Rather, they would simply intend the abolition of private property. The opponents accordingly called for a boycott of the referendum. From their point of view, this made sense because every abstention (like every invalid vote) had the same weight as a no. By calling for a boycott, the secret voting practically turned into an open one.

Significant financial resources were mobilized by the opponents of the referendum. For example, the DNVP used funds to agitate against the referendum, the sum of which was significantly higher than that for the 1924 election campaigns. Less money was also spent in the 1928 Reichstag election . The money for the agitation against the referendum came from contributions from royal houses, from industrialists and other donations.

Once again, East Elbe farm workers in particular were threatened with economic and personal sanctions if they took part in the referendum. One tried to scare small farmers by claiming that it was not only about the expropriation of the princely property, but also about the expropriation of cattle, facilities and land of every small farm. In addition, the opponents organized free beer festivals in some places on June 20, 1926 in order to keep voters away from the vote.

The National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) intensified the demagogic dimension on the political right by demanding the expropriation of Eastern Jews who had immigrated since August 1, 1914 instead of the expropriation of the princes . Initially, the left wing of the NSDAP around Gregor Strasser wanted the National Socialists to participate in the campaign to expropriate princes. Adolf Hitler rejected this demand at the Bamberg Führer Conference in mid-February 1926. Alluding to the imperial words of August 1914, he said: "For us today there are no princes, only Germans."

Of the approximately 39.7 million eligible voters, almost 15.6 million (39.3 percent) cast their vote on June 20, 1926. About 14.5 million voted “Yes”, and about 0.59 million voted “No”. Around 0.56 million votes were invalid. The referendum had thus failed, because in the meantime the Reich government, following a request by the Reich President, had declared the law to be constitutional. Not a relative , but an absolute majority would have been necessary for the referendum to be successful. This quorum of approval by at least 50% of those eligible to vote was only achieved in three of the 35 electoral districts throughout the Reich (in Berlin, Hamburg and Leipzig).

The referendum in favor of expropriation without compensation was again approved in the center's strongholds. The same applied to metropolitan voting districts. There is evidence that sections of the electorate who traditionally voted in a bourgeois, national and conservative manner were increasingly addressed. Although there were in some cases significantly more votes in favor than in the referendum, approval in agricultural parts of the country (especially eastern Elbe) was again below average. The participation rate in Bavaria was also low this time compared to other regions, despite the overall increase in participation there too.

Further treatment of the question of expropriation

A lasting trend to the left was not associated with this result, although this was feared by some opponents of expropriation without compensation and hoped for by parts of the SPD and the KPD. Many traditional DNVP voters, for example, only voted for the referendum because they were responding to the DNVP's broken election promise of 1924 to receive adequate compensation for inflationary damage. The ongoing ideological conflicts between the SPD and the KPD were also not overcome by the joint campaign for the referendum and referendum. As early as June 22, 1926, Die Rote Fahne , the party newspaper of the KPD, had claimed that the social democratic leaders had deliberately thwarted the success of the decision. Four days later, the Central Committee of the KPD said that the Social Democrats were now secretly promoting the "shameless prince robbery".

This assertion meant the willingness of the SPD to continue looking for a legal solution to the issue in the Reichstag. For two reasons, the SPD calculated that there would be considerable opportunities to participate in a regulation under Reich law, even if such a law required a two-thirds majority. On the one hand, she interpreted the referendum as clear support for social democratic positions. On the other hand, the minority government under Wilhelm Marx flirted with the admission of the SPD into the government, i.e. with the formation of a grand coalition, which would make it necessary to respond to social democratic demands in advance. The social democratic requests for changes to the government bill on the compensation for the prince were rejected after lengthy negotiations: There should be no strengthening of the lay element at the planned new Reich special court ; the SPD proposal that the judges of this court should be elected by the Reichstag was also not enforceable; the resumption of property disputes that had already been concluded and which had turned out unfavorably for the federal states was also not intended.

On July 1, 1926, the parliamentary group leadership of the SPD tried to convince the Reichstag parliamentary group of the SPD to accept the bill, which was due to be voted on the following day in the Reichstag. The group refused, however. This price for admission to a new Reich government was too high for the parliamentary group majority. She was also not convinced by the pressing arguments of the Prussian government under Otto Braun and the votes from the social democratic faction of the Prussian state parliament, who also wanted a Reich law to be able to conclude the dispute with the Hohenzollern on this basis.

On July 2, 1926, the factions of the SPD on the one hand and the DNVP on the other hand justified their no to the bill. As a result, no further decision was made on this bill - the government withdrew it.

From now on, agreements with the royal houses in the federal states had to be finally sought by direct negotiation. The position of the states was secured by a so-called blocking law until the end of June 1927, which prevented attempts by the royal houses to enforce claims against the states by means of civil actions. In Prussia, the desired agreement was reached on October 6, 1926 - a corresponding draft contract was signed by the State of Prussia and the General Plenipotentiary of the Hohenzollern, Friedrich von Berg . Approx. 250,000 acres of land fell to Prussia from the confiscated total assets, and approx . 383,000 acres remained at the Princely House, including all the branches. Prussia also took ownership of a large number of castles and a few other assets. From the point of view of the state government, this comparison was more favorable than the one that was planned for October 1925. The SPD parliamentary group abstained on October 15, 1926, although the majority of the parliamentary group internally rejected the treaty. The spending on the Hohenzollern family went too far for her. In the plenary session, however, the SPD did not seem to need an open “no”, because Otto Braun had threatened to resign in this case. When the SPD parliamentary group withdrew to abstain, the way was clear for the ratification of the treaty by the Prussian state parliament . Even the KPD could no longer block the way to this parliamentary approval, although it had caused tumultuous scenes in the plenum during the second reading on October 12, 1926.

Even before the legal settlement between Prussia and the Hohenzollerns, most disputes between states and princely houses had been settled amicably. After October 1926, however, the states of Thuringia , Hesse , Mecklenburg-Schwerin , Mecklenburg-Strelitz and, above all, Lippe still quarreled with the former royal houses . In some cases, the negotiations continued for many years. A total of 26 contracts to regulate property disputes between the states and the royal houses have been concluded. Through these contracts, the so-called burden objects usually went to the state. This included castles, buildings and gardens. Income objects, such as forests or valuable land, were predominantly assigned to the princely houses. In many cases, collections, theaters, museums, libraries and archives were incorporated into newly established foundations. In addition, on the basis of these contracts, the state often took over the court officials and servants as well as the associated supply burdens. Apanages and the so-called civil lists , that is, the part of the budget that had once been declared for the head of state and his court, were generally dropped in exchange for one-off compensation payments.

During the time of the presidential cabinets , there were several attempts in the Reichstag by both the KPD and the SPD to revive the question of the expropriation of the princes or the reduction of the prince's compensation. They should be a political reaction to the extensive trend towards wage and salary cuts in these years. However, none of these initiatives generated greater political attention. The KPD motions were flatly rejected by the other parties. SPD proposals were referred to the legal committee at best. There they silted up, partly because the Reichstag was repeatedly dissolved prematurely.

The Nazi state created after initial hesitation on February 1, 1939 by law the opportunity to intervene in dispute ended contracts. On the whole, however, this legal instrument was a preventive and threatening instrument, rather than a legal instrument. Claims by royal houses against the state, which had occasionally been made in the first years of the Third Reich , were intended to defend themselves with this "law on property disputes between the states and the formerly ruling royal houses". The threat of completely reorganizing the financial situation in favor of the Nazi state as a countermeasure against princely lawsuits should suppress all corresponding complaints and lawsuits from the princely side. It was not intended to bring the contractual situation into line.

Judgment of the Historians

History of the GDR

The Marxist-Leninist historiography of the GDR interpreted the expropriation of princes and the actions of the workers' parties essentially from a perspective that coincided with that of the KPD at the time. The KPD's united front strategy was interpreted as the right step in the class struggle. The plebiscitary actions were "the most powerful unitary action of the German working class in the period of the relative stabilization of capitalism". The SPD leadership and also the leadership of the free trade unions were attacked, especially when they were looking for a compromise with the bourgeois parties. The "attitude of the leaders of the SPD and the ADGB made the development of the popular movement against the princes much more difficult."

Non-Marxist historian

With his habilitation thesis from 1985, Otmar Jung presented the most extensive study of the expropriation of princes to date. In the first part, he analyzes the historical, economic and legal aspects of all property disputes for each individual country of the German Empire. This consideration includes around 500 pages of the more than 1200-page font. With this approach, Jung wants to prevent the danger of prematurely identifying the Prussian solution as the typical one. In the second part of the text, Jung traces the course of events in detail. His intention is to show that the lack of elements of direct democracy in the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany cannot be justified with “bad experiences” from the Weimar Republic, although this often happened. On closer inspection, the Weimar experience is different. According to Jung, the people's legislative initiative of 1926 was a welcome attempt to supplement parliamentarism where it was apparently incapable of resolving the problem - on the question of the clear and final division of property between the state and former princes. Here the referendum was a legitimate problem-solving process with a protest character. According to Jung, one of the results of the campaign for the expropriation of princes was that it discovered technical deficiencies in the people's legislative process itself, among other things because abstentions and no votes had exactly the same effect. With the correction of current judgments about plebiscitary elements of the Weimar Republic, Jung wants to pave the way to be able to discuss elements of direct democracy in the present without prejudice.

Thomas Kluck examines the attitude of German Protestantism. He makes it clear that the majority of theologians and publicists of the Evangelical Churches rejected the expropriation of princes. This was often justified with recourse to Christian commandments. In many cases, a backward-looking longing for the apparently harmonious times of the empire or the desire for a new, strong leadership was formulated in the negative statements . Kluck works out that contemporary conflicts, which included the dispute over the wealth of the former ruling princes, were often interpreted demonologically by German Protestantism : Behind these conflicts were seen the machinations of the devil, who wanted to tempt people to sin. In addition to the devil as a misanthropic "wire puller", the national conservative part of Protestantism branded Jews as the cause and beneficiary of political conflicts. Such an attitude of mind was wide open to the ideology of National Socialism and gave it, as it were, theological ordinations. This “ideological legwork” is “a piece of Protestant guilt history”.

Ulrich Schüren emphasizes that in 1918 the question of the expropriation of the princes, legitimized by revolutionary violence, could have been solved without major problems. In this respect, there was a failure of the November Revolution. Despite the failure, the later referendum had a significant indirect effect. After June 20, 1926, the plebiscite initiative increased the willingness to compromise in the conflict between Prussia and the House of Hohenzollern, so that a contractual agreement was reached between these parties in October. Stoking also makes it clear that the prince expropriation campaign showed tangible erosion tendencies in bourgeois parties. This particularly affected the DDP and DNVP, but also the center. Schüren suspects that the decreasing binding force of these bourgeois parties contributed to the rise of National Socialism after 1930.

A key issue in the assessment by non-Marxist historians is the question of the extent to which the plebiscitary disputes have burdened the Weimar compromise between the moderate labor movement and the moderate bourgeoisie. In this context, the policy of the SPD comes into focus. Peter Longerich states that the relative success of the referendum could not have been implemented for the SPD. In his opinion, the plebiscite also made it more difficult for the SPD to work with the bourgeois parties. Heinrich August Winkler draws this line of interpretation most vigorously. It is understandable that the SPD leadership supported the plebiscite in order not to lose ties to the social democratic base. However, the price was very high. After June 20, 1926, the SPD had found it difficult "to return to the familiar path of class compromise." The dispute over the expropriation of princes without compensation had shown the SPD's dilemma in the Weimar Republic. If she showed herself to be willing to compromise with the bourgeois parties, she ran the risk of losing supporters and voters to the KPD. If it emphasized class standpoints and found itself ready to form partial alliances with the KPD, it alienated the moderate bourgeois parties and tolerated that they looked for allies on the right edge of the party spectrum who had little interest in the continued existence of the republic. The plebiscites would not have strengthened confidence in the power of parliamentarism, but weakened it. They would also have aroused expectations that could hardly be met in practice. In Winkler's view, the resulting frustrations could only have a destabilizing effect on representative democracy . This assessment by Winkler clearly differs from Otmar Jung's position.

Hans Mommsen , on the other hand, draws attention to conflicts of mentality and generations in the republic. In his opinion, the plebiscites of 1926 revealed considerable differences in mentality and deep rifts between the generations in Germany. A large part, perhaps even the majority of Germans, were on the side of the republic proponents on this question, who protested with the plebiscites against the "backward-looking loyalty of the bourgeois ruling class". Mommsen also draws attention to the mobilization of anti-Bolshevik and anti-Semitic sentiments by the opponents of expropriation without compensation. This mobilization was an anticipation of the constellation "in which the remnants of the parliamentary system were to be smashed since 1931".

attachment

Results of the referendum and referendum by constituency

The following are the entries in the referendum and the results of the referendum by constituency .

Referendum

The quorum of 10% of the electorate was exceeded in all constituencies except Lower Bavaria.

| No. | Constituency | electoral legitimate |

Entries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | in % | |||

| 1 | East Prussia | 1,318,663 | 166.078 | 12.6 |

| 2 | Berlin | 1,467,237 | 864,362 | 58.9 |

| 3 | Potsdam II | 1,181,582 | 514.067 | 43.5 |

| 4th | Potsdam I. | 1,175,429 | 479.491 | 40.8 |

| 5 | Frankfurt / Oder | 1,038,777 | 244,600 | 23.5 |

| 6th | Pomerania | 1,148,014 | 204.715 | 17.8 |

| 7th | Wroclaw | 1,197,512 | 383,561 | 32.0 |

| 8th | Liegnitz | 769.460 | 267,415 | 34.8 |

| 9 | Opole | 791.982 | 153.038 | 19.3 |

| 10 | Magdeburg | 1,067,648 | 377.452 | 35.4 |

| 11 | Merseburg | 896.104 | 307.266 | 34.3 |

| 12 | Thuringia | 1,411,556 | 561,530 | 39.8 |

| 13 | Schleswig-Holstein | 1,005,640 | 296,073 | 29.4 |

| 14th | Weser-Ems | 901.857 | 201.228 | 22.3 |

| 15th | East Hanover | 652.674 | 152,647 | 23.4 |

| 16 | South Hanover-Braunschweig | 1,256,015 | 441.067 | 35.1 |

| 17th | Westphalia North | 1,334,136 | 358.081 | 26.8 |

| 18th | Westphalia-South | 1,648,767 | 580,807 | 35.2 |

| 19th | Hessen-Nassau | 1,571,165 | 538.098 | 34.2 |

| 20th | Cologne-Aachen | 1,352,900 | 366,540 | 27.1 |

| 21st | Koblenz-Trier | 749.247 | 118,723 | 15.8 |

| 22nd | Düsseldorf-East | 1,370,820 | 533.996 | 39.0 |

| 23 | Düsseldorf-West | 1,054,943 | 259,427 | 24.6 |

| 24 | Upper Bavaria-Swabia | 1,537,258 | 209.071 | 13.6 |

| 25th | Lower Bavaria | 783.207 | 61,822 | 7.9 |

| 26th | Francs | 1,563,624 | 321.760 | 20.6 |

| 27 | Palatinate | 563,743 | 158,892 | 28.2 |

| 28 | Dresden-Bautzen | 1,229,105 | 545.864 | 44.4 |

| 29 | Leipzig | 863,808 | 418.047 | 48.4 |

| 30th | Chemnitz-Zwickau | 1,168,670 | 577.155 | 49.4 |

| 31 | Württemberg | 1,631,808 | 478.034 | 29.3 |

| 32 | to bathe | 1,442,607 | 500,238 | 34.7 |

| 33 | Hessen-Darmstadt | 867.526 | 325,609 | 37.5 |

| 34 | Hamburg | 834.702 | 395.836 | 47.4 |

| 35 | Mecklenburg | 573,431 | 161.160 | 28.1 |

| German Empire as a whole | 39,421,617 | 12,523,750 | 31.8 | |

Referendum

| No. | Constituency | electoral legitimate |

voter turnout | Valid votes |

Invalid votes | Yes votes | No votes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | in % | number | in % | number | in% of the Electoral legitimate |

in% of voters |

|||||

| 1 | East Prussia | 1,306,978 | 279.372 | 21.4 | 274,330 | 5,042 | 1.8 | 264,576 | 20.2 | 96.4 | 9,754 |

| 2 | Berlin | 1,511,505 | 1,018,896 | 67.4 | 973.731 | 45.165 | 4.4 | 942,654 | 62.4 | 96.8 | 31,077 |

| 3 | Potsdam II | 1,215,329 | 636,647 | 52.4 | 611,396 | 25,251 | 4.0 | 589.712 | 48.5 | 96.5 | 21,684 |

| 4th | Potsdam I. | 1,198,266 | 614,526 | 51.3 | 588,835 | 25,691 | 4.2 | 566,822 | 47.3 | 96.3 | 22,013 |

| 5 | Frankfurt / Oder | 1,037,039 | 323.941 | 31.2 | 310,952 | 12,989 | 4.0 | 297,532 | 28.7 | 95.7 | 13,420 |

| 6th | Pomerania | 1,145,648 | 286,862 | 25.0 | 281.081 | 5,781 | 2.0 | 269,406 | 23.5 | 95.8 | 11,675 |

| 7th | Wroclaw | 1,202,437 | 421.194 | 35.0 | 407.737 | 13,457 | 3.2 | 383.226 | 31.9 | 94.0 | 24,511 |

| 8th | Liegnitz | 769,447 | 287.903 | 37.4 | 276,564 | 11,339 | 3.9 | 263.149 | 34.2 | 95.1 | 13,415 |

| 9 | Opole | 794.492 | 210.730 | 26.5 | 205.835 | 4,895 | 2.3 | 193,855 | 24.4 | 94.2 | 11,980 |

| 10 | Magdeburg | 1,068,561 | 493,672 | 46.2 | 470.508 | 23.164 | 4.7 | 453.811 | 42.5 | 96.5 | 16,697 |

| 11 | Merseburg | 892.105 | 378.123 | 42.4 | 363,804 | 14,319 | 3.8 | 351.232 | 39.4 | 96.5 | 12,572 |

| 12 | Thuringia | 1,422,590 | 638.497 | 44.9 | 607.420 | 31,077 | 4.9 | 582.502 | 40.9 | 95.9 | 24,918 |

| 13 | Schleswig-Holstein | 1,013,975 | 382.701 | 37.7 | 366.725 | 15,976 | 4.2 | 353.005 | 34.8 | 96.3 | 13,720 |

| 14th | Weser-Ems | 911.161 | 279,327 | 30.7 | 266,841 | 12,486 | 4.5 | 255.941 | 28.1 | 95.9 | 10,900 |

| 15th | East Hanover | 656.665 | 199,731 | 30.4 | 189,911 | 9,820 | 4.9 | 180.403 | 27.5 | 95.0 | 9,508 |

| 16 | South Hanover-Braunschweig | 1,264,919 | 532.084 | 42.1 | 503.928 | 28,156 | 5.3 | 479,895 | 37.9 | 95.2 | 24,033 |

| 17th | Westphalen-North | 1,358,093 | 483.227 | 35.6 | 465.670 | 17,557 | 3.6 | 448.079 | 33.0 | 96.2 | 17,591 |

| 18th | Westphalen-South | 1,645,182 | 777.206 | 47.2 | 750.982 | 26,224 | 3.4 | 727.725 | 44.2 | 96.9 | 23,257 |

| 19th | Hessen-Nassau | 1,594,919 | 682.980 | 42.8 | 659.748 | 23,232 | 3.4 | 635.511 | 39.8 | 96.3 | 24,237 |

| 20th | Cologne-Aachen | 1,364,750 | 495.705 | 36.3 | 486,628 | 9,077 | 1.8 | 465.923 | 34.1 | 95.7 | 20,705 |

| 21st | Koblenz-Trier | 756.640 | 145,100 | 19.2 | 142.131 | 2,969 | 2.0 | 134,988 | 17.8 | 95.0 | 7.143 |

| 22nd | Düsseldorf-East | 1,402,520 | 620.609 | 44.2 | 603,696 | 16,913 | 2.7 | 585.496 | 41.7 | 97.0 | 18,200 |

| 23 | Düsseldorf-West | 1,067,785 | 379.664 | 35.6 | 372.461 | 7,203 | 1.9 | 359.833 | 33.7 | 96.6 | 12,628 |

| 24 | Upper Bavaria-Swabia | 1,550,778 | 334,607 | 21.6 | 330,489 | 4.118 | 1.2 | 319,886 | 20.6 | 96.8 | 10,603 |

| 25th | Lower Bavaria | 779.332 | 102.963 | 13.2 | 101,392 | 1,571 | 1.5 | 97,303 | 12.5 | 96.0 | 4,089 |

| 26th | Francs | 1,566,278 | 441.406 | 28.2 | 431.163 | 10,243 | 2.3 | 416,666 | 26.6 | 96.6 | 14,497 |

| 27 | Palatinate | 567.016 | 195,407 | 34.5 | 191,528 | 3,879 | 2.0 | 185.113 | 32.6 | 96.7 | 6,415 |

| 28 | Dresden-Bautzen | 1,250,173 | 607.193 | 48.6 | 577.137 | 30,056 | 4.9 | 551,569 | 44.1 | 95.6 | 25,568 |

| 29 | Leipzig | 875.282 | 499.025 | 57.0 | 475.065 | 23,960 | 4.8 | 452.574 | 51.7 | 95.3 | 22,491 |

| 30th | Chemnitz-Zwickau | 1,193,690 | 598.265 | 50.1 | 563,822 | 34,443 | 5.8 | 541.011 | 45.3 | 96.0 | 22,811 |

| 31 | Württemberg | 1,657,498 | 591.236 | 35.7 | 582,722 | 8,514 | 1.4 | 563,544 | 34.0 | 96.7 | 19,178 |

| 32 | to bathe | 1,442,138 | 584.472 | 40.5 | 572.163 | 12,309 | 2.1 | 548.417 | 38.0 | 95.8 | 23,746 |

| 33 | Hessen-Darmstadt | 873.472 | 374.728 | 42.9 | 364,572 | 10.156 | 2.7 | 348,954 | 40.0 | 95.7 | 15,618 |

| 34 | Hamburg | 855.998 | 489,695 | 57.2 | 467.233 | 22,462 | 4.6 | 449.142 | 52.5 | 96.1 | 18.091 |

| 35 | Mecklenburg | 574.352 | 212.196 | 36.9 | 202,695 | 9,501 | 4.5 | 195.726 | 34.1 | 96.6 | 6,969 |

| German Empire as a whole | 39,787,013 | 15,599,890 | 39.2 | 15,040,895 | 558.995 | 3.6 | 14,455,181 | 36.3 | 96.1 | 585.714 | |

Constituency cards

literature

Overarching presentations

- Günter Abramowski: Introduction . In: files of the Reich Chancellery . The Marx III and IV cabinets. May 17, 1926 to January 29, 1927, January 29, 1927 to June 29, 1928. Edited by Günter Abramowski. Volume 1: May 1926 to May 1927. Documents No. 1 to 242, Oldenbourg, Munich 1988, pp. XVII-CII. ISBN 3-7646-1861-2 .

- Richard Freyh: Strengths and weaknesses of the Weimar Republic , in: Walter Tormin (Hrsg.): The Weimar Republic . 22nd edition. unchangeable Reprint d. 13th edition. Fackelträger, Hannover 1977, pp. 137-187. ISBN 3-7716-2092-9 .

- Ernst Rudolf Huber : German constitutional history since 1789 . Volume VII: Expansion, Protection and Fall of the Weimar Republic . Kohlhammer / Stuttgart / Berlin / Cologne / Mainz 1984, ISBN 3-17-008378-3 .

- History of the German labor movement . Volume 4. From 1924 to January 1933 . Edited by the Institute for Marxism-Leninism at the Central Committee of the SED. Dietz, Berlin (GDR) 1966.

- Otmar Jung: Direct Democracy in the Weimar Republic. The cases of “revaluation”, “expropriation of princes”, “armored cruiser ban” and “Youngplan” . Campus, Frankfurt / Main / New York 1989. ISBN 3-593-33985-4 .

- Eberhard Kolb : The Weimar Republic . 2., through u. supplementary edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-486-48912-7 .

- Peter Longerich: Germany 1918–1933. The Weimar Republic. Handbuch zur Geschichte , Torchträger, Hannover 1995. ISBN 3-7716-2208-5 .

- Stephan Malinowski: From King to Leader. Social decline and political radicalization in the German nobility between the German Empire and the Nazi state . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-05-003554-4 .

- Hans Mommsen : The playful freedom. The path of the republic from Weimar to its downfall. 1918 to 1933 . Propylaea, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-549-05818-7 .

- Heinrich August Winkler : Workers and the labor movement in the Weimar Republic. The appearance of normality. 1924-1930 . Dietz, Berlin / Bonn 1985, ISBN 3-8012-0094-9 .

- Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. The history of the first German democracy . 2., through Edition. Beck, Munich 1994. ISBN 3-406-37646-0 .

Individual studies on the expropriation of princes

- Kurt Heinig : Hohenzollern. Wilhelm II and his house. The fight for the crown possession. Publishing house for social science, Berlin 1921

- Otmar Jung: People's legislation. The "Weimar experience" from the case of the property dispute between Free States and former princes . Two-volume. 2nd Edition. Kovač, Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-925630-36-8

- Thomas Kluck: Protestantism and Protest in the Weimar Republic. The disputes over the expropriation and appreciation of the princes in the mirror of German Protestantism . With a foreword by Günter Brakelmann. Lang, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin / Bern / New York / Paris / Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-631-50023-8

- Robert Lorenz Civil society between joy and frustration. The call by intellectuals to dispossess the princes in 1926 . In: Johanna Klatt / ders. (Ed.): Manifeste. Past and present of the political appeal . transcript, Bielefeld 2011, pp. 135-167, ISBN 978-3-8376-1679-8

- Ulrich Schüren: The referendum on the expropriation of the princes in 1926. The dispute with the deposed sovereigns as a problem of German domestic politics with special consideration of the conditions in Prussia . Droste, Düsseldorf 1978. ISBN 3-7700-5097-5 .

- Rainer Stentzel: On the relationship between law and politics in the Weimar Republic. The dispute over the so-called expropriation . In: Der Staat , Vol. 39 (2000), Heft 2, pp. 275-297.

Web links

- Expropriation. German Historical Museum Foundation

- Gerhard Immler : Referendum "Expropriation without compensation", 1926 . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria

- Federal Archives

- Save the princes! (PDF; 5.9 MB) Special issue of the satirical magazine Simplicissimus , 1926.

Footnotes

- ↑ Briefly, with evidence, Rainer Stentzel: Relationship , p. 276 and ibid, note 5.

- ^ Constitution of the German Empire of 1919. (PDF; 13 MB) published in the Reichsgesetzblatt

- ↑ See Thomas Kluck: Protestantism , p. 29 and Otmar Jung: Volksgesetzgebung , p. 19 f.

- ↑ Keyword “ Fürstenabfindung ”, in: Fachwortbuch der Geschichte Deutschlands und der deutschen Arbeiterbew Movement, Volume 1, AK , Dietz, Ost-Berlin, 1969, pp. 651–653, here p. 651. In the article “Fürstenabfindung” in the Prussian Lexicon of Prussia .de ( Memento of March 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) is called a total assets of 2.6 billion gold marks, but there are also castles and landed property.

- ↑ Joachim Bergmann: The domestic political development of Thuringia from 1918 to 1932 . Edited by Dietrich Grille and Herbert Hömig. (Ed. On behalf of the Board of Trustees of the Thuringia Foundation (Mainz / Gotha)) Europaforum-Verlag, Lauf ad Pegnitz 2001, ISBN 3-931070-27-1 . There, p. 347: (Document) Letter from the Thuringian Ministry of Finance of January 11, 1925 to the Reich Minister of the Interior regarding the property dispute with the former ruling royal houses.

- ↑ See Rainer Stentzel: Relationship , pp. 278 ff.

- ^ Otmar Jung: People's Legislation , p. 234.

- ↑ On this in detail Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 32 ff and p. 39 ff.

- ↑ Ulrich Schüren: referendum , p. 48 f.

- ↑ Whether such a law would change the constitution was controversial among lawyers, but the majority believed it would. See Ernst Rudolf Huber: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte since 1789, Volume VII , p. 591. Of the constitutional law experts, Carl Schmitt was the one who formulated the thesis that the planned expropriation was not in conformity with the constitution. On this briefly Hans Mommsen: Verspielte Freiheit , p. 248.

- ↑ Figures from Eberhard Kolb: Weimarer Republik , p. 258.

- ↑ On the Kuczynski Committee, see Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 70 ff. And Otmar Jung: Volksgesetzgebung , p. 716 ff.

- ↑ Whether the KPD dominated the committee is controversial. Ulrich Schüren: referendum (p. 74 and more) assumes that Otmar Jung: people's legislation (p. 724–728) contradicts.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Schein der Normalität , p. 273 f.

- ↑ On this Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 87 u. P. 100 ff.

- ↑ a b For exact figures see: Das Deutsche Reich, Plebiscite . gonschior.de

- ↑ On this Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 137 ff. Jung contradicts Schüren when he describes Württemberg as the domain of liberalism. See Otmar Jung: Volksgesetzgebung , p. 814, note 104.

- ↑ Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 141 f. In this context, Jung mentions the cities of Hamburg, Leipzig, Dresden, Hanover, Chemnitz, Stettin and especially Berlin. See Otmar Jung: Volksgesetzgebung , p. 813.

- ^ In addition, Otmar Jung: People's legislation . P. 792 ff.

- ^ In addition, Otmar Jung: People's legislation . P. 800 ff.

- ↑ Gerhard Immler: Referendum “Expropriation without compensation”, 1926 . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria

- ^ From an official DNVP communication, quoted from Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 206.

- ↑ Quoted from Thomas Kluck: Protestantism , p. 54.

- ↑ Quoted from Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 208.

- ↑ Quoted from Thomas Kluck: Protestantism , p. 52.

- ↑ Quoted from Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 210.

- ^ According to his statement on March 9, 1926 in the Donau-Zeitung , quoted in according to Thomas Kluck: Protestantism , p. 48.

- ^ Opinion of May 21, 1926, quoted from Kluck: Protestantism , p. 82.

- ↑ Quoted from Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 212. Quotation also from Thomas Kluck: Protestantismus , p. 107. Kluck works out the history of this statement, p. 100 ff.

- ^ Call of the SPD executive committee, published in: Vorwärts , 43rd year, May 19, 1926, quoted from Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 200.

- ↑ Vorwärts , Volume 43, June 13, 1926, quoted from Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 200.

- ↑ Published in: Die Rote Fahne , 9th year, May 29, 1926, quoted from Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 202.

- ↑ Quoted from Otmar Jung: Volksgesetzgebung , p. 890, note 19.

- ↑ Quoted from Thomas Kluck: Protestantism , p. 45.

- ↑ Not to be confused with the Reich Citizens' Council, which is occasionally mentioned in the literature as the switchboard for opponents of the referendum. See Otmar Jung: Volksgesetzgebung , p. 929.

- ↑ Quoted from Richard Freyh: strengths and weaknesses , p. 147. For the background to the correspondence cf. Otmar Jung: People's Legislation, pp. 927–940.

- ↑ Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 184 and Thomas Kluck: Protestantismus , p. 42.

- ↑ Otmar Jung: Direct Democracy , p. 55 f.

- ↑ Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 185 f.

- ^ On this Hans Mommsen: Verspielte Freiheit , p. 250; Ulrich Schüren: Referendum , p. 154 ff.

- ↑ Quoted from Stephan Malinowski: König , p. 536.

- ↑ Ursula Büttner : Weimar. The overwhelmed republic 1918–1933. Performance and failure in the state, society, economy and culture. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2008, p. 376, ISBN 978-3-608-94308-5 .

- ↑ Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 229 ff and Otmar Jung: Volksgesetzgebung , p. 989 ff.

- ↑ Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 234 ff.

- ↑ Quote from Heinrich August Winkler: Schein der Normalität , p. 283 f.

- ↑ Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 246 f.

- ↑ Günter Abramowski: Introduction , p. XXIV. In Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789, Volume VII , p. 613–615, it is explained why after June 30, 1927 there was no further extension of this suspension of the judicial process .

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Schein der Normalität , p. 287.

- ↑ Details on this: Asset dispute . ( Memento of the original from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Preußenlexikon , Preussen.de

- ↑ Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 258. Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the west. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia 1789–1947 . Aschendorff, Münster 2008, p. 408, ISBN 978-3-402-05489-5 .

- ↑ Peter Longerich: Germany , p. 240, Günter Abramowski: Introduction , p. XXIV.

- ↑ In the appendix by Ulrich Schüren: Referendum , the essential contents of the contract are presented in relation to countries outside of Prussia, see there pp. 284–298. In Otmar Jung: People's legislation see in detail on countries outside of Prussia, pp. 30–431. Jung describes the situation in relation to Prussia on pp. 431-546.

- ↑ On these structural parallels in the severance agreements, see Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 283.

- ↑ On this, Otmar Jung: Volksgesetzgebung , p. 557 f.

- ↑ On this, Otmar Jung: Volksgesetzgebung , p. 561 f.

- ^ History of the German Labor Movement , p. 122.

- ↑ History of the German Labor Movement , p. 115.

- ↑ See also: “The required 20 million votes were not achieved [on June 20, 1926]. The decisive reason for this lay in the behavior of the Social Democratic leaders that prevented a forceful united action of the working class "quote from the article." Prince settlement ", in: Tangible dictionary of the history of Germany and the German labor movement, Volume 1, AK , Dietz, East Berlin, 1969, pp. 651-653, here p. 653.

- ↑ Thomas Kluck: Protestantism . Quote on p. 176.

- ↑ Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 241 and p. 259.

- ↑ Ulrich Schüren: Volksentscheid , p. 279 f.

- ↑ Peter Longerich: Germany , p. 240.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar , p. 314.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Schein der Normalität , p. 289.

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Schein der Normalität , p. 288.

- ↑ Hans Mommsen: Verspielte Freiheit , p. 251. There both quotations.

- ↑ a b Statistisches Reichsamt (Hrsg.): Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich . tape 45 . Published by Reimar Hobbing, Berlin 1926, Chapter XIX. Elections and votes: 4. Referendum and referendum “Expropriation of the Princely Property”, p. 452-453 ( digizeitschriften.de ).